1 Background: The Role of Evidence and Procedural Laws in Sexual Assault Trials

- (i)

exclusionary rules of evidence;

- (ii)

a requirement for corroboration in relation to the evidence of accomplices, sexual assault complainants and children;

- (iii)

cross-examination of witnesses; and

- (iv)

judicial warnings.

The accepted wisdom about the rules of evidence and procedure that apply in a criminal trial is that they impose a structure which ensures fairness for both the defence and the prosecution. However, historically, the prosecution was often prevented from fully explaining the context in which an alleged sexual assault occurred through legal restrictions preventing the admission of similar fact or propensity evidence against the accused (Cossins, 2011a, 2013a) and the general, historical trend to hold separate rather than joint trials where more two or more complainants made allegations against the same defendant (Cossins, 2011b).

Instead, the criminal law developed various rules and procedures to highlight the assumed unreliability of the evidence of sexual assault complainants, rather than providing evidence about a defendant’s propensities.

Historically, children’s evidence faced stringent competency rules in some jurisdictions before reforms were introduced.1 Still, today, trials may not proceed when the complainant has an intellectual disability,2 even though intellectually disabled children are at greater risk of sexual abuse compared to all other groups (Hershkowitz, Lamb, & Horowitz, 2007; Jones et al., 2012; Wissink, van Vugt, Moonen, Stams, & Hendriks, 2015).

For more than a century, both women’s and children’s evidence was subject to judicial warnings about the quality of their evidence so that, for example, in Australia, a sexual assault trial may contain up to eleven warnings in addition to standard judicial directions about the burden of proof and the role of the jury.3 This means that the criminal trial process in sexual assault cases has been peculiarly weighted against complainants whose evidence continues to be filtered through the lens of rape myths and misconceptions, as discussed in the previous chapters.

The sexual assault trial represents a gendered structure of power relations that emerged, historically, as a result of the belief that women’s and girls’ evidence about being sexually assaulted was unreliable unless corroborated (either by eyewitnesses, immediate complaint and/or physical evidence of injury). These beliefs were documented and repeated over hundreds of years by legal commentators such as Bracton (1268/1968) and Blackstone (1765–1769).

in order to prevent malicious accusations, … the woman should immediately after, ‘dum recens fuerit maleficium’ [‘while the injury is recent’], go to the next town, and there make discovery to some credible persons of the injury she has suffered; and afterwards should acquaint the high constable of the hundred, the coroners, and the sheriff with the outrage. … At present there is no time of limitation fixed: … but the jury will rarely give credit to a stale complaint.

This ‘hue and cry’ requirement was unlikely to have been a practice that traumatised women and girls could readily engage in, particularly if it required revealing their loss of chastity.

Evidence about the veracity of a sexual assault complaint is not interpreted by lawyers or jurors objectively, but subjectively based on pre-existing cultural beliefs. Indeed, the specific substantive law and rules of evidence and procedure that apply in a sexual assault trial mirror cultural forms of the moral regulation of women and girls (Cossins, 2015), and encourage particular types of jury reasoning about women’s and children’s tendency to lie about being sexual assaulted, their promiscuity, and/or desires for revenge.

For many victims, the sexual assault trial is an ordeal, sometimes described as bad or worse than the original abuse (Cossins, 2019), a place where the complainant’s behaviour is on trial. There are limited ways of preventing a sexual assault trial from turning into a character assassination of the complainant by defence counsel, while complainants, with no legal representation, have no control over the trial process. The authority of the state justifies a complainant’s re-traumatisation with a variety of defence allegations about her character and past still permitted, including drug and alcohol use, psychiatric history and past criminal offences.

Thus, there is a huge risk for complainants who choose to participate in a sexual assault trial—re-traumatisation is a documented phenomenon, as discussed in Chapter 11, and one reason that women and children do not proceed with their complaints.5

We also have no methods for vetting jurors to discover the rape myths (or heuristics) they adhere to while juries do not give reasons for their decisions in criminal trials. Thus, jurors are free to use heuristics to decide the key legal issues in an adult sexual assault trial: did she consent and what was his state of mind? Without eyewitnesses and other supporting evidence, the defendant’s denial will generally be measured by reference to the complainant’s behaviour.

As discussed in Chapter 5, numerous studies reveal the extent to which laypeople endorse the misconceptions associated with RMA and the fact that the higher an individual’s level of RMA, the more likely s/he will blame the victim, and the less likely s/he will perceive the victim to be credible and the defendant to be culpable (Stewart & Jacquin, 2010). In fact, there is a positive correlation between relatively high levels of RMA and a tendency to acquit in sexual assault trials (Dinos, Burrowes, Hammond, & Cunliffe, 2015).

- (i)

burden of proof on the prosecution;

- (ii)

criminal standard of proof (beyond reasonable doubt) which is higher than the civil standard of proof (balance of probabilities);

- (iii)

defendant’s right to remain silent; and

- (iv)

lack of a burden on the defendant to mount a case or prove his/her innocence.

