The rules which are usually transmitted concerning the accents are more of a hindrance than an aid to students of the Hebrew language. They should be tolerated only if they facilitate a proper understanding of the pronunciation of the language. But if you should consult the experts they would all be forced to admit that they do not know the reason for so great a number of accents. But to me it seems that there is a valid reason for it. At first I was strongly of the opinion that their inventor introduced them not only for the raising and the lowering of the voice and to adorn speech but also to indicate animated expression, which is usually produced by a change of voice, by the expression of the face, the movement of the body, the spreading of the hands, the winking of the eyes, the stamping of the feet, a curve of the mouth, a motion of the eyelids, spreading of the lips, and the various other gestures which aid a speaker to make clear his thoughts to his hearers. One tone of the voice expresses irony while another tone indicates simplicity. There is a tone in which we praise someone, another in which we express admiration, still another for vituperation, and yet another for mockery. Thus we change our voice and expression for every emotion. Nevertheless the originators of the letters in all languages failed to indicate these expressions in the written forms of speech. This is due to the fact that we can express our meaning much better orally than in writing. I suspected that the originator of the accents in the Hebrew language wanted to correct this fault. But when I examined the matter further I was unable to find this to be true. Indeed they succeeded rather to confuse not only these animated emotions but also speech itself. There is no distinction when the Scriptures speak ironically or when with simplicity and the same accent has different meanings in the composition of the parts of speech, and it also has the properties of a punctuation mark, and of a semicolon and of a double punctuation. So that it would seem that there is still a lack of accents with all the great number of them. Therefore I now believe that their introduction came after the Pharisees introduced the custom of reading the Bible in public assemblies every Sabbath in order that it should not be read too rapidly (as is usually done in the repetition of prayers). And for this reason I shall leave the minute regulations about them to the Pharisees and Massorites, and mention here only that which seems to have some purpose.

The accent serves to separate or join language and also to raise or depress a syllable. There is no accent indicating the end of a verse or a clause. These two points:  usually indicate a sign which is called a

usually indicate a sign which is called a  siluk, and generally, not always, as we have already shown, it declares the statement to be completed.1 But the parts of single sentences are separated by accents; and I understand these “parts of sentences” to consist of not only verbs but also cases of the noun. To be sure, the accent which here and there has the property of a comma is used also to separate the nominative and the verb from the accusative, and from the other cases. Understand, when the accusative follows the nominative; therefore, if the accusative is placed between the verb and the noun, then the verb, the accusative, and the nominative constitute only one part of the verse and are like two verbs which are united and joined together, and they have no other noun except the nominative case put between them. And if a verse has only one part to be separated it is separated by an accent which is called

siluk, and generally, not always, as we have already shown, it declares the statement to be completed.1 But the parts of single sentences are separated by accents; and I understand these “parts of sentences” to consist of not only verbs but also cases of the noun. To be sure, the accent which here and there has the property of a comma is used also to separate the nominative and the verb from the accusative, and from the other cases. Understand, when the accusative follows the nominative; therefore, if the accusative is placed between the verb and the noun, then the verb, the accusative, and the nominative constitute only one part of the verse and are like two verbs which are united and joined together, and they have no other noun except the nominative case put between them. And if a verse has only one part to be separated it is separated by an accent which is called  tarcha, which is denoted below the letter thus

tarcha, which is denoted below the letter thus  . But if it has two parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a

. But if it has two parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a  tarcha, the second also has an accent which is called

tarcha, the second also has an accent which is called  athnach, which is denoted under the letter thus

athnach, which is denoted under the letter thus  like

like  ; and this accent is preeminent among all which separate sentences into parts, as will become clear from what follows. A sentence may have only one athnach, except only rarely it may have two. But if a verse should have three parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a

; and this accent is preeminent among all which separate sentences into parts, as will become clear from what follows. A sentence may have only one athnach, except only rarely it may have two. But if a verse should have three parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a  tarcha, the second by an

tarcha, the second by an  athnach, and the third again by a

athnach, and the third again by a  tarcha. If it has four, however, the first is generally denoted by two dots above the word, like

tarcha. If it has four, however, the first is generally denoted by two dots above the word, like  deshe, which accent is usually called

deshe, which accent is usually called  zakef katon, the second

zakef katon, the second  , the third

, the third  and the fourth again

and the fourth again  . Further, if in a sentence five parts are to be separated, then the first generally should be denoted by a dot above the word which is called

