Chapter 7

Temptation and transgression

“Well, it hardly matters what kind of joke we’re talking about, I think jokes in general are all equally funny”, Huibert Busser, a forty-two-year-old human resource manager I had met at Moppentoppers, told me. “But I’ve given it a bit of thought. What is a really good joke? What’s required for it to be good? It’s - at least what I think, but that’s only me - that it has to hold the attention of the person listening from beginning to end. And there has to be an unexpected twist in it somewhere. The best jokes are like that. If you could find a joke like that that didn’t offend any group and that on top of that wasn’t sexist, then you’d have a world-class joke. Those are the cleverest of all. Clean jokes that catch the attention and don’t let go from A to Z, and that you can tell in an interesting way too.”

The question Busser is asking himself here - what is needed for a good joke - is the main theme of this chapter: what is a good or a bad joke? Do people have the same criteria for this or are there differences in taste? What we are talking about here, therefore, are taste differences within the genre.

In the previous chapters, we have encountered some factors that play a role in the appreciation of not only genres and styles but also individual jokes. One important factor is the extent to which a joke is concerned with a senstive topic. In general, a joke is seen as funny if it touches upon a social boundary; but when this goes too far, appreciation for the joke quickly fades.25 Opinions as to what goes too far or not far enough to be funny, differ markedly. Moreover, as we saw in Chapters 4 and 5, transgressing a boundary is not appreciated by everyone in the same way: “hard” or “coarse” jokes are valued more positively by people with the intellectual and youthful humor styles than by older people or people who like popular humor.

The appreciation of individual jokes is also determined by the extent to which people identify with the content or intent of a joke. In humor that reflects a worldview, such as satire or political humor, identification is of prime importance. However, identification also significantly affects the appreciation of other forms of humor.26 For instance, while a good ethnic joke has the potential to amuse anyone, they are more fun for people who - secretly or openly - agree with their intent. A lack of points to identify with works against a joke: an anecdote you do not agree with, or in which you do not recognize your own situation or standpoint, quickly becomes unfunny. The outspoken masculine perspective of sexual jokes makes it more difficult for women to like them (Abrams and Bippus 2011; Greenwood and Isbell 2002; Herzog 1999).27

Identification and transgressiveness are related to the content of a joke. Both mechanisms are well-explored in psychological studies of humor appreciation, where they are usually explained in terms of personality characteristics (cf. Ruch 1998; Martin 2007). In addition to these factors of content, jokes vary in form. Even within the rather uniform and standardized genre of the joke, variations exist in the structure of the joke and the “joke technique”, from the build-up to the punch line.

Humorous form and technique has been most extensively theorized by linguists and literary scholars, who usually have little interest in people’s responses or variations in appreciation. Some psychologists, most notably Willibald Ruch (e.g. 1988, 1996, 1998; Carretero-Dios and Ruch 2010; Ruch and Forabosco 1996; Ruch and Malcherek 2009), have studied the relationship between personality and the appreciation of humorous form. Generally these studies use a wider variety of humorous genres (as I have in the American study reported later in this book). It is easier to see how boundary transgressions and possibilities for identification will influence appreciation, than to predict how form or technique affects the liking of a joke.28 This chapter attempts to connect variations in both content and form of jokes with differences in their appreciation.

The question of differences in the joke’s form is connected with the question of quality differences among jokes. Quality, in all cultural genres, from high to low, is sooner sought in form – technique, delivery, style - than in content. In addition to the way good storytellers deliver a joke, joke tellers sing the praises of the “real find” and the “masterful build-up”. Busser, too, concludes that the form of the joke determines its quality. The best jokes “hold the attention from beginning to end” thanks to the delivery or to an unexpected twist. Asking how differences in the appreciation of separate jokes arise easily leads to the question what constitutes a good joke and how this distinguishes it from a bad one.

The balance between funny and offensive

During the interviews with joke tellers I asked them to explain what a good joke is. They usually proceeded to tell me what was not good: namely, hurtful or coarse jokes.

And what sort of jokes do you like?

You know, dry humor. Humor that’s not coarse. Not discriminating. Not hurtful. And not too racy. But funny. You want to know what I really hate? Humor and jokes about illness. Or about Belgium and Dutch people. And I don’t tell racist or discriminating jokes either, or about certain diseases.

(Matthieu Cnoops, 24, welder)

Getting back to jokes, what kind of jokes do you like?

Me? Well, that’s hard to say. I don’t like dirty jokes. Or coarse jokes.

(Jacob Hitters, 53, draughtsman).

So I always tend to tell ordinary jokes, just plain funny ones.

And what do you mean when you say, just plain funny?

Well, what I... I really think people’re stupid, you know, if they make fun of the disabled or people who’re really seriously ill or something like that. I don’t like that much. That’s not my thing. Take for instance the case, you know Dutroux, that’s going on right now. Now that’s something really serious, I think it’s really terrible what he was up to... So I think those are really stupid jokes, totally beside the point. And yeah. Jokes I like are jokes that are a bit appetizing, you know. About Sam and Moos and well, little delicious things that just link up.

