Chapter 17

Uncovering How People Solve Problems

In This Chapter

Revealing mental processes with the Gestalt school

Revealing mental processes with the Gestalt school

Solving problems with computers and experts

Solving problems with computers and experts

Considering cognitive research in learning

Considering cognitive research in learning

The film Apollo 13 depicts the true story of how disaster struck this lunar mission. An explosion forced the crew to retire to the spacecraft’s small command module and use it as a ‘life boat’ to return to Earth. But the module needed a better air filter for them to survive the journey and they didn’t have one that fit its life support system.

A famous scene in the film dramatically depicts the NASA engineers on Earth re-creating the available materials on the stricken spacecraft and frantically trying to use them to construct an air filter. They succeed and instruct the astronauts how to make a filter out of (among other things) a pair of socks, some duct tape and hoses from the space suits they no longer needed.

This event is a particularly compelling example of problem-solving, but innovative thinking isn’t limited to NASA engineers (it’s not rocket science …): you see or use this skill on a regular basis. People solve problems all the time, although they may take the ability for granted and not notice when they’re doing it. When someone asks you how you solve problems, you can struggle to put the processes into words. Try it now: think about the mental processes you go through when solving a problem.

For example, our current problem is to write this paragraph and yours is to understand the psychology of problem-solving. The fact that you’re reading this text suggests that you’re actively engaged in solving that problem. The means at our disposal are words, which we’re free to arrange in any order – though only certain orders will do the job. The problem is ill-defined, because no single correct paragraph or simple process exists to solve the problem. For this reason, psychologists often focus on well-defined problems – ones with definite goals and clearly specified rules.

The ability to solve problems is important for coping with the demands of everyday life. This chapter covers the main perspectives on how people develop ways of solving simple and complex problems. We look at the methods psychologists use to study problem-solving and some of the theories that have emerged to explain how people go about it.

Experimenting to Reveal Thought Processes: Gestalt Psychology

Before cognitive psychology emerged in the mid-20th century, two prominent schools of thought existed on how people solve problems:

Before cognitive psychology emerged in the mid-20th century, two prominent schools of thought existed on how people solve problems:

- Behaviourists: Liked to limit their studies to observable behaviour; their explanations of problem-solving focused on the concepts of trial and error and reinforcement.

- Gestaltists: Disagreed with the behaviourists on the issue of studying mental processes and mental representations. They sought to explain the psychological activities behind problem-solving. In this sense, they’re like the forerunners of cognitive psychologists, and so they’re the focus of this section.

Defining the problem

Karl Duncker, a German Gestalt psychologist, stated that ‘a problem arises when a living creature has a goal, but does not know how this goal is to be reached. Whenever one cannot go from a given situation to the desired situation simply by action, then there has to be recourse to thinking’.

When talking about a problem, the desired situation is called the goal state and your starting position is the initial state. You have at your disposal a range of actions (or operators) that you can apply. A problem can require you to overcome some specific obstacles or come up with an efficient solution, such as achieving the goal with the fewest actions.

When talking about a problem, the desired situation is called the goal state and your starting position is the initial state. You have at your disposal a range of actions (or operators) that you can apply. A problem can require you to overcome some specific obstacles or come up with an efficient solution, such as achieving the goal with the fewest actions.

Well-defined problems are ones in which the goal state, the initial state and the operators you can apply are all well-defined. Many puzzles, such as the Rubik’s cube, fall into this category, but lots of real-world problems vary in the extent to which they’re well-defined.

Monkeying around with insight

Wolfgang Köhler, another German Gestalt psychologist, believed that animals and people are capable of more complex learning, involving insight and thought, than the trial and error approach that behaviourists put forward. He studied problem-solving by chimpanzees at a primate research station on the island of Tenerife, and published this research in a famous book entitled The Mentality of Apes in 1917.

