CHAPTER 5

WORKPLACE SAVINGS 3.0: FINDING THE KEYS TO RETIREMENT READINESS

Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.

The Pension Protection Act of 2006 actually worked better than many of us had expected. By offering official legislative and regulatory support for a series of best practices such as auto-enrollment or automatic savings escalation, the law significantly speeded the uptake of powerful, effective ideas that were already evolving in the retirement markets.

More importantly, its passage marked the moment when Congress and leading national policy makers began to treat workplace plans like the 401(k) as America’s primary retirement income source of the future. The new law’s key provisions, in turn, enabled those plans to take huge strides toward realizing their full potential.

Ten years later, the passage of the PPA looks increasingly like a transformative event. We have seen a host of dramatic, positive changes sweep across America’s workplace savings system. We have effectively proven a model for accumulating retirement assets. We have set many millions of workers on track to solve the challenge of reliably replacing their full work-life incomes for the rest of their days. We’ve taken great steps forward.

But as we will see, this success is still only partial and strictly limited to the accumulation side of retirement policy. We still need to provide workplace savings plans for tens of millions of workers who lack any payroll savings plan on the job. We even have a lot of work ahead to spread the best practices that PPA endorsed to all existing workplace plans. And the question of solving the distribution side of retirement policy—converting lifetime savings to reliable lifelong income—is a far thornier problem that we have just started to address.

Still, taking a quick look at how far we’ve come in the 10 years since the PPA’s passage should give us hope that we can, and will, solve these unmet challenges. After all, in the decade since the PPA, total U.S. workplace and IRA retirement savings have grown by a solid 6 percent per year (net of redemptions) despite the 2008–2009 global market crisis, ongoing financial stresses, and near-zero interest rates worldwide.

Across many metrics, from plan enrollment to guided investment choices to costs and fees, workplace savings plans have steadily improved. Here are just some of the changes we’ve seen in the PPA’s first decade, summed up in the Vanguard Group’s excellent annual survey, “How America Saves 2016” (Figure 5.1).

FIGURE 5.1 Highlights of “How America Saves 2016”—impact of PPA participant account management

Source: ©The Vanguard Group, Inc., 2016, used with permission.

- In 2006, only 12 percent of new employees had access to plans that automatically enrolled them. Today 63 percent of new hires are in plans that use automatic enrollment.

- In 2006, only 10 percent of plans offered auto-enrollment; today that number is 41 percent.

- In 2006, only 12 percent of plan participants were hired by companies whose plans offered professionally managed asset allocation strategies (target date or life-cycle funds, balanced funds, or managed accounts); today that number is 48 percent, and projected to be 68 percent by 2020.

- In 2006, only 43 percent of plans offered life-cycle funds; today that number is 90 percent.

- Today, plan participation rates are a robust 78 percent, with average deferral rates of 6.8 percent and median deferral rates of 5.9 percent.

Participant Contribution and Asset Allocation

These positive trends in basic plan design have been accompanied by significantly better investment choices by participants, often guided by their use of the plans’ own default investment options, blessed and sanctioned by the PPA.

Workplace savings plans that at the outset of the 401(k) era offered multiple, seemingly random investment options have since adopted much more effective strategies like target date funds or managed accounts that embed advice into the funds’ design and aim specifically to mitigate risk as retirement approaches.