. Further, if in a sentence five parts are to be separated, then the first generally should be denoted by a dot above the word which is called  rabi‘a, like

rabi‘a, like  , the second by a

, the second by a  , the third by a

, the third by a  , the fourth again by a

, the fourth again by a  , and the fifth by a

, and the fifth by a  . Finally, if there are six, then the first is a

. Finally, if there are six, then the first is a  , the second

, the second  , the third

, the third  , the fourth

, the fourth  , the fifth again

, the fifth again  , and finally the sixth

, and finally the sixth  . And in this manner, when still more parts which should be separated occur, many other signs are usually adduced, but the properties of

. And in this manner, when still more parts which should be separated occur, many other signs are usually adduced, but the properties of  and the

and the  are plainly similar; and they therefore often also displace one another; but I will refrain from speaking of these, as also of those which only serve to indicate an accent which is part of a phrase in which there are as a consequence of the divisions, some of these which are for this reason called by the grammarians serviles. But it should be pointed out that the

are plainly similar; and they therefore often also displace one another; but I will refrain from speaking of these, as also of those which only serve to indicate an accent which is part of a phrase in which there are as a consequence of the divisions, some of these which are for this reason called by the grammarians serviles. But it should be pointed out that the  serves not only to divide parts of sentences but also to indicate a

serves not only to divide parts of sentences but also to indicate a  and an

and an  . For after a

. For after a  no dividing accent may follow except an

no dividing accent may follow except an  or a

or a  and contrarily there is no

and contrarily there is no  or

or  which is not preceded by a

which is not preceded by a  , the reason for which we will tell presently. A word that has no accent either above or below is usually joined with the succeeding word by a straight line which the grammarians call a

, the reason for which we will tell presently. A word that has no accent either above or below is usually joined with the succeeding word by a straight line which the grammarians call a  makaf, like

makaf, like  ki-tob.

ki-tob.

Next, the accents serve, as we have said, both to elevate and depress a syllable. As we have already shown in these very examples, they should be placed either above or below the letter of the word whose vowel is to be elevated or depressed. Thus in  the

the  is above the

is above the  because it is pronounced déshe and not deshé; on the other hand

because it is pronounced déshe and not deshé; on the other hand  has the

has the  above the

above the  because it is pronounced elohím and not elóhim. Every word whose accent is below or above its last syllable is called

because it is pronounced elohím and not elóhim. Every word whose accent is below or above its last syllable is called  millera‘, which means from below; if, however, it is above or below the penultimate, it is called

millera‘, which means from below; if, however, it is above or below the penultimate, it is called  mille‘el, which means from above. But when a siluk is denoted neither below nor above but after a word, as also a makaf, then on that account the word before the siluk and makaf is denoted by a small line below it, namely under the syllable in which the accent should have been, like

mille‘el, which means from above. But when a siluk is denoted neither below nor above but after a word, as also a makaf, then on that account the word before the siluk and makaf is denoted by a small line below it, namely under the syllable in which the accent should have been, like  haaretz, where, before the siluk, under the

haaretz, where, before the siluk, under the  there is a small line indicating that the accent should have been under the kametz. So also

there is a small line indicating that the accent should have been under the kametz. So also  ‘oseh-peri has a little line, before the

‘oseh-peri has a little line, before the  , under the

, under the  , indicating that the cholem should be stressed. This line is usually called a

, indicating that the cholem should be stressed. This line is usually called a  ga’ya. It is not used, however, if the word before the makaf has only one vowel, like

ga’ya. It is not used, however, if the word before the makaf has only one vowel, like  .

.

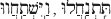

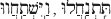

Polysyllables usually have two accents. One is either in the ultimate or penultimate, indicated as we have shown by whether the word is mille‘el or millera‘; the other is in the antepenultimate or its antecedent, indicating the syllable to be stressed, like  . And this accent is frequently a ga’ya, appearing almost always before a composite sheva. Further, you will observe not rarely that polysyllables have three accents, like

. And this accent is frequently a ga’ya, appearing almost always before a composite sheva. Further, you will observe not rarely that polysyllables have three accents, like  .

.

Moreover, in order to know which syllables should be stressed or lengthened, or where words should be marked by two or three accents, these rules should first be observed, namely: all vowels before a pronounced sheva are marked with a  ga’ya (of which I spoke in the previous chapter), that is, it is lengthened somewhat the better to know that the sheva which follows it belongs to the following syllable whence it follows that every vowel before a compound sheva, be it a short or a long vowel, should be marked with this accent, like

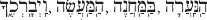

ga’ya (of which I spoke in the previous chapter), that is, it is lengthened somewhat the better to know that the sheva which follows it belongs to the following syllable whence it follows that every vowel before a compound sheva, be it a short or a long vowel, should be marked with this accent, like  . For a compound sheva can never be silenced, that is, it belongs not to the preceding but to the succeeding syllable. Next, it follows that a long vowel before a simple sheva should be stressed or it should be marked with this accent, so that it will be clearly understood that the sheva was not lost from it but belongs to the succeeding syllable. Hence,