Köhler argued that Thorndike’s puzzle boxes (see the nearby sidebar ‘Trial and error versus thought’) were unnatural and went so far outside an animal’s experience that the cats couldn’t apply their normal thought processes. He wanted to test animals with puzzles more suited to their natural intellect to see them demonstrate their mental abilities.

Köhler devised various puzzles in which chimps had to use objects to retrieve out-of-reach bananas. In one example, a chimp who’d already learned to use a stick to reach a banana was given two sticks, neither of which was long enough. At first the chimp tried both sticks and gave up when neither worked. But after some time sulking, the chimp stuck one stick into the end of the other to make a stick long enough to retrieve the cherished banana. A delicious result!

Behaviourists would object to us using words such as ‘sulking’ and ‘cherished’. They’d see them as too mentalistic, because they refer to concepts that can’t be observed and shouldn’t be assumed; yet they’d have trouble explaining this apparent moment of ‘insight’ by the chimpanzee. No trial and error learning existed before the chimp combined the two sticks, and it’s unlikely that the animal had previous experience of this type of problem. Therefore, it seems to have arrived at the solution purely by thinking.

The behaviourist and Gestalt schools’ disagreement reached beyond non-human animals. The former didn’t just object to anthropomorphising (attributing human-like qualities to animals); they also objected to explanations of human thinking that referred to mental states or processes. Sidney Morgenbesser, an American philosopher famous for his witticisms, asked BF Skinner: ‘Let me see if I understand your thesis: you think we shouldn’t anthropomorphise people?’

The behaviourist and Gestalt schools’ disagreement reached beyond non-human animals. The former didn’t just object to anthropomorphising (attributing human-like qualities to animals); they also objected to explanations of human thinking that referred to mental states or processes. Sidney Morgenbesser, an American philosopher famous for his witticisms, asked BF Skinner: ‘Let me see if I understand your thesis: you think we shouldn’t anthropomorphise people?’

Getting stuck in a rut: Functional fixedness

Karl Duncker identified a particular limitation that often restricts people from spotting novel uses for familiar objects. He called this functional fixedness, because humans’ idea of how an object can function is fixed by their past experience. For example, perhaps you’ve been at a party or picnic when everyone has brought beer bottles but no one has a bottle opener. Resourceful individuals look for something else to open the bottles while others panic or sulk, their ability to see alternative uses for objects limited by functional fixedness.

To illustrate his idea, Duncker provides this problem. You’re given a box of drawing pins (thumb tacks), a candle and a book of matches. Your task is to fix the candle to the wall. Try to solve it before reading on.

To illustrate his idea, Duncker provides this problem. You’re given a box of drawing pins (thumb tacks), a candle and a book of matches. Your task is to fix the candle to the wall. Try to solve it before reading on.

The solution is to empty the drawing pins out of the box, use them to attach the box to the wall and use the box as a candle holder. People often have difficulty solving this problem, because they can’t see beyond the box’s use for holding the pins to its more general possibilities.

We may have primed you to get the right solution by talking about seeing alternative functions for objects, but Duncker’s participants didn’t have this prompt. In general, a good tip for solving these kinds of problems is to question your natural tendency to make assumptions about how things can be used or how your actions are limited.

We may have primed you to get the right solution by talking about seeing alternative functions for objects, but Duncker’s participants didn’t have this prompt. In general, a good tip for solving these kinds of problems is to question your natural tendency to make assumptions about how things can be used or how your actions are limited.

Watching the Rise of the Computers: Information Processing Approaches

Although the Gestalt psychologists’ experiments (refer to the preceding section) showed that cognitive processes and representations, such as insight and functional fixedness, occur in problem-solving, they didn’t address the question of how. That issue was left until the cognitive revolution (see Chapter 1) prompted a return to the study of problem-solving and the attempt to pin down precisely what processes happen in the brain when a person, or an animal, solves a problem.

