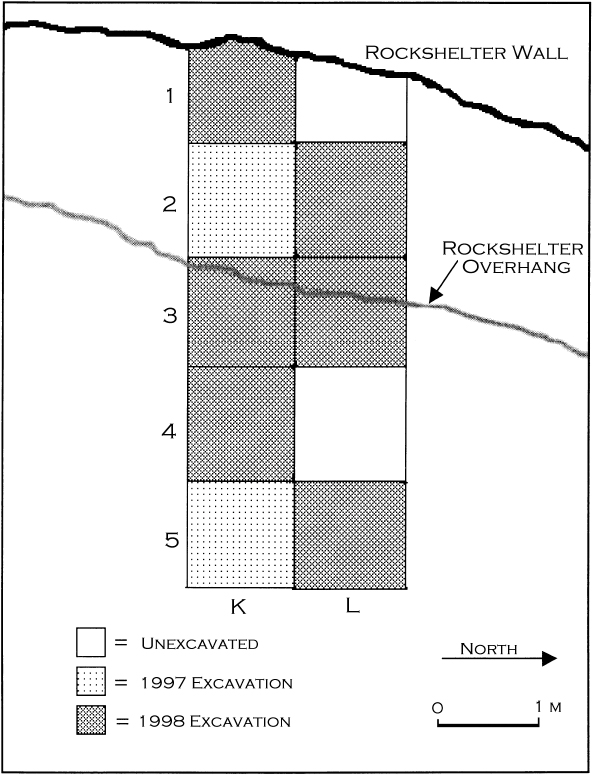

Fig. 8.1 Plan View of Excavation Units at Tor Sadaf.

In recent years archaeological investigations into the earliest Levantine Upper Palaeolithic have taken on increasing importance. Sites dating to this interval are quite rare, and our understanding is further confounded by a lack of reliable dates from such sites. As a result, the technological variability and chronology for this important phase of human cultural evolution are poorly understood. Through the use of a detailed technological analysis, this paper introduces evidence from the site of Tor Sadaf into our current database and also provides new insights into the technological evolution from a transitional, single platform technology with a number of Levallois-like characteristics, to a true blade technology. Tor Sadaf can be added to the list of sites where this shift has now been documented (Azoury 1986; Coinman and Henry 1995; Marks 1983c; Ohnuma and Bergman 1990). In addition, the sequence of occupation at Tor Sadaf may represent one of the only sites where an Early Ahmarian assemblage is found stratigraphically overlying materials of a transitional nature.

The rockshelter of Tor Sadaf was found during a survey of the north bank of the Wadi al-Hasa (Clark et al. 1992). The site consists of a small limestone overhang (extending less than 2 m from the parent rock), overlooking a tributary to the Wadi al-Misq (see Coinman this volume for map). The rockshelter overhang is formed on the strath bench of an extensive bed of fossil oystershell deposits (Schuldenrein in Olszewski et al. 1998). Lithic artefacts were concentrated on a relatively flat surface immediately below and in front of the rockshelter, extending down a steep talus to the nearby wadi bottom. In contrast to many Upper Palaeolithic sites in the Hasa area, Tor Sadaf is not located near the edge of the Pleistocene lake that dominated the larger Hasa Basin (Schuldenrein and Clark 1994). The distance to the main lake basin and the absence of lake sediments or remnant marls in the area of the site suggest that the site’s function may relate to another sort of resource zone, but palaeoenvironmental evidence is fragmentary.

