7. The Middle/Upper Palaeolithic Transition in Northern and Southern Israel: A Technological Comparison

Josette Sarel and Avraham Ronen

Introduction

Garrod and Neuville were the first to subdivide the Levantine Upper Palaeolithic, establishing a six-phase unilinear sequence that begins with a ‘transitional’ phase (Neuville 1934; Garrod 1951, 1954. Neuville called it ‘Phase I’ and Garrod called it ‘Emiran’). Raqefet Cave, on the eastern side of Mount Carmel, northern Israel displays industries containing both Mousterian and Upper Palaeolithic implements that underlie Levantine Aurignacian layers (Noy unpublished report). These assemblages, which are marked by the association of Levallois implements and Upper Palaeolithic laminar products, are similar to those defined as ‘transitional’ or ‘Emiran’ by Garrod and Neuville, such as those from the caves of Emireh, el-Wad G, F and Kebara E.

The mixed nature of this ‘transitional’ phase has raised the problem of its credibility. It was suggested that erosion and major karstic activities at the end of the Mousterian had disturbed the archaeological beds in northern Israel and were responsible for these mixed assemblages (Bar-Yosef and Vandermeersch 1972). Nevertheless, a ‘transitional’ phase, well stratified at Ksar Akil (Copeland 1975) and Boker Tachtit (Marks 1983a, c), has been recognized.

Today, scholars are well aware of cave formation processes and more attention is paid to the geological contexts of the archaeological record. The studies of sediments and mineral assemblages in Hayonim and Kebara caves (Weiner et al. 1995; Goldberg and Bar-Yosef 1998) have revealed the complexity of the site formation and post-depositional processes within caves in northern Israel, that can significantly influence the archaeological layers. Anthropogenic, geogenic and biogenic processes can all displace artefacts to varying extents (Goldberg and Bar-Yosef 1998). This tends to support the postulate that the ‘transitional’ assemblages in northern Israel are the outcome of such processes (Bar-Yosef and Vandermeersch 1972). Nevertheless, ‘transitional’ assemblages were uncovered in sites where no significant disturbances were reported, such as Umm el-Tlel in Syria (Boëda and Muhesen 1993), Ksar Akil in Lebanon (Copeland 1975), and Boker Tachtit in southern Israel (Marks 1983a, c). This fact leads us to raise doubts as to the extent and impact of post-depositional processes in the caves of northern Israel. It is possible that erosional events and karstic activities occurred within the ‘transitional’ layers and not between the Mousterian and the Upper Palaeolithic horizons. Thus the assemblages exhibiting both Levallois products and Upper Palaeolithic-type blades are not necessarily the result of mechanical admixtures, but could testify for the existence of the ‘transitional’ phase, as it was previously perceived by Garrod and Neuville.

To validate the occurrence of ‘transitional’ assemblages in northern Israel, it is necessary both to determine the site formation processes in each cave, and to analyze the possible cultural relationships between them and the Lebanese, Syrian and southern Israeli ‘transitional’ industries.

In this paper we present our preliminary analysis of the Levallois and laminar cores and tools of the ‘transitional’ phases of Raqefet Cave, and compare the results with those from other northern Israeli assemblages, as well as from Ksar Akil in Lebanon, and Boker Tachtit in southern Israel.

Some scholars use the term ‘Initial Upper Palaeolithic’ as it appears to be a neutral term compared with the term ‘transitional phase’ previously used, which implies a phylogenetic relationship between the Mousterian and the Upper Palaeolithic (Kuhn et al. 1999). Others use the term ‘Intermediate Period’, which does not relate the assemblages to either the Middle or the Upper Palaeolithic (Boëda and Muhesen 1993). The term ‘late Mousterian’ (Moustérien tardif) has been employed recently because of the Levallois implements that characterize this industry (Bourguignon 1996:317–336). In the present paper, the original term ‘transitional’ is used for convenience, but it does not imply any cultural continuity.

Levallois and Laminar Knapping

Levallois flaking

The definition of the Levallois method is still considered controversial. According to Bordes, the Levallois method is aimed at the morphology of the desired products and the predetermined shape is attained by prior removals (Bordes 1980). For Boëda, Levallois flaking follows a particular volumetric concept of the core that consists of the preparation of two asymmetric convex surfaces defining a plane of intersection. One serves as a striking platform from which the other is flaked. Boëda identifies two methods of exploitation in the Levallois system: the preferential and recurrent methods (Boëda 1986, 1995a). Following him, we recognize six types of Levallois core (Fig. 7.1). The Levallois flakes are defined according to the classical definition of Bordes (1980):

1.A. In the preferential Levallois method, a single flake is manufactured from each prepared flaking surface and it removes most of this surface:

1.A.1: Preferential quadrangular Levallois core.

1.A.2: Preferential triangular Levallois core.

1.B. In the recurrent Levallois method, a series of flakes is manufactured from each prepared removal surface:

1.B.1: Recurrent unipolar Levallois core. Flakes are detached from a single striking platform. The negative removals visible on the upper surface have parallel or convergent directions.

1.B.2: Recurrent bipolar Levallois core. A series of predetermined flakes is derived from two opposed striking platforms; the negative removals visible on the upper surface of the core have parallel and opposed directions.

1.B.3: Recurrent centripetal Levallois core. The circumference of the entire surface of the core is used as the striking platform. For each preparation of the core, a series of centripetal flakes is detached.

1.C. Indeterminate Levallois core. These are broken or burnt items on which the flaking method cannot be defined.

There are no laminar Levallois cores in the ‘transitional’ assemblages.

Laminar flaking

Blade production displays ‘Upper Palaeolithic’ features in the flaking organization of the cores, such as in the convexity of preparations (i.e., the preparation of crests, edge abrasion and removal of core tablets for platform maintenance and rejuvenation) and the common use of soft stone or soft hammer techniques. The identification of these techniques is based on criteria defined after knapping experiments (Pelegrin 1997). Blades can be produced from cores with one or more striking platforms.

