In the way that it presents the area west of the Madeira, the map of Amazonia is a diagram of its initial settlement. The history of the new region, rather than being written, must be drawn. It isn’t read, it is seen. It can be summarized in the long, curving arcs of the Purus, the Juruá, and the Javari.

These are natural lines of communication and transportation that no others can rival in supporting a far-flung dominion. Geometrically, the beds of those river valleys, running at an angle to the meridians and almost parallel to each other—generally southwest to northeast—enable movement forward in latitude and longitude at the same time. Physically, apart from artificial obstacles created by their current state of abandonment, they stretch out unimpeded. Their most important dimensions are, however, blocked. In most Amazonian rivers, and especially in the Ucayali Valley, accumulating impediments have given rise to strange geographical terms. One cannot cite just one of them. Not dizzying pongos nor steep rapids nor swirling whirlpools, nor even maddening “devil’s turns.”

Hence this highly indicative historical consequence: while on the Tocantins, the Tapajós, the Madeira, and the Rio Negro, settlement begun in colonial times has struggled or has even become retrograde—a fact profiled in the ruins of the small settlements, fallen in with undermined banks—here it has progressed in an unforeseeable a manner, conforming to the topography of the river banks. In fewer than fifty years it has led to the expansion of national borders.

It was inevitable. Upon entering the Purus or the Juruá, the foreigner would not see himself as lacking resources for an exceptional commercial venture. A practical canoe and pole or paddle would outfit him for the most amazing voyage. The river would bear him along, guide him, provide nourishment, and protect him. He needed only to gather the precious products from the forest banks, fill his primitive boats with them, and return back downstream, sleeping on top of a fortune acquired with no work. Thanks to its millennarian warehousing of riches, the profligate land has made cultivation unnecessary. It has opened itself up to man with marvelous watery roadways. It has imposed on him only the task of harvesting. In short, nomadism is a logical course for him to take.

The name montaria, “mount,” given to his light, swift dugout, is apt. It has related him to these level solitudes much as the horse adjusts the Tartar to the steppes. This single difference: while the Kalmuck has, in the infinity of points on the horizon, an infinity of routes to attract him to a nomadism that can spread out in any direction from his yurt—which, even after it is moved to a new location seems motionless on the unending circle of the plains—the Amazonian water pilot, subject to linear routes, held to immutable directions, remains for a long period of time trapped between the banks of rivers. He can detour barely a few leagues, on the tributaries’ lateral courses. In contrast to common belief, those complexly interwoven networks do not mix the waters of the different rivers by means of anastomoses winding across the marshy plains. The side channel always returns to the principal bed from which it split off. The igarapé ends up in the lake it fed at high water so that it could be fed by it in turn at low water, running in opposite directions according to the season of the year; or it empties out on swampy flatlands hidden by the amphibian florula of the vine-choked igapós. Between one watercourse and the other a strip of forest stands in place of the nonexistent mountain. It is the divider. It separates. It divides the masses of settlers who have come to the area into long, isolated roadways.

Along with the highly favorable natural conditions, then, the following downside has been observed: man, instead of mastering the land, becomes enslaved to the river. The population has not expanded; it has stretched. It has progressed in long lines or turned back on itself, all without leaving the waterways along which it is channeled—tending to become immobile while appearing to progress. Progress, despite the many advances and retreats, is in fact illusory. The adventurers who set out, penetrate deep into the land, and exploit it merely return along the same routes, or follow again, monotonously, the same invariable itineraries. In the end, the short but highly restless history of these new regions, a few variants aside, has imprinted itself totally, concretely, according to those long lines opening to the southwest: three or four channels, three or four river profiles, snaking endlessly through a wilderness.

Now this discouraging social dimension, created principally by river conditions otherwise so favorable, can be corrected by the transverse linking of the great valleys.

The idea is neither original nor new. With admirable foresight the rough settlers of those distant areas put it into practice long ago with the creation of the first portages.

