In This Chapter

Defining cognitive psychology

Defining cognitive psychology

Detailing the discipline’s research methods

Detailing the discipline’s research methods

Looking at some limitations

Looking at some limitations

How do you know that what you see is real? Would you notice if someone changed her identity in front of you? How can you be sure that when you remember what you saw, you’re remembering it accurately? Plus, how can you be sure that when you tell someone something that the person understands it in the same way as you do? What’s more fascinating than looking for answers to such questions, which lie at the heart of what it means to be … well … you!

Cognitive psychology is the study of all mental abilities and processes about knowing. Despite the huge area of concern that this description implies, the breadth of the subject’s focus still sometimes surprises people. Here, we introduce you to cognitive psychology, suggesting that it’s fundamentally a science. We show how cognitive psychologists view the subject from an information-processing account and how we use this view to structure this book.

We also describe the plethora of research methods that psychologists employ to study cognitive psychology. The rest of this book uses the philosophies and methods that we describe here, and so this chapter works as an introduction to the book as well.

Introducing Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive psychologists, like psychologists in general, consider themselves to be empirical scientists – which means that they use carefully designed experiments to investigate thinking and knowing. Cognitive psychologists (including us!) are interested in all the seemingly basic things that people take for granted every day: perceiving, attending to, remembering, reasoning, problem solving, decision-making, reading and speaking.

Cognitive psychologists, like psychologists in general, consider themselves to be empirical scientists – which means that they use carefully designed experiments to investigate thinking and knowing. Cognitive psychologists (including us!) are interested in all the seemingly basic things that people take for granted every day: perceiving, attending to, remembering, reasoning, problem solving, decision-making, reading and speaking.

To help define cognitive psychology and demonstrate its ‘scientificness’, we need to define what we mean by a science and then look at the history of cognitive psychology within this context.

Hypothesising about science

Although many philosophers spend hours arguing about the definition of science, one thing that’s central is a systematic understanding of something in order to make a reliable prediction. The scientific method commonly follows this fairly strict pattern:

Although many philosophers spend hours arguing about the definition of science, one thing that’s central is a systematic understanding of something in order to make a reliable prediction. The scientific method commonly follows this fairly strict pattern:

- Devise a testable hypothesis or theory that explains something.

An example may be: how do people store information in their memory? Sometimes this is called a model (you encounter many models in this book).

- Design an experiment or a method of observation to test the hypothesis.

Create a situation to see whether the hypothesis is true: that is, manipulate something and see what it affects.

- Compare the results obtained with what was predicted.

- Correct or extend the theory.

Philosopher Karl Popper suggested that science progresses faster when people devise tests to prove hypotheses wrong: called falsification. After you prove all but one hypothesis wrong about something, you have the answer (the Sherlock Holmes approach – if you exclude the impossible, whatever remains must be true!). This is also called deductive reasoning (see Chapter 18 for the psychology of deduction).

The scientific method has some clear and obvious limitations (or strengths, depending on the way you look at it):

- You can hypothesise and test only observable things. For this reason, many cognitive psychologists don’t see Sigmund Freud, Carl Rogers and others as scientists.

- You must conduct experiments to test a theory. You can’t do research just to find out something new.

Cognitive psychology employs the scientific method vigorously. Everything we describe in this book comes from experiments that have been conducted following this method. Although this does sometimes limit the questions you can ask, it establishes standards that all research must follow.

Cognitive psychology employs the scientific method vigorously. Everything we describe in this book comes from experiments that have been conducted following this method. Although this does sometimes limit the questions you can ask, it establishes standards that all research must follow.

Describing the rise of cognitive psychology

Before cognitive psychology, people used a variety of approaches (or paradigms) to study psychology, including behaviourism, psychophysics and psychodynamics. The year 1956, however, saw the start of a cognitive renaissance, which challenged, in particular, behaviourism. For more background on how cognitive psychology emerged from other scientific disciplines, chiefly behaviourism, check out the nearby sidebar ‘1956: The year cognitive psychology was born’.

We don’t intend to minimise the importance of behaviourism: it ensured that the scientific method was applied to psychology and that experiments were conducted in a controlled way. Cognitive psychology took this strength and carried it into more ingenious scientific studies of cognition.