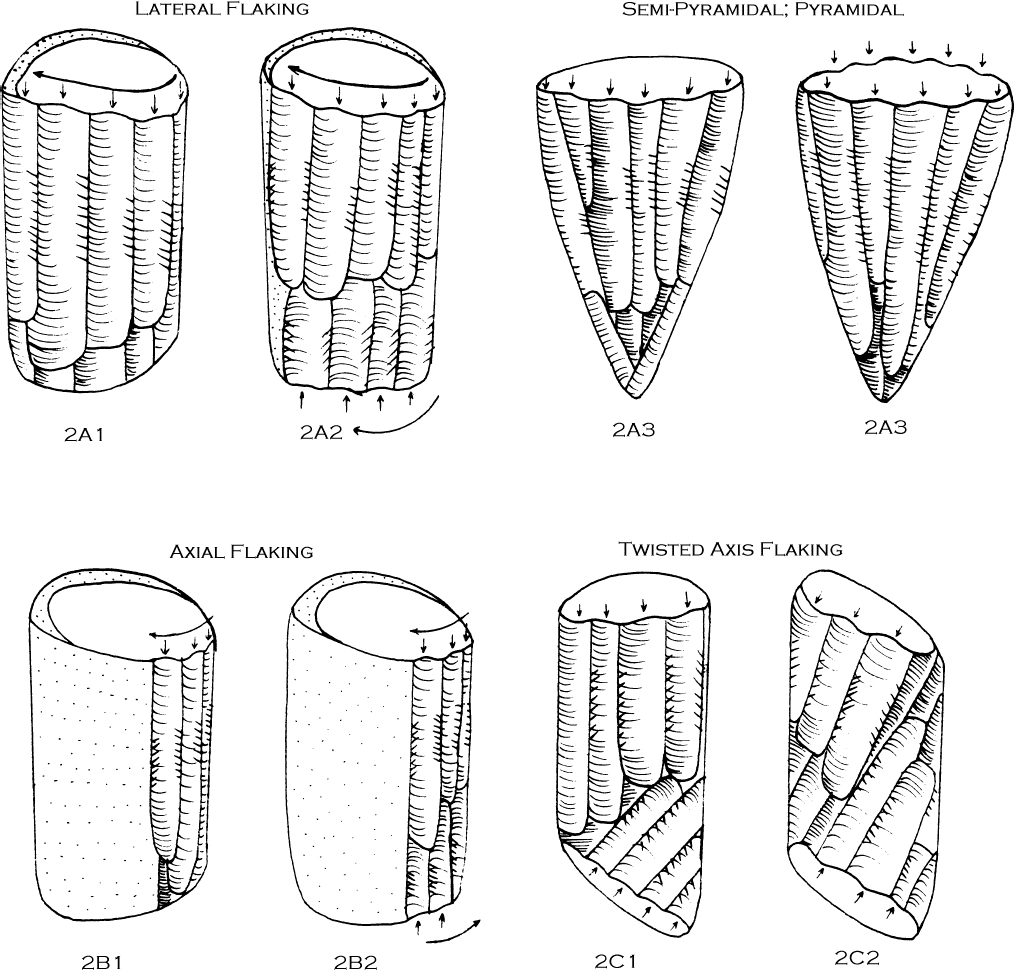

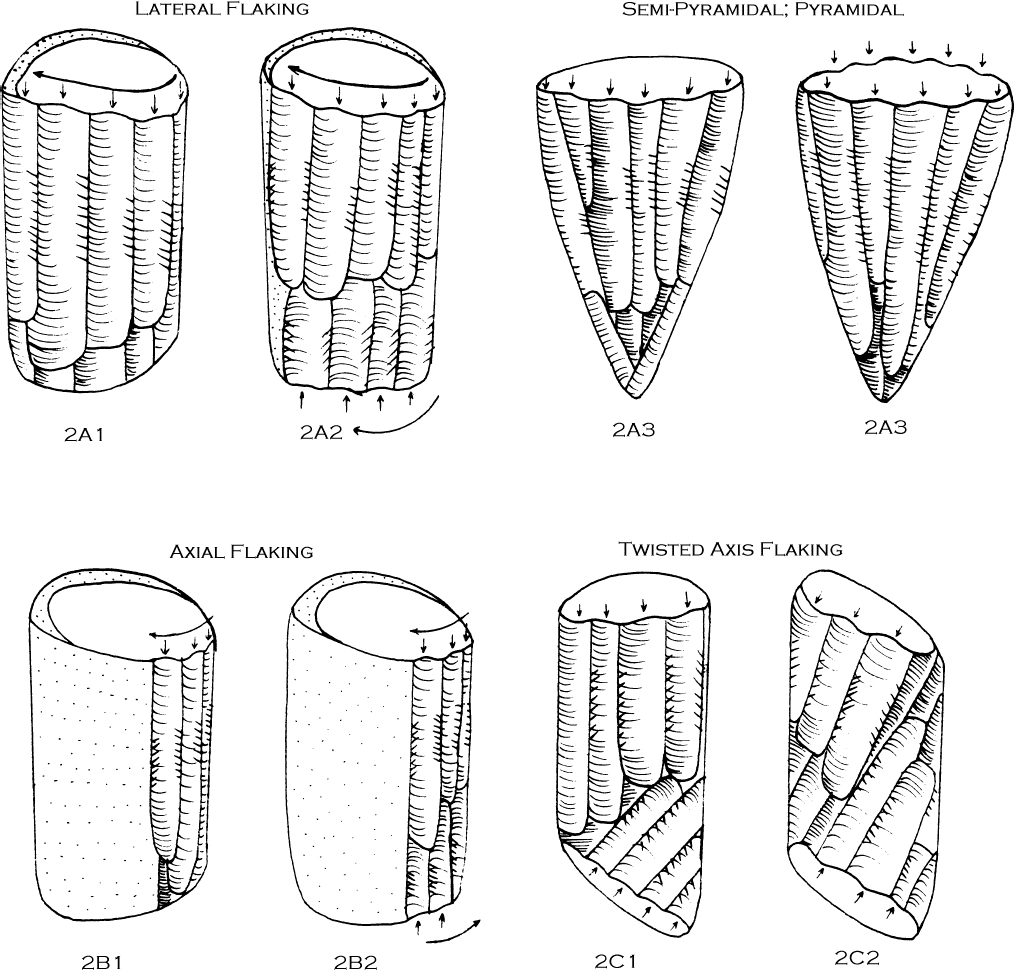

We present here the main categories of the blade cores that we have defined, according to the location of both the striking platforms and the removal surface of the cores. When flaking affects the lateral, widest part of the core, we call it a ‘lateral-flaking core’. When it is restricted to the narrowest part of the core, we call it an ‘axial-flaking core’. And when two striking platforms are involved, which are oriented on different axes of the core, we call it a ‘twisted, two striking platform core’. We recognize eight types of Upper Palaeolithic blade cores (Fig. 7.2):

2.A. Single striking platform blade cores

2.A.1: Lateral flaking core with one striking platform. The lateral flaking starts from the narrow axis edge and extends towards the lateral, widest part of the core. The edge commonly has a natural, dihedral morphology as do flake cores, and thus cresting is unnecessary.

2.A.2: Axial flaking core with one striking platform. Flaking is restricted to the narrow axis of the core, but can extend a little towards the two lateral sides, and the striking platform is always oriented on the same axis of the core. Thus the specific location of the platform, in relation to the axis, remains unchanged throughout the whole knapping process.

2.A.3: Pyramidal or semi-pyramidal core. The core has a pyramidal shape and the removal of blades affects mostly the periphery of the core. When the removal of the blades affects only half of the periphery of the core, we call it a semi-pyramidal core.

2.B. Two opposed striking platforms oriented on the same axis blade cores

2.B.1: Opposed, lateral striking platform core oriented on the same axis. The lateral flaking starts from the narrow axis edge and extends towards the lateral edge of the core, which is always the widest part. Only one striking surface is exploited and the series of blades are removed alternately from the two opposed striking platforms.

2.B.2: Axial flaking core with two opposed platforms. Flaking is restricted to the narrow axis of the core, but can extend a little towards the two lateral sides. Thus, the specific location of the platforms, in relation to the axis, remains unchanged throughout the whole knapping process. Series of blades are removed alternately from the two opposed striking platforms.

2.C. Twisted opposed platforms blade cores

2.C.1: Axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking core. The striking surface is divided into two unequal flaking surfaces, which have opposite flaking directions. The axial flaking surface is usually the main one, as it covers most of the removal surface and the lateral flaking surface is restricted to a small part of the striking surface. These two flaking surfaces maintain lateral and distal convexities, permitting more efficient blade production.

2.C.2: Bi-directional, opposed lateral flaking core. The removal surface is divided into two equal portions, which have opposed flaking directions. The two flaking surfaces maintain lateral and distal convexities, enabling more efficient blade production.

2.D. Indeterminate blade core. These are broken or burnt items for which the flaking method cannot be defined.

