Chapter 14

Studying the Structure of Language

In This Chapter

Chatting about word use

Chatting about word use

Playing with sentences

Playing with sentences

Telling stories

Telling stories

Sophisticated, subtle communication is unique to people. Although many animals pass information between each other, no other species comes close to having a language system as complex as that of humans.

Language contains layers within layers of different structural levels. In this chapter, we look at these layers – from the smallest units to long stories, via words, phrases and sentences – and how people use them to build infinitely varied and complex messages to transmit information from one brain to another. We also describe some of the ingenious experimental designs that cognitive psychologists have used to investigate the ways in which people’s brains process language, as well as some of these tests’ intriguing findings.

Psychologists still have much to discover about how the brain processes language, but cognitive psychology reveals many surprising findings about these normally hidden mechanisms. Perhaps the most exciting discovery is just how much goes on in your brain in your everyday use of language.

Staring at the Smallest Language Units

Cognitive psychologists have been active in studying all the structural levels of language – how people piece together a sequence of processes that unfold as they listen to or read language.

Here are the two smallest parts of language:

Here are the two smallest parts of language:

- Phoneme: The smallest unit of speech sound that can change the meaning of a word. For example, ‘cat’ and ‘bat’ differ only in their first phoneme, ‘bat’ and ‘bet’ differ in their middle phoneme and ‘bat’ and ‘bag’ differ in their final phoneme. Although in these examples each word had three letters and three phonemes, you don’t always get such a nice, neat correspondence between letters and phonemes: for example, ‘be’ and ‘bee’ have two phonemes.

- Morpheme: The smallest part of a word that has a separate or distinct meaning. For example, ‘unbelievable’ contains three morphemes: ‘un-’, ‘believe’ and ‘-able’. ‘Dog’ and ‘elephant’ are each a single morpheme, but ‘elephants’ is two morphemes: ‘elephant’ and ‘-s’.

The basic letters or phonemes combine to produce morphemes, which combine to make words, which combine to make phrases, which combine to make sentences, which combine to make stories. At each level, complex and specific processes take place below conscious awareness.

Working with Words

Words seem to have a life of their own – they come in and out of fashion and change their meanings over time. These changes can be historical, but other changes occur as new words enter the language and others undergo changes in their use. Sometimes a word’s history can reveal something about how words interact with brains and the processes that shape language change.

In this chapter, we explore how new words are created within a language (morphology) and the rules that govern this process of reinventing language. People can invent new words by applying new prefixes (bits of words at the start, signified by a ‘-’ after them, for example, ‘bi-’) and suffixes (bits of words at the end, signified by a ‘-’ before them, for example, ‘-ing’). Whole new words can also be created but only of certain categories.

Morphing language: Fanflippingtastic!

Morphology looks at how people build new words out of old ones. But even though people can play with language, they don’t do so in a random way.

Morphology looks at how people build new words out of old ones. But even though people can play with language, they don’t do so in a random way.

Usually, people play with language in a consistent way. A basic example of morphing language comes from adding the ‘-s’ to words in English to make a plural. Therefore, if a new concept or thing is created (say that newfangled device replacing the typewriter: the computer), you know, without being told, that adding the ‘-s’ to the end means more than one computer. Creating new words clearly follows rules.

In 2011, US politician Sarah Palin’s emails were made publicly available. Some media reports mentioned her use of the word ‘unflippingbelievable’, where she inserted the mild expletive ‘flipping’ into the word ‘unbelievable’ to create a new word. Interestingly, when people do this kind of thing they always tend to agree on where the word should be inserted. So if you do feel the need to insert ‘flipping’ into ‘fantastic’, you’ll tend to say ‘fan-flipping-tastic’ and not ‘fantas-flipping-tic’.

In 2011, US politician Sarah Palin’s emails were made publicly available. Some media reports mentioned her use of the word ‘unflippingbelievable’, where she inserted the mild expletive ‘flipping’ into the word ‘unbelievable’ to create a new word. Interestingly, when people do this kind of thing they always tend to agree on where the word should be inserted. So if you do feel the need to insert ‘flipping’ into ‘fantastic’, you’ll tend to say ‘fan-flipping-tastic’ and not ‘fantas-flipping-tic’.

