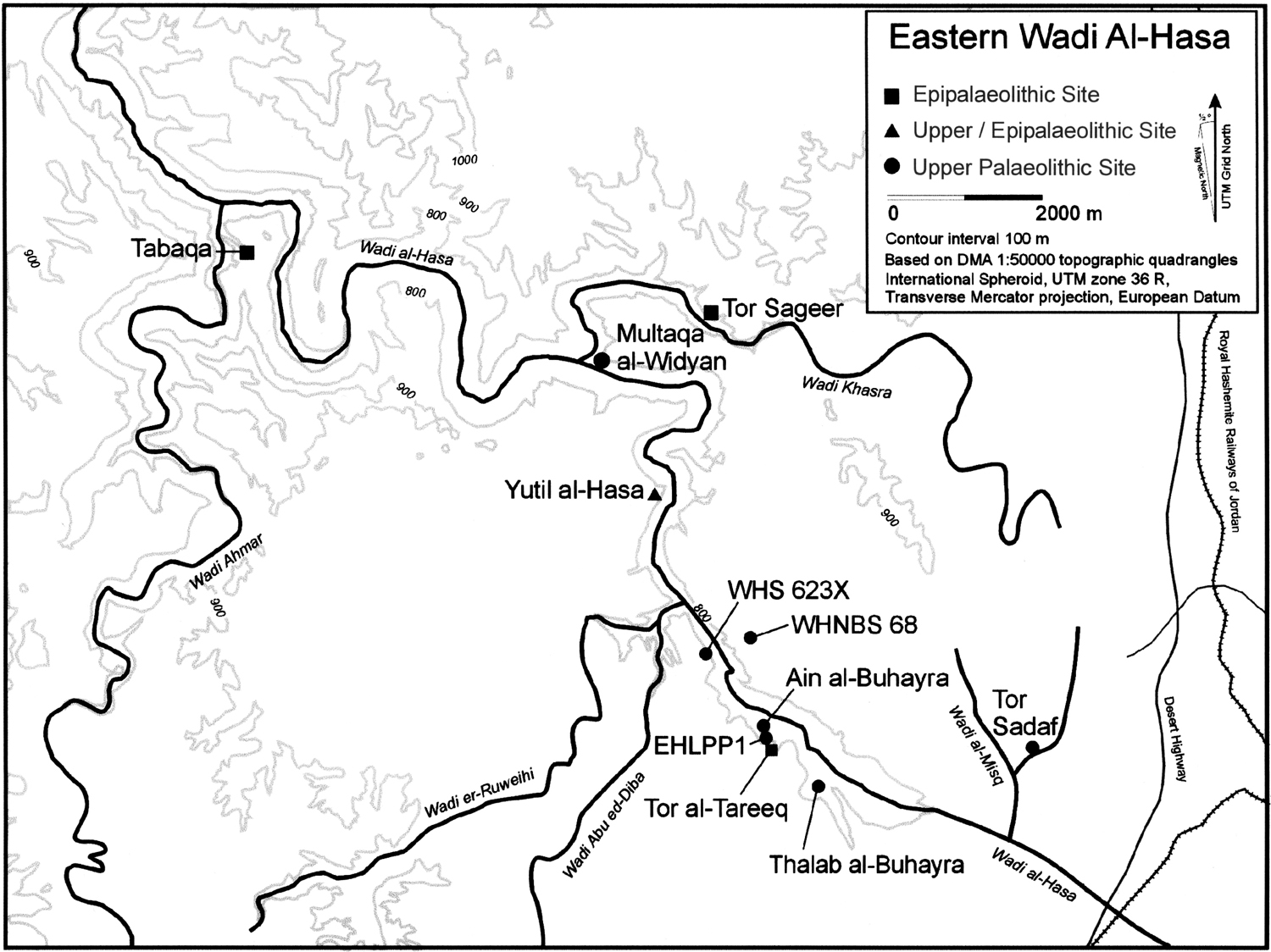

Fig. 13.1 Map of the eastern end of Wadi al-Hasa, showing the locations of Upper Palaeolithic sites discussed in text.

For the last 20 years, most discussions about the Levantine Upper Palaeolithic have focused on a dichotomy in material culture – the Levantine Aurignacian and the Ahmarian (Gilead 1981a; Marks 1981a). Although researchers continue to debate the appropriate criteria to define, describe, and distinguish the Levantine Aurignacian technocomplex, there is a somewhat greater consensus on what is represented by Ahmarian technology and typology. A growing database of Ahmarian sites now includes southern and eastern Jordan. Archaeological research in the al-Hasa area of eastern Jordan since the early 1980’s documents an extended chronology of Upper Palaeolithic sites in the eastern basin (Fig. 13.1) which all exhibit a clear association with the Ahmarian. This paper presents evidence for the emergence and evolution of the Ahmarian at a series of sites in which the lithic assemblages illustrate technological and typological trends over a time span of some 20,000 years. It includes a Late Ahmarian that extends at least to ca. 19,000 bp, overlapping with the Early Epipalaeolithic in the al-Hasa basin (Olszewski herein) and the Masraqan, a recently defined Early Epipalaeolithic socio-cultural entity (Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 1997). This research adds to a growing database of Ahmarian sites and identifies additional aspects of assemblage variability that characterize the Ahmarian.

Since the early 1980’s considerable efforts have been directed at defining and distinguishing two Upper Palaeolithic traditions or technocomplexes based on technological and typological characteristics, and to some extent, temporal and geographic distributions. The Levantine Aurignacian is thought to exhibit strong similarities to the European Aurignacian, featuring typical Upper Palaeolithic tools, such as endscrapers and burins, especially ‘Aurignacian,’ carinated, and nosed varieties, as well as bone and horn core tools (Neuville 1934; Garrod 1953; Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef 1981; Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1988; Belfer-Cohen 1994; Gilead 1991). Core reduction was focused predominantly on flake debitage and tool blanks with low proportions of blades and bladelets. Lithic assemblages from some sites in the Negev, such as Ein Aqev (Marks 1976b), Sde Divshon (Ferring 1976), and Arkov (Larson and Marks 1977) have been identified as having Aurignacian elements, exhibiting a relatively inferior blade technology as seen in large, thick blades and the lack of a true bladelet technology (Marks and Ferring 1988:46, 64–65; Gilead 1991:128). However, some question the applicability and relevance of the Levantine Aurignacian to all flake-based assemblages, particularly those outside the core Mediterranean area (e.g., Bergman and Goring-Morris 1987; Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef 1981; Belfer-Cohen and Goring-Morris 1986), emphasizing the original definition of the Levantine Aurignacian (Belfer-Cohen 1994:247). The Ahmarian, in contrast, is currently recognized as a well-developed blade technology that is dominated by the production of blades and small bladelet tools, many of which are retouched, backed, or pointed (Gilead 1981a, 1989, 1991; Marks 1981a, Marks and Ferring 1988). Traditional Upper Palaeolithic tools, such as endscrapers and burins, occur less frequently.

The Levantine Aurignacian has been found in caves and rockshelters in Lebanon, Syria, and Israel at such sites as Ksar Akil (Copeland 1975; Tixier and Inizan 1981; Bergman 1987a, 1988a, b; Bergman and Goring-Morris 1987; Ohnuma and Bergman 1990), Erq el-Ahmar B (Neuville 1951), el-Quseir C (Perrot 1955), el-Wad C (Garrod and Bate 1937), Kebara D (Garrod 1954; Ronen 1976; Ziffer 1978), Hayonim D (Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef 1981; Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1988), and at Sefunim (Ronen 1976, 1984). Fazael IX in the lower Jordan Valley (Goring-Morris 1980b) and Nahal Ein Gev I (Bar-Yosef 1973) in the northern Jordan Valley are also designated as Levantine Aurignacian sites (Kaufman 1987). Edwards et al. (1988) identified Upper Palaeolithic sites in the Wadi Hammeh (WH 32 and WH 34) as Levantine Aurignacian, while other sites in the lower Jordan Valley have been attributed to the Levantine Aurignacian by Muheisen (1988). The Levantine Aurignacian is also present in the southern Levant at a number of sites in the Negev (e.g., Ein Aqev, Sde Divshon, Arkov) (Marks 1976b; Marks and Ferring 1976; Larson and Marks 1977; Marks and Ferring 1988) and in Sinai (Baruch and Bar-Yosef 1986). In southern Jordan, the sites of Tor Aeid (J432) and Jebel Humeima (J412) were identified initially as Levantine Aurignacian (Henry 1986; Coinman and Henry 1995), but more recently these have been reassessed as Ahmarian sites (Coinman 1998a; Kerry 1997a, 2000; Williams 1997a, b).

Fig. 13.1 Map of the eastern end of Wadi al-Hasa, showing the locations of Upper Palaeolithic sites discussed in text.

The Ahmarian, as currently understood, is known from sites throughout the Sinai at Gebel Maghara (Bar-Yosef and Belfer 1977; Gisis and Gilead 1977; Gilead 1977; Goring-Morris 1987), Qadesh Barnea (Gilead and Bar-Yosef 1993), and Wadi Feiran (Phillips 1988; Gladfelter 1990,1997). Ahmarian sites are well documented in the central Negev (Jones et al. 1983; Ferring 1977) and western Negev (Goring-Morris 1987), the Judean Desert (Neuville 1951; Perrot 1955), as well as in cave and rockshelter sites in the core Mediterranean zone (Ronen and Vandermeersch 1972; Ronen 1976, 1984; Goring-Morris 1980b), and as far north as Lebanon (Ohnuma and Bergman 1990) and southern Turkey (Kuhn et al. 1999). Ahmarian sites have been identified in southern Jordan (Kerry 1997, Williams 1997a, b) and in the Wadi al-Hasa of west-central Jordan (Coinman 1993b, 1997a, b; 1998a, b; 2000; Coinman and Fox 2000; Fox and Coinman 2000; Fox herein; Olszewski 1997; Olszewski et al. 1990, 1994). The Ahmarian has also been documented at a number of sites in the Petra area (Schyle and Uerpmann 1988; Schyle and Gebel 1997), and it also may be present at sites in the Azraq basin (Garrard et al. 1988b, 1994; Byrd 1988; Coinman 1998a, 2000).

Issues concerning the contemporaneity and potential evolutionary relationship between the Levantine Aurignacian and the Ahmarian technocomplexes have been central to discussions of the Levantine Upper Palaeolithic. Some researchers have interpreted the superposition of Levantine Aurignacian assemblages over earlier Ahmarian assemblages to represent a developmental succession from earlier Ahmarian blade-based technology into a flake technology in the later Levantine Aurignacian (Copeland 1986; Bergman and Goring-Morris 1987; Goring-Morris 1987) or as an ‘evolved’ Levantine Aurignacian (Marks and Ferring 1988:64–65). Others have argued that there is minimally a temporal overlap between ca. 29–20,000 bp between the two (Marks and Ferring 1988:68), or that they are partially contemporaneous until ca. 26,000 bp (Phillips 1994:170).

Currently, there are more radiometric dates for Ahmarian assemblages and sites dating between 43–26,000 bp (Bar-Yosef et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1983; Marks and Ferring 1988; Phillips 1988, 1994), but Late Ahmarian sites dating to the time range between ca. 26–20,000 bp or later are limited and restricted to the southern and eastern regions of the Levant. Phillips (1994:170) has questioned the existence of the Late Ahmarian in Jordan and the Negev, arguing that the [Early] Ahmarian existed for only about 12,000 years and was then replaced by the Levantine Aurignacian ca. 26,000 bp. Indeed, the Late Ahmarian, as the terminal Upper Palaeolithic (Goring-Morris 1987, 1995b), has been re-classified as the Masraqan, representing the Early Epipalaeolithic (Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 1997). The Masraqan is dated between ca. 20–15,000 bp and includes sites that are identified by others as late Upper Palaeolithic Ahmarian, e.g., Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) in the Wadi al-Hasa (Coinman 1990, 1993, 1997a, b; 1998a, b; 2000) and Ein Aqev East in the Negev (Ferring 1977, 1980, 1988; Marks and Ferring 1988; Coinman 1990, 1993), as well as other sites, e.g., Ohalo II, Fazael X, Azariq XIII and Shunera XVI, with assemblages that include both Late Ahmarian and Early Epipalaeolithic small bladelet tools (Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 1997).

