[300] The vision that follows the birth of the hero is described by Miss Miller as a “swarm of people.” We know that this image symbolizes a secret,1 or rather, the unconscious. The possession of a secret cuts a person off from his fellow human beings. Since it is of the utmost importance for the economy of the libido that his rapport with the environment should be as complete and as unimpeded as possible, the possession of subjectively important secrets usually has a very disturbing effect. It is therefore especially beneficial for the neurotic if he can at last disburden himself of his secrets during treatment. I have often noticed that the symbol of the crowd, and particularly of a streaming mass of people in motion, expresses violent motions of the unconscious. Such symbols always indicate an activation of the unconscious and an incipient dissociation between it and the ego.

[301] The vision of the swarm of people undergoes further development: horses appear, and a battle is fought.

[302] For the time being, I would like to follow Silberer and place the meaning of these visions in the “functional” category, because, fundamentally, the idea of the swarming crowd is an expression for the mass of thoughts now rushing in upon consciousness. The same is true of the battle, and possibly of the horses, which symbolize movement or energy. The deeper meaning of the horses will only become apparent in our treatment of mother-symbols. The next vision has a more definite character and a more significant content: Miss Miller sees a “dream-city.” The picture is similar to one she had seen a short time before on the cover of a magazine. Unfortunately, further details are lacking. But one can easily imagine that this dream-city is something very beautiful and ardently longed for—a kind of heavenly Jerusalem, as the poet of the Apocalypse dreamt it.2 (Cf. pl. XXIIa.)

[303] The city is a maternal symbol, a woman who harbours the inhabitants in herself like children. It is therefore understandable that the three mother-goddesses, Rhea, Cybele, and Diana, all wear the mural crown (pl. XXIVb). The Old Testament treats the cities of Jerusalem, Babylon, etc. just as if they were women. Isaiah (47 : 1ff.) cries out:

Come down, and sit in the dust, O virgin daughter of Babylon, sit on the ground: there is no throne, O daughter of the Chaldaeans: for thou shalt no more be called tender and delicate.

Take the millstones, and grind meal: uncover thy locks, make bare the leg, uncover the thigh, pass over the rivers.

Thy nakedness shall be uncovered, yea, thy shame shall be seen:

I will take vengeance, and I will not meet thee as a man.…

Sit thou silent, and get thee into darkness, O daughter of the Chaldaeans: for thou shalt no more be called, The lady of kingdoms.

[304] Jeremiah (50:12) says of Babylon:

Your mother shall be sore confounded; she that bare you shall be ashamed.

[305] Strong, unconquered cities are virgins; colonies are sons and daughters. Cities are also harlots; Isaiah (23:16) says of Tyre:

Take an harp, go about the city, thou harlot that hast been forgotten,

and (1:21):

How is the faithful city become an harlot!

[306] We find a similar symbolism in the myth of Ogyges, the prehistoric king of Egypt who reigned in Thebes, and whose wife was appropriately called Thebe. The Boeotian city of Thebes founded by Cadmus received on that account the cognomen “Ogygian.” This cognomen was also applied to the great Flood, which was called “Ogygian” because it happened under Ogyges. We shall see later on that this coincidence can hardly be accidental. The fact that the city and the wife of Ogyges both have the same name indicates that there must be some relation between the city and the woman, which is not difficult to understand because the city is identical with the woman. There is a similar idea in Hindu mythology, where Indra appears as the husband of Urvara. But Urvara means the “fertile land.” In the same way the seizure of a country by the king was regarded as his marriage with the land. Similar ideas must also have existed in Europe. Princes at their accession had to guarantee a good harvest. The Swedish king Domaldi was actually killed as a result of failure of the crops (Ynglinga Saga, 18). In the Hindu Ramayana, the hero Rama marries Sita, the furrow. To the same circle of ideas belongs the Chinese custom of the emperor’s having to plough a furrow on ascending the throne. The idea of the soil as feminine also embraces the idea of continuous cohabitation with the woman, a physical interpenetration. The god Shiva, as Mahadeva and Parvati, is both male and female: he has even given one half of his body to his wife Parvati as a dwelling-place (pl. XXIII). The motif of continuous cohabitation is expressed in the well-known lingam symbol found everywhere in Indian temples: the base is a female symbol, and within it stands the phallus.3 (P1. XXV.) This symbol is rather like the phallic baskets and chests of the Greeks. The chest or casket is a female symbol (cf. fig. 21 and pl. LIII), i.e., the womb, a common enough conception in the older mythologies.4 The chest, barrel, or basket with its precious contents was often thought of as floating on the water, thus forming an analogy to the course of the sun. The sun sails over the sea like an immortal god who every evening is immersed in the maternal waters and is born anew in the morning.

[307] Frobenius writes:

If, then, we find the blood-red sunrise connected with the idea that a birth is taking place, the birth of the young sun, the question immediately arises: Whose is the paternity? How did the woman become pregnant? And since this woman symbolizes the same idea as the fish, which means the sea (on the assumption that the sun descends into the sea as well as rises out of it), the strange primitive answer is that the sea has previously swallowed the old sun. The resulting myth is that since the sea-woman devoured the sun and now brings a new sun into the world, she obviously became pregnant in that way.5

[308] All these sea-going gods are solar figures. They are enclosed in a chest or ark for the “night sea journey” (Frobenius), often in the company of a woman (pl. XXIIb)—an inversion of the actual situation, but linking up with the theme of continuous cohabitation we met above. During the night sea journey the sun-god is shut up in the mother’s womb, and often threatened by all kinds of dangers.

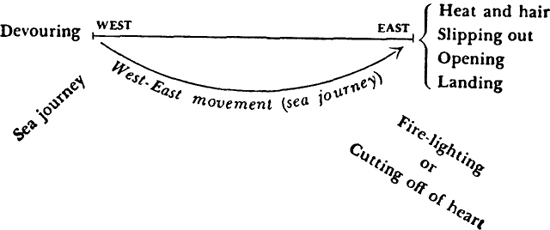

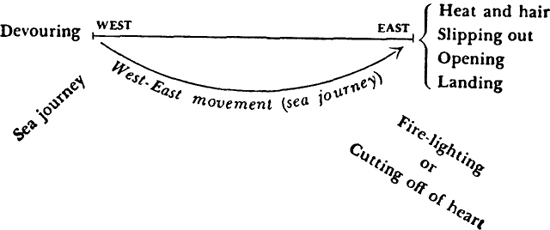

[309] Instead of using numerous separate examples, I shall content myself with reproducing the diagram which Frobenius constructed from numberless myths of this sort:

[310] Frobenius gives the following legend by way of illustration:

A hero is devoured by a water-monster in the West (devouring). The animal travels with him to the East (sea journey). Meanwhile, the hero lights a fire in the belly of the monster (fire-lighting), and feeling hungry, cuts himself a piece of the heart (cutting off of heart). Soon afterwards, he notices that the fish has glided on to dry land (landing); he immediately begins to cut open the animal from within (opening); then he slips out (slipping out). It was so hot in the fish’s belly that all his hair has fallen out (heat and hair). The hero may at the same time free all those who were previously devoured by the monster, and who now slip out too.6

[311] A very close parallel is Noah’s journey over the Flood that killed all living things; only he and his animals lived to experience a new Creation. A Polynesian myth7 tells how the hero, in the belly of Kombili, the King Fish, seized his obsidian knife and cut open the fish’s belly. “He slipped out and beheld a splendour. Then he sat down and began to think. ‘I wonder where I am?’ he said to himself. Then the sun rose up with a bound and threw itself from one side to the other.” The sun had again slipped out. Frobenius cites from the Ramayana the story of the ape Hanuman, who represents the sun-hero:

The sun, travelling through the air with Hanuman in it, cast a shadow on the sea, a sea-monster seized hold of it and drew Hanuman down from the sky. But when Hanuman saw that the monster was about to devour him, he stretched himself out to enormous size, and the monster followed suit. Then Hanuman shrank to the size of a thumb, slipped into the huge body of the monster, and came out on the other side.7a Hanuman thereupon resumed his flight, and encountered a new obstacle in another sea monster, who was the mother of Rahu, the sun-devouring demon. She also drew Hanuman down to her by his shadow.8 Once more he had recourse to his earlier stratagem, made himself small, and slipped into her body; but scarcely was he inside than he swelled up to gigantic size, burst her, and killed her, and so made his escape.9

We now understand why the Indian fire-bringer Matarisvan is called “he who swells in the mother.” The ark (fig. 21), chest, casket, barrel, ship, etc. is an analogy of the womb, like the sea into which the sun sinks for rebirth. That which swells in the mother can also signify her conquest and death. Fire-making is a pre-eminently conscious act and therefore “kills” the dark state of union with the mother.