Looking at the structure of cognition (and of this book)

Fittingly, we’re writing this book to bring cognitive psychology to a wider audience around the 50th anniversary of the first published cognitive psychology textbook (in 1967).

Applications

In Part I, we review the applications of cognitive psychology and why studying it is important. Cognitive psychology has produced some incredibly exciting and interesting findings that have changed how people view psychology and themselves (as you can discover in Chapter 2). But also, people have learnt a great deal about how best to teach, learn and improve themselves from cognitive psychology, something we address in Chapter 3. The applications of cognitive psychology are so wide that studies are used in such disparate fields as computing, social work, education, media technology, human resources and much more besides.

Information-processing framework

In this book, we follow the information-processing model of human cognition. In many ways, this approach to cognition is based on the computer. The idea is that human cognition is based on a series of processing stages. In 1958, Donald Broadbent, a British psychologist, argued that the majority of cognition follows the processing stages we depict in Figure 1-1. The boxes represent stages of cognition and the arrows represent processes within it.

In this book, we follow the information-processing model of human cognition. In many ways, this approach to cognition is based on the computer. The idea is that human cognition is based on a series of processing stages. In 1958, Donald Broadbent, a British psychologist, argued that the majority of cognition follows the processing stages we depict in Figure 1-1. The boxes represent stages of cognition and the arrows represent processes within it.

All cognition fits within this framework. Cognitive psychologists research each box (stage) and each arrow (process) in Figure 1-1 in many different domains. In other words, this framework provides a good structure for how to think about and learn about cognitive psychology (and oddly matches the framework of this book).

Information processing may not be as simple as Figure 1-1, progressing in perfect sequence from the sensory input to long-term storage. Existing knowledge and experience may cause some processing to be in reverse. These two patterns of processing are often referred to as follows:

Information processing may not be as simple as Figure 1-1, progressing in perfect sequence from the sensory input to long-term storage. Existing knowledge and experience may cause some processing to be in reverse. These two patterns of processing are often referred to as follows:

- Bottom-up processing: Physical environment and sensation drive brain processing.

- Top-down processing: Existing knowledge and abilities drive responses.

All forms of cognitive psychology are based on the interaction between bottom-up and top-down processing. No processing is strictly driven by the stimulus or by knowledge.

Cognitive psychologists like the information-processing framework, because people’s interactions with the world are guided by internal mental representations (such as language) that can be revealed by measuring the processing time. Neuroscientists have also found parts of the brain responsible for different cognitive behaviours.

Input

In Part II of this book, we look at the first stage of cognition: input of information. In the computer analogy, this would be a camera recording information or the keyboard receiving key presses.

Cognitive psychologists call the input of information perception: how the brain interprets the information from the senses. Perception is different from sensation, which is exactly what physical information your senses record. Your brain then immediately changes and interprets this information so that it’s easy to process. This process highlights a linear progression from sensation (Chapter 4) to perception (Chapters 5 and 6).

Cognitive psychologists call the input of information perception: how the brain interprets the information from the senses. Perception is different from sensation, which is exactly what physical information your senses record. Your brain then immediately changes and interprets this information so that it’s easy to process. This process highlights a linear progression from sensation (Chapter 4) to perception (Chapters 5 and 6).

Attention follows information input (see Chapter 7). Attention is the first distinct process of the information-processing account, and it’s what links perception with higher-level cognition. Without it, people would simply react to the world in an involuntary manner.

Storage

After you attend to information, it enters your brain’s storage system (see the chapters in Part III). The brain has a number of mechanisms for storing and using information, collectively called memory. We cover short-term memory in Chapter 8 and long-term memory in Chapter 9. You also have stored knowledge and skills (Chapter 10). Although all this knowledge is highly useful, we can’t forget(!) to consider forgetting (Chapter 11), as well as how memory works in everyday life and some of the applications of memory research (Chapter 12).

In the computer analogy of cognition, short-term memory is the RAM: it has limited capacity and simply keeps the information you’re currently using available to you. Just as you can’t have too many applications or windows open on a computer simultaneously without slowing it down, the same applies to human short-term memory. Long-term memory and knowledge is the hard-disk space – a vast store of information.