- (i)

in a CSA trial, the commission of the alleged sexual conduct by the defendant;

- (ii)

in an adult sexual assault trial, typically lack of consent and knowledge of lack of consent on the part of the defendant.

Very early in a criminal trial, the jury is faced with competing hypotheses which encourages jurors to engage in a hypothesis-testing process (Carlson & Russo, 2001) whereby they determine the likelihood of the competing prosecution and defence hypotheses. Studies show that defence addresses to the jury can influence verdicts (Haegerich & Bottoms, 2000) by including empathy-inducing statements about the defendant such as asking the jury to put themselves in his or her shoes. When a fact-finder favours a particular outcome during the trial before delivering their final verdict, this early preference influences their interpretation of subsequent evidence. This process is known as pre-decisional distortion (Carlson & Russo, 2001; DeKay, 2015) and amounts to ‘a form of self-fulfilling prophecy in which the decision-maker is especially likely to choose the initially preferred option’ (DeKay, 2015: 405). Indeed, in Chapter 2, a review of the literature showed that juror verdicts before deliberation had a greater tendency to prevail after deliberation.

The effect of stereotypes in criminal trials has been examined by Haegerich, Salerno, and Bottoms (2013), specifically the effect of juvenile stereotypes on pre- and post-deliberation judgements in a mock trial in which the defendant was a juvenile offender. Jurors’ adherence to two stereotypes (‘Wayward Youth’ and ‘Super-predator’) were measured and, in some mock trials, were encouraged by attorneys’ arguments. The authors found that that the more jurors adhered to the ‘Super-predator’ stereotype, the more likely they were to vote guilty, although the effects of jurors’ pre-existing biases were somewhat minimised after jury deliberation.

were given the prosecuting attorney’s opening statements and closing arguments with an added paragraph that emphasized the problem of ‘Superpredators’ who commit serious crimes, informing jurors that the defendant in this case is a perfect example of a ‘Superpredator’. (Haegerich et al., 2013: 86)

A similar paragraph emphasised the problem of Wayward Youths in the second stereotype condition.

It was only in the ‘Super-predator’ condition that jurors were more likely to find the defendant guilty (100%) compared to jurors in the control and ‘Wayward Youth’ trials. Jurors’ activated biases (compared to their pre-existing biases) were maximised after jury deliberation, especially in robbery cases. In addition, the effect of counsels’ activating and biasing statements was ‘significant regardless of jurors’ own pre-existing beliefs about juvenile offenders’ (Haegerich et al., 2013: 90).

The question then is, ‘[w]hy would preexisting stereotypes be minimized after deliberation, while activated stereotypes [were] maximized after deliberation?’ (Haegerich et al., 2013: 91). The authors speculate that jurors controlled their pre-existing biases ‘due to normative concerns about self-presenting as a biased person’ or due to correction by other jurors, although ‘if most jurors … share beliefs about a defendant before deliberation, then that jury will be more likely to render a verdict in line with those beliefs after deliberation’ (Haegerich et al., 2013: 91).

By contrast, the expression of activated biases may be less likely to be controlled where those biases come from authoritative sources (such as trial counsel) and where they are shared by the group, something that would become apparent during deliberation. As well, since all jurors will have heard the activated biases during the trial, this ‘might result in most members of the jury focusing on stereotype-consistent information’ as relevant information during deliberation (Haegerich et al., 2013: 91). Thus, jury deliberation can both maximise or minimise biases.

Even though jurors in the study were told that defence and prosecution opening/closing addresses did not amount to evidence, the findings show that ‘the manner in which case material is presented’ in a trial can influence verdicts, ‘putting the fairness of the legal system in jeopardy’ (Haegerich et al., 2013: 89). Thus, controlling the content of counsels’ ‘biasing statements about the defendant during opening and closing arguments might be more important in decreasing juror bias’ (Haegerich et al, 2013: 90) than other strategies.

inform jurors about the potential bias that attorneys’ statements may have on their decision making, even without their awareness, and that they can attempt to resist such biases by being more cognitively aware, critically evaluating the evidence and the conclusions that the attorneys assert about what happened.

- (i)

What are the implications of the above research for the sexual assault trial?

- (ii)

Would judicial instructions solve the endemic problem of the effect of RMA and misconceptions on jury decision-making? (see Chapter 12).