[312] In the light of these ideas we can understand the mythological statements about Ogyges: it is he who possesses the mother, the city, and is thus united with the mother; therefore under him came the great flood, for it is typical of the sun myth that the hero, once he is united with the woman “hard to attain,” is exposed in a cask and thrown out to sea, and then lands on a distant shore to begin a new life. The middle section, the night sea journey in the ark, is lacking in the Ogyges tradition. But the rule in mythology is that the typical parts of a myth can be fitted together in every conceivable variation, which makes it extraordinarily difficult to interpret one myth without a knowledge of all the others. The meaning of this cycle of myths is clear enough: it is the longing to attain rebirth through a return to the womb, and to become immortal like the sun. This longing for the mother is amply expressed in the literature of the Bible. I cite first the passage in Galatians 4 : 26ff. and 5:1:

Fig. 21. Noah in the Ark

Enamelled altar of Nicholas of Verdun, 1186,

Klosterneuburg, near Vienna

But Jerusalem which is above is free, which is the mother of us all.

For it is written, Rejoice, thou barren that bearest not; break forth and cry, thou that travailest not: for the desolate hath many more children than she which hath an husband.

Now we, brethren, as Isaac was, are the children of promise.

But as then he that was born after the flesh persecuted him that was born after the Spirit, even so it is now.

Nevertheless what saith the scripture? Cast out the bondwoman and her son: for the son of the bondwoman shall not be heir with the son of the freewoman.

So then, brethren, we are not children of the bondwoman, but of the free.

Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free …

[313] The Christians are children of the Higher City, not sons of the earthly city-mother, who is to be cast out; for those born after the flesh are opposed to those born after the spirit, who are not born from the fleshly mother but from a symbol of the mother. Here again one thinks of the American Indians who say that the first man was born from a sword-hilt and a shuttle. The symbol-creating process substitutes for the mother the city, the well, the cave, the Church, etc. (Cf. pls. XXIIa, XXXa.) This substitution is due to the fact that the regression of libido reactivates the ways and habits of childhood, and above all the relation to the mother;10 but what was natural and useful to the child is a psychic danger for the adult, and this is expressed by the symbol of incest. Because the incest taboo opposes the libido and blocks the path to regression, it is possible for the libido to be canalized into the mother analogies thrown up by the unconscious. In that way the libido becomes progressive again, and even attains a level of consciousness higher than before. The meaning and purpose of this canalization are particularly evident when the city appears in place of the mother: the infantile attachment (whether primary or secondary) is a crippling limitation for the adult, whereas attachment to the city fosters his civic virtues and at least enables him to lead a useful existence. In primitives the tribe takes the place of the city. We find a well-developed city symbolism in the Johannine Apocalypse, where two cities play a great part, one being cursed and execrated, the other ardently desired. We read in the Revelation (17 : 1ff.):

Come hither; I will show unto thee the judgement of the great whore that sitteth upon many waters:

With whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication, and the inhabitants of the earth have been made drunk with the wine of her fornication.

So he carried me away in the spirit into the wilderness: and I saw a woman sit upon a scarlet coloured beast, full of names of blasphemy, having seven heads and ten horns.

And the woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet colour, and decked with gold and precious stones and pearls, having a golden cup in her hand full of abominations and filthiness of her fornication:

And upon her forehead was a name written: Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth.

And I saw the woman drunken with the blood of the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus: and when I saw her, I wondered with a great admiration. [Fig. 22.]

[314] There now follows a barely intelligible interpretation of the vision, the main points of interest being that the seven heads of the dragon signify “seven mountains, on which the woman sitteth.” This is probably a direct allusion to Rome, the city whose temporal power oppressed the world at that time. “The waters where the whore [the mother] sitteth” are “peoples, and multitudes, and nations, and tongues,” and this too seems to refer to Rome, for she is the mother of peoples and possesses all lands. Just as colonies are called “daughters,” so the peoples subject to Rome are like members of a family ruled over by the mother. In another scene the kings of the earth, i.e., the “sons,” commit fornication with her. The Apocalypse continues (18:2ff.):

Babylon the great is fallen, is fallen, and is become the habitation of devils, and the hold of every foul spirit, and a cage of every unclean and hateful bird.

For all nations have drunk of the wine of the wrath of her fornication, and the kings of the earth have committed fornication with her.

[315] This mother, then, is not only the mother of all abominations, but the receptacle of all that is wicked and unclean. The birds are soul-images,11 by which are meant the souls of the damned and evil spirits. Thus the mother becomes the underworld, the City of the Damned. In this primordial image of the woman on the dragon12 we recognize Echidna, the mother of every hellish horror. Babylon is the symbol of the Terrible Mother, who leads the peoples into whoredom with her devilish temptations and makes them drunk with her wine (cf. fig. 22). Here the intoxicating drink is closely associated with fornication, for it too is a libido symbol, as we have already seen in the soma-fire-sun parallel.

Fig. 22. The Great Whore of Babylon

New Testament engraving by H. Burgkmaier, Augsburg, l523

[316] After the fall and curse of Babylon, we find the hymn (Rev. 19 : 6ff.) which brings us from the lower half of the mother to the upper half, where everything that incest would have made impossible now becomes possible:

Alleluia: for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth.

Let us be glad and rejoice, and give honour to him: for the marriage of the Lamb13 is come, and his wife hath made herself ready.

And to her was granted that she should be arrayed in fine linen, clean and white: for the fine linen is the righteousness of saints.

And he saith unto me, Write, Blessed are they which are called unto the marriage supper of the Lamb.

[317] The Lamb is the Son of Man who celebrates his nuptials with the “woman.” Who the “woman” is remains obscure at first, but Rev. 21:9ff. shows us which “woman” is the bride, the Lamb’s wife:

Come hither, I will show thee the bride, the Lamb’s wife.14

And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and showed me that great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God. [Cf. pl. XXIIa.]

[318] After all that has gone before, it is evident from this passage that the City, the heavenly bride who is here promised to the Son, is the mother or mother-imago.15 In Babylon the impure maid was cast out, according to Galatians, in order that the mother-bride might be the more surely attained in the heavenly Jerusalem. It is proof of the most delicate psychological perception that the Church Fathers who compiled the canon did not allow the Apocalypse to get lost, for it is a rich mine of primitive Christian symbols.16 The other attributes that are heaped on the heavenly Jerusalem put its mother significance beyond doubt (Rev. 22:1f.):

And he showed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb.

In the midst of the street of it, and on either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits, and yielded her fruit every month: and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.

And there shall be no more curse.

[319] In this passage we meet the water-symbol which we found connected with the city in the case of Ogyges. The maternal significance of water (pl. XXVI) is one of the clearest interpretations of symbols in the whole field of mythology,17 so that even the ancient Greeks could say that “the sea is the symbol of generation.” From water comes life;18 hence, of the two deities who here interest us most, Christ and Mithras, the latter is represented as having been born beside a river, while Christ experienced his “rebirth” in the Jordan. Christ, moreover, was born of the Πηγή,19 the sempiternal fons amoris or Mother of God, whom pagan-Christian legend turned into a nymph of the spring. The spring is also found in Mithraism. A Pannonian dedication reads “Fonti perenni.” An inscription from Apulum is dedicated to the “Fons aeternus.”20 In Persian, Ardvisura is the fount of the water of life. Ardvisura-Anahita is a goddess of water and love (just as Aphrodite is the “foam-born”). In the Vedas, the waters are called malritamah, ‘most maternal.’ All living things rise, like the sun, from water, and sink into it again at evening. Born of springs, rivers, lakes, and seas, man at death comes to the waters of the Styx, and there embarks on the “night sea journey.” Those black waters of death are the water of life, for death with its cold embrace is the maternal womb, just as the sea devours the sun but brings it forth again. Life knows no death; as the Spirit says in Faust:

In flood of life, in action’s storm

I ply on my wave

With weaving motion

Birth and the grave,

A boundless ocean,

Weft of living,

Forms unending,

Glowing and blending.…21

[320] The projection of the mother-imago upon water endows the latter with a number of numinous or magical qualities peculiar to the mother. A good example of this is the baptismal water symbolism in the Church (pl. XXVII). In dreams and fantasies the sea or a large expanse of water signifies the unconscious. The maternal aspect of water coincides with the nature of the unconscious, because the latter (particularly in men) can be regarded as the mother or matrix of consciousness. Hence the unconscious, when interpreted on the subjective level,22 has the same maternal significance as water.