(Chantal Wijntuin, 45, social worker)

Joke tellers drew clear boundaries between jokes that “can be told” and that “go too far”, often in remarkably similar terms. They marked the same boundaries, employed the same rules, and phrased their arguments, protestations, escape routes and ways of stating exceptions to the rules in similar ways. There was considerable agreement, moreover, between compilers of joke books, editors of Moppentoppers, and what the joke tellers told me. Everyone involved in Dutch joke culture, in other words, shares a discourse about jokes and boundaries. Within this discourse, the same statements are reiterated again and again about the connection between humor and boundary transgressions: a joke that is hurtful or at the expense of others goes too far, and is no longer funny.

A good joke requires a fine balance between funniness and transgression. To explore the relationship between appreciation and transgression, I turn again to the ratings of the jokes discussed in Chapter 3. The questionnaire results show the negative effect of (strong) boundary transgression on joke appreciation. Respondents were asked not only to indicate how funny each separate joke was but also how offensive or coarse they thought it to be.29 The correlation between (aggregated) funniness and offensiveness turned out to be -.44 (p < .01). Overall, the coarser the joke was thought to be, the less it was appreciated.

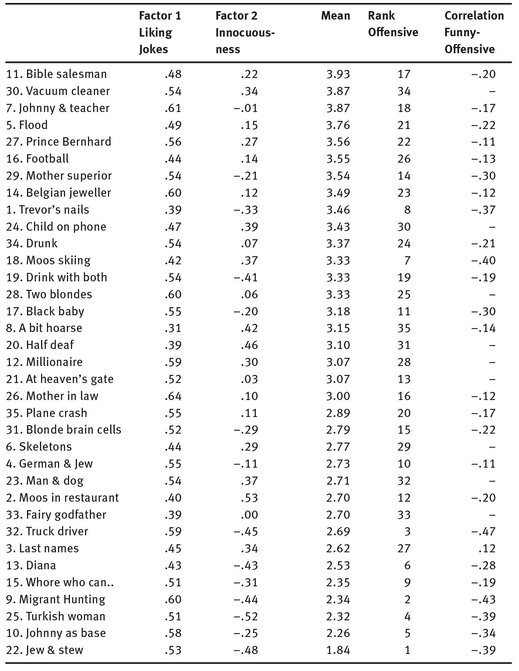

Many of the individual jokes also showed a negative correlation between funniness and offensiveness. Table 5 shows the factor loadings for the factor analysis of joke appreciation that was discussed in Chapter 3. The first factor I interpreted as a general factor for “joke appreciation”, correlating both with gender and class background. The second factor has to do with innocuousness (positive loadings) versus offensiveness (negative loadings). The jokes with negative loadings generally have a negative correlation between funniness and offensiveness. Moreover, they tend to be at the bottom of the ranking: they were, overall, not very well liked.

As Table 5 shows, the connection between funniness and offensiveness is most pronounced in extreme cases: jokes so offensive that they are hardly liked at all. These jokes go too far for almost everyone. They include explicit ethnic jokes like the following two:

What’s the difference between a Jew and a stew?

A stew doesn’t scream when it’s put in the oven.

I’m walking with a friend around the red-light district in Amsterdam and all of a sudden he shoots three black men dead. I say: “What’re you doing?” He says: “I’ve got an MHL, a migrant hunting license.” So I buy one too. A week later, we’re walking in a notorious neighborhood in The Hague and I shoot five niggers. Along comes a police officer and says: “What do you think you’re doing?” “I’ve got an MHL.” The police officer says: “Yeah but that covers the cities, not the reservations.”

These jokes were appreciated very little indeed: they were placed last and fourth last, respectively, in the order of appreciation. In these, the level of boundary transgression was too high, at least for a written questionnaire. There are circumstances under which such jokes are shown to better advantage, and then the balance between funniness and coarseness could tip to favor the joke. However, jokes that were not offensive at all were not necessarily rated highly either. Although one of the least offensive jokes ranked second, the other jokes that were generally regarded as very inoffensive - mostly absurd jokes or wordplay - received mediocre ratings overall.

The jokes that were liked best were medium-coarse: neither the most nor the least offensive. These jokes touched on a boundary but did not transgress it. The balance between funny and coarse was then (for the average respondent) just right. One joke that satisfied this demand for medium coarseness has already been cited (“Wwwwould you llllike to bbbbuy a bbbible ? Or ssshall Irrrread it ttttto you?”). On average, this joke was appreciated the most and was placed precisely in the middle of the scale of coarseness (18th). The joke that placed one step further on the scale of coarseness (19th), is also an example of such a well proportioned joke:

A primary school teacher promises a surprise to the pupil who solves the riddle. Her first riddle is: it walks around on a farm, it’s spotted and it gives milk. Johnny puts up his hand and says: “A cow.” The teacher says: “That’s good, but I meant a goat.”

Her next riddle is: “It walks around on a farm, it’s got feathers and it lays eggs.” Johnny tries again, saying: “A chicken.” The teacher says: “That’s good, but I meant a goose.”