Although the Gestalt psychologists’ experiments (refer to the preceding section) showed that cognitive processes and representations, such as insight and functional fixedness, occur in problem-solving, they didn’t address the question of how. That issue was left until the cognitive revolution (see Chapter 1) prompted a return to the study of problem-solving and the attempt to pin down precisely what processes happen in the brain when a person, or an animal, solves a problem.

Yet how to study thought is a problem for cognitive psychology; despite what popular culture may have you believe, you can’t observe thoughts.

What psychologists can do is use technology, such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), to observe the physical activity in the brain that’s associated with thoughts. They can detect differences between distinctly different kinds of thought so that, for example, by asking a person to think of one situation or another, they can see relatively distinct patterns of activity. (Such techniques have been used to test patients in a persistent vegetative state.) Psychologists can also see the effect that damage to different areas of the brain has on a person’s problem-solving ability. For example, patients with damage to the frontal lobes of the brain often show problems with planning and problem-solving.

What psychologists can do is use technology, such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), to observe the physical activity in the brain that’s associated with thoughts. They can detect differences between distinctly different kinds of thought so that, for example, by asking a person to think of one situation or another, they can see relatively distinct patterns of activity. (Such techniques have been used to test patients in a persistent vegetative state.) Psychologists can also see the effect that damage to different areas of the brain has on a person’s problem-solving ability. For example, patients with damage to the frontal lobes of the brain often show problems with planning and problem-solving.

Welcoming computers to the struggle

Computers provided a new way of thinking about thinking and were soon being applied to the study of psychology. In this new information processing approach, problem-solving was broken down into its basic constituent processes, which psychologists then simulated on a computer.

Computers provided a new way of thinking about thinking and were soon being applied to the study of psychology. In this new information processing approach, problem-solving was broken down into its basic constituent processes, which psychologists then simulated on a computer.

Nobel-prize winners Alan Newell and Herb Simon set about developing computer programs to simulate the processes a person goes through when solving a problem. On the one hand, they were developing ways to program computers to solve problems and thus contributing to computer science. On the other hand, they were trying to replicate the processes that occur when a person solves a problem; in trying to understand this, they contributed to the study of psychology as well. In other words, they were using computers to demonstrate how humans may solve problems.

Newell and Simon worked on a general approach to solving well-defined problems (with clear goals and specified rules), such as the following one. Try it out but also think about what makes it so tricky to solve.

A farmer has to cross a river with a wolf, a goat and a cabbage. (Don’t consider why or we’ll never get to the problem. Just say that he’s a bit batty and leave it at that!) He has a rowing boat that can carry himself and one of his three items of cargo at a time. He has to get all three items across the river, but he can’t leave the wolf alone with the goat or wolfie will eat it, and he can’t leave the goat alone with the cabbage for the same reason. How does the farmer get the three items across the river?

A farmer has to cross a river with a wolf, a goat and a cabbage. (Don’t consider why or we’ll never get to the problem. Just say that he’s a bit batty and leave it at that!) He has a rowing boat that can carry himself and one of his three items of cargo at a time. He has to get all three items across the river, but he can’t leave the wolf alone with the goat or wolfie will eat it, and he can’t leave the goat alone with the cabbage for the same reason. How does the farmer get the three items across the river?

Here’s the solution:

- Take the goat from side 1 to side 2.

- Return to side 1.

- Take the cabbage to side 2.

- Return to side 1, taking the goat with you.

- Take the wolf to side 2.

- Return to side 1.

- Take the goat to side 2.

How did you get on? The difficulty in this problem lies in the need to make moves that appear to be moving away from the solution. When the farmer takes the goat back from side 2 to side 1, you appear to be undoing your actions. But you aren’t returning to the initial state, because the cabbage is no longer on side 1. Therefore, you can now leave the goat on side 1 while bringing the wolf across.

How did you get on? The difficulty in this problem lies in the need to make moves that appear to be moving away from the solution. When the farmer takes the goat back from side 2 to side 1, you appear to be undoing your actions. But you aren’t returning to the initial state, because the cabbage is no longer on side 1. Therefore, you can now leave the goat on side 1 while bringing the wolf across.