In Jordan, interpretations of Upper Palaeolithic sites have evolved over the course of the last 20 years. Known since the early 1980’s as a result of surveys by MacDonald (1988), Henry (1979, 1982) and Clark (Clark et al. 1992, 1994), it was unclear from the beginning if and how these eastern Levantine sites fit into the established Ahmarian and Levantine Aurignacian cultural framework. Surveys and excavations in southern Jordan by Henry (1979) were among the first well-documented examples of the Upper Palaeolithic in the eastern regions of the Levant. The lithic assemblages at the rockshelters of Jebel Humeima (J412), Tor Aeid (J432), and other sites in southern Jordan were initially identified as Levantine Aurignacian (Henry 1982, Coinman and Henry 1995), but more recent evaluations have demonstrated that the technology in these assemblages is clearly Ahmarian (Williams 1997a, b; Kerry 1997a). After the initial identification of Upper Palaeolithic sites through surveys in the al-Hasa basin by MacDonald (1988), preliminary investigations at Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) identified this site as Levantine Aurignacian (Clark et al. 1987, 1988), while later subsurface investigations indicated the possibility that both the Levantine Aurignacian and the Ahmarian were present at WHS 618 (Coinman 1990, 1993). This assessment has since been revised, especially on the basis of renewed excavations in 1997 (Coinman 1997a, b, c; 1998a, b; 2000; Olszewski et al. 1998). Together with newly identified Ahmarian sites, the data from the al-Hasa area provide new insights into the nature of the Ahmarian technocomplex.

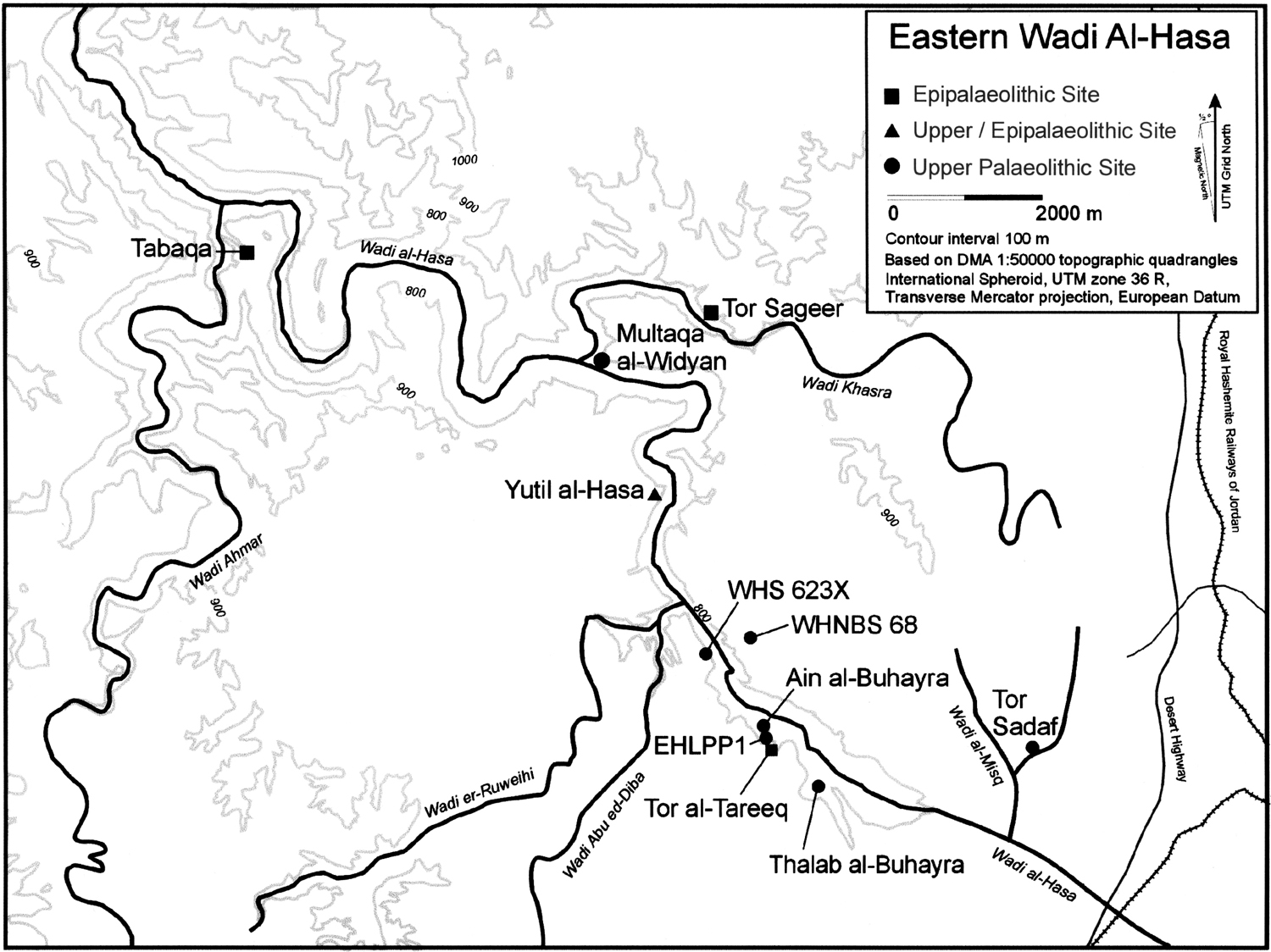

Upper Palaeolithic sites in the Wadi al-Hasa area (Fig. 13.1) now provide an extended chronology for the Ahmarian, beginning with the undated Early Ahmarian at Tor Sadaf and ending with the Late Ahmarian ca. 19,000 bp (Fig. 13.2). The Tor Sadaf assemblage probably dates to 30–38,000 bp based on similarities with other dated Early Ahmarian assemblages, such as Boker A in the Negev (Marks and Ferring 1988; Marks 1993; Monigal herein), Abu Noshra I–II (Phillips 1988, 1994) and Qadesh Barnea (Gilead and Bar-Yosef 1993) in Sinai. Indeed, the Ahmarian assemblage at Tor Sadaf may date earlier given its direct stratigraphic relationship to and origin within earlier transitional occupations at the site (Coinman and Fox 2000; Fox 2000, herein; Fox and Coinman 2000). Two other sites exhibit transitional and very early Upper Palaeolithic characteristics but have only been subjected to limited investigations in order to evaluate the nature and extent of such early technologies. These are Multaqa al-Widyan (WHNBS 195) at the confluence of Wadis al-Hasa and Khasra (Olszewski et al. 1998:62), and northern areas of Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) (Coinman 2000:147). Extensive surface assemblages recovered in 1984 from the large, open-air site of Ain al-Buhayra (Clark et al. 1987), in conjunction with evidence from subsurface testing in 1997 across the site (Olszewski et al. 1998), have revealed a long technological sequence. This includes deflated transitional Middle/Upper Palaeolithic and Early Ahmarian components in the far northern part of the site, which are known only from the remnant surface assemblages.

Although undated, the technology of the knapping site of WHS 623X with 11 refitted cores is Early Ahmarian (Lindly et al. 2000), as is the small, untested site of WHNBS 68, both near the juncture of the Wadi al-Hasa and the Wadi er-Ruwayhi (Olszewski et al. 1998:56). The recently tested site of EHLPP 1 exhibits a clearly defined Early Ahmarian core technology and tool assemblage, as well as a later Ahmarian occupation in the upper levels (Olszewski et al. 1998; Coinman 2000).

One of the more interesting results of recent investigations by the Eastern Hasa Late Pleistocene Project (EHLPP) has been the discovery of a late phase of the Early Ahmarian at Thalab al-Buhayra (EHLPP2). Two of the three areas excavated to date have produced radiometric dates between ca. 25–24,000 bp in association with assemblages that exhibit technological and typological characteristics most closely related to the Early Ahmarian (Table 13.1) (Coinman et al. 1999; Coinman 2000). Locus C at Thalab al-Buhayra documents one of the earliest known occupations at this site and is dated by an AMS radiocarbon date to 25,690±100 bp (Beta-129818), although there is new evidence of an earlier occupation below this one (Olszewski et al. in press). Locus E at Thalab al-Buhayra is stratigraphically above and horizontally separated from Locus C by some 20 m. A hearth at Locus E has been dated to 24,900±100 bp (Beta-129817).

Fig. 13.2 Chronology of Upper Palaeolithic sites in Wadi al-Hasa.

The relatively later Early Ahmarian assemblages at Thalab al-Buhayra appear to co-occur with some of the Late Ahmarian assemblages at Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) (see Table 13.1). On the middle slopes of the site in Areas F and C, the Late Ahmarian is represented in dense, derived deposits (Area C) and in dark marshy organic sediments (Area F), which have been dated to 25,590±440 bp (Beta-55928) (Schuldenrein and Clark 1994:34). In the southern portion of the site at the spring (formerly referred to as Areas H and I), expanded excavations were carried out in 1997. Four radiocarbon dates have been obtained from the stratified sequence of lacustrine marls, spring tufas, and cultural sediments that form the springtufa formation in this portion of the site (Coinman 2000:150). The stratigraphically lowest date at the spring tufa formation is 23,560±250 bp (Beta-55931) (Schuldenrein and Clark 1994:34), which dates an underlying organic marsh silt band that occurs between layers of marls and is ca. 20 cm below the lowest known cultural deposits at the spring. Above this is an early occupation that is located between 60–80 cm below the surface. A 1 m2 test unit revealed an assemblage dominated by the remains of large fauna and undiagnostic lithics. Directly above this early occupation at ca. 60 cm below the surface, soil sediments have been dated to 18,960±580 bp (Beta-55933) (Schuldenrein and Clark 1994:34). This is clearly anomalous since it is succeeded by a cultural hiatus and consolidated, inter-stratified tufa and marl sediments some 25 cm thick. These, in turn, are overlain by a well-dated Late Ahmarian occupation. The upper loose cultural sediments contain a high density of lithics and a well-preserved faunal assemblage in association with numerous hearth remnants, three of which have been radiometrically dated. One, dated to 23,500±270 bp (Beta-56424) was exposed on the south side of the tufa formation (Schuldenrein and Clark 1994:34). Another hearth was exposed through excavation (Feature 1, Test I) and dated to 20,300±600 bp (UA-43951) (Clark et al. 1987:40; Schuldenrein and Clark 1994:34). Charcoal-laden sediments from a third hearth (Feature 2, E68, N42) are dated to 20,670±600 bp (Beta-118757) (Coinman 2000:150).

During this same time period, there is one other well-dated Late Ahmarian site in the al-Hasa basin. This is the rockshelter of Yutil al-Hasa (WHS 784), first tested in 1984 (Clark et al. 1987; Olszewski et al. 1990) and reopened in 1993 (Olszewski et al. 1994; Olszewski 1997) and 1998 (Coinman et al. 1999). Charcoal from one of the lowest levels at this site in Unit A (Level 19) has been dated recently to 22,790±80 bp (Beta-129813) (Olszewski, herein), while a hearth in the upper levels of the unit (Level 2A) was dated to 19,000±1300 bp (UA-4396) (Clark et al. 1987:47). Therefore, the Late Ahmarian at Ain al-Buhayra and Yutil al-Hasa provides solid dates for the latest phase of the Ahmarian. The occupations at Ain al-Buhayra appear to span a period from ca. 25–20,000 bp and overlap the waning Early Ahmarian, as it is currently known from Thalab al-Buhayra. Similarly, the Late Ahmarian now appears to overlap with the Early Epipalaeolithic at the site of Tor Sageer (see Olszewski 2000 and Olszewski herein for a discussion of the Late Upper Palaeolithic and the Early Epipalaeolithic in the Hasa basin).

