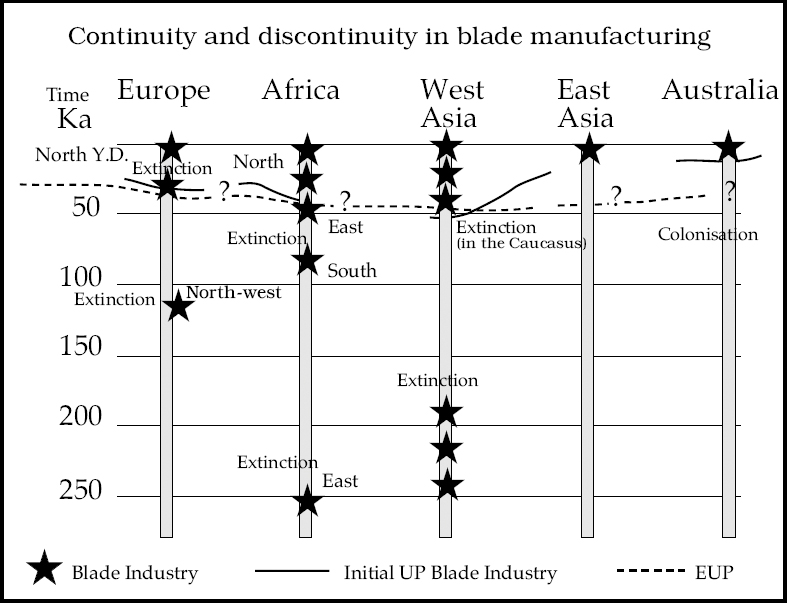

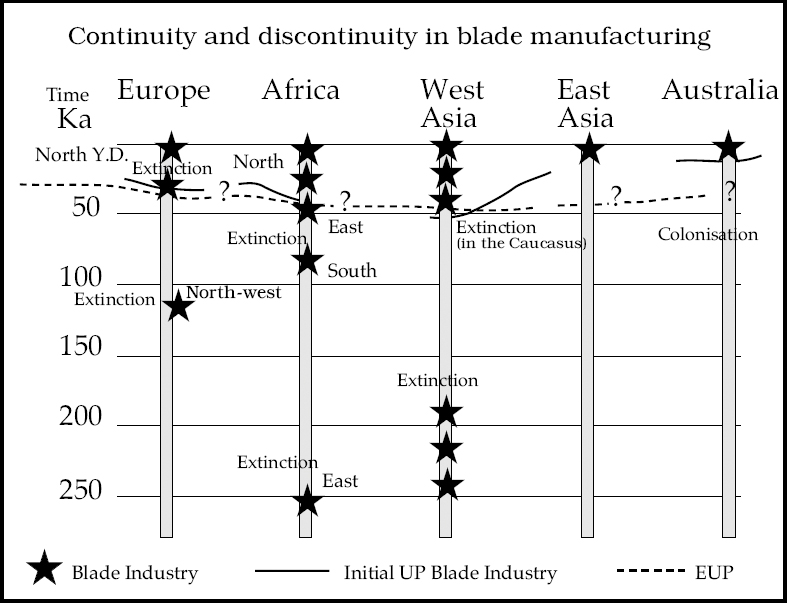

Fig. 22.1 Suggested population extinctions between different periods of blade manufacture.

The common goals of Palaeolithic archaeology are to address issues of stratigraphy, chronology, and cultural entities, beginning with the analysis of lithic and bone assemblages, and peaking with the coarse-grained paintings of prehistoric life ways. Within this framework, modern research stresses the necessity of conducting regional investigations aimed at establishing local sequences. This is what the papers in this volume are all about. The period under consideration is the Upper Palaeolithic, a term coined in western Europe, the homeland of our discipline. It seems to me that currently there is very little room for presenting additional data or discussing particularities. Rather, I would like to examine the Upper Palaeolithic phenomenon from a broader perspective. Adopting a wide-angle view may assist us in placing what is recorded and so well presented in this volume within a comprehensive, global scope.

The issues to be discussed below are those pertaining to questions such as:

(a)is the transition to the Upper Palaeolithic a major evolutionary event of global proportions;

(b)was the impetus for the transition to the Upper Palaeolithic a biological and/or cultural change;

(c)what could have been the meaning of the operational sequences (châines opératoires) within a particular time trajectory;

(d)what possible palaeodemographic implications derive from the studies of operational sequences in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic?

During the evolution of humankind we see specific times when economic, political and technological changes occurred rapidly. Although scholars disagree on the number of major cultural changes required to merit the label ‘revolution’, there is little doubt that the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic, the Neolithic transformation of foraging to farming, the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century, and the Communications Revolution of the 20th century should all be labelled as such.

We generally evaluate revolutions on the basis of their outcome. We can easily find, as in every scholarly debate, gradualists who would interpret the most dramatic cultural and socio-economic changes as slow incremental processes lasting hundreds or even thousands of years. Adherents to the idea of gradient change identify a long period during which certain elements (social, symbolic, technological and the like) accumulated, which, a posteriori, will be seen as ‘preparatory’ for the actual transition.