In the computer analogy of cognition, short-term memory is the RAM: it has limited capacity and simply keeps the information you’re currently using available to you. Just as you can’t have too many applications or windows open on a computer simultaneously without slowing it down, the same applies to human short-term memory. Long-term memory and knowledge is the hard-disk space – a vast store of information.

Language and thought

Sensation and perception are quite low-level cognitive functions: they’re fairly simple processes that many animals can do. Memory is a slightly higher-level cognitive function, but the highest-level functions are the ones that animals can’t do, according to some psychologists – language and thought (see Parts IV and V):

Researching Cognitive Psychology

People have devised a number of methods for researching cognitive psychology. Plus, technological advances allow psychologists to explore how the brain functions. In this section, we describe how experiments, computational models, work with patients and brain scanning helped psychologists to understand how the cognitive system works.

Testing in the laboratory

The tightly controlled laboratory experiment is one of the most commonly used techniques for researching cognitive psychology. Psychologists take normal people (like those exist!) – usually university students (narrowing the definition of normal to those generally well-educated and intelligent) – place these participants in small cubicles and show them things on a computer. Each person is tested in exactly the same way and the experimenters have complete control over what the person sees (as long as the computers follow the given instructions!).

Participants are usually unaware of exactly what they’re going to do. They’re given instructions to follow a set of tasks on the computer, often in the form of a game. (Indeed, a few years ago Nintendo released a brain game that included several cognitive psychological tasks, such as the Stroop effect task we describe in Chapter 7.) Participants make responses on the keyboard, mouse or other specially designed equipment.

Participants are usually unaware of exactly what they’re going to do. They’re given instructions to follow a set of tasks on the computer, often in the form of a game. (Indeed, a few years ago Nintendo released a brain game that included several cognitive psychological tasks, such as the Stroop effect task we describe in Chapter 7.) Participants make responses on the keyboard, mouse or other specially designed equipment.

The experimenters take the participants’ responses, usually in terms of measures of response speed and their accuracy, and use statistics to work out whether the hypothesis and cognitive psychological model is correct or not. These statistics allow researchers to see whether the sample tested reflects the whole population of people that could’ve been tested. Then the psychologists tell the world!

Crucially, experimenters must test lots of people to get reliable results. If you only test a few people, you may get very odd results, because the world contains lots of odd individuals and they usually turn up for experiments! After testing enough people, you can see the average of lots of people, which tells you whether to trust your hypothesis or not.

Crucially, experimenters must test lots of people to get reliable results. If you only test a few people, you may get very odd results, because the world contains lots of odd individuals and they usually turn up for experiments! After testing enough people, you can see the average of lots of people, which tells you whether to trust your hypothesis or not.

Modelling with computers

One approach to testing cognitive psychology doesn’t use people at all! Researchers can employ computers to mimic human cognition in what’s called computational modelling. A good computational model is specific enough to predict human behaviour. These kinds of theories are more precise than the often vague verbal theories that earlier cognitive psychologists used.

One approach to testing cognitive psychology doesn’t use people at all! Researchers can employ computers to mimic human cognition in what’s called computational modelling. A good computational model is specific enough to predict human behaviour. These kinds of theories are more precise than the often vague verbal theories that earlier cognitive psychologists used.

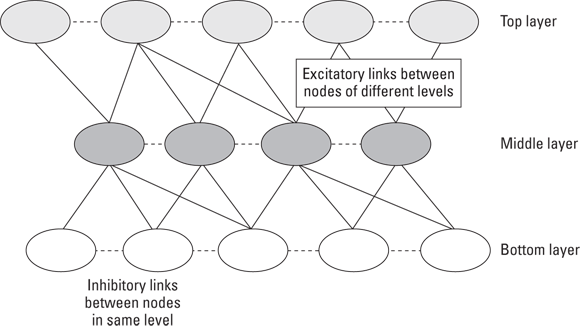

Computational models are based around different types of structure (or architecture). Connectionist models are by far the most common of cognitive models. They work by having layers of nodes connected to each other by links that either promote or stop activity. Nodes in the same layer are usually inhibitory to each other (they prevent other nodes in the same layer from activating). We draw out a simple connectionist model in Figure 1-2, representing concepts and knowledge as a pattern of activation within the model. We go into much more detail in Chapter 10.

