The quality and training of the dog

The quality and training of the dogSHEEP HAVE A RELATIVELY STRONG DESIRE to group together in response to a threat, real or perceived, and that trait makes them well suited to being worked with dogs. How useful a dog can be to a shepherd depends on many things, especially these:

The quality and training of the dog

The quality and training of the dog

The suitability of the farm to a working dog: for example, how paddocks, fencing, and handling facilities are arranged

The suitability of the farm to a working dog: for example, how paddocks, fencing, and handling facilities are arranged

The shepherd’s understanding of the dog’s ability

The shepherd’s understanding of the dog’s ability

Most important, the shepherd’s willingness to work with a dog

Most important, the shepherd’s willingness to work with a dog

A well-trained stock dog can be an enormous help to you as a shepherd. It can greatly reduce the amount of equipment required for sheep handling. The dog can drive stock from one pasture to another, load one sheep (or hundreds) into corrals or stock trailers, or work with you as you operate a squeeze chute for pregnancy checking, shearing, or worming. A good dog can single out one animal without moving the entire flock to a sorting facility. During lambing, it can help bring in expectant mothers. A herding dog can also help you count your livestock by filtering them along a fence, and help you at feeding time by keeping them away from the feeders while you’re spreading grain or hay. And you will truly know the value of a herding dog when it comes to escaped sheep — it regathers them easily, whereas without a dog you could have serious trouble capturing the wayward sheep. In short, a good stock dog can be more help than several human helpers, as the effect of the dog on the stock and its physical abilities differ greatly from those of a person and are generally more useful than a second pair of hands.

While some herding dogs may act to a certain extent to protect their sheep, they should not be expected to function as livestock guardian dogs. (See chapter 5 for more about guardian dogs.) In fact, a herding dog shouldn’t be left unsupervised with the sheep. Because it’s been bred and trained to move and control stock, if left unsupervised, the dog most likely will not allow the flock to remain “uncontrolled” for long. This is especially true of young herding dogs, which need very close supervision. Luckily, as most herding dogs mature, they learn when their intervention is required and when they are “off duty.”

A well-trained, well-bred dog allows one person to manage a very large flock with minimal physical effort and aggravation, but any dog — trained or not — that has the respect of the sheep may be of some use in the management of a flock. For example, an untrained dog, regardless of breed, that barks and chases after the sheep can still be of some assistance in pushing them into chutes or squeeze gates but may need to be restrained on a leash.

With some training, almost any dog that has a desire to “go after the sheep” can be taught to be of assistance in moving sheep around. However, a non-herding breed of dog thus encouraged to go after the sheep must be carefully watched. Such a dog, unrestrained by hundreds of years of selective breeding, may be motivated solely by a predatory instinct and could become a threat to the sheep. Indeed, any dog that’s encouraged to work the sheep has been given permission by the owner to interact with them and should be supervised or restrained when not working. In many breeds, there is very little separation among the instincts to chase and play, hunt the livestock, and herd the livestock.

The amount of assistance the dog provides the shepherd is determined by the natural ability of the dog to work livestock and how well it has been trained. When buying a dog to work livestock, the best policy is to buy one from bloodlines of the breed most often used in your area for herding.

Many of the traditional herding breeds are now most often bred for the show ring or as pets, which has resulted in a loss of herding qualities in some of these breeds. Fortunately, there is a great deal of renewed interest in working dogs, and some fine trainers are again focusing attention on the working qualities that these dogs were developed for. That is exciting! A good resource for learning more about all the breeds that are used as herding dogs is the American Herding Breed Association. The group also sponsors trials for herding dogs around the country. See pages 409–410 for other excellent resources.

Herding breeds are often divided into three very general types: gathering dogs, tending dogs, and driving dogs. Any good herding dog, regardless of the type, should be able to do all of the herding-related work on a farm; that is, gathering dogs should be able to drive, and driving and tending breeds should be able to gather.

Dogs such as the Border collie, originally bred to work in wide spaces, are considered gathering dogs. These dogs were bred to gather semiwild sheep off large, open pastures. While the Border collie is currently the preeminent gathering breed in North America, there are also some excellent kelpies bred in Australia and the United States that are still working. In sum, gathering-dog breeds are the following:

Australian shepherd

Australian shepherd

Bearded collie

Bearded collie

Border collie

Border collie

Collie

Collie

Kelpie

Kelpie

Dogs that are considered tending breeds are those that were developed in Europe to help in the grazing of sheep in areas around crops. Dogs of this type customarily took their sheep out to graze each day and then patrolled along the grazing area to keep the sheep restricted to the unfenced space that they were supposed to graze. The following are considered tending breeds:

Beauceron Pyrenean shepherd

Beauceron Pyrenean shepherd

Belgian Malinois

Belgian Malinois

Beauceron Pyrenean Shepherd

Belgian Tervuren

Belgian Tervuren

Bouvier des Flandres

Bouvier des Flandres

Briard

Briard

German shepherd

German shepherd

Puli

Puli

The breeds that are now known as driving breeds were originally developed to help drovers move sheep to market along open lanes or for use in stockyards. The New Zealand Huntaway is a driving breed that’s used today in New Zealand to drive very large flocks of sheep by barking and moving back and forth behind the sheep. Other common breeds of this type are:

Australian cattle dog

Australian cattle dog

Old English sheepdog

Old English sheepdog

Rottweiler

Rottweiler

Welsh corgi (Cardigan or Pembroke)

Welsh corgi (Cardigan or Pembroke)

There are two basic approaches for obtaining a herding dog: start with a puppy or buy a mature, trained dog. The puppy route is, of course, less expensive up front, but the puppy won’t be ready to work for quite some time, will require intensive training, and may never work out well. By purchasing a mature, trained dog, you can be sure that the dog knows its stuff, but be prepared to pay a significantly higher price for a trained dog than for a puppy.

When you are selecting a puppy as a future working dog, it’s impossible to assess its natural herding ability. Thus, choosing a puppy is really a process of selecting the parents that are most likely to produce a puppy that suits your special needs.

In selecting the parents, your primary consideration should be given to their working ability. Both parents should be seen working the type of stock that the puppy will be expected to handle. At the very least, both parents should be able to do the following:

Gather a group of sheep a few hundred yards away from the shepherd and fetch them to the shepherd in a quiet, controlled manner

Gather a group of sheep a few hundred yards away from the shepherd and fetch them to the shepherd in a quiet, controlled manner

Hold the sheep in a group for the shepherd

Hold the sheep in a group for the shepherd

Single out an individual sheep and control it without the use of force or excessive aggression

Single out an individual sheep and control it without the use of force or excessive aggression

Move the sheep without difficulty or the use of force

Move the sheep without difficulty or the use of force

Demonstrate their ability to move the sheep in the way that would be appropriate for ewes during their last weeks of pregnancy — gently but firmly

Demonstrate their ability to move the sheep in the way that would be appropriate for ewes during their last weeks of pregnancy — gently but firmly

The prospective buyer should interview the dog breeder to learn about his or her breeding program. Learn what traits are being bred for and what type of puppy the breeder hopes to produce. While breeders cannot guarantee the herding qualities of the pups they produce, they can at least discuss why they have bred two particular dogs and how they hope the puppies will turn out. There are plenty of top working dogs around; don’t settle for a puppy whose parents don’t demonstrate the qualities you require.

It is important to feel comfortable with the breeder; he or she should be willing to provide the names of prior customers and inform the buyer how previous puppies have performed.

Both parents of the puppy should have had their hips X-rayed to determine if they have canine hip dysplasia and ideally should have a rating of their hips from the Orthopedic Foundation of America. Dogs with any sign of hip dysplasia should not be bred. Both parents should also have had their eyes examined by a veterinary ophthalmologist and have been certified as clear of progressive retina atrophy (PRA) and collie eye anomaly (CEA). Both of these conditions are hereditary eye disorders that can lead to some sight loss and even blindness. Only a veterinary ophthalmologist can determine that a dog is free of these disorders.

Always keep these health concerns in mind when selecting a puppy. Regardless of a dog’s talents, it is useless if it is physically unable to perform the job for which it was bred.

Initially, puppies should be taught good manners: to come when called, to walk on a leash, and to lie down on command. Formal, herding training can’t start until the dog “begins to work,” or “turns on to sheep.” Most well-bred herding dogs begin to show a desire to work sheep between 8 weeks and 12 months of age, but it’s important not to leave a puppy unsupervised with the sheep. The puppy could be hurt by the sheep, or the sheep could be hurt by the puppy; it could also learn bad habits by working unsupervised. The best age to start formal training is usually between 10 and 12 months because the first instinct exhibited is the desire to get to the head of the flock and turn back the escaping sheep, but this can be hard to accomplish until the puppy is fast enough to catch the sheep. Dogs that begin training before they can outrun the sheep quickly learn to chase them rather than to try to turn them back to the shepherd — a very bad habit indeed.

If the shepherd plans to do anything with the dog other than just let it chase the sheep, then the dog is going to need to develop instincts for tactics beyond chasing. The quality of the other instincts and the cleverness of the trainer ultimately determine the quality of the dog.