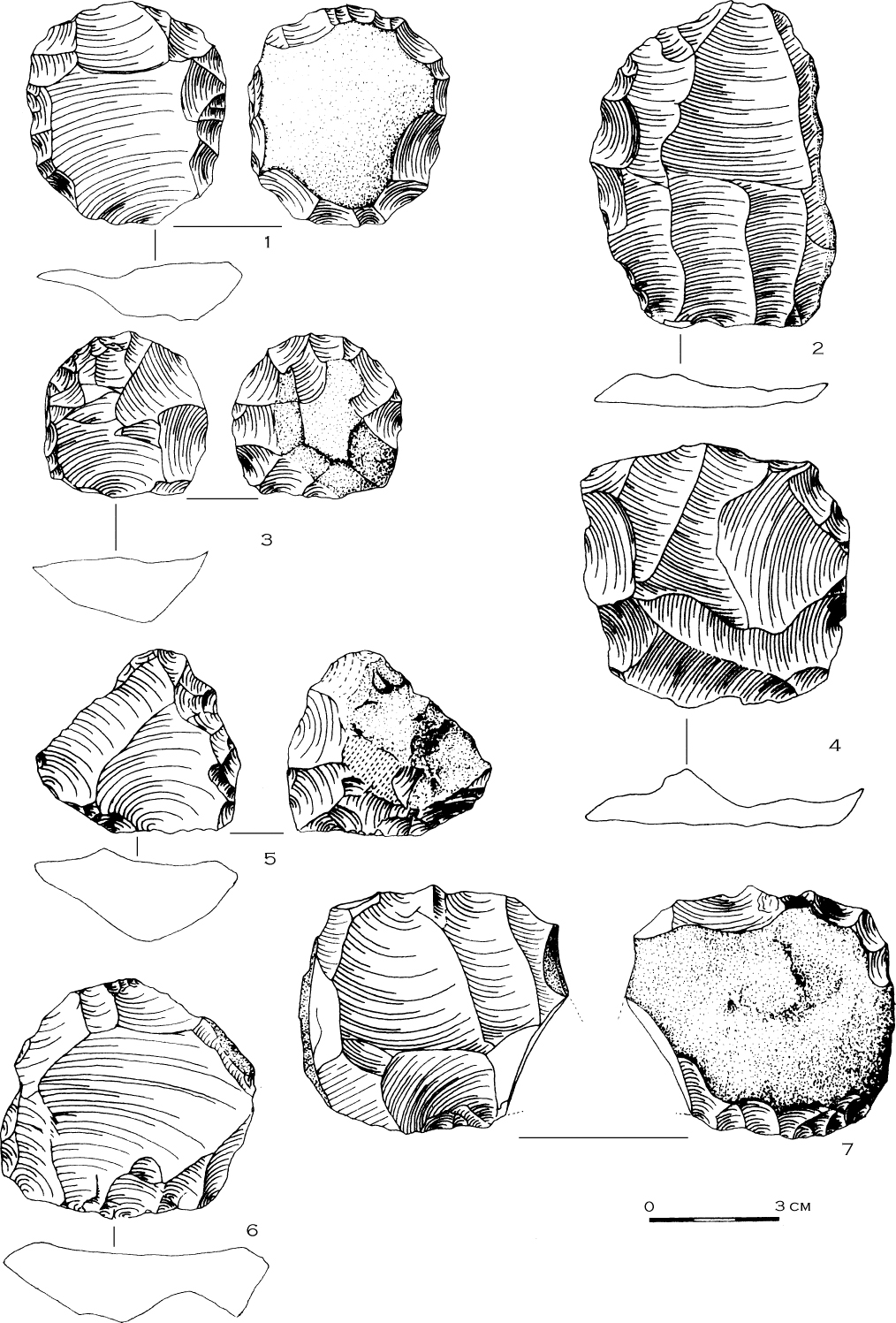

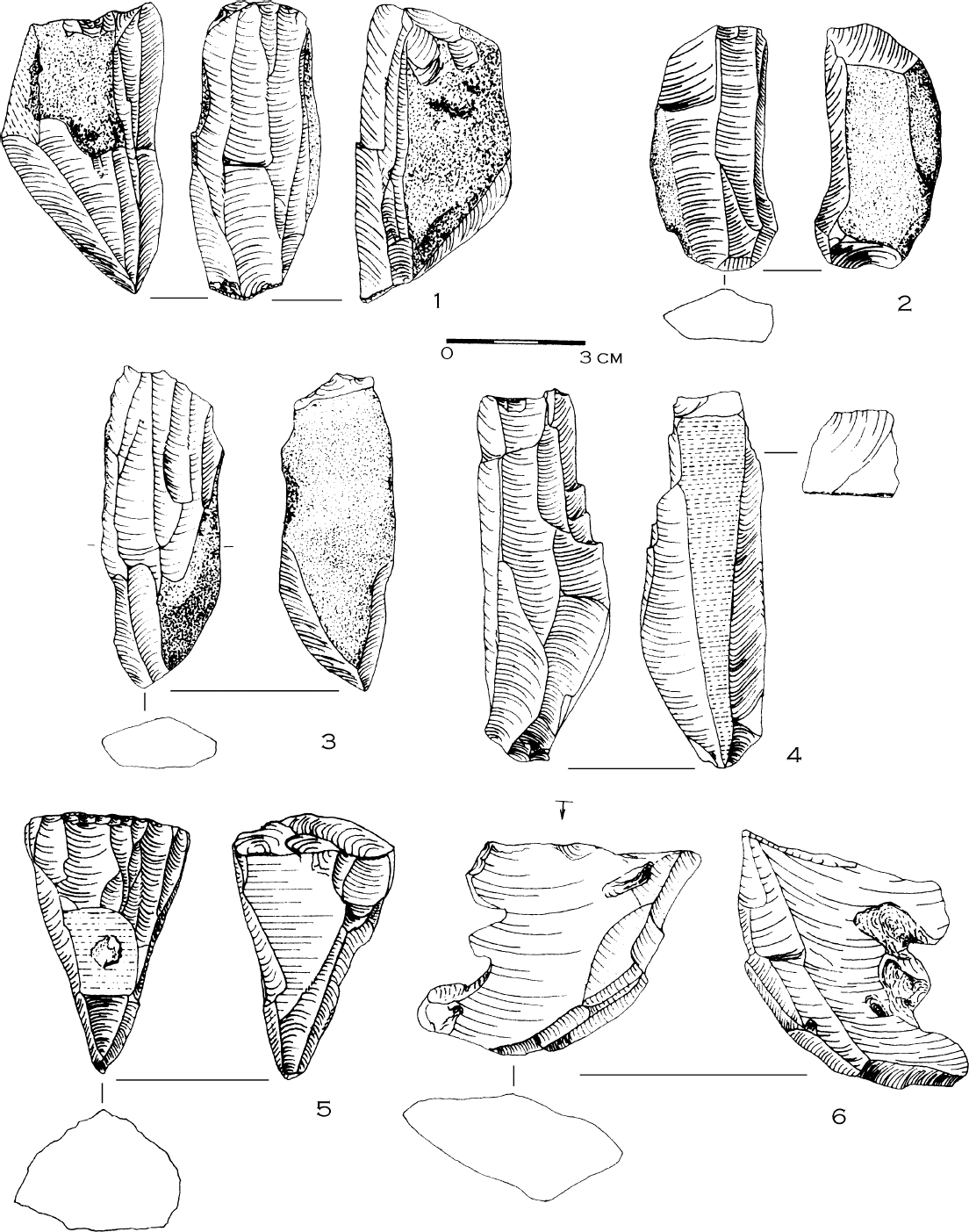

Fig. 7.1 Levallois core types: 1, Preferential flake core (Emireh); 2, Recurrent bipolar core (el-Wad F); 3, Recurrent centripetal core (Emireh); 4, Recurrent centripetal core (el-Wad F); 5, Recurrent unipolar core (Raqefet VII); 6, Recurrent bipolar core (Raqefet VII); 7, Recurrent unipolar core (Kebara E).

Fig. 7.2 Schematic illustrations of blade core categories: 2A1, Lateral core with single striking platform; 2A2, Axial core with single striking platform; 2A3, Pyramidal and semi-pyramidal cores; 2B1, Lateral, opposed platform core oriented on the same axis; 2B2, Opposed platform core oriented on the same axis; 2C1, Twisted opposed platform core with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking; 2C2, Twisted opposed platform core with opposed lateral flaking.

The ‘Transitional’ Phase at Raqefet

Raqefet Cave is situated in a west-facing cliff above Nahal Raqefet, Mount Carmel, Israel. Noy and Higgs excavated the site in 1970–72. Unfortunately, Noy did not complete her analyses of the material. Nevertheless, Noy and Higgs prepared a detailed report on the excavations, which is used in the present study (Noy and Higgs unpublished report).

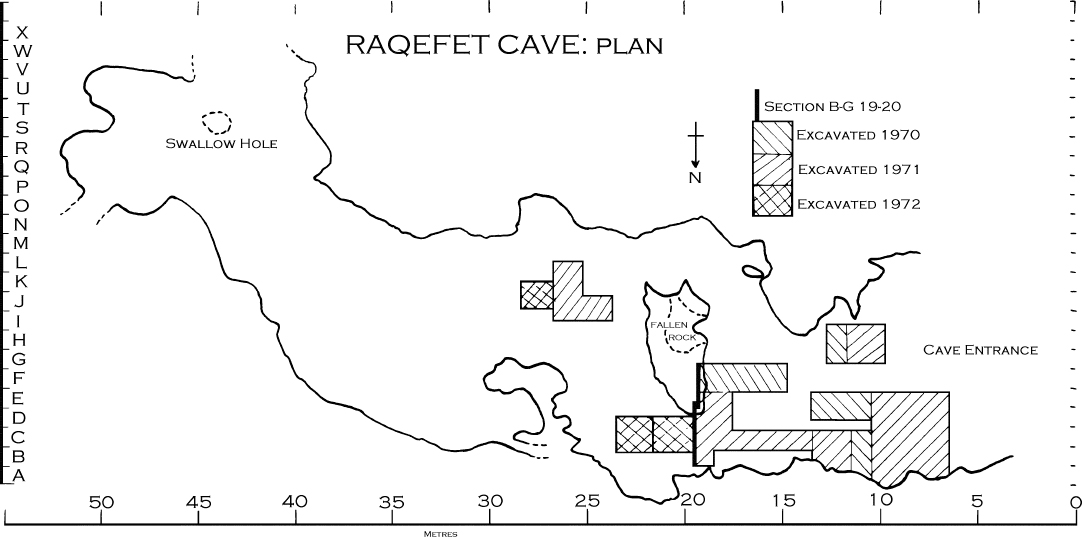

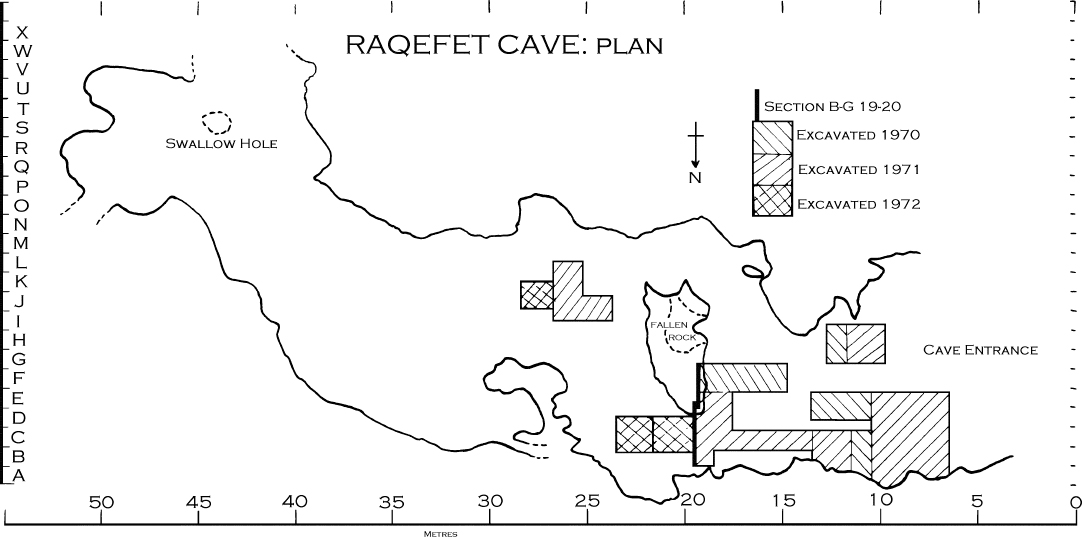

The karstic cave consists of a chamber about 45 m long and 17 m wide, leading to a rear chamber ca. 8 m long and 13 m wide (Fig. 7.3). The cave has been eroded from a vertical joint and there is a chimney in the rear chamber that breaks through to the surface. A large rock-fall has blocked off much of the light to the rear half of the site.