Seeing the state space approach

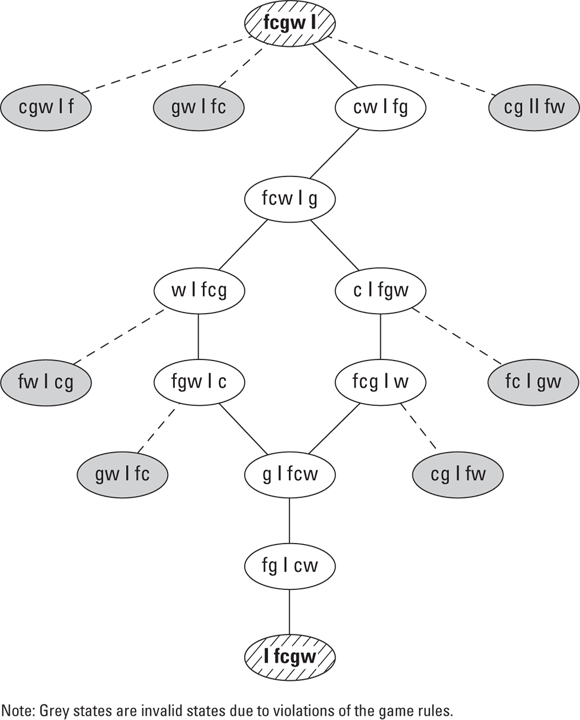

To tackle well-defined problems, Newell and Simon proposed a problem space. Starting with the goal state, you consider what would happen if you were to carry out each of the possible moves. The result is a state space diagram showing all the possible moves, which allows you to find the shortest path from the start state to the goal state (see Figure 17-1).

To tackle well-defined problems, Newell and Simon proposed a problem space. Starting with the goal state, you consider what would happen if you were to carry out each of the possible moves. The result is a state space diagram showing all the possible moves, which allows you to find the shortest path from the start state to the goal state (see Figure 17-1).

Perusing protocol analysis

Newell and Simon also used a technique called protocol analysis, in which they asked participants to talk through their thinking process as they solved well-defined problems. Protocol analysis established that people often use means-ends analysis: they start with the goal they want to achieve (the ends) and work backwards, identifying which methods (the means) at their disposal they can use to achieve the ends.

Newell and Simon also used a technique called protocol analysis, in which they asked participants to talk through their thinking process as they solved well-defined problems. Protocol analysis established that people often use means-ends analysis: they start with the goal they want to achieve (the ends) and work backwards, identifying which methods (the means) at their disposal they can use to achieve the ends.

Examining Expert Problem-Solving

As well as studying how people solve individual problems, cognitive psychologists are also interested in how people develop expertise in solving problems of a particular type.

Analysing the memories of expert chess players

Human short-term memory has a limited capacity for storing units of information, which George Miller called chunks (see Chapter 8). Miller estimated that people can remember about seven chunks of information, although more recent studies suggest that people’s capacity is even lower than that.

Human short-term memory has a limited capacity for storing units of information, which George Miller called chunks (see Chapter 8). Miller estimated that people can remember about seven chunks of information, although more recent studies suggest that people’s capacity is even lower than that.

Research with expert chess players has revealed this ability. One clue to what changes in the brain and in processing as a person becomes an expert at chess is provided by a study on their memory for chess board positions. Expert chess players are better at remembering different arrangements of chess pieces on a board than novices. But this advantage only works for genuine arrangements of pieces from real chess games. When tested using random arrangements of pieces, the experts fare little better than novices.

Expert chess players can remember more positions not because their memory capacity has increased but because they’ve amassed a much greater ‘library’ of chess positions, which they can recognise and store as a single chunk. Whereas a novice may have to remember each of three pieces as three separate chunks, an expert can recognise the configuration of pieces as a single chunk. As when learning a language, the novices are treating each piece like a separate letter, whereas the experts know larger ‘words’ involving common arrangements of pieces.