. For a compound sheva can never be silenced, that is, it belongs not to the preceding but to the succeeding syllable. Next, it follows that a long vowel before a simple sheva should be stressed or it should be marked with this accent, so that it will be clearly understood that the sheva was not lost from it but belongs to the succeeding syllable. Hence,  are marked with the accent

are marked with the accent  ; and also

; and also  , although it is short, yet on account of the succeeding sheva its pronunciation is lengthened. But although a sheva under a dageshed letter should also be pronounced, nevertheless, the vowel preceding it is not marked with a ga’ya unless the letter to be doubled is one of those which do not admit a dagesh point, or may not be doubled, of which see Chapter 2; and I suppose that this is because a dagesh means that the first of the doubled letters (the assumed letter) belongs to the preceding vowel, its sheva having been swallowed up with it; and what is more a vowel before a sheva under a dageshed letter should be considered like a vowel which is followed by two shevas, the first of which, as we have said above, should be silent, and the second pronounced, or the first of which should belong to the preceding, and the second to the succeeding syllable.

, although it is short, yet on account of the succeeding sheva its pronunciation is lengthened. But although a sheva under a dageshed letter should also be pronounced, nevertheless, the vowel preceding it is not marked with a ga’ya unless the letter to be doubled is one of those which do not admit a dagesh point, or may not be doubled, of which see Chapter 2; and I suppose that this is because a dagesh means that the first of the doubled letters (the assumed letter) belongs to the preceding vowel, its sheva having been swallowed up with it; and what is more a vowel before a sheva under a dageshed letter should be considered like a vowel which is followed by two shevas, the first of which, as we have said above, should be silent, and the second pronounced, or the first of which should belong to the preceding, and the second to the succeeding syllable.

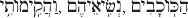

Next, if a vowel after any sheva requires to be lengthened then the vowel before the same sheva is lengthened; and this rule is always true, whether the sheva is expressed or assumed; for example,  , since the patach after the simple sheva should be lengthened on account of the composite sheva after it, for the same reason also the patach before the same simple sheva is lengthened. Thus also

, since the patach after the simple sheva should be lengthened on account of the composite sheva after it, for the same reason also the patach before the same simple sheva is lengthened. Thus also  , etc., for this very same reason have two ga’yas each. And I say the same is true when a sheva is assumed, like

, etc., for this very same reason have two ga’yas each. And I say the same is true when a sheva is assumed, like  , where under each

, where under each  there is a ga’ya because it should be read

there is a ga’ya because it should be read  the kametz indeed does have a sheva before it, which is compensated by the dagesh point, and, because of the composite sheva following it, it should be lengthened. The vowel before this sheva that is compensated by a dagesh point is also lengthened. So

the kametz indeed does have a sheva before it, which is compensated by the dagesh point, and, because of the composite sheva following it, it should be lengthened. The vowel before this sheva that is compensated by a dagesh point is also lengthened. So  , and many others of this type are denoted by a doubling of the ga’ya.

, and many others of this type are denoted by a doubling of the ga’ya.

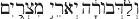

Two long vowels without an accent or a ga’ya in the same word are not to be found. If indeed the penultimate and antepenultimate syllables should be long, or if an accent should be necessary in the antepenultimate, or if in the ultimate, then the antepenultimate will have a ga’ya, like  whose kametz is lengthened when the accent is in the ultimate, otherwise, namely when the accent is in the penultimate, it is omitted, like

whose kametz is lengthened when the accent is in the ultimate, otherwise, namely when the accent is in the penultimate, it is omitted, like  ; thus

; thus  , etc., have a ga’ya in the antepenultimate; but if a word should have many long vowels it will always be observed that no two long vowels occur without either an accent or a ga’ya, like

, etc., have a ga’ya in the antepenultimate; but if a word should have many long vowels it will always be observed that no two long vowels occur without either an accent or a ga’ya, like  .

.

And this should be noted, a kibbutz sometimes replaces a shurek, and then it should be considered as long, like  where, because the shurek of the noun

where, because the shurek of the noun  has been changed into a kibbutz, the kibbutz is lengthened like a long vowel; otherwise it is always short.

has been changed into a kibbutz, the kibbutz is lengthened like a long vowel; otherwise it is always short.