Fig. 7.3 Plan of the Raqefet excavations (after Noy and Higgs unpublished report).

The site extends over a maximum area of some 500 m2. The excavations were largely confined to the front chamber of the cave and divided into three areas (B-G/18–23, A-H/7–17 and J-M/24–28). The excavators were unable to establish stratigraphic correlations between these areas. The surface of the excavations amounted to 55 m2 with a maximum depth of about 2.5 m. The three areas yielded Neolithic, Natufian and Kebaran occupations, but only squares C-D/18–20 and E-F/18–19 from the area B-G/18–23, were excavated down to bedrock, revealing four ‘transitional’ layers (VIII–V), 40–60 cm thick, which underlie two Upper Palaeolithic layers (IV–III). We assigned the four lower layers (VIII–V), which contain Mousterian implements associated with a blade-oriented technology to the ‘transitional phase’. Layers IV–III were attributed by the excavators to the Levantine Aurignacian on the basis of the presence of typical Aurignacian tools (nosed, shouldered and carinated scrapers) and by the absence of Levallois implements.

The stratigraphy of Raqefet is very complex. The cave shows evidence of heavy erosive activity and the burrows present in some squares seem to have influenced the composition of the layers. The majority of flint shows varying degrees of abrasion, and in some squares (especially in squares D-E/19–20) concentrations of lithic material occur. This suggests that water and/or rodent burrowing have displaced some artefacts. In all layers there is burnt material.

Degree of Artefact Abrasion

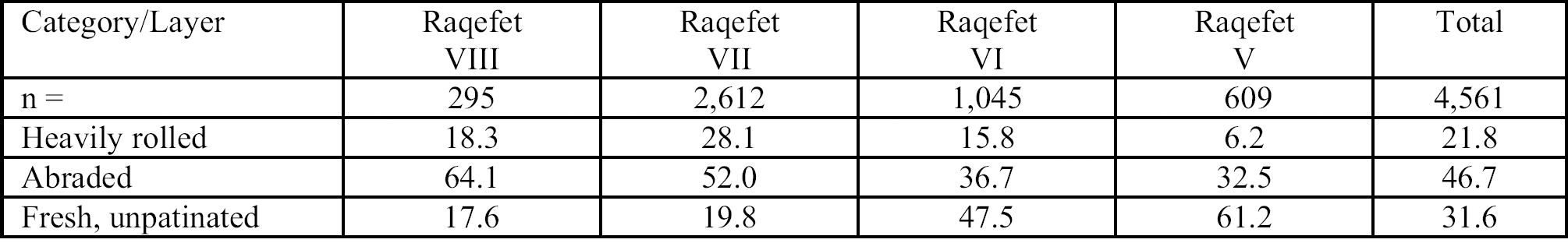

In order to determine the effects of erosion on the artefacts in Raqefet in the ‘transitional’ layers, the tools, debitage and cores from area B-G/18–23 were divided into three abrasion categories:

A.Heavily rolled material. The artefacts are rounded and the scar removals are not visible.

B. Abraded material with strong patination. However, the material is not rounded and removal scars are still clear.

C. Fresh, unpatinated material.

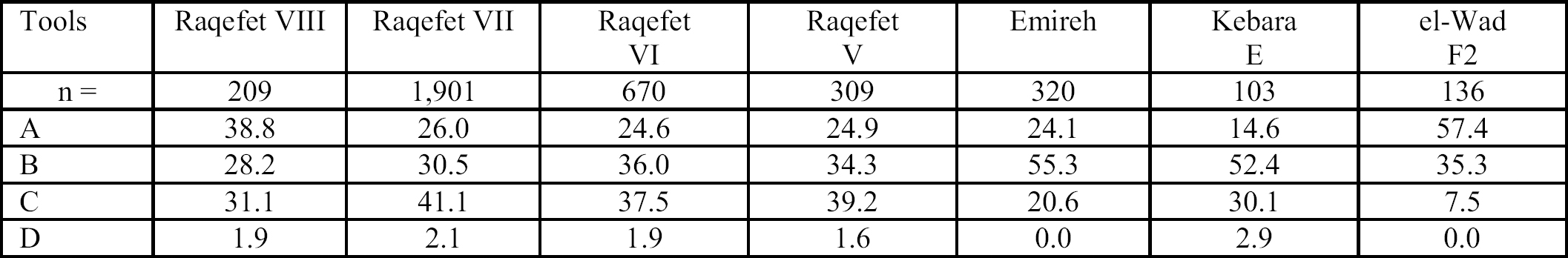

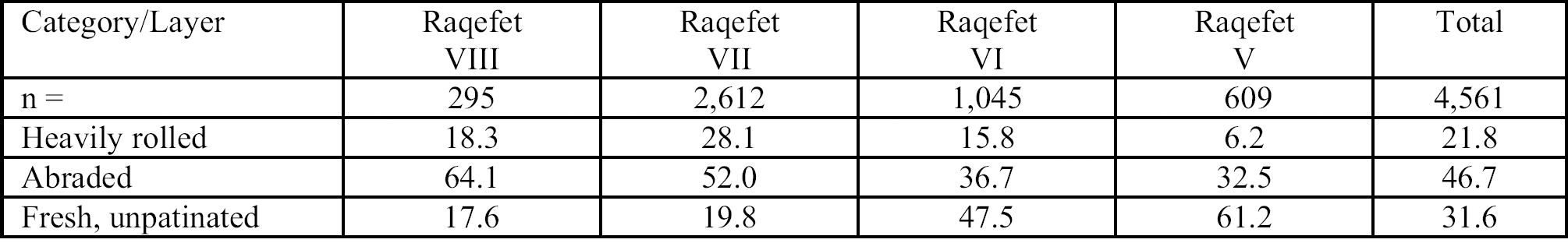

For the purposes of this analysis, we considered the frequency of each abrasion group in different squares from each level. Both fresh and rolled implements are present in each square of all four layers. The most noteworthy observation concerns the relative proportions of the three preservation categories between the laminar and Levallois products, which do not change significantly within each layer; they have more or less comparable percentages in the different squares of the same layer, except for Square D20 in layer VII. Nevertheless, the relative frequencies of the three types do change from one layer to the next. The percentage of fresh implements tends to increase from bottom to top (17.6% in layer VIII, 47.5% in layer VI and 61.2% in layer V) (Table 7.1) and the Aurignacian layers (IV and III) contain only fresh material. Square D20, which yielded large quantities of artefacts, contains more rolled material in layer VII, when compared with the material from the other squares of the same layer. It thus seems that the disturbance is most pronounced in the lower layers (VIII and VII).

Table 7.1 Frequency distributions of the degree of abrasion of artefacts* from Raqefet Cave.

*The artefacts include tools, debitage and cores

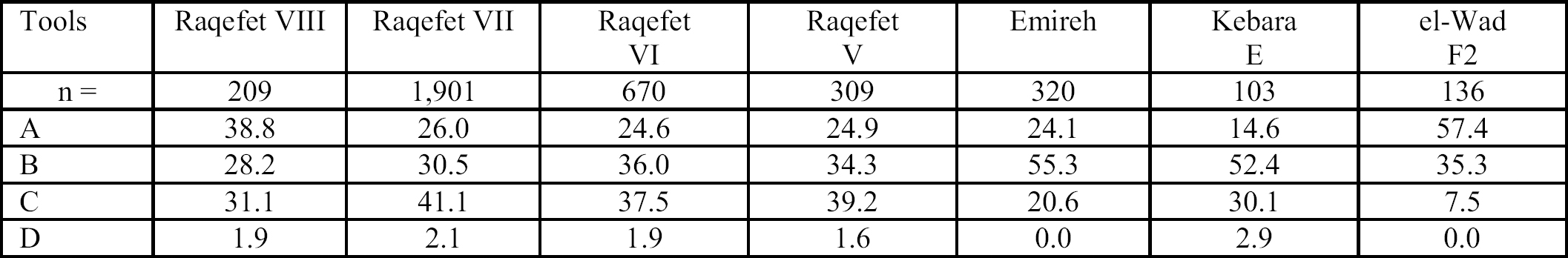

Table 7.2 Frequencies of Levallois, laminar, and non-Levallois tools in the ‘transitional’ layers of sites in northern Israel.

Key: A, Levallois tools; B, Blade tools; C, Non-Levallois flake tools; and D, Indeterminate

Despite the lack of geological data, we can suppose that erosion and karstic activities occurred during the ‘transitional’ phase in Raqefet. The degree of abrasion is similar in both laminar and Levallois products, while the distributions of the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic type implements remain more or less constant in the different squares and layers.

Lithic Industries from the ‘Transitional’ Phase: Layers VIII–V

The ‘transitional’ layers are marked by the presence of Levallois methods, as well as non-Levallois flake and blade reduction strategies. The percentages of Levallois and blade tools remain more or less constant in the three ‘transitional’ upper layers of Raqefet (Layers VII–V). In Layer VIII, Levallois tools outnumber blade tools (Table 7.2).