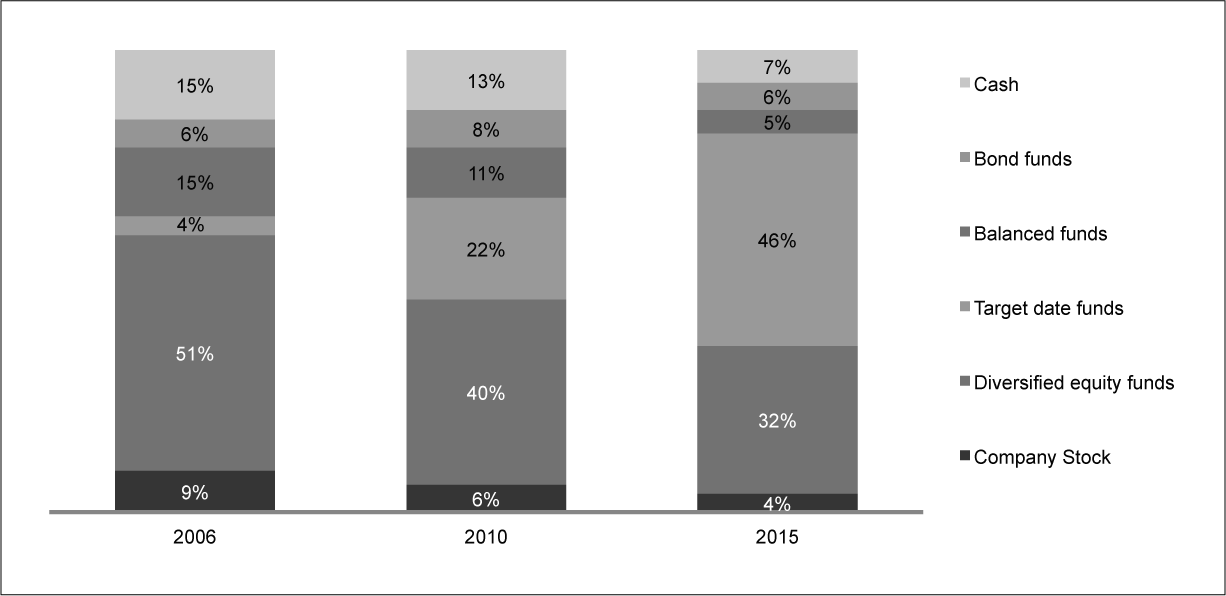

“How America Saves” also notes real improvements in workplace savers’ asset allocation:

- In 2006, investors had 15 percent of their allocations in cash; by 2015, this had been reduced to 7 percent.

- In 2006, plan savers held fully 9 percent of their retirement savings in company stock; today, that share has dropped to 4 percent.

- Contributions to target date funds have exploded, rising from just 4 percent of workplace plan contributions in 2006 to 46 percent by 2015, a rise of over 1,000 percent (Figure 5.2).

FIGURE 5.2 Highlights of “How America Saves 2016”—impact of PPA plan contribution allocation summary

Source: ©The Vanguard Group, Inc., 2016, used with permission.

One fundamental insight we can derive from seeing the impact of the auto-features endorsed by the PPA is that plan design itself determines both workplace savers’ choices and their results. What economists call framing or choice architecture heavily influences the choices that real working people actually make. So establishing the right framework for automatic decision making and providing guidance to well-designed default investment strategies can dramatically improve people’s chances of success.

Automatic plan design can, in fact, make success easy and failure hard.

That’s because inertia is the strongest single factor in workers’ saving behavior. It is near-universal. And smart plan design can make this force work for savers, and not against them.

Just a few years after the PPA gave automatic enrollment formal approval, for example, the percentage of plan sponsors adopting auto-enrollment for their workers more than tripled. What their experience now tells us is that roughly 90 percent of people who are auto-enrolled in workplace savings plans go with the flow and stay in; less than 10 percent opt out.

That kind of lift in workers’ participation rates vastly outpaces the gains in enrollment that companies spent millions of dollars to achieve through communications and investor education. And it requires major changes by plan sponsors who make the choice to go full auto in designing their plans.

The 3 Percent Glitch

The most serious error of too many plan designers, by far, is their tendency to offer initial savings deferral rates of 3 percent or even less, without any provision for automatically raising them. This single bureaucratic miscue, call it “the 3 percent glitch,” has had the perverse effect of taking a brilliant idea, automaticity, and causing it to actually undermine workers’ own best interests.

The origin of this misbegotten practice stems from the mention of 3 percent as a good starting point for workplace plans’ savings rates in one of the Treasury Department rulings in the late 1990s that authorized companies to adopt auto-enrollment. Too many plan sponsors took the mere mention of 3 percent savings rates as a guideline to follow, not just a place to start. Talk about unintended consequences!

Just last year, a decade after PPA’s passage, T. Rowe Price reported that over 38 percent of the plans they serve still enroll workers at an initial savings rate of just 3 percent. That’s better than nothing, of course. But the problem is that far too many workers auto-enrolled at 3 percent savings rates just stay there, obeying the most powerful force in retirement policy: inertia. That’s why the savings rates in auto-enrolled plans can actually be lower than those found in purely voluntary plans, where workers typically sign up to save 5 percent or more.