Types of morphology

While writing this chapter, a friend used the word ‘Berlusconified’ (based on Italian businessman and convicted criminal Silvio Berlusconi). We hoped that it would be a completely new word. But we were disappointed: the word occurred eight times on a Google search. Even so, that’s still fairly rare.

People alter words using morphology in two basic ways:

People alter words using morphology in two basic ways:

- Inflectional morphology: The way people modify words in certain standard ways to indicate things such as tense or number. For example, ‘dog’, ‘dog-s’; ‘cat’, ‘cat-s’; ‘jump’, ‘jump-ed’ or ‘jump-ing’; and ‘fMRI’, ‘fMRIing’ (just to try and invent a new word for using fMRI; see Chapter 1!).

- Derivational morphology: When people create a new type of word, such as taking a name (Berlusconi) and creating new words: ‘Berlusconic’, ‘Berlusconified’ and ‘Berlusconification’.

Although certain rules guide the morphology of words, not all words follow them. Although you can say ‘jump’, ‘jumping’, ‘jumped’ and ‘open’, ‘opening’, ‘opened’, you run into problems with ‘go’, ‘going’, ‘*goed’ or ‘run’, ‘running’, ‘*runned’: some words (exception words, highlighted with the ‘*’) don’t follow the normal rules.

Although certain rules guide the morphology of words, not all words follow them. Although you can say ‘jump’, ‘jumping’, ‘jumped’ and ‘open’, ‘opening’, ‘opened’, you run into problems with ‘go’, ‘going’, ‘*goed’ or ‘run’, ‘running’, ‘*runned’: some words (exception words, highlighted with the ‘*’) don’t follow the normal rules.

Creative morphology: The Wug Test

Although grammatical rules govern how new words are created, sometimes aesthetic reasons apply as well. Children use the same rules as adults in creating new words.

In 1958, Jean Berko Gleason published the results of an experiment in which she tested children’s ability to use morphology correctly. She showed them a picture of a made-up creature with a made-up name and the caption ‘This is a wug’. Then she showed them a picture of two of the creatures and said ‘Now there is another one. There are two of them. There are two.’ She waited for them to complete the sentence. Interestingly most children correctly said ‘wugs’, even though they’d heard only ‘wug’ before.

You see this kind of creative morphology at work in the mistaken use in words such as ‘shopaholic’ or ‘chocaholic’, derived from the word ‘alcoholic’. The correct morphology is just ‘alcohol’ plus the suffix ‘-ic’. But people use the last two syllables ‘-holic’ as a suffix meaning ‘addicted to’. Saying ‘chocaholic’ rather than ‘chocolatic’ seems more natural, even though the latter is more like the word ‘alcohol-ic’.

You see this kind of creative morphology at work in the mistaken use in words such as ‘shopaholic’ or ‘chocaholic’, derived from the word ‘alcoholic’. The correct morphology is just ‘alcohol’ plus the suffix ‘-ic’. But people use the last two syllables ‘-holic’ as a suffix meaning ‘addicted to’. Saying ‘chocaholic’ rather than ‘chocolatic’ seems more natural, even though the latter is more like the word ‘alcohol-ic’.

Inventing and accepting new words

The linguist Ferdinand de Saussure argued that words are arbitrary symbols (except for some words in languages based on glyphs, such as ancient Egyptian and Japanese): if you didn’t know the English word for ‘dog’, you wouldn’t be able to work it out by studying dogs. The English word ‘dog’ is no more or less appropriate than the word in French (‘chien’), in German (‘hund’), Turkish (‘kopek’), Welsh (‘ci’) or in any other language.

If most words can’t be guessed, no shortcut exists to learning the basic vocabulary of a language. But morphology and syntax (for more on syntax, check out the later ‘Seeing What Sentences Can Do’ section) allow you to combine those words to create a new meaning not heard before.

If most words can’t be guessed, no shortcut exists to learning the basic vocabulary of a language. But morphology and syntax (for more on syntax, check out the later ‘Seeing What Sentences Can Do’ section) allow you to combine those words to create a new meaning not heard before.

We draw a basic distinction between open- and closed-class words:

- Open-class words: Include nouns, verbs and adjectives. They’re open classes because you can create new ones. For example, the invention of the fax machine brought the words ‘fax’, ‘faxed’ and ‘faxing’ with it. When people invent a new concept, language allows them to add new words to describe it.