Computational models are based around different types of structure (or architecture). Connectionist models are by far the most common of cognitive models. They work by having layers of nodes connected to each other by links that either promote or stop activity. Nodes in the same layer are usually inhibitory to each other (they prevent other nodes in the same layer from activating). We draw out a simple connectionist model in Figure 1-2, representing concepts and knowledge as a pattern of activation within the model. We go into much more detail in Chapter 10.

Production models are based around formal logic (Chapter 18). They rely on a series of ‘if … then’ statements. The idea is that stored knowledge exists in terms of ‘if this happens, then this will’. Another technique – artificial intelligence – involves constructing a computer to produce intelligent outcomes, though it doesn’t have to reflect human processing.

Computational modelling can be hugely successful at explaining human behaviour, but the models created often run the risk of being incredibly complex and difficult to understand. Also, they can be modified too easily to account for a very limited set of data, making them not very useful.

Computational modelling can be hugely successful at explaining human behaviour, but the models created often run the risk of being incredibly complex and difficult to understand. Also, they can be modified too easily to account for a very limited set of data, making them not very useful.

Working with brain-damaged people

Cognitive neuropsychology is the study of brain-damaged patients in an attempt to understand normal cognition. Often the ingenious studies that cognitive psychologists devise are run on people with various types of brain damage to see whether they perform differently. The aim is to identify what processes take place where in the brain, and what groups of tasks are related in terms of cognitive functioning.

Cognitive neuropsychology is the study of brain-damaged patients in an attempt to understand normal cognition. Often the ingenious studies that cognitive psychologists devise are run on people with various types of brain damage to see whether they perform differently. The aim is to identify what processes take place where in the brain, and what groups of tasks are related in terms of cognitive functioning.

The neuropsychological approach has been around since the end of the nineteenth century. It has several key assumptions, as Max Coltheart, a noted Australian neuropsychologist, indicated:

The neuropsychological approach has been around since the end of the nineteenth century. It has several key assumptions, as Max Coltheart, a noted Australian neuropsychologist, indicated:

- Modularity: The cognitive system contains separate parts that operate largely on their own.

- Domain specificity: Modules only work for one type of stimulus.

- Anatomical modularity: Each cognitive module is located in a specific part of the brain.

- Uniformity of functional architecture across people: Every brain in the world is the same.

- Subtractivity: Damage to the brain only removes abilities, but doesn’t add to or change the brain in any other way. This assumption is largely wrong, especially in children, whereas the other points are at least defendable.

Neuropsychologists are always looking for dissociations or even double dissociations as the best form of evidence:

Neuropsychologists are always looking for dissociations or even double dissociations as the best form of evidence:

- Dissociation: Where they find a group of patients who perform poorly on one task but normally on others.

- Double dissociation: Where they have two groups of patients who show complementary patterns of impairment (so that one group is impaired on task A but not B, and the other group is impaired on B but not A). This approach shows that the two tasks are functionally different (and based on different brain structures).

Often, neuropsychologists use case studies. They look at individuals with a certain type of brain damage to understand what different parts of the brain do to a wide range of tasks. Certain people have been extensively researched and so have contributed to the knowledge of the brain more than many researchers! Chapter 21 has ten case studies for you to read.

Analysing the brain

Cognitive neuroscience is where researchers use expensive equipment to measure the brain when it’s doing something. The brain consists of 100 billion neurons and each neuron is connected to up to 10,000 other neurons (that’s a complex lump of goo inside your head). Yet researchers using neuroimaging have done a wonderful job of shedding light on it.

Cognitive neuroscience is where researchers use expensive equipment to measure the brain when it’s doing something. The brain consists of 100 billion neurons and each neuron is connected to up to 10,000 other neurons (that’s a complex lump of goo inside your head). Yet researchers using neuroimaging have done a wonderful job of shedding light on it.

The German neurologist, Korbinian Brodmann, was the first to map the brain directly. He named 52 different brain areas and his descriptions are still used today. The assumption is that each area does a slightly different thing (based on the modularity assumption of the cognitive neuropsychologists we describe in the preceding section).

