There are major uncertainties in estimating the consequences of nuclear war.

1 Much depends on the time of year of the attacks, the weather, the size of the weapons, the altitude of the detonations, the behavior of the populations attacked, and so on. But one thing is clear: the number of casualties, even in a small, accidental nuclear attack, would be overwhelming. If the commander of just one Russian Delta IV ballistic-missile submarine were to launch twelve of its sixteen missiles at the United States, 7 million Americans could die.

2Experts use various models to calculate nuclear war casualties. The most accurate experts estimate the damage done from all three of a nuclear bomb’s sources of destruction: blast, fire, and radiation. Fifty percent of the energy of the weapon is released through the blast, 35 percent as thermal radiation, and 15 percent through radiation.

Like a conventional weapon, a nuclear weapon produces a destructive blast, or shock wave. A nuclear explosion, however, can be thousands and even millions of times more powerful than a conventional one. The blast creates a sudden change in air pressure that can crush buildings and other objects within seconds of the detonation. All but the strongest buildings within 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) of a 1-megaton hydrogen bomb would be leveled. The blast also produces super-hurricane winds that can destroy people and objects like trees and utility poles. Houses up to 7.5 kilometers (4.7 miles) away that have not been completely destroyed would still be heavily damaged.

A nuclear explosion also releases thermal energy (heat) at very high temperatures, which can ignite fires at considerable distances from the detonation point, leading to further destruction, and can cause severe skin burns even a few miles from the explosion. The Stanford University historian Lynn Eden calculates that if a 300-kiloton nuclear weapon were dropped on the U.S. Department of Defense, “within tens of minutes, the entire area, approximately 40 to 65 square miles—everything within 3.5 or 6.4 miles of the Pentagon—would be engulfed in a mass fire” that would “extinguish all life and destroy almost everything else.” The creation of a “hurricane of fire,” Eden argues, is a predictable effect of a high-yield nuclear weapon, but war planners do not take this into account in their targeting calculations.

3Unlike conventional weapons, a nuclear explosion also produces lethal radiation. Direct ionizing radiation can cause immediate death, but the more significant effects are long term. Radioactive fallout can inflict damage over periods ranging from hours to years. If no significant decontamination takes place (such as rain washing away radioactive particles or their leaching into the soil), it will take eight to ten years for the inner circle near the explosion to return to safe levels of radiation. In the next circles, such decay will require three to six years. Longer term, some of the radioactive particles will enter the food chain.

4 For example, a 1-megaton hydrogen bomb exploded at ground level would have a lethal radiation inner circle radius of about 50 kilometers (30 miles) where death would be instant. At 145 kilometers radius (90 miles), death would occur within two weeks of exposure. The outermost circle would be at 400 kilometers (250 miles) radius where radiation would still be harmful but the effects not immediate.

In the accidental Delta IV submarine strike noted above, most of the immediate deaths would come from the blast and “superfires” ignited by the bomb. Each of the 100-kiloton warheads carried by the submarine’s missiles would create a circle of death 8.6 kilometers (5.3 miles) in diameter. Nearly 100 percent of the people within this circle would die instantly. Firestorms would kill millions more (see

table 5.1). The explosion would produce a cloud of radioactive dust that would drift downwind from the bomb’s detonation point. If the bomb exploded at a low altitude, a swath of deadly radiation 10–60 kilometers (6–37 miles) long and 3–5 kilometers (2–3 miles) wide would kill all exposed and unprotected people within six hours of exposure.

5 As the radiation continued and spread over thousands of square kilometers, it is possible that secondary deaths in dense urban populations would match or even exceed the immediate deaths caused by fire and blast, doubling the total fatalities in

table 5.1. The cancer deaths and genetic damage from radiation could extend for several generations.

Source: Bruce G. Blaire, et al., “Accidental Nuclear War—a Post–Cold War Assessment,” The New England Journal of Medicine 338, no. 18 (April 1998): 1326–32.

CALCULATING GLOBAL WAR

Naturally, the number of casualties in a global nuclear war would be much higher. U.S. military commanders, for example, might not know that the commander of the Delta IV submarine had launched by accident or without authorization. They could very well order a U.S. response. One such response could be a precise “counter-force” attack on all Russian nuclear forces. An American attack directed solely against Russian nuclear missiles, submarines, and bomber bases would require some 1,300 warheads in a coordinated barrage lasting approximately thirty minutes according to a sophisticated analysis of U.S. war plans by experts at the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington, D.C.

6 It would destroy most of Russia’s nuclear weapons and development facilities. Communications across the country would be severely degraded. Within hours after the attack, the radioactive fallout would descend and accumulate, creating lethal conditions over an area exceeding 775,000 square kilometers (300,000 square miles)—larger than France and the United Kingdom combined. The attack would result in approximately 11–17 million civilian casualties, 8–12 million of which would be fatalities, primarily from the fallout generated by numerous ground bursts.

