- Cannery Row today.

”As everyone knows meditation and water are wedded for ever.”

New Monterey is liminal space on the peninsula—not Spanish Monterey, not Methodist Pacific Grove, but the shoreline and sloping wooded hills between these places, where fishermen and immigrants established roots. It’s a place between two communities with clearly demarcated boundaries and histories. In New Monterey, industries took hold, flourished, and vanished, only to be replaced by other ventures, much like waves of ecological succession in the rich waters just offshore. The Chinese dried squid in New Monterey. Sicilian fishermen came here. Beginning early in the twentieth century, canneries and reduction plants were built in New Monterey, and the area supported the region’s lucrative sardine industry until the industry collapsed in the late 1940s. In 1945, John Steinbeck put this in-between land on the map, so that the fame of Cannery Row would eclipse that of all other peninsula locales.

Cannery Row in Monterey in California is a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream. Cannery Row is the gathered and scattered, tin and iron and rust and splintered wood, chipped pavement and weedy lots and junk heaps, sardine canneries of corrugated iron, honky tonks, restaurants and whore houses, and little crowded groceries, and laboratories and flophouses.

Cannery Row made a hero of Doc, the novel’s central character, who was, in life, Edward Flanders Ricketts, a marine biologist who operated a small marine biological lab in New Monterey. He was John Steinbeck’s closest friend for eighteen years, and their friendship was essential to Steinbeck’s thinking and his art. Beginning in 1930 when they met—either in a dentist’s office (Steinbeck’s version) or at a Carmel party (more likely)—Ricketts was a touchstone for Steinbeck. “Everyone found himself in Ed,” Steinbeck wrote, and that everyone included Steinbeck himself. It was arguably the most vital connection of Steinbeck’s life—fulfilling some deep psychic need more completely than any other relationship, including those with his three wives. In nearly every one of his novels, a male character offers to another male solace, wisdom, insight, and the “toto picture,” to borrow a favorite phrase of Ed’s. These men, always solitary but generally embedded in a social maelstrom, are intimate friends and mentors to Steinbeck’s protagonists. Their significance is relational, for the bonds forged are marked by honesty, commitment, companionship, even love. Male friendship is more deeply satisfying, more complex, and more significant than any other union in his fiction.

Ed Ricketts inside his lab, 1945.

For eighteen years, Ricketts and Steinbeck were intellectual sparring partners, soul mates, and collaborators. They discussed any and all subjects—the mathematics of music, observations of animal behavior, interpretations of modern art, the philosophy of Carl Jung. If Pacific Grove was Steinbeck’s home and writerly retreat, the lab in New Monterey was where ideas were forged. In the little laboratory by the sea, John Steinbeck’s mind moved outward. There one of the peninsula’s most beloved residents, Edward Ricketts, and one of its most famous, John Steinbeck, forged perhaps the most unusual and significant collaborative relationship of the twentieth century. To set down Ricketts’s influence on Steinbeck is to trace interweaving threads that bind together science, metaphysics, and holistic thought.

Ricketts made his life’s work the sea. Born in 1897 in Chicago, he came west in 1923 with fellow marine biologist and business partner Albert E. Galigher. At the University of Chicago, both men had been students of Warder Clyde Allee, whose theory of “mutual interdependence or automatic cooperation among organisms” helped Ed formulate his own beliefs about cooperation, both in animals and in humans. Their life in the West began as a joint effort: Ed’s wife, Anna, recalled that the men “decided that it would be best if the two families lived together on a share basis, sharing car, house and food. We could all benefit that way and put most of the monies into the firm”—a biological supplies lab in Pacific Grove. For a year, that mutual effort (all four collecting marine specimens) helped establish one of the first biological supply houses on the West Coast; the 1925 catalogue offered for sale marine creatures from microscopic organisms to rays, octopuses, hagfish, starfish, and jellyfish, as well as rats, frogs, and cats. But establishing a business was tough going, and in 1925 Galigher departed for Berkeley. For most of Ricketts’s twenty-five-year career on the peninsula, his business bumped along, rarely prosperous though never insolvent, thanks in part to Steinbeck’s significant investments and in part to Ed’s own quirky business practices—leaving bills unopened, according to friends. But he cast a wide net of economic goodwill by paying local kids to collect eels (two cents), frogs (five cents), cats (twenty-five cents), and rattlesnakes (price varied). Ricketts was most certainly scientist first, businessman last.

If business practices were never Ed’s forte, innovative thought about ecology was. Ecology is the science of connections between organisms and their environment, and his keen mind saw connectivity as a bedrock of scientific inquiry—a holistic viewpoint hardly appreciated by marine scientists in the 1930s. This philosophical foundation led Ricketts to be a great generalist—he never specialized in any particular group of animals or specific subject like anatomy or physiology or embryology. Indeed, it’s impossible to peruse Ricketts’s papers (held at Stanford University, his letters collected in Renaissance Man of Cannery Row) and not be dazzled by the range of his scientific interests, the extensive scientific bibliographies he prepared, and the volume of his epistolary exchanges with other scientists. Ricketts read widely in scientific literature and observed the natural world with full “participation,” a favorite word of both Ricketts and Steinbeck—meaning, for both, full engagement of the mind and senses.

Edward Flanders Ricketts “had more fun than anyone I’ve ever known,” wrote Steinbeck in 1951.

Ricketts’s lab.

Ricketts’s range was broad. He studied vitamin A in shark liver oil, sending small vials of oil to friends afflicted with arthritis or asthma or having ovaries removed. He wrote an essay on wave shock, noting how marine animals were affected in different intertidal zones. He planned a handbook on the intertidal life of San Francisco Bay (with Steinbeck), compiled the phyletic catalogue for Sea of Cortez (1941), and was planning a similar work for the “Outer Shores” off British Columbia the year he died (1948).