In contrast, scholars who view a major technological and or/socio-economic change as radical and rapid will focus more specifically on ‘when’ and ‘where’ it occurred. Successful completion of the first phase of such a critical transformation will culminate in ‘a point of no return’. The catalytic change or series of changes would often result in the emergence of new social and economic systems, leading expectedly to shifts in ideology. It is possible to observe how the re-designed belief systems accommodate the ‘new regime’. The ideological modifications are commonly initiated by powerful shamans, priests and, more recently, by political and religious leaders, and these modifications would find their expression first in public gatherings, and only later in the domestic arena, which is generally more conservative. As archaeologists we can evaluate and interpret each of these ‘revolutions’ only when their outcome is reflected in the material world, which may only occur a century or more after the socio-economic transformation.

The advantage of historical studies is that scholars can geographically and chronologically pinpoint when and where a revolution began. For instance, historical documents and archaeological remains record the ‘when’ and ‘where’ of the Industrial Revolution in 18th century England, how quickly technical inventions were transported to other regions, and when and how social changes occurred (e.g., Landes 1969, 1998; Wolf 1982; Goldstone in press). However, reaching agreement among historians and anthropologists concerning the ‘why’ question is more difficult, even in the case of the Industrial Revolution. The lesson for archaeologists who study the prehistoric past that leaves no trace of names for social units and their chiefs, is that the ‘when’ and ‘where’ should be our first concern, while answers to the ‘why’ question will remain elusive and open to constant debates and reinterpretations.

For example, it is difficult, in spite of the rapidly accumulating data, to be specific about the ‘when’ and the ‘where’ of the Neolithic Revolution during the Terminal Pleistocene-Early Holocene. Even when the time-scale is based on dendro-calibrated chronology, the error margins of the dates preclude reconstruction of historical events per se. Given the current level of knowledge, we must recognize the generic limitations of the archaeological records as well as the time determinations produced by the best laboratories.

The notion of ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ was borrowed from the study of historical periods, but used only as geographic definitions (Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1989). Innovations or inventions often appear first in a ‘core’ area and then spread elsewhere. However, the Lower Palaeolithic record provides some serious warnings against these assumptions. It is generally suggested that during the Lower and Middle Pleistocene, the longdistance human dispersals can be shown by the geographic distribution of a given lithic operational sequence (Rolland 1996, 1998). This notion is derived from the extrapolated evidence for the spread of early hominids across extensive landmasses over long time-spans. None of these movements, as the gaps in the archaeological records indicate, ensured the survival of the new immigrants or colonisers. Extinction of lineages and/or populations is recently being considered by archaeologists (e.g., Bar-Yosef 1998c; Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 2001), and is supported by the biological evidence for ‘bottlenecks’ (Harpending et al. 1998). Hence, if the biological continuity of human populations over large geographic distances and variable ecological zones cannot be demonstrated, we need to accept as a viable hypothesis that certain tool making techniques were invented independently at different times and different places during the Lower and Middle Pleistocene (Fig. 22.1). Such cases would be the independent inventions of the bifaces (e.g., Villa 2001) and the basic blade techniques (e.g., Bar-Yosef and Kuhn 1999). Nevertheless, it is possible that in the future, with further improvements in radiometric techniques, continuity in time and space during the late Middle Pleistocene and the Upper Pleistocene, of a particular lithic technique or way of shaping bone and antler objects may be recognized as reflecting the movements of people.

Indeed, the genetic evidence in Europe and the Mediterranean basin suggests long distance dispersals, thus the rapid spread of Homo sapiens sapiens is viewed as marking the onset of the Upper Palaeolithic. However, before discussing the regions that clearly display markers of the transition (Europe, northern Asia, and north Africa), and areas in which the transition is not well-recorded or simply did not occur (southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa), we need to enumerate the attributes of the Upper Palaeolithic revolution.

The literature is equivocal about the reasons we observe certain cultural and biological differences between the Middle and the Upper Palaeolithic. Generally, the currently available evidence is derived from Eurasia, with much less from Africa. On the whole, with some exceptions, Upper Palaeolithic contexts are characterized by the more or less consistent appearance of the following traits (e.g., White 1982; Gilman 1984; Klein 1995a, 1999).

a.Systematic production of prismatic blades with rare occurrences of entities where flake production is dominant.

b.Regional and relatively rapid shifts (within hundreds or a few thousand years) in artefact design, which are interpreted as reflecting stylistic variability.

c.Long-distance exchange networks of lithics and other raw materials ranging over several hundred kilometres.

d.Improved hunting tools such as spear-throwers, the eventual invention of bows and arrows, and boomerangs.

e.Clearer intra-site spatial organisation within habitations and hunting stations, determined by functional needs (storage facilities, kitchen area, sleeping grounds, and the like).

f.Systematic production of bone and antler artefacts for daily and ritual uses.

g.Systematic use of body decorations such as marine shells, tooth pendants, etc.

h.Mobile imagery (human and animal figurines), decorated and carved bone, antler, ivory and stone objects.

i.Representational and abstract images and signs, whether painted, engraved or both in caves and rockshelters, as well as on exposed rock surfaces.

This array of achievements reflects not only technological innovations but also the unique characteristics of each regional archaeological culture. Moreover, it is neatly demonstrated by the so-called ‘creative explosion’ that essentially denotes populations in western Europe, and in particular the Franco-Cantabrian interaction sphere (Bahn and Vertut 1988). In spite of the contemporaneity of Upper Palaeolithic artistic manifestations with other Homo sapiens sapiens populations, no similar florescence of rock art is found in other regions, including those with karstic caves where foragers survived for longer periods such as the western Caucasus (e.g., Liubin 1989).