-

Closed-class words: A much smaller class that plays a functional role in language, including determiners (such as ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’), prepositions (such as ‘to’, ‘by’, ‘with’), pronouns (such as ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘you’) and possessive pronouns (such as ‘his’, ‘hers’, ‘its’).

Generally, you can’t simply add to closed-class words at will. For example, people have made various attempts to introduce gender-neutral possessive pronouns into English to help avoid gender bias – proposing invented alternatives, such as ‘Ey’ ‘Hu’ and ‘Peh’, instead of ‘he’ and ‘she’. These attempts largely failed, not necessarily for political reasons, but because of the way language works. Pronouns are function morphemes (see the next list) that people process automatically. Each language only has a small set of such words and people can’t easily add to them.

Generally, you can’t simply add to closed-class words at will. For example, people have made various attempts to introduce gender-neutral possessive pronouns into English to help avoid gender bias – proposing invented alternatives, such as ‘Ey’ ‘Hu’ and ‘Peh’, instead of ‘he’ and ‘she’. These attempts largely failed, not necessarily for political reasons, but because of the way language works. Pronouns are function morphemes (see the next list) that people process automatically. Each language only has a small set of such words and people can’t easily add to them.

Just as closed and open-classed words exist, so do the following:

- Function or closed-class morphemes: Tend to be small, frequently occurring words or parts of words, which carry the grammatical structure of a language. These parts of language are typically limited to a few members of each class, and you can’t easily add to them.

- Lexical or open-class morphemes: The meaningful content-laden words of the language; you can easily add new members to these categories. For example, people can create new nouns or verbs such as ‘Google’ or ‘Thatcherism’ (shiver!), but they can’t easily add new members to the closed classes, such as prepositions or determiners.

Reading the long and the short of it

George Zipf demonstrated that in many languages, more frequently used words tend to be shorter than less frequent words (perhaps unsurprisingly as people have to use them so much). If you look at a word-frequency list for English you find some interesting patterns. Some words occur an awful lot – ‘the’ accounts for about 7 per cent of all word occurrences in a typical English text – and the top 100 words in a language account for nearly 50 per cent of all word occurrences.

Really long words are often created, or at least used, for their own sake. Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis (apparently a type of lung disease) is often cited as the longest word in English, but this is arguable on two levels: no one uses it and people can easily create a longer word. In fact, they have: apparently a much-disputed chemical name for the protein ‘titin’ is more than 189,000 letters (and so not much used on Twitter!).

Creativity in language works at multiple levels. For instance, the song-writing Sherman brothers invented the word ‘Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious’. But it follows the same rules as any English word and you can tell it’s English rather than, say, German or Italian.

All words would probably be short if people could get away with it (you see people abbreving[!] all the time). But only enough room exists for a few distinct short words.

All words would probably be short if people could get away with it (you see people abbreving[!] all the time). But only enough room exists for a few distinct short words.

Seeing What Sentences Can Do

Historical change, of the sort we discuss in the preceding section on words, allows psychologists to see how language changes ‘in the wild’ and can help them to understand the more immediate effects that they observe in the lab. One process is grammaticalisation. This is where words for objects and actions (that is, nouns and verbs) become grammatical markers (affixes, prepositions and so on): for example, ‘let us’ meaning ‘allow us’ has changed to ‘let’s’ and lost its meaning.

Some psychologists devote their whole lives to studying the inner lives of sentences – how people produce and understand them.

To investigate sentences, you need to appreciate the key distinction between syntax and semantics:

To investigate sentences, you need to appreciate the key distinction between syntax and semantics:

- Syntax: How words are combined to make phrases and sentences.

- Semantics: What the resulting sentences mean.

Whenever you try to communicate with people you need to understand the sentences that they use and develop your own. This complex process develops from understanding grammar. Sentence structure relates to the structure of cognition and thought (see Chapter 16), and so cognitive psychologists have to understand sentence structure. In this section, we look at how context helps resolve ambiguities in sentences and how grammatical knowledge helps people understand novel sentences.