Expert chess players can remember more positions not because their memory capacity has increased but because they’ve amassed a much greater ‘library’ of chess positions, which they can recognise and store as a single chunk. Whereas a novice may have to remember each of three pieces as three separate chunks, an expert can recognise the configuration of pieces as a single chunk. As when learning a language, the novices are treating each piece like a separate letter, whereas the experts know larger ‘words’ involving common arrangements of pieces.

Learning to become an expert

Newell and Simon’s ground-breaking work on human problem-solving (refer to the earlier ‘Welcoming computers to the struggle’ section) established certain general principles, such as means-ends analysis, by which experts solve problems. John Anderson developed the ACT* theory, which incorporates not only a mechanism for general problem-solving but also addresses the question of skill acquisition – how do people build the knowledge that enables them to become better at a skill?

At its heart, Anderson’s model has a production rule, which is a basic unit of a procedural skill composed of two parts: a condition that gives the context in which the rule applies and an action that specifies what to do in that situation. For example, if someone knocks on your door (the condition) then the action is that you get up and open the door (unless your favourite programme is on the TV!).

At its heart, Anderson’s model has a production rule, which is a basic unit of a procedural skill composed of two parts: a condition that gives the context in which the rule applies and an action that specifies what to do in that situation. For example, if someone knocks on your door (the condition) then the action is that you get up and open the door (unless your favourite programme is on the TV!).

Anderson’s model allowed him to construct computer models of how students develop skills in areas such as mathematics and computer programming. This model simulated the learning of a skill as the gradual development and strengthening of specific production rules and was able to identify errors due to the misapplication of specific rules. So, in the preceding example, you hear a knock on the door and the action is to open it. But learning applies such that you may need to specify the condition (for example, at night opening the door may not be safe, and so you don’t, or during the day the caller may be a door-to-door salesperson and so you pretend not to hear it). With experience, the production rule becomes refined.

Emulating the experts to improve your problem-solving

Even if you don’t want to become a chess grand master, you can still become an expert problem-solver by following these helpful hints:

- Practice: Learning develops slowly, piece by piece. To be an expert you need to amass a vast number of chunks of relevant experience. Some research shows that around 10,000 hours’ practice is typical (though this is a bit of a myth with caveats regarding how often the skill is practised and the type of skill), though you can become proficient with less practice at lots of smaller skills.

-

Vary your experiences: If you deal with too many problems of the same kind you can become mired in repeated patterns of thinking (see ‘Getting stuck in a rut: Functional fixedness’ earlier in this chapter). Instead, try to build up a rich memory of different patterns (read the research in the later section ‘Improving problem-solving comes with experience’).

Vary your experiences: If you deal with too many problems of the same kind you can become mired in repeated patterns of thinking (see ‘Getting stuck in a rut: Functional fixedness’ earlier in this chapter). Instead, try to build up a rich memory of different patterns (read the research in the later section ‘Improving problem-solving comes with experience’).

- Group problems sensibly: Doing so allows you to tackle ones with similar underlying structures together and promotes the development of helpful analogies and more abstract patterns (see the later ‘Using analogies in problem-solving’ section for more).

- Keep an open mind: Don’t assume that limitations apply, but instead consider how a new problem may resemble a familiar one. Analogies may exist with situations that seem different on the surface.

-

Relax: After you’ve done the hard work, take some time off. Many people report that novel and useful solutions to problems come to them after they stop working, relax, go for a walk or even to sleep. An unconscious process seems to sift through your memory looking for something that matches the structure of your current problem.

Relax: After you’ve done the hard work, take some time off. Many people report that novel and useful solutions to problems come to them after they stop working, relax, go for a walk or even to sleep. An unconscious process seems to sift through your memory looking for something that matches the structure of your current problem.