We should keep in mind that some of these tools, techniques, and behaviours – often considered as characteristics of Homo sapiens sapiens – are known from various sites of Middle Palaeolithic age. For example a rich bone tool assemblage was uncovered in the Middle Stone Age Bloombos cave in South Africa (Henshilwood et al. 2001), or late Neanderthal contexts such as Arcy sur-Cure (Zilhão and d’Errico 1999). Red ochre was reported from numerous Middle Stone Age and Mousterian sites (McBrearty and Brooks 2000; Mellars 1996a, b; Henshilwood and Sealy 1997; Hovers 1997; Wreschner 1976). Intentional burials were practiced in Mousterian contexts in the Levant since the Last Interglacial (Belfer-Cohen and Hovers 1992). The point to be stressed is that several traits, such as blade production, selective collection of marine shells, and the making of bone tools, appear as irregular phenomena during the late Lower and Middle Palaeolithic (e.g., Moloney 1998). They became regular cultural components of the Initial Upper Palaeolithic, after ca. 45 ky (Kuhn and Stiner 2001; Ambrose 1998b).

Fig. 22.1 Suggested population extinctions between different periods of blade manufacture.

Explanations for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition have remained static during the last century and a half. Most prehistorians view the European sequence as the model, and the appearance of the Cro-Magnons as determining the fate of the Neanderthals. In recent decades, gradualists have suggested a smoother transition triggered by human adaptations to variable environments (e.g., Clark and Lindly 1989). Others, with the emerging evidence from genetic studies, have preferred full or partial replacement (e.g., Stringer and Gamble 1993). It was further suggested that modern Homo sapiens capacities are related to a neurological mutation some 50 ky ago (Klein 1995a). An additional matter to consider has been the discovery that the Chatelperronian (with bone tools, pendants, and blade industry), originally thought of as an Upper Palaeolithic entity, was probably produced by Neanderthals. It was suggested that this phenomenon resulted from a process of acculturation (Mellars 1989). Criticism of this interpretation was based on the fact that the radiocarbon dates, when placed on a geographic trajectory from east to west across Europe, do not support the idea of interaction between the incoming Cro-Magnons and the local late Neanderthals (Zilhão and d’Errico 1999). According to these scholars, the early Aurignacian dates which indicate the contemporaneity between the Chatelperronian and the Aurignacian should be rejected on the basis of careful analysis. Another view of the issue regards this transition as triggered by technological innovations and inventions in a particular core area, as with other revolutions (Bar-Yosef 1998a). The rivalry between the Neanderthals and the incoming Cro-Magnons is seen as competition between two populations (Bocquet-Appel and Demars 2000). The processes and results are described elsewhere (Bar-Yosef 2000). However, the debate on the causes for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition continues.

At the same time we are witnessing the further accumulation of data sets as additional sites are excavated across Eurasia (e.g., Derevianko et al. 2000). The colonisation of Australia, some 60 ky ago, was accompanied by but a few Upper Palaeolithic cultural traits (Thorne et al. 1999; Stringer 1999). In Tasmania, Upper Palaeolithic assemblages comprise simple core and flake industries, yet are supplemented by bone tools (Jones 1995). However, a more striking challenge to the Eurocentric model comes from two other regions – southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

We know that southeast Asia produced an entirely different Palaeolithic sequence than that in most of Eurasia and Africa. The lithic sequences of this vast region mostly reflect the production of core and flake assemblages, with only the rare appearance of Acheulian assemblages during the Lower/Middle Pleistocene (Huang and Wang 1995; Hou et al. 2000). The Upper Pleistocene core and flake industry is known in southeast Asia as the Hoabinian (Allchin 1966) and the only markers that indicate a change during the ‘Upper Palaeolithic’ are the bone tools which are missing from earlier contexts (e.g., MacNeish 1996). Overall, the cultural attributes of the Upper Palaeolithic in western and northern Eurasia as reflected in the stone, bone and antler industries are not found in southeast Asia. The geographic boundary between these two major cultural provinces is the Qinling range of mountains in China. This east-west chain separates the Yangzi River basin in the south from the northern Yellow River basin. It is only in the latter that microblade industries, which spread from western Asia through Siberia and later into the New World, are well-documented (Olsen 1987; Chun and Xiang-Qian 1989; Goebel et al. 2000; Brantingham et al. 2001; Lu 1998). We may therefore be puzzled by the genetic evidence, which indicates a more or less Upper Palaeolithic age for the Chinese population as a whole (Piazza 1998). Does this mean that present-day Chinese populations derive solely from Upper Palaeolithic groups inhabiting northern China?

The idea that the tropical zone, such as southern China, is an optimal ecological niche for stragglers, relict species that survive there beyond other members of their genus, is not foreign to prehistoric research. For example, the suggested late dates for Homo erectus in Indonesia and their apparent contemporaneity with archaic modern humans, is well known (Swisher et al. 1996). Similarly, the survival of populations in mountainous areas is documented by cases of late Neanderthals in Iberia, the Caucasus and Crimea (Bar-Yosef and Pilbeam 2000). On the whole, the contemporaneity between different Palaeolithic entities or ‘cultures’ is a worldwide phenomenon. In several cases, the bearers of one culture could have been more aggressive and successful than their neighbours. Competition over resources could have led to the extinction of particular populations. Only further research in southeast Asia may clarify the socio-economic processes and their ecological contexts, which encouraged the conservatism in the manufacture of stone tools as a most advantageous strategy during local Upper Palaeolithic times.