Table 13.1 Radiocarbon Dates from Upper Palaeolithic Sites in Wadi al-Hasa.

*Date appears to be anomalous as it occurs stratigraphically within older dated contexts.

Until recently it was difficult to identify the origins of the Ahmarian in the Wadi al-Hasa basin. There appeared to be abundant late Upper Palaeolithic sites in the Hasa, but Early Ahmarian sites were unknown. Middle Palaeolithic sites with Levallois technologies have been documented at Ain Difla (WHS 634 – Tabun D type) (Lindly and Clark 1987, Clark et al. 1997), and at WHS 621 (Clark et al. 1987; Potter 1993). With the excavations at Tor Sadaf, we are now able to anchor the origins of the Ahmarian in the transitional levels at this rockshelter site. The Early Ahmarian evolves very unambiguously and directly out of a late transitional technology in a continuous strati-graphic sequence at Tor Sadaf (Fox and Coinman 2000; Coinman and Fox 2000; Fox 2000 and herein). The transitional assemblages have been divided into earlier (Tor Sadaf A) and later (Tor Sadaf B) occupation periods2 based on gradual changes in core reduction strategies, debitage, and tool production. The overlying early Upper Palaeolithic levels, in turn, exhibit important related changes from the underlying transitional levels. Thus, a true Upper Palaeolithic blade technology emerges gradually from at least two earlier transitional phases rather than appearing abruptly as a stratigraphically separate occupation. Fox (herein) provides a more complete discussion of the changes between the transitional and the Early Ahmarian assemblages at Tor Sadaf.

Evidence from other Upper Palaeolithic sites in the al-Hasa basin now suggests that the Upper Palaeolithic Ahmarian technology that emerges from the transitional levels at Tor Sadaf continues throughout the time range of ca. 38–19,000 bp. Ahmarian technology and typology include core reduction techniques favouring the soft hammer and punch techniques, core rejuvenation strategies comprised of core tablets and ‘platform blades’ (described below), reduction emphasizing blade and bladelet production, and selection of elongated blanks for pointed tools. While technological strategies remain relatively stable, tool typologies are more variable, and pointed implements evolve into smaller point types. In order to gain a sense of how assemblages that occur at different sites and at different points in time might be related in a transgressive temporal sequence, Ahmarian technological and typological attributes are examined below. This is done in order to evaluate and monitor temporal continuity and change representing ca. 20,000 years in the sequence of assemblages in the al-Hasa area.

Different reduction strategies have been attributed to the core technology of the Ahmarian technocomplex (Ferring 1980, 1988; Marks and Ferring 1988). Early Ahmarian core reduction has been described as a serial reduction strategy in which multiple interior products were produced successively from the same core, while Late Ahmarian reduction strategies are characterized as having multiple core reduction strategies (Ferring 1988:334). Core reduction in the al-Hasa Early Ahmarian assemblages reflects strong similarities in strategies to those described by Ferring (1988:342) for Early Ahmarian technology. The core assemblages exhibit a ‘specialized’ reduction strategy for the production of specific tools, such as points (e.g., el-Wad points) (Ferring 1988:342). Production of elongated non-cortical or interior blades and large bladelets appears to have been sequential as the core was reduced in size. Careful core preforming and the maintenance of core shape and core platforms are illustrated by distal trimming, platform edge abrasion, and elongated pyramidal shapes of discarded cores.

Late Ahmarian reduction strategies follow Ferring’s (1988:343) description of multiple strategies, as well. Two reduction strategies are inferred in which large blade cores were used to produce large blades, as well as secondary core blanks. The latter were thick flakes and blades that could be used as secondary bladelet cores. There is ample evidence in the al-Hasa Late Ahmarian assemblages for small discarded bladelet cores made on thick flakes or blades. There is also evidence for large blade as well as large flake tools, produced from large cores, many of which exhibit substantial amounts of cortex reflecting an early stage in the reduction of large blanks.

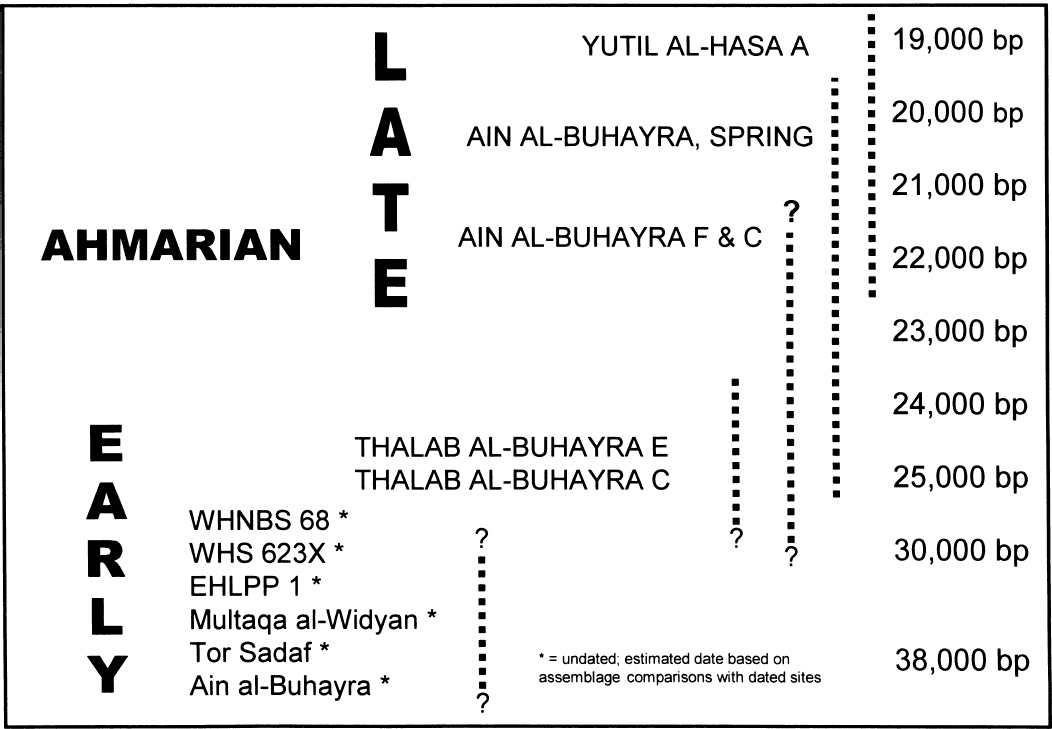

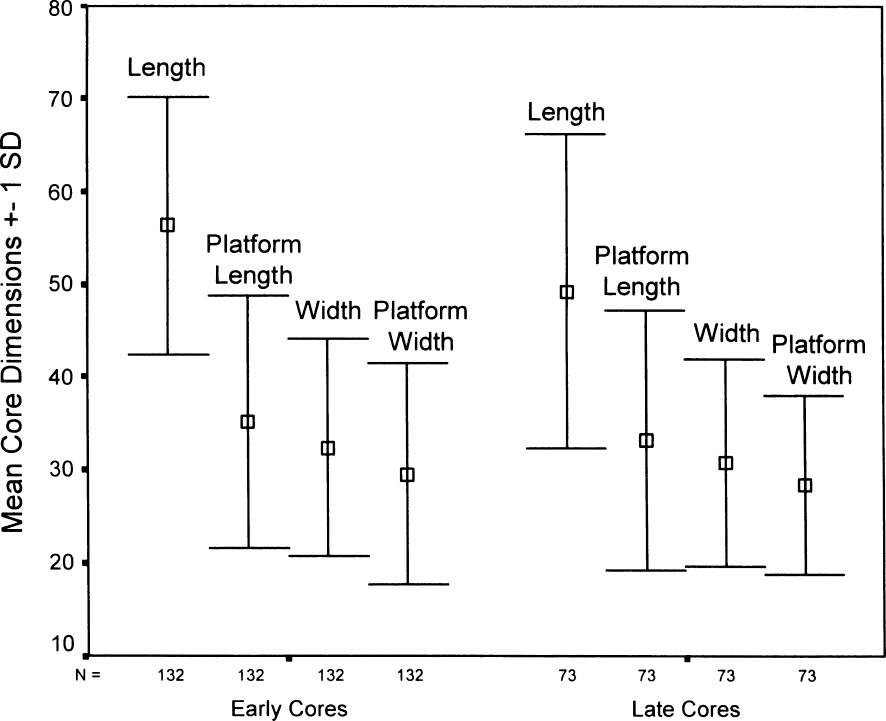

What is important in core reduction strategies in the Hasa assemblages are the long-term continuities in some aspects of overall core reduction from the Early to Late Ahmarian. Similar reduction strategies are reflected in overall core morphology, size, and platform characteristics (Fig. 13.3). Core size and platform size reflect specific reduction strategies and are correlated with the size and shape of the debitage produced from the cores, although the size of discarded cores may reflect other factors as well, such as economizing behaviour and overall raw material availability. In the al-Hasa area, there is only a slight trend for discarded cores and platform areas to become somewhat smaller through time, as debitage becomes dominated by smaller blades and bladelets (Fig. 13.4). Nevertheless, the overall strategy of maintaining a sub-pyramidal shape for elongated blanks is reflected in the similar length to width ratios of cores. Early Ahmarian cores exhibit a L:W ratio of 1.92 (11.7 sd, n= 132), while Late Ahmarian cores are less elongated with a ratio of 1.82 (1.0 sd, n= 73). Overall core dimensions of Early and Late Ahmarian cores reflect long-term continuity in core reduction while the production goals shift to smaller blanks.