This breadth of marine interests was the scientific side of the holistic view of life that Ricketts cherished, one that guided his attempts to synthesize complex interconnected biological phenomena. He spent hours compiling data on fluctuating plankton levels measured in sea water—his own measurements as well as those from marine stations in La Jolla and the Aleutian Islands. He concluded in a 1947 letter to Joseph Campbell that there was “a primitive biological rhythm operative over the whole of the north Pacific.” (He shared that insight with scientists at nearby Hopkins Marine Station, who, ten years earlier, had published findings on “a predictable rhythm in the changes in temperature of water in the bay.”) Ricketts combined these observations with data on declining sardine populations of the 1940s in a series of newspaper articles that viewed the problem holistically as one involving changing ocean temperatures, plankton supplies, and overfishing. His prescient view continues to be one that marine scientists of today struggle to develop.

Much of Ricketts’s scientific passion, some assert, is muted in Steinbeck’s accounts of the affable but detached Doc in Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, and “The Snake,” a story set in the lab. The fictional Doc embalms cats, prepares invertebrate specimens, mounts developing starfish eggs on microscope slides at precise times, collects at low tide, and struggles with writing a scientific paper. Ricketts did all these things. Although Ricketts didn’t write with Steinbeck’s fluidity, he tirelessly revised a series of essays on science and human psychology, working hard to articulate complex ideas—as does Doc in Sweet Thursday.

Ricketts produced his own seminal work, Between Pacific Tides, the same year that Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath, 1939. Published by Stanford University Press and now in its fifth edition, Between Pacific Tides is historically important and remains a valuable text. It was the first work to classify the sea life of the Pacific coast by specific zones of the intertidal environment, stressing interconnections among the different species that inhabited the “protected outer coast,” the “open coast,” and the “bay and estuary.” To Ricketts, the important unifying theme was the community of organisms—how the different species interacted with each other, and how the specific habitat type determined the structure of its own community. This was a radical departure from the traditional approach of classifying organisms by taxonomic groupings, or phyla. Ricketts’s handbook is practical, and easily readable by the nonscientist; the current edition is available in the Monterey Bay Aquarium bookstore.

Frontispiece from Between Pacific Tides, second edition (1948).

“I am a water fiend. I think that is why I need these fish bowls. Water is everything to me.”

During the years that Steinbeck lived in his family’s 11th Street house in Pacific Grove, (1930-36), he would usually work until late afternoon and then often walk two blocks down the hill toward the bay, turn right along Ocean View Avenue, and end up at Ed Ricketts’s marine supply lab, snug against the sea on what was then simply “cannery row” in New Monterey. Walking this path allows one to feel the allure of water, to sense that humans are, as Herman Melville reminds us at the beginning of Moby Dick, essentially “water-gazers.” For water-gazers, the sea suggests all that is elusive in human experience, what Melville calls “mystical vibrations.” Steinbeck felt these vibrations. He had “a spiritual streak,” said Elaine, his third wife. He was a water-gazer.

John Steinbeck, circa 1938.

Certainly he loved living near the ocean. “I don’t like Yosemite at all,” he wrote his godmother in 1935. “Came out of there with a rush. I don’t know what it was but I was miserable there. Much happier sailing on the bay.” Friends say that young John, something of a loner, took long walks on the beach when his family came to Pacific Grove each summer. On a trip to New York City in 1937, reported his agent Elizabeth Otis, John and Carol “went up and down the escalator at a major department store, and every time he got to the sporting goods section he’d go over and touch a boat.” When he moved permanently to New York in 1949, it took him only a few years to buy a house near the sea, in Sag Harbor. Even before he and Elaine moved in, he built himself a small boat, later bought bigger boats, and regularly sailed and fished in the estuary around his point of land. The sport of fishing, he wrote to Harry Guggenheim in 1966, “I consider the last of the truly civilized pursuits. Surely I find it a most restful thing. And if you don’t bait the hook, even fish will not disturb you.”

Undoubtedly much of his fishing time was spent water-gazing. “Modern sanity and religion are a curious delusion,” he wrote in 1930. “Yesterday I went out in a fishing boat—out in the ocean. By looking over the side into the blue water, I could quite easily see the shell of the turtle who supports the world.” The man who could draw on an American Indian creation myth in a letter moved easily from facts to symbols all his life. “Always prone to the metaphysical,” Steinbeck wrote several months into his relationship with Ricketts, “I have headed more and more in that direction.”

Salinas mural of Indian creation myth.

Ricketts was also a water-gazer, long intrigued by metaphysics, prone to the abstract. Walt Whitman had been his favorite poet since childhood—and there was much of Whitman’s yeasty grounding and spiritual ache in him. Like Whitman, Ed was a spiritual nomad and sparked in all who came to the lab a yearning to “break through,” one of his favorite notions, to mental fields beyond the physical. Ricketts was drawn to the “true things,” in his words, an “alignment of ‘acceptance’ (= being) with ‘breaking thru’ (= becoming).” He found wholeness in music and in the poetry of William Blake, Walt Whitman, and Robinson Jeffers, all of whom embraced “not only the ‘beauty’ of ugliness, but the ‘beauty, of beauty; even more important, the ‘beauty’ of the deadly desultory … the beauty of all things as vehicles for breaking through.” To get a sense of what Ricketts was talking about, think of the mystical moments in Cannery Row: the old Chinaman’s eyes, the vision of the drowned girl in the La Jolla tide pool.

For both men, philosophic inquiry was as fundamental to the human condition as was investigative journalism or collecting marine animals. “Man is related to the whole thing, related inextricably to all reality, known as well as unknowable,” Steinbeck writes in Sea of Cortez. To live fully, that book conveys, humans must look from “the tide pool to the stars and back again.” It was not simply a theoretical position but a frame of mind that they shared throughout the 1930s—Steinbeck as both gritty realist and symbolist, Ricketts as marine biologist searching for physical and cosmic connections.

