Chapter 4

Taking Charge of Exposure

In This Chapter

Getting a grip on aperture, shutter speed, and ISO

Getting a grip on aperture, shutter speed, and ISO

Exploring advanced exposure modes: P, Tv, Av, and M

Exploring advanced exposure modes: P, Tv, Av, and M

Choosing an exposure metering mode

Choosing an exposure metering mode

Tweaking autoexposure results

Tweaking autoexposure results

Taking advantage of Automatic Exposure Bracketing (AEB)

Taking advantage of Automatic Exposure Bracketing (AEB)

Understanding exposure is one of the most intimidating challenges for a new photographer — and for good reason. Discussions of the topic are loaded with technical terms — aperture, metering, shutter speed, and ISO, to name just a few — and your camera offers many exposure controls, all sporting equally foreign names.

We fully relate to the confusion you may be feeling — we’ve been there. But we can also promise that when you take things nice and slow, digesting a piece of the exposure pie at a time, the topic is not as complicated as it seems on the surface. The payoff will be worth your time, too: You’ll not only gain the know-how to solve just about any exposure problem but also discover ways to use exposure to put your creative stamp on a scene.

To that end, this chapter provides everything you need to know about controlling exposure, from a primer in exposure terminology (it’s not as bad as it sounds) to tips on using the P, Tv, Av, and M exposure modes, which are the only ones that offer access to all exposure features.

Note:

The one exposure-related topic not covered in this chapter is flash; we discuss flash in Chapter 2 because it’s among the options you can access even in Scene Intelligent Auto mode and many of the other point-and-shoot modes. Also, this chapter deals with still photography; see Chapter 8 for information on movie-recording exposure issues.

Introducing the Exposure Trio: Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO

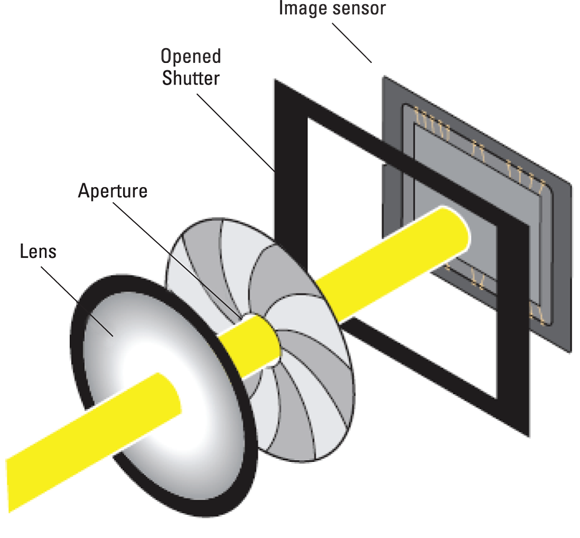

Any photograph, whether taken with a film or digital camera, is created by focusing light through a lens onto a light-sensitive recording medium. In a film camera, the film negative serves as the medium; in a digital camera, it’s the image sensor, which is an array of light-responsive computer chips.

Between the lens and the sensor are two barriers, the aperture and shutter, which together control how much light makes its way to the sensor. The actual design and arrangement of the aperture, shutter, and sensor vary depending on the camera, but Figure 4-1 offers an illustration of the basic concept.

The aperture and shutter, along with a third feature, ISO, determine exposure — what most people would describe as picture brightness. This three-part exposure formula works as follows:

- Aperture (controls amount of light): The aperture is an adjustable hole in a diaphragm set inside the lens. By changing the size of the aperture, you control the size of the light beam that can enter the camera. Aperture settings are stated as f-stop numbers, or simply f-stops, and are expressed with the letter f followed by a number: f/2, f/5.6, f/16, and so on. The lower the f-stop number, the larger the aperture, as illustrated in Figure 4-2. The range of available aperture settings varies from lens to lens.

Shutter speed (controls duration of light): Set behind the aperture, the shutter works something like, er, the shutters on a window. When you aren’t taking pictures, the camera’s shutter stays closed, preventing light from striking the image sensor. When you press the shutter button, the shutter opens briefly to allow light that passes through the aperture to hit the image sensor. The exception to this scenario is when you compose in Live View mode — the shutter remains open so that your image can form on the sensor and be displayed on the camera’s LCD. In fact, when you press the shutter release in Live View mode, you hear several clicks as the shutter first closes and then reopens for the actual exposure.

The length of time that the shutter is open is the shutter speed and is measured in seconds: 1/60 second, 1/250 second, 2 seconds, and so on.

ISO (controls light sensitivity): ISO, which is a digital function rather than a mechanical structure on the camera, enables you to adjust how responsive the image sensor is to light. The term ISO is a holdover from film days, when an international standards organization rated each film stock according to light sensitivity: ISO 100, ISO 200, ISO 400, ISO 800, and so on. A higher ISO rating means greater light sensitivity.

On a digital camera, the sensor doesn’t actually get more or less sensitive when you change the ISO — rather, the light “signal” that hits the sensor is either amplified or dampened through electronics wizardry, sort of like how raising the volume on a radio boosts the audio signal. But the upshot is the same as changing to a more light-reactive film stock: A higher ISO means that less light is needed to produce the image, enabling you to use a smaller aperture, faster shutter speed, or both.

On a digital camera, the sensor doesn’t actually get more or less sensitive when you change the ISO — rather, the light “signal” that hits the sensor is either amplified or dampened through electronics wizardry, sort of like how raising the volume on a radio boosts the audio signal. But the upshot is the same as changing to a more light-reactive film stock: A higher ISO means that less light is needed to produce the image, enabling you to use a smaller aperture, faster shutter speed, or both.

Distilled to its essence, the image-exposure formula is this simple:

Distilled to its essence, the image-exposure formula is this simple:

- Aperture and shutter speed together determine the quantity of light that strikes the image sensor.

- ISO determines how much the sensor reacts to that light.

The tricky part of the equation is that aperture, shutter speed, and ISO settings affect your pictures in ways that go beyond exposure:

- Aperture affects depth of field, or the distance over which focus appears sharp.

- Shutter speed determines whether moving objects appear blurry or sharply focused.

- ISO affects the amount of image noise, which is a defect that looks like tiny specks of sand.

You need to be aware of these side effects, explained in the next sections, to determine which combination of the three exposure settings will work best for your picture. If you’re already familiar with this stuff and just want to know how to adjust exposure settings, skip ahead to the section “Setting ISO, f-stop, and Shutter Speed.”

Aperture affects depth of field

The aperture setting, or f-stop, affects depth of field, or the distance over which sharp focus is maintained. With a shallow depth of field, your subject appears more sharply focused than faraway objects; with a large depth of field, the sharp-focus zone spreads over a greater distance.

When you reduce the aperture size — “stop down the aperture,” in photo lingo — by choosing a higher f-stop number, you increase depth of field. As an example, see Figure 4-3. For both shots, Julie established focus on the fountain statue. Notice that the background in the first image, taken at f/13, is sharper than in the right example, taken at f/5.6. Aperture is just one contributor to depth of field, however; the focal length of the lens and the distance between that lens and your subject also affect how much of the scene stays in focus. See Chapter 5 for the complete story.

One way to remember the relationship between f-stop and depth of field, or the distance over which focus remains sharp, is simply to think of the f as focus: The higher the f-stop number, the larger the zone of sharp focus. (Please don’t share this tip with photography elites, who will roll their eyes and inform you that the f in f-stop most certainly does not stand for focus but, rather, for the ratio between aperture size and lens focal length — as if that’s helpful to know if you aren’t an optical engineer. Chapter 1 explains focal length, which is helpful to know.)

One way to remember the relationship between f-stop and depth of field, or the distance over which focus remains sharp, is simply to think of the f as focus: The higher the f-stop number, the larger the zone of sharp focus. (Please don’t share this tip with photography elites, who will roll their eyes and inform you that the f in f-stop most certainly does not stand for focus but, rather, for the ratio between aperture size and lens focal length — as if that’s helpful to know if you aren’t an optical engineer. Chapter 1 explains focal length, which is helpful to know.)

Shutter speed affects motion blur

At a slow shutter speed, moving objects appear blurry, whereas a fast shutter speed captures motion cleanly. This phenomenon has nothing to do with the actual focus point of the camera but rather on the movement occurring — and being recorded by the camera — while the shutter is open.

Compare the photos in Figure 4-3, for example. The static elements are perfectly focused in both images although the background in the left photo appears sharper because that image was shot using a higher f-stop, increasing the depth of field. But how the camera rendered the moving portion of the scene — the fountain water — was determined by shutter speed. At 1/25 second (left photo), the water blurs, giving it a misty look. At 1/125 second (right photo), the droplets appear more sharply focused, almost frozen in mid-air. How fast a shutter speed you need to freeze action depends on the speed of your subject.

If your picture suffers from overall image blur, like the picture shown in Figure 4-4, where even stationary objects appear out of focus, the camera moved during the exposure — which is always a danger when you handhold the camera at slow shutter speeds. The longer the exposure time, the longer you have to hold the camera still to avoid the blur caused by camera shake.

If your picture suffers from overall image blur, like the picture shown in Figure 4-4, where even stationary objects appear out of focus, the camera moved during the exposure — which is always a danger when you handhold the camera at slow shutter speeds. The longer the exposure time, the longer you have to hold the camera still to avoid the blur caused by camera shake.

Freezing action isn’t the only way to use shutter speed to creative effect. When shooting waterfalls, for example, many photographers use a slow shutter speed to give the water even more of a blurry, romantic look than you see in the fountain example. With colorful subjects, a slow shutter can produce some cool abstract effects and create a heightened sense of motion. Chapter 7 offers examples of both effects.

Freezing action isn’t the only way to use shutter speed to creative effect. When shooting waterfalls, for example, many photographers use a slow shutter speed to give the water even more of a blurry, romantic look than you see in the fountain example. With colorful subjects, a slow shutter can produce some cool abstract effects and create a heightened sense of motion. Chapter 7 offers examples of both effects.