Next, it should be noted that a short vowel to which a sheva adheres is to be considered as a long one, like  , etc., where a long before a short, to which a sheva adheres, is lengthened, like a long before a long, which does not have an accent; thus also the two first vowels in

, etc., where a long before a short, to which a sheva adheres, is lengthened, like a long before a long, which does not have an accent; thus also the two first vowels in  are long because a sheva adheres to each, the first being expressed and the latter, however, compensated by the dagesh in the

are long because a sheva adheres to each, the first being expressed and the latter, however, compensated by the dagesh in the  . Short vowels are excepted when they frequently replace a simple sheva so that no two should occur at the beginning of a word, as we have already pointed out in Chapter 3, for example, the first vowel in

. Short vowels are excepted when they frequently replace a simple sheva so that no two should occur at the beginning of a word, as we have already pointed out in Chapter 3, for example, the first vowel in  is short because it is in place of a short sheva, because it usurps the place of a sheva. It happens then that a short vowel before a short vowel is lengthened because the second short is put in place of a compound sheva to which, as we have said, a ga’ya always antecedes, like

is short because it is in place of a short sheva, because it usurps the place of a sheva. It happens then that a short vowel before a short vowel is lengthened because the second short is put in place of a compound sheva to which, as we have said, a ga’ya always antecedes, like  , because it is written in place of

, because it is written in place of  .

.

Finally, a  vav before a

vav before a  yod with a - patach is denoted variously, with and without a ga’ya, like

yod with a - patach is denoted variously, with and without a ga’ya, like  and

and  .

.

And these are the principal rules of this accent as far as it is possible to know them from the vowels alone. There still remains another to be recognized concerning the preposition, which we will explain in its place.

For the rest, I do not have anything to say about the fact that the Jews, because of the musical accent ~, which they call a zarka, now bring in a ga’ya into the syllable antecedent to it, because it is not followed by those who either wish to speak Hebrew or to chant it.

This, however, should be noted, that frequently another accent is put in place of a ga’ya; indeed, some words have two accents. And one of their syllables is lengthened, which would otherwise not be lengthened because of the preceding rules.

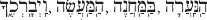

And this, I say, therefore, is because two different accents which should precede servile accents follow one another alternately only rarely; for example, after an athnach a siluk does not follow immediately, and not a  and vice versa after a siluk only most rarely will a zakef katon follow, and not an athnach. But if the word which follows one of these accents has to have one of them, then at that place two accents are denoted, and one usually lengthens its syllable, however, it would otherwise not be lengthened, like Isaiah chap. 7, vs. 18,

and vice versa after a siluk only most rarely will a zakef katon follow, and not an athnach. But if the word which follows one of these accents has to have one of them, then at that place two accents are denoted, and one usually lengthens its syllable, however, it would otherwise not be lengthened, like Isaiah chap. 7, vs. 18,  where

where  , because of the zakef katon, has another accent over the

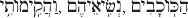

, because of the zakef katon, has another accent over the  , its syllable being lengthened contrary to the general rule, on account of the preceding athnach. Thus also Numbers chap. 28, vs. 20 and 28

, its syllable being lengthened contrary to the general rule, on account of the preceding athnach. Thus also Numbers chap. 28, vs. 20 and 28  , because it follows immediately after a siluk, has two accents, and the vowel below the

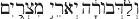

, because it follows immediately after a siluk, has two accents, and the vowel below the  , contrary to the general rule, is lengthened; and also Deuteronomy chap. 12, vs. 1

, contrary to the general rule, is lengthened; and also Deuteronomy chap. 12, vs. 1  . And for this reason, also, Deuteronomy chap. 13, vs. 12,

. And for this reason, also, Deuteronomy chap. 13, vs. 12,  contrary to the general rule of the makaf, an accent is put above

contrary to the general rule of the makaf, an accent is put above  ; and in this manner many examples are found and many more of them where the ga’ya is changed into an accent for one reason or another.

; and in this manner many examples are found and many more of them where the ga’ya is changed into an accent for one reason or another.

Finally, it should be noted that among the dividing accents there is one which is called  kadma, which is always denoted above the end of a word in this manner

kadma, which is always denoted above the end of a word in this manner  and in this way is it indeed differentiated from another of the serviles which is called

and in this way is it indeed differentiated from another of the serviles which is called  azla, which is always denoted above the syllable in which the accent should be. If then the word accented by this

azla, which is always denoted above the syllable in which the accent should be. If then the word accented by this  should be denoted as mille‘el, it needs another accent which indicates that the accent should be in the penultimate; like

should be denoted as mille‘el, it needs another accent which indicates that the accent should be in the penultimate; like  , in case that this accent should be denoted, over the dalet the accent

, in case that this accent should be denoted, over the dalet the accent  should also be denoted so that it will be known that the word is mille‘el

should also be denoted so that it will be known that the word is mille‘el  .

.

In addition to this, I have found another reason why a word may be denoted by a dual accent; namely when a millera‘ word, for reasons I shall mention later, reverts to a mille‘el, like the syllables before being held, the accent remains in the ultimate, and the penultimate where there should also be an accent is denoted by another accent. But this rule is plainly useless for the second accent is of no use whatever.