A different picture emerges in Africa. The current survey of the sub-Saharan Middle and Upper Palaeolithic (known locally as Middle Stone Age (MSA) and Late Stone Age (LSA) suggests that there is no evidence for an Upper Palaeolithic ‘revolution’, such as that conceived in Europe, western and northern Asia (e.g., Deacon and Deacon 1999; McBrearty and Brooks 2000). This claim is essentially based on the gradual appearance of various Upper Palaeolithic markers across Africa (McBrearty and Brooks 2000). In particular, McBrearty and Brooks stress the early manifestation of bone tools, use of red ochre, appearance of beads and the like. The limited geographic distribution of cave art and its absence from regions such as north Africa, the Near East or Siberia, has not hindered the attribution of archaeological contexts to the Upper Palaeolithic. Interestingly, most of these modern behavioural attributes already appear in Africa during the ‘Last Interglacial’. Assigning ages in the range of 150/130 ky for the gradual accumulation of modern behavioural expressions concurs with those indicated by nuclear and molecular genetic data for the emergence of modern humans (Harpending et al. 1998; Underhill et al. 2001). Without delving into the issue of biological evolution, the processes described by McBrearty and Brooks, mainly from sub-Saharan Africa, support the notion of a long ‘brewing’ interval needed by Modern Humans to prepare for the Upper Palaeolithic Revolution (Bar-Yosef 1998a).

One major point stressed by scholars relates to the kind and type of stone tools made by humans. During the timespan known as the Initial Upper Palaeolithic, lithic assemblages underwent either major or minor changes (depending on the researcher’s preferred paradigms). Hence, it would be seem appropriate to examine the ways in which we study and interpret stone artefacts.

The search, either explicit or implicit, into the minds of prehistoric knappers seems today as one of the most informative and meaningful ways of conducting lithic analysis. The concept was derived from the work of Leroi-Gourhan (Audouze 1999), studies by R. Cresswell (1982, 1992), and others (such as P. Lemonnier 1992), and were integrated by French prehistorians’ lithic analysis (e.g., Pigeot 1990, 1991; Boëda 1988b, 1995a; Boëda et al. 1990; Géneste 1985; Sellet 1993; Inizan et al. 1999). This method of analysing lithic assemblages, whether based on refitting or simple ‘reading’ of the scar patterns, was adopted by others elsewhere in Europe and the Near East (Van Peer 1992, 1995; Bar-Yosef and Meignen 1992; Meignen 1995, 1998b; Sellet 1995; Schlanger 1995b; Kerry 2000). However, the best way to study the sequence of knapping decisions executed by the prehistoric knapper is to analyse each step apparent in a refitted core (e.g. Volkman 1983; Goring-Morris et al. 1998; Schlanger 1995b). The desired blanks, identified by the archaeologist, are those that bear secondary modification (by retouch) or signs of utilisation revealed through microwear analysis. These blanks reflect the initial aims of the artisan and his/her decision as to which blanks are the appropriate pieces for use.

Studying and classifying the operational sequences, when refitting was not conducted due to lack of funds, incompleteness of the studied assemblage, or simply due to the condition of the artefacts, is not an easy task. Frequently, researchers attribute considerable importance to the study of the discarded cores. However, the scar patterns of an exhausted core, when compared with the primary post-decortication blanks, reflect changes in the sequence of the knapper’s actions. For example, it may happen that a ‘unidirectional recurrent Levallois core’ was modified into a ‘centripetal’ (also called a ‘radial’) one in its final stages of exploitation. Another example would be blade cores known as ‘crossed’, changed orientation or ‘at ninety degrees’, when one surface from which blades were removed is perpendicular to the second surface.

The trouble with drawing conclusions from the discarded cores is that it is impossible to know whether the change in the procedure for flake or blade removals was implemented by the original knapper or by someone else. Identifying the individual knapper is a problem that is rarely addressed (though see Ploux 1991). Often, archaeologists assume that the same knapper used a particular core from the beginning to its final, exhausted stage, as seen today in the archaeological record. However, this assumption is not warranted. We need, in the course of investigating a lithic assemblage, to ask ourselves who was responsible for the exploitation of the discarded cores. I am fully aware that this is not an easy question to answer. One way of testing the option that more than one person was involved in the process of core reduction is when the evidence for the use of the core comes from refitted blanks that were collected from two or more spatially separated concentrations. Faced with this kind of evidence we may conclude that either a single individual carried out spatially and temporally different knapping sessions, or that different knappers used the same core during its life history. It is appropriate, in this context, to raise the possibility that before cores became fully exhausted they may have been used in practice sessions, when one knapper taught another, in particular while teaching younger members of the group. Additionally, imitators such as small children playing games could have picked up the discarded cores or thick flakes that adult knappers would consider to be unusable, and practice without supervision.

In sum, given the degree of intra-site and/or intraassemblage variability, the identification of the châine opératoire should, in my view, be based solely on the first series of blanks removed. I suggest assigning only secondary value, if at all, to the categorisation of the discarded cores. The final forms of the cores should be regarded as simple cases of equifinality, unless they conform to the original design of blank reduction. For example, the proliferation of centripetal scar patterns on discarded cores in an assemblage where most larger and primary blanks indicate ‘recurrent Levallois’ may simply mean that the cores were used for teaching or for the expedient extraction of small flakes. A similar example, as mentioned above, among Upper Palaeolithic assemblages, is when prismatic cores become in their final phase (sometimes after a change in the direction of blade removals to create those types known as ‘crossed striking platforms’ or ‘at 90 degrees’) a source for small flakes or bladelets (e.g., Bar-Yosef and Belfer 1977).