Some academics have perversely seized on this anomaly to claim that auto-enrollment itself is somehow inferior to purely voluntary plans. But the problem is not automaticity itself, it is the failure of some plan sponsors to adopt a fully automatic plan design package, including automatic savings escalation and guidance to dynamic default investments that automatically reduce the level of risk as retirement approaches, without workers having to make that decision on their own.

The 3 percent glitch, in other words, is caused by too little use of automatic plan design features, not too much. And there’s no doubt that low savings levels, like overly conservative investment choices, can have a corrosive long-term impact on retirement preparation. The truth is that we don’t serve anyone well by allowing them to believe that saving 3 percent or 5 percent or even 7 percent will be enough to enable them to finance a retirement income lasting 20 or 30 years or more.

For workers to take full advantage of market-based retirement savings, it is also critical to take age-appropriate levels of risk. Socking away savings in low-risk, low-return money market funds once did seem like a safe strategy for workplace savings plan design. Many first-generation 401(k) plans chose money market funds as a default. Today, we know better. Far from being safe, such strategies can be very dangerous if the goal is financing lifelong income.

In an age of persistently low interest rates, most “safe” investments virtually guarantee savings shortfalls over a long-term investment horizon. Even retirees need some investments that stand a chance of beating inflation. Retirement savers are all but obliged to invest some share of their savings in riskier assets like stocks. These may, indeed, be more volatile. But equities offer at least the chance of real long-term wealth appreciation. The opportunity costs of not owning them usually outweigh their risks.

Income Replacement: The Ratio That Defines Retirement Success

The ultimate goal of workplace savings, and the best measure of any retirement savings plan or system’s success, is its ability to amass enough wealth to ensure reliable income for life. So the best measure of retirement readiness shouldn’t focus on any absolute number, but on the income that retirement savings can generate, expressed as a percentage of what retirees earned while working.

Retirement planners call this the replacement ratio, which is calculated by simply dividing a retiree’s income by what he or she earned prior to retirement. For example, if a retiree who used to earn $100,000 a year is able to draw $50,000 a year in Social Security and private retirement income after retiring, then the replacement ratio is 50 percent.

There is no consensus among advisors, planners, or the retirement services industry on what the ideal replacement ratio is and whether workers should aim for 60 percent, 80 percent, or more. The answer varies widely among individuals, families, and different regions of the country. Perhaps the only consensus is that more is more, while anything close to or over 100 percent would be an unquestionable win, perhaps even a bit of an overshoot.

Empower Retirement’s Lifetime Income Score (LIS)

That’s why first Putnam Investments and now Empower Retirement, both companies that I lead, set out in 2010 to quantify working Americans’ ability to replace their income in retirement. We asked our research colleagues at Brightwork Partners to take account of all sources future retirees can draw on: Social Security, traditional pensions, workplace savings plans like 401(k)s, savings, insurance, home equity, and even ownership shares in a business.

We have since assessed the total assets of more than 4,000 working Americans aged 18 to 65 every year with a sample weighted to match U.S. census parameters. The resulting Lifetime Income Survey provides one of the most comprehensive assessments of potential retirement readiness in the country.

What’s more, we can also drill down into the LIS survey data to see how different subsets of workers are progressing toward the goal of income replacement. The survey thus gives us both a snapshot of where we stand 11 years after the PPA’s passage, and a guide to policy moves the country can make to radically improve all Americans’ prospects for retirement success.