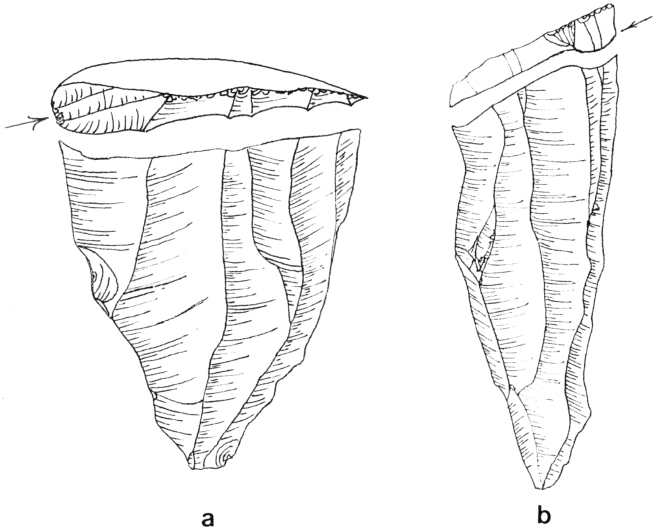

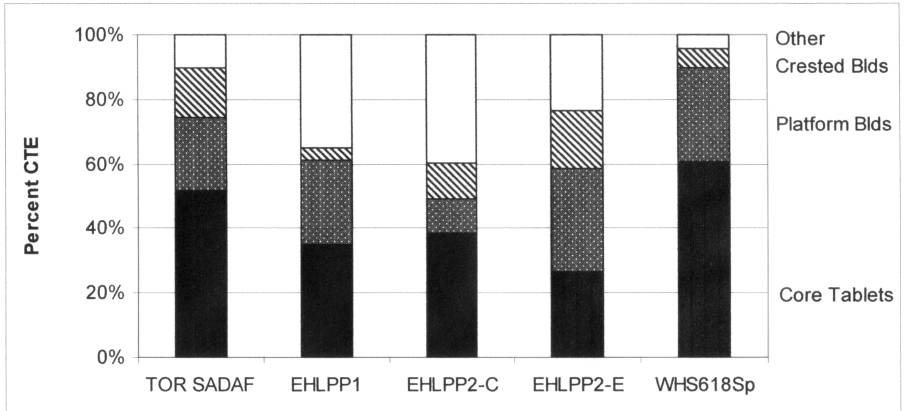

The use of ‘cresting’ or lames à crête as a preliminary blade core reduction technique is present but diminishes in Late Ahmarian assemblages (Fig. 13.5). In most cases, a relatively simple technique of setting up a core with an unfaceted platform was used, most likely as a result of the size and shape of raw material selected as cores. Based on abandoned cores, refitted cores, core tablets and tools made on core tablets, as well as successive refitted core tablets, the shape of many cores can be inferred to have been relatively thin, flat cortical nodules with a limestone cortex or rind. Rejuvenation of Ahmarian core platforms was dominated by the core tablet technique (Fig. 13.6), while removing a ‘platform blade’3 might have been a strategy for re-orienting a platform or initiating a new platform on the back of the core, usually at 90° to the original platform (Coinman 1997b:116;1998a:49). These transverse platform blades appear to be ‘half-crested’ because they exhibit a portion of the previous platform along one side of their main dorsal ridge but were struck from the back of the core’s platform. This technique has been documented in other Ahmarian assemblages at sites in the southern Sinai at Abu Noshra II and in the central Negev at Ein Aqev East (Ferring 1977:88, 1980:59; Coinman 1990:265), and in south Jordan at Tor Aeid, Tor Hamar, and Jebel Humeima (Coinman and Henry 1995:145,155,163,172). The long-term use of these technological techniques is demonstrated in their persistence at both Early and Late Ahmarian sites in the al-Hasa region.

Fig. 13.3 Cores from Ahmarian sites in Wadi al-Hasa: a, b, d – Early Upper Palaeolithic levels at Tor Sadaf rockshelter; c – EHLPP1; e – Ain al-Buhayra. Area C; F – Ain al-Buhayra Spring.

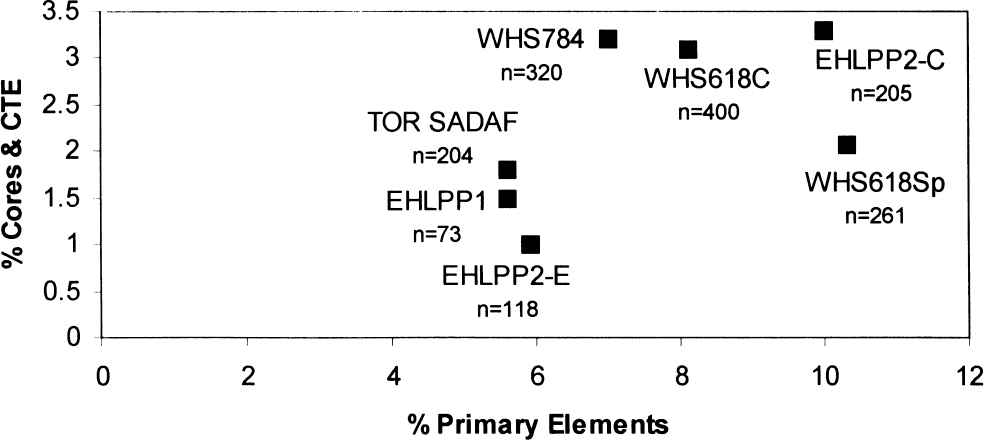

Proportions of cores, core trimming elements (CTE), and primary cortical elements are strong indicators of on-site initial core reduction and can be used to reconstruct reduction sequences occurring at sites or missing segments of the sequence that may have occurred elsewhere. Primary cortical elements include debitage with approxi-mately 50% or more cortex. Comparisons of the relative proportions of initial stage reduction elements represented at Ahmarian sites in the al-Hasa area indicate important differences among the sites with at least two distinct site groupings (Fig. 13.7). The Early Ahmarian sites of Tor Sadaf, EHLPP1 and Thalab al-Buhayra, Locus E (EHLPP2-E) all exhibit relatively low intensity primary reduction activities with cores and core trimming elements ranging from 1.0–1.8% and primary elements represented by 5.6–5.9%. This contrasts with two Late Ahmarian sites – Yutil al-Hasa (WHS 784) and Ain al-Buhayra, Area C (WHS 618 C) – in which high frequencies of all initial stage reduction elements are present. The most dramatic differences among the sites are represented at the Early Ahmarian site of Thalab al-Buhayra, Locus C (EHLPP2-C) with the highest proportions of all primary reduction elements. The Late Ahmarian site of Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618 Spring) contains equally large numbers of primary elements but lower proportions of cores and core trimming elements. For the most part, primary elements are cortical flakes rather than cortical blade/lets, and at EHLPP2-C, these are large primary flakes struck from very large cores with a mean of 64.9 mm (sd 9.85) on an initial sample of nine cores. When the debitage assemblages are restricted to relative proportions of flakes (excluding small trimming flakes) and blade/lets, flake debitage represents close to 50% or more of the restricted debitage assemblages: WHS 784 (73%), Thalab al-Buhayra (E-47.3%; C-54.4%), and WHS 618 Spring (48.9%). This is in spite of the fact that each of these assemblages has a well-developed blade and bladelet component. It emphasizes the importance of flake debitage as a primary indicator of on-site reduction activity rather than a diagnostic criterion of specific lithic cultural traditions.

Fig. 13.4 Mean dimensions of cores from sites in Wadi al-Hasa. (Platform width = lateral width; Platform length = length from front face to back of platform)

Fig. 13.5 Ahmarian core trimming and rejuvenation techniques: a) platform blade; b) core tablet.

Fig. 13.6 Relative proportions of the predominant types of core trimming elements (CTE) in debitage assemblages at sites in Wadi al-Hasa.

Fig. 13.7 Primary reduction elements at sites in Wadi al-Hasa. Primary elements are defined by at least 50% cortex.

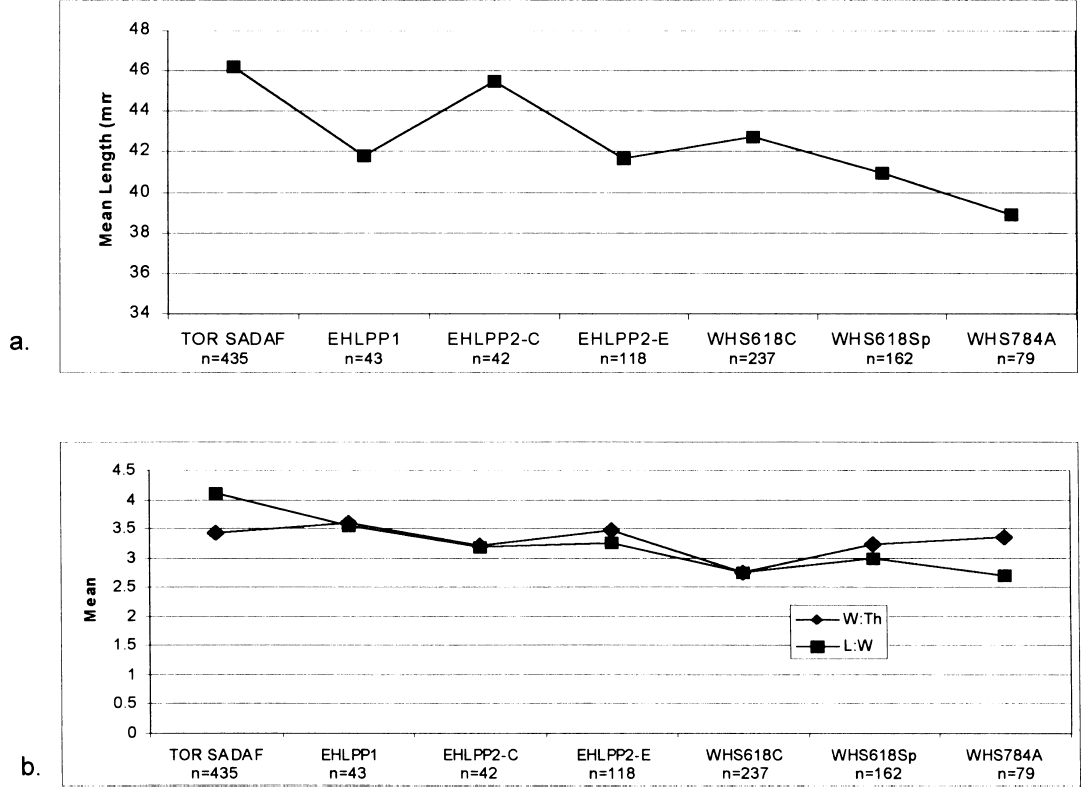

Fig. 13.8 Changing dimensions in blade/let debitage in Ahmarian sites in Wadi al-Hasa: a) length; b) ratios of length:width and width:thickness.

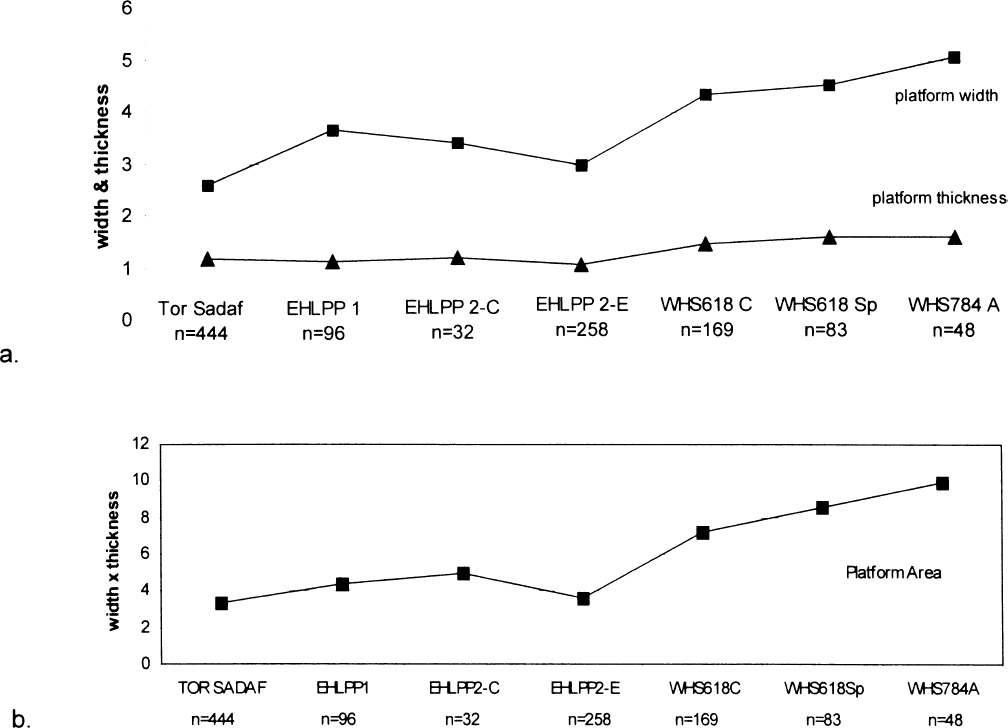

In each of the Ahmarian assemblages in the Hasa blades and bladelets comprise a significant subset of blank production. The mean size of blade-like debitage decreases through time as production shifts to smaller debitage (Fig. 13.8a). Bladelets become shorter but less elongated. Early Ahmarian bladelets at Tor Sadaf and EHLPP1 are the most elongated with mean length:width ratios of 4.0 and 3.5, respectively (Fig. 13.8b). The diminutive size of debitage platforms in assemblages throughout the temporal range of the Ahmarian in the al-Hasa area suggests that Ahmarian blade technology most likely emphasizes an indirect punch technique rather than soft hammer to remove blades and bladelets with such small platforms (Fig. 13.9a, b). Interestingly, the lateral widths4 of platforms are the smallest on the longest bladelets, as reflected in the extremely small platforms on bladelets from Tor Sadaf that average only 2.5 mm in width. Platform width increases by Late Ahmarian times, while thickness remains relatively stable at approximately 1 mm.