American war planners could also launch another set of plans designed and modeled over the nuclear age: a “limited” attack against Russian cities, using only 150–200 warheads. This is often called a “counter-value” attack, and, though using fewer weapons, it would kill or wound approximately one-third of Russia’s citizenry. An attack using the warheads aboard just a single U.S. Trident submarine to attack Russian cities will result in 30–45 million casualties. An attack using 150 U.S. Minuteman III ICBMs on Russian cities would produce 40–60 million casualties.

7If, in either of these limited attacks, the Russian military command followed their planned operational procedures and launched their weapons before they could be destroyed, the results would be an all-out nuclear war involving most of the weapons in both the U.S. and Russian arsenals. The effects would be devastating. Government studies estimate that between 35 to 77 percent of the U.S. population would be killed (105 to 230 million people, based on current population figures) and 20 to 40 percent of the Russian population (28 to 56 million people).

8A 1979 report to Congress by the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment, The Effects of Nuclear War, noted the disastrous results of a nuclear war would go far beyond the immediate casualties:

In addition to the tens of millions of deaths during the days and weeks after the attack, there would probably be further millions (perhaps further tens of millions) of deaths in the ensuing months or years. In addition to the enormous economic destruction caused by the actual nuclear explosions, there would be some years during which the residual economy would decline further, as stocks were consumed and machines wore out faster than recovered production could replace them.…

For a period of time, people could live off supplies (and, in a sense, off habits) left over from before the war. But shortages and uncertainties would get worse. The survivors would find themselves in a race to achieve viability … before stocks ran out completely. A failure to achieve viability, or even a slow recovery, would result in many additional deaths, and much additional economic, political, and social deterioration. This postwar damage could be as devastating as the damage from the actual nuclear explosions.

9

According to the report’s comprehensive analysis, if production rose to the rate of consumption before stocks were exhausted, then viability would be achieved and economic recovery would begin. If not, then “each postwar year would see a lower level of economic activity than the year before, and the future of civilization itself in the nations attacked would be in doubt.”

10 It is doubtful that either the United States or Russia would ever recover as viable nation-states.

CALCULATING REGIONAL WAR

There are grave dangers inherent not only in the thousands of nuclear weapons maintained by countries such as the United States and Russia but also in hundreds of weapons held by China, France, the United Kingdom, Israel, Pakistan, India, and North Korea. While these states regard their own nuclear weapons as safe, secure, and essential to security, each views the others’ arsenals with suspicion.

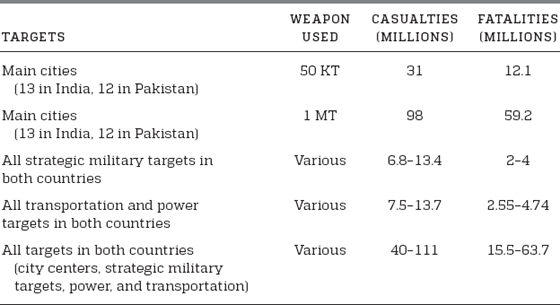

Existing regional nuclear tensions already pose serious risks. The decades-long conflict between India and Pakistan has made South Asia the region most likely to witness the first use of nuclear weapons since World War II. An active missile race is under way between the two nations even as India and China continue their rivalry. And though some progress toward détente has been made, with each side agreeing to notify the other before ballistic missile tests, for example, quick escalation in a crisis could put the entire subcontinent back on the edge of destruction. Each country has an estimated 60 to 110 nuclear weapons, deliverable via fighter-bomber aircraft or possibly by the growing arsenal of short and medium-range missiles each nation is building. Their use could be devastating.

Source: Robert T. Batcher, “The Consequences of an Indo-Pakistani Nuclear War,” International Studies Review 6, no. 4 (December 2004): 143–50.

South Asian urban populations are so dense that a 50-kiloton weapon would produce the same casualties that would require megaton-range weapons on North American or European cities. Robert Batcher with the U.S. State Department Office of Technology Assessment, notes:

Compared to North America, India and Pakistan have higher population densities with a higher proportion of their populations living in rural locations. The housing provides less protection against fallout, especially compared to housing in the U.S. Northeast, because it is light, often single-story and without basements. In the United States, basements can provide significant protection against fallout. During the Cold War, the United States anticipated 20 minutes or more of warning time for missiles flown from the Soviet Union. For India and Pakistan, little or no warning can be anticipated, especially for civilians. Fire fighting is limited in the region, which can lead to greater damage as a result of thermal effects. Moreover, medical facilities are also limited, and thus, there will be greater burn fatalities. These two countries have limited economic assets, which will hinder economic recovery.

11

In addition to immediate casualties, a limited nuclear exchange would have devastating long-term consequences.