Johnny’s pretty sick of this by now and he says he’s got a riddle for his teacher. He says: “It’s hard and dry when you put it in your mouth and it comes back out all soft and damp.” The teacher turns red and Johnny says: “That’s good, but I meant chewing gum.”

Table 5 illustrates the negative effects of extreme transgression, but also a general positive effect of milder boundary transgression. This depends somewhat on the topic of the jokes. While jokes about religion (Trevor’s nails, Mother Superior) can be deemed offensive and still liked, this is less likely for ethnic or sick jokes. Thus, a light or medium boundary transgression usually enhances the amusement value of a joke.

The positive effect of transgression is most obvious from the one joke on the questionnaire that achieved a positive connection between coarseness and funniness:

Madonna doesn’t have one; the pope has one but doesn’t use it. Bush has a short one and Wolfowitch a long one. What is it? A last name.30

This jocular reference to something that perhaps still counts as a taboo subject for some, is mild by contemporary criteria. Generally, it was neither thought very funny nor offensive. However, the positive correlation shows that people who saw a boundary transgression in this joke liked it better than people for whom this joke did not even approach a boundary.

Table 5: Appreciation and offensiveness of the jokes in the questionnaire:

Factor loadings31, average appreciation, rank order for offensiveness, and correlation between funniness and offensiveness.

Varying viewpoints on offensiveness

There was a broad spread in judgments of offensiveness: some jokes were not found to be offensive at all while others were seen as extremely coarse. There were also large differences between respondents. Suprisingly, differences of opinion about offensiveness were larger than those about funniness. The variation was lowest for the most offensive jokes. The coarser a joke, the more people agree that it is coarse.

Generally, older people were more easily offended by jokes than younger people, as the .42 correlation between the “innocuousness” factor and age underlines. The previous chapter described the hardening of the humor. As a consequence of this historical shift, people of different age groups have grown up with different standards of offensiveness. Contrary to expectation, women were not significantly more sensitive than men in this respect. On average, they did not rate the jokes as more offensive. Also, the innocuousness factor showed no gender relationship.

Table 6: Correlation between average appreciation and offensiveness for separate social background variables.

| Men | –.29 | N = 200 |

| Women | –.40 | N = 117 |

| Education up to secondary level | –.46 | N = 187 |

| Education college level and up | –.39 | N = 147 |

| Up to 30 years | . 00 | N = 81 |

| Age 31-60 | –.48 | N = 208 |

| Age 61 and up | –.77 | N = 48 |

| All respondents | –.44 | N = 340 |

Table 6 shows connections between funniness and offensiveness for separate groups. Even when groups do not differ in their judgments of what is coarse, they may have different views on how transgressiveness contributes to a joke’s funniness. Correlations between ratings for offensiveness and funniness were quite similar for men and women, and for people of different educational backgrounds. Although these background factors affect appreciation, and, as we will see, they sometimes affect the judgment of offensiveness, relations between these judgments do not differ. In other words: the consequences of offensiveness do not differ for men or women, and people with more or less advanced degrees.

Age, however, greatly impacts on the consequences of offensiveness. Respondents under thirty did not connect funniness and offensiveness; respondents between thirty and sixty connected them as strongly as did the population as a whole. Among those over sixty, I found a strong inverse correlation. Older people are not only more sensitive to the transgression of certain pain thresholds: for them, offensiveness always makes a joke less funny. For younger people, the offensiveness of a joke is a completely separate issue from its funniness.

These figures reflect average joke scores. Much individual variation is lost here. There were no jokes in the questionnaire that were not liked by someone, sometimes. Of all the jokes in the questionnaire, there was not one that was not deemed the best possible (score of 5) at least once and the worst possible (score of 1) at least once. For offensiveness, the spread (standard deviation) in evaluations was even wider.

Even amongst the most tabooed jokes, the harsher ethnic and racial jokes received the highest possible score from some respondents. Often, these high scores were given by respondents who had voted for extreme right wing parties. This is evidence not only for differences in pain thresholds, it also shows the effect of agreeing with a joke, in other words, of identification. Presumably, these respondents not only saw these jokes as less hurtful but also agreed with their intent.

Here, the role of identification can be distilled from the questionnaire. In the case of the people with anti-immigrant views, the identification is positive. The opposite happens too: religious people appreciate jokes about religion significantly less than others. Regional identifications may intensify sensitivies as well: people from Rotterdam appreciated a joke about their local football team significantly less than other respondents:

Willem van Hanegem approaches van Gaal and says: “I’ve heard that football’s connected to intelligence. Have you ever heard that?” “Yes”, says coach van Gaal, “football has a lot to do with intelligence. Watch while I demonstrate.” So he calls Kluivert over and asks: “He’s your father’s son but not your brother. Who is it?” “Dead easy,” says Kluivert, “it’s me.” “See what I mean about intelligence?” says van Gaal to van Hanegem. So van Hanegem tries it out for himself. He calls Ed de Goey over and says: “It’s your father’s son but not your brother. Who is it?” de Goey, who has to have a good think about that, walks around the field a bit. On his way, he asks Taument the same question and he says: “Yeah, of course! That’s me.” So Ed de Goey returns to van Hanegem and says: “I know who it is. It’s Taument!” No, it’s not”, says van Hanegem, “it’s Patrick Kluivert.”32

Whether someone is offended by a joke may be mitigated or intensified by identification: the extent to which people take a joke personally, or agree with the purport. The role of identification in the appreciation of jokes, and in the mitigation or intensification of offensiveness is discussed in the next chapter. In the interviews, the question of boundaries had a much more central position in the discourse on humor than identification. People always find it easier to indicate why something is not funny. Distaste is more easily put into words than preference.