Neuroscientists use a number of ways to study cognitive psychology:

Neuroscientists use a number of ways to study cognitive psychology:

- Single cell recording: An electrode records the activity of single cells, which usually requires drilling into the skull and brain (so not something to undergo while eating lunch).

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Electrodes placed on the surface of the scalp measure the electrical activity of the brain. Electrical spikes occur due to the presentation of certain stimuli, called event-related potentials (ERPs). This technique records brain activity quickly but isn’t good at finding the source of the activity.

- Positron emission tomography (PET): Radioactive substances are absorbed into the blood and a scanner picks them up when the blood enters the brain.

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): A large (and noisy) scanner detects the level of oxygen in the blood as it enters the brain. The more blood in certain areas, the more it’s assumed to be active. This technique isn’t good at measuring the speed of brain processing, but it can localise the source quite accurately.

- Magneto-encephalography (MEG): Similar to EEG, this method measures magnetic fields produced by the brain’s electrical activity.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS): A large magnetic pulse is sent into part of the brain, which stops that part working for a brief period.

- Transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS): This method involves sending a small electrical current through parts of the brain to see how enhanced or reduced activity to a particular region affects performance on certain cognitive tasks.

These techniques can be useful in establishing which part of the brain is responsible for processing certain things, although none of them are completely accurate. To use neuroimaging techniques appropriately, you need to run a good, well-controlled cognitive test that really measures only one ability (to pinpoint which part of the brain is responsible for that ability – see the next section).

These methods also suffer from the fact that completing research while having your brain measured is an odd experience. In the case of fMRI, it involves lying down inside a big magnet – hardly the typical position when completing any form of cognition. Therefore, these techniques may change participants’ behaviour.

These methods also suffer from the fact that completing research while having your brain measured is an odd experience. In the case of fMRI, it involves lying down inside a big magnet – hardly the typical position when completing any form of cognition. Therefore, these techniques may change participants’ behaviour.

Defining cognitive psychology

Defining cognitive psychology Detailing the discipline’s research methods

Detailing the discipline’s research methods Looking at some limitations

Looking at some limitations Cognitive psychologists, like psychologists in general, consider themselves to be empirical scientists – which means that they use carefully designed experiments to investigate thinking and knowing. Cognitive psychologists (including us!) are interested in all the seemingly basic things that people take for granted every day: perceiving, attending to, remembering, reasoning, problem solving, decision-making, reading and speaking.

Cognitive psychologists, like psychologists in general, consider themselves to be empirical scientists – which means that they use carefully designed experiments to investigate thinking and knowing. Cognitive psychologists (including us!) are interested in all the seemingly basic things that people take for granted every day: perceiving, attending to, remembering, reasoning, problem solving, decision-making, reading and speaking. Cognitive psychology employs the scientific method vigorously. Everything we describe in this book comes from experiments that have been conducted following this method. Although this does sometimes limit the questions you can ask, it establishes standards that all research must follow.

Cognitive psychology employs the scientific method vigorously. Everything we describe in this book comes from experiments that have been conducted following this method. Although this does sometimes limit the questions you can ask, it establishes standards that all research must follow.

Cognitive psychologists call the input of information perception: how the brain interprets the information from the senses. Perception is different from sensation, which is exactly what physical information your senses record. Your brain then immediately changes and interprets this information so that it’s easy to process. This process highlights a linear progression from sensation (

Cognitive psychologists call the input of information perception: how the brain interprets the information from the senses. Perception is different from sensation, which is exactly what physical information your senses record. Your brain then immediately changes and interprets this information so that it’s easy to process. This process highlights a linear progression from sensation ( Participants are usually unaware of exactly what they’re going to do. They’re given instructions to follow a set of tasks on the computer, often in the form of a game. (Indeed, a few years ago Nintendo released a brain game that included several cognitive psychological tasks, such as the Stroop effect task we describe in

Participants are usually unaware of exactly what they’re going to do. They’re given instructions to follow a set of tasks on the computer, often in the form of a game. (Indeed, a few years ago Nintendo released a brain game that included several cognitive psychological tasks, such as the Stroop effect task we describe in