Looking at sentence ambiguity

All sorts of ambiguities occur at the sentence level, but people rarely notice them because the context makes it clear which interpretation is correct. People rarely notice alternative interpretations unless they’re pointed out – which is exactly what we do in this section!

All sorts of ambiguities occur at the sentence level, but people rarely notice them because the context makes it clear which interpretation is correct. People rarely notice alternative interpretations unless they’re pointed out – which is exactly what we do in this section!

Hammering away at syntactic ambiguity

Parsing a sentence involves grouping words together according to the syntactic rules of the language. But sometimes you can apply the rules to a single sentence in multiple ways and create ambiguous interpretations.

Parsing a sentence involves grouping words together according to the syntactic rules of the language. But sometimes you can apply the rules to a single sentence in multiple ways and create ambiguous interpretations.

Consider the following two short passages:

Consider the following two short passages:

- I was attacked by two men, one of them was carrying a hammer. I hit the man with the hammer.

- I was carrying a hammer when I was attacked by two men. I hit the man with the hammer.

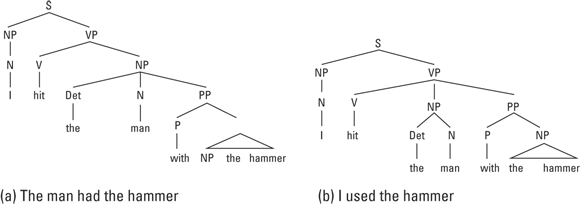

In the first example, the sentence ‘I hit the man with the hammer’ means that I hit the man who was holding the hammer, whereas in the second example it means that I used the hammer to hit the man. This distinction shows that, on its own, the sentence is ambiguous and can have two different interpretations. Figure 14-1 shows the two different ways of packaging the words in the sentence and the two different associated meanings that people can take from the sentence. These two different interpretations are called parses of the sentence.

The two passages show what’s called prepositional phrase attachment ambiguity: as the brain’s sentence processor builds up a phrase structure representation of the sentence, the prepositional phrase ‘with the hammer’ can be attached either to the verb ‘hit’ or to the noun phrase ‘the man’. When you’re reading the passages, your mental grammar allows either option, but they lead to quite different meanings. The word ‘hammer’ means the same in both interpretations, but how it relates to the other parts of the sentence is different – an example of syntactic ambiguity.

The two passages show what’s called prepositional phrase attachment ambiguity: as the brain’s sentence processor builds up a phrase structure representation of the sentence, the prepositional phrase ‘with the hammer’ can be attached either to the verb ‘hit’ or to the noun phrase ‘the man’. When you’re reading the passages, your mental grammar allows either option, but they lead to quite different meanings. The word ‘hammer’ means the same in both interpretations, but how it relates to the other parts of the sentence is different – an example of syntactic ambiguity.

Banking on semantic understanding

In the preceding section, the two sentences in each example have different syntax, but the meaning of the word ‘hammer’ is the same in both cases. In the next example, the two sentences have the same syntax but the semantic interpretation of the word ‘bank’ is different in each case.

- I was walking near the river when I saw a man in the water who appeared to be drowning. I hurried to the bank.

- I was walking down the street when I was attacked and my credit card was stolen. I hurried to the bank.

In these two example cases, the second sentence is ambiguous, despite having the same syntax (you’re hurrying to the bank). But ‘bank’ is ambiguous: it can mean the side of a river or a financial institution. Yet when you encounter the word in a particular context, as here, you tend to have little problem determining the intended meaning.

In these two example cases, the second sentence is ambiguous, despite having the same syntax (you’re hurrying to the bank). But ‘bank’ is ambiguous: it can mean the side of a river or a financial institution. Yet when you encounter the word in a particular context, as here, you tend to have little problem determining the intended meaning.

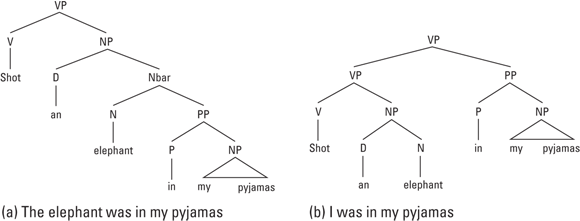

Occasionally, the wrong meaning is conveyed in sentence ambiguity, causing confusion or humour (such as the newspaper headline ‘Man sentenced to life in Scotland’) or Groucho Marx’s line: ‘One morning I shot an elephant in my pyjamas. How he got into my pyjamas I’ll never know.’ The humour arises when listeners use the interpretation in Figure 14-2(a), which means that ‘the elephant was in my pyjamas’.

