Wuthering Heights as a Classic

This essay also comes from the Eliot lecture series given at the University of Kent at Canterbury in 1973, published in 1975. I see on returning to this discourse that it will not be easy to read for anybody who hasn’t read Wuthering Heights pretty recently. I wrote it at a time when I was interested in ways of talking about narrative that were newly imported from Paris and, in the case of Wolfgang Iser, from Germany. If I were writing now I should not be tackling the issues in quite this way, but I think I was on the right lines and wonder still whether there was any other way to take on the job; which means, I suppose, that I couldn’t, now, even pretend to do so.

I have chosen Wuthering Heights for what I take to be good reasons. It meets the requirement that it is read in a generation far separated from the one it was presented to; and it has other less obvious advantages. It happens that I had not read the novel for many years; furthermore, although I could not be unaware that it had suffered a good deal of interpretation, and had been the centre of quarrels, I had also omitted to read any of this secondary material. These chances put me in a position unfamiliar to the teacher of literature; I could consider my own response to a classic more or less untrammelled by too frequent reading, and by knowledge of what it had proved possible, or become customary, to say about it. This strikes me as a happy situation, though some may call it shameful. Anyway, it is the best way I can think of to arrive at some general conclusions about the classic, though I daresay those conclusions will sound more like a programme for research than a true ending to this briefer exercise.

I begin, then, with a partial reading of Wuthering Heights which

represents a straightforward encounter between a competent modern reader (the notion of competence is, I think, essential, however much you may think this demonstration falls short of it) and a classic text. However, in assuming this role, I could not avoid noticing some remarks that are not in the novel at all, but in Charlotte Brontë’s Biographical Notice of her sisters, in which she singles out a contemporary critic as the only one who got her sister’s book right. ‘Too often,’ she says, ‘do reviewers remind us of the mob of Astrologers, Chaldeans and Soothsayers gathered before the “writing on the wall”, and unable to read the characters or make known the interpretation.’ One, however, has accurately read ‘the Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin of an original mind’ and ‘can say with confidence, “This is the interpretation thereof”’. This latterday Daniel was Sidney Dobell, but a modern reader who looks him up in the hope of coming upon what would after all be a very valuable piece of information is likely to be disappointed. Very few would dream of doing so; most would mistrust the critic for whom such claims were made, or the book which lent itself to them. Few would believe that such an interpretation exists, however frequently the critics produce new ‘keys’. For we don’t think of the novel as a code, or a nut, that can be broken; which contains or refers to a meaning all will agree upon if it can once be presented en clair. We need little persuasion to believe that a good novel is not a message at all. We assume in principle the rightness of the plurality of interpretations to which I now, in ignorance of all the others, but reasonably confident that I won’t repeat them, now contribute.

When Lockwood first visits Wuthering Heights he notices, among otherwise irrelevant decorations carved above the door, the date 1500 and the name Hareton Earnshaw. It is quite clear that everybody read and reads this (on p. 2) as a sort of promise of something else to come. It is part of what is nowadays called a ‘hermeneutic code’; something that promises, and perhaps after some delay provides, explanation. There is, of course, likely to be some measure of peripeteia or trick; you would be surprised if the explanation were not, in some way, surprising, or at any rate, at this stage unpredictable. And so it proves. The expectations aroused by these inscriptions are strictly generic; you must know things of this kind before you can entertain expectations of the sort I mention. Genre in this sense is what Leonard Meyer

(writing of music) calls ‘an internalized probability system’.1 Such a system could, but perhaps shouldn’t, be thought of as constituting some sort of contract between reader and writer. Either way, the inscriptions can be seen as something other than simple elements in a series of one damned thing after another, or even of events relative to a story as such. They reduce the range of probabilities, reduce randomness, and are expected to recur. There will be ‘feedback’. This may not extinguish all the informational possibilities in the original stimulus, which may be, and in this case is, obscurer than we thought, ‘higher’, as the information theorists say, ‘in entropy’. The narrative is more than merely a lengthy delay, after which a true descendant of Hareton Earnshaw reoccupies the ancestral house; though there is little delay before we hear about him, and can make a guess if we want.

When Hareton is first discussed, Nelly Dean rather oddly describes him as ‘the late Mrs Linton’s nephew’. Why not ‘the late Mr Earnshaw’s son’? It is only in the previous sentence that we have first heard the name Linton, when the family of that name is mentioned as having previously occupied Thrushcross Grange. Perhaps we are to wonder how Mrs Linton came to have a nephew named Earnshaw. At any rate, Nelly’s obliquity thus serves to associate Hareton, in a hazy way, with the house on which his name is not carved, and with a family no longer in evidence. Only later do we discover that he is in the direct Earnshaw line, in fact, as Nelly says, ‘the last of them’. So begins the provision of information which both fulfils and qualifies the early ‘hermeneutic’ promise; because, of course, Hareton, his inheritance restored, goes to live at the Grange. The two principal characters remaining at the end are Mr and Mrs Hareton Earnshaw. The other names, which have intruded on Earnshaw – Linton and Heathcliff – are extinct. In between there have been significant recursions to the original inscription – in Chapter XX Hareton cannot read it; in XXIV he can read the name but not the date.