CALCULATING NUCLEAR WINTER

In the early 1980s, scientists used models to estimate the climatic effect of a nuclear war. They calculated the effects of the dust raised in high-yield nuclear surface bursts and of the smoke from city and forest fires ignited by air-bursts of all yields. They found that “a global nuclear war could have a major impact on climate—manifested by significant surface darkening over many weeks, subfreezing land temperatures persisting for up to several months, large perturbations in global circulation patterns and dramatic changes in local weather and precipitation rates.”

12 Those phenomena are known as “nuclear winter.”

Since this theory was introduced, it has been repeatedly examined and reaffirmed. By the early 1990s, as tools to assess and quantify the effects of the production and injection of soot by large-scale fires, scientists were able to refine their conclusions. The prediction for the average land cooling beneath the smoke clouds was adjusted down a little bit, from the 10–25 degrees Celsius (50–77 degrees Fahrenheit) estimated in the 1980s to 10–20 degrees (50–68 degrees Fahrenheit). However, it was also found that interior land temperatures could decrease by up to 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), more than the 30–35 degrees (86–95 degrees Fahrenheit) estimated in the 1980s, “with subzero temperatures possible even in the summer.”

13In a

Science article in 1990, the authors summarized: “Should substantial urban areas or fuel stocks be exposed to nuclear ignition, severe environmental anomalies—possibly leading to more human casualties globally than the direct effects of nuclear war—would be not just a remote possibility, but a likely outcome.”

14 Carl Sagan and Richard Turco, two of the original scientists to develop the nuclear-winter analysis, concluded in 1993: “Especially through the destruction of global agriculture, nuclear winter might be considerably worse than the short-term blast, radiation, fire, and fallout of nuclear war. It would carry nuclear war to many nations that no one intended to attack, including the poorest and most vulnerable.”

15In 2007, members of the original group of nuclear winter scientists collectively performed a new comprehensive quantitative assessment using the latest computer and climate models.

16 They concluded that even a small-scale, regional nuclear war could kill as many people as died in all of World War II and seriously disrupt the global climate for a decade or more, harming nearly everyone on Earth. The scientists considered a nuclear exchange involving 100 bombs of the same size as that dropped on Hiroshima (15 kilotons) used on cities in the subtropics, and found that

smoke emissions of 100 low-yield urban explosions in a regional nuclear conflict would generate substantial global-scale climate anomalies, although not as large as the previous ‘nuclear winter’ scenarios for a full-scale war. However, indirect effect on surface land temperatures, precipitation rates and growing season lengths would be likely to degrade agricultural productivity to an extent that historically has led to famines in Africa, India and Japan after the 1784 Laki eruption or in the northeastern United States and Europe after the Tambora eruption of 1815. Climatic anomalies could persist for a decade or more because of smoke stabilization, far longer than in previous nuclear winter calculations or after volcanic eruptions.

17

The scientists concluded that the nuclear explosions and firestorms in modern cities would inject black carbon particles higher into the atmosphere than previously thought and higher than normal volcanic activity. Blocking the sun’s thermal energy, the smoke clouds would lower temperatures regionally and globally for several years, open up new holes in the ozone layer protecting the Earth from harmful radiation, reduce global precipitation by about 10 percent, and trigger massive crop failures. Overall, the global cooling from a regional nuclear war would be about twice as large as the global warming of the past century “and would lead to temperatures cooler than the pre-industrial Little Ice Age.”

18 A 2012 study by Dr. Ira Helfand of Physicians for Social Responsibility found that these conditions could lead to widespread famines that could kill a billion people.

19NUCLEAR BALANCE

Despite the horrific consequences of their use, many national leaders continue to covet nuclear weapons. Some see them as a stabilizing force, even in regional conflicts. There is some evidence to support this view. Relations between India and Pakistan, for example, have improved overall since their 1998 nuclear tests. Even the conflict in the Kargil region between the two nations that came to a boil in 1999 and again in 2002 (with more than one million troops mobilized on both sides of the border) ended in negotiations, not full-scale war. The Columbia University scholar Kenneth Waltz argues, “Kargil showed once again that deterrence does not firmly protect disputed areas but does limit the extent of the violence. Indian rear admiral Raja Menon put the larger point simply: ‘The Kargil crisis demonstrated that the subcontinental nuclear threshold probably lies territorially in the heartland of both countries, and not on the Kashmir cease-fire line.’”

20 It would be reaching too far to say that Kargil was South Asia’s Cuban Missile Crisis, but since the near-war, both nations have established hotlines and other confidence-building measures (such as notification of each side’s impending missile tests), exchanged cordial visits of state leaders, and opened transportation and communications links. War seems less likely now than at any point in the past.