Writing grammatical rubbish!

Sometimes a sentence can be grammatical (it has correct syntax) and yet meaningless. Even so, people can use their knowledge of syntax creatively to make ‘sense’ of such sentences that they’ve never heard before. They can do so because knowledge of language isn’t simply words, phrases or sentences, but also abstract rules and categories.

Sometimes a sentence can be grammatical (it has correct syntax) and yet meaningless. Even so, people can use their knowledge of syntax creatively to make ‘sense’ of such sentences that they’ve never heard before. They can do so because knowledge of language isn’t simply words, phrases or sentences, but also abstract rules and categories.

A famous example is American linguist Noam Chomsky’s ‘Colourless green ideas sleep furiously’. Chomsky deliberately chose words that would rarely follow one another in normal language – such as ‘colourless green’ or ‘sleep furiously’. He wanted a grammatical and meaningless sentence that people would probably never have heard before to argue his idea that the brain handles grammar (syntax) independently from meaning (semantics).

He also used this sentence to demonstrate the problem with behaviourist accounts of language (refer to Chapter 1). Behaviourists such as BF Skinner believed that people were able to learn language through association – for example, certain words would follow other words in chains of associations. Chomsky designed this sentence so that it has no such associations, and yet people read it with normal English intonation, pausing between the subject phrase (‘Colourless green ideas’) and the verb phrase (‘sleep furiously’).

The behaviourist account struggles to explain how people can use language creatively while still following the rules. Chomsky argued that they can handle these tasks only because they’re equipped with the necessary cognitive machinery to do so.

The behaviourist account struggles to explain how people can use language creatively while still following the rules. Chomsky argued that they can handle these tasks only because they’re equipped with the necessary cognitive machinery to do so.

To demonstrate, read the following two sentences and ask a friend to do the same. As you read them, ask yourself two questions: Had you heard either of the sentences before you read this book? Which one sounds more natural?

To demonstrate, read the following two sentences and ask a friend to do the same. As you read them, ask yourself two questions: Had you heard either of the sentences before you read this book? Which one sounds more natural?

- Colourless green ideas sleep furiously.

- Furiously sleep ideas green colourless.

If, like most people, you read the second ‘sentence’ as a simple list of words in a flat monotone, it’s because it doesn’t fit the rules of grammar.

Talking nonsense

Psychologists have used nonsense poems and sentences to show how the brain processes language, as well as that humans can read such nonsense when it complies with appropriate grammatical rules. Nonsense phrases also help psychologists re-create how children may learn languages.

The author Lewis Carroll played many word games with language, creating nonsense poetry. The most famous example is ‘Jabberwocky’, which appears in Through the Looking Glass. The poem begins:

- ’Twas brillig and the slithy toves

- Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

- All mimsy were the borogroves,

- and the mome raths outgrabe.

Carroll uses English morpho-syntax (written symbols represent syllables corresponding to the meaningful units). The little functional words (‘the’, ‘and’, ‘in’ and so on) are intact, as are the word endings (such as ‘-y’, ‘-s’), but he creates new lexical (words in the mental dictionary) items (such as ‘tove’).

By making up words, Carroll re-creates the experience that children have when they encounter a word for the first time. Just as a child can work out that the plural of the made-up word ‘wug’ is ‘wugs’ (refer to the earlier section ‘Creative morphology: The Wug Test’), readers of this poem can work out that ‘toves’ is the plural of ‘tove’.

By making up words, Carroll re-creates the experience that children have when they encounter a word for the first time. Just as a child can work out that the plural of the made-up word ‘wug’ is ‘wugs’ (refer to the earlier section ‘Creative morphology: The Wug Test’), readers of this poem can work out that ‘toves’ is the plural of ‘tove’.

Pause for thought

Israeli psychologists Asher Koriat and colleagues Seth Greenberg and Hamural Kreiner performed studies that build on the ideas raised by nonsense language. They recorded people reading different types of sentences and analysed the intonation by measuring the length of pauses between words when speaking the sentences.