The portage—legacy of the heroic activity of the bandeirantes shared today by the Amazonian, the Bolivian, and the Peruvian—is a cross path that runs from the terrain of one river course to that of another.

Originally twisting and short, running out in the density of the forests, the portage reflects the indecisive march of the society that, nascent and tottering, first abandoned the river’s lap to walk on its own. And it has grown along with that society. Today those narrow courses a meter wide, cleared by bush knife, running in all directions, intertwining in innumerable turns and crossings, linking the separate tributaries of all the headwaters, from the Acre to the Purus, from the Purus to the Juruá, from it to the Ucayali, trace the contemporary history of the new territory in a way totally opposite to earlier subservience to the determining power of the great natural arteries of communication.

In their twists and turns, determined by the highest lines of the low banks, one feels a strange, anxious movement—a movement of revolt. In treading them, man is a rebel. He aggresses against the generous and treacherous nature that has enriched and has killed him. Those old supports that are the rivers so repel him that in this greatest of Mesopotamias he practices the anomaly of navigating on dry land. Or, rather, the following transfiguration of that act: he transports from one river to another the boat that previously transported him. In fine, in an increasing affirmation of will, he extends from one river to the next, reconceived with the aid of the infinite links of the igarapés, the imprisoning network of ever smaller and more numerous connections that will shortly deliver over to him a mastered land.

And from the Acre to the Yaco to the Tauamano to the Orton, from the Purus to the Madre de Dios to the Ucayali to the Javari, treading freely all corners of the territory, the Acreans, liberated from the old mark of unification with the distant Amazon that had kept them dispersed and subordinate to the remote coast, as they travel each of those daring roads are securing a tangible symbol of independence and possession.

Let us take one example of witness, by a foreigner.

In 1904 the Peruvian naval officer Germano Stiglich encountered various Brazilians on the Javari. They astonished him with the simple narrative of a routine crossing, in the light of which his most far-flung travels as an eminent explorer were greatly diminished. He registered it in one of his reports: those frontiersmen entered at the Javari and went up the Itacoai to its headlands. They went from there across country searching for the headwaters of the Ipixuna, found them, crossed them, and came down that small tributary to reach the Juruá. They then traveled on it to Sao Felipe, where they turned and went onto the Tarauacá, the Envira, and the Jurupari, as far as their light canoes could go. They left them there and again set out across country to reach the Purus in the environs of Sobral. They came down the great river for 760 kilometers in a boat to the mouth of the Ituxi. Following that river, after another cross-country portage, they reached the Abunã, which they came down, finally reaching the left bank of the Madeira.

That route, if one adds 20 percent to the straight measurement to account for actual distance traveled, is calculable at a length of three thousand kilometers, or twice the traditional path of the bandeirantes between Sao Paulo and Cuiabá. Those obscure pioneers had prolonged into our day the heroic tradition of incursions—the only aspect of our History that is unique.

That itinerary, however, is very long, turning as it does in overly wide arcs. Let us cut it down on the basis of some accurate data.

Setting out from Remate dos Males, near Tabatinga on the Javari, the traveler can at any time of year ply the Ituí in one day, covering 140 kilometers. He can then proceed southeast by land on solid roads over the 190-kilometer portage that cuts across the various headwaters of the Jutaí and ends in São Felipe on the banks of the Juruá. It is only five days’ march. He can go in a boat up the Tarauacá to the mouth of the Envira and from there to the mouth of the Jurupari, seeking its headwaters. It is a trek that would cover at maximum 350 kilometers, which he could accomplish in little more than a week. He makes his way along the short portage that would bring him to the Furo do Juruá and, going down it for two days, he would reach the Purus. From there to the mouth of the Yaco it is 392 kilometers, which could be run in two days by launch, if the needed minimal upkeep of the river were performed. The headquarters of the prefecture of the Upper Purus, twenty-four kilometers away, can be reached in two hours by river. From there, over the Oriente portage, with a length of twenty-five leagues, normally covered in five days, one can reach the rubber tract of Bajé on the left bank of the Acre. Crossing that river and continuing east across the last tributaries of the Iquiri and the Campos do Gavião, the traveler can go to the Abunã, downstream from the mouth of the Tipamanu and thence to the Beni, at the confluence of the Madeira, covering close to 300 kilometers by land in eight days.