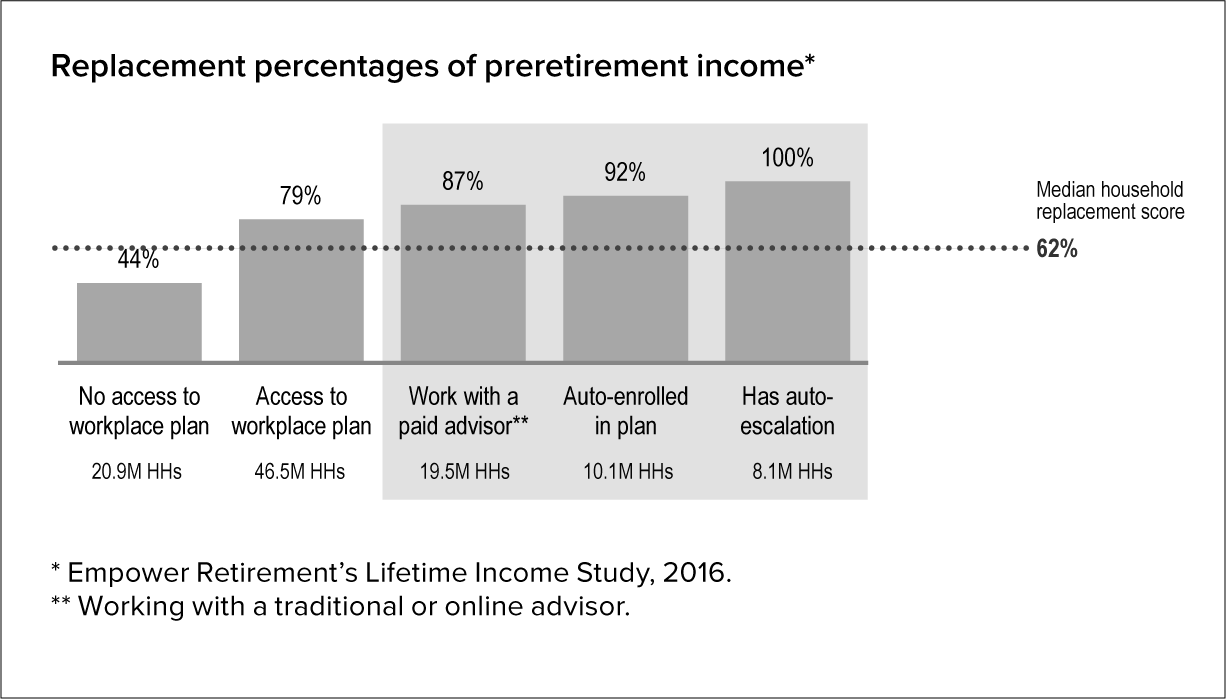

The sixth edition of the Lifetime Income Score Research, published in April 2016, found that, at the median, working Americans are on track overall to replace 62 percent of their working life income once they retire. (Median, of course, means that half the population will be able to replace more than 62 percent, while half the people will be able to replace less.) The survey also discloses major differences in replacement rates among different groups of workers. In effect, it gives us an x-ray of a very clear hierarchy of best practices in workplace plan design that help increase retirement readiness. Let’s look first at the overall picture, and then tease out some critical variables. Figure 5.3 gives an overall view of how American households are faring in terms of retirement readiness a decade after the Pension Protection Act of 2006.

FIGURE 5.3 Where we are now: six states of retirement readiness in America

Source: Empower Retirement LIS VI.

A look at Figure 5.4 shows that lack of access itself is the system’s single most acute shortfall, with nearly 21 million households having no savings plan at work. These workers are on track to replace just 44 percent of their preretirement income, even including Social Security. In fact, having access to some form of workplace payroll deduction lifts prospective replacement ratios by fully 35 percent—from 44 percent to 79 percent, the single biggest leap in this series.

FIGURE 5.4 Why closing the “coverage gap” is so vital

Source: Empower Retirement LIS VI.

Those with no workplace savings plan—42 million of our fellow Americans—are likely to face a sharp drop in living standards in retirement, perhaps outright poverty. Acting to close this coverage gap is the single most powerful move we could make to raise savings and improve retirement readiness in America. The coverage gap effectively defines the crossroads of wise savings policy and basic decency.

A series of other key enhancements to workplace savings plan design do much to further lift workers’ prospects of full retirement readiness. Having access to a paid financial advisor lifts income replacement to a median level of 87 percent (Figure 5.5). (See box, “The Value of Advice.”) Workers in plans that automatically enroll them and automatically escalate their savings from the initial rate are on track to secure 92 percent and 100 percent replacement rates respectively. Even bearing in mind that these are median results, they are impressive gains, driven very clearly by workplace savings plan design itself.

FIGURE 5.5 Three key enhancements to workplace plan design

Source: Empower Retirement LIS VI.

The most powerful variable of all is simple: More is more. Workers in plans who have achieved savings rates of 10 percent or more are on track at the median to replace fully 117 percent of their work-life income. This is success by any reasonable measure, and it’s important to note that it is not driven wholly by higher incomes. That’s not to say there isn’t a greater tendency and ability for high-income workers to save more. But income is not the whole story.