We could say, I suppose, that this so far tells us nothing about Wuthering Heights that couldn’t, with appropriate changes, be said of most novels. All of them contain the equivalent of such inscriptions; indeed all writing is a sort of inscription, cut memorably into the uncaused flux of event; and inscriptions of the kind I am talking about are interesting secondary clues about the nature of the writing in which

they occur. They draw attention to the literariness of what we are reading, indicate that the story is a story, perhaps with beneficial effects on our normal powers of perception; above all they distinguish a literary system which has no constant relation to readers with interests and expectations altered by long passages of time. Or, to put it another way, Emily Brontë’s contemporaries operated different probability systems from ours, and might well ignore whatever in a text did not comply with their generic expectations, dismissing the rest somehow - by skipping, by accusations of bad craftsmanship, inexperience, or the like. In short, their internalized probability systems survive them in altered and less stringent forms; we can read more of the text than they could, and of course read it differently. In fact, the only works we value enough to call classic are those which, as they demonstrate by surviving, are complex and indeterminate enough to allow us our necessary pluralities. That ‘Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin’ has now many interpretations. It is in the nature of works of art to be open, in so far as they are ‘good’; though it is in the nature of authors, and of readers, to close them.

The openness of Wuthering Heights might be somewhat more extensively illustrated by an inquiry into the passage describing Lockwood’s bad night at the house, when, on his second visit, he was cut off from Thrushcross Grange by a storm. He is given an odd sort of bed in a bedroom-within-a-bedroom; Catherine Earnshaw slept in it and later Heathcliff would die in it. Both the bed and the lattice are subjects of very elaborate ‘play’; but I want rather to consider the inscriptions Lockwood examines before retiring. There is writing on the wall, or on the ledge by his bed: it ‘was nothing but a name repeated in all kinds of characters, large and small – Catherine Earnshaw, here and there varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and then again to Catherine Linton’. When he closes his eyes Lockwood is assailed by white letters ‘which started from the dark, as vivid as spectres – the air swarmed with Catherines’. He has no idea whatever to whom these names belong, yet the expression ‘nothing but a name’ seems to suggest that they all belong to one person. Waking from a doze he finds the name Catherine Earnshaw inscribed in a book his candle has scorched.

It is true that Lockwood has earlier met a Mrs Heathcliff, and got into a tangle about who she was, taking first Heathcliff and then

Hareton Earnshaw for her husband, as indeed, we discover she, in a different sense, had also done or was to do. For she had a merely apparent kinship relation with Heathcliff – bearing his name as the wife of his impotent son and having to tolerate his ironic claim to fatherhood – as a prelude to the restoration of her true name, Earnshaw; it is her mother’s story reversed. But Lockwood was not told her first name. Soon he is to encounter a ghost called Catherine Linton; but if the scribbled names signify one person he and we are obviously going to have to wait to find out who it is. Soon we learn that Mrs Heathcliff is Heathcliff’s daughter-in-law, née Catherine Linton, and obviously not the ghost. Later it becomes evident that the scratcher must have been Catherine Earnshaw, later Linton, a girl long dead who might well have been Catherine Heathcliff, but wasn’t.

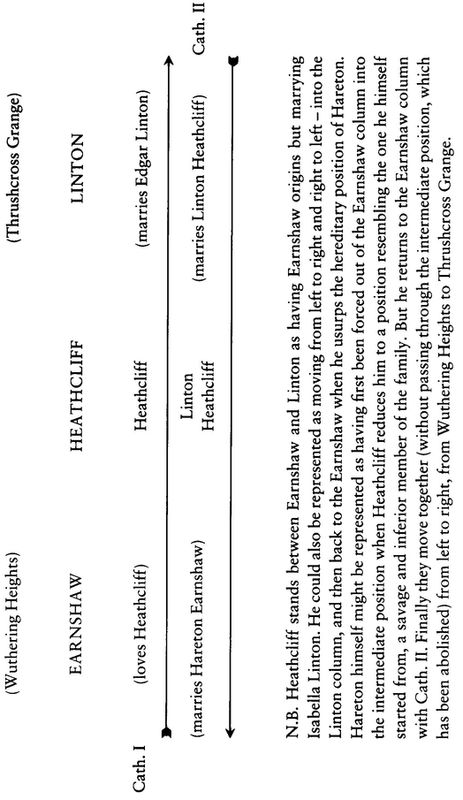

When you have processed all the information you have been waiting for you see the point of the order of the scribbled names, as Lockwood gives them: Catherine Earnshaw, Catherine Heathcliff, Catherine Linton. Read from left to right they recapitulate Catherine Earnshaw’s story; read from right to left, the story of her daughter, Catherine Linton. The names Catherine and Earnshaw begin and end the narrative. Of course some of the events needed to complete this pattern had not occurred when Lockwood slept in the little bedroom; indeed the marriage of Hareton and Catherine is still in the future when the novel ends. Still, this is an account of the movement of the book: away from Earnshaw and back, like the movement of the house itself. And all the movement must be through Heathcliff.