In this fashion, in little more than a month of travel, covering 907 kilometers by water and 660 by land, he can go diagonally from Tabatinga to Villa Bella, from one end of Amazonia to another, in an itinerary of 250 leagues.

Those numbers lack the rigor of real measurement, but the variance cannot be more than perhaps one-tenth, except in the case of the fallible data relating to navigation of the Tarauacá and the overland trek from the Jurupari to the Purus.

Let us exclude them, then, in this variant: departing from the same point on the banks of the Javari and plying the Itacoaí to its highest headwaters, the traveler can use the old portage of the Ipixuna, which will take him to the Juruá and to Cruzeiro do Sul, capital of the Department, in a march that is not much longer than the prior one through São Felipe.

Going from Cruzeiro do Sul to the headquarters of the Departments of the Purus and of Acre eliminates the problems in the former route involved with the precarious and exhausting river trip.

The long rectilinear segment of 605 kilometers that follows the Cunha Gomes line is precisely the planned route of a notable portage that would link together the three administrative seats. Allowing a generous 20 percent on that distance, one calculates a length of 726 kilometers, or exactly 110 leagues, which can be covered by horse in fewer than twelve days.

It should be observed in passing that this project is not one drawn up according to the arbitrary lines to which “map explorers” are accustomed—according to the “well-known gesture that had Czar Nicholas I scratching out a road from St. Petersburg to Moscow with his thumbnail.”

It rests instead on practical knowledge—absent azimuths or aneroid readings, but concrete nonetheless and therefore definitive. The first segment, perpendicular to the valley of the Tarauacá, planned by General Taumaturgo de Azevedo, is now in great part open due to the activity of a seringueiro from Cocamera. It stretches over terrain so favorable to land travel that, once the road is complete, as the former prefect declares in his penultimate report, “one will travel from the Juruá to the Tarauacá on horseback in four days.” To make such a trip currently “in a steamboat that makes few stops and turns at the mouth of the Tarauacá would take at least fifteen days.”

The intermediate segment, from Barcelona or Novo Destino to the confluence of the Caeté into the Yaco, studied by the prefecture of the Upper Purus, would be easy to execute over a small, flood-free high plain. And the last, from the Yaco to the Acre, has long had regular traffic.

In this manner the great 726-kilometer roadway linking the three departments and easily extendable on one side all the way to the Amazon by means of the Javari and on the other side all the way to the Madeira by means of the Abunã has been completely reconnoitered and in great part is already in use.

The intervention of the federal government is urgently needed to perform the basic task of linking together the several discrete initiatives and giving incentive to the project.

The project should, however, consist in the establishment of a railroad—the only such road both urgent and indispensable in the entire Acre territory.

Let us anticipate an initial objection.

The physical geography of the Amazon is always cited as an obstacle to this kind of project. But those who adduce it, in arguments that I do not consider it necessary to reproduce here, must be ignorant of Indian railways. In fact, in Hindustan proper the surface features, the alluvial soil made up of sand and clay laid down in indiscriminate deposits, and the climatic conditions are almost identical to ours. There, as in Amazonia, the rivers are characterized by their large size, excessive volume at high water, amount of flooding, and changeable channels in ever wandering riverbeds. The hydrography of the innumerable nullahs winding through the terrain repeats the chaotic hydrography of our igarapés. Indeed, the Purus, the Juruá, the Acre, and their tributaries do not vary as much in their courses and regimen as do the Ganges and the rivers of the Punjab, the bridges over which represented the greatest challenge that British engineering had to overcome.

