Things are expressed either absolutely or in relationship to other things, so that they may be indicated more clearly and distinctly. For example: “The earth is big,” “the earth” is expressed in an absolute state; but “God’s earth is big,” here, “earth” is in a relative state because it is expressed more effectively or indicated more clearly, and this is called the construct state. I will now tell in orderly fashion the manner in which this is usually expressed, beginning with the manner of the singular.

Nouns which ended in a  preceded by a kametz or a cholem, change the

preceded by a kametz or a cholem, change the  into a

into a  and the kametz

and the kametz  into a patach -. Thus

into a patach -. Thus  becomes in construct case

becomes in construct case  , and means somebody’s prayer. So

, and means somebody’s prayer. So  to do becomes in construct case

to do becomes in construct case  somebody’s doing, as in

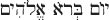

somebody’s doing, as in  the day of the Lord God’s doing.

the day of the Lord God’s doing.

Those which have a double or only a single kametz in the absolute, change in the construct case the penultimate into a sheva and the ultimate into a patach, like  from

from  a word,

a word,  a talent of gold from

a talent of gold from  a talent,

a talent,  from

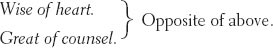

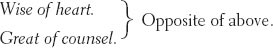

from  a wise man, as Job in chapter 9 called God

a wise man, as Job in chapter 9 called God  wise of heart. So

wise of heart. So  blessed,

blessed,  peace,

peace,  visiting,

visiting,  old, etc., change the penultimate kametz to a sheva; so also

old, etc., change the penultimate kametz to a sheva; so also  justice,

justice,  a blessing, change the ultimate kametz into a patach, and the penultimate into a sheva, and the

a blessing, change the ultimate kametz into a patach, and the penultimate into a sheva, and the  into a

into a  as we have already said, thus becoming

as we have already said, thus becoming  . It is only because two shevas cannot occur at the beginning of a word that the first sheva is changed into chirek. This is always the case, I cannot reiterate this too often, with every chirek and patach before a sheva.

. It is only because two shevas cannot occur at the beginning of a word that the first sheva is changed into chirek. This is always the case, I cannot reiterate this too often, with every chirek and patach before a sheva.

A penultimate tsere is sometimes changed into a sheva, and an ultimate sometimes to a patach, like  from

from  hair, and

hair, and  from

from  a corner,

a corner,  from

from  an elder,

an elder,  from

from  a stick. But most frequently both the ultimate and the penultimate remain unchanged. Indeed, these and many others like them are completely uncertain; at times a noun changes the tsere and at times it retains it, which shows that in the Scriptures the dialects are mixed up. Thus everyone is at liberty either to change or to leave both the tsere and the kametz in the ultimate; except for the tsere before a

a stick. But most frequently both the ultimate and the penultimate remain unchanged. Indeed, these and many others like them are completely uncertain; at times a noun changes the tsere and at times it retains it, which shows that in the Scriptures the dialects are mixed up. Thus everyone is at liberty either to change or to leave both the tsere and the kametz in the ultimate; except for the tsere before a  which always should be retained because of common usage, like

which always should be retained because of common usage, like  a temple, for example. The word

a temple, for example. The word  occurs everywhere in the Scriptures in the construct case as

occurs everywhere in the Scriptures in the construct case as  , and

, and  and

and  become

become  and

and  . Therefore I say everyone is free to write

. Therefore I say everyone is free to write  for

for  and

and  for

for  , even though neither is found in the Scriptures. And what I have said about the tsere and the kametz should be said about everything that does not follow a fixed rule. But of this I shall treat copiously in another place. Here let me add a word concerning the matter of which I have spoken thus far, and which I regard to be no less essential toward the purpose of this chapter and toward the general knowledge of this language.

, even though neither is found in the Scriptures. And what I have said about the tsere and the kametz should be said about everything that does not follow a fixed rule. But of this I shall treat copiously in another place. Here let me add a word concerning the matter of which I have spoken thus far, and which I regard to be no less essential toward the purpose of this chapter and toward the general knowledge of this language.