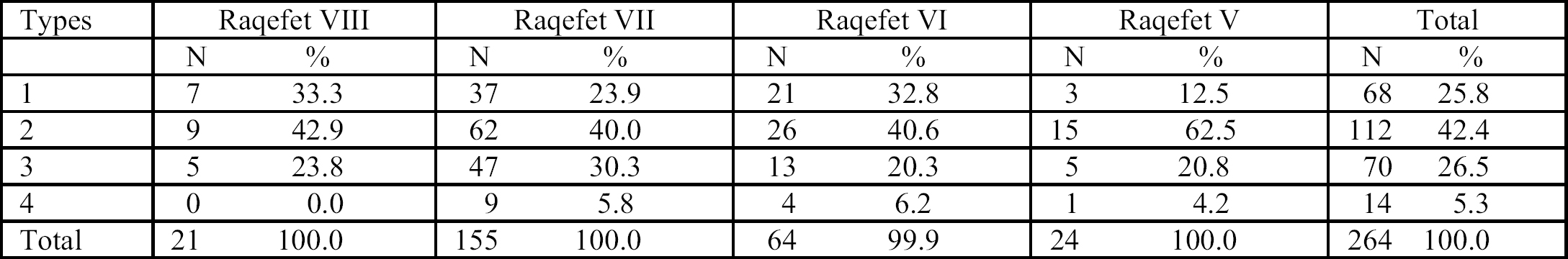

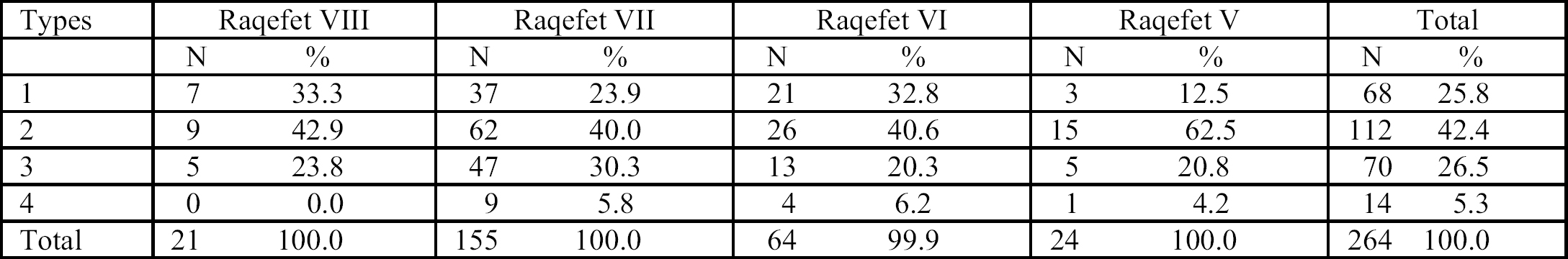

In all these layers blade cores dominate. Their frequencies, which remain more or less constant in Layers VIII–VI with ca. 40%, attain 62.5% in Layer V. The Levallois cores account for ca. 30% in Layers VIII–VI, but they decrease in Layer V, with 12.5% (Table 7.3).

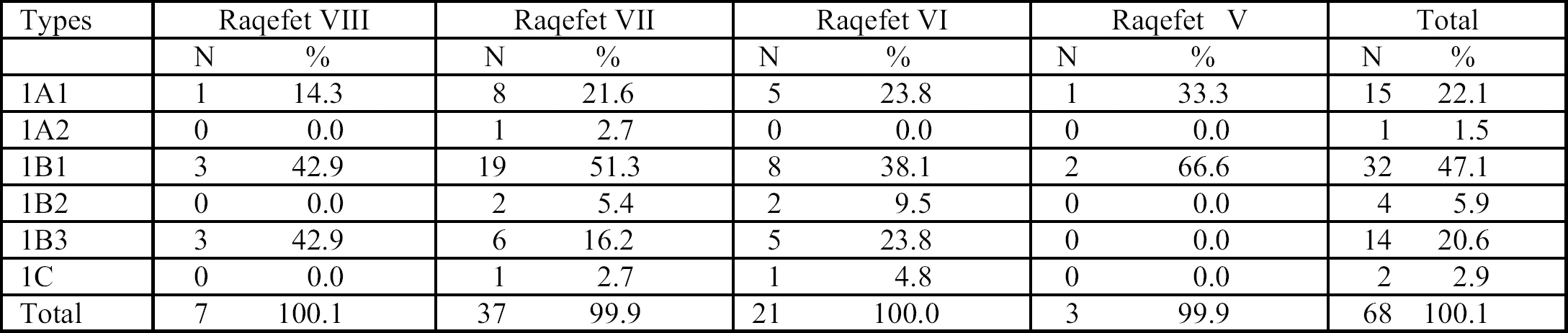

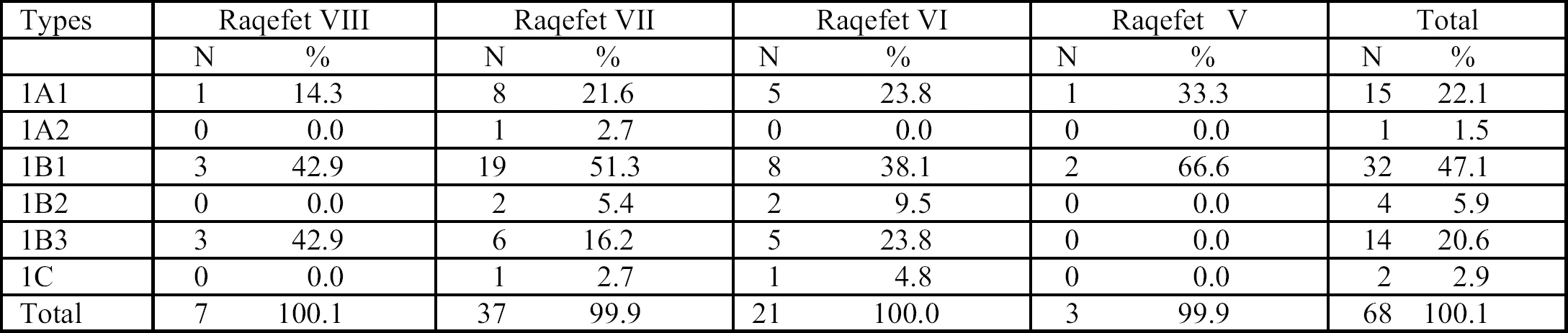

Levallois Flaking (Table 7.4): the preferential Levallois method is well represented amongst the Levallois cores (23.6%) in the ‘transitional’ layers. Among the preferential Levallois cores, the quadrangular flake cores are the main group, while triangular flake cores are poorly represented. However, it is the recurrent Levallois cores that are always dominant in these layers. Among them, recurrent unipolar cores represent 47.1% (Fig. 7.1:5), the recurrent centripetal cores 20.6%, and the bipolar cores 5.9% (Fig. 7.1:6). According to the flake scar orientations on some flakes, it is likely that some recurrent convergent unipolar Levallois cores were further reduced through a centripetal method toward the end of their exploitation. Some Levallois cores are broken or burnt and the flaking method cannot be defined. Side-scrapers, points and denticulates are the main tool types among the Levallois blanks.