Tempting the laugh

What does this negative connection between coarseness and funniness mean? Do people like jokes less because they go too far? Or is the opposite true: do people think a joke is more offensive because they don’t like it? In everyday life, people seem to assume the former: coarseness negatively influences appreciation.

In practice, people can like a joke and think it goes too far coincidently. A serious boundary transgression, incorporated into a good joke, can tempt people to laugh at something they disagree with. An audience can be carried away by a good storyteller or a good joke with a clever, original or unexpected punch line, while disagreeing with its content. As Huibert Busser, the personnel worker cited at the beginning of this Chapter, said about the Dutroux joke cycle:

Those Marc Dutroux jokes. I never tell them. I don’t like them and I’ve got children too. They don’t make me laugh either, I don’t think they’re a nice form of humor. Although, if I have to be completely honest, someone told me one last week and I burst out laughing in spite of the fact that I... Well, when I’m listening, yeah, I do think it’s funny but it’s not good at all what happened. Someone said: “There’s a new Citroen on the market with three hidden children’s seats. Called the Citroen Dutroux.” Yeah, I had to laugh.

And 51-year old electrician Joost Wiersema:

Well, now and then you get these racist... and sometimes you find yourself laughing. I catch myself at that sometimes. About Turks, it’s a lousy sort of humor. No, I don’t like that kind of thing. But, in spite of all that, sometimes there’s a real find in one of those lousy jokes and then you end up laughing whether you like it or not.

This means that people are laughing against their better judgment: amusement trumps moral condemnation. Someone I spoke to for my study of ethnic humor said: “I don’t like it, but my sense of humor does” (Kuipers 1995). While it may not be entirely legitimate to hide behind the bloody-mindedness of your sense of humor, this statement illustrates how amusement can be a reflex reaction. Harder jokes may produce such mixed feelings: shocked, but amused nevertheless.

The moral judgment about the joke is often no match for the qualitative judgment about the “real find”, as Wiersema calls it. How a joke is put together is more important than how hurtful it is or even: what it is about. For jokes “on the edge”, the joke’s quality balloons in importance. As it becomes more hurtful, more must be done to tempt a listener to keep on seeing it as a joke. The joke technique has to be better, the storytelling more convincing.

Joketellers have to find a balance between funny and offensive. A joke that goes too far is no longer funny, but a joke that is not funny, goes too far more quickly. To an audience, a funny joke about a sensitive topic can tempt them to laugh, but an unfunny joke about a sensitive subject is nothing but an insult, a coarse remark or a dirty word.

How does this temptation to laughter work? There is no universal formula for joke quality. One can, however, illustrate the difference between a very good and a decidedly less good joke. These two jokes share the same topic:

A racist in Amsterdam gets into his car every evening and goes and runs down Turks. One evening he gets into his car and drives away. There goes a Turk. He puts his foot to the floor, looks in his rearview mirror, and bingo, one down. He does this another couple of times. Then he sees a minister trying to hitch a ride so he picks him up. The driver sees another Turk but thinks: “I won’t run him down, I’ll just drive right up next to him.” He’s already passed the guy when he looks in his rearview mirror by habit and sees the Turk lying there dead anyway. The minister says: “Good thing I opened my door, or you would have missed that one.”

What’s the difference between a rabbit and a Turk that have been hit by a car? There are no skid marks for the Turk.

While the subject of these jokes is approximately the same - running down Turks for racist ends - one is funnier than the other. The first joke was on the questionnaire and was found to be almost as offensive as the joke about the migrant hunting license, but significantly funnier. Its punch line is more unexpected. A second impropriety has been added in addition to ethnic aggression, granting it some legitimacy: the minister condones the action. The second joke is less sophisticated, with a shorter build-up and only one script. It is thus less successful in convincing the audience to see it as funny instead of offensive.

Two jokes cited earlier demonstrate a similar difference in quality. The joke about Johnny and his teacher (“That’s good, but I meant chewing gum”) has almost the same punch line as the joke about the last names of Madonna, the Pope, Wolfowitch and Bush. The listener is supposed to think of a penis, but the punch line comes up with something more innocent (chewing gum and last names). The joke about Johnny, however, is more extensively constructed and events are repeated three times. The insinuation is brought to life by letting the teacher blush - which adds a touch of Schadenfreude. With this insinuation, an extra sensitivity is evoked: the balance of power is reversed. The joke about last names also evokes taboos other than sexual ones: the Pope, Wolfowitch, Bush and possibly Maddona are persons of stature. The unseemly references in this joke, and certainly those in the punch line, are tamer than in the joke about Johnny. The most important difference, however, lies in joke structure and technique. If the punch line about last names had been incorporated into a real story, it would have been much funnier.