In the previous chapter, we have said that the feminine endings  and

and  and the plural

and the plural  are characteristic of adjectives and participles, doubtless because the same noun may have an adjective, which sometimes is referred to as masculine and sometimes as feminine, and for that reason, at one time or another requires either of two endings. This is not the case with the substantive nouns and, therefore, it sometimes happens that substantive nouns which express neither masculine nor feminine are referred to as of feminine gender when they end in

are characteristic of adjectives and participles, doubtless because the same noun may have an adjective, which sometimes is referred to as masculine and sometimes as feminine, and for that reason, at one time or another requires either of two endings. This is not the case with the substantive nouns and, therefore, it sometimes happens that substantive nouns which express neither masculine nor feminine are referred to as of feminine gender when they end in  or

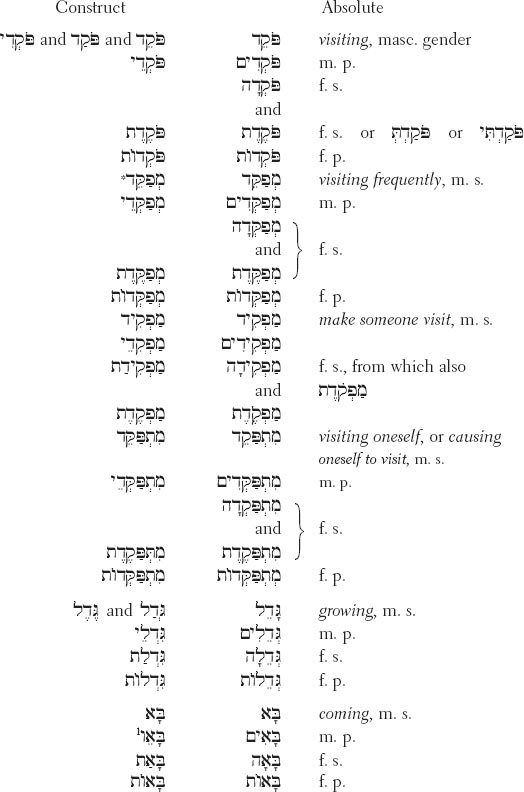

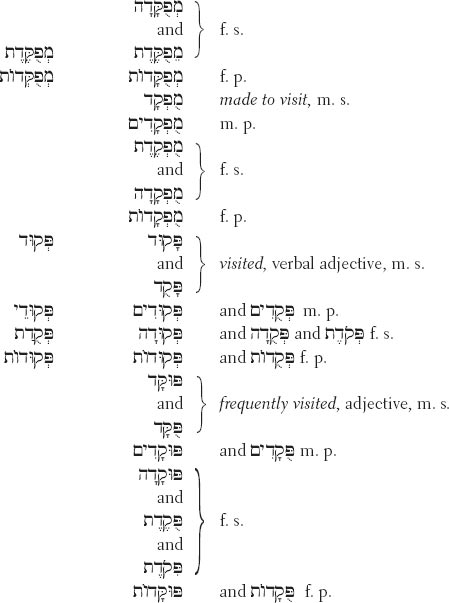

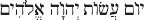

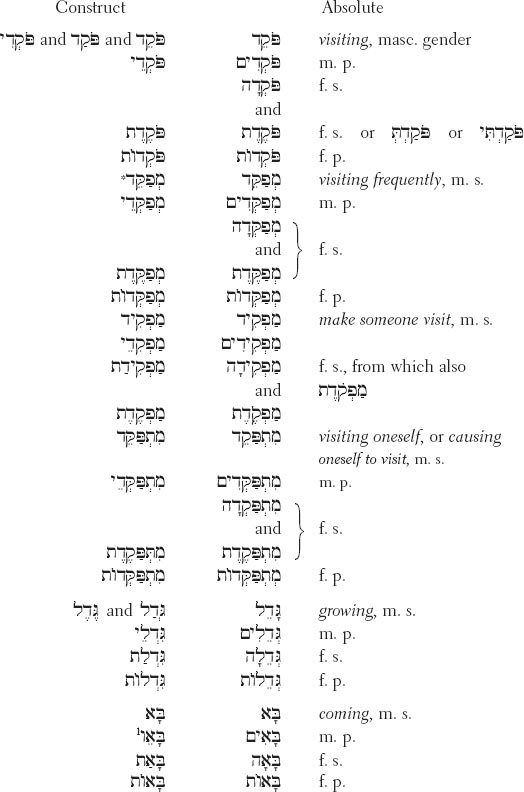

or  ; or perhaps this is (as we have said) because they derive their origin from feminine adjectives. But it is something else that I intend here: namely, that just as the determinations of the substantives originate from adjectives and participles, so the changes, which nouns experience in the construct case, derive their origin from mutations of infinitives and the participles. For all Hebrew nouns (as is known to all experts in this language) are derived from forms of verbs. It should be added that first and foremost the use of substantive nouns is to indicate something absolute and not relative. Indeed the latter is impossible for proper nouns; which thus are never found in construct case. But actions are seldom expressed without either an active or passive relationship, and, therefore, are rarely found in the absolute state. However it may be, the variations of the substantives are easily learned from the ways in which the infinitive and participial nouns vary. Thus there is no doubt that the one derives its origin from the other. I shall now list here a few examples and their variations in the construct case, as a model for the changes of all nouns, so that they may be easily committed to memory.