2 Activation Statements in Sexual Assault Trials

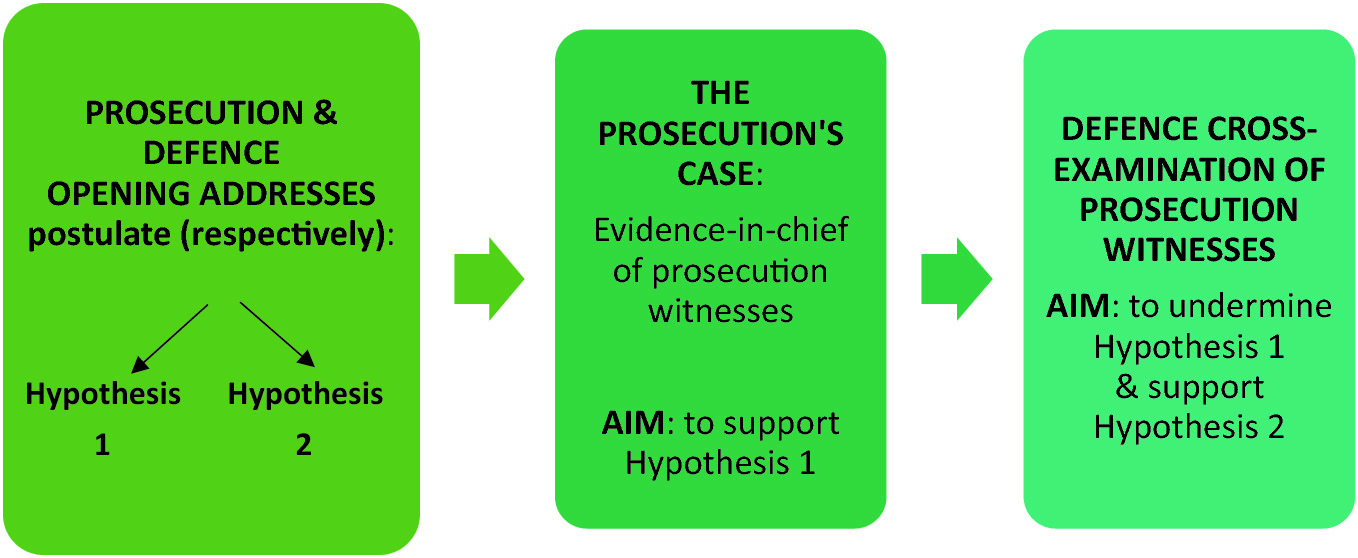

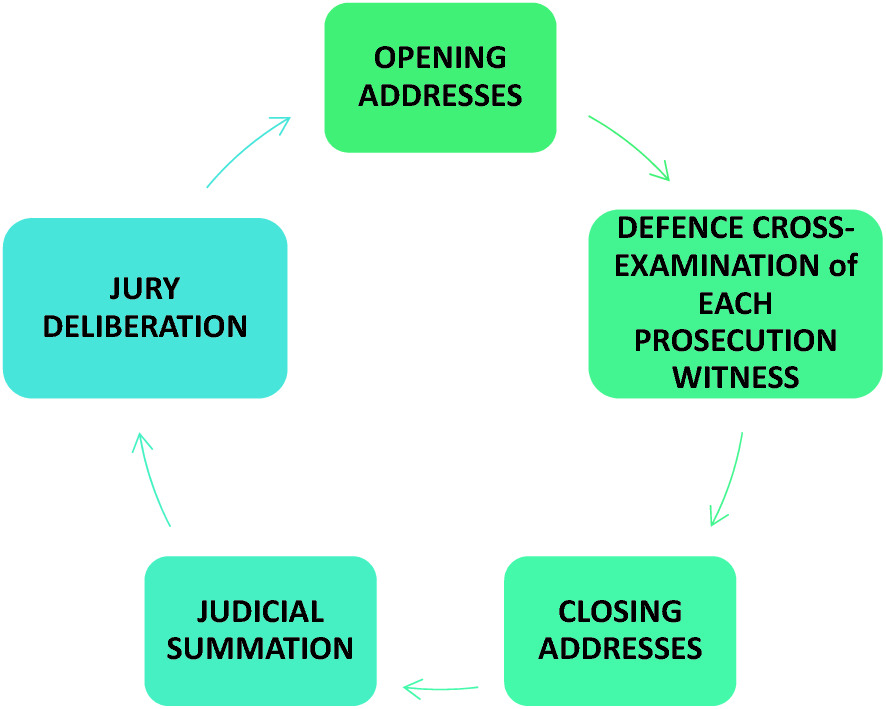

The parts of a criminal trial that encourage hypothesis-testing by the jury

In a CSA trial, where consent is usually not a fact in issue, the prosecution’s hypothesis is that the defendant committed the alleged sexual conduct.

From the outset, however, Hypothesis 1 is under attack from the defence when the defence encourages any pre-existing juror biases and the use of heuristic reasoning by activating particular gender, victim and/or offence stereotypes (Hypothesis 2 in Fig. 1). By contrast, Hypothesis 2 remains untested unless the defence opens a case since the defendant is not required to mount a defence or give evidence. Thus, the defence does not have to provide any evidence to support Hypothesis 2 and, instead, relies on the general prevalence of RMA and misconceptions about children among laypeople called up for jury duty.

The acceptance of a defence hypothesis based on myths, prejudice and misconceptions constitutes the implicit acceptance by the criminal justice system of the relevance of such speculation in a sexual assault trial. Thus, the defence is not required to satisfy an evidential burden when relying on particular gender, victim and/or offence stereotypes in their cross-examination of the complainant which she must refute because of the burden on her to prove her lack of consent (or to prove that the sexual assault occurred), as the prosecution’s chief witness.