And now it is time to show which words have an accent in the ultimate and which in the antepenultimate, that is, which should be  and which

and which  ; but since this cannot be discerned from vowels and letters alone, I shall postpone the matter until I shall come to the verbs. Here I will add only this, namely that the athnach and the siluk often render words which are millera’ into mille’el. That is to say when their syllables, both ultimate and antepenultimate, are long, as when

; but since this cannot be discerned from vowels and letters alone, I shall postpone the matter until I shall come to the verbs. Here I will add only this, namely that the athnach and the siluk often render words which are millera’ into mille’el. That is to say when their syllables, both ultimate and antepenultimate, are long, as when  is designated by accent athnach or siluk, it can be rendered

is designated by accent athnach or siluk, it can be rendered  , like

, like  But if the penultimate should be a sheva which, as we have already said, never has an accent, then the verbs change the

But if the penultimate should be a sheva which, as we have already said, never has an accent, then the verbs change the  into a kametz and nouns into a

into a kametz and nouns into a  . Thus, if

. Thus, if  is denoted with an athnach the sheva under the

is denoted with an athnach the sheva under the  changes into a

changes into a  and it becomes

and it becomes  ; but, in place of

; but, in place of  , if it has an athnach, it is

, if it has an athnach, it is  In participles of the feminine gender, however, it changes into both a segol and a kametz; and this also happens when the accent should be

In participles of the feminine gender, however, it changes into both a segol and a kametz; and this also happens when the accent should be  .

.

Next, it should be noted that the accent athnach and the siluk destroy the properties of a dividing accent before them and, as it were, snatch them away. Whence it is that the only dividing accent which may precede these two accents is a tarcha which, therefore, indicates that an athnach or siluk follows and which also, therefore, does not have the properties of a dividing accent; for it does not render the words  and it can often be followed by a zakef katon or another dividing accent and it may be followed immediately after itself by an athnach or siluk. Wherefore, with what we have said above, that two dividing accents do not follow themselves immediately, it is understood concerning all except the

and it can often be followed by a zakef katon or another dividing accent and it may be followed immediately after itself by an athnach or siluk. Wherefore, with what we have said above, that two dividing accents do not follow themselves immediately, it is understood concerning all except the  which, as we have said, has lost on that account the dividing properties of an athnach and siluk.

which, as we have said, has lost on that account the dividing properties of an athnach and siluk.

usually indicate a sign which is called a

usually indicate a sign which is called a  siluk, and generally, not always, as we have already shown, it declares the statement to be completed.1 But the parts of single sentences are separated by accents; and I understand these “parts of sentences” to consist of not only verbs but also cases of the noun. To be sure, the accent which here and there has the property of a comma is used also to separate the nominative and the verb from the accusative, and from the other cases. Understand, when the accusative follows the nominative; therefore, if the accusative is placed between the verb and the noun, then the verb, the accusative, and the nominative constitute only one part of the verse and are like two verbs which are united and joined together, and they have no other noun except the nominative case put between them. And if a verse has only one part to be separated it is separated by an accent which is called

siluk, and generally, not always, as we have already shown, it declares the statement to be completed.1 But the parts of single sentences are separated by accents; and I understand these “parts of sentences” to consist of not only verbs but also cases of the noun. To be sure, the accent which here and there has the property of a comma is used also to separate the nominative and the verb from the accusative, and from the other cases. Understand, when the accusative follows the nominative; therefore, if the accusative is placed between the verb and the noun, then the verb, the accusative, and the nominative constitute only one part of the verse and are like two verbs which are united and joined together, and they have no other noun except the nominative case put between them. And if a verse has only one part to be separated it is separated by an accent which is called  tarcha, which is denoted below the letter thus

tarcha, which is denoted below the letter thus  . But if it has two parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a

. But if it has two parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a  tarcha, the second also has an accent which is called

tarcha, the second also has an accent which is called  athnach, which is denoted under the letter thus

athnach, which is denoted under the letter thus  like

like  ; and this accent is preeminent among all which separate sentences into parts, as will become clear from what follows. A sentence may have only one athnach, except only rarely it may have two. But if a verse should have three parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a

; and this accent is preeminent among all which separate sentences into parts, as will become clear from what follows. A sentence may have only one athnach, except only rarely it may have two. But if a verse should have three parts to be divided, then the first is denoted by a  tarcha, the second by an

tarcha, the second by an  athnach, and the third again by a

athnach, and the third again by a  tarcha. If it has four, however, the first is generally denoted by two dots above the word, like

tarcha. If it has four, however, the first is generally denoted by two dots above the word, like  deshe, which accent is usually called

deshe, which accent is usually called  zakef katon, the second

zakef katon, the second  , the third

, the third  and the fourth again

and the fourth again  . Further, if in a sentence five parts are to be separated, then the first generally should be denoted by a dot above the word which is called