; or perhaps this is (as we have said) because they derive their origin from feminine adjectives. But it is something else that I intend here: namely, that just as the determinations of the substantives originate from adjectives and participles, so the changes, which nouns experience in the construct case, derive their origin from mutations of infinitives and the participles. For all Hebrew nouns (as is known to all experts in this language) are derived from forms of verbs. It should be added that first and foremost the use of substantive nouns is to indicate something absolute and not relative. Indeed the latter is impossible for proper nouns; which thus are never found in construct case. But actions are seldom expressed without either an active or passive relationship, and, therefore, are rarely found in the absolute state. However it may be, the variations of the substantives are easily learned from the ways in which the infinitive and participial nouns vary. Thus there is no doubt that the one derives its origin from the other. I shall now list here a few examples and their variations in the construct case, as a model for the changes of all nouns, so that they may be easily committed to memory.

Forms of Infinitives

These are the principal examples of the infinitives. And now I proceed toward the participles.

Forms of Participles

Active

But the reason that  , and others of this type are in construct

, and others of this type are in construct  , and

, and  , etc., is due to common usage of the language. We have already said above that a kametz before a segol replaces the first segol at the end of a sentence, or in the middle of a sentence to divide one part of it from the other, like

, etc., is due to common usage of the language. We have already said above that a kametz before a segol replaces the first segol at the end of a sentence, or in the middle of a sentence to divide one part of it from the other, like  for

for  and

and  for

for  . Therefore

. Therefore  , etc., occurs in the absolute state in place of the construct

, etc., occurs in the absolute state in place of the construct  .

.

But it should be noted that in this language it is mostly the custom to render the  vav quiescent, changing the syllable into a cholem; which is the most frequent usage and it is seen most prevalent in respect to this noun because in the Scriptures it is only once found in the construct, otherwise everywhere from

vav quiescent, changing the syllable into a cholem; which is the most frequent usage and it is seen most prevalent in respect to this noun because in the Scriptures it is only once found in the construct, otherwise everywhere from  fraud it is

fraud it is  and from

and from  wickedness

wickedness  ; and so in the rest of these forms.

; and so in the rest of these forms.