World-class jokes: Joke tellers on joke technique

Joke tellers generally answered the question of what they thought was a good joke first by explaining what was bad: the joke should not be too offensive, coarse, racy or hurful. First they indicated the margins within which the joke could be good. When I asked joke tellers to explain what a good joke was their answers usually had little to do with the joke’s content. Their answers were about joke form. Because joke tellers tend to classify jokes according to the content, this question often created some confusion. As Hans Wagenaar, the factory worker cited extensively in Chapter 3, said when I asked what he thought were funny jokes:

Oh alright. Jokes about people in bars and and... [silence] I don’t really have an enormous preference for what I like. I like a joke that’s just told normally, one that’s reasonably up-to-date, well, that’s not always possible, is it? Actually, if the joke is just really well put together, then I usually have to laugh. So you can’t really say I like one type best. I’m not going to tell you: it’s hard to recover from Belgian jokes because I’m rolling on the floor, or jokes about Turks or people from Surinam or any of that. Being discriminating or what have you, none of it matters to me. If it turns out funny and it’s just a good story, I laugh.

Every joke teller has a joke he sees as his best joke. When I asked what made this joke so good, the answer never referred to theme or content, but to build-up, the punch line and form. As Wagenaar said, it should be “well put together”.

Huibert Busser’s answer at the beginning of this chapter was typical. For a joke to be good, the joke had to hold the attention of the listener from beginning to end; there had to be an unexpected twist. Other joke tellers said, for example:

What do you think are the best jokes?

Long jokes. With a really dry punch line. Something that sends you barking up the wrong tree. I think that’s the best work. For example [he tells a long joke indeed about a confusion of tongues between a farmer from Groningen and a Frenchman in a Parisian hotel]. You have to make a long story of it, that way it’s most effective. That’s the sort of joke I’m really crazy about.

(Joost Wiersema, 51, electrician)

There are sexual jokes that are so good, so cleverly worked out in their build-up, their story, their atmosphere, but you can’t tell them because the point is obscene, but to my mind they’re really so perfect. [He tells a medium off-color but rather distasteful joke.] So that’s not possible, is it? While really, as far as jokes go, it’s a world-class joke. Because it turns out so surprisingly. That’s the way a joke should be. It has to be surprising. You shouldn’t get the feeling that you know where this is going.

(Eelco van Doorn, 48, entertainer)

To me the real power of a joke is: you tell some stupid story and when no one is expecting it anymore: boom! the coin drops! [He tells a joke about a man who won a goose in a lottery and then kept it in the belt to his trousers.] Now that’s a real joke, all the way through the joke not one thing happens, just some really silly story, and then who would be expecting such an ending? Look, and that’s what I think telling a joke is. You get everybody’s attention, everybody knows what’s going on, everybody’s had something like that happen to them sometime or other, you know what I mean. And everybody’s paying attention and wondering when it’s going to happen, but not one of them knows when it’s going to happen, and then along it comes and everybody collapses.

(Albert Reiziger, 40, longshoreman)

Is there are a certain kind of joke you like really well, or do you not have favorites?

No, I couldn’t say that. The joke is what matters. Yeah, the joke is what matters. What matters is the joke. The punch line is what matters. That’s what it’s all about. A good joke with a story and then a punch line you didn’t expect. And then it doesn’t matter if it’s about Turks or...

(Frederik Doeks, 64, retired sales representative)

Many joke tellers told me their “best joke” to support their argument. I did not include these jokes in the quotes but they are without exception long, spun-out jokes with lots of carefully constructed suspense. The descriptions of these world-class jokes point in the same direction as the questionnaire results: the longest jokes are the best. Joke tellers were quite scornful about riddles and brainteasers: if they told one at all, they did so preferably in between the longer jokes. A joke that tells a story creates more opportunity for a real performance: within a long story more space is found for the art of storytelling.

The way joke lovers talk about the characteristics of the good joke fits well into the division into humorous styles proposed by literary scholar Walter Nash (1985). He arrives at a elegant and effective division into two basic humorous styles: compression and expansion. These style resources can be found in all forms of humor: the short, pointed humor of wit versus the continuously expanding hilarity of humorous stories, events and performances.

The joke is a genre based on expansion. It is suited to long digressions, and an expansive storytelling style is the strategy chosen by almost all joke tellers. Even people who did not like jokes judged them according to this criterion: the more elaborate, the better. Compression, on the other hand, is humor appreciated instead by many joke haters: ironic, witty remarks, jokes with hardly any framing; humor that is not built-up but just whisks past and then disappears into thin air.

Nash’s division does not, however, coincide with the division into highbrow and lowbrow humor. The distinction between compression and expansion runs through all humor styles. Herman Finkers, popular among joke tellers, is a master of condensed, pointed jokes. Comic monologues by Freek de Jonge or the absurd humor of Monty Python and Jiskefet are highbrow, but are based on an expanding sense of absurdity building up in the course of a skit.