ISO affects image noise

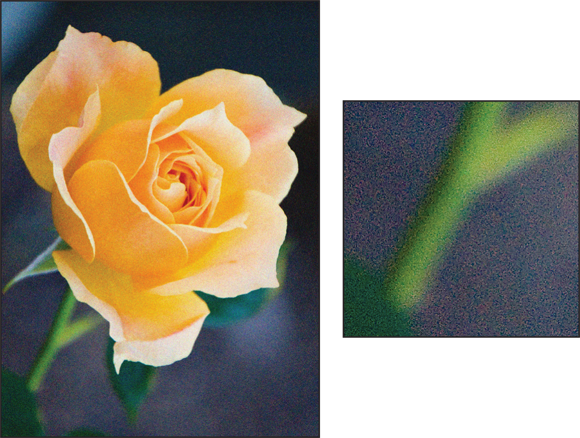

As ISO increases, making the image sensor more reactive to light, you increase the risk of noise. Noise looks like sprinkles of sand and is similar in appearance to film grain, a defect that often mars pictures taken with high ISO film. Figure 4-5 offers an example.

Ideally, then, you should always use the lowest ISO setting on your camera to ensure top image quality. But sometimes the lighting conditions don’t permit you to do so. Take the rose photos in Figure 4-6 as an example. When Julie shot these pictures, she didn’t have a tripod, so she needed a shutter speed fast enough to allow a sharp handheld image. She opened the aperture to f/6.3, which was the widest setting on the lens she was using, to allow as much light as possible into the camera. At ISO 100, the camera needed a shutter speed of 1/40 second to expose the picture, and that shutter speed wasn’t fast enough for a successful handheld shot. You see the blurred result on the left in Figure 4-6. Raising the ISO to 200 allowed a shutter speed of 1/80 second, which was fast enough to capture the flower cleanly, as shown on the right in the figure.

Fortunately, you don’t encounter serious noise on the T6i/750D until you really crank up the ISO. In fact, you may even be able to get away with a fairly high ISO if you keep your print or display size small. Some people probably wouldn’t even notice the noise in the left image in Figure 4-5 unless they were looking for it, for example. But as with other image defects, noise becomes more apparent as you enlarge the photo, as shown on the right in that same figure. Noise is also easier to spot in shadow areas of your picture and in large areas of solid color.

How much noise is acceptable (and, therefore, how high an ISO is safe) is a personal choice. Even a little noise isn’t acceptable for pictures that require the highest quality, such as images for a product catalog or a travel shot that you want to blow up to poster size. To find out about the available noise-reduction options, please flip to the section “Dampening noise,” later in this chapter.

It’s also important to know that a high ISO isn’t the only cause of noise: A long exposure time (slow shutter speed) can also produce the defect. So how high you can raise the ISO before the image gets ugly varies depending on shutter speed. We can pretty much guarantee, though, that your pictures will exhibit visible noise at the camera’s highest normal ISO setting, 12800. (You can bump that up to H, which is equivalent to ISO 25600, by enabling ISO Expansion in Custom Function 2.)

It’s also important to know that a high ISO isn’t the only cause of noise: A long exposure time (slow shutter speed) can also produce the defect. So how high you can raise the ISO before the image gets ugly varies depending on shutter speed. We can pretty much guarantee, though, that your pictures will exhibit visible noise at the camera’s highest normal ISO setting, 12800. (You can bump that up to H, which is equivalent to ISO 25600, by enabling ISO Expansion in Custom Function 2.)

Doing the exposure balancing act

Aperture, shutter speed, and ISO combine to determine image brightness. So changing any one setting means that one or both of the others must also shift to maintain the same image brightness.

Aperture, shutter speed, and ISO combine to determine image brightness. So changing any one setting means that one or both of the others must also shift to maintain the same image brightness.

Suppose that you’re shooting a soccer game and you notice that although the overall exposure looks great, the players appear slightly blurry at the current shutter speed. If you raise the shutter speed, you have to compensate with either a larger aperture, to allow in more light during the shorter exposure, or a higher ISO setting, to make the camera more sensitive to the light. Which way should you go? Well, it depends on whether you prefer the shorter depth of field that comes with a larger aperture or the increased risk of noise that accompanies a higher ISO. Of course, you can also adjust both settings to get the exposure results you need. (We explain how to actually adjust all these settings later.)

All photographers have their own approaches to finding the right combination of aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, and you’ll no doubt develop your own system when you become more practiced at using the advanced exposure modes. In the meantime, here are some handy recommendations:

- Use the lowest possible ISO setting unless the lighting conditions are so poor that you can’t use the aperture and shutter speed you want without raising the ISO.

- If your subject is moving, give shutter speed the next highest priority in your exposure decision. Choose a fast shutter speed to ensure a blur-free photo or, on the flip side, select a slow shutter speed to intentionally blur that moving object, an effect that can create a heightened sense of motion.

- For nonmoving subjects, make aperture a priority over shutter speed, setting the aperture according to the depth of field you have in mind. For portraits, for example, try using a wide-open aperture (a low f-stop number) to create a short depth of field and a nice, soft background for your subject.

Be careful not to go too shallow with depth of field when shooting a group portrait — unless all the subjects are the same distance from the camera, some may be outside the zone of sharp focus. A short depth of field also makes action shots more difficult because you have to be absolutely spot on with focus. With a larger depth of field, the subject can move a greater distance toward or away from you before leaving the sharp-focus area, giving you a bit of a focusing safety net.

Be careful not to go too shallow with depth of field when shooting a group portrait — unless all the subjects are the same distance from the camera, some may be outside the zone of sharp focus. A short depth of field also makes action shots more difficult because you have to be absolutely spot on with focus. With a larger depth of field, the subject can move a greater distance toward or away from you before leaving the sharp-focus area, giving you a bit of a focusing safety net.

Keeping all this information straight is a little overwhelming at first, but the more you work with your camera, the more the whole exposure equation will make sense to you. You can find tips in Chapter 7 for choosing exposure settings for specific types of pictures; keep moving through this chapter for details on how to monitor and adjust aperture, shutter speed, and ISO settings.

Stepping Up to Advanced Exposure Modes (P, Tv, Av, and M)

With your camera in Creative Auto mode, covered in Chapter 3, you can affect picture brightness and depth of field to some extent by using the Shoot by Ambience and Background Blur features. The scene modes let you request a slightly brighter or darker exposure via the Shoot by Ambience setting, but that’s pretty much it. So if you’re really concerned with these picture characteristics — and you should be — set the Mode dial to one of its four advanced exposure modes, highlighted in Figure 4-7: P, Tv, Av, or M.

Chapter 2 introduces the P, Tv, Av, and M modes, but because they’re critical to your control of exposure, we want to offer some additional information here. Using these modes lets you manipulate two critical exposure controls, aperture and shutter speed. That’s not a huge deal in terms of exposure — the camera typically gets that part of the picture right in the fully automatic modes. But changing the aperture setting also affects the distance over which focus is maintained (depth of field), and shutter speed determines whether movement of the subject or camera creates blur. The next part of the chapter explains the details; for now, just understand that having input over these two settings provides you with a whole range of creative options that you don’t enjoy in the fully automatic modes.

Each of the advanced modes offers a different level of control over aperture and shutter speed, as follows:

- P (programmed autoexposure): The camera selects both the aperture and shutter speed to deliver a good exposure at the current ISO setting. But you can choose from different combinations of the two for creative flexibility (which is why this mode is sometimes referred to generically as flexible programmed autoexposure).

Tv (shutter-priority autoexposure): You select a shutter speed, and the camera chooses the aperture setting that produces a good exposure at that shutter speed and the current ISO setting.

Why Tv? Well, shutter speed controls exposure time; Tv stands for time value.

Why Tv? Well, shutter speed controls exposure time; Tv stands for time value.

- Av (aperture-priority autoexposure): The opposite of shutter-priority autoexposure, this mode asks you to select the aperture setting — thus Av, for aperture value. The camera then selects the appropriate shutter speed to properly expose the picture — again, based on the selected ISO setting.

- M (manual exposure): In this mode, you specify both shutter speed and aperture.

To sum up, the first three modes are semiautomatic modes that are designed to offer exposure assistance while still providing you with some creative control. Note one important point about these modes, however: In extreme lighting conditions, the camera may not be able to select settings that will produce a good exposure, and it doesn’t stop you from taking a poorly exposed photo. You may be able to solve the problem by using features designed to modify autoexposure results, such as Exposure Compensation (explained later in this chapter) or by adding flash, but you get no guarantees.

To sum up, the first three modes are semiautomatic modes that are designed to offer exposure assistance while still providing you with some creative control. Note one important point about these modes, however: In extreme lighting conditions, the camera may not be able to select settings that will produce a good exposure, and it doesn’t stop you from taking a poorly exposed photo. You may be able to solve the problem by using features designed to modify autoexposure results, such as Exposure Compensation (explained later in this chapter) or by adding flash, but you get no guarantees.

Manual mode puts all exposure control in your hands. If you’re a longtime photographer who comes from the days when manual exposure was the only game in town, you may prefer to stick with this mode. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, as they say. And in some ways, manual mode is simpler than the semiautomatic modes — if you’re not happy with the exposure, you just change the aperture, shutter speed, or ISO setting and shoot again. You don’t have to fiddle with features that enable you to modify your autoexposure results.

But even when you use the M exposure mode, you’re never really flying without a net: The camera assists you by displaying the exposure meter, explained next.