Charlotte Bronte remarks, from her own experience, that the writer says more than he knows, and was emphatic that this was so with Emily. ‘Having formed these beings, she did not know what she had done.’ Of course this strikes us as no more than common sense; though Charlotte chooses to attribute it to Emily’s ignorance of the world. A narrative is not a transcription of something pre-existent. And this is precisely the situation represented by Lockwood’s play with the names he does not understand, his constituting, out of many scribbles, a rebus for the plot of the novel he’s in. The situation indicates the kind of work we must do when a narrative opens itself to us, and contains information in excess of what generic probability requires.

Consider the names again; of course they reflect the isolation of the

society under consideration, but still it is remarkable that in a story whose principal characters all marry there are effectively only three surnames, all of which each Catherine assumes. Furthermore, the Earnshaw family makes do with only three Christian names, Catherine, Hindley, Hareton. Heathcliff is a family name also, but parsimoniously, serving as both Christian name and surname; always lacking one or the other, he wears his name as an indication of his difference, and this persists after death since his tombstone is inscribed with the one word Heathcliff. Like Frances, briefly the wife of Hindley, he is simply a sort of interruption in the Earnshaw system.

Heathcliff is then as it were between names, as between families (he is the door through which Earnshaw passes into Linton, and out again to Earnshaw). He is often introduced, as if characteristically, standing outside, or entering, or leaving, a door. He is in and out of the Earnshaw family simultaneously; servant and child of the family (like Hareton, whom he puts in the same position, he helps to indicate the archaic nature of the house’s society, the lack of sharp social division, which is not characteristic of the Grange). His origins are equally betwixt and between: the gutter or the royal origin imagined for him by Nelly; prince or pauper, American or Lascar, child of God or devil. This betweenness persists, I think: Heathcliff, for instance, fluctuates between poverty and riches; also between virility and impotence. To Catherine he is between brother and lover; he slept with her as a child, and again in death, but not between latency and extinction. He has much force, yet fathers an exceptionally puny child. Domestic yet savage like the dogs, bleak yet full of fire like the house, he bestrides the great opposites: love and death (the necrophiliac confession), culture and nature (‘half-civilized ferocity’) in a posture that certainly cannot be explained by any generic formula (‘Byronic’ or ‘Gothic’).

He stands also between a past and a future; when his force expires the old Earnshaw family moves into the future associated with the civilized Grange, where the insane authoritarianism of the Heights is a thing of the past, where there are cultivated distinctions between gentle and simple – a new world in the more civil south. It was the Grange that first separated Heathcliff from Catherine, so that Earnshaws might eventually live there. Of the children – Hareton, Cathy, and Linton – none physically resembles Heathcliff; the first two

have Catherine’s eyes (XXXIII) and the other is, as his first name implies, a Linton. Cathy’s two cousin-marriages – constituting an endogamous route to the civilized exogamy of the south – are the consequence of Heathcliff’s standing between Earnshaw and Linton, north and south; earlier he had involuntarily saved the life of the baby Hareton. His ghost and Catherine’s, at the end, are of interest only to the superstitious, the indigenous now to be dispossessed by a more rational culture.

If we look, once more, at Lockwood’s inscriptions, we may read them thus (see facing page).

Earnshaws persist, but they must eventually do so within the Linton culture. Catherine burns up in her transit from left to right. The quasi-Earnshaw union of Heathcliff and Isabella leaves the younger Cathy an easier passage; she has only to get through Linton Heathcliff, who is replaced by Hareton Earnshaw; Hareton has suffered part of Heathcliff’s fate, moved, as it were, from Earnshaw to Heathcliff, and replaced him as son-servant, as gratuitously cruel; but he is the last of the Earnshaws, and Cathy can both restore to him the house on which his name is carved, and take him on the now smooth path to Thrushcross Grange.

Novels, even this one, were read in houses more like the Grange than the Heights, as the emphasis on the ferocious piety of the Earnshaw library suggests. The order of the novel is a civilized order; it presupposes a reader in the midst of an educated family and habituated to novel reading; a reader, moreover, who believes in the possibility of effective ethical choices. And because this is the case, the author can allow herself to meet his proper expectations without imposing on the text or on him absolute generic control. She need not, that is, know all that she is saying. She can, in all manner of ways, invite the reader to collaborate, leave to him the supply of meaning where the text is indeterminate or discontinuous, where explanations are required to fill narrative lacunae.