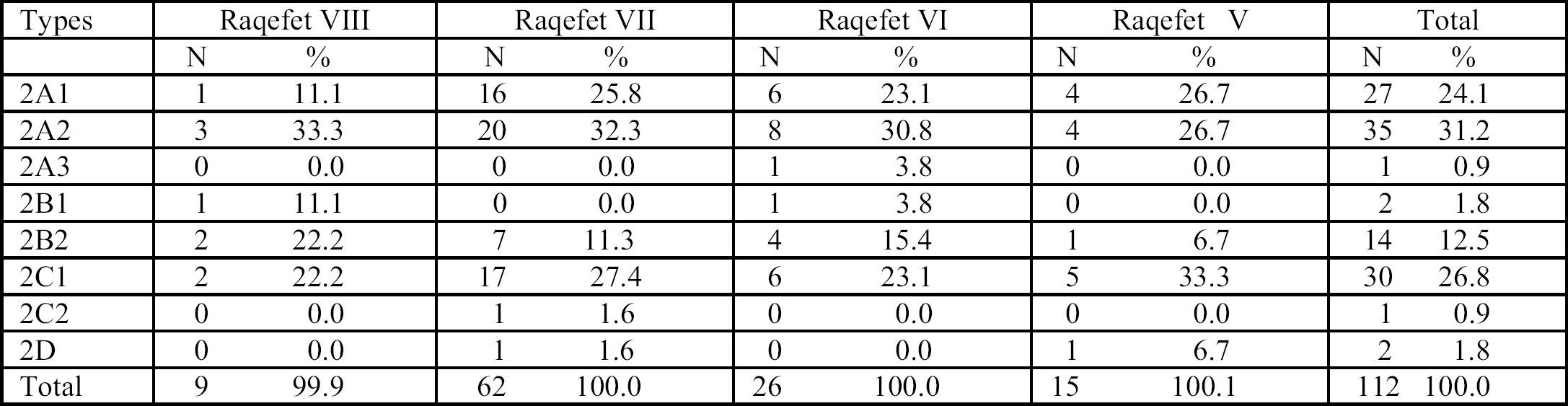

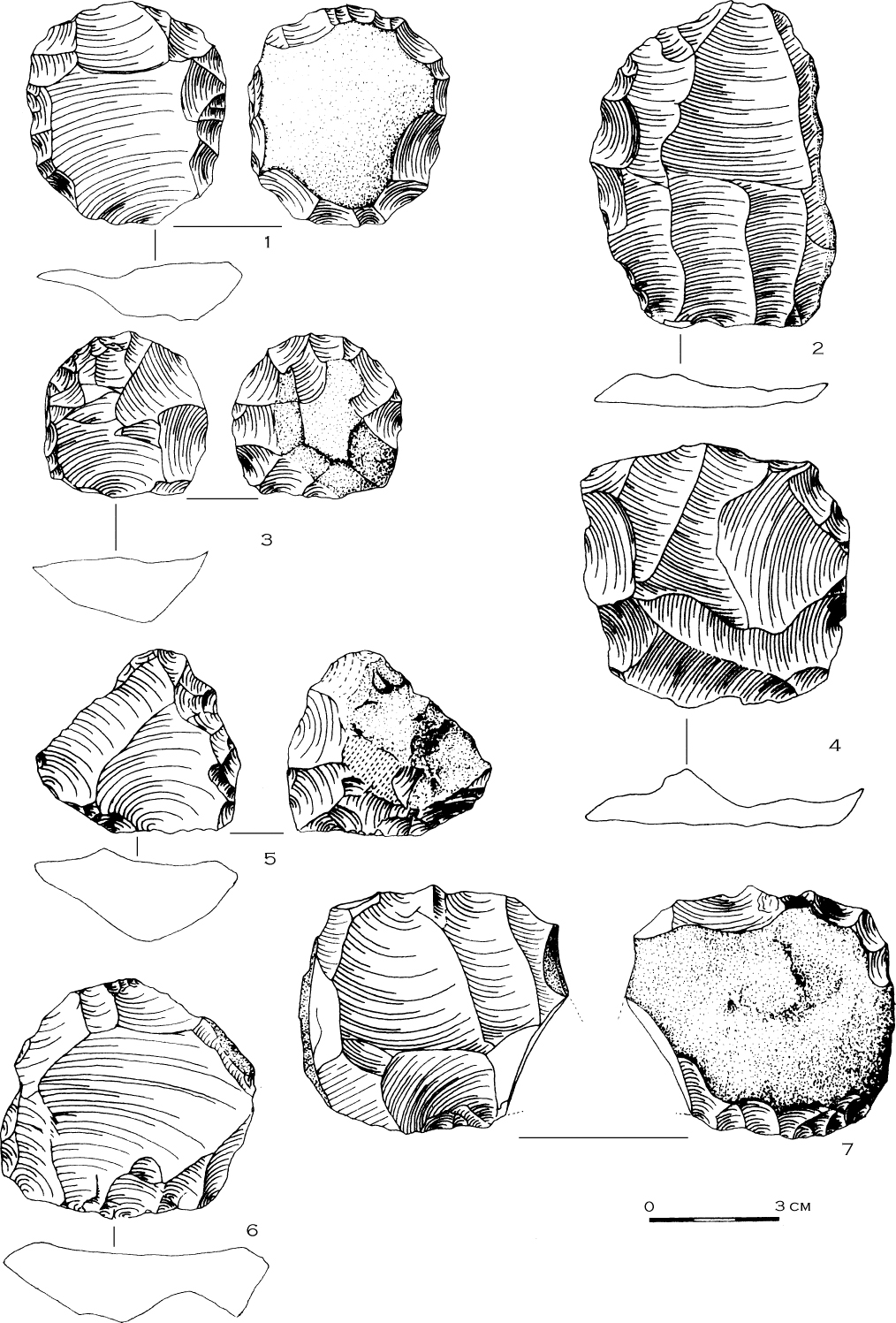

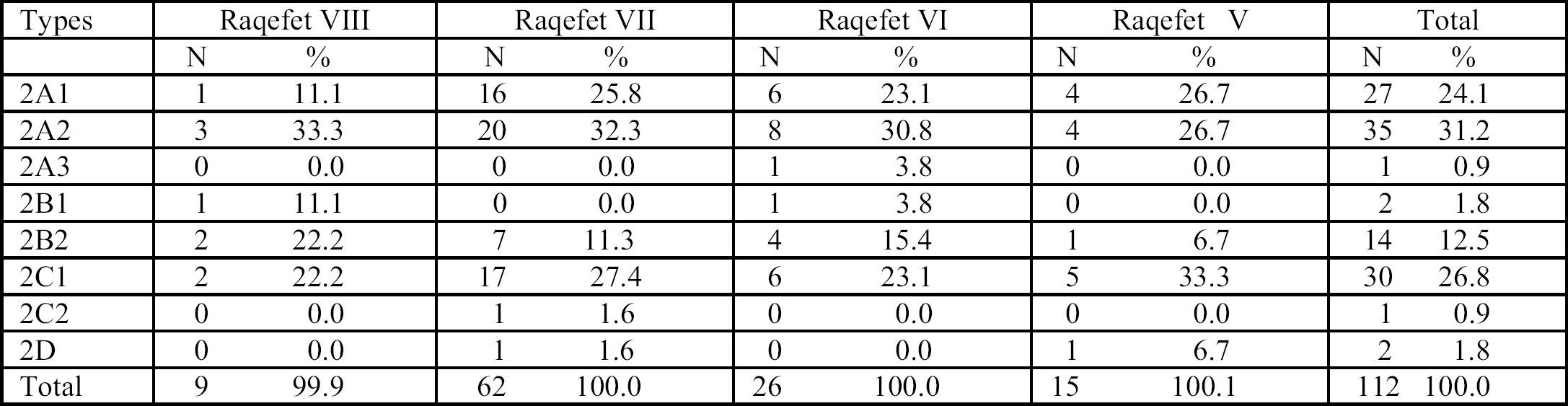

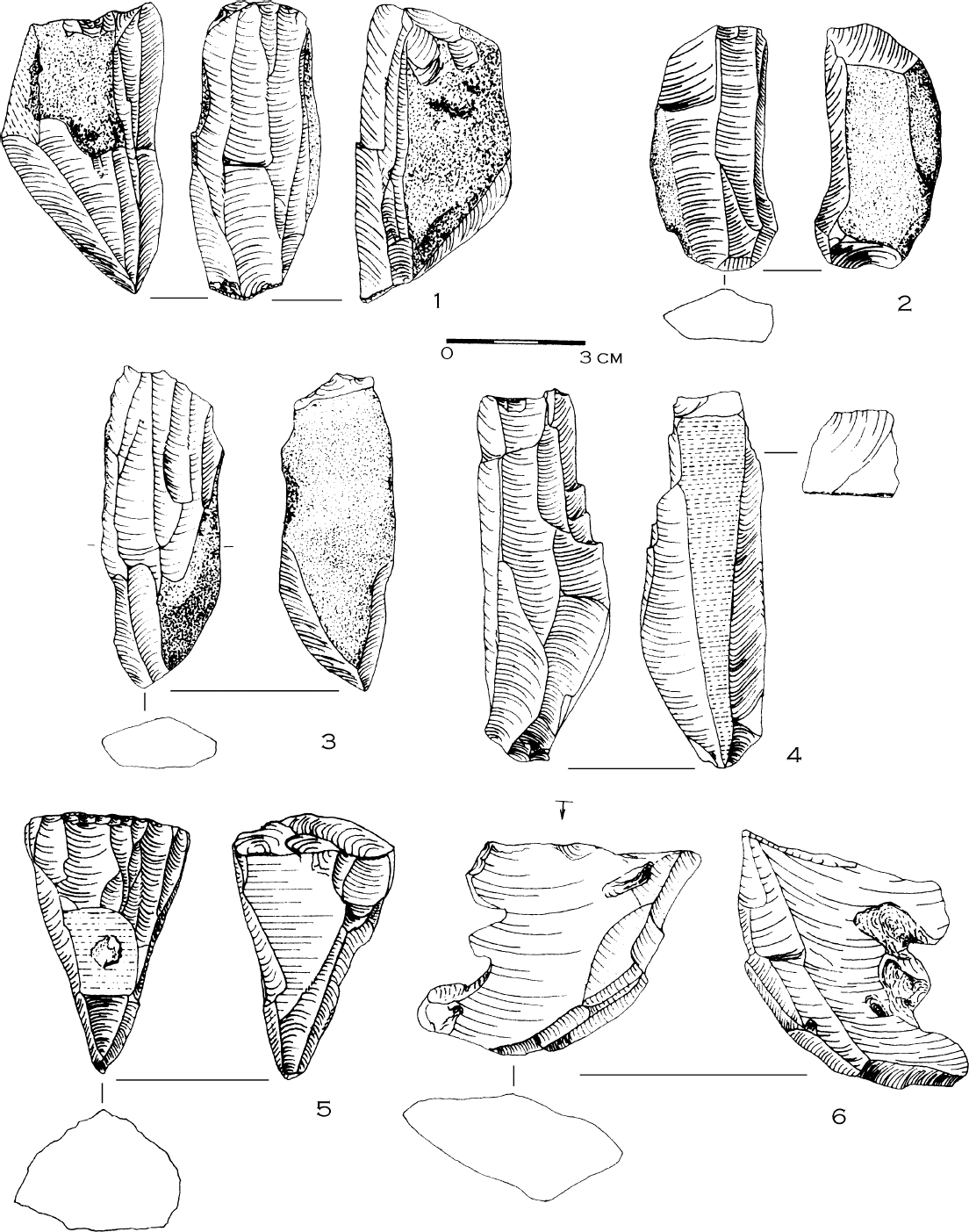

Laminar Flaking (Table 7.5): there is no significant difference among the ‘transitional’layers except for the single striking platform cores, which slightly dominate in the three upper layers (ca. 55%), especially the axial flaking core with one platform (31.2%). The lateral flaking cores with one platform are well represented (24.1%) and pyramidal or semi-pyramidal cores are rare. Opposed platform cores dominate in Layer VIII (56%). Two twisted striking platform cores with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking, are well represented (26.8%) (Fig. 7.4:3). The opposed platform core, oriented on the same axis, also occurs (12.5%) (Fig. 7.4:1). The core can be on a flake, in which case the flaking is restricted to the side of the flake (Fig. 7.4:5). The bi-directional opposite lateral flaking cores (0.9%) and the lateral flaking on opposed striking platform core, oriented on the same axis (1.8%), are poorly represented.