Studies of the châine opératoire in every prehistoric period also should be required to address two crucial issues: (1) What meaning can we derive from essentially the same châine opératoire being employed for extended periods on the order of 40–50,000 years and even more (e.g., Bar-Yosef 2000)? And (2) why, if that châine opératoire is optimal, do we suddenly witness change? Each of these questions is exemplified by several archaeological cases, beginning with the late Middle Palaeolithic.

The documented châines opératoires of Levantine Middle Palaeolithic assemblages served, until recently, as the basis for clustering assemblages into industrial groups (e.g., Bar-Yosef and Meignen 1992; Meignen 1995; Meignen and Bar-Yosef 1991). This is not to say, as stressed elsewhere (Bar-Yosef 1998b, 2000) that some variability does not exist between these Mousterian assemblages. The remarkable similarity of assemblages, such as Tabun B, Geula, Kebara, Amud, and Tor Faraj was noted and the assemblages were clustered under the temporary term ‘Tabun B-type’ industry (Bar-Yosef 2000). One example of minor changes is the difference between units XII–IX and VII–VIII in Kebara. The frequencies of blades increase and the triangular Levallois points decrease in the upper units (Meignen and Bar-Yosef 1991; Meignen et al. 1998). However, through the entire sequence the ‘convergent recurrent Levallois method’ remains the dominant method of obtaining blanks. Similar cases are documented in the course of comparisons between Amud, Tor Faraj, and Kebara (e.g., Henry 1995d, 1998; Hovers 1998).

The trouble is that the sources of the observable variability are not easily explained. It is possible that the ‘devil is in the details’, but what does it mean? We do not have the terms of reference that are required in order to provide a palaeo-anthropological interpretation for the observed variability. Under these circumstances the most parsimonious explanation, in my view, is the one suggested above, namely that the variability was the expression of the individual abilities and capacities within a given, rather rigid system of teaching. The common opinion among researchers of Middle Palaeolithic assemblages is that the prehistoric knappers had comprehensive knowledge of all of the available methods and techniques. Following this argument, knappers must have made choices about tools as they enjoyed or suffered living in different environments. As a reminder for the researcher, the large body of Middle Palaeolithic technical information incorporates the various Levallois and non-Levallois methods as described and defined by Boëda and others (Boëda et al. 1990; Boëda 1995a; Van Peer 1992). The assumption that Middle Palaeolithic knappers mastered this entire array of Levallois and non-Levallois techniques remains unproven. Unfortunately, the specific ‘life histories’ of refitted cores or the reconstructed châines opératoires, cannot be attributed to particular individuals. Our desire to trace the role of the human agent is legitimate, yet the task seems to be more facile to achieve under ‘Pompei premise’ conditions (Binford 1981), i.e., in sites where living floors were covered soon after abandonment. However, when ‘living floors’ accumulate and create a palimpsest, as demonstrated by the thick accumulations exposed in the Levantine caves, the clustered assemblages represent long-term tendencies in the use of one particular (rarely two) methods of knapping.

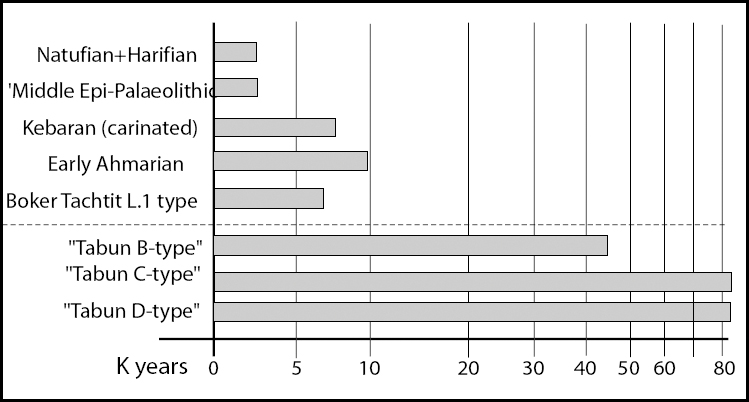

I have mentioned elsewhere the variable rates of deposition in sites such as Kebara and Hayonim caves (Bar-Yosef 1998b, 2000). In Kebara, one cubic metre produced 1,000 or more pieces (longer than 2.5 cm) accumulated over ca. 3,000 TL years. In Hayonim, the same volume with 300 or less pieces accumulated during ca. 10,000 TL years. At Kebara the rare microfauna indicate a more or less constant human presence and thus the almost complete absence of barn owls, in contrast to the reverse situation at Hayonim. The interpretation, besides differences in relative group mobilities and thus in settlement patterns, as well as demographic densities (Stiner et al. 1999; Hovers 2001), is that the same one or two châines opératoires were practiced for a very long time (Meignen 1995, 1998b). Hence we may conclude that rigid teaching and transfer of knowledge within a closed society persisted over the course of many generations among Middle Palaeolithic groups. This picture differs markedly when we examine Upper Palaeolithic contexts and industries across Europe, western and northern Asia and North Africa (Fig. 22.2).