All joke tellers described a good joke in similar ways: long build-up, good punch line. However, they did not agree about the dosage of this expansion. Some people liked really long, spun-out jokes, others lost patience more quickly. Spinning something out is a technique with a clear risk, something all joke tellers mentioned in warning, and something many joke haters objected to: predictability. This does not necessarily mean that someone really can figure out the punch line ahead of time. “Predictability” rather means that the listener loses interest before the punch line. Expansion carries the risk of boredom and with it the disappearance of the surprise effect crucial for humor.

There were a few dissidents among the joke lovers: people who preferred short, quick or sharp jokes; or who used both forms alongside each other. Some joke tellers had a less exuberant storytelling style, and they often preferred somewhat shorter jokes. One joke teller from Groningen, in the north, based his preference for shorter, “dry” jokes on his regional background: “So I really don’t like very long jokes. You can see the punch line on the horizon miles ahead of time. What I like most is a short joke, but loaded” (Alfred Kruger, 61, sound technician). He compared himself to comedian Herman Finkers, whose regional upbringing (from an area near Groningen) he also connected with his pithiness.

Short, quick jokes are often associated with “dryness”: humor presented as not too emphatically funny. People in the rural east and north of the country tend to champion this. In the more urbanized west, but particularly in the Catholic south, people instead describe their own humor (and their accent) as “juicy”. It can’t be entirely a coincidence that these metaphors refer to opposites.

Apart from dryness, an important reason to prefer condensed humor is to enhance a shock effect. Those who like harder jokes often told short, sharp jokes. Their ideal joke was different. As 26-year old Gerrit Helman said about racist jokes: “I think the longer they are, the less punchy they are. The shorter, the fiercer. So then they’re harder too, of course.” They often reacted to the longer jokes with some irritation: “Moppentoppers with a whole bunch of gestures and a kind of precious theatre acting: really not my thing”, said Richard Westbroek (25, technician). Racist jokes, explicitly dirty jokes and sick jokes are often not much longer than a couple of lines.

There is one more domain in joke culture where short, compressed jokes flourish: children’s joke culture. The youngest interviewee, a 15-year-old schoolgirl, told mainly short jokes and riddles. The telling of jokes is a skill that children learn relatively late, and telling long jokes requires considerable skill (McGhee 1979; 1983). Perhaps this is also because formal education is such a central part in children’s experience. Riddles strongly resemble a test. Stupidity, the main theme of the Belgian jokes extremely popular with children, may appeal more as a theme to groups whose cognitive skills are constantly being tested.

Children’s joke culture is quite separate from the joke culture of adults. Their repertoire differs in both theme and form from the jokes of adult joke tellers. Jokes are not only shorter but also much more absurd. Where themes overlap, like in jokes about sex, children’s approach to the subject differs strongly from that of the adult joke tellers (cf. Meder 2001).

In the previous chapter, which dealt with content, I arrived at a much broader classification. When it comes to form, the classification is much simpler: expansion versus compression. This suits the genre well: jokes are rather varied in terms of content but much less in form. An oral genre like the joke benefits from a clear and standardized form, which makes possible almost endless variations in subjet matter.

The importance of joke-work

The questionnaire results confirmed the importance of expansion as the basis for jokes in a most unexpected way. A very simple factor has a huge effect on appreciation: the length of the joke. For the majority of respondents, the longer the joke, the funnier.

This is one of the most unexpected discoveries of this research: a correlation of .55 (p<.01) was found between the average appreciation of the joke in the questionnaire and the number of words in the joke. The length of a joke is thus an indication of its potential to amuse: in other words, its quality. The statistical connection between appreciation and word count was stronger than between funniness and ofensiveness: the number of words in the joke thus better predicts its appreciation than the extent to which it offends! Moreover, this correlation remained intact when it was split up into gender, age and educational level. Few differences thus exist between social categories in judging a joke’s form. The same result was obtained for all social groups: the longer the joke, the funnier it was.

People with different educational levels and humor styles, and men and women, do rate jokes differently, on average. However, the relative judgments by these groups are quite similar. In other words: the different groups do not appreciate jokes equally, but employ similar criteria to determine what a good or a bad joke is. As we saw, this is reversed for age difference: no difference was found in average appreciation of the jokes, but the scores ascribed to the jokes themselves show a wide spread. People of different ages do not like jokes less or more: rather, they like different jokes. Hurtfulness, it seems, defines the margins within which the joke can be funny. Whether or not it is funny depends on the joke itself. The length of the joke seems to be one of the main factors determining this judgment of a joke’s quality.

What does this connection between the length of a joke and its appreciation mean? I think it supports the joke tellers’ insistence on the importance of a good build-up. Longer jokes allow more time for approaching the punch line in well-chosen steps, for adding more context, and for working towards an expectation which can be reversed more effectively in the denouement. The most popular jokes, such as the joke with the stuttering Bible salesman, or Johnny and his teacher, were long because they follow the characteristic threefold pattern. This provides enough context to set the stage for the punch line. What happens the third time must be incongruous but, in order to be humorous, not completely meaningless. The more context the listener has, the easier it is for this incongruity to be soluble, understandable, or “appropriate” (Oring 1992, 2003).