In India, just as in our case, there was no shortage of professionals who were intimidated by the problems presented by the natural conditions—forgetting that engineering exists precisely to overcome such problems. When the “Kennedy memorandum,” which was the germ of the Hindu transportation system, was discussed, Colonel Grant of the Bombay Corps of Engineers engaged in a wry bit of humor by proposing that for the entire length of the line the tracks be suspended eight feet above the ground by means of regular series of chains on rigid facing posts. He thus challenged the magnificent humor of his phlegmatic colleagues. The hardy railroadmen met that challenge in overwhelming fashion: with the West Indian Peninsular Railroad. And in so doing they raised railroad engineering to new heights, fulfilling one of its civilizing formulas, first enunciated by Mac-George: “In every country it is necessary that railway should be laid out with reference to the distribution of the population and to the necessities of the people, rather than to the mere physical characteristics of its geography.”

Now in our case even the physical and geographical characteristics are favorable.

Unlike the rail beds in the south of our country, the road from Cruzeiro do Sul to the Acre will not go parallel to the general direction of the great valleys because it has a different function. In the south, particularly in São Paulo, the rail lines describe the classical lines of penetration, moving the people toward the heart of the country. In this corner of Amazonia, as we have seen, that function is performed by the watercourses. The projected rail line will have the function of moving from one place to another the people who already live here. Its function is that of auxiliary to the rivers. Therefore it should cut across the valleys.

Hence this necessary consequence: it has to follow the low terrain that divides the lateral tributaries and in so doing will avoid the obstacles presented by the confused hydrography.

By contrast, south of the eighth parallel, the facies of the enormous Amazonian várzea still predominates but in attenuated form. The tumultuous inconstancy of the waters does not deploy itself in as many curves or as changeably. The terrain, stretching out in gentle rolling hills with an average height of two hundred meters, is generally solid and stands above the high water level. I have walked it at various points. It is visibly clear that one is standing on older, more defined, and more stable formations than those of the immense post-Quaternian plain on which one can still sense the last geological transformation of the Amazon, in its inevitable conflict between the inconstant watercourses and the unstable várzea.

Beyond this, the natural obstacles will be either reduced or nearly eliminated by choosing routes that take them well into account. The initial installation of the rail line in question should be carried out on the basis of the least costly technical specifications: a single, reduced-gauge line—0.76 meters, 0.91 meters, or, in the maximum, one meter between rails. That will allow for the steepest grades and the sharpest curves, giving the line the flexibility to make turns in order to seek the highest and most stable ground, which will keep the grade above high water marks along routes approximately at land level. It should start off as have the greatest current railways: at maximum, rails at eighteen kilos per running meter, able to handle lightweight locomotives of fifteen to twenty total tons adhesion weight; curves with down to a fifty-meter radius; and grades of up to 5 percent according to the character of the land.

There is no railway better in this regard than the Central Pacific in Nevada, with its narrow gauge and absence of ballast, twisting, with similar light rails, over ninety-meter curves and winding along slopes with unclassifiable ramps. Or the Trans-Siberian Railroad, where thirtyton locomotives pulling 1/6 adhesion weight over nineteen-kilo rails and traveling with a speed of twenty kilometers per hour not infrequently are forced to go in reverse when they meet harsh headwinds off the steppes.

To be sure, such a superstructure, to which one must add the imperfectness of the rolling stock, both traction and transport, will support only a significantly reduced traffic capacity. But, much like the Union Pacific, the Acrean Line is not designed to meet the demands of some nonexistent clientele but to create the one that should exist.

Like the American lines, it should be built quickly in order then to be rebuilt slowly.