In 1928, Ricketts moved his business and then gradually his home life to Cannery Row. If in the daytime scientific work got done at  Ricketts’s lab, at 800 Cannery Row, at night the space was given over to conversation and drinking. Ricketts’s lab was New Monterey’s salon, a tiny bohemian enclave of artists, writers, and musicians who were invited for parties and dinners or simply dropped by in the evenings to see what was happening. “There were great parties at the laboratory,” Steinbeck recalled, “some of which went on for days.” The group was committed to rollicking good times, companionship, intellectual sparring, and The New Yorker, a magazine that brought New York sophistication to the shores of the Pacific in the 1930s. What happened at the lab was the kind of relaxation and friendship that Steinbeck assigns to the paisanos in Tortilla Flat or Mack and the boys in Cannery Row. In Ed’s presence people became the best of themselves, if tales told are true. And leavening it all was always the commitment to a good time: “People who are concerned with ‘the eternal verities,’” Ed wrote, “would do well to remember that fun is one of them.”

Ricketts’s lab, at 800 Cannery Row, at night the space was given over to conversation and drinking. Ricketts’s lab was New Monterey’s salon, a tiny bohemian enclave of artists, writers, and musicians who were invited for parties and dinners or simply dropped by in the evenings to see what was happening. “There were great parties at the laboratory,” Steinbeck recalled, “some of which went on for days.” The group was committed to rollicking good times, companionship, intellectual sparring, and The New Yorker, a magazine that brought New York sophistication to the shores of the Pacific in the 1930s. What happened at the lab was the kind of relaxation and friendship that Steinbeck assigns to the paisanos in Tortilla Flat or Mack and the boys in Cannery Row. In Ed’s presence people became the best of themselves, if tales told are true. And leavening it all was always the commitment to a good time: “People who are concerned with ‘the eternal verities,’” Ed wrote, “would do well to remember that fun is one of them.”

The real Ed and the fictional Doc are conflated in nearly everyone’s mind, and what emerges is a nearly legendary figure who embraced in life and embodied in fiction acceptance, relaxation, camaraderie, and conversation. “Everyone near him was influenced by him,” Steinbeck writes in “About Ed Ricketts,” “deeply and permanently. Some he taught how to think, others how to see or hear.” Rolf Bolin, head of the Hopkins Marine Station in the 1940s, said, “I went over there for the purpose of feeling better.” Ed would listen with great sensitivity and compassion. He would play liturgical music. Before the lab burned in 1936 (rebuilt on the same spot), his walls were covered in charts that traced the history of world music, art, and history.

Ed Ricketts inside the lab, 1948.

On April 24, 1948, Steinbeck wrote in his journal that he felt close to “some kind of release of the spirit. I don’t know how this is going to happen. I just know it is so. Maybe through the book maybe through sorrow or pain or something. Anyway it is near and I must be ready for it.” On May 5, he wrote, “No word from Ed. I have a feeling that something is wrong with him.” Three days later, Ed Ricketts was struck by a train as he drove across the tracks at Drake Avenue and Cannery Row (now marked by a bust of Ricketts). Having eerily anticipated the loss, Steinbeck was numb. After Ricketts’s funeral, he wrote to Ritch and Tal Lovejoy, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if Ed was us and that now there wasn’t any such thing or that he created out of his own mind something that went away with him. I’ve wondered a lot about that. How much was Ed and how much was me and which was which.”

Indeed, John Steinbeck spent the better part of the next seven years laying to rest the ghost of Ricketts and the siren call of his own past—in East of Eden (there is much of Ricketts in Lee); in the marvelous essay “About Ed Ricketts,” the preface to the Log from the Sea of Cortez, published in 1951; and in the wacky novel Sweet Thursday.

Ricketts’s spirit endured in Monterey as well. In 1956, another group took over the space that had sheltered Ed. For more than fifty years, the “lab group” held weekly stag parties at Ed’s lab. These businessmen, lawyers, and artists helped found the Monterey Jazz Festival. In 1993, the group ensured the small building’s future when they deeded it to the City of Monterey for a California pittance, $170,000. Although the building has hardly changed since 1936, the city has long struggled with the problem of how to preserve this fragile wood structure. It is now open to the public on May 14 (Ed’s birthday), during the annual Steinbeck Festival, and occasionally for other local celebrations.

One year, 1932, clarifies the vital importance of metaphysical speculation at the lab. Early that year a footloose young Joseph Campbell—later in life a famed mythologist—came to the peninsula at the suggestion of Carol Steinbeck’s sister, Idell, and spent several months in the company of Ricketts and Steinbeck. It would be a seminal year, “our year of crazy beginnings,” recalled Campbell in a 1939 letter to Ricketts. Campbell reflected on the significance of their interaction: “Since my last letter I have been pushing slowly forward, as through a swamp, toward that great synthesizing middle-point which we all glimpsed those days of the great intuitions.” Those days included nights, when the group would gather at the lab, Ricketts wrestling with the notion of breaking through physical sensations to some greater truth; Steinbeck revising To a God Unknown, his pantheistic novel; and Campbell seeking a “synthesis of Spengler and Jung…. Joyce’s new work Finnegans Wake is the closest thing I have found to a complete resolution of the problem.” The problem, for Campbell, was to trace underlying cultural patterns, the “hero with a thousand faces.”

The prevailing ideals were to defy conventional thinking, to find meaning in music and nature and spirituality and philosophy, to sift for unity, to see the “whole picture,” as Ed termed it. For Ricketts, the “problem” of unity was resolved by a group of writers and philosophers he called “Extra-humanists, the breaking-thru gang: Whitman, Nietzsche, Jeffers, Jung, Krishnamurti, Stevenson … Emerson’s oversoul. James Stephens knew it. Conrad Youth and Heart of Darkness. Steinbeck To a God Unknown, and In Dubious Battle.” All were willing to grasp a sense of the whole. “You and your life-way,” Campbell wrote Ricketts, “stand close to the source of [my] enlightenment.” “Enlightenment” is not a bad word to describe what happened to all three of them in 1932, water-gazers all.