They used two types of sentence – meaningful and nonsense – and presented each type in a grammatical or a telegraphic form (where all the small function words and morphemes were removed). Here are four examples (including pauses):

- Meaningful with syntax: ‘The fat cat [pause] with the grey stripes [pause] ran [pause] quickly [pause] to the little kitten [pause] that lost [pause] its way [pause] in the noisy street’.

- Meaningful without syntax: ‘Fat cat [pause] grey stripe [pause] run [pause] quick [pause] little kitten [pause] lose [pause] way [pause] noise street’.

- Nonsense with syntax: ‘The sad gate [pause] with the small electricity [pause] went [pause] carefully [pause] to the happy computer [pause] that sang [pause] the leaves [pause] in the front book’.

- Nonsense without syntax: ‘Sad gate [pause] small electricity [pause] go [pause] careful [pause] happy computer [pause] sing [pause] leaf [pause] front book’.

The researchers recorded how long each person paused at each of the indicated points. What they found was intriguing.

People read the syntactic sentences with normal intonation, whether they’re meaningful or nonsense, whereas when the morpho-syntax was missing, their intonation became flat and unnatural. This finding suggests that fluent reading with natural intonation relies more on the syntax of what you’re reading than the semantics: structure is more important than meaning.

People read the syntactic sentences with normal intonation, whether they’re meaningful or nonsense, whereas when the morpho-syntax was missing, their intonation became flat and unnatural. This finding suggests that fluent reading with natural intonation relies more on the syntax of what you’re reading than the semantics: structure is more important than meaning.

Take notice

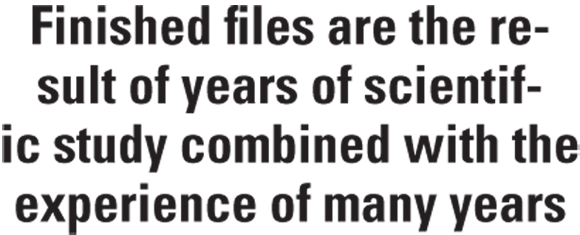

Count the number of times the letter ‘f’ occurs in the passage in Figure 14-3.

Count the number of times the letter ‘f’ occurs in the passage in Figure 14-3.

If you counted 3, you agree with the majority of participants. You’re also wrong. Congratulations if you said 6 – you’re right. Most people miss the ‘f’s in the word ‘of’. Before reading on, can you think why this may be the case?

We suggest two reasons why many people miss the ‘f’ in ‘of’:

- It’s pronounced more like a ‘v’ than an ‘f’: So if you’re relying on the sounds to decode the meaning, you may miss these non-standard pronunciations.

- ‘Of’ is a short, closed-class function word (refer to the earlier section ‘Inventing and accepting new words’ ): Although these functional elements are important for structuring language and for fluent reading, you don’t pay much conscious attention to them.

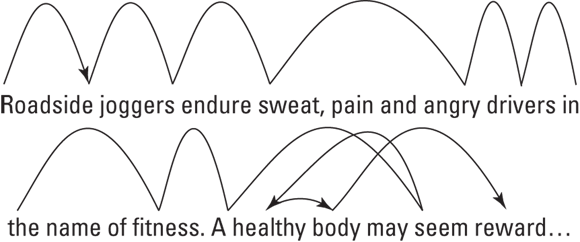

As we describe in Chapter 15, reading involves fixations and leaps. Figure 14-4, for example, shows the eye movements recorded while a person is reading. As you see, the eyes jump over short, frequent and predictable words.

Interestingly, the developmental psychologist Annette Karmiloff-Smith asked young children to count the number of words in various sentences and found that they often omit these function words from their counts.

Building Stories that Mean Something

The infinite creativity we discuss in the preceding section (that allows people to produce and understand new or nonsense sentences) is central to language: people don’t learn language by learning a set of sentences; they learn the rules to produce their own sentences.

The infinite creativity we discuss in the preceding section (that allows people to produce and understand new or nonsense sentences) is central to language: people don’t learn language by learning a set of sentences; they learn the rules to produce their own sentences.

Cognitive psychologists are interested in how people make sense of all this novelty – such as how they come to the right understanding of a narrative they’ve never heard before.