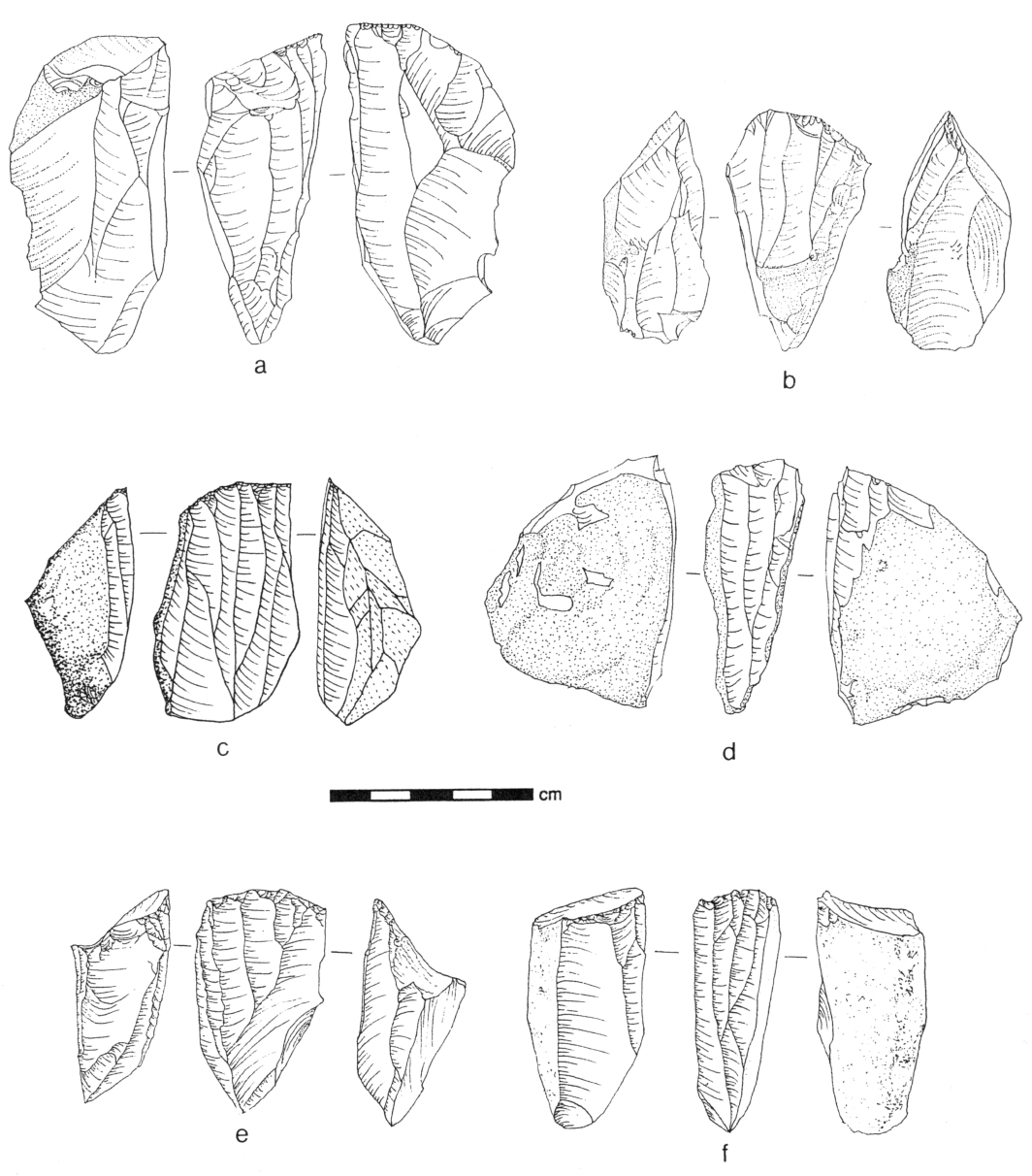

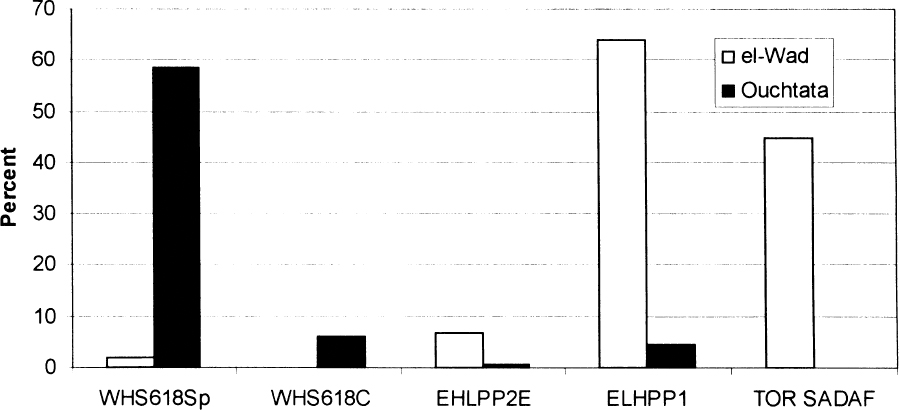

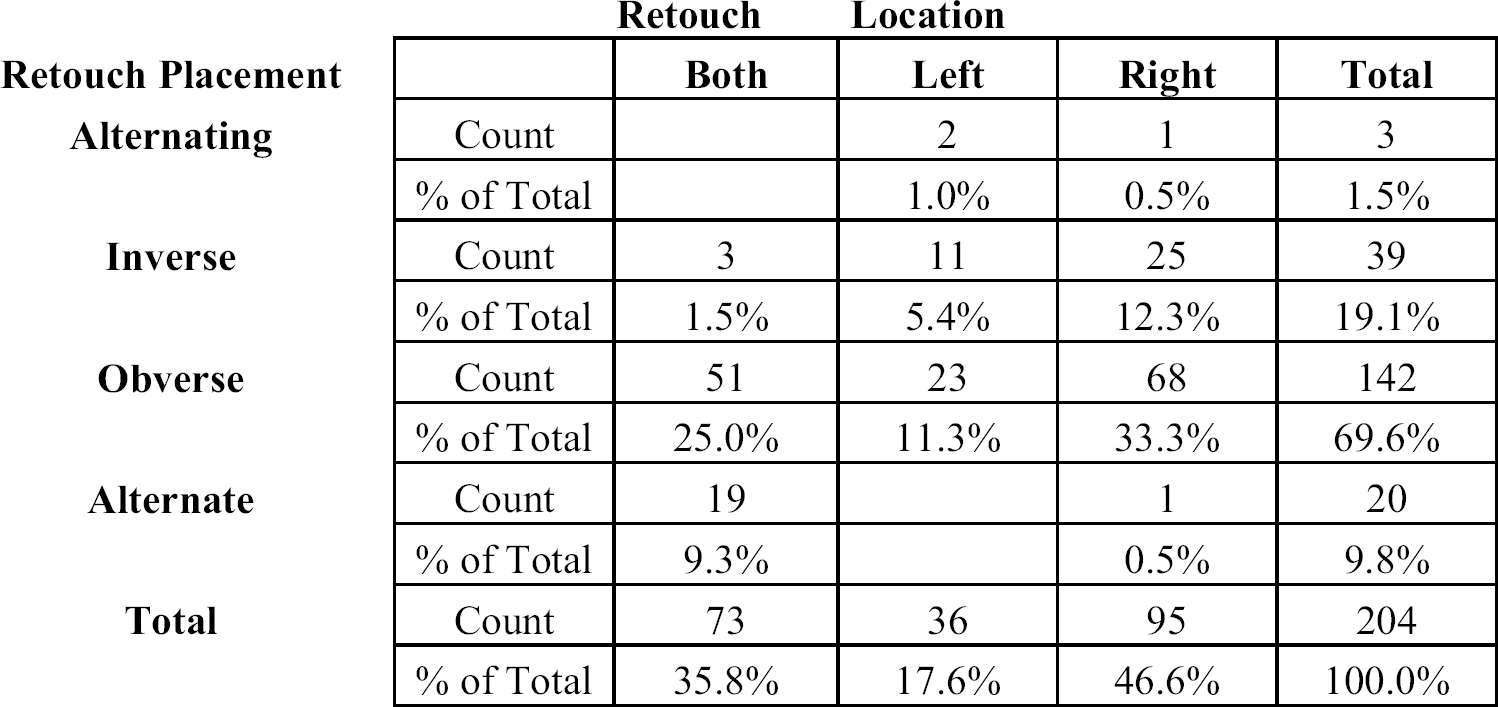

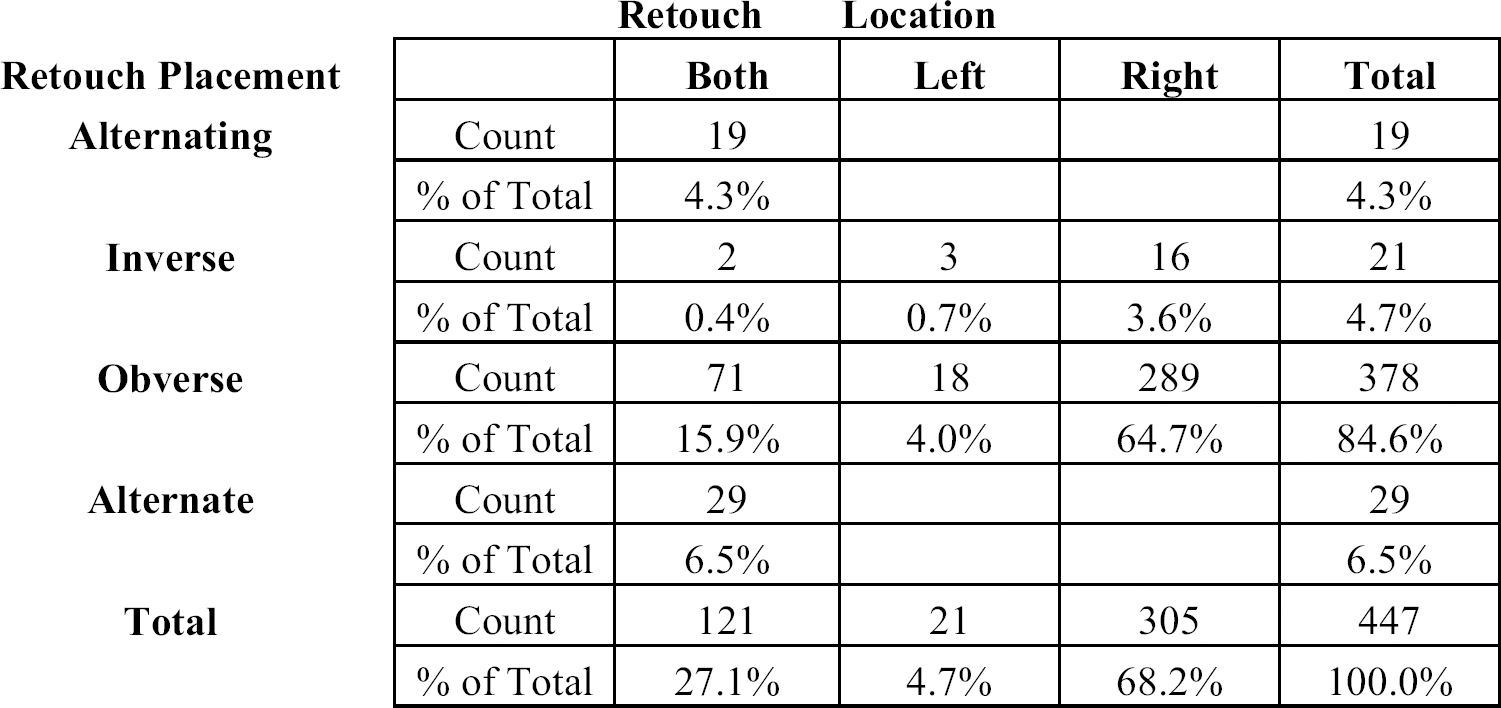

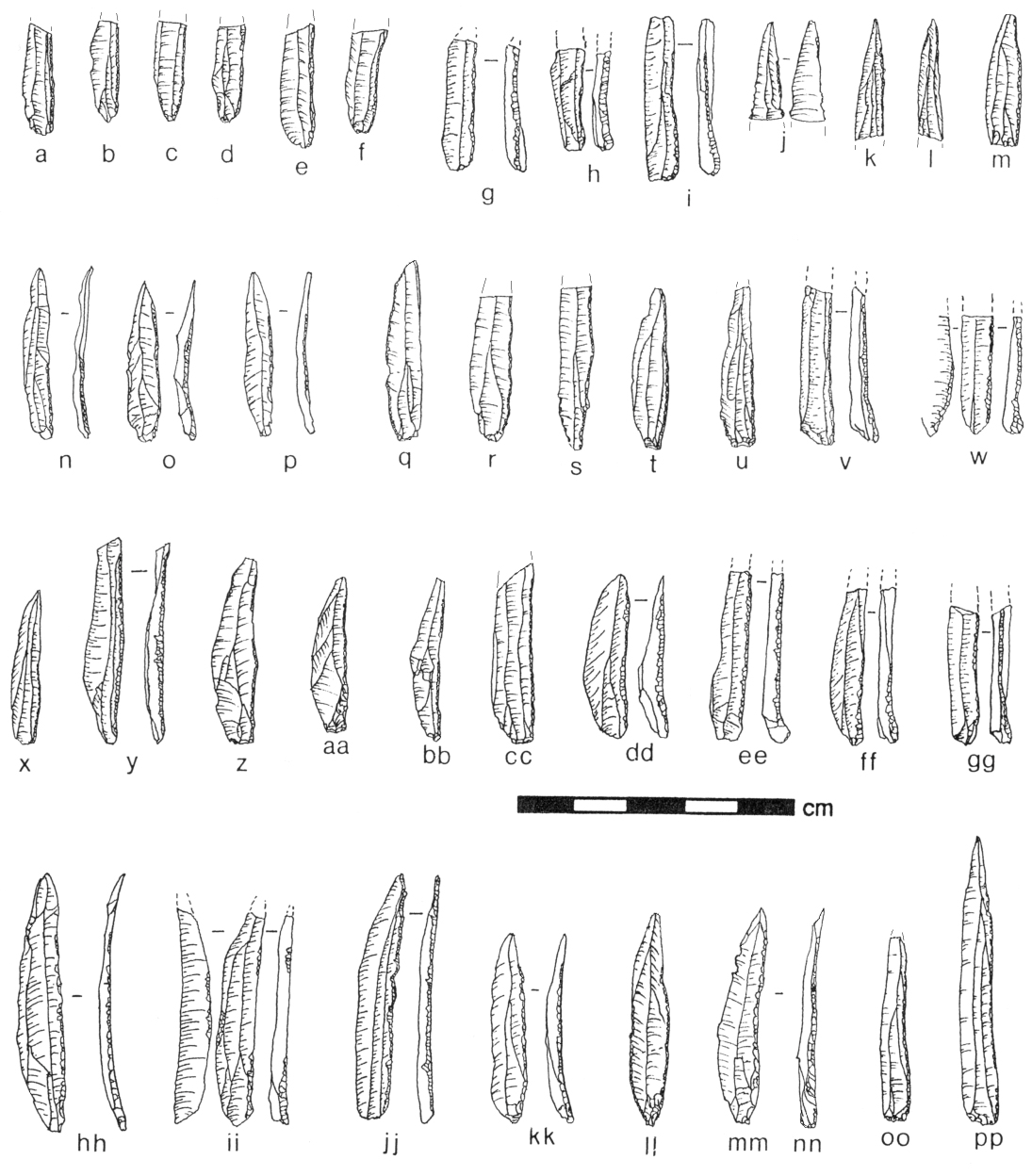

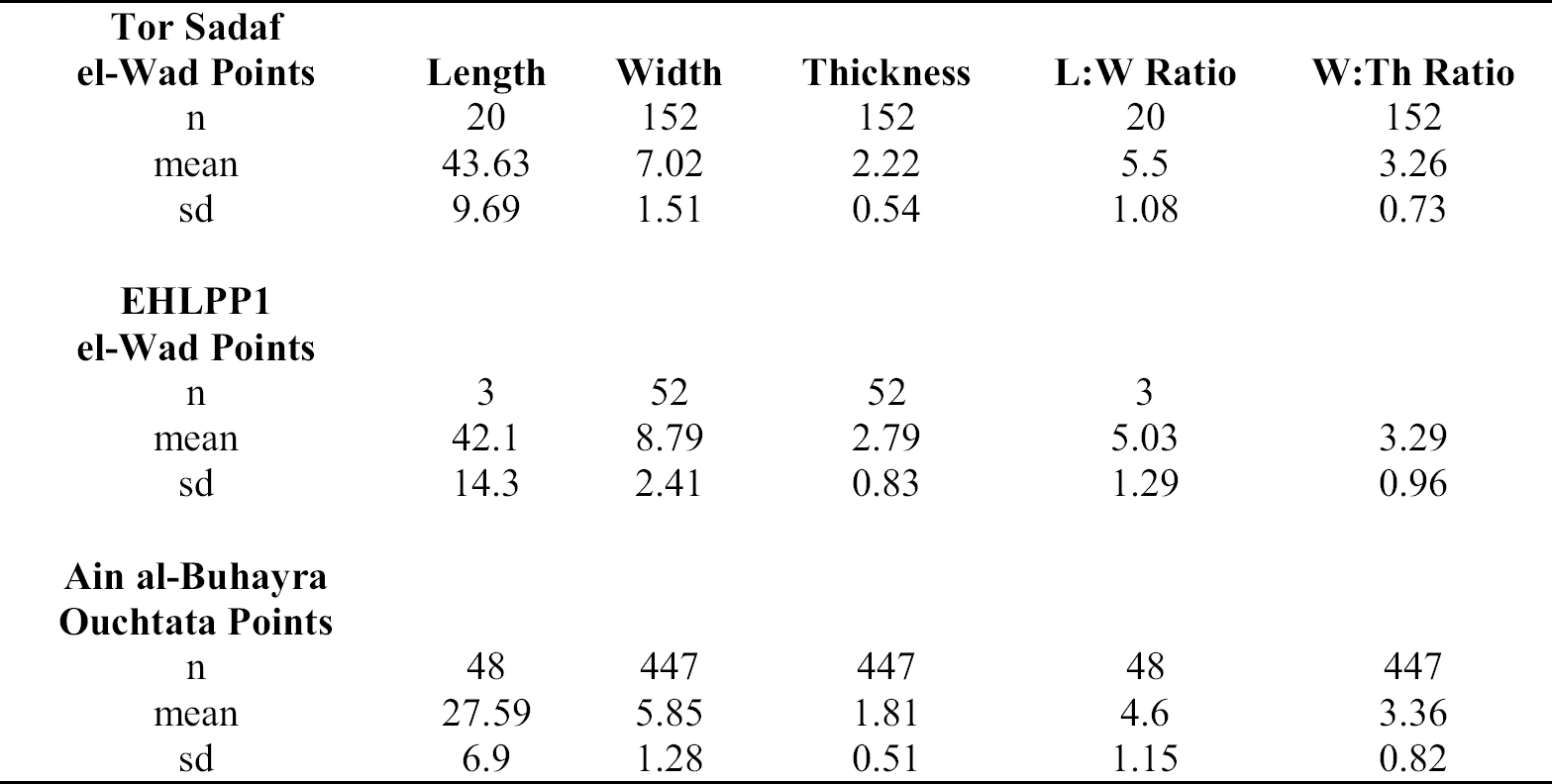

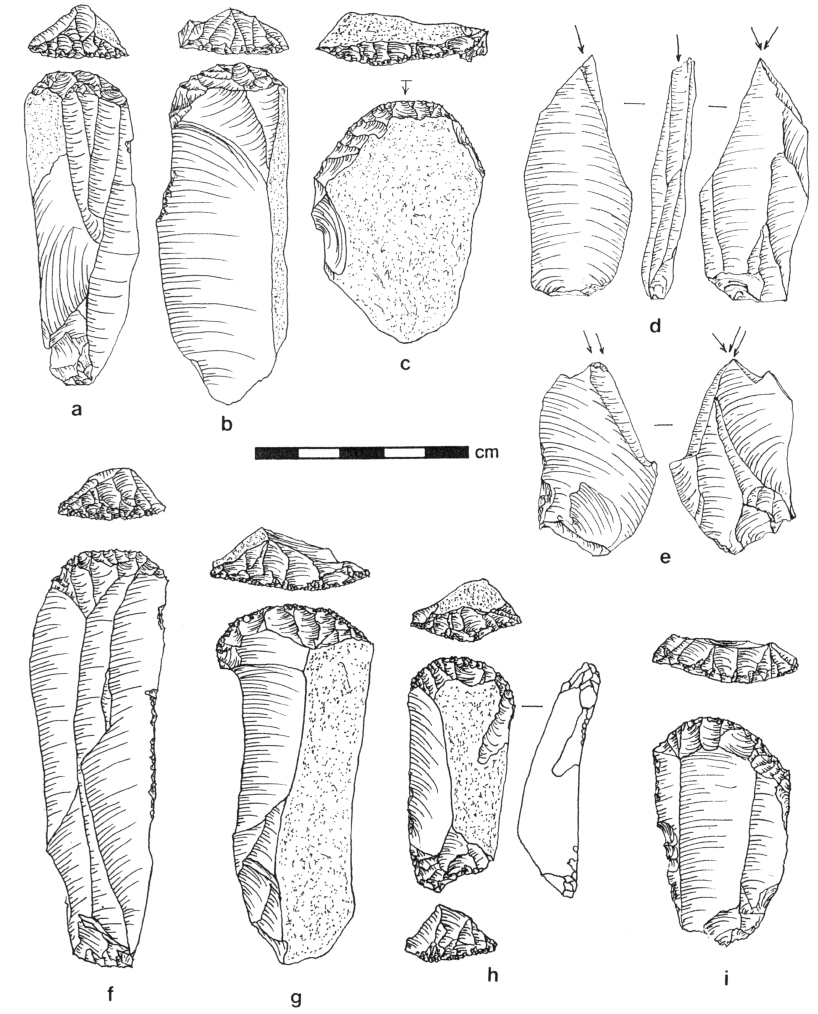

Elongated blanks in Ahmarian assemblages were produced and used primarily for pointed implements made on the small blades and bladelets. Initially, the emphasis was on producing a variety of el-Wad point types and later on the more narrow Ouchtata points that have been found primarily at Ain al-Buhayra and Yutil al-Hasa (Fig. 13.10). This is supported by the size and facet dimensions of discarded cores. Typological differences between early and late stages are limited, with the most important tool differences represented by differences in the amount, placement (face), location (edge), and type of retouch used to shape blade/lets into el-Wad points (Table 13.2). The earlier el-Wad points exhibit abrupt to semi-abrupt retouch along the lateral edges, often grading into a finer, less steep retouch around the distal tips (Fig. 13.11). Correlation between the location of retouch and the placement of retouch shows that the el-Wad points tend to exhibit retouch on both edges, often by inverse retouch (19.1%), but more commonly as obverse retouch (69.6%). Retouch on both edges or alternating inverse/obverse retouch along the same edge is less frequent.