Such a process is in fact the norm.1 All the great rail lines, in their beginnings have avoided the most formidable obstacles they faced by using the most basic resources at their disposal to cross the lowest places and avoid the biggest cuts. That process has enabled them to continue laying track, first put down like wild, imperfect roads of battle against the wilderness. And as though to justify that assertion, we can remind ourselves that the first engineer of the same rudimentary structures of wood palings and bridges—which are being built today just as they were two thousand years ago, rough-hewn and erected in lines on the styli fixi of round posts—was Caesar.

The roads then evolve and grow, improving the various parts of their complex structure, as though they were enormous living organisms being transfigured by the very life and progress they awaken.

That is what will happen with the line I project here. Its social implications are evident from the first words of this article. Those implications have not been set out in detail because many of them are intuitive and involve multiple effects, which run from the simple concrete fact of population redistribution—siting with greater certainty the nuclei of settlements or agricultural areas and delimiting legally the unassigned lands—to quicker, less cumbersome, and firmer administration of public authority, which currently is triply divided, spread across the three administrative seats that are required purely because of the vicissitudes of geography.

Such results would in and of themselves justify exceptional expenditures.

The following, however, are more open to conjecture. After immediate action by the government and definitive planning, everything leads one to believe that the three principal sections that the railway would include—the segments from the Juruá to the Purus, from the Purus to the Yaco, and from there to the Acre—engaged simultaneously by our military engineers and favored by the easy transport of the necessary materials along those rivers themselves, can be constructed in an expeditious manner and with the resources of local income.

Its engineering works will be insignificant, the most serious being the construction of small bridges and earthworks as well as the extensive clearing, forty meters wide, to achieve maximum clearance for the roadbed.2

Not only will the line not need extensive developments to climb high ground but it will also not need tunnels to go through such ground, or major cuts, or viaducts, or even the three great bridges—over the Tarauacá, the Purus, and the Yaco—that might at first seem absolutely indispensable. The station at the terminus of each of the three aforementioned segments can serve as well as the station for navigation of its corresponding river, and, in the first stage of development, the transfers from one bank to the other will be able to be made without significant disturbance of what will naturally be relatively sparse traffic.

Thus costly services will be able to be put off, to be effected gradually in the future according to circumstances. The road will grow with the population. And even though it may stretch out over the enormous distance of 726 kilometers and be limited to one track plus the necessary sidings, allowing the minimal velocity of twenty kilometers per hour, it will be negotiable end to end in a mere thirty-six hours—which would increase to forty-eight when the hours necessary to cross the rivers are added in.

The trip from Cruzeiro do Sul to the Acre will thus be doable in two days. Currently that trip, in the most propitious seasons of the year, takes more than a month.

The conclusion is inalterable. Let us not waste time enumerating the enormous effects.

Let us instead examine another dimension of the question.

Americans have defined railroad engineering in this concise and irreducible formula: “the art of making a dollar earn the highest possible interest.”

Let us bow to that barbarously utilitarian precept.

The economic value of the proposed project is incalculable. That fact can be evidenced in multiple forms, those most worthy of credit being—naturally—the furthest in the future: ones deriving from the inevitable progress of the impacted regions.

It would take too long to list each and every effect. Let us indicate one only—and one that is proximate, immediate, and thus recommends itself to even the most resistant outlooks.

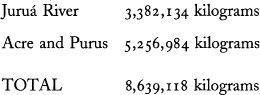

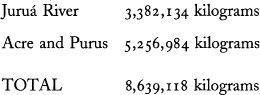

For the next-to-last business year of 1905, according to the most reliable documents, the harvest of rubber in the three affected departments, between the Cunha Gomes line and the neutral strip, was as follows:

With the current prices varying between the extremes of 3,865 reis and 6,346, one can estimate, in round numbers, an average of 5,000 per kilo and, as a result, the total value of the production at 43,195,590,000 reis, resulting in export tax revenues (23 percent) of 9,934,985,700.

The figures are clear and undeniable.