Finally, may I add something also about the ending of the plural. We see that the plural ending  is always retained in the construct; but

is always retained in the construct; but  loses the

loses the  and the chirek changes into a tsere. This pattern also holds true with the construct of dual

and the chirek changes into a tsere. This pattern also holds true with the construct of dual  , which similarly loses the

, which similarly loses the  with the chirek, and the patach changes to tsere, like from

with the chirek, and the patach changes to tsere, like from  eyes, it becomes

eyes, it becomes  in the construct state; and this I believe makes it that every patach before

in the construct state; and this I believe makes it that every patach before  with a chirek follows this form in the construct, making it from

with a chirek follows this form in the construct, making it from  a house

a house  and from

and from  wine

wine  , etc.

, etc.

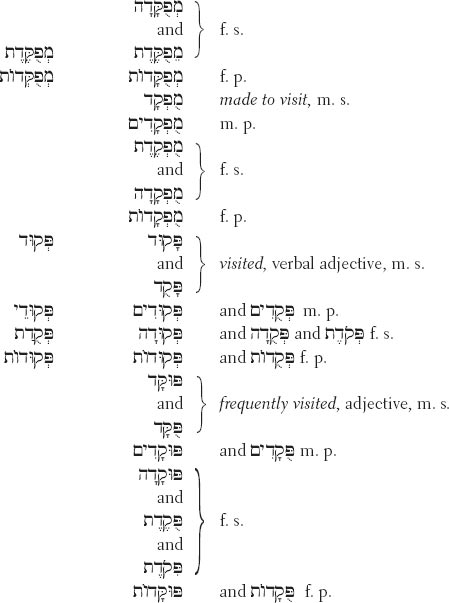

Now before I pass on to the last, I must first of all note that I understand by the word noun all classes of nouns. Every noun, except the proper noun (as we have already said), can be in genitive or can be changed to genitive; and particularly the relative form, or the preposition which is always indicated as relative, and on that account can almost always become a genitive, and is frequently changed; all of which I shall illustrate here very clearly by examples.

| House of God. Both are substantives. |

| A heart of a wise one. First is a substantive. The second adjective. |

|  |

|  |

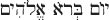

| The creation of God. First is an infinitive. |

| Day of the creation of God. Inf. which simultaneously modifies and is modified. |

| Early ones to rise, that is, those who are quick to rise. |

| Early in the morning, preposition in the genitive and participle in the construct. |

| Before the Lord. Preposition is construct from  before, so from before, so from  the midst, it is the midst, it is  in the midst of. in the midst of. |

| Until and until, that is, indefinite time, here the preposition modifies and is modified. |

| Plague without ceasing, that is, a plague which does not cease. Adverb is not modified. |

| Not wise; here the word  construct from construct from  is like in absolute state is like in absolute state  which like which like  changes in construct state, as we have said, from the patach and chirek into a tsere. changes in construct state, as we have said, from the patach and chirek into a tsere. |

preceded by a kametz or a cholem, change the

preceded by a kametz or a cholem, change the  into a

into a  and the kametz

and the kametz  into a patach -. Thus

into a patach -. Thus  becomes in construct case

becomes in construct case  , and means somebody’s prayer. So

, and means somebody’s prayer. So  to do becomes in construct case

to do becomes in construct case  somebody’s doing, as in

somebody’s doing, as in  the day of the Lord God’s doing.

the day of the Lord God’s doing. from

from  a word,

a word,  a talent of gold from

a talent of gold from  a talent,

a talent,  from

from  a wise man, as Job in chapter 9 called God

a wise man, as Job in chapter 9 called God  wise of heart. So

wise of heart. So  blessed,

blessed,  peace,

peace,  visiting,

visiting,  old, etc., change the penultimate kametz to a sheva; so also

old, etc., change the penultimate kametz to a sheva; so also  justice,

justice,  a blessing, change the ultimate kametz into a patach, and the penultimate into a sheva, and the

a blessing, change the ultimate kametz into a patach, and the penultimate into a sheva, and the  into a

into a  as we have already said, thus becoming

as we have already said, thus becoming  . It is only because two shevas cannot occur at the beginning of a word that the first sheva is changed into chirek. This is always the case, I cannot reiterate this too often, with every chirek and patach before a sheva.