Yet, what might have been a historical triad was disrupted by affairs of the heart. Campbell fancied Steinbeck’s feisty wife Carol. Carol fancied Campbell. John, tormented, went off into the Sierra Nevadas—departing to excite “profound pity,” thought a disgusted Campbell (whose “job” it was to “disappear,” as he and Carol had agreed, although the two continued to write one another). Campbell joined Ricketts on a collecting trip in British Columbia.

Years later, Steinbeck exacted his gentle revenge, apparently casting Campbell as the effete and pretentious Joe Elegant in Sweet Thursday, a writer who explains to brothel owner Fauna “the myth and the symbol” of his book and the “reality below reality.” She isn’t impressed: “Listen, Joe, whyn’t you write a story about something real?”

Joseph Campbell (second from right) joined Ed Ricketts (center) on a collecting trip to British Columbia in 1932.

For more than forty years, the eight- to ten-inch Monterey Bay sardine, packed six to eight to an oval can in oil or tomato sauce, gave life to Monterey’s cannery row. Each night during the season, from mid-August to mid-February, fishermen went out in boats—first lamparas, and by 1926, purse seiners—to scoop up tons of sardines and dump their catches in hoppers a hundred yards out in the bay. From the hoppers, the sardines were sucked into the canneries through underwater pipes.

In the early twentieth century demand for fish came from the East, Europe, and Asia, and fresh fish could not be shipped that far. Only drying—the Chinese method—and canning—the American method—could ensure solid profits.

The abundant sardine promised a reliable source of revenue, so after an early salmon cannery closed, sardine canneries were built on Monterey’s shores. Initially, fish offal was tossed into the bay, until the Chinese taught cannery owners that this too was a valuable resource. The first fish reduction plant was built in 1915, processing not only offal but whole fish into the much more lucrative fish oil and fish meal—fed to chickens, cows, and pigs.

Sicilian, Italian, and Portuguese men fished, and their wives and daughters packed, making about thirty-three cents an hour at cannery work until unions came in 1936 and wages rose. Conditions in the canneries were rugged—smelly and cold, workers sometimes standing in water up to their knees—but far from oppressive. Only women worked the lines. One of the biggest problems these women reported was daycare. They had to report for work whenever full boats came in after a night of fishing—large canneries owned a couple of boats and leased several more for the season. Whistle codes announced the start of the workday—at 3:00 a.m., 4:00 a.m., and 5:00 a.m. What to do with sleeping children if you were a cutter, called to work first, or a packer, allowed to arrive a little later, perhaps at 8:00 in the morning?

Women in the canneries, 1930s.

Midway along Cannery Row at  Steinbeck Plaza, a bust of John Steinbeck stands near the sidewalk. A story about that bust explains much about Steinbeck’s relationship with his first wife, Carol Henning Steinbeck.

Steinbeck Plaza, a bust of John Steinbeck stands near the sidewalk. A story about that bust explains much about Steinbeck’s relationship with his first wife, Carol Henning Steinbeck.

Unveiled in February 1973, the bust is signed “Carol Brown, Sculptress.” The identifying label is perhaps meant to distinguish between artist Carol Brown and her sister-in-law, Carol Steinbeck Brown. Married to brothers, both Carols lived in Monterey in the early 1970s. John’s former wife loved ceramics and, noted the sculptress, “that’s how we became interested in the bust. I don’t remember whose idea it was.” When work on the Steinbeck bust began, Carol Steinbeck Brown brought her sister-in-law lots of photos of John and scraps of paper with notes John had written. Together they went over memorabilia. Even though she harbored ill will toward her former husband, Carol wanted to make sure this bust was a true likeness. As the sculptress worked, every couple of weeks Carol Steinbeck Brown would visit, telling the artist to “Make his head bigger” and then swearing at the bust, venting her anger at the man who had left her for a much younger woman. Carol’s visits unsettled the artist. Indeed the first bust “collapsed because she said to make it so big.” When the project finally neared completion, Carol Steinbeck Brown considered the bust a collaborative effort and wanted recognition, her own name listed with the artist’s under the final work of art. She felt “so confident in editing or interpreting,” said the artist. “She felt she collaborated with John in the sense that she was secure in being a critic.” But neither John nor her artist sister-in-law gave Carol the recognition she craved. The artist signed only her own name to the bust. According to the sculptress, Carol Steinbeck Brown felt a “sense of being left out. She had collaborated with me on the bust and I had failed her. She had collaborated with John and he failed her.”

Stately Flora Woods appears in Steinbeck’s novels as Fauna in Sweet Thursday and Dora Flood in Cannery Row, “a great woman, a great big woman with flaming orange hair and a taste for Nile green evening dresses.” Some have said that Steinbeck sentimentalized prostitution, created stereotypical whores with hearts of gold. But Flora Woods was, in life and art, the Ethel Merman of Monterey, cutting a wide swath.

Flora’s Girls, a mural once on Cannery Row, by Eldon Dedini.

During her three decades as madame, Flora owned several brothels on the peninsula. The Quick Lunch opened in 1917 and offered patrons a hearty lunch and a roll in the sack. (Steinbeck was surely thinking of this establishment when he wrote about Rosa and Maria’s restaurant in The Pastures of Heaven.) Flora’s other houses included the Golden Stairs and one located near the baseball park, which competed “for the attention and patronage of youth.” Flora’s most infamous establishment was the Lone Star Café, Steinbeck’s Bear Flag.

“Notorious” Flora made the news regularly throughout the 1930s. When fire destroyed Ricketts’s lab in 1936, the front page of the Monterey Peninsula Herald ran both a large photo of the burning lab (Ricketts lost everything) and a small column: “Firemen save Flora Woods.”

Others were less eager to save her properties. In the mid-1930s, a local judge launched a campaign to wipe out Monterey County prostitution and Chinese gambling houses, most of which were in Salinas and Monterey. “Can Monterey Find an Honest and Sensible Way to Regulate Prostitution?” queried the Monterey Trader on January 17, 1936. “The state law bans prostitution … but the public puts up with various compromises,” particularly in Monterey, where “a lax and apathetic public,” the article complained, “has handed control of municipal affairs over to a ‘wideopen town’ majority” and thus the problem “gets out of hand.” The state of things made it “possible for Flora Woods to run her business to suit herself and to dictate to the public, or rather to the public’s officers, just where and how she will operate. And inasmuch as Madame Woods gets away with it, the increasing smaller fry follow suit.”