Since the defence narrative in a sexual assault trial is driven by defence hypotheses that undermine a complainant’s credibility and since the main vehicle for this narrative is cross-examination, there is little or no opportunity for the prosecution to attack the defence narrative. Even re-examination by a prosecutor is designed to restore a witness’s credibility rather than disprove any defence narrative about the complainant’s moral unworthiness.

If the defence narrative is bolstered by judicial comments and warnings about delayed complaint and lack of corroboration, which also pertain to a complainant’s credibility, this can potentially reinforce activated stereotypes and any doubts held by jurors about the defendant’s guilt.

For example, in a study that tested the impact of pro- and anti-rape myth bias statements on the individual verdicts of 90 UK university students, participants who received pro-rape myth guidance ‘were significantly more likely than those receiving anti-rape myth guidance to be confident that the defendant was innocent’, regardless of mock jurors’ levels of RMA (Gray, 2006: 78). These results suggest that even jurors with low levels of RMA can be influenced by pro-rape myth statements by court personnel, although rape myth supportive statements may be more influential on men than women (Gray, 2006).

Sites of activation: heuristics within a criminal trial

2.1 Prosecution and Defence Opening Addresses

Before any evidence is admitted, adversarial criminal trials permit counsel to address the jury. The purpose of the prosecution’s opening address is to outline the case for the prosecution, that is, to provide a summary of the charges against the defendant, the evidence to be presented and witnesses to be called in order to support the prosecution’s hypothesis—that the defendant is guilty of the charges in question.

The purpose of defence counsel’s opening address is to undermine the prosecution’s hypothesis by denying guilt and, in a sexual assault trial, proposing an alternative explanation for the events leading up to the charges, such as revenge by the complainant or a desire for victims’ compensation. Thus, the defence opening address encourages jurors to engage in heuristic processing by using heuristic cues (or short cuts) to filter the evidence presented in the prosecution’s case, in particular the complainant’s testimony.

Because opening addresses do not amount to evidence, jurors are presented with opposing hypotheses before any actual evidence has been admitted. Thus, opening addresses may discourage jurors from interpreting the trial evidence in order to devise their own hypotheses since the interpretative process has been done for them. While jurors are not prevented from devising alternative hypotheses, to do so requires them to put the prosecution and defence hypotheses to one side and engage with the evidence in a deeper way, something that not all jurors will be capable of, as discussed in Chapter 5, in relation to the dual processing model of jury decision-making.

Because the burden of proving the charge(s) against the defendant lies with the prosecution, the prosecution’s case follows the opening addresses. The prosecution opens its case by calling witnesses to give oral evidence, and/or by adducing other evidence (such as medical and forensic evidence, exhibits and/or CCTV footage) in order to prove that the defendant is guilty of the charge(s) beyond reasonable doubt. In other words, the aim of all the evidence adduced by the prosecution is to support Hypothesis 1 in Fig. 1.

During the prosecution case, the aim of defence cross-examination of prosecution witnesses is to undermine Hypothesis 1 by styles of questioning that create doubt about the credibility of prosecution witnesses, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. As noted above, there is no balancing process which allows the prosecution to test Hypothesis 2 unless the defence opens a case and calls witnesses to give evidence. Thus, in a sexual assault trial, jurors are faced with determining the plausibility of the complainant’s version of events compared with the defence’s hypothesis which, by the end of the trial, may not have been tested. As well, we know that presentation order of evidence affects decision-making, that is, the most recent evidence or information can have the strongest impact (Dahl, Brimacombe, & Lindsay, 2009; Lagnado and Harvey, 2008), such as the defence closing address which closes the trial.

The way that criminal trials are conducted, with a step-by-step process of adducing each item of evidence and calling each witness, also encourages jurors to reach premature conclusions (Carlson & Russo, 2001: 91). Carlson and Russo (2001: 91) found that preventative instructions did not stop mock jurors and actual jurors from engaging in pre-decisional distortion, that is, ‘jurors’ biased interpretation of new evidence to support whichever verdict is tentatively favoured as a trial progresses’. Distortion of evidence can also occur as a result of jurors’ prior beliefs or misconceptions about crime, victims and defendants. But even if jurors hold no prior beliefs or are able to put them aside, ‘jurors naturally establish a tentative favourite side (or leading verdict) early in the trial and then evaluate new evidence as overly supportive of that currently leading verdict’ (Carlson & Russo, 2001: 92).

Models of juror decision-making, such as the widely cited story model (Pennington & Hastie, 1986, 1992), predicts that jurors construct sometimes competing narratives of the events leading up to the charges in question from their interpretation of the evidence, their assessment of witness credibility, their own knowledge of the world and human behaviour. Eventually, according to Pennington and Hastie (1986), one story will emerge that makes the most sense based on coverage, coherence and uniqueness.