It is worth noting the relation between the morphology of the blanks and the flaking method. Rounded nodules are the raw material generally selected for the one or two opposed striking platform core with twisted-axes. Tabular flint or thick flakes are most often used for the one or two opposed striking platforms with axial flaking or lateral flaking cores. According to the scars visible on some striking platforms and the orientation of the blade removals, it seems that products were more frequently removed by soft or soft stone hammer in a tangential motion. On some cores, the use of both a hard and soft stone hammer is likely, and can be connected with different sequences in the reduction strategy. The blade tool assemblage consists of high frequencies of retouched pieces, notches and denticulates, as well as simple endscrapers, truncated pieces and perforators. The el-Wad points, burins, carinated and nosed endscrapers occur in a low frequency. Bladelets are poorly represented, accounting for 1.8% of the tools, representing mainly retouched bladelets, endscrapers and truncated bladelets.

Table 7.3 Levallois, laminar and non-Levallois cores in the ‘transitional’ layers of Raqefet.

Key: 1, Levallois cores; 2, Non-Levallois blade cores; 3, Flake cores; 4, Indeterminate cores

Table 7.4 Levallois core categories in the ‘transitional’ layers of Raqefet.

Key: 1A1, Preferential quadrangular flake core; 1A2, Preferential triangular flake core; 1B1, Recurrent unipolar core; 1B2, Recurrent bipolar core; 1B3, Recurrent centripetal core; 1C, Indeterminate core

Table 7.5 Laminar core categories in the ‘transitional’ layers of Raqefet.

Key: 2A1, Lateral flaking core with single striking platform; 2A2, Axial flaking core with single striking platform; 2A3, Pyramidal or semi-pyramidal core; 2B1, Lateral opposed platform core oriented on the same axis; 2B2, Opposed platform core oriented on the same axis; 2C1, Twisted opposed platform core with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking; 2C2, Twisted opposed platform core with bi-directional opposed lateral flaking; 2D, Indeterminate blade core.

Fig. 7.4 Blade core types: 1, Opposed platform core oriented on the same axis (Raqefet VIII); 2, Twisted opposed platform core with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking (el-Wad F); 3, Twisted opposed platform core with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking (Raqefet VII); 4, Twisted opposed platform core with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking (Emireh); 5, Semi-pyramidal core (Kebara E); 6, Opposed platform core oriented on the same axis (on flake, Raqefet VIII).

Emireh

Emireh Cave is located in the Rift Valley, lower Galilee, Israel. The site revealed a Palaeolithic layer covered by some Neolithic remains and recent deposits. The sediments, which averaged 70 cm in thickness, extended in part down to bedrock. Garrod, who published the material, assigned it to the ‘transitional’ Emiran industry (Garrod 1955). The total collection includes 706 pieces. For this study, 657 implements were examined from the Rockefeller Museum, as well as a small sample kept in the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine in Paris.

Levallois Flaking: of the 37 cores, 16 (43%) are of Levallois type. The recurrent centripetal Levallois method is dominant among the Levallois cores (Fig. 7.1:3). Products of preferential Levallois flake cores (Fig. 7.1:1) and of the recurrent, mostly convergent, unipolar cores occur, but the recurrent bipolar Levallois method is absent. The assemblage contains 24.1% Levallois tools (Table 7.2). Sidescrapers, points and denticulates are the main tool types. Four Emireh points are present in this assemblage.

Laminar Flaking: of the 37 cores, 17 (46%) were used to produce blades. Among the laminar cores, blade production from two striking platform cores dominates, particularly those with twisted axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking (Fig. 7.4:4). Semi-pyramidal or pyramidal cores are also present. The lateral flaking type is poorly represented. Blade blanks generally have small plain butts, with traces of abrasion on the edge, indicating the use of a soft or soft stone hammer. Among the 320 tools examined in this assemblage, the laminar index forms 55.3% (Table 7.2). Narrow blades and bladelets have been made into endscrapers, el-Wad points or retouched tools. Large blade points, denticulates, sidescrapers and end-scrapers have been manufactured on large triangular blades with facetted butts. It is possible that these blanks were removed from pyramidal cores by direct percussion using a hard stone hammer.

El-Wad

El-Wad Cave is located in Wadi el-Mughara, Mount Carmel. The excavations, which took place in the cave and on the terrace, revealed an important succession of layers. Garrod first interpreted the sequence as Mousterian (layer G) covered by Upper Palaeolithic deposits (layers F, E, D and C). Later, she changed her interpretation and assigned layers G and F to a single cultural unit defined as a ‘transitional’ industry (Garrod and Bate 1937; Garrod 1951:121–130). The material from el-Wad is stored in different museums all over the world. For this study, the implements stored in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem, and at the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine in Paris were examined. Only the results from the analysis of layer F2 are presented here, which constitutes a small part of the assemblage. Of 1,056 pieces from F2, we examined 198 tools and cores, which represent 18.8% of Garrod’s collection. This assemblage consists of blades and Levallois products, with the presence of the Emireh point. The predominant raw material in this industry occurs in the form of medium or small nodular flint of local origin, less frequently on large nodules or pebbles. All of these were used for the production of both Levallois and laminar blanks.

Levallois Flaking: among the 62 cores, 47 (76%) are Levallois. The Levallois debitage of preferential flake core type dominates. The recurrent centripetal (Fig. 7.1:4) and unipolar convergent cores are well represented. The recurrent bipolar Levallois method also occurs (Fig. 7.1:2). Levallois tools represent 57.4% of the tools examined. Sidescrapers, denticulates, and retouched flakes are well represented among the tools. Garrod reported five Emireh points in el-Wad G-F (Garrod 1955:142)

Laminar Flaking: of the 62 cores, 13 (21%) were used to produce blades. The nodules are generally smaller than those from Emireh. They are most often rounded and cortical. Among the laminar cores, two striking platform varieties are well represented, especially those with twisted axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking (Fig. 7.4:2). Lateral flaking cores occur, and the semi-pyramidal or pyramidal cores are poorly represented. Laminar tools form 35.3% of the sample. Among the 48 tools examined, denticulates and retouched blades are well represented. The blade blanks generally have small plain butts, with traces of abrasion on the edge, attesting to the use of a soft or soft stone hammer utilized in a tangential motion.

Kebara

The cave, situated in Mount Carmel, has been excavated several times and is a key site for defining the cultural sequence of the Upper Palaeolithic in the Levant. The excavations revealed Early Natufian, Kebaran (Turville-Petre 1932; Garrod and Bate 1937), later Upper Palaeolithic (Garrod 1954), and Mousterian layers (Schick and Stekelis 1977). More recently, the site has been reexcavated with greater stratigraphic precision (Bar-Yosef et al. 1992, 1996; Goldberg and Bar-Yosef 1998). Four Upper Palaeolithic units were distinguished overlying the Mousterian. Units III–IV were assigned to the Ahmarian, and Units I–II to the Levantine Aurignacian (Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1996).

We present here a sample of the Upper Palaeolithic assemblage (layer E) from the Turville-Petre excavation. This assemblage of 469 items was divided in 1931 into three approximately equal lots (Garrod 1954:156). A lot of 137 items housed at the Rockefeller Museum was examined here.

The sample contains both Levallois flakes and Upper Palaeolithic blades. The Levallois tools comprise 14.6% and the blade tools 52.4% of the assemblage (Table 7.2). Of the 22 cores, two are Levallois cores (9.1%), 19 are blade cores (86.4%) and one is a non-Levallois flake core (4.5%). According to the blade industry that characterizes this assemblage, Bar-Yosef et al. (1996:302) suggest that layer E should be correlated with Units IV and III of the new excavations.

Levallois Flaking: only two cores were found in this assemblage. One is a recurrent unipolar (Fig. 7.1:7) and the other is a preferential Levallois core. Among the tools on Levallois flakes, points and sidescrapers dominate.

Laminar Flaking: among the laminar cores, blade production from two platform cores represent 48%. The axial double core with one striking platform and the two twisted striking platform cores with axial flaking opposed to lateral flaking dominate. The semi-pyramidal or pyramidal cores are well represented (Fig. 7.4:6), while lateral flaking hardly occurs. Among the tools on blade/lets examined, points, endscrapers and retouched blades are the main tool types. The blade blanks generally have small plain butts, with traces of abrasion on the edge. It seems that the products from layer E were more frequently removed by soft stone hammer, or soft hammer.