She seems to have gotten away with quite a bit. Bowing to public pressure in 1936, she did close her ballpark location—but one suspects that deals were struck, allowing the Lone Star to stay open. In 1942, all brothels were closed by the army. Ricketts wrote to Sparky Enea, the cook on the Sea of Cortez trip, about the “sad story of the Lone Star. Everything was moved out, including of course all the beds—and boy were there a lot of them! The front of the building was torn off, and now the place is being used to store fish meal. What a fate!”

In 1959 the city of Monterey proposed that the theater on Cannery Row be named the Steinbeck Theater. He wrote back,

Your suggestion… is of course flattering. I can only warn you that my own success in the theater has not been all rosy. You may be taking on a jinx. Having one’s name on an institution smells slightly of the epitaph and I can only assure you, but perhaps not prove, that I am not dead, certain pronouncements of critics to the contrary….

I could not stop you from using my name if I wished, since it is probably in the public domain. Would it be out of order in view of our long association, and because he was one of the greatest humans I ever knew, that Ed Ricketts’ name be substituted for mine, or if because his name is not yet as widely known as it deserves, that our names be used together?

Rodgers and Hammerstein, Buck and Bubbles, Mike and Ike, Mr. Gallagher and Mr. Shean, Cohn and Schine, Aucassin and Nicolette, corned beef and cabbage—these seem not to suffer from a duality. If your projected theater could be named the Ricketts and Steinbeck, any reservations of mine, self-conscious or sentimental, would instantly disappear, and a name that deserves remembering could be at least proposed. Thank you for the compliment. Could you, however, among the cultural clutter, sometimes put a little gut-bucket in the theater? I would feel safer if Pee Wee Russell has some small niche in the world of Bach and Rene Clair.

The theater did open, and Barnaby Conrad’s film Flight had its world premiere there.

Hauling sardines, circa 1940.

In Cannery Row, John Steinbeck devotes about a page to the canning industry. Steinbeck’s terrain is not commercial Cannery Row but after-hours Cannery Row, when the habitat “became itself again,” quiet and magical. In the half-light of sunset or dawn, during the long nights, the little enclave is like a tide pool, he writes—describing the characteristics of each human “specimen”; studying the interconnectedness of these characters and parties of human “aggregation”; tracing the fragmented histories of how individuals got the way they are; and crystallizing the universality of lyrical breaking-through moments. Steinbeck once enigmatically remarked that Cannery Row was written on four levels, levels that book critics missed. Perhaps these levels are those above, four planes parallel to those seen by Ricketts as the basis of a holistic ecology—naming and characterizing the species present, determining how they interact as a community, elucidating the complex life history of each species, and recognizing the “niche concept” by which communities of totally different species are found in widely different geographical areas.

Steinbeck’s dedication of the novel (“For Ed Ricketts who knows why or should”) says it all.

Cannery Row also maps Steinbeck’s memories. Stand in front of the lab, book in hand, and read the beginning of chapters 3 and 5 to look at Cannery Row through Ricketts’s eyes, sharing his vista—”participating,” just as Steinbeck did, just as he wants his readers to do. Today that may seem impossible in a Cannery Row that is chock-a-block with restaurants, t-shirt shops, and bars. Many feel that Steinbeck’s and Ricketts’s spirit has evaporated in the zeal for commercial development. Indeed, when Steinbeck came through the area in the 1960s, long before Cannery Row became a tourist mecca, he was glum at changes made—as most of us are when returning to places of the heart, enclaves of the spirit, spaces lost to time. But an aura lingers.

“Chicken walk” on Cannery Row, 1945.

Next to the building that was once the Lone Star brothel is Cannery Row’s “vacant lot,” once full of abandoned pipes, where Mack and the boys took the “chicken walk” up the hill.

The Wing Chong grocery.

The walk is now paved and renamed  Bruce Ariss Way, and the lot is home to three little fishermen’s houses—moved here in the mid-1990s—each furnished to reflect workers’ ethnic diversity. Ariss was a local artist, editor, friend of Steinbeck and Ricketts, and, for more than sixty years, a legend in the community. A 1989 mural panel (one of several painted by local artists to hide a Cannery Row construction site) was moved here, and another one of his paintings of 1930s Cannery Row is at the group entrance to the aquarium.

Bruce Ariss Way, and the lot is home to three little fishermen’s houses—moved here in the mid-1990s—each furnished to reflect workers’ ethnic diversity. Ariss was a local artist, editor, friend of Steinbeck and Ricketts, and, for more than sixty years, a legend in the community. A 1989 mural panel (one of several painted by local artists to hide a Cannery Row construction site) was moved here, and another one of his paintings of 1930s Cannery Row is at the group entrance to the aquarium.

Typically, Steinbeck did not revisit old work. The exception is the Cannery Row material, stories that engaged him for more than fifteen years, from 1938, when he had in mind a “magnificent story about Monterey,” to 1955, when he finally got the whole of that story out of his head.

After finishing The Grapes of Wrath, he started and then abandoned a satiric play he thought “might be fun,” “The God in the Pipes.” It tells of a man leaving Salinas—where the “people [are] so wise naturally that they need never read nor study”—to consult a Monterey prophet, the “Boss” living in a cannery pipe. He was airing some of his rancor toward Salinas.

The novel that did get written came after a 1943 stint overseas as a war correspondent; nostalgia for all he’d left found its way into Cannery Row, a knotty little book about the bums and whores, the flotsam and jetsam edging in around Doc’s marine laboratory. It is one of his best novels, a must-read for anyone visiting the peninsula and anyone wishing to understand Steinbeck’s and Ricketts’s holistic vision.