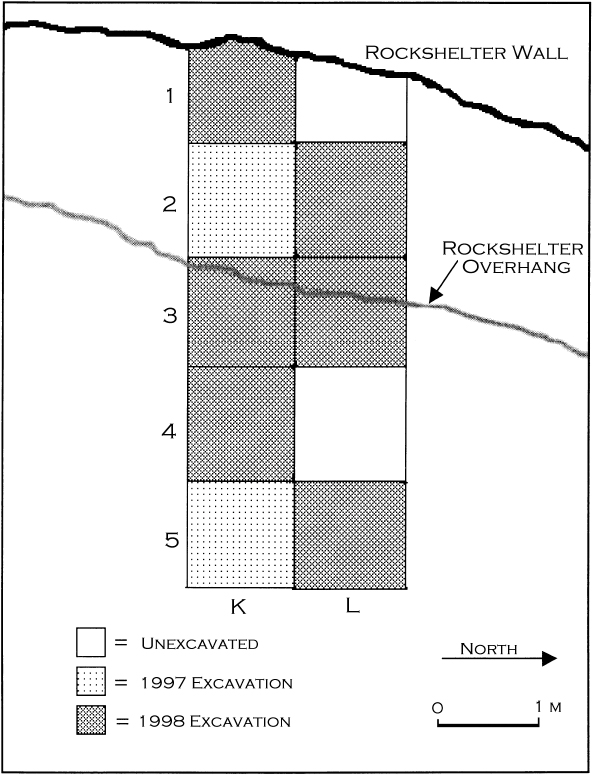

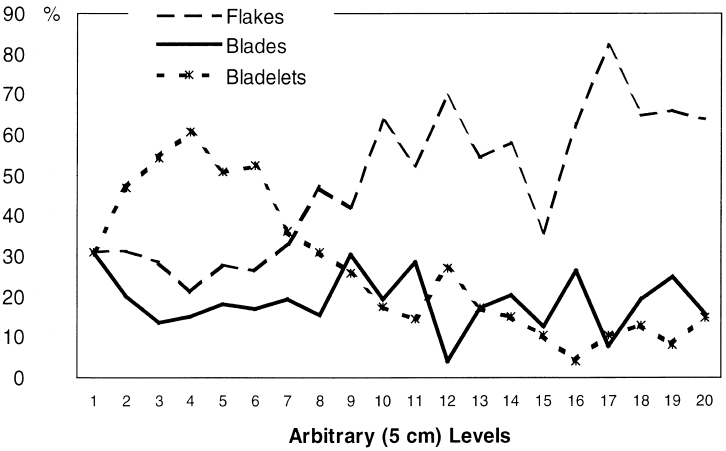

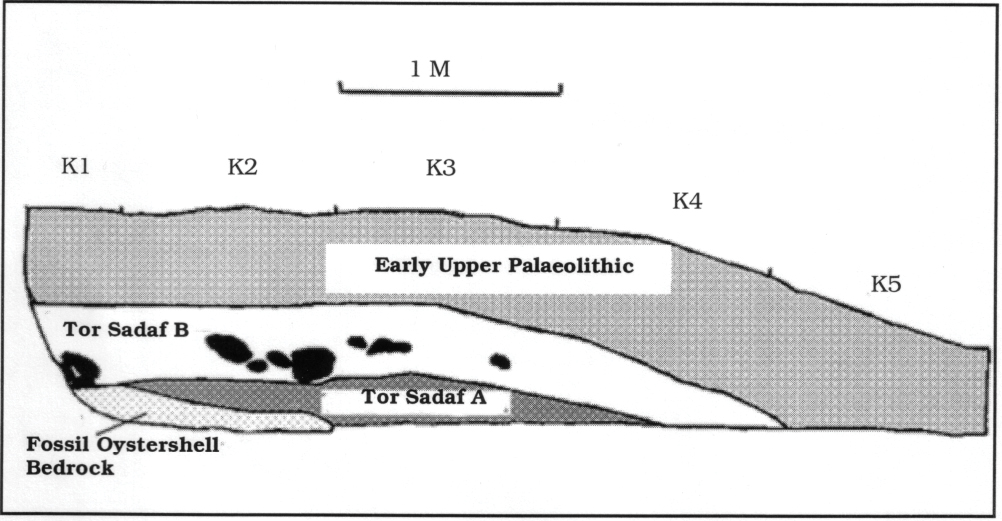

Investigations at Tor Sadaf were conducted over two seasons in 1997–98, as part of the Eastern Hasa Late Pleistocene Project (EHLPP) (Olszewski et al. 1998; Coinman et al. 1999). Excavation of eight 1 m2 units (Fig. 8.1) took place in arbitrary 5 cm levels, and revealed over 1 m depth of in situ deposits, consisting primarily of chipped-stone tools and debitage, and faunal remains. Limestone bedrock was exposed at the base of excavation units located beneath the rockshelter overhang. Sediments are predominantly aeolian and colluvial, and consist of homogeneous fine-grained silty loam. Although some differentiation of ‘natural’ levels was possible, these levels could only be observed in profile walls of the excavation, and appear to represent minor variations in the continuous depositional sequence of the site. The only exception to this continuous sequence of fine-grained sediments was a surface layer (ca. 5 cm depth) of dense dung deposits from modern activity and the presence of a deeper layer (at ca. 1 m depth) of limestone boulders and large cobbles (the ‘cobble-layer’ in Coinman and Fox 2000)(Fig. 8.2).

The cobble-layer was observed only in units below the rockshelter overhang, and did not appear to extend into the open-air portions of the site. The stones making up this layer tend to be angular, relatively unweathered, and occur in association with high artefact densities. Although the distribution of these stones suggests that they may represent roof-fall, the stones do not contain fossilized oystershell remains, indicating that they do not originate from the rockshelter parent material. The stones of the cobble-layer appear to have more in common with some outcrops of limestone found upslope from the site, suggesting that they may have been transported from that location. All of this makes it tempting to interpret the cobble-layer as the remains of a cultural feature, but this suggestion is impossible to prove at this point. It remains possible that the cobble-layer originated from inclusions which fell from the rockshelter roof, although no such inclusions were observed in the parent material. In any case, the high density of artefacts associated with the cobble-layer suggests that if this material represents a period of roof collapse, it must have occurred within a relatively short duration since sedimentation and artefact deposition show no evidence of interruption. Abundant archaeological remains were recovered throughout the vertical sequence at the site and, combined with the sedimentological observations, indicate that the deposits accumulated at a relatively steady pace, without the formation of discrete surfaces or floors.

Fig. 8.1 Plan View of Excavation Units at Tor Sadaf.

Fig. 8.2 Profile of the Tor Sadaf Rockshelter Showing ‘Natural’ Stratigraphy.

Pollen analyses are still pending, but preliminary analysis of faunal remains suggested that they include large amounts of small and medium bodied taxa, including gazelle, tortoise and hare. These data contrast with many of the later Upper Palaeolithic faunal assemblages located closer to the palaeo-lakeshore where large bovid and equid species are more common (see Coinman this volume). Phytolith analyses show relatively high proportions of woody plant stems with low proportions of foliage1. These results combined with the faunal and sedimentological observations, suggest that the occupations at Tor Sadaf occurred during a relatively dry period in the Hasa area, and were also possibly keyed to a late fall or winter seasonal cycle. At this point, Tor Sadaf is the only well-studied Early Upper Palaeolithic site in the Wadi al-Hasa, making attempts at comparison limited to much later occupations, most of which occur within the main lake basin. Efforts at environmental study are also complicated by the lack of radiometrically datable material from Tor Sadaf, so that correlation with the existing chronology of lake activity and changing resource zones in the area is difficult to evaluate.

In general, the sedimentological and stratigraphic observations from the site suggest that the site witnessed a relatively continuous depositional sequence. There is no evidence of stratigraphic breaks or discontinuities in the stratigraphy of the site, suggesting that Tor Sadaf may also offer a glimpse of continuous cultural change over the course of occupation. This proposition is investigated in the analysis section.

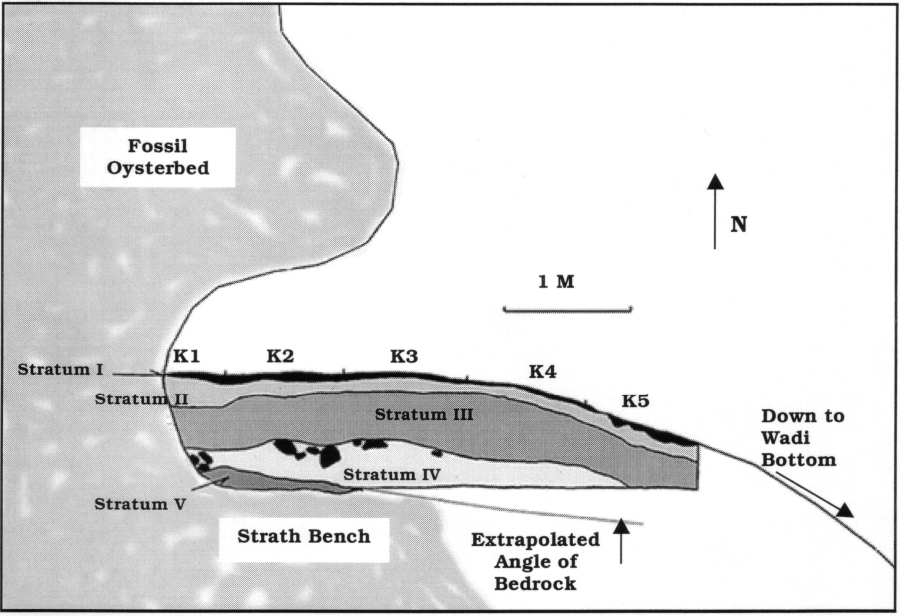

Since the stratigraphy at Tor Sadaf is relatively homogeneous and preliminary analyses (Coinman and Fox 2000) suggested that there was no correspondence between minor changes in sedimentation and changes in lithic technology, analysis proceeded by first dividing the lithic materials according to technological and typological attributes. This approach was more useful than dividing the lithic materials by subtle (indeed, barely detectable in some units) changes in silt/sand/clay proportions, which provide the only means of differentiating most ‘natural’ levels in the site. In addition to the stratigraphic homogeneity of the site sequence, aspects of the lithic artefacts also suggest a continuous sequence of occupation and technological change. Fig. 8.3 shows a plot of artefact density in 5 cm excavation levels in unit K3. It can be seen that, although there are fluctuations in artefact density, there is no indication of a hiatus as artefact densities remain well over 100 per m3x .05 until the very uppermost level. Fig. 8.4 shows frequencies of flakes, blades and bladelets by arbitrary levels in unit K3. Again, although there are fluctuations from level to level, it can be seen that the overall trend is gradual, from a flake/large blade dominated assemblage to a bladelet-dominated assemblage. Similar trends of gradual change at the site have been illustrated elsewhere (Coinman and Fox 2000; Fox 2000).