Ksar Akil

Ksar Akil is a rockshelter situated in Wadi Antelias in Lebanon. The site was discovered in 1922 and excavated in 1937–38 under the direction of J.G. Doherty from Boston College, Massachusetts, then in 1947–48 by J.F. Ewing who established a stratified sequence of 34 levels (Ewing 1947; 1949), and later, in 1969–75, by J. Tixier (1974). The site of Ksar Akil revealed 22 m of archaeological deposits, beginning with Mousterian levels and ending with Kebaran strata. The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transitional layers (XXV–XIV) yielded about 4 m of deposits, including both Levallois implements and Upper Palaeolithic blades. These levels were divided into Phases A and B (Copeland 1975; 1986). We studied samples of 374 cores from the Doherty and Ewing excavations housed in the British Museum, London and present here the preliminary results. This material was studied previously by Azoury (1986) and Ohnuma (1988).

Phase A (levels XXV–XXI) overlies the Mousterian levels and contains Levallois and non-Levallois laminar products. Among the 289 cores examined from Phase A, 10.7% are Levallois cores, 79.2% are laminar cores and 10.0% are other flake cores. The recurrent unipolar Levallois method is mostly used and recurrent bipolar Levallois cores are well represented. Blade production from single platform cores is dominant. Axial flaking cores dominate and pyramidal and semi-pyramidal cores are present. The technique used is essentially hard hammer. The main tools are elongated triangular points, endscrapers and chamfered blades. Levallois points, sidescrapers, notches and denticulates are poorly represented (Azoury 1986; Ohnuma 1988).

Phase B (levels XX–XIV) underlies the Aurignacian layers from which it is separated by the artefact-poor level XIV. Azoury divided this phase between Phase IIA (levels XX–XIX) and Phase IIB (levels XVIII–XV), according to the presence or absence of tools such as the el-Wad point (Azoury 1986). Among the 85 cores examined from Phase B, 9.4% are Levallois cores, 85.9% are laminar cores and 4.7% are other flake cores. These levels exhibit both Levallois and blade implements. Nevertheless, some technological and technical differences with Phase A can be noticed. The blades are detached mostly from opposed platform cores and the bipolar cores with twisted-axes dominate. Pyramidal or semi-pyramidal cores are not represented. Moreover, soft hammer was used for detaching blades. The main tools are endscrapers and el-Wad points; notches and denticulates occur but chamfered pieces are absent (Azoury 1986; Ohnuma 1988).

According to these preliminary results, it seems that the assemblages of Phase B exhibit similar features to those from northern Israel. We describe below the main characteristics of these assemblages.

Characteristics of the Northern ‘Transitional’ Industries

Raqefet VIII–V, Emireh, el-Wad F, Kebara E and Ksar Akil Phase B, have yielded assemblages sharing a number of features, such as the association of Upper Palaeolithic blade and Levallois products and similar reduction strategies. In all these assemblages, the preferential and recurrent unipolar methods are mainly used among the Levallois cores; and the twisted platform cores with axial opposed to lateral flaking are mostly dominant among the laminar cores. The single platform core with axial flaking is also well represented. The methods used to produce blades are most often related to the morphology of the raw material. Lateral and axial flaking is frequently used with flat nodules, tabular flint or thick flakes, while twisted axial flaking is employed for the rounded nodules. The Levallois blanks were usually used to produce sidescrapers, endscrapers, points, denticulates and retouched flakes. The blade tool components usually consist of retouched blades, notches and denticulates, endscrapers and points. The laminar products indicate the use of hard and soft hammer or soft stone hammers.

The ‘Transitional’ Industries from Boker Tachtit

Boker Tachtit is situated on the east bank of Nahal Zin in the central Negev, Israel. The site was excavated in 1975 and 1980 (Marks 1977a, 1983a). Four occupation layers have been observed. Levels 1–3 have been related to the ‘transitional’ phase and level 4 (the uppermost layer) to the Upper Palaeolithic (Marks and Volkman 1983; Marks and Kaufman 1983). Systematic core reconstruction has enabled the determination of the main reduction strategies employed in these four levels. They attest to a period of rapid technological change from a specialized Levallois-based core reduction strategy to a single platform core reduction strategy (Volkman 1983). This change consisted of a shift from a homogeneous Levallois-based technology (level 1) to a period of great heterogeneity and flexibility in technology (levels 2 and 3), ending with another homogenous, but non-Levallois based, single platform blade technology (level 4) (Volkman 1983:130). We examined a sample of 115 cores from Boker Tachtit housed at the Israeli Antiquities Authority, and we present here the preliminary results.

In the three transitional lower levels (1–3), opposed platform cores dominate. Most of them exhibit opposed striking platforms oriented on the same axis. Also present, to a lesser degree, are twisted striking platform cores with axial opposed to lateral flaking. The uppermost level (4) exhibits different reduction strategies. The axial-flaking blade core with single platform dominates and the pyramidal core occurs. Most cores from these four levels display preparation of crested blades and the hard hammer percussion technique is used exclusively.

The ‘transitional’ industries from Lebanon, northern and southern Israel display both Levallois implements and Upper Palaeolithic blades. Are the Levallois and blade flaking methods in the north (including Ksar Akil) similar to those from Boker Tachtit? Are the north and the south culturally related?

Lebanon, Northern and Southern Israel ‘Transitional’ Industries Compared

The main difference between the assemblages in the north (including Ksar Akil) and the south concerns the Levallois reduction strategies. The northern industries exhibit Levallois cores compatible with Boëda’s definition. This is not the case at Boker Tachtit. Using Bordes’s definition of Levallois, Marks and Kaufman suggest that in Boker Tachtit ‘… the basic core reduction method is Levallois, in as much as there apparently was a desired end product of predictable shape; a shape predetermined by prior removals’ (Marks and Kaufman 1983:71). These cores described as Levallois show two main differences in reduction strategies in comparison to the other sites studied herein:

First, in the northern Levallois assemblages, the organization of the Levallois debitage always follows a particular volumetric concept of the core. The initialization phase prepares the core volume, comprising two asymmetric convex surfaces that form a plane of intersection. In order to create the convexities that permit detachment of the Levallois blank(s), the knapper removed débordant flakes or centripetal predetermining flakes, which are always secants to the intersection plane and are removed from the lateral and distal sides of the core (Boëda 1986, 1995a). In the Levallois cores from Boker Tachtit 1–3, the initialization phase is marked by the production of one or two crests situated on the upper and/or lower surfaces. The predetermining flakes that form the crest are not detached from the lateral or distal sides, as with the northern Levallois cores but from the upper side, along the long axis of the core.

Secondly, in the northern Levallois cores, the large surface of the core is selected as the flaking surface. In the Levallois cores from Boker Tachtit, the flaking surface is always the narrow side of the core. Because flaking is restricted to the narrow axis and the two striking platforms are oriented on the same axis, it is possible to consider them as axial flaking blade cores with two opposed platforms.

Among the Levallois cores of the north (including Ksar Akil), the recurrent centripetal and the unipolar types dominate, while they are totally absent in the south. One and two striking platform cores are well represented in the laminar cores of the northern industries. The twisted striking platform cores and the axial-flaking cores with one or two striking platforms dominate. Lateral flaking and the pyramidal cores occur less frequently. In Boker Tachtit levels 1–3 axial flaking blade cores with opposed platforms dominate. The single striking platform cores are less frequent and the twisted platforms core is absent.

Sidescrapers, points and denticulates constitute the main categories among the Levallois products of the northern assemblages; retouched blades, notches and denticulates are the main tool types among the laminar products. Some retouched bladelets occur in most of the assemblages. Levallois points, Emireh points, burins, notches and denticulates constitute the main tool types in Boker Tachtit levels 1–3. There are no bladelets or retouched bladelets at Boker Tachtit (Marks 1983a).

The techniques of soft or soft stone and hard hammer percussion are all attested in northern assemblages (including Ksar Akil), while at Boker Tachtit 1–4 only hard hammer percussion is used.

Conclusions

The northern and the Boker Tachtit assemblages presented herein have all been considered as ‘transitional’, since they display both Levallois and blade reduction strategies. Nevertheless, the technological differences described here lead us to suggest that it is not possible to relate the northern and southern industries to the same cultural entity. Even if we suppose that post-depositional processes did mix the Middle Palaeolithic and Upper Palaeolithic layers in the northern caves, the technological differences between the industries of the north and those of Boker Tachtit are still considerable.

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to thank E. Boëda for his suggestions and help. We would like to thank Hava Katz and Iris Yossifon from the Israel Antiquities Authority, for permission to examine the material stored in the Rockefeller Museum, as well as N. Ashton for providing us with facilities to study the Ksar Akil collections at the British Museum. Thanks are due to A.E. Marks for authorization to see the assemblages from Boker Tachtit. We are grateful to Paulina Spivak and Assaf Meshullam for drawing the lithic artefacts.

A special note of appreciation is due to the late Tamar Noy for granting us permission to work on the material from Raqefet and for giving us access to her valuable notes.