Moreover, a long build up gives the audience time to get into a mood, allowing it to be carried off into the “humorous mode” as Mulkay (1988) calls it: the playful, non-serious mood in which one does not take things literally. This humorous mode makes things which usually cannot be done or said acceptable: “In the humorous domain the rules of logic, the expectations of common sense, the laws of science and the demands of propriety are all potentially in abeyance. Consequently, when recipients are faced with a joke, they do not apply the information-processing procedures appropriate to serious discourse.” (Mulkay 1988: 37). Humor implies a mindset or “frame” with it own own rules. The criteria for successful humorous communication are not “true” or “untrue”. The only thing that counts is “funny” or “not funny” (Raskin 1998). The power of this frame or mood is evident from comedy performances and other public forms of humor: the more the audience laughs, the funnier everything seems to be. This probably applies to the length of jokes too: the longer they are, the more time there is to get “into” the joke.

Form - quality, joke technique, delivery - is but one of the ways to bring about the transition to the humorous mode. The setting and the storyteller also both play an important role in creating a humorous atmosphere. Everyone has experienced a situation in which everything seemed funny, no matter how bad the joke was; or a joke teller that was so naturally funny that everything he said was hilarious. The opposite happens too: sometimes the situation can be so serious or the mood so dejected that even the best joke doesn’t come across.

To achieve any humorous effect at all, it is essential that the correct mood be created. Whether or not the joke can tempt someone to laugh is, in the first instance, a question of humorous technique or “joke-work” and not of subject or import. These formal aspects of humor lie not only in difficult-to-quantify issues like joke quality or performance but also in simple questions of form, like joke length.

Rather to my surprise, the discovery of how important the length of a joke is confirms the argument - but not necessarily the entire theory - of Sigmund Freud. He began his book Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1976 [1905]) with an extensive, usually ignored, exposition of “joke-work”: the build-up of jokes in language and text. These humorous techniques were important to Freud because they made possible the expression of unconscious longings and urges: by camouflaging them as a joke, sexual or aggressive thoughts could be smuggled past the censor or superego. Freud took the form of the joke as the starting point for his analysis. He compared it to the dream in its ability to “unlock” the unconscious.

Although I do not necessarily agree with Freud that there is a “censor” that has to be misled, there are always barriers to overcome, both internal and external, before people are able to lose themselves in the humorous mode. These restrictions can range from social restrictions and taboos to internal inhibitions, but also the more mundane conventions governing everyday life, such as the fact that most communications are serious and any attempt at humor entails the crossing over into another mood and frame. That is the quality of a good joke: it is capable of tempting people into crossing such boundaries, and thus into laughter.

“Humor is humor”: The incompatibility of humor and morals

To tempt someone into laughter: that is the power of a good joke. If people are amused, they consider only the quality of the joke. The humorous mode blocks other emotions: this non-serious mood combines badly with sympathy or feelings of tenderness, anger, embarrassment or indignation (cf. Billig 2005; Martin 2007). This is why inappropriate humor often evokes strong feelings of outrage: a good joke temporarily switches off moral considerations. In the humorous mode, ethics do not count. In this respect, humor is not unlike play, art, entertainment, or ritual: it is framed as “non-serious” and separated from the “real world”. Often, such “non-serious” forms of communication imply some form of transgression, for instance into (mock) violence, exuberant emotion, irregular or licentious behavior.

This means that if a joke does tempt someone into laughing, all rules, including the rules of humor - that to offend is bad, that certain words may not be used, that ladies and the elderly must be respected - may become temporarily inoperative. Sometimes one loses sight of these rules altogether, but often an ambiguous mood comes into existence in which hearing a joke makes you is angry, embarrassed or touched and amused all at once. Especially highbrow humorists try to bring about this ambiguity. Lovers of popular humor are less drawn to this ambivalent form of humor.

This power of humor to suspend moral considerations is the backdrop of many discussions, prohibitions, scandals and much censure surrounding humor. Hurtful, revolting or offensive jokes can use the non-serious nature of humor to go further than hurtful, revolting or offensive statements can; this often evokes strong reactions, particularly because jokes of this nature continually threaten to escape moral judgments. Racist jokes - the most contentious genre - exist not just because they express thoughts people do not dare express in a serious mode. The jokes are upsetting because certain ideas are capable of adopting humor as a vehicle, to such an extent that they become attractive into the bargain. Thus, they can occasionally tempt people, who would never express these ideas seriously, into laughter. Humor is most threatening - and therefore potentially attractive - if it breaks through the moral or emotional boundaries that people cherish.

The amoral character of humor forms the background of my informants’ protracted discussions of what went too far and what was permitted. They talked about it so much because there is no unequivocal solution to the dilemma. The joke tellers themselves often contradicted their own forceful statements on impermissible jokes. The discourse about humor and boundaries reveals a certain degree of internal contradiction. Many joke tellers began by resolutely dismissing jokes about foreigners, illnesses, incest or religion. One of the interviewees said he did not consider jokes about incest permissible under any circumstances. However, at the Moppentoppers selection I heard him tell an incest joke, admittedly sotto voce. The woman who made such bellicose statements earlier in this chapter about Dutroux had told a whole series of these jokes at an earlier meeting. The man who assured me that he did not wish to hear a single joke about illnesses, had shortly before told me a joke he found highly amusing about a hydrocephalic boy. He followed it up, apologetically, with: “Well, for me humor is humor”.