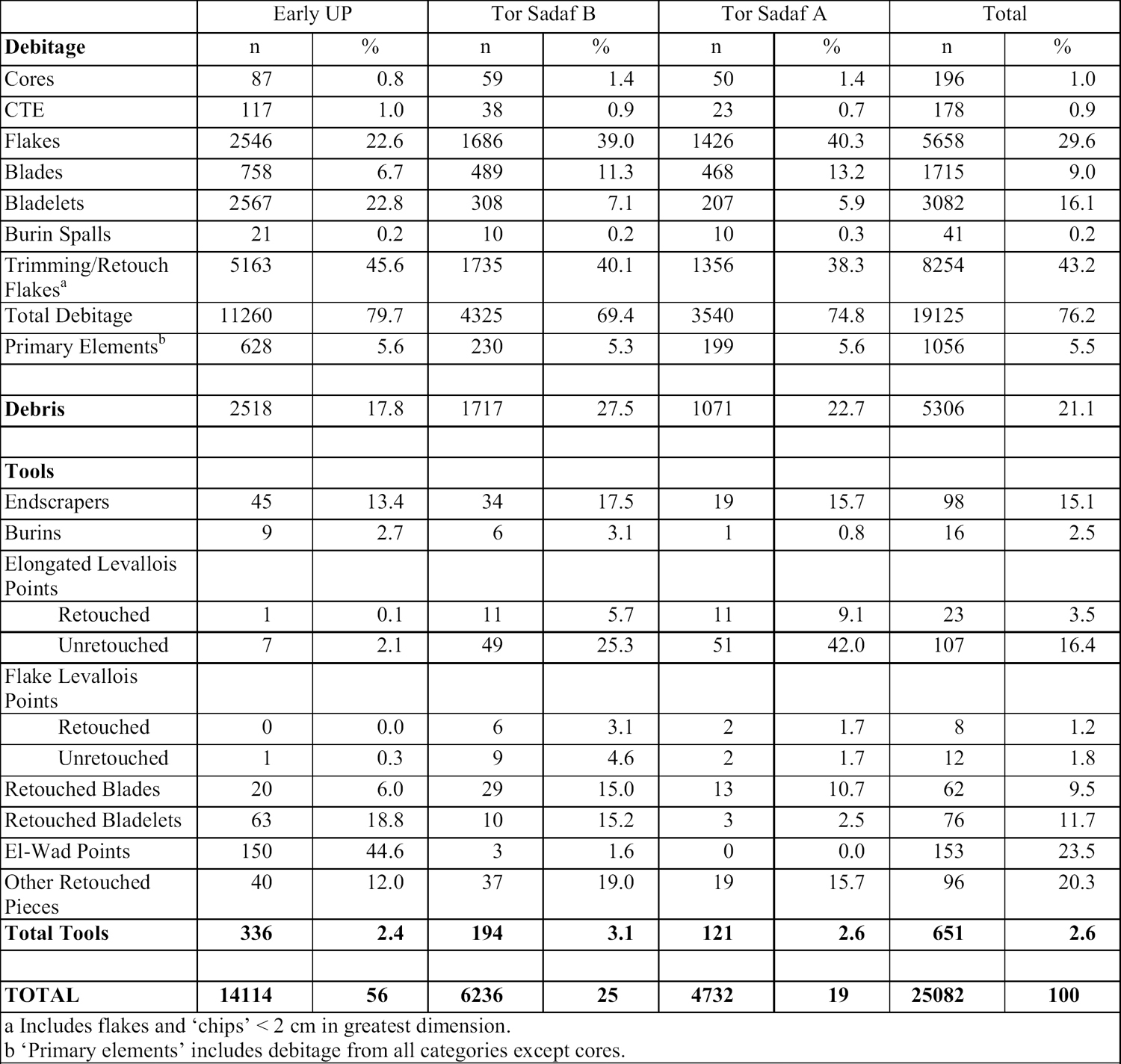

Thus, in order to monitor technological change at the site, the lithic materials were divided into three stratigraphically related analytical units or ‘occupation levels’ on the basis of blank counts and platform attributes of blades. These three occupation levels form the basis of comparison for understanding change in lithic technology, and are designated (from latest to earliest): Early Upper Palaeolithic, Tor Sadaf B and Tor Sadaf A2 (Fig. 8.5). Table 8.1 shows the correspondence between excavation units, arbitrary excavation levels, natural stratigraphy and analytic units (occupation levels). The use of the three analytic units has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Coinman and Fox 2000), so my discussion here will be limited to a few important points.

Given the nature of the undifferentiated sediments and high artefact densities throughout the arbitrary excavation levels and units at Tor Sadaf, I would argue that any temporal division of the lithic materials into discrete units is largely arbitrary. As the subsequent analyses show, the grouping of the materials from more than 20 arbitrary 5 cm levels in eight 1 m2 units into three occupation levels has proved useful for identifying and examining technological and typological changes at Tor Sadaf (Fox 2000). It should be clear that the use of these three occupation levels is not intended to suggest discrete cultural phases. Rather, I have used these three occupation levels as a heuristic device to illustrate important changes in lithic technology over time.

Following initial sorting and counting of all lithic artefacts according to debitage and tool categories, the technological analysis proceeded in a number of steps. First, all cores (n= 196) were analyzed using a number of variables designed to illuminate technological variability and changes in reduction strategies. Following this, samples of blades and flakes were drawn from every arbitrary level and unit excavated at the site. In all, over 1,500 blades and flakes were sampled for detailed metric and attribute analysis, ensuring that all temporal and spatial aspects of the site’s materials were included. Preliminary studies showed that blades were particularly useful for illuminating core reduction strategies, and so these pieces are the primary focus of debitage analysis in this study. Finally, a metric and attribute analysis focusing on retouched and unretouched points was performed, since these pieces represented the overwhelming majority of tools from the three assemblages. This sequence of analyses has provided an abundance of useful data for understanding changes in reduction strategies employed at Tor Sadaf.

Fig. 8.3 Plot of Artefact Densities by Arbitrary Levels in Unit K3 at Tor Sadaf.

Fig. 8.4 Plot of Artefact Percentages by Arbitrary Levels in Unit K3 at Tor Sadaf.