. Further, if in a sentence five parts are to be separated, then the first generally should be denoted by a dot above the word which is called  rabi‘a, like

rabi‘a, like  , the second by a

, the second by a  , the third by a

, the third by a  , the fourth again by a

, the fourth again by a  , and the fifth by a

, and the fifth by a  . Finally, if there are six, then the first is a

. Finally, if there are six, then the first is a  , the second

, the second  , the third

, the third  , the fourth

, the fourth  , the fifth again

, the fifth again  , and finally the sixth

, and finally the sixth  . And in this manner, when still more parts which should be separated occur, many other signs are usually adduced, but the properties of

. And in this manner, when still more parts which should be separated occur, many other signs are usually adduced, but the properties of  and the

and the  are plainly similar; and they therefore often also displace one another; but I will refrain from speaking of these, as also of those which only serve to indicate an accent which is part of a phrase in which there are as a consequence of the divisions, some of these which are for this reason called by the grammarians serviles. But it should be pointed out that the

are plainly similar; and they therefore often also displace one another; but I will refrain from speaking of these, as also of those which only serve to indicate an accent which is part of a phrase in which there are as a consequence of the divisions, some of these which are for this reason called by the grammarians serviles. But it should be pointed out that the  serves not only to divide parts of sentences but also to indicate a

serves not only to divide parts of sentences but also to indicate a  and an

and an  . For after a

. For after a  no dividing accent may follow except an

no dividing accent may follow except an  or a

or a  and contrarily there is no

and contrarily there is no  or

or  which is not preceded by a

which is not preceded by a  , the reason for which we will tell presently. A word that has no accent either above or below is usually joined with the succeeding word by a straight line which the grammarians call a

, the reason for which we will tell presently. A word that has no accent either above or below is usually joined with the succeeding word by a straight line which the grammarians call a  makaf, like

makaf, like  ki-tob.

ki-tob. the

the  is above the

is above the  because it is pronounced déshe and not deshé; on the other hand

because it is pronounced déshe and not deshé; on the other hand  has the

has the  above the

above the  because it is pronounced elohím and not elóhim. Every word whose accent is below or above its last syllable is called

because it is pronounced elohím and not elóhim. Every word whose accent is below or above its last syllable is called  millera‘, which means from below; if, however, it is above or below the penultimate, it is called

millera‘, which means from below; if, however, it is above or below the penultimate, it is called  mille‘el, which means from above. But when a siluk is denoted neither below nor above but after a word, as also a makaf, then on that account the word before the siluk and makaf is denoted by a small line below it, namely under the syllable in which the accent should have been, like

mille‘el, which means from above. But when a siluk is denoted neither below nor above but after a word, as also a makaf, then on that account the word before the siluk and makaf is denoted by a small line below it, namely under the syllable in which the accent should have been, like  haaretz, where, before the siluk, under the

haaretz, where, before the siluk, under the  there is a small line indicating that the accent should have been under the kametz. So also

there is a small line indicating that the accent should have been under the kametz. So also  ‘oseh-peri has a little line, before the

‘oseh-peri has a little line, before the  , under the

, under the  , indicating that the cholem should be stressed. This line is usually called a

, indicating that the cholem should be stressed. This line is usually called a  ga’ya. It is not used, however, if the word before the makaf has only one vowel, like

ga’ya. It is not used, however, if the word before the makaf has only one vowel, like  .

. . And this accent is frequently a ga’ya, appearing almost always before a composite sheva. Further, you will observe not rarely that polysyllables have three accents, like

. And this accent is frequently a ga’ya, appearing almost always before a composite sheva. Further, you will observe not rarely that polysyllables have three accents, like  .

. ga’ya (of which I spoke in the previous chapter), that is, it is lengthened somewhat the better to know that the sheva which follows it belongs to the following syllable whence it follows that every vowel before a compound sheva, be it a short or a long vowel, should be marked with this accent, like

ga’ya (of which I spoke in the previous chapter), that is, it is lengthened somewhat the better to know that the sheva which follows it belongs to the following syllable whence it follows that every vowel before a compound sheva, be it a short or a long vowel, should be marked with this accent, like  . For a compound sheva can never be silenced, that is, it belongs not to the preceding but to the succeeding syllable. Next, it follows that a long vowel before a simple sheva should be stressed or it should be marked with this accent, so that it will be clearly understood that the sheva was not lost from it but belongs to the succeeding syllable. Hence,