Instances of this are provided by some of the dreams in the book.2 Lockwood’s brief dream of the spectral letters is followed by another about an interminable sermon, which develops from hints about Joseph in Catherine’s Bible. The purport of this dream is obscure. The preacher Jabes Branderham takes a hint from his text and expands the seven deadly sins into seventy times seven plus one. It is when he reaches the last section that Lockwood’s patience runs out, and he protests, with his own allusion to the Bible: ‘He shall return no more to his house, neither shall his place know him any more.’ Dreams in stories are usually given a measure of oneiric ambiguity, but stay fairly close to the narrative line, or if not, convey information otherwise useful; but this one does not appear to do so, except in so far as that text may bear obscurely and incorrectly on the question of where Hareton will end up. It is, however, given a naturalistic explanation: the rapping of the preacher on the pulpit is a dream version of the rapping of the fir tree on the window.

Lockwood once more falls asleep, but dreams again, and ‘if possible, still more disagreeably than before’. Once more he hears the fir-bough, and rises to silence it; he breaks the window and finds himself clutching the cold hand of a child who calls herself Catherine Linton.

He speaks of this as a dream, indeed he ascribes to it ‘the intense horror of nightmare’, and the blood that runs down into the bedclothes may be explained by his having cut his hand as he broke the glass; but he does not say so, attributing it to his own cruelty in rubbing the child’s wrist on the pane; and Heathcliff immediately makes it obvious that of the two choices the text has so far allowed us the more acceptable is that Lockwood was not dreaming at all.

So we cannot dismiss this dream as ‘Gothic’ ornament or commentary, or even as the kind of dream Lockwood has just had, in which the same fir-bough produced a comically extended dream-explanation of its presence. There remain all manner of puzzles: why is the visitant a child and, if a child, why Catherine Linton? The explanation, that this name got into Lockwood’s dream from a scribble in the Bible, is one even he finds hard to accept. He hovers between an explanation involving ‘ghosts and goblins’, and the simpler one of nightmare; though he has no more doubt than Heathcliff that ‘it’ – the child – was trying to enter. For good measure he is greeted, on going downstairs, by a cat, a brindled cat, with its echo of Shakespearian witchcraft.

It seems plain, then, that the dream is not simply a transformation of the narrative, a commentary on another level, but an integral part of it. The Branderham dream is, in a sense, a trick, suggesting a measure of rationality in the earlier dream which we might want to transfer

to the later experience, as Lockwood partly does. When we see that there is a considerable conflict in the clues as to how we should read the second tapping and relate it to the first we grow aware of further contrasts between the two, for the first is a comic treatment of 491 specific and resistible sins for which Lockwood is about to be punished by exile from his home, and the second is a more horrible spectral invasion of the womb-like or tomb-like room in which he is housed. There are doubtless many other observations to be made; it is not a question of deciding which is the single right reading, but of dealing, as reader, with a series of indeterminacies which the text will not resolve.

Nelly Dean refuses to listen to Catherine’s dream, one of those which went through and through her ‘like wine through water’; and of those dreams we hear nothing save this account of their power. ‘We’re dismal enough without conjuring up ghosts and visions to perplex us,’ says Nelly – another speaking silence in the text, for it is implied that we are here denied relevant information. But she herself suffers a dream or vision. After Heathcliff’s return she finds herself at the signpost: engraved in its sandstone – with all the permanence that Hareton’s name has on the house – are ‘Wuthering Heights’ to the north, ‘Gimmerton’ to the east, and ‘Thrushcross Grange’ to the south. Soft south, harsh north, and the rough civility of the market town (something like that of Nelly herself) in between. As before, these inscriptions provoke a dream apparition, a vision of Hindley as a child. Fearing that he has come to harm, she rushes to the Heights and again sees the spectral child, but it turns out to be Hareton, Hindley’s son. His appearance betwixt and between the Heights and the Grange was proleptic; now he is back at the Heights, a stone in his hand, threatening his old nurse, rejecting the Grange. And as Hindley turned into Hareton, so Hareton turns into Heathcliff, for the figure that appears in the doorway is Heathcliff.

This is very like a real dream in its transformations and displacements. It has no simple narrative function whatever, and an abridgement might leave it out. But the confusion of generations, and the double usurpation of Hindley by his son and Heathcliff, all three of them variants of the incivility of the Heights, gives a new relation to the agents, and qualifies our sense of all narrative explanations offered

in the text. For it is worth remarking that no naturalistic explanation of Nelly’s experience is offered; in this it is unlike the treatment of the later vision, when the little boy sees the ghost of Heathcliff and ‘a woman’, a passage which is a preparation for further ambiguities in the ending. Dreams, visions, ghosts – the whole pneumatology of the book is only indeterminately related to the ‘natural’ narrative. And this serves to muddle routine ‘single’ readings, to confound explanation and expectation, and to make necessary a full recognition of the intrinsic plurality of the text.

Would it be reasonable to say this: that the mingling of generic opposites – daylight and dream narratives – creates a need, which we must supply, for something that will mediate between them? If so, we can go on to argue that the text in our response to it is a provision of such mediators, between life and death, the barbaric and the civilized, family and sexual relations. The principal instrument of mediation may well be Heathcliff: neither inside nor out, neither wholly master nor wholly servant, the husband who is no husband, the brother who is no brother, the father who abuses his changeling child, the cousin without kin. And that the chain of narrators serves to mediate between the barbarism of the story and the civility of the reader – making the text itself an intermediate term between archaic and modern – must surely have been pointed out.

What we must not forget, however, is that it is in the completion of the text by the reader that these adjustments are made; and each reader will make them differently. Plurality is here not a prescription but a fact. There is so much that is blurred and tentative, incapable of decisive explanation; however we set about our reading, with a sociological or a pneumatological, a cultural or a narrative code uppermost in our minds, we must fall into division and discrepancy; the doors of communication are sometimes locked, sometimes open, and Heathcliff may be astride the threshold, opening, closing, breaking. And it is surely evident that the possibilities of interpretation increase as time goes on. The constraints of a period culture dissolve, generic presumptions which concealed gaps disappear, and we now see that the book, as James thought novels should, truly ‘glories in a gap’, a hermeneutic gap in which the reader’s imagination must operate, so that he speaks continuously in the text. For these reasons the rebus – Catherine

Earnshaw, Catherine Heathcliff, Catherine Linton – has exemplary significance. It is a riddle that the text answers only silently; for example it will neither urge nor forbid you to remember that it resembles the riddle of the Sphinx – what manner of person exists in these three forms? – to which the single acceptable and probable answer involves incest and ruin.

I have not found it possible to speak of Wuthering Heights in this light without, from time to time, hinting – in a word here, or a trick of procedure there – at the new French criticism. I am glad to acknowledge this affinity, but it also seems important to dissent from the opinion that such ‘classic’ texts as this – and the French will call them so, but with pejorative intent – are essentially naïve, and become in a measure plural only by accident. The number of choices is simply too large; it is impossible that even two competent readers should agree on an authorized naïve version. It is because texts are so naive that they can become classics. It is true, as I have said, that time opens them up; if readers were immortal the classic would be much closer to changelessness; their deaths do, in an important sense, liberate the texts. But to attribute the entire potential of plurality to that cause (or to the wisdom and cunning of later readers) is to fall into a mistake. The ‘Catherines’ of Lockwood’s inscriptions may not have been attended to, but there they were in the text, just as ambiguous and plural as they are now. What happens is that methods of repairing such indeterminacy change; and, as Wolfgang Iser’s neat formula has it, ‘the repair of indeterminacy’ is what gives rise ‘to the generation of meaning’.3

Having meditated thus on Wuthering Heights I passed to the second part of my enterprise and began to read what people have been saying about the book. I discovered without surprise that no two readers saw it exactly alike; some seemed foolish and some clever, but whether they were of the party that claims to elucidate Emily Brontë’s intention, or libertarians whose purpose is to astonish us, all were different. This secondary material is voluminous, but any hesitation I might have had about selecting from it was ended when I came upon an essay which in its mature authority dwarfs all the others: Q. D. Leavis’s ‘A Fresh Approach to Wuthering Heights’.4

Long-meditated, rich in insights, this work has a sober force that nothing I say could, or is intended to, diminish. Mrs Leavis remarks at the outset that merely to assert the classic status of such a book as Wuthering Heights is useless; that the task is not to be accomplished by ignoring ‘recalcitrant elements’ or providing sophistical explanations of them. One has to show ‘the nature of its success’; and this, she at once proposes, means giving up some parts of the text. ‘Of course, in general one attempts to achieve a reading of a text which includes all its elements, but here I believe we must be satisfied with being able to account for some of them and concentrate on what remains.’ And she decides that Emily Bronte through inexperience, and trying to do too much, leaves in the final version vestiges of earlier creations, ‘unregenerate writing’, which is discordant with the true ‘realistic novel’ we should attend to.

She speaks of an earlier version deriving from King Lear, with Heathcliff as an Edmund figure, and attributes to this layer some contrived and unconvincing scenes of cruelty. Another layer is the fairy story, Heathcliff as the prince transformed into a beast; another is the Romantic incest-story: Heathcliff as brother-lover; and nearer the surface, a sociological novel, of which she has no difficulty in providing, with material from the text, a skilful account. These vestiges explain some of the incongruities and inconsistencies of the novel – for example, the ambiguity of the Catherine – Heathcliff relationship – and have the effect of obscuring its ‘human centrality’. To summarize a long and substantial argument, this real novel, which we come upon clearly when the rest is cut away, is founded on the contrast between the two Catherines, the one willing her own destruction, the other educated by experience and avoiding the same fate. Not only does this cast a new light on such characters as Joseph and Nelly Dean as representatives of a culture that, as well as severity, inculcates a kind of natural piety, but enables us to see Emily Bronte as ‘a true novelist … whose material was real life and whose concern was to promote a fine awareness of human relations and the problem of maturity’. And we can’t see this unless we reject a good deal of the text as belonging more to ‘self-indulgent story’ than to the ‘responsible piece of work’ Emily was eventually able to perform. Heathcliff we are to regard as ‘merely a convenience’; in a striking comparison with Dostoevsky’s

Stavrogin, Mrs Leavis argues that he is ‘enigmatic … only by reason of his creator’s indecision’, and that to find reasons for thinking otherwise is ‘misguided critical industry’. By the same token the famous passages about Catherine’s love for Heathcliff are dismissed as rhetorical excesses, obstacles to the ‘real novel enacted so richly for us to grasp in all its complexity’.5

Now it seems very clear to me that the ‘real novel’ Mrs Leavis describes is there, in the text. It is also clear that she is aware of the danger in her own procedures, for she explains how easy it would be to account for Wuthering Heights as a sociological novel by discarding certain elements and concentrating on others, which, she says, would be ‘misconceiving the novel and slighting it’. What she will not admit is that there is a sense in which all these versions are not only present but have a claim on our attention. She creates a hierarchy of elements, and does so by a peculiar archaeology of her own, for there is no evidence that the novel existed in the earlier forms which are supposed to have left vestiges in the only text we have, and there is no reason why the kind of speculation and conjecture on which her historical argument depends could not be practised with equal right by proponents of quite other theories. Nor can I explain why it seemed to her that the only way to establish hers as the central reading of the book was to explain the rest away; for there, after all, the others are. Digging and carbon-dating simply have no equivalents here; there is no way of distinguishing old signs from new; among readings which attend to the text it cannot be argued that one attends to a truer text than all the others.

It is true that ‘a fine awareness of human relations’, and a certain maturity, may be postulated as classic characteristics; Eliot found them in Virgil. But it is also true that the coexistence in a single text of a plurality of significances from which, in the nature of human attentiveness, every reader misses some – and, in the nature of human individuality, prefers one – is, empirically, a requirement and a distinguishing feature of the survivor, centum qui perfecit annos. All those little critics, each with his piece to say about King Lear or Wuthering Heights, may be touched by a venal professional despair, but at least their numbers and their variety serve to testify to the plurality of the documents on which they swarm; and though they may lack authority,

sometimes perhaps even sense, many of them do point to what is there and ought not to be wished away.

A recognition of this plurality relieves us of the necessity of a Wuthering Heights without a Heathcliff, just as it does of a Wuthering Heights that ‘really’ ends with the death of Catherine, or for that matter an Aeneid which breaks off, as some of the moral allegorists would perhaps have liked it to, at the end of Book VI. A reading such as mine is of course extremely selective, but it has the negative virtue that it does not excommunicate from the text the material it does not employ; indeed, it assumes that it is one of the very large number of readings that may be generated from the text of the novel. They will of course overlap, as mine in some small measure does with that of Mrs Leavis.

And this brings me to the point: Mrs Leavis’s reading is privileged; what conforms with it is complex, what does not is confused; and presumably all others would be more or less wrong, in so far as they treated the rejected portions as proper objects of attention. On the other hand, the view I propose does not in any way require me to reject Mrs Leavis’s insights. It supposes that the reader’s share in the novel is not so much a matter of knowing, by heroic efforts of intelligence and divination, what Emily Brontë really meant – knowing it, quite in the manner of Schleiermacher, better than she did – as of responding creatively to indeterminacies of meaning inherent in the text and possibly enlarged by the action of time.

We are entering, as you see, a familiar zone of dispute. Mrs Leavis is rightly concerned with what is ‘timeless’ in the classic, but for her this involves the detection and rejection of what exists, it seems to her irrelevantly or even damagingly, in the aspect of time. She is left, in the end, with something that, in her view, has not changed between the first writing and her reading. I, on the other hand, claimed to be reading a text that might well signify differently to different generations, and different persons within those generations. It is a less attractive view, I see; an encouragement to foolishness, a stick that might be used, quite illicitly as it happens, to beat history, and sever our communications with the dead. But it happens that I set a high value on these, and wish to preserve them. I think there is a substance that prevails, however powerful the agents of change; that King Lear, underlying a thousand dispositions, subsists in change, prevails, by

being patient of interpretation; that my Wuthering Heights, sketchy and provocative as it is, relates as disposition to essence quite as surely as if I had tried to argue that it was Emily Brontë’s authorized version, or rather what she intended and could not perfectly execute.

This ‘tolerance to a wide variety of readings’ is attacked, with considerable determination, by E. D. Hirsch, committed as he is to the doctrine that the object of interpretation is the verbal meaning of the author; I think he would be against me in all details of the present argument. For example, he says quite firmly that interpretations must be judged entire, that they stand or fall as wholes; so that he could not choose, as I do, both to accept Mrs Leavis’s ‘realist’ reading and to reject her treatment of Heathcliff.6 But Hirsch makes a mistake when he allows that the ‘determinations’ (bestimmungen) of literary texts are more constrained than those of legal texts; and a further difficulty arises over his too sharp distinction between criticism and interpretation. In any case he does not convince me that tolerance in these matters represents ‘abject intellectual surrender’; and I was cheered to find him in a more eirenic mood in his later paper. He is surely right to allow, in the matter of meaning, some element of personal preference; the ‘best meaning’ is not uniform for all.