Across the three occupation levels at Tor Sadaf, the production of bladelets becomes increasingly important over time (Table 8.2). The increase in bladelet frequency comes at the cost of both flakes and blades. This trend culminates in the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage, where blades and bladelets comprise nearly 30% of the debitage recovered. The emphasis on blade production in the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage can likely be explained in reference to the abundance of tools on blade/bladelet blanks. Many of these blanks were modified into retouched bladelets and el-Wad points, a strong indicator of the Ahmarian character of the assemblage. In the absence of radiocarbon dates, the assignment of this assemblage to the Early Upper Palaeolithic rests on two major factors. First, the assemblage appears broadly comparable technologically and typologically to Early Ahmarian assemblages in the Levant, including those from Boker A in the Central Negev (Jones et al. 1983), the Lagaman sites of the Sinai (Gilead and Bar-Yosef 1993), Ksar Akil in Lebanon (Bergman 1987a, 1988a) and southern Jordan (Coinman and Henry 1995; Williams 1997a; Kerry 1997a). The Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage from Tor Sadaf also differs from the Late Ahmarian sites found in the Hasa area, such as Ain al-Buhayra and Yutil al-Hasa. These later sites have been dated to the interval of ca. 19–23,000 bp, and contain lithic assemblages with very small bladelets and retouched Ouchtata points (Coinman 2000). The Tor Sadaf Early Upper Palaeolithic materials also contrast with materials recovered from the recently discovered lakeshore site of Thalab al-Buhayra, dated to ca. 26,000 bp and only described preliminarily at this point (Coinman 2000:146–149).

Table 8.1 Correspondence Between Natural and Arbitrary Levels in Excavation Units and Analytic Units (Occupation Levels) Used in the Analysis.

| Stratigraphic Unit | Arbitrary Level by Excavation Units | Occupation Level |

| I, II, III (upper portion) | K1 (1–7), K2 (1–8), K3 (1–9), K4 (1–10), K5 (1–11), L2 (1–7), L3 (1–7), L5 (1–13) | Early Upper Palaeolithic |

| III (lower portion) | K1 (8–14), K2 (9–16), K3 (10–15), K4 (11–17), L2 (8–13), L3 (8–15) | Tor Sadaf B |

| IV | K1 (15–18), K2 (17–20), K3 (16–20), K4 (18), L2 (14–17), L3 (16–20) | Tor Sadaf A |

| V Sterile Oystershell Bedroek (Strath Bench) | ||

| Note: Bold numbers indicate the lowest arbitrary level excavated. | ||

Table 8.2 Frequencies and Percentages of Lithic Artefacts by Occupation Periods from Tor Sadaf.

Fig. 8.5 Profile of the ‘K’ Trench at Tor Sadaf Showing Analytical Units (Occupational Levels) Discussed in the Text.

Perhaps most importantly, the Tor Sadaf Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage appears to be stratigraphically continuous with the earlier Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages, which appear to conform broadly with the technology seen at the transitional sites of Boker Tachtit and Ksar Akil (Marks 1983c; Marks and Kaufman 1983; Bergman 1987a; Ohnuma and Bergman 1990). Although a lack of radiometrically datable material from Tor Sadaf prevents definitively demonstrating the continuity between the Early Ahmarian and the earlier Tor Sadaf A and B, the stratigraphic and technological continuity at the site support this hypothesis.

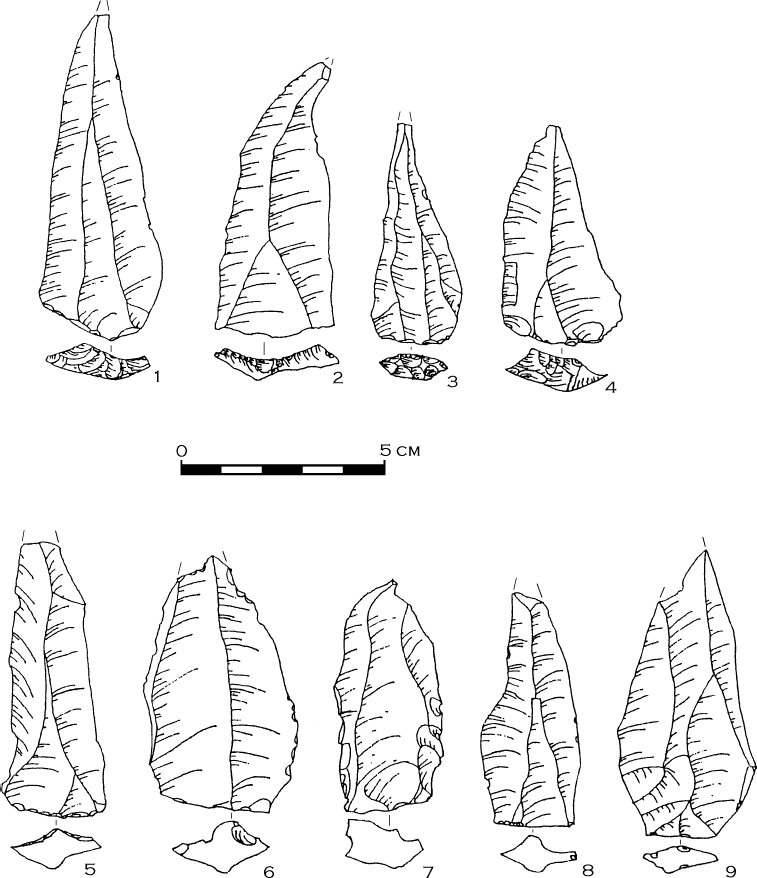

In the Tor Sadaf A and B occupation levels, reduction appears primarily geared toward the production of large triangular points with blade-like proportions. I have categorized these points as ‘Levallois,’ on the basis of their morphological characteristics despite the fact that they often appear to have been produced by methods other than ‘true’ Levallois (discussion of this classification problem can be found in Marks 1983c and Volkman 1983). Following other workers in the Levant (e.g., Marks and Kaufman 1983), I have included all Levallois points in the tool counts, whether retouched or not. Retouched blades also represent an important category of tools during these early occupations, suggesting that the production of blades may not have been purely incidental to the point production process. At Boker Tachtit, Volkman (1983) documented reduction strategies that produced both blades and Levallois-like points from a single reduction sequence. In general, Tor Sadaf A and B appear to document similar reduction strategies, and bear striking similarity to those assemblages described as ‘transitional’ or ‘Initial Upper Palaeolithic’ (Marks 1983c, 1993; Ohnuma and Bergman 1990). Below, each of the three occupation levels defined at the site is explored in terms of core and core trimming element samples, blade and bladelet debitage, and toolkits. Each of these categories of evidence is then summarized to elucidate changes in lithic core reduction strategies evidenced in the three assemblages.