Monitoring Exposure Settings

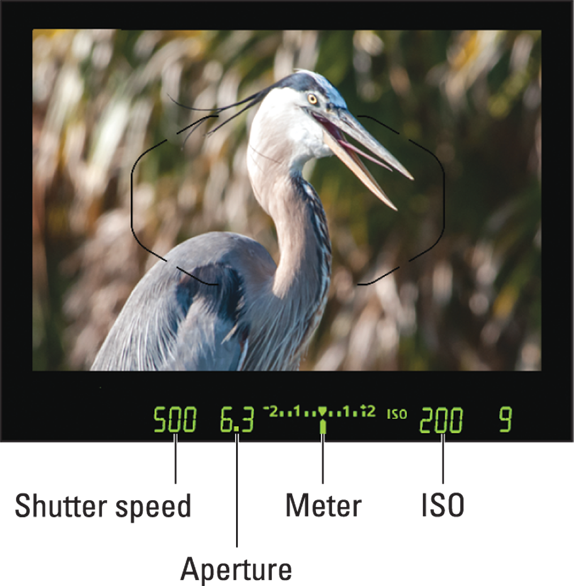

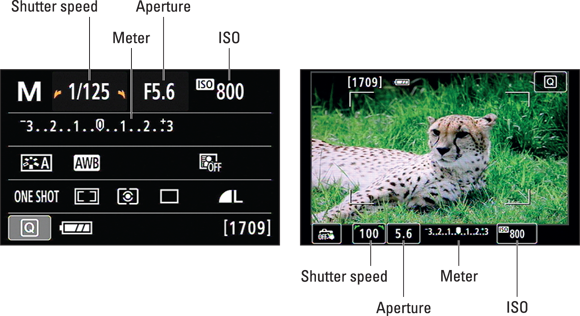

When you press the shutter button halfway, the current f-stop, shutter speed, and ISO speed appear in the viewfinder display, as shown in Figure 4-8. Or if you’re looking at the Shooting Settings or Live View display, the settings appear as shown in Figure 4-9.

In the viewfinder and on the monitor in Live View mode, shutter speeds are presented as whole numbers, even if the shutter speed is set to a fraction of a second. For example, for a shutter speed of 1/60 second, you see just the number 60 in the display. When the shutter speed slows to 1 second or more, you see quotation marks after the number in both displays — 1" indicates a shutter speed of 1 second, 4" means 4 seconds, and so on.

In the viewfinder and on the monitor in Live View mode, shutter speeds are presented as whole numbers, even if the shutter speed is set to a fraction of a second. For example, for a shutter speed of 1/60 second, you see just the number 60 in the display. When the shutter speed slows to 1 second or more, you see quotation marks after the number in both displays — 1" indicates a shutter speed of 1 second, 4" means 4 seconds, and so on.

The viewfinder, Shooting Settings display, and Live View display also offer an exposure meter, labeled in Figures 4-8 and 4-9. This graphic serves two different purposes, depending on the exposure mode:

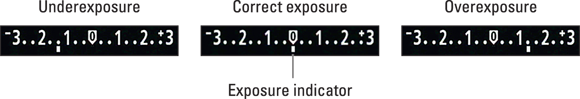

In M mode, the meter acts in its traditional role, which is to indicate whether your settings will properly expose the image. Figure 4-10 gives you three examples. When the exposure indicator (the bar under the meter) aligns with the center point of the meter, as shown in the middle example, the current settings will produce a proper exposure. If the indicator moves to the left of center, toward the minus side of the scale, as in the left example in the figure, the camera is alerting you that the image will be underexposed. If the indicator moves to the right of center, as in the right example, the image will be overexposed. The farther the indicator moves toward the plus or minus sign, the greater the potential exposure problem.

Keep in mind that the information reported by the meter is dependent on the metering mode, which determines what part of the frame the camera uses to calculate exposure. You can choose from three metering modes, as covered in the next section. But regardless of metering mode, consider the meter a guide, not a dictator — the beauty of manual exposure is that you decide how dark or bright an exposure you want, not the camera.

Keep in mind that the information reported by the meter is dependent on the metering mode, which determines what part of the frame the camera uses to calculate exposure. You can choose from three metering modes, as covered in the next section. But regardless of metering mode, consider the meter a guide, not a dictator — the beauty of manual exposure is that you decide how dark or bright an exposure you want, not the camera.

In the other modes (P, Tv, and Av), the meter displays the current Exposure Compensation setting. Remember, in those modes the camera sets either the shutter speed or aperture, or both, to produce a good exposure — again, depending on the current metering mode. Because you don’t need the meter to tell you whether exposure is okay, the meter instead indicates whether you enabled Exposure Compensation, a feature that forces a brighter or darker exposure than the camera thinks is appropriate. (Look for details later in this chapter.) When the exposure indicator is at 0, no compensation is being applied. If the indicator is to the right of 0, you applied compensation to produce a brighter image; when the indicator is to the left, you asked for a darker photo.

In some lighting situations, the camera can’t select settings that produce an optimal exposure in the P, Tv, or Av modes, however. Because the meter indicates the exposure compensation amount in those modes, the camera alerts you to exposure issues as follows:

In some lighting situations, the camera can’t select settings that produce an optimal exposure in the P, Tv, or Av modes, however. Because the meter indicates the exposure compensation amount in those modes, the camera alerts you to exposure issues as follows:

- Av mode (aperture-priority autoexposure): The shutter speed value blinks to let you know that the camera can’t select a shutter speed that will produce a good exposure at the aperture you selected. Choose a different f-stop or adjust the ISO.

- Tv mode (shutter-priority autoexposure): The aperture value blinks to tell you that the camera can’t open or stop down the aperture enough to expose the image at your selected shutter speed. Your options are to change the shutter speed or ISO.

- P mode (programmed autoexposure): In P mode, both the aperture and shutter speed values blink if the camera can’t select a combination that will properly expose the image. Your only recourse is to either adjust the lighting or change the ISO setting.

Choosing an Exposure Metering Mode

The metering mode determines which part of the frame the camera analyzes to calculate the proper exposure. Your camera offers four metering modes, described in the following list and represented in the Shooting Settings by the icons you see in the margin.

You can access all four metering modes only in the advanced exposure modes (P, Tv, Av, and M). They are available during regular, through-the-viewfinder shooting as well as in Live View mode. In the fully automatic exposure modes, the camera always uses Evaluative metering.

You can access all four metering modes only in the advanced exposure modes (P, Tv, Av, and M). They are available during regular, through-the-viewfinder shooting as well as in Live View mode. In the fully automatic exposure modes, the camera always uses Evaluative metering.

Evaluative metering: The camera analyzes the entire frame and then selects exposure settings designed to produce a balanced exposure.

Evaluative metering: The camera analyzes the entire frame and then selects exposure settings designed to produce a balanced exposure.

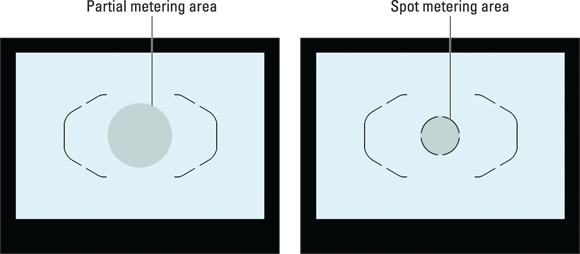

Partial metering: The camera bases exposure only on the light that falls in the center 6 percent of the frame. The left image in Figure 4-11 provides a rough approximation of the area that factors into the exposure equation.

Partial metering: The camera bases exposure only on the light that falls in the center 6 percent of the frame. The left image in Figure 4-11 provides a rough approximation of the area that factors into the exposure equation.

Spot metering: This mode works like Partial metering but uses a smaller region of the frame to calculate exposure. For Spot metering, exposure is based on just the central 3.5 percent of the frame, as indicated by the illustration on the right in Figure 4-11.

Spot metering: This mode works like Partial metering but uses a smaller region of the frame to calculate exposure. For Spot metering, exposure is based on just the central 3.5 percent of the frame, as indicated by the illustration on the right in Figure 4-11.

Center-Weighted Average metering: The camera bases exposure on the entire frame but puts extra emphasis — or weight — on the center.

Center-Weighted Average metering: The camera bases exposure on the entire frame but puts extra emphasis — or weight — on the center.

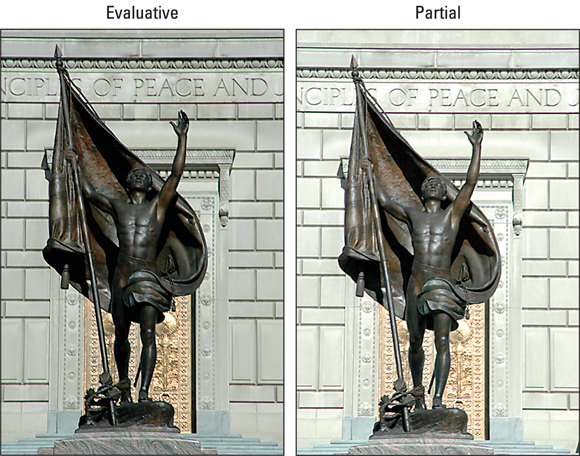

In most cases, Evaluative metering does a good job of calculating exposure. But it can get thrown off when a dark subject is set against a bright background, or vice versa. For example, in the left image in Figure 4-12, the amount of bright background caused the camera to select exposure settings that underexposed the statue, which was the point of interest for the photo. Switching to Partial metering properly exposed the statue. (Spot metering would produce a similar result for this particular subject.)

Of course, if the background is very bright and the subject is very dark, the exposure that does the best job on the subject typically overexposes the background. You may be able to reclaim some lost highlights by turning on Highlight Tone Priority, a Custom Function explored later in this chapter.

Of course, if the background is very bright and the subject is very dark, the exposure that does the best job on the subject typically overexposes the background. You may be able to reclaim some lost highlights by turning on Highlight Tone Priority, a Custom Function explored later in this chapter.