In the course of changing approaches towards lithic analysis during the last two or three decades, I believe the significance of the retouched pieces, traditionally called ‘tools’ receded and sometimes was even ignored. Studies of operational sequences focus primarily on the blanks that were selected for use, and no special attention is given to secondary retouch. Yet, classification of retouched pieces is a critical aspect of archaeological investigation and, at least during the Upper Palaeolithic, it clearly demonstrates that, while the châine opératoire changes very slowly through time, shifts in tool forms are more rapid (e.g., Goring-Morris et al. 1998).

On this issue a brief historical reminder is necessary. Abbé H. Breuil was the scholar who in 1913 published the first synthesis of the Western European Upper Palaeolithic. His scheme, which left an indelible terminological impact, was based on the stratigraphy of French sites and differences in tool types (Breuil 1913). The earliest, immediately post-Mousterian entity, with Chatelperronian knives, was named ‘Lower Aurignacian’ followed by ‘Middle Aurignacian’ and ‘Upper Aurignacian’ with Gravettian points. The later entities were the Solutrean and the Magdalenian. In the 1930s, D. Peyrony, a local enthusiastic prehistorian in the Perigord, suggested renaming the ‘Early Aurignacian’ and the ‘Late Aurignacian’ as Perigordian I–V, because they were all blade dominated assemblages with backed points. In the English language literature the ‘Early Aurignacian’ was called the ‘Chatelperronian’ (today also known as ‘Castelperronian’) due to the presence of curved backed Chatelperronian knives (Bordes 1968b). The ‘Middle Aurignacian’ retained the appellation of the ‘Aurignacian Culture’, characterised by carinated and nosed scrapers and a rich bone and antler industry. The ‘Late Aurignacian’ was called Perigordian IV by Peyrony, but the term ‘Gravettian’, after the straight-backed Gravette points, finally gained acceptance (e.g., Coles and Higgs 1969). The scheme of Peyrony, except for the separation of the Aurignacian into a different culture or cultural tradition, did not survive the introduction of radiometric dating and re-analysis of the local lithic assemblages in western Europe. A return to the basic definitions of independent entities is accepted as the rule of the day (e.g., Gamble 1986; Collins 1986; Djindjian et al. 1999).

Only one notion has remained deeply embedded in the literature, namely that the Chatelperronian is an Upper Palaeolithic entity representing the cultural ‘transition’ from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic. As predicted by F. Bordes (1972), although he himself had difficulties accepting the corresponding biological implications, the Chatelperronian had its roots in the late Mousterian of Acheulian Tradition, which according to the fossil record was the creation of local Neanderthals. The discovery of Neanderthal remains in a Chatelperronian layer in St. Césaire provided the hard evidence for biological continuity accompanied by cultural change amongst a single population (Lévêque and Vandermeersch 1981). Indeed, the Upper Palaeolithic traits of the Chatelperronian (the production of blades and curved backed blades) which were documented by J. Pelegrin (Pelegrin 1990a, b; Lévêque et al. 1993), are instructive: a) the term ‘transitional industry’ can have biological as well as cultural implications; and b) the blades per se cannot serve as the sole marker for designation of the ‘Upper Palaeolithic’ (e.g., Bar-Yosef and Kuhn 1999).

The case of the French Chatelperronian, which can be matched by examples from other geographic regions, raises the question ‘what is the Upper Palaeolithic?’ Take, for example, the Howieson’s Poort industry in South Africa (e.g., Deacon 1992, 1996; Deacon and Deacon 1999; Wurz 1996, Henshilwood et al. 2001). This is a blade industry, currently dated to ca. 80–60 Ky, with a dominance of crescentic backed blade forms and bone tools, intercalated within the Middle Stone Age sequence (e.g., d’Errico et al. 2001). Another example is the Szeletian and the Bohunician cultures in Central Europe, which are considered ‘transitional industries.’ The first did not produce evidence that it developed into a fully-fledged Upper Palaeolithic entity (Kozlowski 2000), while the second did not develop out of a local Mousterian, but rather is now considered intrusive into this region (e.g., Svoboda and Skrdla 1995; Tostevin 2000).

Fig. 22.2 Approximate duration of various châines opératoires in the Levant based on Bar-Yosef 1998b, and Goring-Morris et al. 1998. Note that the approximate duration is longer for the Middle Palaeolithic and shorter for the Upper Palaeolithic. Sometimes more than one châine opératoire was practiced in the course of any interval (Meignen 1995, 1998b).

It is therefore best to abandon the term ‘transitional industry’, which we have extensively employed over the last five decades, and call Early or Initial Upper Palaeolithic (Marks 1990) entities by local names. We can refer to an entity as ‘transitional’ only when it is demonstrated that the described assemblage represents a local cultural transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic. Otherwise, as shown by the above-mentioned cases, an industry with ‘transitional’ characteristics may rather represent processes that initially took place elsewhere. For a foreign group to establish itself in a new environment there was a need for techniques to exploit local resources, possibly with minimal or no conflict with local populations. During the Stone Age there were undoubtedly empty regions with adequate subsistence resources. The absence of people from such areas could result from stochastic dispersals as well as local extinction (through natural or violent means).