2.2 Jurors’ Narrative Framework

Most criminal trials involve conflicting accounts of events as presented by the prosecution and the defence, with different witnesses and exhibits ‘convey[ing] pieces of a historical puzzle in a jumbled temporal sequence’ and inevitable gaps in the chronology of events (Pennington & Hastie, 1988: 521). Jurors reconcile these accounts and bridge the gaps by constructing a narrative framework that provides a commonsensical story of events and actions (Pennington & Hastie, 1992) which may contain imaginary elements based on jurors’ life experiences and expectations (Ellison & Munro, 2009a, 2009b).

The descriptive, ‘story model’ of jury deliberation has been widely accepted in the literature as a way of explaining jury deliberation and the final verdicts (Blume, Johnson, & Paavola, 2007; Devine, 2012; Huntley & Costanzo, 2003). It has supplanted various mathematical models of jury decision-making due to the latter’s assumptions about jurors weighing and adding all the evidence in a machine-like way, rather than the evolution of possible stories that fit with the evidence that has been accepted by jurors (Devine, 2012).

support[ed] Pennington and Hastie’s (1992) assertions that prior to selecting a verdict, jurors appear to assess competing witness accounts in terms of a subscribed set of certainty principles, in order to determine which story they deem most believable, before voting accordingly.

In fact, while the elements of the story model (coverage, coherence, completeness, plausibility and uniqueness, all of which are explained below) ‘are clearly important determinants upon individual decision formation …, these assessments appear to be influenced in themselves by preconceived attitudes jurors hold’ (ibid., 33).

Through the story model, jurors construct a causal explanation of events from evidence presented at trial and their own ‘related world knowledge’ (Pennington & Hastie, 1988: 522). Because the story model assumes that jurors actively process trial information, jurors are believed to sift through the evidence, ‘focusing on some elements and discarding others’ (Devine, 2012: 27) while simultaneously making inferences in order to create a chain of events or actions that are causally related to one another to create a plausible story (Pennington & Hastie, 1988: 522).

[e]xpectations about the kinds of information necessary to make a story tell the juror when important pieces of the explanation structure are missing and when inferences must be made. (Pennington & Hastie, 1988: 522)

undifferentiated automatons who make decisions based on a rational, standardized processing of the evidence. Instead, jurors’ stories are viewed as heavily influenced by their life experiences and perceptions at trial. (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 111)

it is not just the coherence of one story that affects decisions … but rather it is the strength of one story compared with the alternative that is important. (Pennington & Hastie, 1988: 530)

Nonetheless, the agreed story may include fictional elements because jurors’ inferences to fill gaps in the evidence may not accord with the facts of the case but, instead, accord with their pre-existing cognitive schema concerning human behaviour. In a context of competing and conflicting accounts, subjectivity is an unavoidable part of jurors’ explanation-driven interpretation of trial evidence. Although jurors hear and see the same evidence, their narratives differ based on their own subjective frameworks. In other words, they may focus on evidence that is consistent with their life experiences and ignore or reject evidence that is not (Carlson & Russo, 2001). Thus, jurors do not merely interpret trial testimony and other evidence based on the directions given to them by the trial judge, they actively process that information to ‘fit’ with their own experiences of, and beliefs about, human behaviour. This will involve assessments of witness credibility (such as, ‘she looked like she was lying’, ‘he looked like an honest man’), as well as characteristics of the defendant and complainant, such as their race and gender.

all models of jury decision making incorporate the well-established strength-in-numbers effect associated with faction size …: initial majorities, especially strong ones, tend to prevail. (Devine, 2012: 21, 39)

Based on the empirical evidence (Pennington & Hastie, 1986, 1988, 1992; Devine, 2012: 29, 39) concludes that the story model ‘has emerged as the leading model in the juror decision-making literature’ since it ‘provides a simple, powerful and compelling depiction of juror decision making’.