This calm is deceiving. Just as in the Cold War standoff between the Soviet Union and the United States, the South Asian détente is fragile. A sudden crisis, such as a terrorist attack on the Indian parliament or the assassination of President Asif Ali Zardari of Pakistan, could plunge the two countries into confrontation. As noted above, it would not be thousands that would die, but millions. Michael Krepon of the Stimson Center, one of the leading American experts on the region and its nuclear dynamics, notes:

Despite or perhaps because of the inconclusive resolution of crises, some in Pakistan and India continue to believe that gains can be secured below the nuclear threshold. How might advantage be gained when the presence of nuclear weapons militates against decisive end games? … If the means chosen to pursue advantage in the next Indo-Pakistan crisis show signs of success, they are likely to prompt escalation, and escalation might not be easily controlled. If the primary alternative to an ambiguous outcome in the next crisis is a loss of face or a loss of territory, the prospective loser will seek to change the outcome.

21

Many share Krepon’s views both in and out of South Asia. The Indian scholar P. R. Chari, for example, further observes:

Since the effectiveness of these weapons depends ultimately on the willingness to use them in some situations, there is an issue of coherence of thought that has to be addressed here. Implicitly or explicitly an eventuality of actual use has to be a part of the possible alternative scenarios that must be contemplated, if some benefit is to be obtained from the possession and deployment of nuclear weapons. To hold the belief that nuclear weapons are useful but must never be used lacks cogency.

22

A new and quickly escalating crisis over Taiwan or disputed territories in the South China Sea is another possible scenario in which nuclear weapons could be used, not accidentally as with any potential U.S.-Russian exchange, but as a result of miscalculation. Neither the United States nor China is eager to engage in a military confrontation over Taiwan’s status or ownership of remote islands. Both sides believe they could effectively manage such a crisis. But crises work in mysterious ways—political leaders are not always able to manipulate events as they think they can, and events can escalate quickly. A Sino-U.S. nuclear exchange may not happen even in the case of such confrontations, but the possibility should not be ignored.

The likelihood of use depends greatly on the perceived utility of nuclear weapons. This, in turn, is greatly influenced by the policies and attitudes of the existing nuclear-weapon states. Advocacy by some in the United States of new battlefield uses for nuclear weapons (for example, in preemptive strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities) and for programs for new nuclear weapon designs could lead to fresh nuclear tests and possibly lower the nuclear threshold, i.e., the willingness of leaders to use nuclear weapons. The five nuclear-weapon states recognized by the Non-Proliferation Treaty have not tested since the signing of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1996, and until North Korea’s October 2006 test, no state had tested since India and Pakistan did so in May 1998. Despite North Korea’s tests, no other nation has broken this informal global test moratorium.

If the United States again tested nuclear weapons, political, military, and bureaucratic forces in several other countries would undoubtedly pressure their governments to follow suit. Indian scientists, for example, are known to be unhappy with the inconclusive results of their 1998 tests. Indian governments now resist their insistent demands for new tests for fear of the damage they would do to India’s international image. It is a compelling example of the power of international norms. New U.S. tests, however, would collapse that norm and trigger tests by India then perhaps China and other nations. The nuclear test ban treaty, an agreement widely regarded as a pillar of the nonproliferation regime, would crumble, possibly bringing down the entire regime.

All of these scenarios highlight the need for nuclear-weapons countries to decrease their reliance on nuclear arms. While the United States has reduced its arsenal to the lowest levels since the 1950s, it has received little credit for these cuts because the reductions were conducted in isolation from a real commitment to disarmament. To demonstrate a serious intent to commit to disarmament, the United States, Russia, and all nuclear-weapons states need to return to the original purpose of the NPT bargain—the elimination of nuclear weapons. The failure of nuclear-weapons states to accept their end of the bargain under Article VI of the NPT has undermined every other aspect of the nonproliferation agenda.

Universal Compliance, a 2005 study concluded by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, reaffirmed this premise:

The nuclear-weapon states must show that tougher nonproliferation rules not only benefit the powerful but constrain them as well. Nonproliferation is a set of bargains whose fairness must be self-evident if the majority of countries is to support their enforcement.… The only way to achieve this is to enforce compliance universally, not selectively, including the obligations the nuclear states have taken on themselves.… The core bargain of the NPT, and of global nonproliferation politics, can neither be ignored nor wished away. It underpins the international security system and shapes the expectations of citizens and leaders around the world.

23

While nuclear weapons are more highly valued by national officials than chemical or biological weapons ever were, that does not mean they are a permanent part of national identity. Steps to reduce the nuclear dangers and move towards the eventual elimination of these weapons are explored in the final chapter. But before that, we need to put together a few more pieces of the nuclear puzzle.

Immediate Deaths from Blast and Firestorms in Eight U.S. Cities, Submarine Attack

Immediate Deaths from Blast and Firestorms in Eight U.S. Cities, Submarine Attack