This being so one sees why it is thought possible, in theory at any rate, to practise what is called ‘literary science’ as distinct from criticism or interpretation: to consider the structure of a text as a system of signifiers, as in some sense ‘empty’, as what, by the intervention of the reader, takes on many possible significances.7 To put this in a different way, one may speak of the text as a system of signifiers which always shows a surplus after meeting any particular restricted reading. It was Lévi-Strauss who first spoke of a ‘surplus of signifier’ in relation to shamanism, meaning that the patient is cured because the symbols and rituals of the doctor offer him not a specific cure but rather a language ‘by means of which unexpressed, and otherwise inexpressible, psychic states can be immediately expressed’.8 Lévi-Strauss goes on to make an elaborate comparison with modern psychoanalysis. But as Fredric Jameson remarks, the importance of the concept lies rather in its claim for the priority of the signifier over the signified: a change which itself seems to have offered a shamanistic opportunity for the expression of thoughts formerly repressed.9

The consequences for literary texts are much too large for me to enter on here; among them, of course, is the bypassing of all the old arguments about ‘intention’. And even if we may hesitate to accept the semiological method in its entirety we can allow, I think, for the intuitive rightness of its rules about plurality. The gap between text and meaning, in which the reader operates, is always present and always different in extent.10 It is true that authors try, or used to try, to close it; curiously enough, Barthes reserves the term ‘classic’ for texts in which they more or less succeed, thus limiting plurality and offering the reader, save as accident prevents him, merely a product, a consumable. In fact what Barthes calls ‘modern’ is very close to what I am calling ‘classic’, and what he calls ‘classic’ is very close to what I call ‘dead’.

There is, in much of the debate on these matters, a quality of outrageousness, of the outré, and there is no reason why this should not be taken into account. We should, however, recall that in any querelle it is the modern that is going to display it most palpably. The prime modern instance is the row between Raymond Picard and Roland Barthes, which followed the publication of Barthes’s Racine in 1963. The title of Picard’s brisk pamphlet puts the point of the quarrel with a familiar emphasis: Nouvelle Critique ou nouvelle imposture (1965), and it contrives to make Barthes sound like the critic, deplored by all though read by few, who said that Nelly Dean stood for Evil. Barthes makes of the violent but modest drama of Racine something unrestrainedly sexual; if the text doesn’t fit his theory he effects a ‘transformation’; he uses neologisms to give scientific dignity to absurdities, and makes of the work under consideration ‘an involuntary rebus, interesting only for what it doesn’t say’.11

Barthes’s reply is splendidly polemic; the old criticism takes for granted its ideology to the degree that it is unconscious of it; its vocabulary is that of a schoolgirl (specifically, Proust’s Gisèle, Albertine’s friend) seventy-five years ago. But the world has changed; if the history of philosophy and the history of history have been transformed, how can that of literature remain constant? Specifically the old criticism is the victim of a disease he calls asymbolie; any use of language that exceeds a narrow rationalism is beyond its understanding. But the moment one begins to consider a work as it is in

itself, symbolic reading becomes unavoidable. You may be able to show that the reader has made his rules wrong or applied them wrongly, but errors of this kind do not invalidate the principle. And in the second more theoretical part of this very notable document Barthes explains that in his usage a symbol is not an image but a plurality of senses; the text will have many, not through the infirmity of readers who know less history than Professor Picard, but in its very nature as a structure of signifiers. ‘L’œuvre propose; l’homme dispose.’ Multiplicity of readings must result from the work’s ‘constitutive ambiguity’, an expression Barthes borrows from Jakobson. And if that ambiguity itself does not exclude from the work the authority of its writer, then death will do so: ‘By erasing the author’s signature, death establishes the truth of the work, which is an enigma.’12

I have suggested that the death of readers is equally important, as a solvent of generic constraints. However much we know about history we cannot restore a situation in which a particular set of arbitrary rules of a probability system is taken for granted, internalized. To this extent I am firmly on Barthes’s side in the dispute; and I have found much interest in his later attempts – which don’t, however, command anything like total agreement – to describe the transcoding operations by which, in contemplating the classic, we filter out what can now be perceived as mere ideological deposits and contemplate the limited plurality that remains.13

Barthes denies the charge that on his view of the reading process one can say absolutely anything one likes about the work in question; but he is actually much less interested in defining constraints than in asserting liberties. There are some suggestive figures in his recent book Le Plaisir du texte (1973), from which we gather that authorial presence is somehow a ghostly necessity, like a dummy at bridge, or the shadow without which Die Frau ohne Schatten must remain sterile; and these are hints that diachrony, a knowledge of transient dispositions, may be necessary even to the nouvelle critique competently practised. Such restrictions on criticism à outrance can perhaps only be formulated in terms of a theory of competence and performance analogous to that of linguistics.