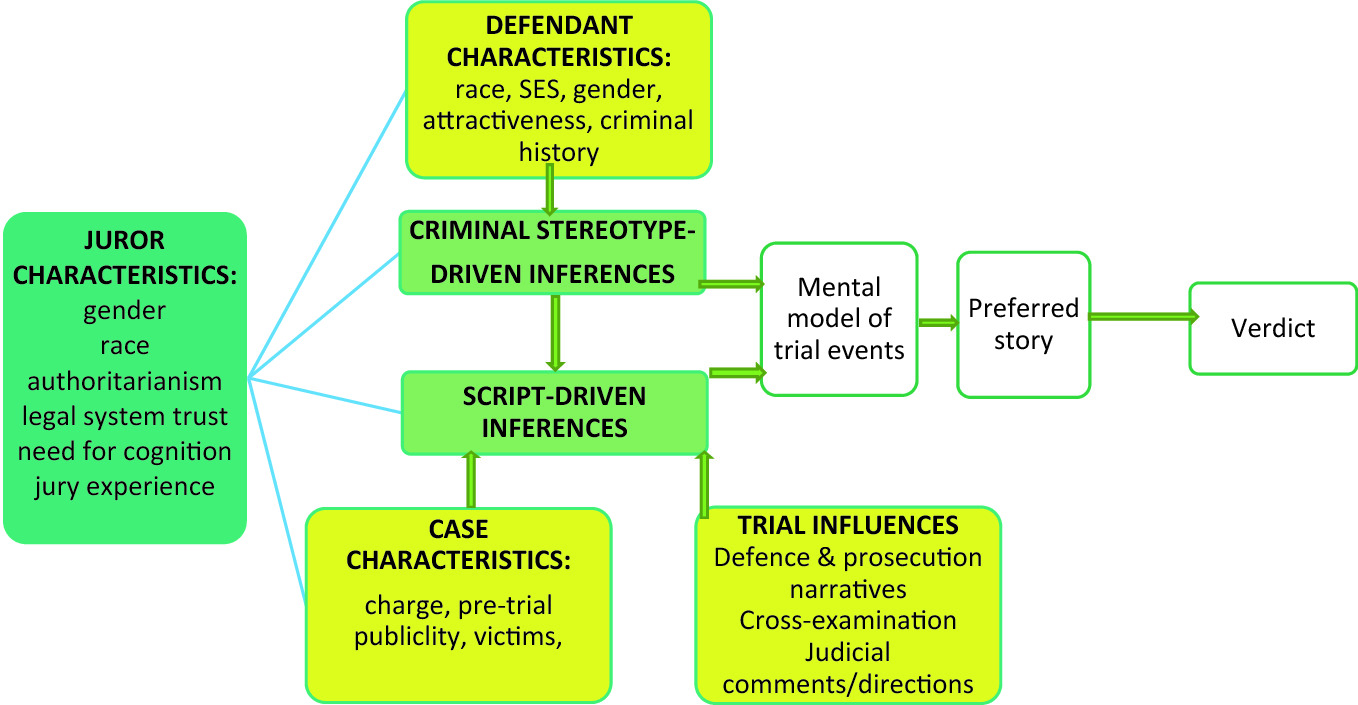

- (i)

juror race, gender, socioeconomic status, trust in the legal system and need for cognition; and

- (ii)

defendant race, socioeconomic status, prior criminal record, physical attractiveness and courtroom demeanor.

the director’s cut model says that jurors’ initial mental representations of trial-related events are determined by juror and defendant characteristics along with any information acquired before the trial via the media, the nature of the charges, and the attorneys’ opening statements.

the basis for formulating one or more stories, which are then translated into mental models for evaluation. How stories fare when tested via mental simulation then has direct implications for a juror’s preferred verdict. (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 111)

‘Director’s cut’ model linking juror and defendant characteristics to juror decisions (Adapted from Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 112; with additions by author)

Out of this interaction, jurors construct an ‘initial mental representation of the trial’, although criminal stereotypes and scripts will vary depending on the criminal charge and victim characteristics. Stereotypes are defined as ‘person-related categories consisting of a central label and associated behavioral attributes’, while scripts are defined as ‘sets of related events that are understood to occur in a causal sequence’ (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 111).

From the mental model of trial events emerges one or more stories. Arguably, a better description is the term, ‘narrative’, since the story model and director’s cut models rely on a narration of events, which may or may not be accurate, based on ‘inferences about what is true’, and what is ‘stored in memory and made accessible via the activation of jurors’ stereotypes and scripts’ (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 111), that is, heuristic cues.

Although Devine and Caughlin (2014) consider that ‘jurors’ stereotypes and scripts are a function of life experiences’, stereotypes may be adhered to as a result of ‘cultural knowledge’, that is, ways of understanding certain people and situations based on media sources (such as TV crime shows) as well as gossip and rumour. Rape myths fall into this category. Jurors may have a number of beliefs about rape victims which amount to a stereotype even though jurors may have had no experience of, or contact with, a rape victim.

Under the director’s cut model, rape myths would amount to a standard script involving adherence to a particular victim/gender stereotype (real victim vs unreal victim) as well as a particular criminal stereotype (such as stranger rape) which would lead jurors to process the trial evidence to form either a pro-conviction or pro-acquittal narrative depending on the extent to which the complainant and defendant matched the script and stereotypes.

In a rape trial, we know that men exhibit higher levels of RMA than women so that male jurors would be more likely to be ‘attitudinally predisposed’ (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 111) to favour the narrative of events proposed by the defence while female jurors would be more likely to be ‘attitudinally predisposed’ to favour the narrative of events proposed by the prosecution. Similarly, adherence to a particular criminal stereotype (e.g. that rape is a violent crime) may predispose a juror to interpret the trial evidence as either fitting or not fitting that stereotype. As well, particular defendant characteristics may predispose a juror to view the defendant as a ‘typical’ criminal, thus triggering a particular criminal stereotype as portrayed in Fig. 3 above. For example, a high SES defendant on trial for sexual assault may be less likely to trigger a criminal stereotype but more likely to trigger a negative victim stereotype, thus leading jurors to construct a narrative in which the defendant has been wrongly accused.