Now these yields will tend to double, not by dint of some development in the distant future but rather through the simple fact of opening up the rail line.

The demonstration is straightforwardly graphic and readily visualized.

The tapping of the rubber trees, as everyone knows, generally operates in the long strips of the forest mass that flank the two banks of the rivers. The “centers” adjacent to the most highly developed barracões are few and ordinarily not very distant. Strictly speaking, these are not surface areas being harvested from but only strips. And with the aid of the existing data, they can be measured with reasonable accuracy. Along the Purus, they stretch from Barcelona to Sobral; on the Yaco, from Caeté to a little beyond the seringal of São João; from Cruzeiro do Sul to the mouth of the Breu on the Juruá; and on the Acre, from Porto Acre to not far above the confluence of the Xapuri. If we add to those large strips the smaller ones on the Tarauacá, the Envira, and the Jurupari, we get approximate total dimensions of 150 leagues of strips being harvested, presuming that all are currently in operation—which is not always the case. That extension is, then, a maximum; it is the graphic, visible definition of the current economic import of the territory.

It derives, as one can see, merely from the courses of the rivers.

The new rail line will, naturally, itself represent a “path” providing entry of new workers for the quick harvest of products that up to today have not required any effort at cultivation. Rather than a railroad it will in fact be an enormous, 120-league “path,” almost the total size of the stretches currently being harvested. Now, in contrast to the elastic Castilloas that produce caucho, the Heveae brasilienses are characterized by a rather even distribution throughout the forests. Thus, reliably calculated, the proportion necessary to quickly reimburse the immediate cost of the planned rail line, which will inevitably be built in a more or less proximate future according to the route I have traced out, cannot be considered conjectural.

One must add to its value in and of itself those values deriving from its route and that route’s articulation with other lines of transport.

The Madeira-Mamoré rail line, once completed, will attract it eastward, irresistibly, through the commonplace phenomenon of the attraction of systems. It will, then, cross the Acre and go in search of the Madeira at the confluence of the Abunã, or at Villa Bella, suddenly doing away with all the inconvenience associated with three long, roundabout river voyages. At the same time, at its other end, spreading out westward, going up the Moa and passing over the low hills of Contamana, it will reach the Ucayali, transferring to the Madeira port town of Santo Antônio part of the commercial gravitation of Iquitos. At that point the very modest “Transacrean Line,” almost local in character, designed to deal with peculiar hydrographic conditions, will have been transformed into an international roadway with an extraordinary destiny.

Let us briefly consider a less pleasant side of this matter.

In border regions strategic value is a necessary supplement to the highest requirements that any communications and transportation system might possess. That value can be measured, evaluated, and studied with a cold, technical eye and without any aggressive intent. In our day in America, such intent would not only be reprehensible but frankly ridiculous.

Let me, then, present the matter in unvarnished and matter-of-fact terms, my only rhetoric being of the sort that might be invoked to solve a problem in basic geometry.

Consider the general directions of the Purus, the Juruá and the Javari on the map and then those of the Madre de Dios and the Ucayali. The former group, in what we might term their uniform, equally spaced courses, deploy themselves like so many sectoring ditches; they subdivide the land. The last two are long, unifying ties; they encompass the land. Above its confluence with the Marañon, the Ucayali turns eight degrees to the south, then veers to the east as the Urubamba and, dividing into the Mishagua and the Serjali, almost anastomoses with the last of the westernmost sources of the Madre de Dios. That river, above the confluence of the Beni, which carries it on to the Madeira, breaks into an extensive network of curves that cut through seven degrees of longitude to the west; it then turns slightly to the north through the Manú thalweg and, dividing into the Caspajali and the Shauinto, almost meets the last western sources of the Ucayali. Between the two, a piece of ground a mere five miles wide: the Isthmus of Fitzcarrald. The two rivers thus encircle almost the entirety of Amazonia, an area of nearly 1,100,000 square kilometers, forming what, viewed this way, is the largest peninsula on earth.