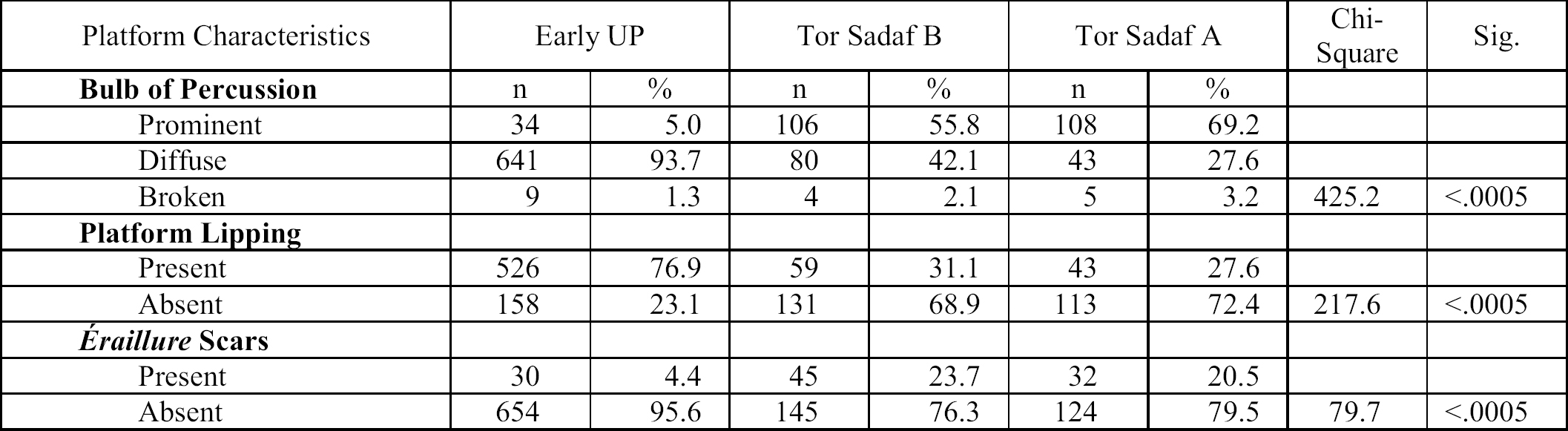

Analyses of cores and core trimming elements provide an important line of evidence for changes in core reduction strategies. The great majority of cores from all three occupation levels are unidirectional, single platform types (Figs. 8.6–7). Cores that have more than one platform are in most cases those that have been reoriented; rarely is more than one platform involved in a single reduction sequence. There are, however, important changes in cores over time at the site. Cores from the Tor Sadaf A and B are predominately point cores, and are comparable to those seen at Boker Tachtit (Marks and Kaufman 1983). In the earliest levels (Tor Sadaf A), many of these cores show faceting as a means of platform preparation (Table 8.3). This characteristic fades over time, with a shift to simple, unfaceted platforms in the Tor Sadaf B levels. In both Tor Sadaf A and B, the type of platform faceting on cores varies considerably. Faceting is at times of a fairly formal sort, producing convex platforms common in Levallois assemblages, but is often also of an apparently ad hoc informal sort. Nearly all the Early Upper Palaeolithic cores have unfaceted platforms, as expected in an assemblage dominated by a true blade technology. This shift to unfaceted platforms is correlated with other changes in reduction strategies discussed below.

Fig. 8.6 Faceted Single Platform Elongated Point Cores from Tor Sadaf A (2) and B (1).

Fig. 8.7 Single Platform Blade/let Cores from the Tor Sadaf Early Upper Palaeolithic.

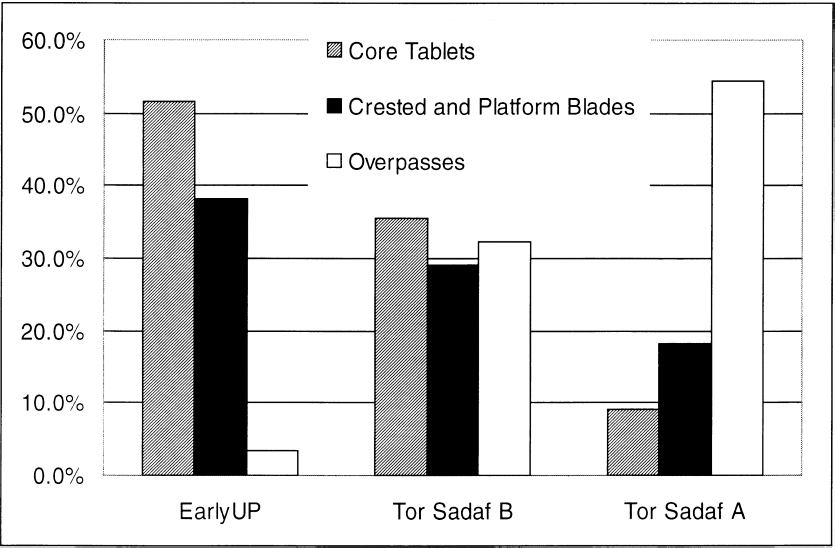

Core trimming elements represent 0.7–1.0% of the debitage from each of the three occupation periods. These pieces are sorted into three general types, and illustrate shifts in core reduction strategy over time (Fig. 8.8). The use of crested and unifacial platform blades becomes more common over time at Tor Sadaf, culminating in the blade technology of the Early Upper Palaeolithic. The use of the core tablet technique, though present in all three occupation levels, is quite rare in the Tor Sadaf A assemblage, becoming more prominent in the subsequent Tor Sadaf B and the dominant type of core trimming element in the Early Upper Palaeolithic.

Table 8.3 Frequencies and Percentages of Cores with Unfaceted, Dihedral and Muti-Faceted Platforms by Occupation Level from Tor Sadaf.

Table 8.4 Metric Attributes of Complete Blade/lets by Occupation Level from Tor Sadaf.

Overpassed pieces represent a third important category of core trimming element, and show continuous decline across the three occupation levels. Most of these pieces have blade proportions, and typically originate on an unfaceted platform. These overpassed core trimming elements remove portions of the distal end of the core, generating a pyramidal core shape. Occasionally, these pieces originate from the distal end of the core, but accomplish a similar result. Overpassed core trimming elements that originate on the distal end of the core typically remove significant portions of both the distal and proximal ends of the core as well as most of the core face. At Tor Sadaf, many of these overpassed pieces preserve aspects of the lateral portions of core faces, suggesting that these core trimming elements may have simultaneously served to reshape the lateral aspects of the core. Reshaping of lateral core faces is a necassary feature of unipolar, convergent reduction strategies that produce large numbers of Levallois-type products (Hovers 1998:149–150).