[321] Another equally common mother-symbol is the wood of life (ξύλον ζωή ), or tree of life. The tree of life may have been, in the first instance, a fruit-bearing genealogical tree, and hence a kind of tribal mother. Numerous myths say that human beings came from trees, and many of them tell how the hero was enclosed in the maternal tree-trunk, like the dead Osiris in the cedar-tree, Adonis in the myrtle, etc. (Cf. fig. 23.) Numerous female deities were worshipped in tree form, and this led to the cult of sacred groves and trees. Hence when Attis castrates himself under a pine-tree, he did so because the tree has a maternal significance. Juno of Thespiae was a bough, Juno of Samos a plank, Juno of Argos a pillar, the Carian Diana was an unhewn block of wood, Athene of Lindus a polished column.23 Tertullian called the Ceres of Pharos “rudis palus et informe lignum sine effigie” (a rough and shapeless wooden stake with no face). Athenaeus remarks that the Latona at Delos was ξὺλινον ᾂμορϕον, ‘an amorphous bit of wood.’ Tertullian also describes an Attic Pallas as a “crucis stipes” (cross-post). The naked wooden pole, as the name itself indicates (

), or tree of life. The tree of life may have been, in the first instance, a fruit-bearing genealogical tree, and hence a kind of tribal mother. Numerous myths say that human beings came from trees, and many of them tell how the hero was enclosed in the maternal tree-trunk, like the dead Osiris in the cedar-tree, Adonis in the myrtle, etc. (Cf. fig. 23.) Numerous female deities were worshipped in tree form, and this led to the cult of sacred groves and trees. Hence when Attis castrates himself under a pine-tree, he did so because the tree has a maternal significance. Juno of Thespiae was a bough, Juno of Samos a plank, Juno of Argos a pillar, the Carian Diana was an unhewn block of wood, Athene of Lindus a polished column.23 Tertullian called the Ceres of Pharos “rudis palus et informe lignum sine effigie” (a rough and shapeless wooden stake with no face). Athenaeus remarks that the Latona at Delos was ξὺλινον ᾂμορϕον, ‘an amorphous bit of wood.’ Tertullian also describes an Attic Pallas as a “crucis stipes” (cross-post). The naked wooden pole, as the name itself indicates ( áλη

áλη , palus, Pfahl, pale, pile), is phallic (cf. pl. XXVIII). The ϕαλλóς is a pole, a ceremonial lingam carved out of figwood, as are all the Roman statues of Priapus. Φáλο

, palus, Pfahl, pale, pile), is phallic (cf. pl. XXVIII). The ϕαλλóς is a pole, a ceremonial lingam carved out of figwood, as are all the Roman statues of Priapus. Φáλο means the peak or ridge of a helmet, later called κῶνο

means the peak or ridge of a helmet, later called κῶνο , ‘cone.’ Φáλληνοs (from ϕαλλós) means ‘wooden’; øaλ-áγγωμa is a cylinder; øáλaγξ, a round beam. The Macedonian shock-troops when drawn up in battle array were also known as a phalanx, and so is the finger-joint.24 Finally, we have to consider øαλó

, ‘cone.’ Φáλληνοs (from ϕαλλós) means ‘wooden’; øaλ-áγγωμa is a cylinder; øáλaγξ, a round beam. The Macedonian shock-troops when drawn up in battle array were also known as a phalanx, and so is the finger-joint.24 Finally, we have to consider øαλó , ‘bright, shining.’ The Indo-European root is *bhale, ‘to bulge, swell.’25 Who does not think of Faust’s “It glows, it shines, increases in my hand!”26

, ‘bright, shining.’ The Indo-European root is *bhale, ‘to bulge, swell.’25 Who does not think of Faust’s “It glows, it shines, increases in my hand!”26

[322] This is “primitive” libido symbolism, which shows how direct is the connection between libido and light. We find much the same thing in the invocations to Rudra in the Rig-Veda:

May we obtain favour of thee, O ruler of heroes, maker of bountiful water [i.e., urine].…

We call down for our help the fiery Rudra, who fulfils the sacrifice, the seer who circles in the sky.…

He who yields sweetness, who hears our invocations, the ruddy-hued with the gorgeous helm, let him not deliver us into the power of jealousy.

The bull of the Marut has gladdened me, the suppliant, with more vigorous health.…

Let a great hymn of praise resound to the ruddy-brown bull, the white-shining (sun); let us worship the fiery god with prostrations; let us sing of the glorious being of Rudra.

May the arrow of Rudra be turned from us; may the anger of the fiery god pass us by. Unbend thy firm bow (?) for the princes; thou who blessest with the waters of thy body, be gracious to our children and grandchildren.27

[323] Here the various aspects of the psychic life-force, of the extraordinarily potent,” the personified mana-concept, come together in the figure of Rudra: the fiery-white sun, the gorgeous helm, the puissant bull, and the urine (urere, ‘to burn’).

[324] Not only the gods, but the goddesses, too, are libido-symbols, when regarded from the point of view of their dynamism. The libido expresses itself in images of sun, light, fire, sex, fertility, and growth. In this way the goddesses, as we have seen, come to possess phallic symbols, even though the latter are essentially masculine. One of the main reasons for this is that, just as the female lies hidden in the male (pl. XXIX), so the male lies hidden in the female.28 The feminine quality of the tree that represents the goddess (cf. pl. XXXI) is contaminated with phallic symbolism, as is evident from the genealogical tree that grows out of Adam’s body. In my Psychology and Alchemy I have reproduced, from a manuscript in Florence, a picture of Adam showing the membrum υirile as a tree.29 Thus the tree has a bisexual character, as is also suggested by the fact that in Latin the names of trees have masculine endings and the feminine gender.30

[325] The tree in the following dream of a young woman patient brings out this hermaphroditism:31 She was in a garden, where she found an exotic-looking tree with strange red fleshy flowers or fruits. She picked and ate them. Then, to her horror, she felt that she was poisoned.

[326] As a result of sexual difficulties in her marriage, the dreamer’s fancy had been much taken by a certain young man of her acquaintance. The tree is the same tree that stood in Paradise, and it plays the same role in this dream as it did for our first parents. It is the tree of libido, which here represents the feminine as well as the masculine side, because it simply expresses the relationship of the two to one another.

[327] A Norwegian riddle runs:

A tree stands on the Billinsberg,

Drooping over a lake.

Its branches shine like gold.

You won’t guess that today.

[328] In the evening the sun’s daughter collects the golden branches that have dropped from the wonderful oak.

Bitterly weeps the sun-child

In the apple orchard.

From the apple-tree has fallen

The golden apple.

Weep not, sun-child,

God will make another

Of gold or bronze,

Or a little silver one.

[329] The various meanings of the tree—sun, tree of Paradise, mother, phallus—are explained by the fact that it is a libido-symbol and not an allegory of this or that concrete object. Thus a phallic symbol does not denote the sexual organ, but the libido, and however clearly it appears as such, it does not mean itself but is always a symbol of the libido. Symbols are not signs or allegories for something known; they seek rather to express something that is little known or completely unknown. The tertium comparationis for all these symbols is the libido, and the unity of meaning lies in the fact that they are all analogies of the same thing. In this realm the fixed meaning of things comes to an end. The sole reality is the libido, whose nature we can only experience through its effect on us. Thus it is not the real mother who is symbolized, but the libido of the son, whose object was once the mother. We take mythological symbols much too concretely and are puzzled at every turn by the endless contradictions of myths. But we always forget that it is the unconscious creative force which wraps itself in images. When, therefore, we read: “His mother was a wicked witch,” we must translate it as: the son is unable to detach his libido from the mother-imago, he suffers from resistances because he is tied to the mother.

[330] The water and tree symbolism, which we found as further attributes of the symbol of the city, likewise refer to the libido that is unconsciously attached to the mother-imago. In certain passages of the Apocalypse we catch a clear glimpse of this longing for the mother.32 Also, the author’s eschatological expectations end with the mother: “And there shall be no more curse.” There shall be no more sin, no more repression, no more disharmony with oneself, no guilt, no fear of death and no pain of separation, because through the marriage of the Lamb the son is united with the mother-bride and the ultimate bliss is attained. This symbol recurs in the nuptiae chymicae, the coniunctio of alchemy.33

[331] Thus the Apocalypse dies away on that same note of radiant, mystic harmony which was re-echoed some two thousand years later in the last prayer of “Doctor Marianus”:

O contrite hearts, seek with your eyes

The visage of salvation;

Blissful in that gaze, arise

Through glad regeneration.

Now may every pulse of good

Seek to serve before thy face,

Virgin, Queen of Motherhood,

Keep us, Goddess, in thy grace.34

[332] The beauty and nobility of these feelings raises in our minds a question of principle: is the causal interpretation of Freud correct in believing that symbol-formation is to be explained solely by prevention of the primary incest tendency, and is thus a mere substitute product? The so-called “incest prohibition” which is supposed to operate here is not in itself a primary phenomenon, but goes back to something much more fundamental, namely the primitive system of marriage classes which, in its turn, is a vital necessity in the organization of the tribe. So it is more a question of phenomena requiring a teleological explanation than of simple causalities. Moreover it must be pointed out that the basis of the “incestuous” desire is not cohabitation, but, as every sun myth shows, the strange idea of becoming a child again, of returning to the parental shelter, and of entering into the mother in order to be reborn through her. But the way to this goal lies through incest, i.e., the necessity of finding some way into the mother’s body. One of the simplest ways would be to impregnate the mother and beget oneself in identical form all over again. But here the incest prohibition intervenes; consequently the sun myths and rebirth myths devise every conceivable kind of mother-analogy for the purpose of canalizing the libido into new forms and effectively preventing it from regressing to actual incest. For instance, the mother is transformed into an animal, or is made young again,35 and then disappears after giving birth, i.e., is changed back into her old shape. It is not incestuous cohabitation that is desired, but rebirth. The incest prohibition acts as an obstacle and makes the creative fantasy inventive; for instance, there are attempts to make the mother pregnant by means of fertility magic. The effect of the incest-taboo and of the attempts at canalization is to stimulate the creative imagination, which gradually opens up possible avenues for the self-realization of libido. In this way the libido becomes imperceptibly spiritualized. The power which “always desires evil” thus creates spiritual life. That is why the religions exalt this procedure into a system. It is instructive to see the pains they take to further the translation into symbols.36 The New Testament gives us an excellent example of this: in the dialogue about rebirth (John 3:4ff.), Nicodemus cannot help taking the matter realistically:

How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born?

[333] Jesus tries to purify the sensuous cast of Nicodemus’ mind by rousing it from its dense materialistic slumbers, and translates the passage into the same, and yet not the same, words:

Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.

That which is born of flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit.

Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again.

The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.

[334] To be born of water simply means to be born of the mother’s womb; to be born of the Spirit means to be born of the fructifying breath of the wind, as can be seen from the Greek text of the passages italicized above, where spirit and wind are expressed by the same word, are expressed by the same word, πνεῡμα: “τò γεγεννημένον ἐκ τῆs σαρκòs σáρξ ἐστιν, καì τò γεγννημένον ἐκ τοῡ πνεὑματοs πνεῡμá ἐστιν.… Tò πνεῡμα ὅπου θἑλει πνεῑ.”

[335] This symbolism arose from the same need as that which produced the Egyptian legend of the vultures: they were female only and were fertilized by the wind. The basis of these mythological statements is an ethical demand which can be formulated thus: you should not say that your mother is impregnated by a man in the ordinary way, but is impregnated in some extraordinary way by a spiritual being. As this stands in complete contrast to the empirical truth, the myth bridges over the difficulty by analogy: the son is said to have been a hero who died, was born again in a remarkable manner, and thus attained to immortality. The need responsible for this demand is evidently a desire to transcend reality. A son may naturally believe that a father begot him in the flesh, but not that he himself can impregnate his mother and so cause himself to be born young again. Such a thought is prohibited by the danger of regression, and is therefore replaced by the above demand that one should, in certain circumstances, express the problem of rebirth in symbolical terms. We see the same thing in Jesus’ challenge to Nicodemus: Do not think carnally, or you will be flesh, but think symbolically, and then you will be spirit. It is evident that this compulsion towards the symbolical is a great educative force, for Nicodemus would remain stuck in banalities if he did not succeed in raising himself above his concretism. Had he been a mere Philistine, he would certainly have taken offence at the irrationality and unreality of this advice and understood it literally, only to reject it in the end as impossible and incomprehensible. The reason why Jesus’ words have such great suggestive power is that they express the symbolical truths which are rooted in the very structure of the human psyche. The empirical truth never frees a man from his bondage to the senses; it only shows him that he was always so and cannot be otherwise. The symbolical truth, on the other hand, which puts water in place of the mother and spirit or fire in place of the father, frees the libido from the channel of the incest tendency, offers it a new gradient, and canalizes it into a spiritual form. Thus man, as a spiritual being, becomes a child again and is born into a circle of brothers and sisters: but his mother has become the “communion of saints,” the Church (pl. XXXa), and his brothers and sisters are humanity, with whom he is united anew in the common heritage of symbolical truth. It seems that this process was especially necessary at the time when Christianity originated; for that age, as a result of the appalling contrast between slavery and the freedom of the citizens and masters, had entirely lost consciousness of the unity of mankind.

[336] When we see how much trouble Jesus took to make the symbolical view of things acceptable to Nicodemus, as if throwing a veil over the crude reality, and how important it was—and still is—for the history of civilization that people should think in this way, then one is at a loss to understand why the concern of modern psychology with symbolism has met with such violent disapprobation in many quarters. It is as necessary today as it ever was to lead the libido away from the cult of rationalism and realism—not, indeed, because these things have gained the upper hand (quite the contrary), but because the guardians and custodians of symbolical truth, namely the religions, have been robbed of their efficacy by science. Even intelligent people no longer understand the value and purpose of symbolical truth, and the spokesmen of religion have failed to deliver an apologetic suited to the spirit of the age. Insistence on the bare concretism of dogma, or ethics for ethics’ sake, or even a humanization of the Christ-figure coupled with inadequate attempts to write his biography, are singularly unimpressive. Symbolical truth is exposed undefended to the attacks of scientific thought, which can never do justice to such a subject, and in face of this competition has been unable to hold its ground. The truth, however, still remains to be proved. Exclusive appeals to faith are a hopeless petitio principii, for it is the manifest improbability of symbolical truth that prevents people from believing in it. Instead of insisting so glibly on the necessity of faith, the theologians, it seems to me, should see what can be done to make this faith possible. But that means placing symbolical truth on a new foundation—a foundation which appeals not only to sentiment, but to reason. And this can only be achieved by reflecting how it came about in the first place that humanity needed the improbability of religious statements, and what it signifies when a totally different spiritual reality is superimposed on the sensuous and tangible actuality of this world.

[337] The instincts operate most smoothly when there is no consciousness to conflict with them, or when what consciousness there is remains firmly attached to instinct. This condition no longer applies even to primitive man, for everywhere we find psychic systems at work which are in some measure opposed to pure instinctuality. And if a primitive tribe shows even the smallest traces of culture, we find that creative fantasy is continually engaged in producing analogies to instinctual processes in order to free the libido from sheer instinctuality by guiding it towards analogical ideas. These systems have to be constituted in such a way that they offer the libido a kind of natural gradient. For the libido does not incline to anything, otherwise it would be possible to turn it in any direction one chose. But that is the case only with voluntary processes, and then only to a limited degree. The libido has, as it were, a natural penchant: it is like water, which must have a gradient if it is to flow. The nature of these analogies is therefore a serious problem because, as we have said, they must be ideas which attract the libido. Their special character is, I believe, to be discerned in the fact that they are archetypes, that is, universal and inherited patterns which, taken together, constitute the structure of the unconscious. When Christ, for instance, speaks to Nicodemus of spirit and water, these are not just random ideas, but typical ones which have always exerted a powerful fascination on the mind. Christ is here touching on the archetype, and that, if anything, will convince Nicodemus, for the archetypes are the forms or river-beds along which the current of psychic life has always flowed.

[338] It is not possible to discuss the problem of symbol-formation without reference to the instinctual processes, because it is from them that the symbol derives its motive power. It has no meaning whatever unless it strives against the resistance of instinct, just as undisciplined instincts would bring nothing but ruin to man if the symbol did not give them form. Hence a discussion of one of the strongest instincts, sexuality, is unavoidable, since perhaps the majority of symbols are more or less close analogies of this instinct. To interpret symbol-formation in terms of instinctual processes is a legitimate scientific attitude, which does not, however, claim to be the only possible one. I readily admit that the creation of symbols could also be explained from the spiritual side, but in order to do so, one would need the hypothesis that the “spirit” is an autonomous reality which commands a specific energy powerful enough to bend the instincts round and constrain them into spiritual forms. This hypothesis has its disadvantages for the scientific mind, even though, in the end, we still know so little about the nature of the psyche that we can think of no decisive reason against such an assumption. In accordance with my empirical attitude I nevertheless prefer to describe and explain symbol-formation as a natural process, though I am fully conscious of the probable one-sidedness of this point of view.

[339] As we have said, sex plays an important part in this process, even when the symbols are religious. It is less than two thousand years since the cult of sex was in full bloom. In those days, of course, they were heathens and did not know any better, but the nature of the symbol-creating forces does not change from age to age. If one has any conception of the sexual content of those ancient cults, and if one realizes that the experience of union with God was understood in antiquity as a more or less concrete coitus, then one can no longer pretend that the forces motivating the production of symbols have suddenly become different since the birth of Christ. The fact that primitive Christianity resolutely turned away from nature and the instincts in general, and, through its asceticism, from sex in particular, clearly indicates the source from which its motive forces came. So it is not surprising that this transformation has left noticeable traces in Christian symbolism. Had it not done so, Christianity would never have been able to transform libido. It succeeded in this largely because its archetypal analogies were for the most part in tune with the instinctual forces it wanted to transform. Some people profess to be very shocked when I do not shrink from bringing even the sublimest spiritual ideas into relation with what they call the “subhuman.” My primary concern, however, is to understand these religious ideas, whose value I appreciate far too deeply to dispose of them with rationalistic arguments. What do we want, anyway, with things that cannot be understood? They appeal only to people for whom thinking and understanding are too much bother. Instead, we ask for blind faith and praise it to the skies. But that, in the end, only means educating ourselves to thoughtlessness and lack of criticism. What the “blind faith” so long preached from the pulpit was able to do in Germany, when that country finally turned its back on Christian dogma, has been bloodily demonstrated before our eyes by contemporary history. The really dangerous people are not the great heretics and unbelievers, but the swarm of petty thinkers, the rationalizing intellectuals, who suddenly discover how irrational all religious dogmas are. Anything not understood is given short shrift, and the highest values of symbolic truth are irretrievably lost. What can a rationalist do with the dogma of the virgin birth, or with Christ’s sacrificial death, or the Trinity?

[340] The medical psychotherapist today must make clear to his more educated patients the foundations of religious experience, and set them on the road to where such an experience becomes possible. If, therefore, as a doctor and scientist, I analyse abstruse religious symbols and trace them back to their origins, my sole purpose is to conserve, through understanding, the values they represent, and to enable people to think symbolically once more, as the early thinkers of the Church were still able to do. This is far from implying an arid dogmatism. It is only when we, today, think dogmatically, that our thought becomes antiquated and no longer accessible to modern man. Hence a way has to be found which will again make it possible for him to participate spiritually in the substance of the Christian message.

[341] At a time when a large part of mankind is beginning to discard Christianity, it may be worth our while to try to understand why it was accepted in the first place. It was accepted as a means of escape from the brutality and unconsciousness of the ancient world. As soon as we discard it, the old brutality returns in force, as has been made overwhelmingly clear by contemporary events. This is not a step forwards, but a long step backwards into the past. It is the same with individuals who lay aside one form of adaptation and have no new form to turn to: they infallibly regress along the old path and then find themselves at a great disadvantage, because the world around them has changed considerably in the meantime. Consequently, any one who is repelled by the philosophical weakness of Christian dogmatism or by the barren idea of a merely historical Jesus—for we know far too little about his contradictory personality and the little we do know only confuses our judgment—and who throws Christianity overboard and with it the whole basis of morality, is bound to be confronted with the age-old problem of brutality. We have had bitter experience of what happens when a whole nation finds the moral mask too stupid to keep up. The beast breaks loose, and a frenzy of demoralization sweeps over the civilized world.37

[342] Today there are countless neurotics who are neurotic simply because they do not know why they cannot be happy in their own way—they do not even know that the fault lies with them. Besides these neurotics there are many more normal people, men and women of the better kind, who feel restricted and discontented because they have no symbol which would act as an outlet for their libido. For all these people a reductive analysis down to the primal facts should be undertaken, so that they can become acquainted with their primitive personality and learn how to take due account of it. Only in this way can certain requirements be fulfilled and others rejected as unreasonable because of their infantile character. We like to imagine that our primitive traits have long since disappeared without trace. In this we are cruelly disappointed, for never before has our civilization been so swamped with evil. This gruesome spectacle helps us to understand what Christianity was up against and what it endeavoured to transform. The transforming process took place for the most part unconsciously, at any rate in the later centuries. When I remarked earlier (par. 106) that an unconscious transformation of libido was ethically worthless, and contrasted it with the Christianity of the early Roman period, as a patent example of the immorality and brutalization against which Christians had to fight, I ought to have added that mere faith cannot be counted as an ethical ideal either, because it too is an unconscious transformation of libido. Faith is a charisma for those who possess it, but it is no way for those who need to understand before they can believe. This is a matter of temperament and cannot be discounted as valueless. For, ultimately, even the believer believes that God gave man reason, and for something better than to lie and cheat with. Although we naturally believe in symbols in the first place, we can also understand them, and this is indeed the only viable way for those who have not been granted the charisma of faith.

[343] The religious myth is one of man’s greatest and most significant achievements, giving him the security and inner strength not to be crushed by the monstrousness of the universe. Considered from the standpoint of realism, the symbol is not of course an external truth, but it is psychologically true, for it was and is the bridge to all that is best in humanity.38

[344] Psychological truth by no means excludes metaphysical truth, though psychology, as a science, has to hold aloof from all metaphysical assertions. Its subject is the psyche and its contents. Both are realities, because they work. Though we do not possess a physics of the soul, and are not even able to observe it and judge it from some Archimedean point “outside” ourselves, and can therefore know nothing objective about it since all knowledge of the psyche is itself psychic, in spite of all this the soul is the only experient of life and existence. It is, in fact, the only immediate experience we can have and the sine qua non of the subjective reality of the world. The symbols it creates are always grounded in the unconscious archetype, but their manifest forms are moulded by the ideas acquired by the conscious mind. The archetypes are the numinous, structural elements of the psyche and possess a certain autonomy and specific energy which enables them to attract, out of the conscious mind, those contents which are best suited to themselves. The symbols act as transformers, their function being to convert libido from a “lower” into a “higher” form. This function is so important that feeling accords it the highest values. The symbol works by suggestion; that is to say, it carries conviction and at the same time expresses the content of that conviction. It is able to do this because of the numen, the specific energy stored up in the archetype. Experience of the archetype is not only impressive, it seizes and possesses the whole personality, and is naturally productive of faith.

[345] “Legitimate” faith must always rest on experience. There is, however, another kind of faith which rests exclusively on the authority of tradition. This kind of faith could also be called “legitimate,” since the power of tradition embodies an experience whose importance for the continuity of culture is beyond question. But with this kind of faith there is always the danger of mere habit supervening—it may so easily degenerate into spiritual inertia and a thoughtless compliance which, if persisted in, threatens stagnation and cultural regression. This mechanical dependence goes hand in hand with a psychic regression to infantilism. The traditional contents gradually lose their real meaning and are only believed in as formalities, without this belief having any influence on the conduct of life. There is no longer a living power behind it. The much-vaunted “child-likeness” of faith only makes sense when the feeling behind the experience is still alive. If it gets lost, faith is only another word for habitual, infantile dependence, which takes the place of, and actually prevents, the struggle for deeper understanding. This seems to be the position we have reached today.

[346] Since faith revolves round those central and perennially important “dominant ideas” which alone give life a meaning, the prime task of the psychotherapist must be to understand the symbols anew, and thus to understand the unconscious, compensatory striving of his patient for an attitude that reflects the totality of the psyche.

[347] After this digression, let us return to our author.

[348] The vision of the city is immediately followed by that of a “strange conifer with knotty branches.” This image no longer seems strange to us after what we have learned about the tree of life and its association with the mother, the city, and the water of life. The attribute “strange” probably expresses, as in dreams, a peculiar emphasis or numinosity. Unfortunately the author gives us no individual material in this connection. As the tree already suggested in the symbolism of the city is specially emphasized in the further development of the visions, I feel it necessary to discuss at some length the history of tree symbolism.

[349] Trees, as is well known, have played a large part in religion and in mythology from the remotest times. (Pl. XXXI.) Typical of the trees found in myth is the tree of paradise, or tree of life; most people know of the pine-tree of Attis, the tree or trees of Mithras, and the world-ash Yggdrasill of Nordic mythology, and so on. The hanging of Attis, in effigy, on a pine-tree (cf. fig. 42), the hanging of Marsyas, which became a popular theme for art, the hanging of Odin, the Germanic hanging sacrifices and the whole series of hanged gods—all teach us that the hanging of Christ on the Cross is nothing unique in religious mythology, but belongs to the same circle of ideas. In this world of images the Cross is the Tree of Life and at the same time a Tree of Death—a coffin (cf. pl. XXXVI). Just as the myths tell us that human beings were descended from trees, so there were burial customs in which people were buried in hollow tree-trunks, whence the German Totenbaum, ‘tree of death,’ for coffin, which is still in use today. If we remember that the tree is predominantly a mother-symbol, then the meaning of this mode of burial becomes clear. The dead are delivered back to the mother for rebirth. (Cf. fig. 23 and pl. XLII.) We meet this symbol in the myth of Osiris as handed down by Plutarch.39 Rhea was pregnant with Osiris and his twin sister Isis, and they mated together even in their mother’s womb (night sea journey with incest). Their son was Arueris, later called Horus. Isis is said to have been “born in the All-Wetness” (ἐν πανὐγρoιs γενέσθaι), and of Osiris it is related that a certain Pamyles of Thebes, whilst drawing water, heard a voice from the temple of Zeus which commanded him to proclaim that Osiris, “the great and beneficent king” (μέγas βaσλεὐs εὐεργέτηs), was born. In honour of this Pamyles the Pamylia were celebrated, similar to the Phallophoria. Pamyles seems, therefore, to have been originally a phallic daimon, like Dionysus. In his phallic form he represents the creative power which “draws” things out of the unconscious (i.e., the water) and begets the god (Osiris) as a conscious content. This process can be understood both as an individual experience: Pamyles drawing water, and as a symbolic act or experience of the archetype: a drawing up from the depths. What is drawn up is a numinous, previously unconscious content which would remain dark were it not interpreted by the voice from above as the birth of a god. This type of experience recurs in the baptism in the Jordan, Matthew 3:17.

[350] Osiris was killed in a crafty manner by the god of the underworld, Set (Typhon in Greek), who locked him in a chest. He was thrown into the Nile and carried out to sea. But in the underworld Osiris mated with his second sister, Nephthys. One can see from this how the symbolism is developed: already in his mother’s womb, before his extra-uterine existence, Osiris commits incest; and in death, the second intra-uterine existence, he again commits incest, both times with a sister, for in remote antiquity brother-and-sister marriages were not only tolerated, but were a mark of the aristocracy. Zarathustra likewise recommended consanguineous marriages.

[351] The wicked Set lured Osiris into the chest by a ruse, in other words the original evil in man wants to get back into the mother again, and the illicit, incestuous longing for the mother is the ruse supposedly invented by Set. It is significant that it is “evil” which lures Osiris into the chest; for, in the light of teleology, the motif of containment signifies the latent state that precedes regeneration. Thus evil, as though cognizant of its imperfection, strives to be made perfect through rebirth—“Part of that power which would / Ever work evil, but engenders good!”40 The ruse, too, is significant: man tries to sneak into rebirth by a subterfuge in order to become a child again. That is how it appears to the “rational” mind. An Egyptian hymn41 even charges Isis with having struck down the sun god Ra by treachery: it was because of her ill will towards her son that she banished and betrayed him. The hymn describes how Isis fashioned a poisonous snake and set it in his path, and how the snake wounded the sun-god with its bite. From this wound he never recovered, so that he finally had to retire on the back of the heavenly cow. But the cow was the cow-headed mother-goddess (pl. XXXb), just as Osiris was the bull Apis. The mother is accused as though she were the cause of his having to fly to her in order to be cured of the wound she herself had inflicted. But the real cause of the wound is the incest-taboo,42 which cuts a man off from the security of childhood and early youth, from all those unconscious, instinctive happenings that allow the child to live without responsibility as an appendage of his parents. There must be contained in this feeling many dim memories of the animal age, when there was as yet no “thou shalt” and “thou shalt not,” and everything just happened of itself. Even now a deep resentment seems to dwell in man’s breast against the brutal law that once separated him from instinctive surrender to his desires and from the beautiful harmony of animal nature. This separation manifested itself in the incest prohibition and its correlates (marriage laws, food-taboos, etc.). So long as the child is in that state of unconscious identity with the mother, he is still one with the animal psyche and is just as unconscious as it. The development of consciousness inevitably leads not only to separation from the mother, but to separation from the parents and the whole family circle and thus to a relative degree of detachment from the unconscious and the world of instinct. Yet the longing for this lost world continues and, when difficult adaptations are demanded, is forever tempting one to make evasions and retreats, to regress to the infantile past, which then starts throwing up the incestuous symbolism. If only this temptation were perfectly clear, it would be possible, with a great effort of will, to free oneself from it. But it is far from clear, because a new adaptation or orientation of vital importance can only be achieved in accordance with the instincts. Lacking this, nothing durable results, only a convulsively willed, artificial product which proves in the long run to be incapable of life. No man can change himself into anything from sheer reason; he can only change into what he potentially is. When such a change becomes necessary, the previous mode of adaptation, already in a state of decay, is unconsciously compensated by the archetype of another mode. If the conscious mind now succeeds in interpreting the constellated archetype in a meaningful and appropriate manner, then a viable transformation can take place. Thus the most important relationship of childhood, the relation to the mother, will be compensated by the mother archetype as soon as detachment from the childhood state is indicated. One such successful interpretation has been, for instance, Mother Church (cf. pl. XXXa), but once this form begins to show signs of age and decay a new interpretation becomes inevitable.

[352] Even if a change does occur, the old form loses none of its attractions; for whoever sunders himself from the mother longs to get back to the mother. This longing can easily turn into a consuming passion which threatens all that has been won. The mother then appears on the one hand as the supreme goal, and on the other as the most frightful danger—the “Terrible Mother.”43

[353] After completing the night sea journey, the coffer containing Osiris was cast ashore at Byblos and came to rest in the branches of a cedar-tree, which shot up and enclosed the coffer in its trunk (cf. fig. 23). The king of the country, admiring the splendid tree, caused it to be cut down and made into a pillar supporting the roof of his house.44 This period of Osiris’ absence (the winter solstice) coincides with the age-old lament for the dead god, and his εὒρεσις (finding) was celebrated as a feast of joy.

[354] Later on Set dismembered the body and scattered the pieces. We find this motif of dismemberment in numerous sun-myths45 as a contrast to the putting together of the child in the mother’s womb. Actually Isis collected the pieces together again with the help of the jackal-headed Anubis. Here the dogs and jackals, devourers of corpses by night, assist in the reconstitution or reproduction of Osiris.46 To this necrophagous function the Egyptian vulture probably owes its symbolic mother significance. In ancient times the Persians used to throw out their corpses for the dogs to devour, just as, today in Tibet, the dead are left to the vultures,46a and in Bombay, where the Parsis expose their corpses on the “towers of silence.” The Persians had the custom of leading a dog to the bedside of a dying man, who then had to give the dog a morsel to eat.47 This custom suggests that the morsel should belong to the dog, so that he will spare the body of the dying man, just as Cerberus was pacified with the honey-cakes which Heracles gave him on his journey to hell. But when we consider the jackal-headed Anubis (pl. XXXIIa) who rendered such good service in gathering together the remains of Osiris, and the mother significance of the vulture, the question arises whether this ceremony may not have a deeper meaning. This problem has been taken up by Creuzer,48 who comes to the conclusion that the deeper meaning is connected with the astral form of the dog ceremony, i.e., the appearance of the dog-star at the highest point of the solstice. Hence the bringing in of the dog would have a compensatory significance, death being made equal to the sun at its highest point. This is a thoroughly psychological interpretation, as can be seen from the fact that death is quite commonly regarded as an entry into the mother’s womb (for rebirth). The interpretation would seem to be supported by the otherwise enigmatic function of the dog in the Mithraic sacrifice. In the monuments a dog is often shown leaping upon the bull killed by Mithras. In the light of the Persian legend, and on the evidence of the monuments themselves, this sacrifice should be conceived as the moment of supreme fruitfulness. This is most beautifully portrayed in the Mithraic relief at Heddernheim (pl. XXXIII). On one side of a large (formerly rotating) stone slab there is a stereotyped representation of the overthrow and sacrifice of the bull, while on the other side stand Sol with a bunch of grapes in his hand, Mithras with the cornucopia, and the dadophors bearing fruits, in accordance with the legend that from the dead bull comes all fruitfulness: fruits from his horns, wine from his blood, corn from his tail, cattle from his semen, garlic from his nostrils, and so forth. Over this scene stands Sylvanus, the beasts of the forest leaping away from him.

Fig. 23. Osiris in the cedar-coffin

Relief, Dendera, Egypt

[355] In this context the dog might very well have the significance suspected by Creuzer. Moreover the goddess of the underworld, Hecate, is dog-headed, like Anubis. As Canicula, she received dog sacrifices to keep away the pest. Her close relation to the moon-goddess suggests that she was a promoter of growth. Hecate was the first to bring Demeter news of her stolen daughter, another reminder of Anubis. Dog sacrifices were also offered to Eileithyia, the goddess of birth, and Hecate herself (cf. pl. LVIII) is, on occasion, a goddess of marriage and birth. The dog is also the regular companion of Aesculapius, the god of healing, who, while still a mortal, raised a man from the dead and was struck by a thunderbolt as a punishment. These associations help to explain the following passage in Petronius:

I earnestly beseech you to paint a small dog round the foot of my statue … so that by your kindness I may attain to life after death.49

[356] But to return to the myth of Osiris: although Isis had managed to collect the pieces of the body, its resuscitation was only partially successful because the phallus could not be found; it had been eaten by the fishes, and the reconstituted body lacked vital force.50 The phantom Osiris lay once more with Isis, but the fruit of their union was Harpocrates, who was weak “in the lower limbs” (γυíoν), i.e., in the feet. In the above-mentioned hymn, Ra was wounded in the foot by the serpent of Isis. The foot, as the organ nearest the earth, represents in dreams the relation to earthly reality and often has a generative or phallic significance.51 The name Oedipus, ‘Swell-foot,’ is suspicious in this respect. Osiris, although only a phantom, now makes the young sun (his son Horus) ready for battle with Set, the evil spirit of darkness. Osiris and Horus represent the father-son symbolism mentioned at the beginning. Osiris is thus flanked by the comely Horus and the misshapen Harpocrates, who is mostly shown as a cripple, sometimes distorted to the point of freakishness. It is just possible that the motif of the unequal brothers has something to do with the primitive conception that the placenta is the twin-brother of the new-born child.

[357] Osiris is frequently confused in tradition with Horus. The latter’s real name is Horpi-chrud,52 which is composed of chrud (child), and Hor (from hri, ‘up, above, on top’). The name thus signifies the “up-and-coming child,” the rising sun, as opposed to Osiris, who personifies the setting sun, the sun “in the Western Land.” So Osiris and Horpi-chrud are one being, both husband and son of the same mother. Khnum-Ra, the sun-god of Lower Egypt, is a ram, and his consort, the female divinity of the nome, is Hatmehit, who wears the fish on her head. She is the mother and spouse of Bi-neb-did (‘ram,’ the local name for Khnum-Ra). In the hymn of Hibis, Amon-Ra is invoked as follows:

Thy Ram dwelleth in Mendes, united as the fourfold god Thmuis. He is the phallus, lord of the gods. The bull of his mother rejoiceth in the cow, and the husband maketh fruitful through his seed.53

[358] In other inscriptions54 Hatmehit is called the “mother of Mendes.” (Mendes is the Greek form of Bi-neb-did.) She is also invoked as “The Good,” with the subsidiary meaning of tanofert, “young woman.” The cow as a mother-symbol (cf. pl. La) appears in all the innumerable forms and variations of Hathor-Isis (cf. pl. XXXb), and also in the feminine aspect of Nun (whose parallel is the primitive goddess Nit or Neith), the primary substance—moisture—which is both masculine and feminine by nature. Nun is therefore invoked55 as “Amon, the primordial waters,56 which was in the beginning.” He is also called the father of fathers, the mother of mothers. The corresponding invocation to Nun-Amon’s feminine aspect, Nit or Neith, says:

Nit, the Ancient, the Mother of God, Mistress of Esne, Father of Fathers, Mother of Mothers, who is the Scarab and the Vulture, who was in the beginning.

Nit, the Ancient, the mother who bore Ra, the God of Light, who, brought forth when there was nothing which brought forth.

The Cow, the Ancient, who bore the sun and set the seeds of gods and men.57 [Cf. figs. 24, 25.]

Fig. 24. Nut giving birth to the Sun

Relief, Egypt

[359] The word nun means ‘young, fresh, new,’ and also the new flood-waters of the Nile. In a metaphorical sense it is used for the chaotic waters of the beginning, and for the birth-giving primary substance,58 which is personified as the goddess Naunet. From her sprang Nut, the sky-goddess, who is represented with a starry body or as a heavenly cow dotted with stars (figs. 24, 25).

[360] So when the sun-god Ra retires on the back of the heavenly cow, it means that he is going back into the mother in order to rise again as Horus. In the morning the goddess is the mother, at noon she is the sister-wife, and at evening once more the mother who takes back the dead into her womb.

Fig. 25. The Divine Cow

From the tomb of Seti I, Egypt

[361] Thus the fate of Osiris is explained: he enters into the mother’s womb, into the coffer, the sea, the tree, the Astarte column; is dismembered, put together again, and reappears in his son Horpi-chrud.