At first I thought that these contradictions were connected with my presence: that the interviewees were assuming I would have a problem with offensive jokes. I also thought it perhaps was due to the situation-dependent nature of hurting and shocking: if no one is present who can be hurt, perhaps it doesn’t count as hurtful. Both considerations are partially true, but neither clarifies the enormous contradictions I encountered in many interviews. Joke tellers like Gerrit Helman were aware of this too: “Things I think you shouldn’t tell? Jokes about illnesses or things like that. Like, your parents have died of cancer, and you start thinking about it, you know? But I tell them anyway!” As is apparent from his account, he was aware of his inconsistency; this was true of many (perhaps all) of the joke tellers I spoke to.

Two conflicting ideas lie at the heart of people’s attempts to determine the dosage of funniness and coarseness: the concern that jokes should not go “too far” is set against the - quite pertinent - observation that “humor is humor”. I heard the statement quite often and it forms an integral part of the discourse on joke culture:

Humor is humor. If I’m watching a film, I’m aware that none of it really happened and that applies to jokes too. A joke is a joke.

(Egbert van Kaam, 34, fairground worker)

Yeah, humor is humor and as far as I’m concerned anything’s possible.

(Fred Crooswijk, 76, retired entertainer)

And at the same time they found some jokes completely represensible. Where humor is concerned, internal contradictions are the order of the day. Humor escapes from moral judgment, but also provokes it at the same time. This is what makes discussions about jokes that go too far - that I have been involved in over the years and to which I have been witness even more often - so difficult to negotiate (Kuipers 2011; Lewis 1997; Lewis 2008).

The best way to deal with this ambiguity is self-censorship: risky jokes are only told in closed company. “You have to keep it separate. I’d never tell that in public, if you could hurt people head on like that. But among friends, a few guys in the living-room, sure, no problem. They have to be friends, you know, safe” (Egbert van Kaam). This solution works as long as some consensus exists about what goes “too far”. In the Netherlands, this appears to be easier to realize than in a large and heterogeneous society like the United States. During my fieldwork in the late 1990s, I found considerable agreement about the impermissibility of jokes connected to ethnic difference, illnesses, disabilities and the Second World War. Jokes like this were seldom submitted to Moppentoppers, to joke pages or even to websites (Kuipers 2006b). However, as I lay out in the introduction to the current edition (2014), this consensus appears to have crumbled since the late 1990s, and self-censorhip has ceased to be self-evident.

Conclusion: temptation, transgression, and joke quality

Every genre determines its own norms: so too with the joke. Within the conventions of the joke, people show a surprising agreement about which jokes are better or worse. Joke haters can distinguish a good joke from a bad one, and they do this in the same way as joke lovers. Thus, there exist quality criteria for the genre that go beyond humor styles.

These criteria have to do primarily with the form of the joke. The length of the joke is a (very simple) measure of quality that remarkably influenced the appreciation of jokes. Differences in appreciation are mainly related with joke content. Within the margins of their sensitivities, people all employed roughly the same criteria for a good joke. In order to be found funny, a joke must be well built-up and extensively spun-out, and should preferably refer to different taboo subjects at once. The core of the joke has to be unexpected and funny or, in harder jokes: the punch line must include a good shock effect. If the punch line is no good, the joke will usually not be amusing; but, if someone doesn’t think the joke’s subject is good joke material, it can still be a funny joke.

Research in the social sciences into taste difference leads quite quickly to relativism. A taste is viewed as a cultural phenomenon, a completely self-contained system of norms and criteria adhered to by a certain group of people. There is no place for a concept like quality in an analysis of this sort, or only as a result of a specific cultural system. The complete lack of a concept like quality unavoidably leads to a distant relativism that often makes cultural sociology rather sterile. As I have noticed myself, some indication of one’s own thoughts always filters through a description; research into taste and style, liking and disliking, cannot really be done independently of some concept of quality. To research humor, the question of what constitutes “good” humor has to be asked - even if the answer threatens to remain unsatisfactory.

The discovery that people with little appreciation for the genre use the same criteria for quality as people who like it, underlines that quality does not have to escape completely from scientific exploration. Even outside the domain of taste differences and socially determined tastes, people can point to a gauge for quality. Indeed, for a relatively simple genre like the joke, it is possible to come to grips with this: quality in a joke lies in it capacity to successfully tempt people to laugh.

Therefore, some jokes are better, more attractive and funnier than others. Yet, in spite of this consensus about the quality of jokes, not everyone thinks the same jokes are funny. There are, for instance, huge style differences between joke tellers, both in delivery and repertoire, and considerable variations in where the boundaries are placed within which one may laugh. In the following chapters, I look into differences in how separate persons appreciate separate jokes. Who laughs at what? Which jokes are valued by which types of people? We will no longer dealing be with form and hardly at all with style: the appreciation of specific jokes is mostly connected to their content, and to identification.