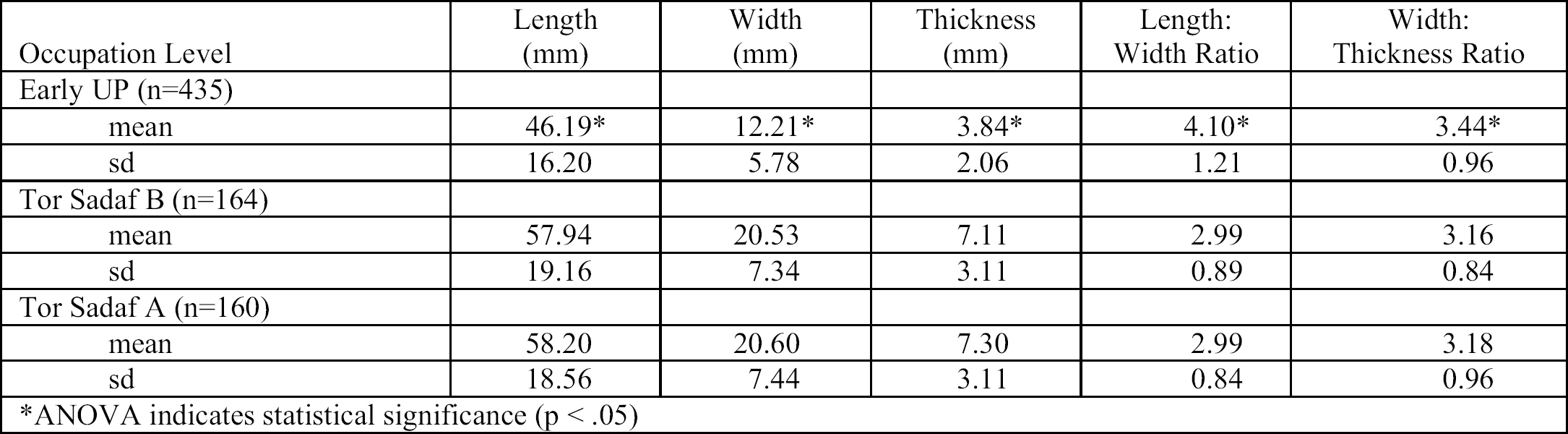

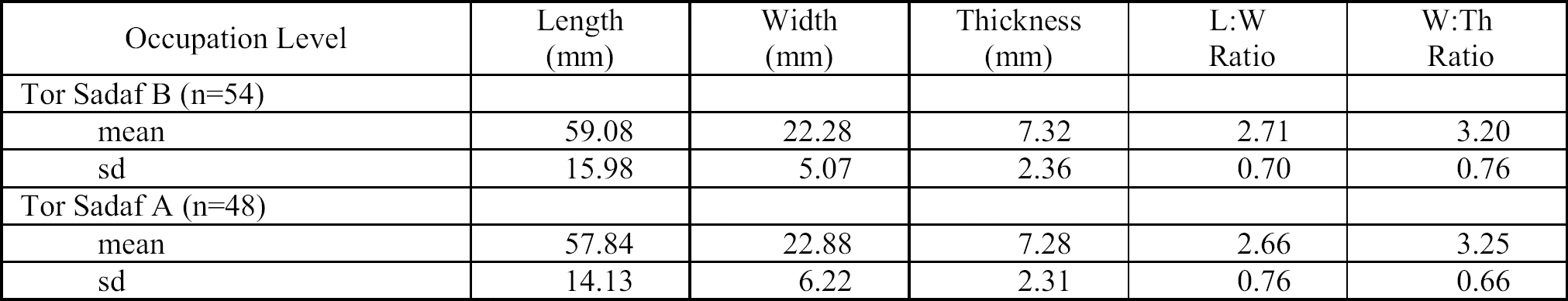

Table 8.2 shows that while blade production was important in all three occupation levels at Tor Sadaf, production shifted toward smaller blank forms during the Early Upper Palaeolithic. Metric data from blades and bladelets are shown in Table 8.4, where it can be seen that the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage appears distinct from the earlier assemblages in every attribute, and these differences are highly significant statistically. In overall shape, blade debitage from the Tor Sadaf A and B periods appear very similar, and ANOVA tests suggest no significant differences. These results contrast with those seen for platform metrics in Table 8.5, where all three assemblages show distinct differences, which are highly significant statistically. These results illustrate that, although there is a shift in reduction strategy and platform preparation, blank production is remarkably stable in terms of overall metrics from the Tor Sadaf A to B assemblages. The Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage stands separate from the earlier ones both in terms of overall blank and platform metrics.

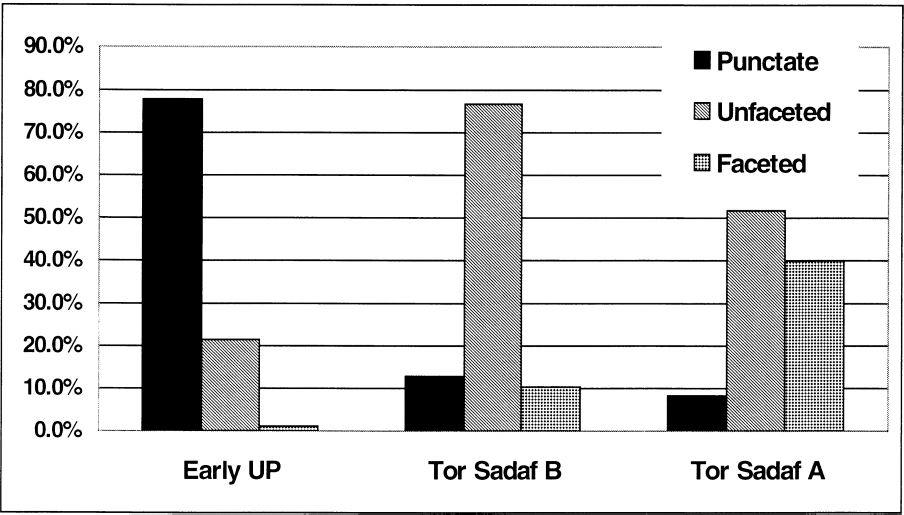

Differences in the metric attributes of blades and bladelets in the three assemblages are also correlated with a number of distinct platform attributes (Fig. 8.9). In this analysis, punctiform platforms were defined as small (less than 5 mm in largest dimension) linear platforms, with abraded dorsal aspects, which contrast strongly with the large, unfaceted platforms common on many blades. The Tor Sadaf A assemblage is associated with a balance of large, faceted and unfaceted platforms. The Tor Sadaf B is associated almost entirely with large unfaceted platforms, and gives way to the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage, where the overwhelming majority of blades and bladelets have extremely small, punctiform platforms.