The study and interpretation of retouched pieces is no less important than the analysis of core reduction strategies. One may argue that the different forms are generally related to function and possibly influenced by the nature of available raw materials. Thirty years of microwear and edge damage studies have demonstrated that the above are not the reasons for assemblage variability during the Palaeolithic (e.g., Beyries 1988, 1993; Jensen et al. 1991). The need for suitable sharp or blunt edges for cutting, whittling, butchering, engraving, and perforating, created the need for variable design of retouched pieces such as scrapers, burins, backed knives and the like. It seems to me that the correlation between function and form is very weak, in spite of previous expectations. If this contention is accepted, then retouched pieces during the Upper Palaeolithic owe their forms more to style than to function. Thus, contemporary foragers, whether they encountered a foreign group bearing their equipment or just found their discarded or deserted stone tools, could easily detect the presence of ‘others’. Stylistic variability then becomes the means for marking group identities. As such their attributes deserve to be investigated, and employed in reconstructing ‘life histories’ of particular prehistoric populations. In this domain of research, hafting, or the production of composite tools, should be mentioned. An excellent example concerns the various types of projectiles produced during the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic that served as tips for spears and arrows (e.g., Bergman and Newcomer 1983; Bergman et al. 1988; Knecht 1997 and papers therein; Shea et al. 2001). Various, but not all Upper and Epipalaeolithic microlith types fall in the same category and were hafted as arrowheads and barbs. The differences in shapes of the latter types and the details of their hafting techniques in the circum-Mediterranean area, had no bearing on the type and size of the hunted animals. Instead their variable forms reflect local styles. In a most generalizing observation, I would state that the shift in design, when suitability for function overrides style, is better expressed during the Neolithic period. Tool types such as sickle blades, perforators, adzes and axes and arrowheads, were shaped with a particular activity in mind. Accidentally, some tools could have been used for other purposes, such as arrowheads employed in butchering (e.g., Moss 1983).

Population growth in foraging as well as sedentary societies is thought to trigger cultural changes. Population increases have major implications, no less than population decreases that may have led to extinctions. Naturally, aspects of mobility, technology, and the distribution of resources are implicitly and explicitly embedded in explaining increases in producers and consumers. But how are these issues related to our topic?

The châine opératoire, as discussed above, is basically a system of technical skills learned by the user, and does not necessarily imply the use of language (although talking while knapping helps). On the basis of ethnographic observations, the châine opératoire employed in manufacturing a given product from a particular raw material represents the technical traditions of a specific group. The teaching of this skill through instructional sessions ensures the transmission of this knowledge from one generation to the next. Therefore, the time span during which a certain châine opératoire was practiced could indicate how long a particular technical tradition lasted. Typological analysis is likely to bolster this conclusion. Demonstrable stability of both aspects despite climatic fluctuations, when the spatial distributions of resources would be highly affected, indicates that changes in technical modes and tool types are not strictly related to environmental conditions.

This kind of information raises the issue of the biological and/or linguistic continuity of specific populations within a given region. Radiometric dates provide temporal depth, enabling us to identify the history of a social group or close kin interaction sphere. Effectively, this approach of combining châine opératoire and typological studies has already been employed by archaeologists studying Middle and Upper Palaeolithic assemblages.

Using the information obtained from studies of châine opératoire and tool typology as a common denominator, we gather the data required for inter-assemblage comparisons. Some researchers view the châine opératoire as a purely descriptive procedure and not as a valid palaeo-anthropological measure facilitating the clustering of assemblages into industries. However, such an approach reduces the value of this analytical tool for identifying real past populations.

Indeed, during the Middle Palaeolithic the persistence of particular Chaînes Opératoires has a long duration. We may therefore assume that they represent a single biological population, and even the same linguistic tradition that facilitated the transmission of the cognitive model of the knapping method through teaching (Mithen 1995). It is also conceivable that population size expanded and shrank, by absorbing neighbouring groups, or losing members through extinction. Perhaps, given the possible fluidity of these Middle Palaeolithic societies, we should view them as early ‘interaction spheres’ rather than some sort of ‘tribal’ society or an agglomeration of bands.

The Upper Palaeolithic populations of Eurasia demonstrate increasingly successful adaptations to environmental changes, and in particular to demographic fluctuations (Kuhn and Stiner 2001). Courage and adventurous spirits led certain populations to cross the ‘northern boundary’ and adapt to arctic conditions, while others experimented with coastal ocean sailing which brought about the colonisation of Australia and adjacent islands (Blust 1995; Rolett et al. 1998; Stringer 1999). After the Last Glacial Maximum desertic regions, which had previously been abandoned during drier periods, were permanently occupied by foragers.

Indeed, Upper Palaeolithic entities exhibit the same demographic ‘life histories’ as those known from later historical periods. They comprise phases of emergence, effloresence, long periods of success, ensuing stalemate, and final collapse (Goldstone in press). Discussion of particular examples is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that similar processes can be detected in the dramatic changes that occurred during the Levantine Epipalaeolithic. We may regard the rise and fall of the Natufian culture as an example of how successful economic and social organisations resulted in the emergence of a complex society of hunter-gatherers, which ultimately, except for certain groups within its large population, collapsed in response to the vagaries of the Younger Dryas cold and dry period.

The ‘life histories’ of Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic entities can be viewed not only through their châines opératoires, but also through site organisation, changes in food acquisition techniques (the Broad Spectrum Revolution – see Flannery 1969; Stiner 1999b), exploitation of variable environments, and social reorganisation. However, as this paper essentially concentrates on the lithic aspects of the Upper Palaeolithic, the treatment of these issues is offered.