The book and its hero, Doc, were beloved by many. In 1947, Burgess Meredith wanted to work with Steinbeck on a play or film of Cannery Row, with Meredith as the charismatic Doc and with, he said, “Humphrey Bogart standing by.” In 1948, Steinbeck came to California to scout locations for a film of Cannery Row. He thought about an opera. In 1953, he started work on a libretto for a musical based on Cannery Row. He ended up with a consciously extravagant novel, Sweet Thursday (1954), intended for the musical theater. Rodgers and Hammerstein used this novel for one of their only musical missteps, the rarely performed Pipe Dream (1955).

Whimsical Sweet Thursday is Steinbeck’s swan song to California. It lacks the heft of Cannery Row, consciously so. Steinbeck’s last California novel is a wry and frothy creation: “The playful sun picked up the doings of Cannery Row, pushed them through the pinhole, turned them upside down, and projected them in full color on the wall of Fauna’s bedroom.” Anyone picking up the novel should keep that perspective in mind. It’s a cockeyed book, maybe a fictional wake as well. In it Steinbeck scatters the ashes of his best friend, writing Ricketts into a crazy little love story, and then sending him and his girl into the setting sun that shines briefly on Doc’s “laughing face, his gay and eager face.”

The two-story building at  835 Cannery Row once housed the Wing Chong, or “glorious, successful,” grocery, which opened on November 16, 1918. Five years earlier, Won Yee had immigrated to America, where he saved money and moved to Monterey to open his market, one of about a dozen Chinese residences or businesses along a two-block stretch of Cannery Row. In Cannery Row he is Lee Chong, whose “position in the community surprised him as much as he could be surprised,” writes Steinbeck—perhaps a wry comment. In the back of his store, the real Won Yee ran gambling tables and sold bootleg liquor during Prohibition and opium at other times. If police raided, patrons escaped through a tunnel that came out behind the Hovden warehouse.

835 Cannery Row once housed the Wing Chong, or “glorious, successful,” grocery, which opened on November 16, 1918. Five years earlier, Won Yee had immigrated to America, where he saved money and moved to Monterey to open his market, one of about a dozen Chinese residences or businesses along a two-block stretch of Cannery Row. In Cannery Row he is Lee Chong, whose “position in the community surprised him as much as he could be surprised,” writes Steinbeck—perhaps a wry comment. In the back of his store, the real Won Yee ran gambling tables and sold bootleg liquor during Prohibition and opium at other times. If police raided, patrons escaped through a tunnel that came out behind the Hovden warehouse.

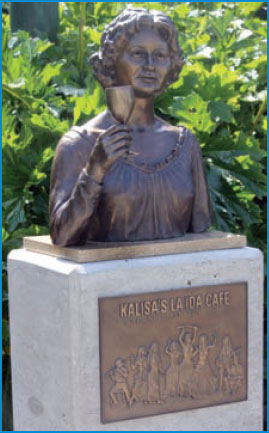

The Queen of Cannery Row, Kalisa Moore.

Asked in 1957 by the Monterey Peninsula Herald what his advice for development of Cannery Row would be, Steinbeck noted with playful exaggeration that developers could consider several possibilities: one solution might be to re-create the “new-old” of the cannery days:

A number of these buildings still stand. The purchasers might keep them as national monuments. Their tendency to rust could be halted by spraying them with plastics. Maintenance of this reminder of our historic past would, however, require that the rocks and beaches be stocked with artificial fish guts and scales. Reproducing the billions of flies that once added beauty to the scene would be difficult and costly.

But with strides in chemistry and with wind machines, the odor of rotting fish and the indescribable smell of fish meal could be wafted over the town on feast days. Perhaps this era should be kept as a monument to American know-how. For it was this forward-looking intelligence which killed all the fish, cut all the timber, thereby lowering the rainfall.

His honest solution was far better:

I suggest that these creators be allowed to look at the lovely coastline, and to design something new in the world, but something that will add to the exciting beauty rather than cancel it out…. Then tourists would not come to see a celebration of a history that never happened, an imitation of limitations, but rather a speculation on the future.

Perhaps his vision was realized in the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

In a 1953 interview, members of the Yee family, who continued to run the store until 1954 (and still own the building), were asked what question was most often put to them by tourists. Their answer: queries about Steinbeck’s Old Tennis Shoes whiskey, “We could have made a fortune if there had been a brand of whiskey named Old Tennis Shoes,” said Frances Yee.

Next to Lee Chong’s, at  851 Cannery Row, was banana-yellow Kalisa’s, another Cannery Row institution. The building was a brothel, Steinbeck’s “La Ida’s” and in fact La Ida’s Café. Kalisa Moore met Steinbeck when he came through the area in 1960 on his trip with Charley. She is memorialized with a bronze bust by Jesse Corsaut on Bruce Ariss Way.

851 Cannery Row, was banana-yellow Kalisa’s, another Cannery Row institution. The building was a brothel, Steinbeck’s “La Ida’s” and in fact La Ida’s Café. Kalisa Moore met Steinbeck when he came through the area in 1960 on his trip with Charley. She is memorialized with a bronze bust by Jesse Corsaut on Bruce Ariss Way.

The modern anchor of Cannery Row is  the Monterey Bay Aquarium, located at 886 Cannery Row. This site once was home to the Hovden Cannery, one of the first canneries to open and the last to cease operation, in 1973. With a ten-boat fleet in the halcyon years of the late 1930s and early 1940s, it was one of the largest of the area’s sixteen canneries. Stanford University bought the site—to prevent a luxury hotel from going up across from Hopkins Marine Station—and later sold it to the Packard Foundation for the aquarium that the foundation funded, and which opened, in 1984. Cannery history is eloquently and briefly told near the entrance, and the aquarium itself is a fabulous place, exhibiting marine life of Monterey Bay and beyond.Past the aquarium, along the bike and walking path that parallels Ocean View Avenue (and covers the tracks of the old Del Monte Express), the sweep of the bay overwhelms any strolling visitor. Walk here and you may become a water-gazer.

the Monterey Bay Aquarium, located at 886 Cannery Row. This site once was home to the Hovden Cannery, one of the first canneries to open and the last to cease operation, in 1973. With a ten-boat fleet in the halcyon years of the late 1930s and early 1940s, it was one of the largest of the area’s sixteen canneries. Stanford University bought the site—to prevent a luxury hotel from going up across from Hopkins Marine Station—and later sold it to the Packard Foundation for the aquarium that the foundation funded, and which opened, in 1984. Cannery history is eloquently and briefly told near the entrance, and the aquarium itself is a fabulous place, exhibiting marine life of Monterey Bay and beyond.Past the aquarium, along the bike and walking path that parallels Ocean View Avenue (and covers the tracks of the old Del Monte Express), the sweep of the bay overwhelms any strolling visitor. Walk here and you may become a water-gazer.