. For a compound sheva can never be silenced, that is, it belongs not to the preceding but to the succeeding syllable. Next, it follows that a long vowel before a simple sheva should be stressed or it should be marked with this accent, so that it will be clearly understood that the sheva was not lost from it but belongs to the succeeding syllable. Hence,  are marked with the accent

are marked with the accent  ; and also

; and also  , although it is short, yet on account of the succeeding sheva its pronunciation is lengthened. But although a sheva under a dageshed letter should also be pronounced, nevertheless, the vowel preceding it is not marked with a ga’ya unless the letter to be doubled is one of those which do not admit a dagesh point, or may not be doubled, of which see Chapter 2; and I suppose that this is because a dagesh means that the first of the doubled letters (the assumed letter) belongs to the preceding vowel, its sheva having been swallowed up with it; and what is more a vowel before a sheva under a dageshed letter should be considered like a vowel which is followed by two shevas, the first of which, as we have said above, should be silent, and the second pronounced, or the first of which should belong to the preceding, and the second to the succeeding syllable.

, although it is short, yet on account of the succeeding sheva its pronunciation is lengthened. But although a sheva under a dageshed letter should also be pronounced, nevertheless, the vowel preceding it is not marked with a ga’ya unless the letter to be doubled is one of those which do not admit a dagesh point, or may not be doubled, of which see Chapter 2; and I suppose that this is because a dagesh means that the first of the doubled letters (the assumed letter) belongs to the preceding vowel, its sheva having been swallowed up with it; and what is more a vowel before a sheva under a dageshed letter should be considered like a vowel which is followed by two shevas, the first of which, as we have said above, should be silent, and the second pronounced, or the first of which should belong to the preceding, and the second to the succeeding syllable. , since the patach after the simple sheva should be lengthened on account of the composite sheva after it, for the same reason also the patach before the same simple sheva is lengthened. Thus also

, since the patach after the simple sheva should be lengthened on account of the composite sheva after it, for the same reason also the patach before the same simple sheva is lengthened. Thus also  , etc., for this very same reason have two ga’yas each. And I say the same is true when a sheva is assumed, like

, etc., for this very same reason have two ga’yas each. And I say the same is true when a sheva is assumed, like  , where under each

, where under each  there is a ga’ya because it should be read

there is a ga’ya because it should be read  the kametz indeed does have a sheva before it, which is compensated by the dagesh point, and, because of the composite sheva following it, it should be lengthened. The vowel before this sheva that is compensated by a dagesh point is also lengthened. So

the kametz indeed does have a sheva before it, which is compensated by the dagesh point, and, because of the composite sheva following it, it should be lengthened. The vowel before this sheva that is compensated by a dagesh point is also lengthened. So  , and many others of this type are denoted by a doubling of the ga’ya.

, and many others of this type are denoted by a doubling of the ga’ya. whose kametz is lengthened when the accent is in the ultimate, otherwise, namely when the accent is in the penultimate, it is omitted, like

whose kametz is lengthened when the accent is in the ultimate, otherwise, namely when the accent is in the penultimate, it is omitted, like  ; thus

; thus  , etc., have a ga’ya in the antepenultimate; but if a word should have many long vowels it will always be observed that no two long vowels occur without either an accent or a ga’ya, like

, etc., have a ga’ya in the antepenultimate; but if a word should have many long vowels it will always be observed that no two long vowels occur without either an accent or a ga’ya, like  .

. where, because the shurek of the noun

where, because the shurek of the noun  has been changed into a kibbutz, the kibbutz is lengthened like a long vowel; otherwise it is always short.

has been changed into a kibbutz, the kibbutz is lengthened like a long vowel; otherwise it is always short. , etc., where a long before a short, to which a sheva adheres, is lengthened, like a long before a long, which does not have an accent; thus also the two first vowels in

, etc., where a long before a short, to which a sheva adheres, is lengthened, like a long before a long, which does not have an accent; thus also the two first vowels in  are long because a sheva adheres to each, the first being expressed and the latter, however, compensated by the dagesh in the

are long because a sheva adheres to each, the first being expressed and the latter, however, compensated by the dagesh in the  . Short vowels are excepted when they frequently replace a simple sheva so that no two should occur at the beginning of a word, as we have already pointed out in Chapter 3, for example, the first vowel in

. Short vowels are excepted when they frequently replace a simple sheva so that no two should occur at the beginning of a word, as we have already pointed out in Chapter 3, for example, the first vowel in  is short because it is in place of a short sheva, because it usurps the place of a sheva. It happens then that a short vowel before a short vowel is lengthened because the second short is put in place of a compound sheva to which, as we have said, a ga’ya always antecedes, like

is short because it is in place of a short sheva, because it usurps the place of a sheva. It happens then that a short vowel before a short vowel is lengthened because the second short is put in place of a compound sheva to which, as we have said, a ga’ya always antecedes, like  , because it is written in place of

, because it is written in place of  .