[362] Before we enter upon the other mysteries which this myth has in store for us, it will be as well to say a few words more about the symbol of the tree. Osiris comes to rest in the branches of a tree, which grow up round him.59 The motif of embracing and entwining is often found in the sun myths and rebirth myths, as in the story of Sleeping Beauty, or the legend of the girl who was imprisoned between the bark and the wood of a tree.60 A primitive myth tells of a sun-hero who has to be freed from a creeping plant.61 The girl dreams that her lover has fallen into the water; she tries to rescue him, but first has to pull seaweed out of the water, then she catches him. In an African myth the hero, after his deed, has to be disentangled from the seaweed. In a Polynesian story the hero’s canoe is caught in the tentacles of a giant polyp, just as Ra’s barge was entwined by the nocturnal serpent on the night sea journey. The motif of entwining also occurs in Sir Edwin Arnold’s poetic version of the story of Buddha’s birth:

Queen Maya stood at noon, her days fulfilled,

Under a palsa in the palace-grounds,

A stately trunk, straight as a temple-shaft,

With crown of glossy leaves and fragrant blooms;

And, knowing the time come—for all things knew—

The conscious tree bent down its boughs to make

A bower about Queen Maya’s majesty:

And Earth put forth a thousand sudden flowers

To spread a couch; while, ready for the bath,

The rock hard by gave out a limpid stream

Of crystal flow. So brought she forth her child.62

[363] There is a very similar motif in the cult-legend of the Samian Hera. Every year her image “disappeared” from the temple, attached itself to a lygos-tree somewhere on the seashore, and was entwined in its branches. There it was “found” and regaled with wedding-cakes. This festival was undoubtedly a hieros gamos, for in Samos there was a legend that Zeus had previously had a long-drawn-out clandestine love-affair with Hera. In Plataea and Argos a wedding procession was staged in their honour with bridesmaids, wedding feast, etc. The festival took place in the “wedding month” of Gamelion (beginning of February). The image was carried to a lonely spot in the woods, which is in keeping with Plutarch’s story that Zeus kidnapped Hera and hid her in a cave on Mount Cithaeron. After our previous remarks we have to conclude that there is still another train of thought connected with the hieros gamos, namely, rejuvenation magic. The disappearance and hiding of the image in the wood, in the cave, on the seashore, its twining-about by the lygos-tree,63 all this points to death and rebirth. The early springtime, Gamelion, fits in very well with this theory. In fact, Pausanias64 tells us that the Argive Hera became a virgin again by taking a yearly dip in the fountain of Kanathos. The significance of this bath is further increased by the report that, in the Plataean cult of Hera Teleia, Tritonian nymphs appeared as water-carriers. The Iliad describes Zeus’ conjugal couch on Mount Ida as follows:

As he spoke, the Son of Cronos took his wife in his arms; and the gracious earth sent up fresh grass beneath them, dewy lotus and crocuses, and a soft and crowded bed of hyacinths, to lift them off the ground. In this they lay, covered by a beautiful golden cloud, from which a rain of glistening dewdrops fell.… The Father lay peacefully on top of Gargarus with his arms round his wife, conquered by sleep and love.…65

[364] Drexler sees in this description66 an allusion to the garden of the gods on the extreme Western shore of the ocean—an idea which might have been taken from a pre-Homeric hieros gamos hymn.67 The Western Land is the land of the setting sun; Heracles and Gilgamesh hasten thither, where the sun and the maternal sea are united in an eternally rejuvenating embrace. This seems to confirm our conjecture that the hieros gamos is connected with a rebirth myth. Pausanias mentions a related myth-fragment which says that the image of Artemis Orthia was also called Lygodesma, ‘willow-captive,’68 because it was found in a willow-tree. There seems to be some connection here with the popular Greek festival of the hieros gamos and its above-mentioned customs.

[365] The motif of “devouring” (pls. XXXIIb, XXXIV), which Frobenius has shown to be one of the commonest components of the sun myth, is closely connected with embracing and entwining. The “whale-dragon” always “devours” the hero, but the devouring can also be partial. For instance, a six-year-old girl who hated going to school once dreamt that her leg was encircled by a large red worm. Contrary to what might be expected, she evinced a tender interest in the creature. Again, an adult patient who was unable to separate from an older woman friend on account of a strong mother transference to her, dreamt that she had to cross a broad stream. There was no bridge, but she found a place where she could step across. Just as she was about to do so, a large crab that lay hidden in the water seized hold of her foot and would not let go.69

[366] This picture is borne out by etymology. There is an Indo-European root *υélu-, with the meaning of ‘encircling, enveloping, winding, turning.’ From this are derived: Skr. val, valati, ‘to cover, envelop, surround, encircle’; valli, ‘creeping plant’; ulūta, ‘boa-constrictor’ = Lat. volutus; Lith. velù, velti = G. wickeln, ‘to wind, wrap’; Church Slav, vlina = OHG. wella, ‘a wave.’ A related root is vlvo, ‘covering, coil, membrane, womb.’ Skr. ulva, ulba, has the same meaning; Lat. volva, volvula, vulva. Vélu is also cognate with ulvora, ‘fruitful field, sheath or husk of a plant.’ Skr. urvárā, ‘sown field’; Zend urvara, ‘plant.’ The same root vel also has the meaning of G. wallen, ‘boil, undulate.’ Skr. ulmuka, ‘conflagration’; Gr. Faλέa, Fέλa, Goth. vulan = wallen. OHG. and MHG. walm = ‘warmth.’70 (It is typical that in the state of “involution” the hero’s hair always falls out with the heat.) Vel is also found with the meaning ‘to sound,’71 and ‘to will, wish.’

[367] The motif of entwining is a mother-symbol.72 The entwining trees are at the same time birth-giving mothers (cf. pl. XXXIX), as in the Greek myth where the  are ash-trees, the mothers of the men of the Bronze Age. The Bundahish symbolizes the first human beings, Mashya and Mashyoi, as the tree Rivas. According to a Nordic myth, God created man by breathing life into a substance called tre73 (tree, wood).74 Gr.

are ash-trees, the mothers of the men of the Bronze Age. The Bundahish symbolizes the first human beings, Mashya and Mashyoi, as the tree Rivas. According to a Nordic myth, God created man by breathing life into a substance called tre73 (tree, wood).74 Gr.  also means ‘wood.’ In the wood of the world-ash Yggdrasill a human pair hide themselves at the end of the world, and from them will spring a new race of men.75 At the moment of universal destruction the world-ash becomes the guardian mother, the tree pregnant with death and life.76 The regenerative function of the world-ash helps to explain the image in the chapter of the Egyptian Book of the Dead called “The Gate of Knowledge of the Souls of the East”:

also means ‘wood.’ In the wood of the world-ash Yggdrasill a human pair hide themselves at the end of the world, and from them will spring a new race of men.75 At the moment of universal destruction the world-ash becomes the guardian mother, the tree pregnant with death and life.76 The regenerative function of the world-ash helps to explain the image in the chapter of the Egyptian Book of the Dead called “The Gate of Knowledge of the Souls of the East”:

I am the pilot in the holy keel, I am the steersman who allows himself no rest in the ship of Ra.77 I know the tree of emerald green from whose midst Ra rises to the height of the clouds.78

[368] Ship and tree (i.e., the ship of death and tree of death) are closely related here. (P1. XXXV.) The idea is that Ra rises up, born from the tree. The representations of the sun-god Mithras should probably be interpreted in the same way. In the Heddernheim Relief (pl. XL) he is shown with half his body rising from the top of a tree, and in other monuments half his body is stuck in the rock, which clearly points to the rock-birth. Often there is a stream near his birthplace. This conglomeration of symbols79 is also found in the birth of Aschanes, the first Saxon king, who grew from the Harz rocks in the middle of a wood near a fountain.80 Here all the mother symbols are united—earth, wood, and water. So it is only logical that in the Middle Ages the tree was poetically addressed with the honorific title of “Lady.” Nor is it surprising that Christian legend transformed the tree of death, the Cross, into the Tree of Life, so that Christ is often shown hanging on a green tree among the fruit (pl. XXXVI). The derivation of the Cross from the Tree of Life, which was an authentic religious symbol even in Babylonian times, is considered entirely probable by Zöckler,81 an authority on the history of the Cross. The pre-Christian meaning of so universal a symbol does not contradict this view; quite the contrary, for its meaning is life. Nor does the existence of the cross in the sun-cult (where the regular cross and the swastika represent the sun-wheel) and in the cult of the love-goddesses in any way contradict its historical significance. Christian legend has made abundant use of this symbolism. The student of medieval art will be familiar with the representation of the Cross growing from Adam’s grave (pl. XXXVII). The legend says that Adam was buried on Golgotha, and that Seth planted on his grave a twig from the tree of Paradise, which grew into Christ’s Cross, the Tree of Death.82 As we know, it was through Adam’s guilt that sin and death came into the world, and Christ through his death redeemed us from the guilt. If we ask, In what did Adam’s guilt consist? the answer is that the unpardonable sin to be punished by death was that he dared to eat of the tree of Paradise.83 The consequences of this are described in a Jewish legend: one who was permitted to gaze into Paradise after the Fall saw the tree and the four streams, but the tree was withered, and in its branches lay a babe. The “mother” had become pregnant.84