- (i)

‘the focal characteristics of defendants and jurors … [set out in Fig. 3] have weak to modest overall relationships with juror predeliberation judgments of criminal culpability’;

- (ii)

‘Most of these relationships are likely moderated by other variables and will accordingly vary across trial contexts’;

- (iii)

‘The nature of the participants used in research does not appear to have a sizable or consistent effect on estimates of the relationship between participant characteristics and guilt judgments’;

- (iv)

‘The relationship between two juror characteristics (authoritarianism and gender) and judgments of defendant culpability likely varies by case type’. (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 119–120)

For example, juror education level, prior experience as a juror, defendant physical attractiveness, defendant gender and defendant race produced little or no effect on case outcomes, although there may be case types in which one or more of these characteristics does produce ‘a stronger relationship with guilt judgments’ (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 120). However, the effect of juror gender is much more significant in sexual assault trials, particularly those involving children, compared to other criminal cases where female jurors are significantly more likely to convict than male jurors.

juror authoritarianism was a better predictor of guilt judgments for cases involving general homicide … and the death penalty … than adult sexual assault cases …. This may be because sexual crimes rarely involve third-party eyewitnesses and often present jurors with a difficult choice regarding the issue of consent. (Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 123)

Research on the influence of misconceptions and extra-legal biases in sexual assault trials confirms the existence of cognitive schemas that are used to categorise the expected behaviours of women and children before, during and after a sexual assault as discussed in Chapter 5. Based on the above findings regarding juror characteristics, as well as findings from RMA studies and other related studies summarised in Chapter 5, how might the conceptual model look for the sexual assault trial?

Adaptation of the ‘Director’s cut’ model linking juror, defendant and victim characteristics to juror decisions in sexual assault trials (Adapted from Devine & Caughlin, 2014: 112)

2.3 The Story Model and Pre-decisional Distortion

- (i)

Mock jurors (university students) engaged in pre-decisional distortion when delivering individual verdicts in both civil and criminal simulated lawsuits, ‘despite multiple instructions to suspend judgment until all the evidence had been presented’;

- (ii)

Jurors (average age: 40–45 years) who had completed jury orientation at a Wisconsin courthouse also engaged in pre-decisional distortion but were more biased than the younger mock students;

- (iii)

Actual jurors’ judgements showed twice as much distortion, greater reliance on their prior beliefs and greater confidence in their favoured verdicts, compared to the mock jurors, with jurors’ prior beliefs being a reliable predictor for their verdicts;

- (iv)

The higher confidence level of jurors was due, in part, to their tendency to use their prior beliefs early in the decision-making process whereas the younger mock jurors successfully followed instructions to ignore their prior beliefs.

Because Carlson and Russo (2001) used written affidavits rather than actual or videotaped testimony and excluded judicial directions and jury deliberation, it is possible that a real trial with complete testimony, cross-examination, judicial instructions and jury deliberation would amplify the effects of pre-decisional distortion because, as discussed above, trials are structured around competing narratives from the prosecution and the defence. In fact, trial processes encourage jurors to attach themselves to one side or the other through the processes of evidence-in-chief and adversarial cross-examination, competing experts, opening and closing addresses of counsel, and, sometimes, presentation of a defence case. As well, jurors’ attachment to one hypothesis over another may also include variables such as defendant SES, the personal appeal of competing lawyers (Gunnell & Ceci, 2010) and/or the behaviour of the complainant in the witness box which are impossible to control for.

Jurors seek to formulate a coherent account of the evidence presented, one that is coherent with their prior beliefs, counsels’ opening arguments, the judge’s instructions to the jury, and so on.

Although individual beliefs which favour one side over the other may be counteracted by the deliberation process, the liberation hypothesis, discussed in Chapter 2, asserts that where the prosecution evidence is weak or ambiguous, as in sexual assault cases, jurors are susceptible to non-evidentiary influences that is, extra-legal factors, such as race, ethnicity, gender and RMA beliefs.

Jurors need only harmonize new evidence with the currently leading verdict by distorting the evidence to conform to the emerging story that supports the leading story.

Depending on the leading verdict, that story is also likely to mirror the narrative proposed by either the prosecution or the defence. Thus, ‘at any time during a trial, there is a dominant story, or rather a leading verdict and a corresponding story, that best accounts for the evidence’ which is based on jurors’ prior beliefs (or heuristics) in order to attain the ‘goal of coherence’ (Carlson & Russo, 2001: 100), with these beliefs driving the interpretation of each new item of evidence. In other words, pre-decisional distortion of the evidence is used by jurors to attain coherence with prior beliefs which explains the influence of rape myths and misconceptions on credibility assessments of complainants and verdicts in sexual assault trials.

you represent a cross section of the community—a cross section of its wisdom and its sense of justice. You are expected to use your individual qualities of reasoning; your experience; and your understanding of people and human affairs. In particular, … you are expected to use your common sense and your ability to judge your fellow citizens, so that you bring to the jury room … your own experience of human affairs, which must necessarily be as varied as the twelve of you. (Judicial Commission, 2017: [7-020])

- (1)

Of untruthfulness:

- (a)

Delay in making a complaint.

- (b)

Complaint made for the first time when giving evidence.

- (c)

Inconsistent accounts given by the complainant.

- (d)

Lack of emotion/distress when giving evidence.

- (a)

- (2)

Of truthfulness:

- (a)

A consistent account given by the complainant.

- (b)

Emotion/distress when giving evidence.

- (a)

- (3)

Of consent and/or belief in consent:

- (a)

Clothing worn by the complainant said to be revealing or provocative.

- (b)

Intoxication (drink and/or drugs) on the part of the complainant while in the company of others.

- (c)

Previous knowledge of, or friendship/sexual relationship between, the complainant and the defendant. In this regard it may be necessary to alert the jury to the distinction between submission and consent.

- (d)

Some consensual sexual activity on the occasion of the alleged offence.

- (e)

Lack of any use or threat of force, physical struggle and/or signs of injury. Again it may be necessary to alert the jury to the distinction between submission and consent.

- (a)

It would be understandable if some of you came to this trial with assumptions about rape. You may have ideas about what kind of person is a victim of rape or what kind of person is a rapist. You may also have ideas about what a person will do or say when they are raped. But it is important that you dismiss these ideas when you decide this case. From experience we know that there is no typical rape, typical rapist or typical person that is raped. Rape can take place in almost any circumstance. It can happen between all different kinds of people. And people who are raped react in a variety of different ways. So you must put aside any assumptions you have about rape. All of you on this jury must make your judgement based only on the evidence you hear from the witnesses and the law as I explain that to you. (Judicial College, 2018: 20–24)

However, the phenomenon of pre-decisional distortion as illustrated in the ‘Director’s cut’ model (Fig. 3) which links juror and defendant characteristics to juror decisions as well as my adaptation of the ‘Director’s cut’ model (Fig. 4) which links juror, defendant and victim characteristics to juror decisions in sexual assault trials suggests that judicial instructions will have limited impact. In other words, judicial instructions must compete with juror characteristics that manifest as a pro-defence bias, as well as jurors’ interpretations of the complainant and her background, the defendant’s characteristics (e.g. low vs high SES, prior or no criminal history) and case characteristics (stranger rape vs acquaintance rape), including prosecution and defence narratives, all of which will be used to create a coherent narrative from jurors’ points of view. Judicial instructions at the end of a trial about not making assumptions about rape victims will be too late since ‘[o]nce jurors have distorted the evidence, it may be impossible for them to reconstruct an unbiased version of that same evidence’ (Carlson & Russo, 2001: 100).

In a sexual assault trial, an untested defence narrative will also reinforce pre-decisional distortion along with the case, victim and defendant characteristics that influence jurors to select the most coherent story. While the prosecution narrative, which is based on the evidence presented in the trial, is always tested by the defence, the defence narrative is often composed of myth and speculation. For example, a prosecution narrative such as ‘the defendant took advantage of the complainant, plied her with alcohol and despite being told to leave her apartment, he climbed into her bed and had intercourse with her against her will’, will be supported by the complainant’s evidence and any other relevant evidence.

By contrast, the opposing defence narrative, such as ‘the complainant invited the defendant back to her home where they drank a bottle of wine together and she invited him to stay the night’ will remain untested unless the defence calls witnesses and other evidence to support the narrative. While jurors may be instructed that prosecution and defence opening/closing addresses do not amount to evidence, they provide the context or framework in which the trial evidence is interpreted and represent the starting point for any pre-decisional distortion.

Carlson and Russo’s (2001: 98) study found that, compared to mock jurors, actual jurors’ prior beliefs ‘creat[ed] differential receptivity to the evidence’—those who favoured one side over the other interpreted each affidavit according to their favoured side while their favouritism was driven by their prior beliefs. Thus, if a juror uses experiential reasoning (Gunnell & Ceci, 2010) by relying on heuristics in his/her decision-making, such as, ‘a woman who invites a man back to her home is asking for trouble’, then the narrative that coheres with these heuristics is likely to dominate.

This raises the question: what is the impact of prior beliefs, including RMA, in creating pre-decisional distortion in a sexual assault trial? No study has examined this question, or whether or not jury deliberation rectifies or reinforces pre-decisional distortion in a sexual assault trial. Given the commonality of rape myths and misconceptions, if a majority of jurors adhere to them, deliberation is likely to have a reinforcing effect, while hung juries may represent the situation where groups of jurors adhere to opposing beliefs.

emphasizes ‘vibes’, emotions, and stereotypical thinking from past events … [and] is also associated with solving problems that rely on life lessons and experience that elude articulation and logical analysis … and is particularly prone to logical shortcuts or heuristics … . The rational [systematic processing model] …, on the other hand, is intentional and effortful. It is logic-driven; it is active, conscious, and requires justification via evidence … and it makes possible complex generalization, comprehension of cause and effect, and high levels of abstraction and complex reasoning. (Gunnell & Ceci, 2010: 853; references omitted)

The question, therefore, is whether or not law reform can counteract the impact of rape myths, heuristic processing and pre-decisional distortion. I will examine this question in the next chapter when documenting the history of the modernisation of the substantive law of consent in both E&W and NSW.