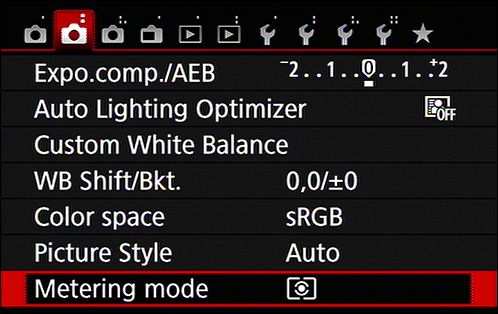

Use either of these two options to change the metering mode:

Quick Control screen: Choose the icon labeled in Figure 4-13 and rotate the Main dial to cycle through the four modes. Or tap the icon or press the Set button to display all four modes on one selection screen, as shown on the right in the figure. If you choose the second route, choose the icon representing the mode you want to use and then press Set or tap the return arrow to lock in your decision.

Quick Control screen: Choose the icon labeled in Figure 4-13 and rotate the Main dial to cycle through the four modes. Or tap the icon or press the Set button to display all four modes on one selection screen, as shown on the right in the figure. If you choose the second route, choose the icon representing the mode you want to use and then press Set or tap the return arrow to lock in your decision.- Shooting Menu 2: You also can find the Metering Mode option at the menu address shown in Figure 4-14.

In theory, the best practice is to check the Metering mode before each shot and choose the mode that best matches your exposure goals (when in Live View, the monitor shows you the anticipated results of the current exposure settings). But in practice, it’s a pain, not just in terms of having to adjust yet one more setting but also in terms of having to remember to adjust one more setting. So until you’re comfortable with all the other controls on your camera, just stick with Evaluative metering. It produces good results in most situations, and after all, you can see in the monitor whether you like your results and, if not, adjust exposure settings and reshoot. This option makes the whole Metering mode issue a lot less critical than it is when you shoot with film.

In theory, the best practice is to check the Metering mode before each shot and choose the mode that best matches your exposure goals (when in Live View, the monitor shows you the anticipated results of the current exposure settings). But in practice, it’s a pain, not just in terms of having to adjust yet one more setting but also in terms of having to remember to adjust one more setting. So until you’re comfortable with all the other controls on your camera, just stick with Evaluative metering. It produces good results in most situations, and after all, you can see in the monitor whether you like your results and, if not, adjust exposure settings and reshoot. This option makes the whole Metering mode issue a lot less critical than it is when you shoot with film.

The one exception might be when you’re shooting a series of images in which a significant contrast in lighting exists between subject and background. Then, switching to Center-Weighted metering or Partial metering may save you the time spent having to adjust the exposure for each image. Many portrait photographers, for example, rely on Center-Weighted or Partial metering exclusively because they know their subject is usually going to be hovering near the center of the frame. Use Spot metering when you need more precision than Center-Weighted or Partial metering can provide. Sometimes, you’ll need to get a very accurate reading of a specific element in the photo to keep it from being over- or underexposed.

Setting ISO, f-stop, and Shutter Speed

If you want to control ISO, aperture (f-stop), or shutter speed, set the camera to one of the advanced exposure modes: P, Tv, Av, or M. Then check out the next several sections to find the exact steps to follow in each of these modes.

If you want to control ISO, aperture (f-stop), or shutter speed, set the camera to one of the advanced exposure modes: P, Tv, Av, or M. Then check out the next several sections to find the exact steps to follow in each of these modes.

Controlling ISO

To recap the ISO information presented at the start of this chapter, your camera’s ISO setting controls how sensitive the image sensor is to light. At a camera’s higher ISO values, you need less light to expose an image correctly. Remember the downside to raising ISO, however: The higher the ISO, the greater the possibility of noisy images. Refer to Figure 4-5 for a reminder of what that defect looks like.

In Scene Intelligent Auto, Creative Auto, Flash Off, and the scene modes (Portrait, Landscape, and so on), the camera controls ISO. But in the advanced exposure modes, you have the following ISO choices:

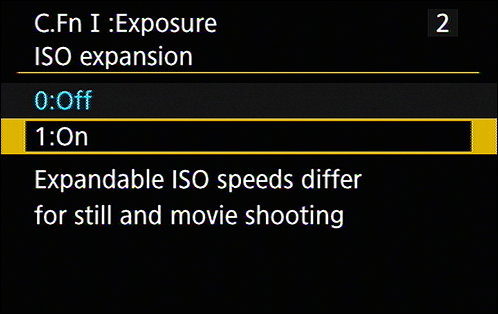

Select a specific ISO setting. Normally, you can choose ISO settings ranging from 100 to ISO 12800. Or if you really want to push things, you can amp ISO up to 25600. In order to take advantage of that option, set Custom Function 2, ISO Expansion, to On, as shown in Figure 4-15. Now when you adjust ISO, an H (for High) appears as a possible setting; select that setting for ISO 25600.

A few complications to note: If you enable Highlight Tone Priority, an exposure feature covered later in this chapter, you lose the option of using ISO 100 as well as the expanded ISO setting (H, 25600). In addition, choosing H (ISO 25600) slows the maximum burst rate the camera can achieve in Continuous Drive mode.

A few complications to note: If you enable Highlight Tone Priority, an exposure feature covered later in this chapter, you lose the option of using ISO 100 as well as the expanded ISO setting (H, 25600). In addition, choosing H (ISO 25600) slows the maximum burst rate the camera can achieve in Continuous Drive mode.

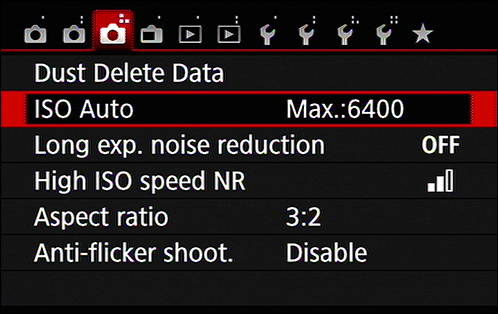

Let the camera choose (Auto ISO). You can ask the camera to adjust ISO for you if you prefer. And you can specify the highest ISO setting that you want the camera to use, which you can limit to as little as ISO 400 or as much as ISO 6400. Set the top ISO limit via the ISO Auto setting on Shooting Menu 3, as shown in Figure 4-16, which shows the default maximum of ISO 6400.

Using Auto ISO is especially handy when the light is changing fast or your subject is moving from light to dark areas quickly. In these situations, Auto ISO can save the day, giving you properly exposed images without any ISO futzing on your part.

Using Auto ISO is especially handy when the light is changing fast or your subject is moving from light to dark areas quickly. In these situations, Auto ISO can save the day, giving you properly exposed images without any ISO futzing on your part.

You can view the current ISO setting in Shooting Settings and Live View displays, as shown in Figure 4-17, as well as in the viewfinder, as shown in Figure 4-18. (If you don’t see the value in Live View mode, press the Info button to switch to a display mode that presents the data.)

In Auto ISO mode, the Shooting Settings and Live View displays initially show Auto as the ISO value, as you would expect. But when you press the shutter button halfway, which initiates exposure metering, the value changes to show you the ISO setting the camera has selected. You also see the selected value rather than Auto in the viewfinder.

In Auto ISO mode, the Shooting Settings and Live View displays initially show Auto as the ISO value, as you would expect. But when you press the shutter button halfway, which initiates exposure metering, the value changes to show you the ISO setting the camera has selected. You also see the selected value rather than Auto in the viewfinder.

Note:

When you view shooting data during playback, you may see a value reported that isn’t on the list of “official” ISO settings — ISO 320, for example. This happens because in Auto mode, the camera can select values all along the available ISO range, whereas if you select a specific ISO setting, you’re restricted to specific notches within the range.

To adjust the ISO setting, you have these options:

Press the ISO button (on top of the camera, as shown in Figure 4-19). You then see the screen shown on the right in Figure 4-20, where you can choose your desired setting.

Use the Quick Control screen. After choosing the ISO option, as shown on the left in Figure 4-20, rotate the Main dial to cycle through the available ISO settings. You also can tap the icon or press Set to display a screen containing all the available options, as shown on the right in the figure and select your choice there.

Use the Quick Control screen. After choosing the ISO option, as shown on the left in Figure 4-20, rotate the Main dial to cycle through the available ISO settings. You also can tap the icon or press Set to display a screen containing all the available options, as shown on the right in the figure and select your choice there.

Figure 4-20 shows you how the screens appear during viewfinder shooting. In Live View mode, ISO does not appear as part of the Quick Control screen. You should use the ISO button in that case. You can read about noise reduction in the upcoming “Dampening noise” section.

Adjusting aperture and shutter speed

You can adjust aperture and shutter speed only in P, Tv, Av, and M exposure modes. To wake up the exposure meter and view the current f-stop and shutter speed in the displays, press the shutter button halfway.

You can adjust aperture and shutter speed only in P, Tv, Av, and M exposure modes. To wake up the exposure meter and view the current f-stop and shutter speed in the displays, press the shutter button halfway.

The following actions then take place:

- The exposure meter comes to life. If autofocus is enabled, focus is also established at this point.

- The aperture and shutter speed appear in the viewfinder or the Shooting Settings display, if you have it enabled. In Live View mode, the settings appear at the bottom of the screen, assuming that you’re using a display mode that reveals shooting data. (Press the Info button to cycle through the available Live View display modes.)

- In manual exposure (M) mode, the exposure meter lets you know whether the current settings will expose the image properly. In the other modes, the camera indicates an exposure problem by flashing the shutter speed or the f-stop value. (See the section “Monitoring Exposure Settings,” earlier in this chapter, for details.)

Then use these techniques to adjust the settings, depending on your exposure mode:

- P (programmed auto): The camera displays its recommended combination of aperture and shutter speed. To select a different combination, rotate the Main dial.

Tv (shutter-priority autoexposure): Rotate the Main dial to set the shutter speed. The camera automatically adjusts the aperture as needed to maintain the proper exposure at the chosen shutter speed.