A good example for changes in lithic industries is provided by studies conducted by Goring-Morris and associates (Goring-Morris et al. 1998). Core refitting of a series of Epipalaeolithic assemblages demonstrated how the same knapping techniques prevail while the style of the retouched pieces changed. There is no evidence that the latter developments reflect adaptations to shifts in the quality, distribution and accessibility of food resources. There is no evidence to date that food acquisition techniques, such as improvements in the construction of bows and traps, played a major role in typological changes in microliths. The most parsimonious explanation is that the different types of microliths designate different human groups, an explanation supported in part by the continuous geographic distribution of entities such as the Geometric Kebaran, Mushabian, Ramonian (or Late Mushabian), Natufian, Harifian, and the like. The manufacture of particular types of microliths and points by each entity may indicate the preservation of particular mating systems, especially in the drier belt, as well as the use of the same language or dialect. The exploitation of the same core reduction strategies may testify to an enduring traditional unity, or the existence of some sort of interaction spheres. Given the limited geographic territory of these entities, we may speculate that their physical and linguistic boundaries were more clearly delineated than those of the Middle Palaeolithic (Close 2000). When compared to the earlier portion of the Upper Palaeolithic time span, the increasing spatial and chronological variability of the Epipalaeolithic reflects a major population increase following the LGM, and the opening-up of desertic environments for exploitation by highly mobile foragers. The situation in the southern Levant, known from extensive fieldwork in this area (contra the paucity and rarity of information from the northern Levant) may resemble the variability of recent demographic densities in New Guinea (Blanton 1995).

Almost since the beginning of the 20th century, scholars have worried about the definition of archaeological entities as uncovered in excavations and surveys. Needless to mention the work of G. Kossima, G. Childe, D. Clarke and more recent critics who warn, justifiably, that prehistoric cultures cannot be directly equated with historical cultures (e.g., Jones 1997). Nevertheless classification is a necessary device for arranging data. Using Celsius or Fahrenheit for measuring temperature does not have any bearing on the actual condition. The continued use of these two scales represents no more than cultural customs, habits, or even transmitted concepts. In considering tomorrow’s temperature and, therefore, which clothes should be worn we decide according to our relative feeling of cold or warm. Acquisition of the concept represented by the measuring scale, which in this case is translated into a physical feeling, is primarily a matter of habituation from a young age. The same is valid for how one makes stone tools and the same would hold for how one defines prehistoric entities.

The various definitions assigned to assemblages do not lend themselves to a fully objective interpretation. Every prehistorian knows that when we mention the Mousterian the connotation involves a certain set of artefacts. Similar images emerge when definitions such as the Szeletian, the Bohunician, the Natufian and others are invoked, whether in oral or published reports. The social and historical meanings remain to be discussed by the interested parties. Hence basic classifications, although not always with agreed-upon scales as those employed for measuring temperatures, but incorporating categories with set combinations of attributes, are bare necessities. The systematic efforts of F. Bordes (1961a), D. de Sonneville-Bordes (1953), F. Hours (1974), and others, as well as more recently those of M. Bisson (2000) focused on this goal. Not always have these approaches included the concepts and the descriptive attributes of the techniques or methods through which the blanks were obtained. However, for now we are endowed with the works of Tixier (1963), Boëda (1995a), Meignen (1995), and Kuhn (1995) to mention just a few, and the importance of these studies of variable core reduction strategies cannot be over-emphasized, as shown by Dibble (1995b).

The same is true for the typological aspects of a given assemblage. Continuous modification processes of the so-called tools are well known (Keeley 1982; Dibble 1987), but the description of the lithic assemblages is done according to formal classifications, although one should be careful about their ‘cultural’ attributions. An excellent example is how Upper Palaeolithic Levantine assemblages have been incorporated or rejected from the taxon of the Levantine Aurignacian. In the final analysis, the Aurignacian needs to be defined on the basis of the original definitions. Variants do exist and should be taken into account, and yet, the endless expansion of the original definition, as was recently done (Kozlowski and Otte 2000) is unwarranted, for it only adds to the general ambiguity of defining the Aurignacian. In addition, lithic assemblages are all too often attributed to biological entities and not only by archaeologists. Biologists participate in the same game of equating haplo-type groups with prehistoric industries (Gibbons 2000; Semino et al. 2000).

In sum, returning to the questions asked in the opening remarks of this paper it does seem that at least in the Eurasiatic world, and probably in east and northeast Africa, the Upper Palaeolithic Revolution is well registered in the prehistoric record. Whether it all started due to an additional biological change among modern humans, or due to a technological transition that brought about the ensuing economic and in particular social changes, is still a debated issue. This revolution, like others, began in a ‘core area’ and dispersed, mainly through the movements of foragers who carried new equipment and especially new means for communication. Large-scale geographic distribution did not seem to interrupt the success of the mating systems in most regions. Faster changes (relatively to the Middle Palaeolithic) of operational sequences, and shifts in retouched tool morphology, together with the list of cultural attributes mentioned earlier, reflect flexible social systems, and rapidly increasing populations. The ‘bottleneck’ caused by the LGM, only slowed down the process of taking over new territories. It was immediately renewed as the glaciers began to melt. Therefore, the stone making traditions of the latest part of the Upper Palaeolithic, or Epipalaeolithic, present a variable set of retouched pieces, mostly microlithic, definitely more elaborate than during the earlier millennia. The accomplishments of the Upper Palaeolithic, and in particular the Levantine Epipalaeolithic created economically and socially the background on which the Neolithic Revolution could have taken place.