The key driver is actually the choice architecture and the behavioral “nudges” that plan design itself creates. LIS data clearly show that workers across the income spectrum can and do achieve high levels of retirement readiness if their workplace plans adopt “full auto” plan design and escalate to savings rates of 10 percent—or more (Figure 5.6). Plan design and absolute savings rates are the prime variables determining success.

FIGURE 5.6 The dominant variable: higher savings rates

Source: Empower Retirement LIS VI.

That’s why most experts, myself included, advocate automatic enrollment at a minimum of 6 percent of salary, escalating steadily within two years or so to 10 percent or more. So I am pleased to see more plan sponsors moving to this higher level. This is also why the Financial Services Roundtable, one of the nation’s leading advocates for retirement savings, sponsors a national campaign called “Save 10” that aims to make 10 percent or more the national norm for all workplace savings plans.

Since America’s workplace savings plans average roughly a 7 percent savings rate today, moving it up to 10 percent or more may seem like a modest goal. But it’s actually very ambitious. What “Save 10” calls for is a rise in workplace savings of over 40 percent, across thousands of existing workplace plans and by tens of millions of retirement savers. It is a very big deal.

Looking over the Horizon: Toward Workplace 4.0

We can usefully think of the decade after the Pension Protection Act of 2006 as Workplace Savings 3.0, the third generation in the evolution of workplace savings in America. This period has been marked by the widespread, but not universal, adoption of the best practices to which the PPA gave solid legal sanction: automatic enrollment, automatic savings escalation, and guidance to proven default investments, all of which are plan design features more likely to take workers to full retirement readiness.

The gains scored, both in raw savings accumulated and in insights into what works, have been profound. LIS data show, for example, that more than 28 million households—those that enjoy automatic savings plans and high deferrals—are on track at the median to replace over 92 percent of their income in retirement. This is not an anomalous outlier—it’s 56 million people!

Their success is proof positive of something I’ve said for many years: “There is nothing wrong with the 401(k) system that can’t be fixed by what’s right with the 401(k).” In fact, I would argue that the insights we’ve gained about the plan design elements that make for success may be the greatest achievements of the post-PPA decade. The challenge is to get from insight to implementation. And that’s not going to be easy.

Huge gaps in our retirement system still remain. As we’ve seen, tens of millions of American workers have no access to savings plans on the job. And even after a decade, and despite the very powerful evidence of how auto-plan design actually works, far too many companies have yet to go full auto in their plan designs or lift their savings goals to 10 percent or more. It is as though we had discovered a vaccine against a debilitating ailment, in this case elderly poverty, but only vaccinated half our population.

Still, the PPA was a qualitative leap forward for workplace savings in America. The successful outcomes it is delivering for millions point the way toward making such successes available to all. What this vast experiment tells us is that we have essentially solved the challenge of accumulation. We now know that with full auto plan designs and deferrals over 10 percent, virtually all workers can build up enough assets to supplement Social Security and achieve reliable lifetime incomes.

The challenge now is to cover all workers and spread proven best practices across all workplace plans—not just large companies and forward-thinking small ones. That will likely require some fresh legislative and regulatory nudges for plan participants.

There is, however, positive ferment in the marketplace. America’s workplace retirement system is, as always, in dynamic flux. Just as new solutions like target date funds and auto-enrollment were gestating in the early 2000s, today the industry is developing approaches for dealing with the single most glaring challenge that PPA didn’t touch: the solutions and strategies to convert life savings into lifelong income.

Clearly, the main unfinished business of the second post-PPA decade will be to go beyond accumulation to find workable solutions for the far more complex, and individualized, goal of lifetime income distribution. Lifetime income solutions, in plans and beyond, strike me as the holy grail of the next generation of workplace savings in America. Done right, this could enable DC plans to match, or even surpass, the reliable incomes that traditional pensions once provided.

Fortunately, more plan sponsors and retirement providers are already experimenting with a wide variety of insured income solutions including annuities, partial annuities, deferred annuities, and non-annuity guaranteed income products beyond workplace plans and into retirement. And just as the U.S. Treasury helped spur automatic enrollment by giving it legal sanction in the late 1990s, Treasury has now given a green light for the inclusion of deferred annuities directly in workplace plans and in IRAs.

The good news, then, is that this next generation of retirement solutions—Workplace Savings 4.0—is busy being born right now in the marketplace. I believe that it should soon be helped along and ratified by regulatory and legislative action that builds on what the PPA achieved and takes workplace savings in America to a new and higher level.