As you change shutter speeds, the camera adjusts the f-stop in conjunction with the ISO to reach the ideal exposure. Keep an eye on the f-stop if depth of field is important to your photo. Note:

In extreme lighting conditions, the camera may not be able to adjust the aperture enough to produce a good exposure at the current shutter speed — again, possible aperture settings depend on your lens. So you may need to compromise on shutter speed (or, in dim lighting, raise the ISO).

As you change shutter speeds, the camera adjusts the f-stop in conjunction with the ISO to reach the ideal exposure. Keep an eye on the f-stop if depth of field is important to your photo. Note:

In extreme lighting conditions, the camera may not be able to adjust the aperture enough to produce a good exposure at the current shutter speed — again, possible aperture settings depend on your lens. So you may need to compromise on shutter speed (or, in dim lighting, raise the ISO).

Av (aperture-priority autoexposure): Rotate the Main dial to change the f-stop setting. As you do, the camera adjusts the shutter speed to produce the proper exposure.

After changing the aperture, make sure that the shutter speed hasn’t dropped so low that handholding the camera or capturing a moving subject won’t be possible. If this problem arises, use a higher ISO setting, which will enable the camera to select a faster shutter speed.

After changing the aperture, make sure that the shutter speed hasn’t dropped so low that handholding the camera or capturing a moving subject won’t be possible. If this problem arises, use a higher ISO setting, which will enable the camera to select a faster shutter speed.

- M (manual exposure): Select aperture and shutter speed like so:

- Note:

If you’re using the kit lens (or indeed, any other lens with IS), turn off Image Stabilization (IS) when you set the shutter speed to Bulb in Manual exposure mode.

In M, Tv, and Av modes, the setting that’s available for adjustment appears in the Shooting Settings display with little arrows at each side. Your camera manual refers to this display as the Main dial pointer, and it’s provided as a reminder that you use the Main dial to change the setting. For example, in M mode, the shutter speed is bordered by the arrows until you hold down the Exposure Compensation button, at which point the marker shifts to the aperture (f-stop) value, as shown in Figure 4-21.

In M, Tv, and Av modes, the setting that’s available for adjustment appears in the Shooting Settings display with little arrows at each side. Your camera manual refers to this display as the Main dial pointer, and it’s provided as a reminder that you use the Main dial to change the setting. For example, in M mode, the shutter speed is bordered by the arrows until you hold down the Exposure Compensation button, at which point the marker shifts to the aperture (f-stop) value, as shown in Figure 4-21.

When the Shooting Settings screen is displayed, you also can use the Quick Control screen to adjust the settings in the M, Tv, and Av modes. This technique is more cumbersome but comes in handy in M mode because you can adjust the f-stop setting without having to remember what button to push to do the job. The Quick Control method doesn’t work in Live View mode.

When the Shooting Settings screen is displayed, you also can use the Quick Control screen to adjust the settings in the M, Tv, and Av modes. This technique is more cumbersome but comes in handy in M mode because you can adjust the f-stop setting without having to remember what button to push to do the job. The Quick Control method doesn’t work in Live View mode.

A few more words of wisdom related to aperture and shutter speed:

- When using Manual exposure, don’t forget that you can check the exposure meter to get the camera’s take on your exposure settings (when in Live View, look at the monitor for a preview). Of course, you don’t have to follow the camera’s guidance — you can take the picture using any settings you like, even if the meter indicates that the image will be under- or overexposed.

In P, Tv, and Av mode, the shutter speed or f-stop value blinks if the camera isn’t able to select settings that produce a good exposure. If the problem is too little light, try raising the ISO or adding flash to solve the problem. If there’s too much light, lower the ISO value or attach an ND (neutral density) filter, which is sort of like sunglasses for your lens — it simply cuts the light entering the lens. (The neutral part just means that the filter doesn’t affect image colors, just brightness.)

In P, Tv, and Av mode, the shutter speed or f-stop value blinks if the camera isn’t able to select settings that produce a good exposure. If the problem is too little light, try raising the ISO or adding flash to solve the problem. If there’s too much light, lower the ISO value or attach an ND (neutral density) filter, which is sort of like sunglasses for your lens — it simply cuts the light entering the lens. (The neutral part just means that the filter doesn’t affect image colors, just brightness.)

- Keep in mind that when you use P, Tv, and Av modes, the settings that the camera selects are based on what it thinks is the proper exposure. If you don’t agree with the camera, you have two options. Switch to manual exposure (M) mode and simply dial in the aperture and shutter speed that deliver the exposure you want, or if you want to stay in P, Tv, or Av mode, try using exposure compensation, one of the exposure-correction tools described in the next section.

Sorting Through Your Camera’s Exposure-Correction Tools

In addition to the normal controls over aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, your Rebel offers a collection of tools that enable you to solve tricky exposure problems. The next four sections give you the lowdown on these features.

Overriding autoexposure results with Exposure Compensation

In the P, Tv, and Av exposure modes, you have some input over exposure: In P mode, you can rotate the Main dial to choose from different combinations of aperture and shutter speed; in Tv mode, you can dial in the shutter speed; and in Av mode, you can select the aperture setting. But because these are semiautomatic modes, the camera ultimately controls the final exposure. If your picture turns out too bright or too dark in P mode, you can’t simply choose a different f-stop/shutter speed combo because they all deliver the same exposure — which is to say, the exposure that the camera has in mind. And changing the shutter speed in Tv mode or adjusting the f-stop in Av mode won’t help either because as soon as you change the setting that you’re controlling, the camera automatically adjusts the other setting to produce the same exposure it initially delivered.

In the P, Tv, and Av exposure modes, you have some input over exposure: In P mode, you can rotate the Main dial to choose from different combinations of aperture and shutter speed; in Tv mode, you can dial in the shutter speed; and in Av mode, you can select the aperture setting. But because these are semiautomatic modes, the camera ultimately controls the final exposure. If your picture turns out too bright or too dark in P mode, you can’t simply choose a different f-stop/shutter speed combo because they all deliver the same exposure — which is to say, the exposure that the camera has in mind. And changing the shutter speed in Tv mode or adjusting the f-stop in Av mode won’t help either because as soon as you change the setting that you’re controlling, the camera automatically adjusts the other setting to produce the same exposure it initially delivered.

Not to worry: You actually do have final say over exposure in these exposure modes. The secret is Exposure Compensation, a feature that tells the camera to produce a brighter or darker exposure on your next shot, whether or not you change the aperture or shutter speed (or both, in P mode).

Best of all, this feature is probably one of the easiest on the camera to understand. Here’s all there is to it:

- Exposure compensation is stated in EV values, as in +2.0 EV. Possible values range from +5.0 EV to –5.0 EV.

Each full number on the EV scale represents an exposure shift of one full stop. In plain English, it means that if you change the Exposure Compensation setting from EV 0.0 to EV –1.0, the camera adjusts either the aperture or the shutter speed to allow half as much light into the camera as it would get at the current setting. If you instead raise the value to EV +1.0, the settings are adjusted to double the light.

Each full number on the EV scale represents an exposure shift of one full stop. In plain English, it means that if you change the Exposure Compensation setting from EV 0.0 to EV –1.0, the camera adjusts either the aperture or the shutter speed to allow half as much light into the camera as it would get at the current setting. If you instead raise the value to EV +1.0, the settings are adjusted to double the light.

- A setting of EV 0.0 results in no exposure adjustment.

- For a brighter image, you raise the EV value. The higher you go, the brighter the image becomes.

- For a darker image, you lower the EV value. The picture becomes progressively darker with each step down the EV scale.

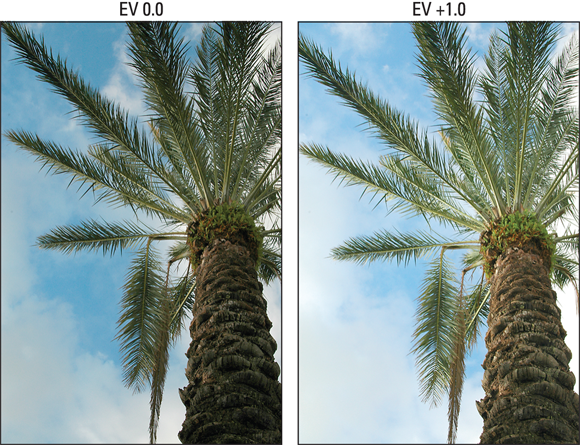

Exposure compensation is especially helpful when your subject is much lighter or darker than an average scene. For example, take a look at the image on the left in Figure 4-22. Because of the very bright sky, the camera chose an exposure that made the tree too dark. Setting the Exposure Compensation value to EV +1.0 resulted in a properly exposed image.

Exposure compensation is especially helpful when your subject is much lighter or darker than an average scene. For example, take a look at the image on the left in Figure 4-22. Because of the very bright sky, the camera chose an exposure that made the tree too dark. Setting the Exposure Compensation value to EV +1.0 resulted in a properly exposed image.

Sometimes you can cope with situations like this one by changing the Metering mode, as discussed earlier in this chapter. The images in Figure 4-22 were metered in Evaluative mode, for example, which meters exposure over the entire frame. Switching to Partial or Spot metering probably wouldn’t have helped in this case because the center of the frame was bright. In any case, it’s usually easier to simply adjust exposure compensation than to experiment with metering modes.

You can take several roads to applying exposure compensation:

You can take several roads to applying exposure compensation:

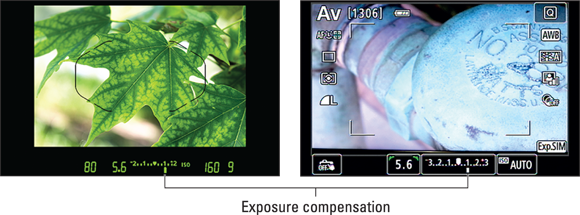

Exposure Compensation button: The fastest option is to press and hold the Exposure Compensation button while rotating the Main dial. As you adjust the setting, the exposure meter in the Viewfinder and Live View displays indicates the current Exposure Compensation amount. For example, in Figure 4-23, the amount of adjustment is +1.0. The Shooting Settings screen also displays the amount of adjustment.

Exposure Compensation button: The fastest option is to press and hold the Exposure Compensation button while rotating the Main dial. As you adjust the setting, the exposure meter in the Viewfinder and Live View displays indicates the current Exposure Compensation amount. For example, in Figure 4-23, the amount of adjustment is +1.0. The Shooting Settings screen also displays the amount of adjustment.

Note that even though the meters initially show a range of just +/– three stops (two in the case of the viewfinder), you can access the entire five-stop range. Just keep rotating the Main dial to display the far ends of the range.

Quick Control screen (not available in Live View mode): Highlight the exposure meter in the Quick Control display and rotate the Main dial to move the exposure indicator left or right along the meter, as shown on the left in Figure 4-24. When you exit the Quick Control screen, the Shooting Settings display appears as shown on the right in Figure 4-24.

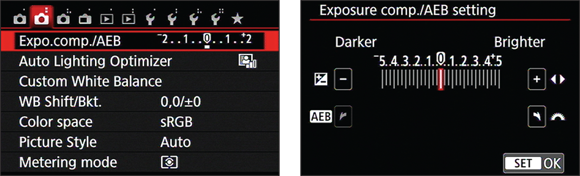

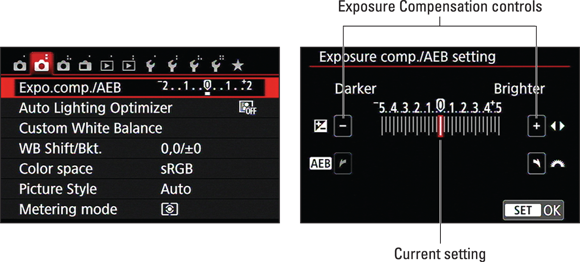

Quick Control screen (not available in Live View mode): Highlight the exposure meter in the Quick Control display and rotate the Main dial to move the exposure indicator left or right along the meter, as shown on the left in Figure 4-24. When you exit the Quick Control screen, the Shooting Settings display appears as shown on the right in Figure 4-24.Shooting Menu 2: Select Expo Comp/AEB, as shown on the left in Figure 4-25, and press Set to display the screen shown on the right in the figure. You can access this same screen by pressing set when the meter is highlighted on the Quick Control screen.

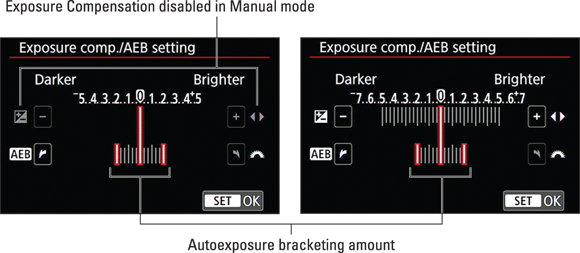

Either way, this is a tricky screen, so pay attention:

- The screen has a double purpose: You use it to enable automatic exposure bracketing (AEB) as well as exposure compensation. So if you’re not careful, you can wind up changing the wrong setting.

- To apply exposure compensation, move the exposure indicator (labeled current setting in the figure) along the scale by pressing the left or right cross keys or tapping the plus or minus signs, labeled Exposure Compensation controls in the figure. If you rotate the Main dial, you adjust the AEB setting instead.

- Tap Set or press the Set button to lock in the amount of exposure compensation and exit the screen.

When you dial in an adjustment of greater than three stops, the notch under the viewfinder meter disappears and is replaced by a little triangle at one end of the meter — at the right end for a positive Exposure Compensation value and at the left for a negative value. However, the meter on the Shooting Settings and Live View screens and on Shooting Menu 2 adjust to show the proper setting.

When you dial in an adjustment of greater than three stops, the notch under the viewfinder meter disappears and is replaced by a little triangle at one end of the meter — at the right end for a positive Exposure Compensation value and at the left for a negative value. However, the meter on the Shooting Settings and Live View screens and on Shooting Menu 2 adjust to show the proper setting.

Whatever setting you select, the way that the camera arrives at the brighter or darker image you request depends on the exposure mode:

- In Av (aperture-priority) mode, the camera adjusts the shutter speed but leaves your selected f-stop in force.

- In Tv (shutter-priority) mode, the opposite occurs: The camera opens or stops down the aperture, leaving your selected shutter speed alone.

- In P (programmed autoexposure) mode, the camera decides whether to adjust aperture, shutter speed, or both to accommodate the Exposure Compensation setting.

These explanations assume that you have a specific ISO setting selected rather than Auto ISO. If you do use Auto ISO, the camera may adjust that value instead.

Keep in mind, too, that the camera can adjust the aperture only so much, according to the aperture range of your lens. The range of shutter speeds is limited by the camera. So if you reach the end of those ranges, you have to compromise on either shutter speed or aperture, or adjust ISO.

A final, and critical, point about exposure compensation: When you power off the camera, it doesn’t return you to a neutral setting (EV 0.0). The setting you last used remains in force for the P, Tv, and Av modes until you change it. So it’s always a good idea to zero out the setting at the end of a shoot.

A final, and critical, point about exposure compensation: When you power off the camera, it doesn’t return you to a neutral setting (EV 0.0). The setting you last used remains in force for the P, Tv, and Av modes until you change it. So it’s always a good idea to zero out the setting at the end of a shoot.

Improving high-contrast shots with Highlight Tone Priority

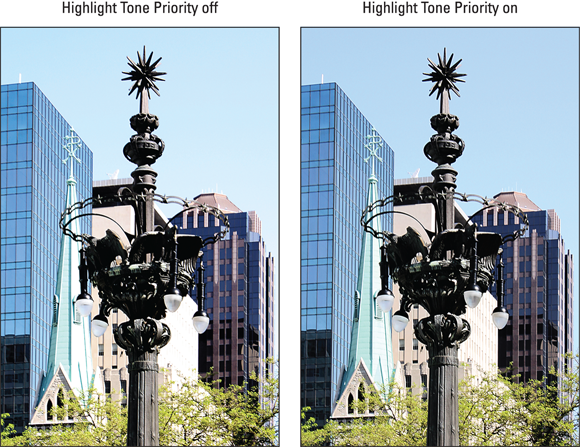

When a scene contains both very dark and very bright areas, achieving a good exposure can be difficult. If you choose exposure settings that render the shadows properly, the highlights are often overexposed, as in the left image in Figure 4-26. Although the dark lamppost in the foreground looks fine, the white building behind it has become so bright that all detail has been lost. The same thing occurred in the highlight areas of the green church steeple.

Your camera offers an option that can help produce a better image in this situation — Highlight Tone Priority — which was used to produce the image on the right in Figure 4-26. The difference is subtle, but if you look at that white building and steeple, you can see that the effect does make a difference. Now the windows in the building are at least visible, the steeple has regained some of its color, and the sky, too, has a bit more blue.

This feature is available only in the P, Tv, Av, and M modes. It’s turned off by default, which may seem like an odd choice after looking at the improvement it made to the scene in Figure 4-26. What gives? The answer is that in order to do its thing, Highlight Tone Priority needs to play with a few other camera settings, as follows:

This feature is available only in the P, Tv, Av, and M modes. It’s turned off by default, which may seem like an odd choice after looking at the improvement it made to the scene in Figure 4-26. What gives? The answer is that in order to do its thing, Highlight Tone Priority needs to play with a few other camera settings, as follows:

- The ISO range is reduced to ISO 200–12800. The camera needs the more limited range in order to favor the image highlights.

- Auto Lighting Optimizer is disabled. This feature, which attempts to improve image contrast, is incompatible with Highlight Tone Priority. So read the next section, which explains Auto Lighting Optimizer, to determine which of the two exposure tweaks you want to use.

- You can wind up with slightly more noise in shadow areas of the image. Again, noise is the defect that looks like speckles in your image.

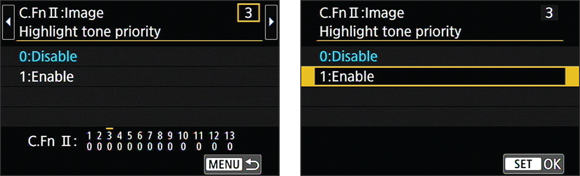

The only way to enable Highlight Tone Priority is via Custom Function 3, found on Setup Menu 4 and shown in Figure 4-27.

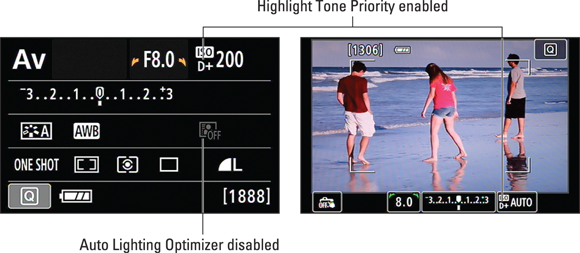

As a reminder that Highlight Tone Priority is enabled, a D+ symbol appears near the ISO value in the Shooting Settings and Live View displays, as shown in Figure 4-28. The same symbol appears with the ISO setting in the viewfinder and in the shooting data that appears in Playback mode. (See Chapter 9 to find out more about picture playback.) Notice that the symbol that represents Auto Lighting Optimizer is dimmed because that feature is now disabled.

Experimenting with Auto Lighting Optimizer

When you select an Image Quality setting that results in a JPEG image file — that is, any setting other than Raw — the camera tries to enhance your photo while it’s processing the picture. Unlike Highlight Tone Priority, which concentrates on preserving highlight detail only, Auto Lighting Optimizer adjusts both shadows and highlights to improve the final image tonality (range of darks to lights). In other words, it’s a contrast adjustment.

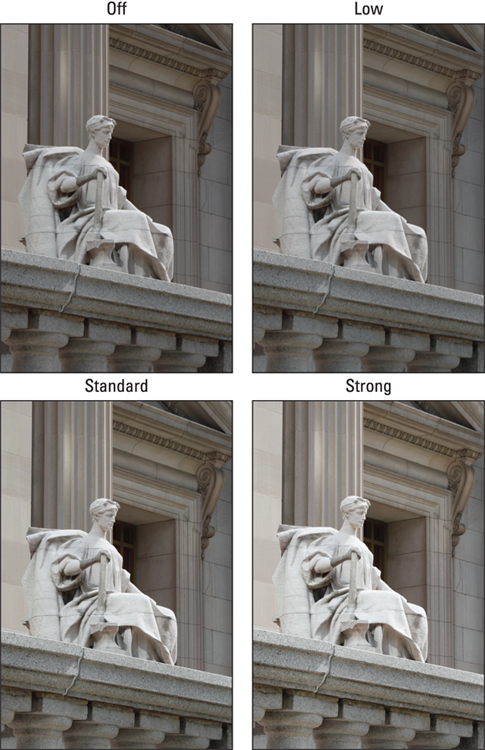

In the fully automatic exposure modes as well as in Creative Auto, you have no control over how much adjustment is made. But in P, Tv, Av, and M modes, you can decide whether to enable Auto Lighting Optimizer. You also can request a stronger or lighter application of the effect than the default setting. Figure 4-29 offers an example of the type of impact of each Auto Lighting Optimizer setting.

Given the level of improvement that the Auto Lighting Optimizer correction made to this photo, you may be thinking that you’d be crazy to ever disable the feature. But it’s important to note a few points:

In the Shooting Settings and Live View displays, look for the icon representing this setting in the areas labeled in Figure 4-30. Notice the little vertical bars in the graphic — the number of bars tells you how much adjustment is being applied. Two bars, as in Figure 4-30, represent the Standard setting, which is the default; three bars, Strong; and one bar, Low. The bars are replaced by the word Off when the feature is disabled.

You can adjust the setting in two ways:

Quick Control screen: Choose the option, labeled in Figure 4-30, and rotate the Main dial to adjust the level of adjustment. To access the option that enables you to turn the shift on and off for Manual exposure mode, tap the Auto Lighting Optimizer icon or highlight it and press Set; you then see the second screen in the Figure 4-31. Tap the check box or press the Info button to toggle the adjustment on and off for Manual exposure mode. Exit the screen by tapping the Return arrow or pressing Set.

Notice the little vertical bars that appear as part of the setting icon — the number of bars tells you how much adjustment is being applied. Two bars, as in Figure 4-30, represent the Standard setting; three bars, High, and one bar, Low. The bars are replaced by the word Off when the feature is disabled.

Notice the little vertical bars that appear as part of the setting icon — the number of bars tells you how much adjustment is being applied. Two bars, as in Figure 4-30, represent the Standard setting; three bars, High, and one bar, Low. The bars are replaced by the word Off when the feature is disabled.

- Shooting Menu 2: Select the option and press Set to display the selection screen, as shown on the left in Figure 4-31. (Remember: This menu option appears only when the Mode dial is set to P, Tv, Av, or M.)

If you’re not sure what level of Auto Lighting Optimizer might work best or you’re concerned about the other drawbacks of enabling the filter, consider shooting the picture in the Raw file format. For Raw pictures, the camera applies no post-capture tweaking, regardless of whether this filter or any other one is enabled. Then, by using Canon Digital Photo Professional, the software provided free with the camera, you can apply the Auto Lighting Optimizer effect when you convert your Raw images to a standard file format. (See Chapter 10 for details about processing Raw files.)

If you’re not sure what level of Auto Lighting Optimizer might work best or you’re concerned about the other drawbacks of enabling the filter, consider shooting the picture in the Raw file format. For Raw pictures, the camera applies no post-capture tweaking, regardless of whether this filter or any other one is enabled. Then, by using Canon Digital Photo Professional, the software provided free with the camera, you can apply the Auto Lighting Optimizer effect when you convert your Raw images to a standard file format. (See Chapter 10 for details about processing Raw files.)

Correcting lens vignetting with Peripheral Illumination Correction

Because of some optical science principles that are too boring to explore, some lenses produce pictures that appear darker around the edges of the frame than in the center, even when the lighting is consistent throughout. This phenomenon goes by several names, but the two heard most often are vignetting and light fall-off. How much vignetting occurs depends on the lens, your aperture setting, and the lens focal length.

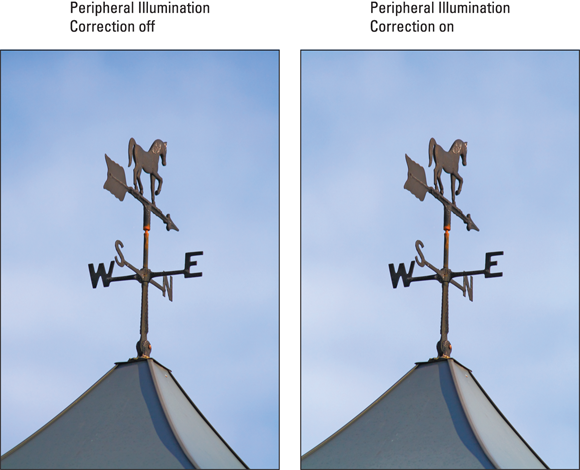

To help compensate for vignetting, your camera offers Peripheral Illumination Correction, which adjusts image brightness around the edges of the frame. Figure 4-32 shows an example. In the left image, just a slight amount of light fall-off occurs at the corners, most noticeably at the top of the image. The right image shows the same scene with Peripheral Illumination Correction enabled.

Now, this “before” example hardly exhibits serious vignetting — it’s likely that most people wouldn’t even notice if it weren’t shown next to the “after” example. But if your lens suffers from stronger vignetting, Peripheral Illumination Correction can help correct the problem.

The adjustment is available in all your camera’s exposure modes. But a few factoids need spelling out:

- The correction is available only for photos captured in the JPEG file format. For Raw photos, you can choose to apply the correction and vary its strength if you use Canon Digital Photo Professional to process your Raw images. Chapter 10 talks more about Raw processing.

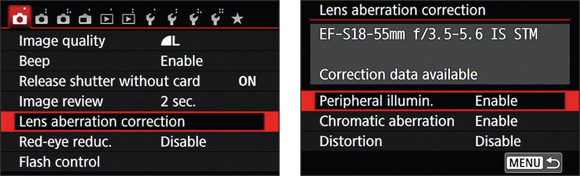

For the camera to apply the proper correction, data about the specific lens must be included in the camera’s firmware (internal software). You can determine whether your lens is supported by opening Shooting Menu 1 and selecting Lens Aberration Correction, as shown on the left in Figure 4-33. Press Set to display the right screen in the figure. If the screen reports that correction data is available, as in the figure, the feature is enabled by default.

If your lens isn’t supported, you may be able to add its information to the camera; Canon calls this step registering your lens. You do this by cabling the camera to your computer and then using some tools included with the free EOS Utility software, also provided with your camera. We must refer you to the software manual for help on this bit of business because of the limited number of words that can fit in these pages. (The manuals for all the software are located on one of the three CDs that ship in the camera box.)

If your lens isn’t supported, you may be able to add its information to the camera; Canon calls this step registering your lens. You do this by cabling the camera to your computer and then using some tools included with the free EOS Utility software, also provided with your camera. We must refer you to the software manual for help on this bit of business because of the limited number of words that can fit in these pages. (The manuals for all the software are located on one of the three CDs that ship in the camera box.)

- For non-Canon lenses, Canon recommends disabling Peripheral Illumination Correction even if correction data is available. You can still apply the correction in Digital Photo Professional when you shoot in the Raw format.

In some circumstances, the correction may produce increased noise at the corners of the photo. This problem occurs because exposure adjustment can make noise more apparent. Also, at high ISO settings, the camera applies the filter at a lesser strength — presumably to avoid adding even more noise to the picture. (See the earlier “ISO affects image noise” section and the following section for an understanding of noise and its relationship to ISO.)

In some circumstances, the correction may produce increased noise at the corners of the photo. This problem occurs because exposure adjustment can make noise more apparent. Also, at high ISO settings, the camera applies the filter at a lesser strength — presumably to avoid adding even more noise to the picture. (See the earlier “ISO affects image noise” section and the following section for an understanding of noise and its relationship to ISO.)

Dampening noise

Noise, the digital defect that gives your pictures a speckled look (refer to Figure 4-5), can occur for two exposure-related reasons: a long exposure time and a high ISO setting. Your camera offers two noise-removal filters, one to address each cause of noise. However, you can control whether and how they’re applied only in the P, Tv, Av, and M modes; in other modes, the camera makes the call for you.

The next two sections explain a little more about these two filters. But before you explore them, realize that many photo editing programs have pretty good noise-removal filters also, so the in-camera noise filters aren’t your only solution to the problem. Especially if you shoot in the Raw file format, you can often get excellent anti-noise results when you process the Raw files. (See Chapter 10 for help with processing of your camera’s Raw files.)

Long Exposure Noise Reduction

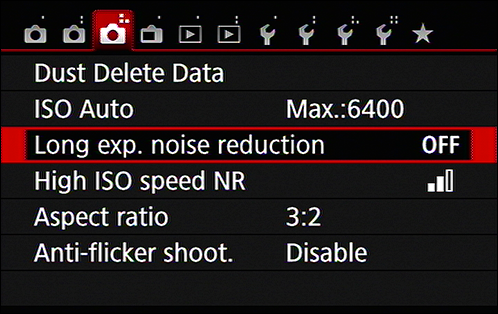

This filter, found on Shooting Menu 3 and featured in Figure 4-34, goes after the type of noise that’s caused by a slow shutter speed. The settings work as follows:

- Off: No noise reduction is applied. This setting is the default.

- Auto: Noise reduction is applied when you use a shutter speed of 1 second or longer, but only if the camera detects the type of noise that’s caused by long exposures.

- On: Noise reduction is always applied at exposures of 1 second or longer. (Note: Canon suggests that this setting may result in more noise than either Off or Auto when the ISO setting is 1600 or higher.)

Long Exposure Noise Reduction can be fairly effective at reducing noise, but it has a pretty significant downside because of the way it works. Say that you make a 30-second exposure at night. After the shutter closes at the end of the exposure, the camera takes a second 30-second exposure to measure the noise by itself, and then subtracts that noise from your real exposure. So your shot-to-shot wait time is twice what it would normally be. For some scenes, that may not be a problem, but for shots that feature action, such as fireworks, you definitely don’t want that long wait time between shutter clicks.

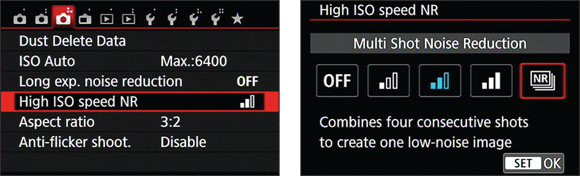

High ISO Speed Noise Removal

This filter, also found on Shooting Menu 3 and spotlighted in Figure 4-35, attempts to do just what its name implies: eradicate the kind of noise that’s caused by using a very high ISO setting. You can select from these settings:

- Off: Turns off the filter

- Low: Applies a little noise removal

- Standard: Applies a more pronounced amount of noise removal; this setting is the default

- High: Goes after noise in a more dramatic way

- Multi Shot: Tries to achieve a better result than High by capturing four frames in a quick burst and then merging them together into a single JPEG shot (more about this option momentarily)

As with the Long Exposure Noise Reduction filter, this one is applied after you take the shot, slowing your capture rate. In fact, using the High or Multi Shot setting for High ISO noise removal reduces the maximum frame rate (shots per second) that you can click off.

It’s also important to know that High ISO noise-reduction filters work primarily by applying a slight blur to the image. Don’t expect this process to eliminate noise entirely, and expect some resulting image softness. You may be able to get better results by using the blur tools or noise-removal filters found in many photo editors because then you can blur just the parts of the image where noise is most noticeable — usually in areas of flat color or little detail, such as skies.

So what about this mysteriously named Multi Shot setting? Canon promises that this setting delivers a better result than the High setting by capturing a burst of four images and merging them into a single JPEG frame, similar to the result of using the Handheld Night Scene mode detailed in Chapter 3. But choosing the option has so many caveats that you may find it not worth the trouble:

- Flash is not possible.

- The feature is off-limits when any of the following are enabled: Long Exposure Noise Reduction, Auto Exposure Bracketing, or White Balance Bracketing.

- You can’t use the feature with the Bulb exposure setting (the manual exposure shutter speed that keeps the shutter open as long as you press the shutter button).

- The merged images may not align properly, resulting in ghosting or blurring, if there’s any camera shake during the exposures. So for the best results, use a tripod. In addition, any moving objects may also appear blurry, so this feature works best with still-life and landscape shots.

- The setting automatically reverts to Standard if you turn off the camera, switch to a fully automatic exposure mode or Movie mode, or set the shutter speed to Bulb.

- Direct printing of shots taken with this setting isn’t possible. Okay, so that’s not a biggie for most folks; see Chapter 10 for more information about direct printing nonetheless.

- Your end result is a JPEG photo, even if the Image Quality setting is set to Raw or Raw+JPEG. So if you’re a Raw fan, don’t use this setting.

Our take is this: If you have a tripod and you want to experiment with the Multi Shot setting, it’s worth a try if you don’t need fast shot-to-shot capture time and your scene doesn’t include moving objects. Otherwise, we’d stick with High or even Standard and either live with the resulting noise or clean it up using photo software after downloading.

If you do opt for the Multi Shot setting, you see a little multi-box symbol during playback next to the Metering Mode symbol when you set the Playback mode to the Shooting Information or Histogram modes. See Chapter 9 for help with the playback display modes.

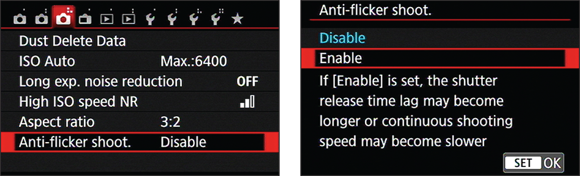

Anti-Flicker Shooting

As mentioned in Chapter 1, you have the option of enabling Flicker Detection from Setup Menu 2. This warns you if the camera detects flickering lights that could cause exposure problems. What happens is that the lights, by design, cycle on and off rapidly. (Technically, the camera is designed to detect flickering at 100Hz or 120Hz.) It happens too quickly for you to notice, but at the speeds your camera works at, the exposure will be thrown off if it meters in an on cycle (shown on the left in Figure 4-36) and takes the photo in an off cycle (shown on the right in the figure).

In addition to detecting when the conditions are right to cause this problem, you can set the camera to work around the on/off cycles. First, you have to be in a Creative Zone shooting mode (P, Tv, Av, or M). Set the Mode dial to one of those shooting modes. Then, navigate to Shooting Menu 3 and highlight the Anti-Flicker Shooting option (shown on the left in Figure 4-37). Press Set and select Enable from the following screen (shown on the right in Figure 4-37).

Note the warnings that are displayed on the screen about the possibility of lag. This is caused by the camera timing the exposure just right. In addition, Anti-Flicker Shooting is not possible in Live View or Movie modes. You can set the feature in a Creative Zone mode and then switch to a Basic Zone mode and it will still work; you will not receive any notification, however.

Locking Autoexposure Settings

To help ensure a proper exposure, your camera continually meters the light until the moment you press the shutter button fully to shoot the picture. In autoexposure modes — that is, any mode but M — the camera also keeps adjusting exposure settings as needed.

For most situations, this approach works great, resulting in the right settings for the light that’s striking your subject when you capture the image. But on occasion, you may want to lock in a certain combination of exposure settings. For example, perhaps you want your subject to appear at the far edge of the frame. If you were to use the normal shooting technique, you would place the subject under a focus point, press the shutter button halfway to lock focus and set the initial exposure, and then reframe to your desired composition to take the shot. The problem is that exposure is then recalculated based on the new framing, which can leave your subject under- or overexposed.

The easiest way to lock in exposure settings is to switch to M (manual exposure) mode and use the same f-stop, shutter speed, and ISO settings for each shot. In manual exposure mode, the camera never overrides your exposure decisions; they’re locked until you change them.

The easiest way to lock in exposure settings is to switch to M (manual exposure) mode and use the same f-stop, shutter speed, and ISO settings for each shot. In manual exposure mode, the camera never overrides your exposure decisions; they’re locked until you change them.

But if you prefer to stay in P, Tv, or Av mode, you can lock the current autoexposure settings by using the AE (autoexposure) Lock function. Here’s how to do it:

Press the shutter button halfway.

If you’re using autofocusing, focus is locked at this point.

Press the AE Lock button.

Press the AE Lock button.

Exposure is now locked and remains locked for 4 seconds, even if you release the AE Lock button and the shutter button.

To remind you that AE Lock is in force, the camera displays a little asterisk at the left end of the viewfinder or, in Live View mode, in the lower-left corner of the display. If you need to relock exposure, just press the AE Lock button again.

Note:

If your goal is to use the same exposure settings for multiple shots, you must keep the AE Lock button pressed during the entire series of pictures. Every time you let up on the button and press it again, you lock exposure anew based on the light that’s in the frame.

One other critical point to remember about using AE Lock: The camera establishes and locks exposure differently depending on the metering mode, the focusing mode (automatic or manual), and on an autofocusing setting called AF Point Selection mode. (Chapter 5 explains this option thoroughly.) Here’s the scoop:

One other critical point to remember about using AE Lock: The camera establishes and locks exposure differently depending on the metering mode, the focusing mode (automatic or manual), and on an autofocusing setting called AF Point Selection mode. (Chapter 5 explains this option thoroughly.) Here’s the scoop:

- Evaluative metering and automatic AF Point Selection: Exposure is locked on the focusing point that achieved focus.

- Evaluative metering and manual AF Point Selection: Exposure is locked on the selected autofocus point.

- All other metering modes: Exposure is based on the center autofocus point, regardless of the AF Point Selection mode.

- Manual focusing: Exposure is based on the center autofocus point.

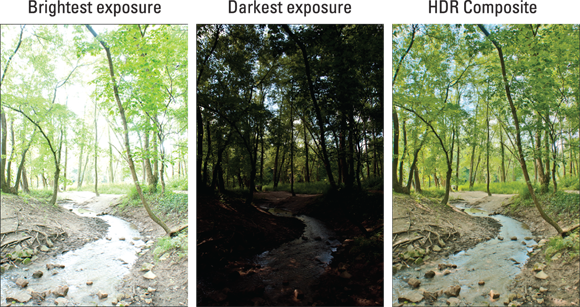

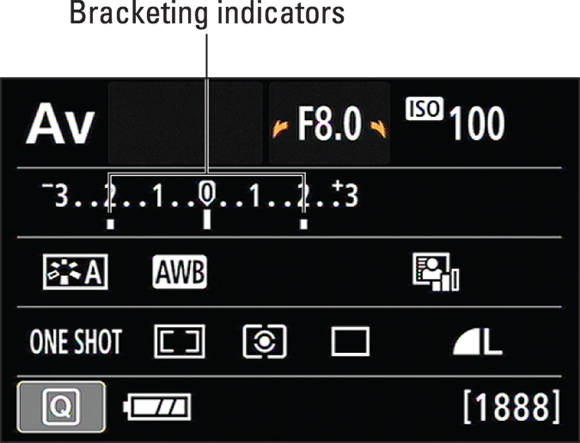

Bracketing Exposures Automatically