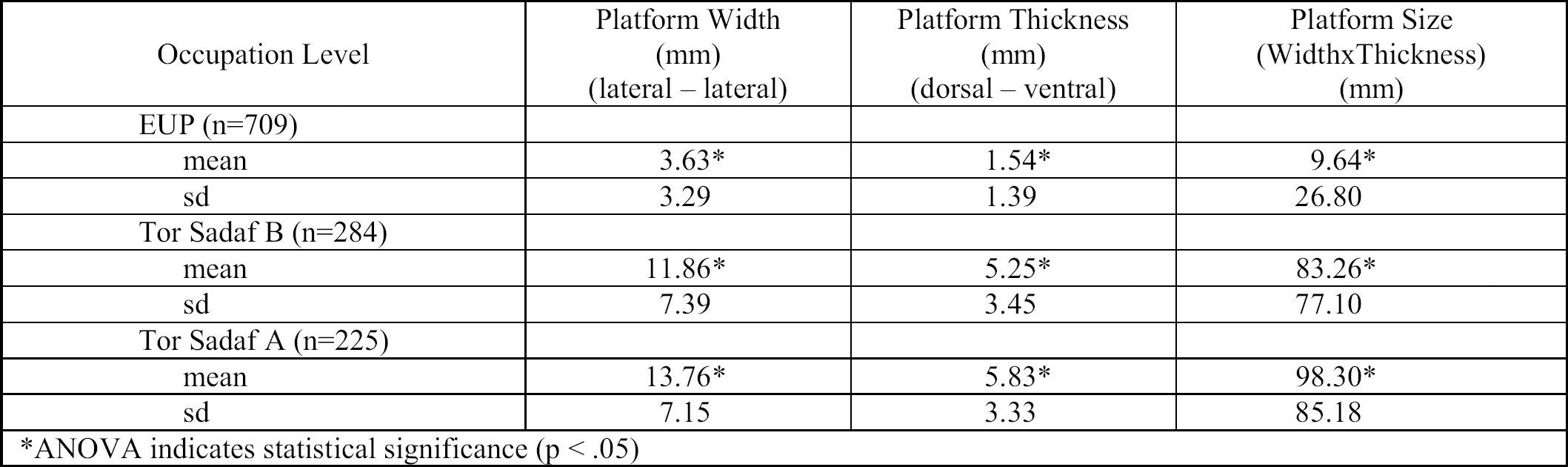

A final set of platform attributes can be used to understand shifts in blade production over time (Table 8.6). Although it is known that platform lipping, éraillure scarring and prominent percussion bulbs can be produced using any mode of flaking, the frequency of these attributes in large numbers of artefacts is strongly suggestive of hard hammer versus soft hammer and indirect percussion modes. The increased frequency over time of diffused bulbs of percussion and lipped platforms combined with the decreased frequency of éraillure scars suggests a long-term shift in blade production techniques from direct hard hammer percussion to soft hammer and indirect percussion modes of flaking. Chi-square tests indicate that differences in the frequencies of these attributes are highly significant between the three occupation levels. This trend is consistent with the notion of the emergence of true blade technology commonly associated with the Upper Palaeolithic.

Fig. 8.8 Percentages of CTE by Occupation Level at Tor Sadaf.

Fig. 8.9 Percentages of Blade/lets with Punctate Unfaceted and Faceted Platforms by Occupation Level at Tor Sadaf.

Table 8.5 Metric Attributes of Blade/let Platforms by Occupation Level from Tor Sadaf.

Table 8.6 Frequencies and Percentages of Blade/lets with Platform Characteristics by Occupation Level at Tor Sadaf with Chi-Square Test Statistics.

The tool assemblages from Tor Sadaf are dominated by point forms throughout all three levels. Burins increase in frequency slightly over time, but in general, remain quite unimportant in all three occupation levels. Endscrapers, in contrast, are a consistently important tool form throughout the three periods. Retouched blades are more abundant in Tor Sadaf B than in the earlier Tor Sadaf A, but are replaced almost entirely by retouched bladelets during the Early Upper Palaeolithic. The most abundant tool forms by far in all three assemblages are points, especially those on blanks of blade/bladelet proportions. With the exception of the elongated Levallois points, all three toolkits appear typologically Upper Palaeolithic in character. Sidescrapers, notches and denticulates are all rare throughout the sequence.

For the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages, points are mostly of the elongated Levallois type (Fig. 8.10), and appear similar to those documented in other transitional contexts (Marks and Kaufman 1983) and some Middle Palaeolithic contexts as well, particularly those of Tabun D type (e.g., Lindly and Clark 1987). In this analysis, these points were defined as triangular pieces with converging lateral margins, and included both retouched and unretouched pieces. Dorsal scar patterns suggest that nearly all of these points were produced on unidirectional, single platform cores (Fox 2000). Metric attributes of the Levallois points show that in overall metrics, those from the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages are virtually indistinguishable (Table 8.7) and generally are remarkably similar in size to the blade debitage discussed earlier for Tor Sadaf A and B (Table 8.4).

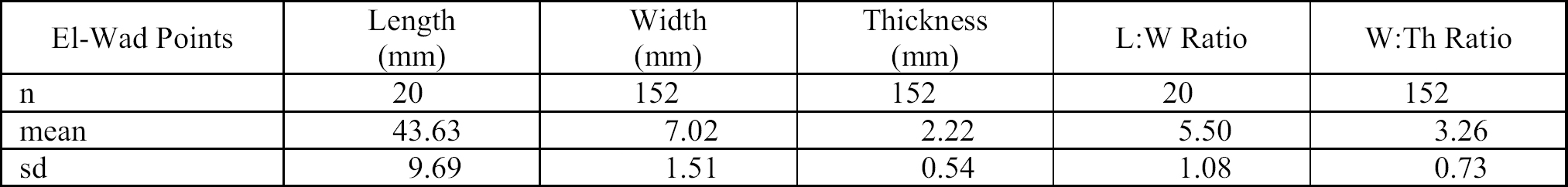

The abundance of el-Wad points in the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage is an important indicator of the well-known Early Ahmarian entity in the Levant. At Tor Sadaf, these points are typically produced on relatively large bladelets and small blades, and are commonly characterized by right proximal obverse and inverse retouch, and distal right and left obverse retouch (Fig. 8.11). These points are in fact highly variable in retouch attributes, but appear relatively distinct in metric attributes, as shown by the very small standard deviations in Table 8.8. At Tor Sadaf, el-Wad points are invariably associated with punctiform platforms, showing lipping, diffuse bulbs of percussion and abraded platform edges.

Fig. 8.10 Elongated Levallois Points from Tor Sadaf: a-d, Points with Faceted Platforms from Tor Sadaf A; e-i, Points with Unfaceted Platforms from Tor Sadaf B.

The analysis presented here illustrates a sequence of changing core reduction strategies at Tor Sadaf. The earliest occupation level at the site, represented by the Tor Sadaf A assemblage, is characterized by a singleplatform core reduction strategy focused on the production of elongated Levallois-like points using a reduction strategy not typically Levallois in nature. Blanks were struck from cores with roughly equal proportions of either faceted or unfaceted platforms using hard hammer percussion. These point cores were shaped and maintained by the removal of unifacial platform blades and large, overpassed pieces. The latter were used to trim the distal aspects of cores (generating a pyrammidal shape). Although the core tablet technique is evident, it appears to have been applied relatively rarely. Instead, platforms were commonly shaped and maintained through removal of small flakes, creating many faceted platforms on cores, debitage and points. The reduction process also produced a significant number of blades, many of which were retouched and represent a substantial portion of the toolkit in the assemblage.

The Tor Sadaf B assemblage is typologically indiscernible from, and technologically similar to, the Tor Sadaf A assemblage. But some important technological differences should be noted. Cores continue to be oriented unidirectionally, and large elongated points continue to be a major objective of reduction. Use of overpassed pieces as a means of shaping cores continues to be important, but core preparation and maintenance appear to be more variable than before. The use of unfaceted platforms predominates, and evidence of this change is preserved in platforms of cores, blades and points. In Tor Sadaf B the core tablet technique appears to be an important means of maintaining platform regularity and angle, replacing the platform faceting seen earlier in the Tor Sadaf A assemblage. Hard hammer percussion continues to be the dominant mode of flaking, though platform attributes suggest an increasing frequency of soft hammer and indirect flaking modes. Given these technological differences between the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages, it is striking that the debitage and tools from the two assemblages should appear so uniform in metric and typological attributes. This is a clear example of a shift in technology that is not reflected in tool or debitage typology. This decoupling of lithic technology and typology in assemblages of a transitional nature was noted by Marks (1983c).