. It is only because two shevas cannot occur at the beginning of a word that the first sheva is changed into chirek. This is always the case, I cannot reiterate this too often, with every chirek and patach before a sheva. from

from  hair, and

hair, and  from

from  a corner,

a corner,  from

from  an elder,

an elder,  from

from  a stick. But most frequently both the ultimate and the penultimate remain unchanged. Indeed, these and many others like them are completely uncertain; at times a noun changes the tsere and at times it retains it, which shows that in the Scriptures the dialects are mixed up. Thus everyone is at liberty either to change or to leave both the tsere and the kametz in the ultimate; except for the tsere before a

a stick. But most frequently both the ultimate and the penultimate remain unchanged. Indeed, these and many others like them are completely uncertain; at times a noun changes the tsere and at times it retains it, which shows that in the Scriptures the dialects are mixed up. Thus everyone is at liberty either to change or to leave both the tsere and the kametz in the ultimate; except for the tsere before a  which always should be retained because of common usage, like

which always should be retained because of common usage, like  a temple, for example. The word

a temple, for example. The word  occurs everywhere in the Scriptures in the construct case as

occurs everywhere in the Scriptures in the construct case as  , and

, and  and

and  become

become  and

and  . Therefore I say everyone is free to write

. Therefore I say everyone is free to write  for

for  and

and  for

for  , even though neither is found in the Scriptures. And what I have said about the tsere and the kametz should be said about everything that does not follow a fixed rule. But of this I shall treat copiously in another place. Here let me add a word concerning the matter of which I have spoken thus far, and which I regard to be no less essential toward the purpose of this chapter and toward the general knowledge of this language.

, even though neither is found in the Scriptures. And what I have said about the tsere and the kametz should be said about everything that does not follow a fixed rule. But of this I shall treat copiously in another place. Here let me add a word concerning the matter of which I have spoken thus far, and which I regard to be no less essential toward the purpose of this chapter and toward the general knowledge of this language. and

and  and the plural

and the plural  are characteristic of adjectives and participles, doubtless because the same noun may have an adjective, which sometimes is referred to as masculine and sometimes as feminine, and for that reason, at one time or another requires either of two endings. This is not the case with the substantive nouns and, therefore, it sometimes happens that substantive nouns which express neither masculine nor feminine are referred to as of feminine gender when they end in

are characteristic of adjectives and participles, doubtless because the same noun may have an adjective, which sometimes is referred to as masculine and sometimes as feminine, and for that reason, at one time or another requires either of two endings. This is not the case with the substantive nouns and, therefore, it sometimes happens that substantive nouns which express neither masculine nor feminine are referred to as of feminine gender when they end in  or

or  ; or perhaps this is (as we have said) because they derive their origin from feminine adjectives. But it is something else that I intend here: namely, that just as the determinations of the substantives originate from adjectives and participles, so the changes, which nouns experience in the construct case, derive their origin from mutations of infinitives and the participles. For all Hebrew nouns (as is known to all experts in this language) are derived from forms of verbs. It should be added that first and foremost the use of substantive nouns is to indicate something absolute and not relative. Indeed the latter is impossible for proper nouns; which thus are never found in construct case. But actions are seldom expressed without either an active or passive relationship, and, therefore, are rarely found in the absolute state. However it may be, the variations of the substantives are easily learned from the ways in which the infinitive and participial nouns vary. Thus there is no doubt that the one derives its origin from the other. I shall now list here a few examples and their variations in the construct case, as a model for the changes of all nouns, so that they may be easily committed to memory.