Fig. 13.9 Dimensional change in bladelet platform technology associated with punch technique: a) platform width and thickness; b) platform area (width × thickness).

Fig. 13.10 Changing frequencies of pointed tools – el-Wad points and Ouchtata points – in Ahmarian sites in Wadi al-Hasa.

Table 13.2 Cross-tabulation of retouch attributes on el-Wad points from Tor Sadaf (n= 152) and EHLPP1 (n= 52).

Retouch placement = face or faces of a blank (Marks 1976c:376)

Retouch location = lateral edges

Alternate = inverse and obverse retouch on different lateral edges (Marks 1976c:376)

Alternating = inverse and obverse retouch alternating along the same edge (Marks 1976c:376)

Table 13.3 Cross-tabulation of Retouch Attributes on Ouchtata Bladelets and Points from Ain al-Buhayra (WHS618) Area C, n= 57; Spring, n= 390.

Retouch placement = face or faces of a blank (Marks 1976c:376)

Retouch location = lateral edges

Alternate = inverse and obverse retouch on different lateral edges (Marks 1976c:376)

Alternating = inverse and obverse retouch alternating along the same edge (Marks 1976c:376).

By the Late Ahmarian, retouch on bladelets and points had become more standardized and occurred predominantly on the right obverse edge (64.7%), while inverse retouch is found only rarely (Fig. 13.12 and Table 13.3). Retouch on proximal areas tends to square off the proximal ends of Ouchtata points and bladelets. There are fewer examples of deliberate retouch to shape distal ends into retouched points amongst the Ouchtata pieces. Complete Ouchtata points and distal fragments, however, indicate that most pieces were naturally pointed. Although some pointed tool types have been defined precisely on the basis of deliberate retouching to form a point, others have not (e.g., Levallois points). Whether we type these pointed implements as specific point types or type them as retouched and partially backed blades/bladelets, they remain ‘pointed’ implements that contrast sharply in retouch and morphology with the more standardized backed and truncated microliths that are typically found in Early Epipalaeolithic assemblages.

Fig. 13.11 El-Wad points from Early Ahmarian sites: b – d, l, p, q, s, t – Tor Sadaf; e-h, o – EHLPP 1; a, i-k, m, n, r – Thalab al-Buhayra (EHLPP 2); u – Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618), Early Upper Palaeolithic surface material, northern area of site.

Fig. 13.12 Ouchtata points and bladelets with Ouchtata retouch from Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) Spring area.

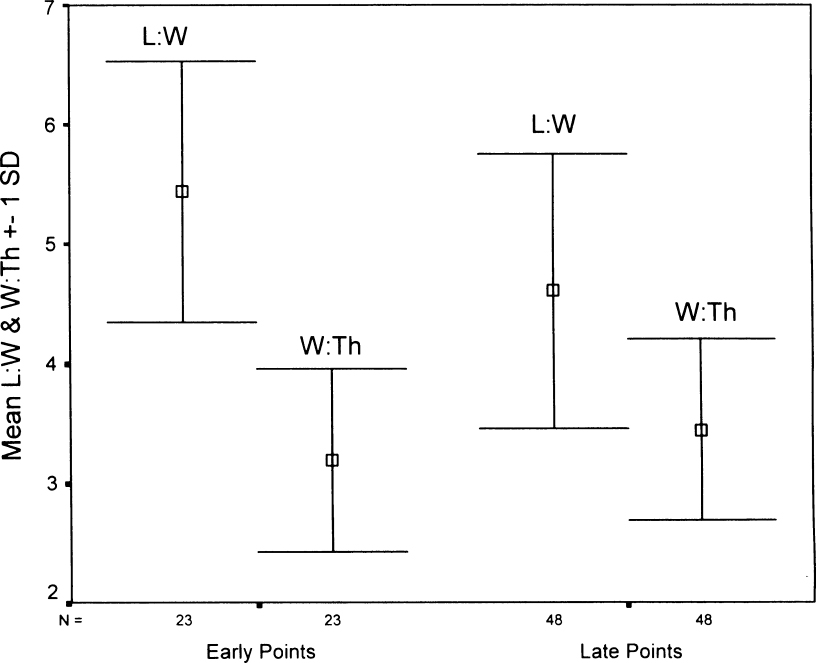

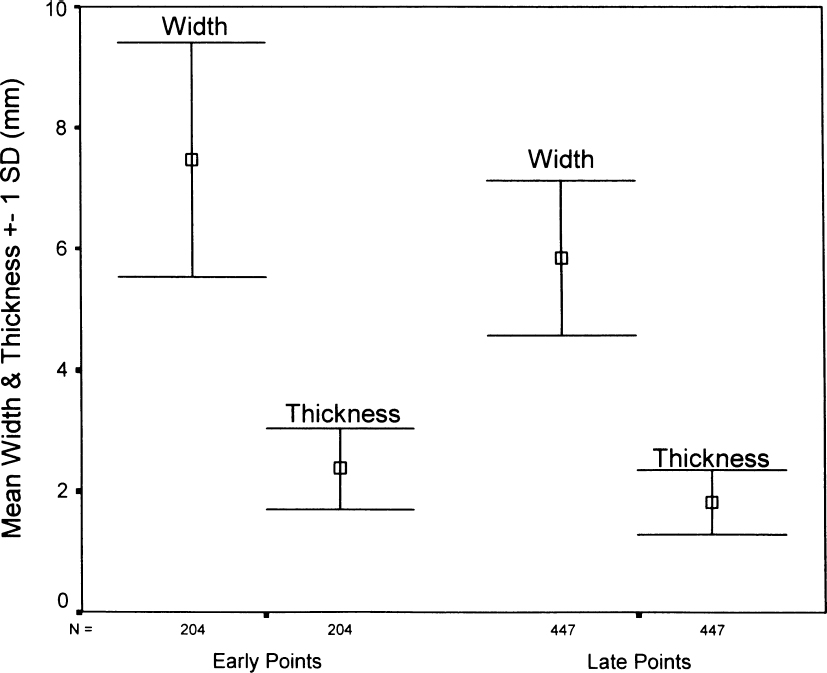

The preponderance of similarities in retouch placement, location, and style between complete el-Wad points and Ouchtata points and their associated fragments argues strongly for a typological and functional relationship between the two point types as one type appears to evolve into the other. Limited use-wear or microwear studies have been completed on these tools, but Williams (1997a) has provided convincing evidence that el-Wad points from the Early Ahmarian rockshelter site of Tor Aeid (J432) were used as projectiles, as well as for other functions. Becker (1999, herein) indicates that many el-Wad points at Abu Noshra were used as perforating tools. The shape and symmetry of el-Wad points suggest their primary functions were as projectiles. There have been no comparable microwear studies on the Ouchtata bladelets, and, therefore, attributing an analogous projectile function is inferred on the basis of techno-typological similarities to the el-Wad points. Other than size, there are no technological and few typological differences between el-Wad points and Ouchtata points when the al-Hasa data are compared to each other so that variability in some aspects of retouch and size might be the only distinguishing characteristic. El-Wad points average 42 mm in length, while Ouchtata points have a mean of about 27 mm (Table 13.4). Length to width ratios vary slightly between the two groups of points (Fig. 13.13) with el-Wad points exhibiting greater elongation. Width to thickness ratios, however, are relatively close. Mean blank thickness is very similar for both types, and variability in mean blank width is the only attribute that reflects overall differences in size (Fig. 13.14). The end result is a smaller, less elegant, less formal ‘point’. Some of the retouch varies between the two groups of artefacts. Perhaps the differences in retouch type and intensity might be a function of the variation in the thickness of blanks. Ouchtata retouch, by definition, occurs along edges of small, very thin bladelets and consists of retouch that grades from fine retouch to extremely minute alteration of an edge (Marks 1976c:377, after Tixier 1963:40). Thus, as overall blank size decreases, some of the retouch changes in response to thinner bladelets, but the final tool maintains the overall shape of a pointed implement.

Fig. 13.13 Mean length to width and width to thickness ratios of Early and Late Ahmarian points from sites in Wadi al-Hasa.

Fig. 13.14 Mean width and thickness dimensions of Early and Late Ahmarian points in Wadi al-Hasa.

Table 13.4 Dimensional Attributes of el-Wad Points from Early Ahmarian Tor Sadaf and EHLPP 1 and Ouchtata Points at Late Ahmarian Ain al-Buhayra.