Though I am more than half-persuaded (largely by Dr Jonathan Culler) that such a theory could be constructed, I am certainly not to

speak of it now. It will suffice to say that in so far as it is thought possible to teach people to read the classics it is assumed that knowledge of them is progressive. The nature of that knowledge is, however, as Barthes suggests, subject to change. Secularization multiplies the world’s structures of probability, as the sociologists of religion tell us, and ‘this plurality of religious legitimations is internalized in consciousness as a plurality of possibilities between which one may choose’.14 It is this pluralism that, on the long view, denies the authoritative or authoritarian reading that insists on its identity with the intention of the author, or on its agreement with the readings of his contemporaries; or rather, it has opened up the possibilities, exploited most aggressively by the structuralists and semiologists, of regarding the text as the permanent locus of change; as something of which the permanence no longer legitimately suggests the presence and permanence of what it appears to designate.

I notice in a very recent book on The Early Virgil – though it is by no means a Formalist or Structuralist study – what seems a characteristic modern swerve in the interpretation of the Fourth Eclogue; the author believes that the puer is the poem itself, that the prophecy relates to a new golden age of poetry, an age which the Eclogue itself inaugurates; and this, like the author’s remarks on the self-reflexiveness of the whole series of eclogues, seems modern, for it insists in some measure on the literarity of the work, its declared independence of the support of external reference. Even the arithmological elements in its construction serve to confirm it in this peculiar status.15 And we see how sharply this form of poetic isolation differs from the privileged status accorded the Eclogue by the ‘imperialist’ critics: there would be, for Mr Berg, no question of Christian prophecy in the Eclogue – there is not even any question of a reference to some recent or impending political event involving Antony or Octavius or Pollio himself. By the same token no interpretation of Virgil which depends on the assumption, in however sophisticated a form it may be presented, that his imperium was to be transformed into the Christian Empire, his key words – amor, fatum, pietas, labor – given their full significance in an eternal pattern of which he could speak without actual knowledge, would be acceptable to this kind of criticism. When we say now that the writer speaks more than he knows we are merely using an archaism; what we mean is that

the text is under the absolute control of no thinking subject, or that it is not a message from one mind to another.

The classic, we may say, has been secularized by a process which recognizes its status as a literary text; and that process inevitably pluralized it, or rather forced us to recognize its inherent plurality. We have changed our views on change. We may accept, in some form, the view proposed by Michel Foucault, that our period-discourse is controlled by certain unconscious constraints, which make it possible for us to think in some ways to the exclusion of others. However subtle we may be at reconstructing the constraints of past epistèmes, we cannot ordinarily move outside the tacit system of our own; it follows that except by extraordinary acts of divination we must remain out of close touch with the probability systems that operated for the first readers of the Aeneid or of Wuthering Heights. And even if one argues, as I do, that there is clearly less epistemic discontinuity than Foucault’s crisis-philosophy proposes, it seems plausible enough that earlier assumptions about continuity were too naïve. The survival of the classic must therefore depend upon its possession of a surplus of signifiers; as in King Lear or Wuthering Heights this may expose them to the charge of confusion, for they must always signify more than is needed by any one interpreter or any one generation of interpreters. We may recall that, rather in the manner of Mrs Leavis discarding Heathcliff, George Orwell would have liked King Lear better without the Gloucester plot, and with Lear having only one wicked daughter – ‘quite enough’, he said.

If, finally, we compare this sketch of a modern version of the classic with the imperial classic that occupied me earlier, we see on the one hand that the modern view is necessarily tolerant of change and plurality whereas the older, regarding most forms of pluralism as heretical, holds fast to the time-transcending idea of Empire. Yet the new approach, though it could be said to secularize the old in an almost Feuerbachian way, may do so in a sense which preserves it in a form acceptable to changed probability systems. For what was thought of as beyond time, as the angels, or the majestas populi Romani, or the imperium were beyond time, inhabiting a fictive perpetuity, is now beyond time in a more human sense; it is here, frankly vernacular, and inhabiting the world where alone, we might say with Wordsworth, we

find our happiness – our felicitous readings – or not at all. The language of the new Mercury may strike us as harsh after the songs of Apollo; but the work he contemplates stands there, in all its native plurality, liberated not extinguished by death, the death of writer and reader, unaffected by time yet offering itself to be read under our particular temporal disposition. ‘The work proposes; man disposes.’ Barthes’s point depends upon our recalling that the proverb originally made God the disposer. The implication remains that the classic is an essence available to us under our dispositions, in the aspect of time. So the image of the imperial classic, beyond time, beyond vernacular corruption and change, had perhaps, after all, a measure of authenticity; all we need do is bring it down to earth.