; or perhaps this is (as we have said) because they derive their origin from feminine adjectives. But it is something else that I intend here: namely, that just as the determinations of the substantives originate from adjectives and participles, so the changes, which nouns experience in the construct case, derive their origin from mutations of infinitives and the participles. For all Hebrew nouns (as is known to all experts in this language) are derived from forms of verbs. It should be added that first and foremost the use of substantive nouns is to indicate something absolute and not relative. Indeed the latter is impossible for proper nouns; which thus are never found in construct case. But actions are seldom expressed without either an active or passive relationship, and, therefore, are rarely found in the absolute state. However it may be, the variations of the substantives are easily learned from the ways in which the infinitive and participial nouns vary. Thus there is no doubt that the one derives its origin from the other. I shall now list here a few examples and their variations in the construct case, as a model for the changes of all nouns, so that they may be easily committed to memory.

writing,

writing,  a wolf, etc., a double segolate, patach, chirek, and sheva. A cholem is generally retained also but before a makaf we see that it is changed to a short o. The shurek very rarely or perhaps never is changed, and if occasionally a kibbutz is used in its place, it does not on that account become a construct, but because one may serve for the other; for a shurek is a vowel composed of a cholem and a kibbutz, and therefore, in place of a shurek we frequently see used either a cholem or a kibbutz.

a wolf, etc., a double segolate, patach, chirek, and sheva. A cholem is generally retained also but before a makaf we see that it is changed to a short o. The shurek very rarely or perhaps never is changed, and if occasionally a kibbutz is used in its place, it does not on that account become a construct, but because one may serve for the other; for a shurek is a vowel composed of a cholem and a kibbutz, and therefore, in place of a shurek we frequently see used either a cholem or a kibbutz. , and others of this type are in construct

, and others of this type are in construct  , and

, and  , etc., is due to common usage of the language. We have already said above that a kametz before a segol replaces the first segol at the end of a sentence, or in the middle of a sentence to divide one part of it from the other, like

, etc., is due to common usage of the language. We have already said above that a kametz before a segol replaces the first segol at the end of a sentence, or in the middle of a sentence to divide one part of it from the other, like  for

for  and

and  for

for  . Therefore

. Therefore  , etc., occurs in the absolute state in place of the construct

, etc., occurs in the absolute state in place of the construct  .

. vav quiescent, changing the syllable into a cholem; which is the most frequent usage and it is seen most prevalent in respect to this noun because in the Scriptures it is only once found in the construct, otherwise everywhere from

vav quiescent, changing the syllable into a cholem; which is the most frequent usage and it is seen most prevalent in respect to this noun because in the Scriptures it is only once found in the construct, otherwise everywhere from  fraud it is

fraud it is  and from

and from  wickedness

wickedness  ; and so in the rest of these forms.

; and so in the rest of these forms. is always retained in the construct; but

is always retained in the construct; but  loses the

loses the  and the chirek changes into a tsere. This pattern also holds true with the construct of dual

and the chirek changes into a tsere. This pattern also holds true with the construct of dual  , which similarly loses the

, which similarly loses the  with the chirek, and the patach changes to tsere, like from

with the chirek, and the patach changes to tsere, like from  eyes, it becomes

eyes, it becomes  in the construct state; and this I believe makes it that every patach before

in the construct state; and this I believe makes it that every patach before  with a chirek follows this form in the construct, making it from

with a chirek follows this form in the construct, making it from  a house

a house  and from

and from  wine

wine  , etc.

, etc.

before, so from

before, so from  the midst, it is

the midst, it is  in the midst of.

in the midst of.

construct from

construct from  is like in absolute state

is like in absolute state  which like

which like  changes in construct state, as we have said, from the patach and chirek into a tsere.

changes in construct state, as we have said, from the patach and chirek into a tsere.

to speak also means he has spoken;

to speak also means he has spoken;  to grow,

to grow,  to cook have the form of the perfect, as I have shown in its place. Therefore, I have no doubt that

to cook have the form of the perfect, as I have shown in its place. Therefore, I have no doubt that  with a double kametz and

with a double kametz and  with kametz and patach were also forms of the infinitive, from which form comes

with kametz and patach were also forms of the infinitive, from which form comes  in the construct, namely from

in the construct, namely from  , and

, and  . And let it suffice to note this in passing here because it is more extensively discussed under the subject of conjugations.

. And let it suffice to note this in passing here because it is more extensively discussed under the subject of conjugations. .—M.L.M.]

.—M.L.M.]