Once the young dog begins to work the sheep, he should be encouraged to keep them in a group. This is also a good chance for the shepherd to help the dog “break” the sheep. The sheep need to learn to respect the dog and learn to move away from it. Young pups that don’t know how the sheep are supposed to respond may require your help to move the sheep along — at least until they get the idea of what’s required. This is especially true if you’re also using “unbroken” sheep that don’t know how to respond to a dog. If possible, train the pup with a flock that’s used to being worked by a dog. But if you’re locked into the combination of a new pup and unbroken sheep, the best solution may be to ask a friend or acquaintance with a mature working dog to come over and help break the sheep for the new dog. If help is not available, take 10 or 15 young sheep, put them in a small pen, and use them for the beginning training of the pup.

Once these early, basic lessons are learned, it’s time to move on to directional commands, the outrun, and driving. All of the dog’s training should be done with the dog and the sheep close to the shepherd. Once lessons are learned, they can be perfected at greater and greater distances from the shepherd.

It is important not to expect too much from the young dog at the beginning of training. Allow him to gain confidence in his ability before expecting him to move difficult sheep. Patience at the beginning of training will be more than repaid at the end with a powerful dog that can walk up to any sheep and be confident that the sheep will move away.

A well-bred herding dog should learn the early lessons quickly, and by the time the dog is 12 or 13 months old, it should already be a useful helper on the farm. Remember, though, the dog is young — be ready to offer assistance as needed until all the jobs are learned and the dog has matured.

There are many expert trainers of stock dogs who offer lessons and clinics to assist beginners in training their dogs. It is possible to attend such lessons almost anywhere in the United States as either a student or an observer. A few such lessons are usually a big help for shepherds with their first dogs.

There are always trained dogs available for sale. The level of training varies from “started” to “fully finished.”

A started dog will generally gather sheep at about 200 yards (182.8 m) and bring them to the handler, requiring few commands to do so. The dog will stop on command and walk up to the sheep on command.

A dog that is fully trained to the “open level” of trials (competitions) should be capable of placing “in the money” at an open trial of 50 to 60 dogs. Such a dog is able to gather sheep at any distance (in some cases up to half a mile [0.8 km] away). The dog should be able to drive sheep in a controlled manner several hundred yards away from the handler. A fully trained dog should also be able to shed and control a single sheep.

The prices of started and trained dogs vary according to the quality of the dog, the level of training, and the part of the country. Dog trials are excellent places to inquire about available trained dogs and to see the actual work of the dogs that are for sale.

During the late nineteenth century, sheepdog trials became a popular activity among European shepherds and farmers. The trials in the British Isles developed quite a bit differently from those in Europe. Most dog trials in the United States are based on the British model.

While many excellent stock dogs never compete in sheepdog trials, such trials remain an excellent place to see a variety of dogs at work and to learn more about the breeds from the handlers and breeders who frequent competitions. A good trial will show off a variety of dogs with different styles of working and different levels of training.

Most regions of North America have organizations that host competitions. In addition to Border collie trials, there are now sheepdog trials for other herding breeds and multibreed trials. Some of the bigger annual trials that are definitely worth the travel are the Bluegrass Classic, held in May in Lexington, Kentucky; the Meeker Classic, held in Meeker, Colorado, in September; and the Soldier Hollow Classic, held at Utah’s Soldier Hollow Resort on Labor Day weekend. The National Finals moves around the country each year, with the top 150 dogs from other sanctioned trials competing for the top recognition. And if you are really up for a trip, the World Sheepdog Trials are held at different locations every year in the United Kingdom in September.

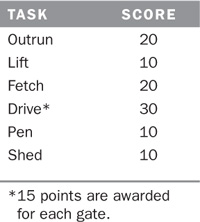

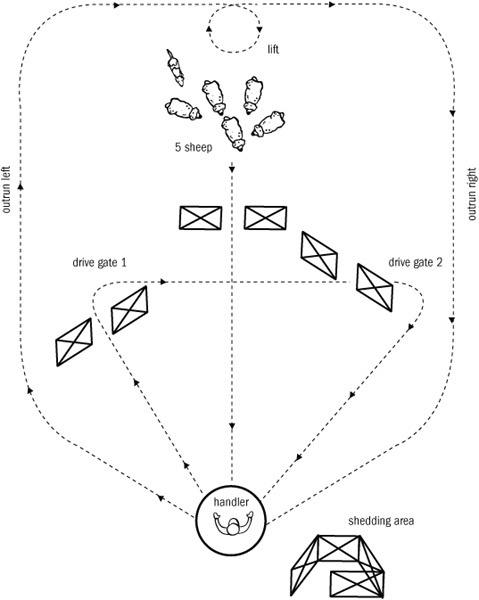

INTERNATIONAL SHEEPDOG TRIAL SCORING DIAGRAM

SCORING