Morton Ann Gernsbacher proposed the Structure Building Framework, a theory of how people build a representation of the meaning of a story as it unfolds. Gernsbacher describes three sub-processes in structure building:

Morton Ann Gernsbacher proposed the Structure Building Framework, a theory of how people build a representation of the meaning of a story as it unfolds. Gernsbacher describes three sub-processes in structure building:

- Laying a foundation: People pay more attention to the start of a story, because it’s used to ‘lay a foundation’ for the structure. The advantage of first mention refers to the fact that information mentioned at the start of a story is easier to access.

- Mapping: This process links new information onto the developing mental representation.

- Shifting: This process affects the accessibility of information. When new information can’t be linked onto the existing chunk of understood text, this process shifts it into a new chunk. For example, when you cross a constituent boundary, such as a new phrase, sentence or paragraph, shifting involves shifting to a new chunk when new information doesn’t fit the existing chunk. Information from the previous chunk becomes less accessible – you can still remember the gist but not the exact form – for example, the exact wording of a sentence.

Two mechanisms aid in these processes:

Two mechanisms aid in these processes:

- Enhancement: Strengthens relevant meanings, so that accessing them is easier when you have an idea of what a story is about.

-

Suppression: Curbs an interpretation or meaning that’s not appropriate in the current context: for example, ‘bug’ as insect versus ‘bug’ as listening device in the following two sentences:

The secret agent did not like the hotel room because it was full of bugs.

The health inspector did not like the hotel room because it was full of bugs.

Cognitive psychologists found (via cross-modal priming – see Chapter 15) that when people hear an ambiguous word (such as ‘bugs’) it simultaneously activates both the appropriate and inappropriate interpretations of the meaning in their mental lexicon (their inner dictionary). But within a very short period of time (less than a second), the inappropriate meaning is ‘shut down’ or inhibited (see Chapter 8).

Cognitive psychologists found (via cross-modal priming – see Chapter 15) that when people hear an ambiguous word (such as ‘bugs’) it simultaneously activates both the appropriate and inappropriate interpretations of the meaning in their mental lexicon (their inner dictionary). But within a very short period of time (less than a second), the inappropriate meaning is ‘shut down’ or inhibited (see Chapter 8).

Chatting about word use

Chatting about word use Playing with sentences

Playing with sentences Telling stories

Telling stories Here are the two smallest parts of language:

Here are the two smallest parts of language: In 2011, US politician Sarah Palin’s emails were made publicly available. Some media reports mentioned her use of the word ‘unflippingbelievable’, where she inserted the mild expletive ‘flipping’ into the word ‘unbelievable’ to create a new word. Interestingly, when people do this kind of thing they always tend to agree on where the word should be inserted. So if you do feel the need to insert ‘flipping’ into ‘fantastic’, you’ll tend to say ‘fan-flipping-tastic’ and not ‘fantas-flipping-tic’.

In 2011, US politician Sarah Palin’s emails were made publicly available. Some media reports mentioned her use of the word ‘unflippingbelievable’, where she inserted the mild expletive ‘flipping’ into the word ‘unbelievable’ to create a new word. Interestingly, when people do this kind of thing they always tend to agree on where the word should be inserted. So if you do feel the need to insert ‘flipping’ into ‘fantastic’, you’ll tend to say ‘fan-flipping-tastic’ and not ‘fantas-flipping-tic’. People alter words using morphology in two basic ways:

People alter words using morphology in two basic ways: Although certain rules guide the morphology of words, not all words follow them. Although you can say ‘jump’, ‘jumping’, ‘jumped’ and ‘open’, ‘opening’, ‘opened’, you run into problems with ‘go’, ‘going’, ‘*goed’ or ‘run’, ‘running’, ‘*runned’: some words (exception words, highlighted with the ‘*’) don’t follow the normal rules.

Although certain rules guide the morphology of words, not all words follow them. Although you can say ‘jump’, ‘jumping’, ‘jumped’ and ‘open’, ‘opening’, ‘opened’, you run into problems with ‘go’, ‘going’, ‘*goed’ or ‘run’, ‘running’, ‘*runned’: some words (exception words, highlighted with the ‘*’) don’t follow the normal rules. Consider the following two short passages:

Consider the following two short passages: