Those verbs which have a quiescent  , or

, or  as the middle root letter generally give it up. Understand, when they are truly quiescent, like

as the middle root letter generally give it up. Understand, when they are truly quiescent, like  to rise up,

to rise up,  to return,

to return,  to rejoice; otherwise they are always retained, like

to rejoice; otherwise they are always retained, like  to ask,

to ask,  to pervert,

to pervert,  to be hostile, etc. Further, since those which have a quiescent

to be hostile, etc. Further, since those which have a quiescent  as the middle root letter change it most frequently into

as the middle root letter change it most frequently into  and, except for three or four times, none are found of which it is certain that they have an

and, except for three or four times, none are found of which it is certain that they have an  as the middle root letter, therefore the grammarians recognize two classes of verbs having a quiescent middle root letter, namely, one consisting of those which have a middle

as the middle root letter, therefore the grammarians recognize two classes of verbs having a quiescent middle root letter, namely, one consisting of those which have a middle  , and the other of those which have a middle

, and the other of those which have a middle  .

.

Moreover,  he got up, and

he got up, and  to be high, because they occur only once in Scripture, and like

to be high, because they occur only once in Scripture, and like  to thresh, whose

to thresh, whose  (which we have shown to happen often) is transposed, are considered as irregular. As a matter of fact, both those which have a middle

(which we have shown to happen often) is transposed, are considered as irregular. As a matter of fact, both those which have a middle  and those which have a middle

and those which have a middle  usually change them into a

usually change them into a  . For just as

. For just as  is replaced by

is replaced by  to get up, so also

to get up, so also  to rejoice is replaced by

to rejoice is replaced by  , and

, and  to pass the night by

to pass the night by  , etc. Hence I do not doubt the fact that these three quiescent groups belong to one class especially because their mode of conjugation is the same. To wit: the infinitive of the simple active verb is frequently

, etc. Hence I do not doubt the fact that these three quiescent groups belong to one class especially because their mode of conjugation is the same. To wit: the infinitive of the simple active verb is frequently  and

and  , or by dropping the

, or by dropping the  and

and  . Indeed it is very rarely found with an

. Indeed it is very rarely found with an  and those which have a

and those which have a  like

like  etc., we have shown that it frequently is changed to a

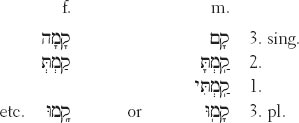

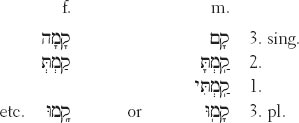

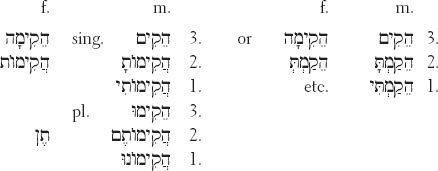

etc., we have shown that it frequently is changed to a  . In the past tense however the quiescent is most frequently dropped. Their form generally is:

. In the past tense however the quiescent is most frequently dropped. Their form generally is:

The past may also be punctuated with a  , and a cholem in place of a

, and a cholem in place of a  , like

, like  he despised,

he despised,  he lights,

he lights,  he was ashamed,

he was ashamed,  he died. Because the middle root letter is missing, the first is punctuated with the same vowel and the third root letter usually adheres to it. And there are many forms of the past tense which, like the verbs of the first conjugation, have a second vowel to which the third root adheres, (as we have shown in Chapter 14), which is either

he died. Because the middle root letter is missing, the first is punctuated with the same vowel and the third root letter usually adheres to it. And there are many forms of the past tense which, like the verbs of the first conjugation, have a second vowel to which the third root adheres, (as we have shown in Chapter 14), which is either  , or

, or  , or

, or  , or

, or  .

.

Next, just like those of the first conjugation, so also verbs of this conjugation change in the second and first persons the  and the

and the  into a

into a  , and they retain the cholem. But they have this unique quality, that in the third person singular of the feminine gender and in the third plural they do not change, like verbs of the first conjugation, the cholem, or the

, and they retain the cholem. But they have this unique quality, that in the third person singular of the feminine gender and in the third plural they do not change, like verbs of the first conjugation, the cholem, or the  , or the

, or the  into a sheva, even when the accent is not

into a sheva, even when the accent is not  , or

, or  . For, if it were to change into a sheva, the first root letter in the past would have too short a vowel, contrary to the common practice of the past simple form of the tense.

. For, if it were to change into a sheva, the first root letter in the past would have too short a vowel, contrary to the common practice of the past simple form of the tense.

Further, those which have a yod in the middle usually may retain it also in the past: for example  to quarrel has the past 3.

to quarrel has the past 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , etc., or 3.

, etc., or 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , 1.

, 1.  , etc. But others believe, and not without reason, that these are forms of the intensive verb (pi‘el) in place of

, etc. But others believe, and not without reason, that these are forms of the intensive verb (pi‘el) in place of  ; (of which in a moment), and also others believe them to be reciprocal verbs (hithpael) with the

; (of which in a moment), and also others believe them to be reciprocal verbs (hithpael) with the  omitted, for what reason I do not know.

omitted, for what reason I do not know.

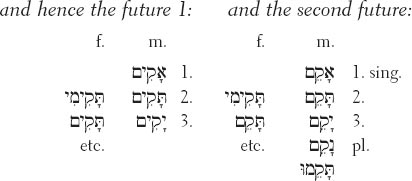

The imperative has all forms of the infinitive, namely:

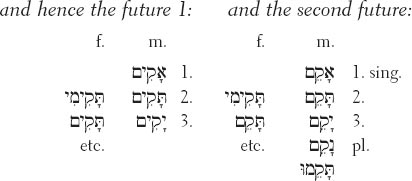

And these forms of the future  and

and  or

or  and

and  .

.

And to all these forms of the imperative and future the paragogic  is added for elegance, like

is added for elegance, like  get up,

get up,  return,

return,  I shall arise, etc.

I shall arise, etc.

The passive (niph‘al) keeps the form of the active (kal)  and the

and the  form becomes

form becomes  , and the

, and the  form becomes, I believe,

form becomes, I believe,  ; whence:

; whence:

The intensive form of the verb (pi‘el) is unable to double the middle radical  , seeing that it is a guttural. It may be compensated by a long vowel, but since it is most generally omitted, like the

, seeing that it is a guttural. It may be compensated by a long vowel, but since it is most generally omitted, like the  and

and  , on this account verbs of this conjugation are rarely able to double the second root letter, but generally double the third root letter. Accordingly from

, on this account verbs of this conjugation are rarely able to double the second root letter, but generally double the third root letter. Accordingly from  to get up it becomes

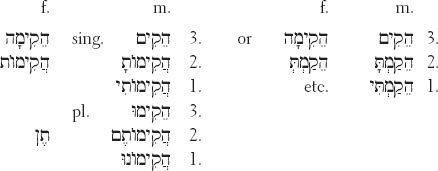

to get up it becomes  to erect; whence the pasts 3. m.

to erect; whence the pasts 3. m.  f.

f.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , f.

, f.  , etc., and the imperative m.

, etc., and the imperative m.  f.

f.  , etc., finally the futures 1.

, etc., finally the futures 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , etc.

, etc.

The passive intensive (pu‘al) is distinguished from the active (pi‘el) only by the patach. Namely, from the active (pi‘el)  , the passive becomes

, the passive becomes  to be erected. Whence the pasts 3. m.

to be erected. Whence the pasts 3. m.  , f.

, f.  , 2.

, 2.  , and the futures 1.

, and the futures 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  . This mode was common among the ancients in conjugating the verbs of this conjugation. But the later ones made from the verb

. This mode was common among the ancients in conjugating the verbs of this conjugation. But the later ones made from the verb  to owe or to be indebted the intensive (pi‘el)

to owe or to be indebted the intensive (pi‘el)  (perhaps not to be confused with

(perhaps not to be confused with  to love) and from

to love) and from  they made

they made  to establish, to affirm, and the others in this manner.

to establish, to affirm, and the others in this manner.

Then, not infrequently it is usual to double the first root letter, like  from

from  . But of this see Chapter 31.

. But of this see Chapter 31.

Beside these forms, some grammarians attribute another form in the intensive (pi‘el), namely, 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , 1.

, 1.  , etc., and it seems that they do not stray from the truth.

, etc., and it seems that they do not stray from the truth.

Further, the causative verbs (hiph‘il) lose the quiescent middle radical, and they become in the infinitive  , and

, and  ; in the past, however, they imitate the endings of the simple active (kal), or (which is more frequently observed in the Bible) the passive (niph‘al).

; in the past, however, they imitate the endings of the simple active (kal), or (which is more frequently observed in the Bible) the passive (niph‘al).

Thus it is

The Past Tense

The Imperative

But when the accent is put on the first syllable, the  changes to a -, namely,

changes to a -, namely,  , etc.

, etc.

The passive (hoph‘al) also losing the quiescent letter, has the infinitive  and

and  or

or  and

and  , and the past 3.

, and the past 3.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , f.

, f.  , or 3.

, or 3.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , and so forth; with which also the future agrees. For it is either 1.

, and so forth; with which also the future agrees. For it is either 1.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , f.

, f.  , etc., or

, etc., or  , etc.

, etc.

Next the reciprocal (hithpael) is formed, like in the other conjugations, from its intensive (pi‘el)  , namely by prefixing to it the syllable

, namely by prefixing to it the syllable  , and although the intensive (pi‘el) of this conjugation never ends in a

, and although the intensive (pi‘el) of this conjugation never ends in a  but always in a

but always in a  , the reciprocal (hithpael), however, is ended by both the

, the reciprocal (hithpael), however, is ended by both the  and the

and the  . Namely: The infinitive

. Namely: The infinitive  and

and  . The past 3. m.

. The past 3. m.  , f.

, f.  , etc. The imperative

, etc. The imperative  . The future

. The future  , etc.

, etc.

And there is nothing else to note here which they do not have in common with the verbs of the first conjugation.

Further, composite verbs of this and the third conjugation do not exist. For those which have the middle root letter  or

or  , and the third root letter

, and the third root letter  their middle root letter does not quiesce, like

their middle root letter does not quiesce, like  to spin,

to spin,  to borrow,

to borrow,  to be, etc.

to be, etc.

Those which have an  as the final root letter are only

as the final root letter are only  to come, and

to come, and  to restrain, whose simple active (kal) in the past always retains the

to restrain, whose simple active (kal) in the past always retains the  on account of the quiescent

on account of the quiescent  as

as  , and the imperative retains the cholem, namely m. s.

, and the imperative retains the cholem, namely m. s.  , f.

, f.  and

and  , m. p.

, m. p.  and

and  , f.

, f.  and

and  .1

.1

The future beside 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , etc., has also the fem. 1.

, etc., has also the fem. 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , 3.

, 3.  . Each of these verbs lacks the simple passive (niph‘al) and the intensive active and passive (pi‘el and pu‘al). The causative is generally terminated like

. Each of these verbs lacks the simple passive (niph‘al) and the intensive active and passive (pi‘el and pu‘al). The causative is generally terminated like  ; namely the past active (hiph‘il) 3. m.

; namely the past active (hiph‘il) 3. m.  , f.

, f.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , 1.

, 1.  , etc. But frequently it also is 3.

, etc. But frequently it also is 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , like

, like  , etc. The passive (hoph‘al) however is, 1.

, etc. The passive (hoph‘al) however is, 1.  etc. The reflexive (hithpael) is lacking in each, namely both

etc. The reflexive (hithpael) is lacking in each, namely both  and

and  . And concerning those whose third root letter is a

. And concerning those whose third root letter is a  or an

or an  much has already been observed, which was said in Chapter 24.

much has already been observed, which was said in Chapter 24.

, or

, or  as the middle root letter generally give it up. Understand, when they are truly quiescent, like

as the middle root letter generally give it up. Understand, when they are truly quiescent, like  to rise up,

to rise up,  to return,

to return,  to rejoice; otherwise they are always retained, like

to rejoice; otherwise they are always retained, like  to ask,

to ask,  to pervert,

to pervert,  to be hostile, etc. Further, since those which have a quiescent

to be hostile, etc. Further, since those which have a quiescent  as the middle root letter change it most frequently into

as the middle root letter change it most frequently into  and, except for three or four times, none are found of which it is certain that they have an

and, except for three or four times, none are found of which it is certain that they have an  as the middle root letter, therefore the grammarians recognize two classes of verbs having a quiescent middle root letter, namely, one consisting of those which have a middle

as the middle root letter, therefore the grammarians recognize two classes of verbs having a quiescent middle root letter, namely, one consisting of those which have a middle  , and the other of those which have a middle

, and the other of those which have a middle  .

. he got up, and

he got up, and  to be high, because they occur only once in Scripture, and like

to be high, because they occur only once in Scripture, and like  to thresh, whose

to thresh, whose  (which we have shown to happen often) is transposed, are considered as irregular. As a matter of fact, both those which have a middle

(which we have shown to happen often) is transposed, are considered as irregular. As a matter of fact, both those which have a middle  and those which have a middle

and those which have a middle  usually change them into a

usually change them into a  . For just as

. For just as  is replaced by

is replaced by  to get up, so also

to get up, so also  to rejoice is replaced by

to rejoice is replaced by  , and

, and  to pass the night by

to pass the night by  , etc. Hence I do not doubt the fact that these three quiescent groups belong to one class especially because their mode of conjugation is the same. To wit: the infinitive of the simple active verb is frequently

, etc. Hence I do not doubt the fact that these three quiescent groups belong to one class especially because their mode of conjugation is the same. To wit: the infinitive of the simple active verb is frequently  and

and  , or by dropping the

, or by dropping the  and

and  . Indeed it is very rarely found with an

. Indeed it is very rarely found with an  and those which have a

and those which have a  like

like  etc., we have shown that it frequently is changed to a

etc., we have shown that it frequently is changed to a  . In the past tense however the quiescent is most frequently dropped. Their form generally is:

. In the past tense however the quiescent is most frequently dropped. Their form generally is:

, and a cholem in place of a

, and a cholem in place of a  , like

, like  he despised,

he despised,  he lights,

he lights,  he was ashamed,

he was ashamed,  he died. Because the middle root letter is missing, the first is punctuated with the same vowel and the third root letter usually adheres to it. And there are many forms of the past tense which, like the verbs of the first conjugation, have a second vowel to which the third root adheres, (as we have shown in Chapter 14), which is either

he died. Because the middle root letter is missing, the first is punctuated with the same vowel and the third root letter usually adheres to it. And there are many forms of the past tense which, like the verbs of the first conjugation, have a second vowel to which the third root adheres, (as we have shown in Chapter 14), which is either  , or

, or  , or

, or  , or

, or  .

. and the

and the  into a

into a  , and they retain the cholem. But they have this unique quality, that in the third person singular of the feminine gender and in the third plural they do not change, like verbs of the first conjugation, the cholem, or the

, and they retain the cholem. But they have this unique quality, that in the third person singular of the feminine gender and in the third plural they do not change, like verbs of the first conjugation, the cholem, or the  , or the

, or the  into a sheva, even when the accent is not

into a sheva, even when the accent is not  , or

, or  . For, if it were to change into a sheva, the first root letter in the past would have too short a vowel, contrary to the common practice of the past simple form of the tense.

. For, if it were to change into a sheva, the first root letter in the past would have too short a vowel, contrary to the common practice of the past simple form of the tense. to quarrel has the past 3.

to quarrel has the past 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , etc., or 3.

, etc., or 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , 1.

, 1.  , etc. But others believe, and not without reason, that these are forms of the intensive verb (pi‘el) in place of

, etc. But others believe, and not without reason, that these are forms of the intensive verb (pi‘el) in place of  ; (of which in a moment), and also others believe them to be reciprocal verbs (hithpael) with the

; (of which in a moment), and also others believe them to be reciprocal verbs (hithpael) with the  omitted, for what reason I do not know.

omitted, for what reason I do not know.

and

and  or

or  and

and  .

. is added for elegance, like

is added for elegance, like  get up,

get up,  return,

return,  I shall arise, etc.

I shall arise, etc. and the

and the  form becomes

form becomes  , and the

, and the  form becomes, I believe,

form becomes, I believe,  ; whence:

; whence:

, seeing that it is a guttural. It may be compensated by a long vowel, but since it is most generally omitted, like the

, seeing that it is a guttural. It may be compensated by a long vowel, but since it is most generally omitted, like the  and

and  , on this account verbs of this conjugation are rarely able to double the second root letter, but generally double the third root letter. Accordingly from

, on this account verbs of this conjugation are rarely able to double the second root letter, but generally double the third root letter. Accordingly from  to get up it becomes

to get up it becomes  to erect; whence the pasts 3. m.

to erect; whence the pasts 3. m.  f.

f.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , f.

, f.  , etc., and the imperative m.

, etc., and the imperative m.  f.

f.  , etc., finally the futures 1.

, etc., finally the futures 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , etc.

, etc. , the passive becomes

, the passive becomes  to be erected. Whence the pasts 3. m.

to be erected. Whence the pasts 3. m.  , f.

, f.  , 2.

, 2.  , and the futures 1.

, and the futures 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  . This mode was common among the ancients in conjugating the verbs of this conjugation. But the later ones made from the verb

. This mode was common among the ancients in conjugating the verbs of this conjugation. But the later ones made from the verb  to owe or to be indebted the intensive (pi‘el)

to owe or to be indebted the intensive (pi‘el)  (perhaps not to be confused with

(perhaps not to be confused with  to love) and from

to love) and from  they made

they made  to establish, to affirm, and the others in this manner.

to establish, to affirm, and the others in this manner. from

from  . But of this see Chapter 31.

. But of this see Chapter 31. , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , 1.

, 1.  , etc., and it seems that they do not stray from the truth.

, etc., and it seems that they do not stray from the truth. , and

, and  ; in the past, however, they imitate the endings of the simple active (kal), or (which is more frequently observed in the Bible) the passive (niph‘al).

; in the past, however, they imitate the endings of the simple active (kal), or (which is more frequently observed in the Bible) the passive (niph‘al).

changes to a -, namely,

changes to a -, namely,  , etc.

, etc. and

and  or

or  and

and  , and the past 3.

, and the past 3.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , f.

, f.  , or 3.

, or 3.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , and so forth; with which also the future agrees. For it is either 1.

, and so forth; with which also the future agrees. For it is either 1.  , 2. m.

, 2. m.  , f.

, f.  , etc., or

, etc., or  , etc.

, etc. , namely by prefixing to it the syllable

, namely by prefixing to it the syllable  , and although the intensive (pi‘el) of this conjugation never ends in a

, and although the intensive (pi‘el) of this conjugation never ends in a  but always in a

but always in a  , the reciprocal (hithpael), however, is ended by both the

, the reciprocal (hithpael), however, is ended by both the  and the

and the  . Namely: The infinitive

. Namely: The infinitive  and

and  . The past 3. m.

. The past 3. m.  , f.

, f.  , etc. The imperative

, etc. The imperative  . The future

. The future  , etc.

, etc. or

or  , and the third root letter

, and the third root letter  their middle root letter does not quiesce, like

their middle root letter does not quiesce, like  to spin,

to spin,  to borrow,

to borrow,  to be, etc.

to be, etc. as the final root letter are only

as the final root letter are only  to come, and

to come, and  to restrain, whose simple active (kal) in the past always retains the

to restrain, whose simple active (kal) in the past always retains the  on account of the quiescent

on account of the quiescent  as

as  , and the imperative retains the cholem, namely m. s.

, and the imperative retains the cholem, namely m. s.  , f.

, f.  and

and  , m. p.

, m. p.  and

and  , f.

, f.  and

and  .

. , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , etc., has also the fem. 1.

, etc., has also the fem. 1.  , 2.

, 2.  , 3.

, 3.  . Each of these verbs lacks the simple passive (niph‘al) and the intensive active and passive (pi‘el and pu‘al). The causative is generally terminated like

. Each of these verbs lacks the simple passive (niph‘al) and the intensive active and passive (pi‘el and pu‘al). The causative is generally terminated like  ; namely the past active (hiph‘il) 3. m.

; namely the past active (hiph‘il) 3. m.  , f.

, f.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , 1.

, 1.  , etc. But frequently it also is 3.

, etc. But frequently it also is 3.  , 2.

, 2.  , f.

, f.  , like

, like  , etc. The passive (hoph‘al) however is, 1.

, etc. The passive (hoph‘al) however is, 1.  etc. The reflexive (hithpael) is lacking in each, namely both

etc. The reflexive (hithpael) is lacking in each, namely both  and

and  . And concerning those whose third root letter is a

. And concerning those whose third root letter is a  or an

or an  much has already been observed, which was said in Chapter 24.

much has already been observed, which was said in Chapter 24.

or

or  .—M.L.M.]

.—M.L.M.]