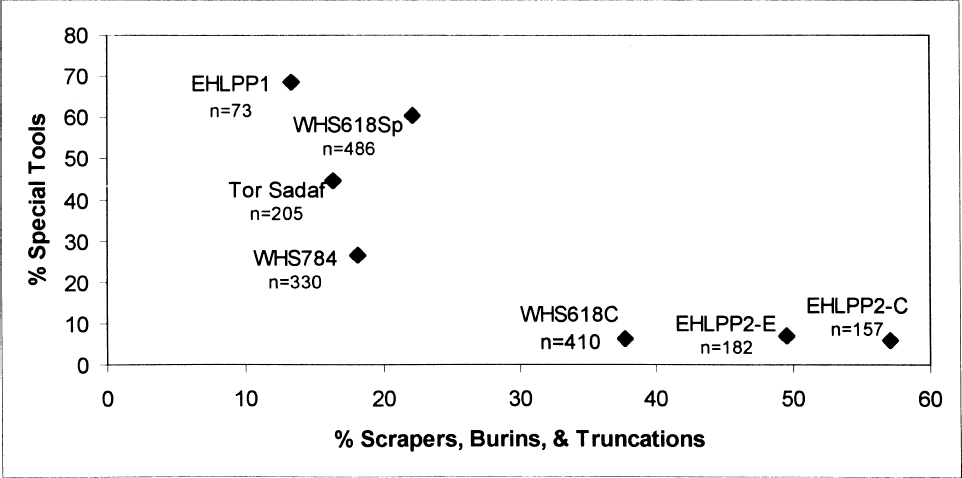

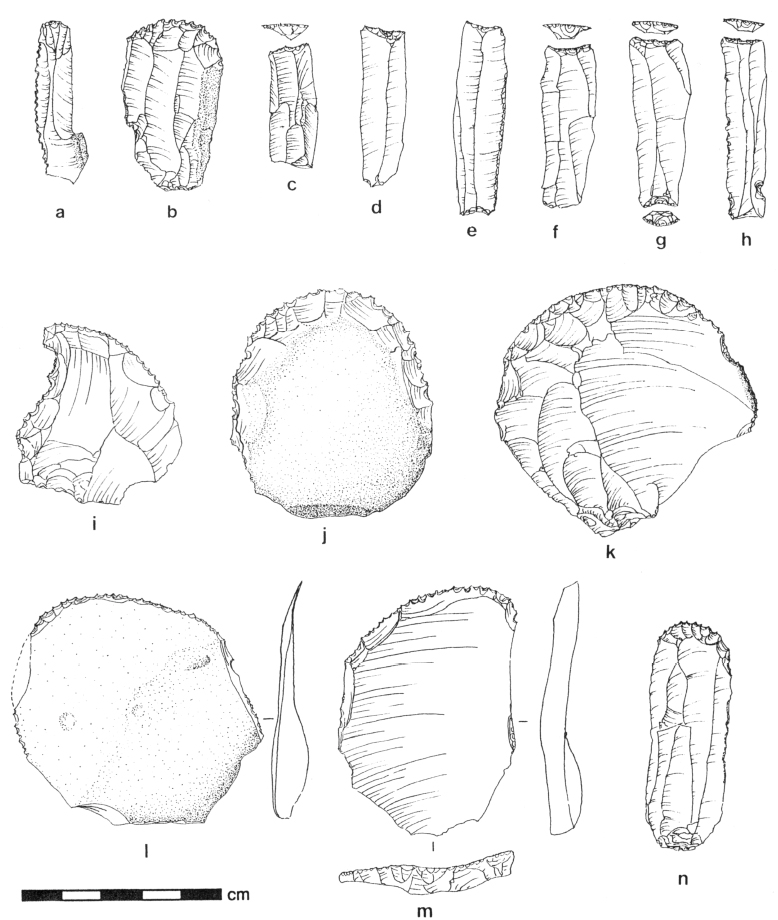

Although the primary emphasis in Ahmarian assemblages appears to be on elongated blanks for the production of pointed tools, typical Upper Palaeolithic tools were made on relatively large blanks throughout the Upper Palaeolithic. Ferring (1988:343) considers the production of large tools during the Early Ahmarian to be expedient and to be made on by-products of core preforming and maintenance during the initial stages of serial core reduction. He emphasizes that the Early Ahmarian specialized reduction strategy was aimed primarily at interior elongated blanks (Ferring 1988:342), but evidence from at least one site in the al-Hasa indicates that large cortical flake tools were most likely of primary importance in activities carried out at the site. During the Late Ahmarian, according to Ferring, there are divergent large tool requirements that result in multiple reduction strategies. Large tools are suggested to be made intentionally as part of one strategy involving large blade cores and separate from the production of small bladelets. In the al-Hasa area, there are two contrasting groups of Ahmarian sites in which larger tools are offset by smaller, more specialized tools. Scrapers, burins, and truncations make up the most important categories of large tools, while points and retouched bladelets represent special tools (Fig. 13.15). The most striking distributions are found again at Thalab al-Buhayra, Locus C (EHLPP 2-C), where scrapers of a wide variety outnumber all other tool categories (42.2%), while the other sites exhibit proportions of scrapers that are generally less than 20%. Burins are insignificant in all but two sites – the Late Ahmarian sites of Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618 C) and Yutil al-Hasa (WHS 784). Scrapers at Locus C in Thalab al-Buhayra include narrow endscrapers, as well as micro-serrated endscrapers and Ksar Akil flake scrapers (Besançon et al. 1975–7), which are found in the same context as primary reduction elements. Many of the scrapers were made on cortical flakes. Closely associated with the scrapers at this site are truncations, forming an unusual toolkit (Fig. 13.16). The combination of truncations and scrapers is strikingly similar to that recovered from Level 5 at Boker BE in the central Negev (Jones et al. 1983), although the latter has a much higher frequency of el-Wad points. The two sites date to approximately the same time range ca. 27–25,000 bp (Marks 1983b:37). The tool kit at nearby Locus E at Thalab al-Buhayra is similar in makeup to the Locus C tool kit, but scrapers and truncations occur in more equal proportions. Area C at Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) has an interesting mix of relatively more truncations, the highest percentage of burins, but significantly fewer scrapers (Fig. 13.17).

Fig. 13.15 Tool composition at sites in Wadi al-Hasa (percentages). Special tools are defined as el-Wad points and Ouchtata points and bladelets.

Fig. 13.16 Scrapers and truncations from Thalab al-Buhayra (EHLPP2). i-m – typical Ksar Akil scrapers; a, b, n – atypical micro-serrated tools; c, d, f, h – truncations; e, g – double truncations.

Fig. 13.17 Large tools from Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618): a, e, h, i – Area C; b - d, f g –Spring.

Assemblages that are dominated by more specialized blade and bladelet tools have been recovered from both Early and Late Ahmarian sites. These are Tor Sadaf, EHLPP 1, the Spring area of Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618 Spring), and Yutil al-Hasa (WHS 784), in which various sized pointed implements and finely retouched bladelets comprise significant proportions of their respective assemblages. Tor Sadaf and EHLPP 1, a rockshelter site and an open-air site, respectively, are dominated by el-Wad points and exhibit relatively lower primary reduction elements. Projectile point production or retooling activities might best describe activities at these sites. Major proportions of finely retouched bladelets, many of which are the small Ouchtata points (or fragments of such points) have been recovered from the Late Ahmarian sites of Ain al-Buhayra Spring Area, and Yutil al-Hasa (WHS 784) rockshelter. Primary reduction elements are significantly higher than at the other sites (see Fig. 13.7).

In summary, the Ahmarian sites exhibit well-patterned differences in tool kits that are most likely associated with different activities or a different range of activities that occurred at these sites, and where on- and off-site reduction activities obviously varied. Since large tools occur in varying proportions at both Early and Late Ahmarian sites and many have been made on primary elements, the reduction strategies appear to vary according to specific activities that were carried out at site. In the case of Thalab al-Buhayra (Locus C), interior blades and bladelets which would be predicted to be the primary focus of Early Ahmarian specialized reduction strategies were produced but in smaller quantities than flake debitage, especially cortical flake debitage. Many of these were used for large tools, as well as potentially large numbers of utilized flakes that were not formally retouched. If interior blades and bladelets were needed for pointed tools, they were not left at the site or at this area of the site. Rather, activities appear to have revolved around the larger tools – the scrapers and truncations, which were discarded in large numbers. A current study of flakes, both retouched tools and utilized flakes, is on-going and should help identify more specifically the on-site activities that required an emphasis on expedient large tools rather than the specialized tools made on interior products that are predicted in Ferring’s reduction models.

Examination of the debitage and tool assemblages in the al-Hasa area illustrates a long chronological sequence of evolving Ahmarian technology and variable typologies at rockshelters and open-air sites. Ahmarian sites in the al-Hasa basin exhibit specific technological and typological trends during the period from ca. 40–19,000 bp that place this series of sites squarely within the Ahmarian. The al-Hasa region techno-typological sequence is comprised of full-fledged Upper Palaeolithic Ahmarian blade core reduction, but some assemblages exhibit characteristics, such as flake-dominated debitage and tools, that often have been attributed to the Levantine Aurignacian (e.g., Gilead 1981a, Marks 1981a). These include varying proportions of large tools and debitage and a heavy emphasis on flakes, although these are found in conjunction with well-executed blade and bladelet components. Blank production and selection in these assemblages were directed at both large and small tools. Larger tools consisted of the classic Upper Palaeolithic tool types, such as endscrapers, burins, and truncations. These occur in variable proportions at sites in the al-Hasa basin, and they occur in both Early and Late Ahmarian assemblages but may be strongly associated with specific activities at some sites. Smaller tools consisting of specialized pointed implements, either el-Wad point varieties or Ouchtata points and bladelets, dominate tool composition in some Early and Late Ahmarian sites, as well. Late Upper Palaeolithic pointed tools that are found after 25,000 bp, however, are typically smaller than earlier points. After about 22,000 bp in the al-Hasa area, some of the early Epipalaeolithic sites or occupation levels overlap temporally with Late Ahmarian occupations. Low numbers of early Epipalaeolithic microliths and the microburin technique occur at the same time that Late Ahmarian Ouchtata bladelets are the predominant form of retouched bladelets at other sites (see Olszewski herein; al-Nahar 2000). At a number of other late Pleistocene sites in the Levant, Ouchtata bladelets in varying numbers occur in the same assemblages with typically Early Epipalaeolithic backed microliths. These sites – Azariq XIII, Shunera XVI, Ohalo II, Fazael X, and Masraq en-Naj – have been included in the Masraqan, which has been defined as Early Epipalaeolithic (Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 1997). Since all of these assemblages have clearly overlapping assemblages of retouched bladelets, they are both late Upper Palaeolithic and Early Epipalaeolithic in their typologies. Two other sites – Ain al-Buhayra (WHS 618) and Ein Aqev East (Ferring 1997) – have been included in the Masraqan, but their inclusion in the Masraqan is more tenuous. Neither of these two sites contains an assemblage of Epipalaeolithic microliths. Rather, both sites are dominated almost exclusively by bladelets with Ouchtata retouch and they share remarkable technological and typological similarities (Coinman 1990, 1993). In that respect, they fall more appropriately in the Late Ahmarian technocomplex (Ferring 1977, 1980, 1988; Marks and Ferring 1988).

The lithic assemblages from the al-Hasa area, when examined within a technological framework focused on reduction strategies suggest that differential proportions of tool types and subsets of debitage at Upper Palaeolithic sites are most likely a result of different on-site activities and thus, potentially different site functions. Furthermore, specific intra-site activities may have changed at some sites during different occupation periods within large, multi-component sites. Ongoing research of the Wadi al-Hasa assemblages seeks to define more clearly the articulation of technology with subsistence strategies at sites that exhibit a variety of intra-site lithic and faunal configurations within different site settings and preservation contexts. By focusing on a constellation of artefact assemblages and site features, we are able to move beyond the systematics of the Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and direct our attention at trying to understand larger issues of adaptive responses during the late Pleistocene when settlement and subsistence strategies were changing. Many of these were changes in human subsistence strategies associated with the exploitation of new varieties of plants and animals. At present, those changing strategies are only partially documented and incompletely understood.

Research at sites in the Wadi al-Hasa has been conducted with the permission of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, which has provided continued support over the course of many years, and for which we are all most grateful. Research on the Palaeolithic of the al-Hasa region under the aegis of the Wadi Hasa Palaeolithic Project (WHPP) and the Wadi Hasa North Bank Survey (WHNBS), 1984–93, was directed by G.A. Clark (Arizona State University) and supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and Arizona State University. Research by the Eastern Hasa Late Pleistocene Project (EHLPP), directed by D.I. Olszewski (Bishop Museum) and N.R. Coinman (Iowa State University), 1997, 1998 and 2000 has received primary funding from the National Science Foundation (SBR 9618766), the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (Gr. 6278), the National Geographic Society (Gr. 6695–00), the United States Information Agency (USIA), the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) in Amman, the Joukowsky Family Foundation, and the Graduate College and Department of Anthropology at Iowa State University. While in Jordan, ACOR and its staff have provided logistical support. This chapter has benefited from the helpful comments and suggestions of several reviewers. This is EHLPP Contribution #17.

1 The sample has been identified in previous publications as ‘spring/tufa sediments’ (Clark et al. 1987:40; Schuldenrein and Clark 1994:34) but might more accurately be described as ‘charcoal in tufa/marl sediments’ since the sediments come from a culturally-derived feature rather than a sterile tufa or lacustrine context.

2 The designations for the transitional occupation periods at Tor Sadaf replace the initial designation – ‘Transitional A’ and ‘Transitional B’ that were used in Coinman and Fox (2000) and Fox and Coinman (2000).

3 Reference to these core trimming elements was made in Coinman (1990:265) after observing them in assemblages from Abu Noshra, Ein Aqev, and Ein Aqev East. Subsequently, they were noted in other Ahmarian assemblages in the al-Hasa area and south Jordan (Coinman and Henry 1995:145). Most recently they were noted by the author on two refitted cores from Azariq XIII, a late Upper Palaeolithic/early Epipalaeolithic site in the western Negev, also classified as Masraqan (Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 1997). They are only half-crested with the ‘crest’ comprised of a portion of the lateral edge of the core’s platform. They were struck from the back of the core rather than the front face of the core, where a removal might include a front ridge(s) and ‘cresting’ representing distal trimming on the distal end of the core. The latter type of trimming element has been documented in the Early Ahmarian assemblage at Tor Sadaf and is included in the category of crested blades.

4 The ‘width’ of a platform represents a lateral measurement of the platform similar to the lateral width of a blank (side to side), while the ‘thickness’ is similar to that for a blank and is measured between the dorsal to ventral sides. Both measurements follow Ferring (1980:81), Dibble (1987:113), Andrefsky (1998:93), and Shott (1986:40) among others.