. vav before a

vav before a  yod with a - patach is denoted variously, with and without a ga’ya, like

yod with a - patach is denoted variously, with and without a ga’ya, like  and

and  .

. and vice versa after a siluk only most rarely will a zakef katon follow, and not an athnach. But if the word which follows one of these accents has to have one of them, then at that place two accents are denoted, and one usually lengthens its syllable, however, it would otherwise not be lengthened, like Isaiah chap. 7, vs. 18,

and vice versa after a siluk only most rarely will a zakef katon follow, and not an athnach. But if the word which follows one of these accents has to have one of them, then at that place two accents are denoted, and one usually lengthens its syllable, however, it would otherwise not be lengthened, like Isaiah chap. 7, vs. 18,  where

where  , because of the zakef katon, has another accent over the

, because of the zakef katon, has another accent over the  , its syllable being lengthened contrary to the general rule, on account of the preceding athnach. Thus also Numbers chap. 28, vs. 20 and 28

, its syllable being lengthened contrary to the general rule, on account of the preceding athnach. Thus also Numbers chap. 28, vs. 20 and 28  , because it follows immediately after a siluk, has two accents, and the vowel below the

, because it follows immediately after a siluk, has two accents, and the vowel below the  , contrary to the general rule, is lengthened; and also Deuteronomy chap. 12, vs. 1

, contrary to the general rule, is lengthened; and also Deuteronomy chap. 12, vs. 1  . And for this reason, also, Deuteronomy chap. 13, vs. 12,

. And for this reason, also, Deuteronomy chap. 13, vs. 12,  contrary to the general rule of the makaf, an accent is put above

contrary to the general rule of the makaf, an accent is put above  ; and in this manner many examples are found and many more of them where the ga’ya is changed into an accent for one reason or another.

; and in this manner many examples are found and many more of them where the ga’ya is changed into an accent for one reason or another. kadma, which is always denoted above the end of a word in this manner

kadma, which is always denoted above the end of a word in this manner  and in this way is it indeed differentiated from another of the serviles which is called

and in this way is it indeed differentiated from another of the serviles which is called  azla, which is always denoted above the syllable in which the accent should be. If then the word accented by this

azla, which is always denoted above the syllable in which the accent should be. If then the word accented by this  should be denoted as mille‘el, it needs another accent which indicates that the accent should be in the penultimate; like

should be denoted as mille‘el, it needs another accent which indicates that the accent should be in the penultimate; like  , in case that this accent should be denoted, over the dalet the accent

, in case that this accent should be denoted, over the dalet the accent  should also be denoted so that it will be known that the word is mille‘el

should also be denoted so that it will be known that the word is mille‘el  .

. and which

and which  ; but since this cannot be discerned from vowels and letters alone, I shall postpone the matter until I shall come to the verbs. Here I will add only this, namely that the athnach and the siluk often render words which are millera’ into mille’el. That is to say when their syllables, both ultimate and antepenultimate, are long, as when

; but since this cannot be discerned from vowels and letters alone, I shall postpone the matter until I shall come to the verbs. Here I will add only this, namely that the athnach and the siluk often render words which are millera’ into mille’el. That is to say when their syllables, both ultimate and antepenultimate, are long, as when  is designated by accent athnach or siluk, it can be rendered

is designated by accent athnach or siluk, it can be rendered  , like

, like  But if the penultimate should be a sheva which, as we have already said, never has an accent, then the verbs change the

But if the penultimate should be a sheva which, as we have already said, never has an accent, then the verbs change the  into a kametz and nouns into a

into a kametz and nouns into a  . Thus, if

. Thus, if  is denoted with an athnach the sheva under the

is denoted with an athnach the sheva under the  changes into a

changes into a  and it becomes

and it becomes  ; but, in place of

; but, in place of  , if it has an athnach, it is

, if it has an athnach, it is  In participles of the feminine gender, however, it changes into both a segol and a kametz; and this also happens when the accent should be

In participles of the feminine gender, however, it changes into both a segol and a kametz; and this also happens when the accent should be  .

. and it can often be followed by a zakef katon or another dividing accent and it may be followed immediately after itself by an athnach or siluk. Wherefore, with what we have said above, that two dividing accents do not follow themselves immediately, it is understood concerning all except the

and it can often be followed by a zakef katon or another dividing accent and it may be followed immediately after itself by an athnach or siluk. Wherefore, with what we have said above, that two dividing accents do not follow themselves immediately, it is understood concerning all except the  which, as we have said, has lost on that account the dividing properties of an athnach and siluk.

which, as we have said, has lost on that account the dividing properties of an athnach and siluk.