The Monterey Bay Aquarium, 886 Cannery Row.

Alvarado Street at Franklin, circa 1946.

Lara-Soto Adobe, 460 Pierce Street.

Several spots in Monterey retain the Steinbeck mark, and one way to see the town Steinbeck haunted is to take a walk on the “Path of History,” as indicated on maps available at the Monterey Chamber of Commerce offices in Custom House Plaza and insets in the sidewalks. The Monterey Old Town Historic District was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1970.

Most of Steinbeck’s  Alvarado Street watering holes have been replaced by the Monterey Plaza Hotel. The Keg, Johnny Garcia’s place, draws Steinbeck for a mournful drink in Travels with Charley. In 1940 he wrote part of Sea of Cortez from an office above the Wells Fargo Bank at 399 Alvarado Street. Before Doc leaves town on a collecting trip in Cannery Row, he stops to eat at Hermann’s, at 380 Alvarado, a burger joint that was open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Doc orders a hamburger (15 cents) and a beer (10 cents) and thinks about what a beer milkshake might taste like.

Alvarado Street watering holes have been replaced by the Monterey Plaza Hotel. The Keg, Johnny Garcia’s place, draws Steinbeck for a mournful drink in Travels with Charley. In 1940 he wrote part of Sea of Cortez from an office above the Wells Fargo Bank at 399 Alvarado Street. Before Doc leaves town on a collecting trip in Cannery Row, he stops to eat at Hermann’s, at 380 Alvarado, a burger joint that was open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Doc orders a hamburger (15 cents) and a beer (10 cents) and thinks about what a beer milkshake might taste like.

Steinbeck briefly owned one of Monterey’s adobes,  the Lara-Soto Adobe at 460 Pierce Street. In 1945, after a stint overseas as a war correspondent, Steinbeck brought his second wife, Gwyn, and baby Thom to live here. He wrote The Pearl in the back garden. Steinbeck wrote to his editor, Pat Covici, on October 24, 1944:

the Lara-Soto Adobe at 460 Pierce Street. In 1945, after a stint overseas as a war correspondent, Steinbeck brought his second wife, Gwyn, and baby Thom to live here. He wrote The Pearl in the back garden. Steinbeck wrote to his editor, Pat Covici, on October 24, 1944:

We bought a house in Monterey. You may think this precipitate but it is a house I have wanted since I was a little kid. It is one of the oldest and nicest adobes in town—with a huge garden—two blocks from the main street and yet unpaved and no traffic. Four blocks from the piers. It was built in the late thirties before the gold rush and is in perfect shape … it is a laughing house.

Colton Hall, 351 Pacific Street.

The Adobe at 500 Hartnell Street, behind the Monterey Public Library, was once the home of Hattie Gragg. Steinbeck loved talking to longtime residents of any community where he lived, and Hattie, one of the oldest in Monterey, loved telling stories. He visited her frequently. She told him the true story about Josh Billings, California humorist, who died at the Hotel Del Monte. Dr. J. P. Heintz from Luxembourg had an office near Hattie’s, as Steinbeck describes: “Where the new post office is, there used to be a deep gulch with water flowing in it and a little foot bridge over it. On one side of the gulch was a fine old adobe and on the other the house of the doctor who handled all the sickness, birth, and death in the town.”

The Adobe at 500 Hartnell Street, behind the Monterey Public Library, was once the home of Hattie Gragg. Steinbeck loved talking to longtime residents of any community where he lived, and Hattie, one of the oldest in Monterey, loved telling stories. He visited her frequently. She told him the true story about Josh Billings, California humorist, who died at the Hotel Del Monte. Dr. J. P. Heintz from Luxembourg had an office near Hattie’s, as Steinbeck describes: “Where the new post office is, there used to be a deep gulch with water flowing in it and a little foot bridge over it. On one side of the gulch was a fine old adobe and on the other the house of the doctor who handled all the sickness, birth, and death in the town.”

Pop Ernest’s menu.

Across the street from the Monterey Public Library, at  351 Pacific Street (with its fine local archive housed in the California Room), is Colton Hall, where California’s first constitution was debated in 1848. Adjacent to Colton Hall is the old Monterey Jail, where Danny in Tortilla Flat languished for a month, smashing bedbugs on the wall.

351 Pacific Street (with its fine local archive housed in the California Room), is Colton Hall, where California’s first constitution was debated in 1848. Adjacent to Colton Hall is the old Monterey Jail, where Danny in Tortilla Flat languished for a month, smashing bedbugs on the wall.

Old Fisherman’s Wharf, off Del Monte Boulevard, is a good place to stroll, see and hear begging sea lions, eat fried Monterey squid (a splendid snack), and take a short cruise out to see grey whales. Here “Pop” Ernest Doelter taught American diners how to eat abalone. He pounded the tough muscle into steaks for his restaurant on the Monterey wharf (and at the 1915 Pan Pacific Exposition in San Francisco). Suzy and Doc eat there in Sweet Thursday (“Pop” is Sonny Boy).