Fig. 8.11 El-Wad Points from the Early Upper Palaeolithic Tor Sadaf Assemblage.

The Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage from Tor Sadaf is characterized by both a technological and a typological shift from the previous levels. The assemblage shows a marked increase in blade and bladelet production, which is related to the emergence of a true blade technology, where uniform series of blades and bladelets are removed from core faces using soft hammer and indirect percussion. Cores continue to be overwhelmingly unidirectional and single platform. The growing number (compared to previous occupation levels) of bifacial crested blades and the predominance of the core tablet technique are also strong indicators of a truly Upper Palaeolithic blade technology appearing at this time. Typically Early Ahmarian artefacts, especially retouched blades and bladelets and el-Wad points, dominate the toolkit.

The Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage from Tor Sadaf exhibits the most diagnostic traits of the three assemblages, and can be clearly added to the large number of Ahmarian manifestations known throughout the Levant. First defined in the 1980s (Gilead 1981a; Marks 1981b), the Ahmarian is increasingly being differentiated into early and late phases (Bergman and Goring-Morris 1987; Coinman 1997b; Ferring 1988; Williams 1997a), with el-Wad points typically associated with the early part of the sequence. The Tor Sadaf Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage fits nicely into the Early Ahmarian classification, given its high proportions of el-Wad points, unidirectional core reduction strategy, use of a true blade technology and the fact that it overlies an assemblage clearly associated with an earlier technological phase. This classification would be strengthened considerably by radiocarbon dating of the Early Upper Palaeolithic materials, but in the absence of datable remains only technological analyses are available. If it is accepted, as I have argued here, that the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage from the site represents the Early Ahmarian and that the Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage appears stratigraphically continuous with the Tor Sadaf A and B occupation levels, then the date from the site of Boker A (Jones et al. 1983) would suggest that the Early Upper Palaeolithic at Tor Sadaf might begin as early as 37–38,000 bp.

Table 8.7 Metric Attributes of Levallois-like Points from the Tor Sadaf Transitional A and B Assemblages.

Table 8.8 Metric Attributes of el-Wad Points from the Tor Sadaf Early UP Assemblage.

Classification of the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages and placing them into the broader chronological context of the Levant is somewhat more problematic. Transitional assemblages are only known from a small handful of contexts in the Levant, providing a limited knowledge of the variability associated with the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition. The Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages appear to most closely resemble assemblages in the Levant classified as either transitional between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic (Azoury 1986) or initial Upper Palaeolithic (Marks and Ferring 1988, Kuhn et al. 1999). All such assemblages also resemble, at least in some superficial sense, the Middle Palaeolithic entity known as Tabun D (Jelinek 1981a, b). Tabun D-type assemblages have been associated with dates from the very early parts of the Levantine Mousterian, however, so these assemblages are not helpful in estimating the age of transitional assemblages such as those from Tor Sadaf. In short, only the site of Boker Tachtit offers any guidance in indicating the approximate timing of the Tor Sadaf A and B occupation levels. If it is accepted that the Tor Sadaf A and B represent a technological bridge between the Boker Tachtit level 4 assemblage and the subsequent Early Ahmarian (as seen at Boker A and in the Tor Sadaf Early Upper Palaeolithic assemblage), then an estimate of between perhaps 43–38,000 bp can be tentatively suggested.

In this paper, I have generally regarded the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages as ‘transitional’ between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic. I have used this term in favor of other designations that are available, for example ‘Emiran’ (Bar-Yosef 1998a) or initial Upper Palaeolithic (Marks and Ferring 1988). Recently, it has been suggested that the use of the term ‘transitional’ may be misguided, since it implies a ‘direct phylogenetic relationship’ between lithic industries of the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic (Kuhn et al. 1999). It would be beyond the scope of this paper to explore the implications of various means of classifying these assemblages. For the purposes of the above discussion, I have sought to demonstrate that the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages appear to be truly transitional in at least one sense; they represent a technological bridge between an earlier phase similar to that documented by Marks (1983c) at Boker Tachtit, and the subsequent Early Ahmarian found throughout the Levant. In this way, the evidence from Tor Sadaf appears to support the proposition put forth by Marks (1983c) nearly twenty years ago, that the Early Upper Palaeolithic (specifically the Early Ahmarian as seen at Boker A) is a direct development of earlier lithic industries seen at Boker Tachtit, Ksar Akil and now, at Tor Sadaf.

The lithic assemblages from Tor Sadaf provide an important new database for understanding the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition and the earliest Upper Palaeolithic in the Levant. The assemblages document a clear shift in lithic technology, beginning with a single platform technology focused on the production of numerous elongated Levallois points, to one increasingly dominated by a true blade technology. In the absence of radiometric dates from the site, it is difficult to say with certainty how the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages fit into the regional chronology of the Levant. It seems clear that these assemblages are related to so-called ‘transitional’ and ‘Initial Upper Palaeolithic’ assemblages from other sites in Israel and Lebanon (Marks 1983c; Ohnuma and Bergman 1990). Future research, and especially radiocarbon dates, should provide the ability to further evaluate the propositions put forth here. First, absolute dates would solidify the argument made here, that the vertical sequence at the site represents a technological continuum from a transitional assemblage to a true Upper Palaeolithic one. Second, datable materials would resolve the question of whether the transitional materials from the Tor Sadaf A and B assemblages represent occupations contemporaneous with those from Boker Tachtit (suggesting regional variability), or if they in fact date to a later phase intermediate between the Boker Tachtit level 4 assemblage and the subsequent Early Ahmarian. Should, however, such datable materials not be forthcoming, interpretation of the Tor Sadaf materials and their implications for the Levant in general must rely on further technological and palaeoenvironmental data.

The Eastern Hasa Late Pleistocene Project (EHLPP), under the direction of D.I. Olszewski and N.R. Coinman, has been funded by the National Science Foundation (SBR9618766), the Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (Grant #6278), the National Geographic Society (Grant #6695-00), the United States Information Agency, the American Centers for Oriental Research and the Joukowsky Family Foundation. Financial and logistic support for my research has been provided by the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate College at Iowa State University. Artefact illustrations are the work of Antena Brynne (Iowa State University). I would like to thank Nigel Goring-Morris and Anna Belfer-Cohen for inviting me to contribute this paper. Nancy Coinman, Nigel Goring-Morris and Anna Belfer-Cohen provided editorial comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and an anonymous reviewer provided very useful criticism. I am grateful to these individuals for improving the clarity and content of this paper; any shortcomings remain my responsibility. This is EHLPP contribution #19.

1 The phytolith analyses were conducted by Arlene Miller Rosen, Institute of Archaeology, University College of London.

2 In a previous preliminary report (Coinman and Fox 2000), Tor Sadaf A and B were referred to as Transitional A and B.