That hydrographic picture is one of a huge pincers that encircle and grip a piece of continent in arms articulated at that isthmus.

It is a disposition that is highly unfavorable to the security and defense of our borders in that area.

Let me straightforwardly demonstrate the point.

Initially there seems to be the opposite illusion. If we hypothesize a conflict with the neighboring countries, we might at first glance place stock in the incomparable value of those three or four extensive roads. Entering by the Purus, by the Acre, by the Juruá, and even by the Javari, four expeditionary forces could be mobilized and could establish multiple other points quite distant from each other in a 700-kilometer swath of operations extending from the northeast to the southwest. Indeed, those watercourses recall the strategic routes of the Roman “consular ways.” They bisect the border forcefully, in perpendicular.

That effect is, however, canceled out by the huge surround of the Madre de Dios-Ucayali combination.

A simple contrast of the geometrical positions is revealing.

In point of fact, the perpendicular deployment of our avenues of access, striking the border area head-on and cutting straight across it, contrasts with the parallel relationship between the border and the two enormous rivers that embrace it.

Hence this corollary: the necessarily distant end points that would be our objectives at the end of river navigation would represent for our adversaries mere points along their lines of operation. To guarantee ourselves a given number of positions we would need that same number of combat units and each would have to make that perpendicular journey. The adversaries, by contrast, with a few light, shallow-draft launches could defend all of our points of entrance at once.

In the case of fortunate outcome, victory on our part would have had to do with conquering on the field of combat. For them, it would be in delaying the outcome. Defeated at any of our isolated points without lateral connections with our other forces, we would have it as our only recourse to retreat, leaving that point of entry open to invasion. The opponent, if he is beaten at one point, can re-form in lightning remobilizations by moving back to the Pachitea by means of the Ucayali, or to the Inambari by means of the Madre de Dios.

These are undeniable conclusions. They are summarized by yet another, higher one that synthesizes them all. It is that, apart from the hypothesis of a daring offensive against the foreign country, the expeditionary forces on the Juruá, the Purus, and the Acre, once they arrive at their distant destinations, are condemned to immobility—put in reactive positions, unable to surveille the stretches of forest that separate them. By contrast, the Ucayali and the Madre de Dios, from Nauta to the Isthmus of Fitzcarrald and from there to the mouth of the Beni, are roads that offer no impediment to ongoing patrols and generalized control.

Such different resources are not even comparable. Those last two rivers, in their rapid linking of all the elements of resistance and in facilitating the most complex mobilizations, constitute an unmatched military roadway.

Now, a rail line from Cruzeiro do Sul to the Acre would counter that position of superiority.

Oriented, as it would be, as the cord of that enormous enveloping curve, it would possess some of its same features thus counterbalance its effect.

Demonstration is unnecessary. The geographical image is in and of itself sufficiently indicative.

Beyond this, what should be seen in that projected rail line is, above all else, a great international avenue of civilizing alliance and of peace.

1. For example, even Dr. H. Schnoor, a master who has constructed more than two thousand kilometers of rail line, in a recent discussion at the Engineering Club about the technical conditions of the Madeira-Mamoré, did not hesitate to advise a 0.6-meter gauge; 10-kilogram rails, Decauville type; 20-ton locomotives, 5 percent grades, and 20-meter-radius curves.

These are his exact words: “In my judgment it will be necessary to move ahead laying the track, pushing on in whatever way possible, building wood bridges instead of the complete finished product, in order to then build the final version after the line is laid” (Revista do Clube de Engenharia 7, no. 11 [1905]).

2. This great avenue, at its greatest development, will have a surface of 726,000 meters by 40 meters, or 29,040,000 square meters. Allowing the high-end rate of 50 reis per square meter (twice the amount that Dr. Chrockatt de Sá budgeted for the Madeira-Marmoré), its opening would cost only 1,452,000,000 reis.