Old Fisherman’s Wharf, off Del Monte Boulevard, is a good place to stroll, see and hear begging sea lions, eat fried Monterey squid (a splendid snack), and take a short cruise out to see grey whales. Here “Pop” Ernest Doelter taught American diners how to eat abalone. He pounded the tough muscle into steaks for his restaurant on the Monterey wharf (and at the 1915 Pan Pacific Exposition in San Francisco). Suzy and Doc eat there in Sweet Thursday (“Pop” is Sonny Boy).

A menu from about 1932 notes, “Nectar of Abalone” for twenty-five cents and “All fish (fresh daily) for $.50.” Lobsters were fifty cents, seventy-five cents, and one dollar.

Steinbeck (third from left) and friends, Del Monte pier, circa 1910.

When Cannery Row was published in 1945, Steinbeck’s friend Ritch Lovejoy wrote a review of the book for the Monterey Herald, claiming in his headline that “Cannery Row is Monterey’s.” “It may be that the dreamlike quality of Steinbeck’s writing, although vivid, just cannot strike even the remotest chord of reality in the mind of a city dweller or to go a step farther, anyone as far east as the Nevada border.”

For proof of this all we have to do is to glance at the dust-cover of the book, which shows a cannery-row composed of New England landscape dotted with vague ash trees (or something) and some small skiffpiers over a lake or river where maybe men catch trout on strings with bent pin hooks, and process them in the little three story buildings along the banks.

The eastern magazines suffer a little from the same—shall we call it malady? Time magazine shows a picture of fisherman’s wharf, with a strong indication that they believe this to be “cannery row.” Newsweek magazine says that the story is about a “snug little settlement on the coast of Monterey country… inhabited by a casual assortment of human beings such as only Steinbeck could create…

You and I in Monterey… cannot well consider either fiction or fabrication Red Williams’s service station, Holman’s department story, Tom Work, Excelentisima Maria Antonia Field, Tiny Colletti (whose name is merely misspelled), “Sparky” Enea, and a few other people. In 1934, Red Williams opened a gas station at Lighthouse and

Fountain in Pacific Grove, next to Holman’s department store. Tom Work owned a lumberyard as well as many other Monterey properties. Excelentisima Maria Antonio Field, daughter of a Mexican landowner, and her brother Stevie (a friend of Steinbeck’s, mentioned in Travels with Charley) inherited a rancho on the Monterey Salinas highway, the Laguna Seca section. Maria Antonio was recognized by the King of Spain in 1933 for her work perpetuating Spanish California history. And Tiny and Sparky, fishermen, went with Steinbeck on the Sea of Cortez voyage.

Indeed, much in Cannery Row is thinly masked fact. In the novel, Dora Flood’s bouncer, William, commits suicide by plunging an ice pick through his chest. On March 6, 1933, a small piece ran in the Monterey Herald: “Self-Inflicted Wound Is Fatal.” “Plunging an ordinary ice pick into his chest just above the heart, Henry Wojciechowski, 45, former soldier, last night committed suicide at the home of Flora Woods, local night life figure.”

In his manuscript, Steinbeck wrote much of Cannery Row in the present tense, changing it to past tense in the typescript. The place lived, vividly, in his mind and heart. After being sent to Monterey in 1945 to photograph the “real” Cannery Row, Peter Stackpole remarked to his editor at Life magazine, “But Steinbeck wrote the real Cannery Row.”

Wharf #2 is the commercial wharf, where boats that were built when Steinbeck was in the area still unload their catches. Nearly at the end of the pier are two unloading stations for rock cod, sand dabs, or halibut, depending on the season. When Monterey Bay squid are in the area (hauls are irregular because squid numbers have decreased), they are unloaded at this pier, and early mornings reveal the operations that transfer tons of squid from the boats, through the weighing houses, and into waiting trucks.

Wharf #2 is the commercial wharf, where boats that were built when Steinbeck was in the area still unload their catches. Nearly at the end of the pier are two unloading stations for rock cod, sand dabs, or halibut, depending on the season. When Monterey Bay squid are in the area (hauls are irregular because squid numbers have decreased), they are unloaded at this pier, and early mornings reveal the operations that transfer tons of squid from the boats, through the weighing houses, and into waiting trucks.

Near the wharf is the Municipal Beach, now Window on the Bay—locally known by its former name,  Del Monte Beach—a wide sweep of sand where sandpipers run “as though on little wheels.” A wooden walk and then a bike path lead to the railroad stop for the Hotel Del Monte; only the platform remains. Where ladies once detrained, the descendents of Mack and the boys lounge on low walls.

Del Monte Beach—a wide sweep of sand where sandpipers run “as though on little wheels.” A wooden walk and then a bike path lead to the railroad stop for the Hotel Del Monte; only the platform remains. Where ladies once detrained, the descendents of Mack and the boys lounge on low walls.

Across from Municipal Beach is peaceful  El Estero Park and Dennis the Menace playground. Dennis’s creator, Hank Ketchum, was a member of the lab group from mid-century on.

El Estero Park and Dennis the Menace playground. Dennis’s creator, Hank Ketchum, was a member of the lab group from mid-century on.

Many of Steinbeck’s friends and characters are buried at  El Encinal Cemetery on 351 Fremont Street: Ed Ricketts, Flora Woods, Horace Bicknell (Mack), Tiny Colletto, paisanos Eduardo P. Martin (Danny) and Eduardo Romero (Pilon), Hattie Gragg, “Pop” Ernest Doelter, and Johnny Garcia.

El Encinal Cemetery on 351 Fremont Street: Ed Ricketts, Flora Woods, Horace Bicknell (Mack), Tiny Colletto, paisanos Eduardo P. Martin (Danny) and Eduardo Romero (Pilon), Hattie Gragg, “Pop” Ernest Doelter, and Johnny Garcia.

“Change was everywhere,” Steinbeck writes at the beginning of Sweet Thursday, a novel set immediately after World War II. But that melancholic strain is balanced by lighter notes; the book finds exuberance in adaptation. This is a good way to approach the Cannery Row that exists today: peel the veneer to glimpse the Cannery Row that existed for Steinbeck.