One example is the dreams of Friedrich August Kekulé, a German chemist. After struggling to discover the chemical makeup of a particular molecule, he slept. In a dream, he saw atoms dance around and then form themselves into strings, moving in a snake-like fashion. The snake of atoms formed a circle and it looked like a snake eating its own tail. Allowing his mind to relax and wander, Kekulé was able to discover the cyclic structure of benzene.

Modelling How Learners Learn with Intelligent Tutoring Systems

Intelligent tutoring systems aim to model students’ and learners’ thought processes as they develop a skill and attempt to identify gaps or misunderstandings in their knowledge. For example, computer models such as ACT-R have been applied to everyday areas.

Intelligent tutoring systems aim to model students’ and learners’ thought processes as they develop a skill and attempt to identify gaps or misunderstandings in their knowledge. For example, computer models such as ACT-R have been applied to everyday areas.

British psychologists Richard Burton and John Seeley Brown studied how children solved basic mathematical problems such as addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Getting computers to calculate sums correctly is easy, but Brown and Burton wanted to reproduce the faulty thought processes that lead to wrong answers. For example, a child may forget to carry the tens when adding two numbers.

Brown and Burton took children’s answers to a series of simple calculations and used a computer model to simulate the pattern of correct and incorrect answers that they produced. The psychologists simulated the children’s thought processes using a set of production rules, each of which addressed different stages in a calculation (such as carrying tens). They then systematically replaced these rules with ‘buggy’ versions, which simulated a particular misunderstanding that a child may have. By trying out different combinations of correct and buggy rules they found the combination that re-created the child’s answers. This enabled the model to diagnose what particular mistakes each child was making.

Brown and Burton’s work was pioneering in the 1980s, but such cognitive modelling of the learner is at the heart of much recent research in online education. The ability to test automatically students’ understanding and diagnose the reasons for their mistakes can greatly enhance online assessment. It can enable a computer program to be more responsive to students’ needs by identifying their misunderstandings.

Brown and Burton’s work was pioneering in the 1980s, but such cognitive modelling of the learner is at the heart of much recent research in online education. The ability to test automatically students’ understanding and diagnose the reasons for their mistakes can greatly enhance online assessment. It can enable a computer program to be more responsive to students’ needs by identifying their misunderstandings.

Improving problem-solving comes with experience

Psychologists can produce a model of a human learner that identifies the areas where the person lacks knowledge or has particular misconceptions. Harriet Shaklee and Michael Mims studied the way in which people form associations between events. In this fascinating area of study, you encounter all sorts of interesting questions about everyday experience. For example, people often form illusory correlations between events (see Chapter 10), which are when the human brain links two rarely occurring events together.

Shaklee and Mims hypothesised that people use increasingly better strategies as they develop. They created a set of problems that were carefully designed so that they could distinguish between several different cognitive strategies for forming associations. They then gave these problems to different age-groups and recorded the errors made by each group. They found evidence of increasing use of more advanced cognitive strategies with age. All groups could tackle the simplest versions, but only older, better educated individuals correctly answered the most difficult problems.

Shaklee and Mims hypothesised that people use increasingly better strategies as they develop. They created a set of problems that were carefully designed so that they could distinguish between several different cognitive strategies for forming associations. They then gave these problems to different age-groups and recorded the errors made by each group. They found evidence of increasing use of more advanced cognitive strategies with age. All groups could tackle the simplest versions, but only older, better educated individuals correctly answered the most difficult problems.

Using analogies in problem-solving

If you’ve already experienced and solved a problem, you’re more likely to be able to solve a dilemma with the same underlying structure, even if it appears different on the surface. By applying Newell and Simon’s state space analysis (refer to the earlier section ‘Seeing the state space approach’), you can identify that underlying structure. Psychologists call two problems with an identical underlying structure isomorphic.

For example, the problem of getting a goat, cabbage and wolf across a river has the same structure as a number of other popular puzzles, including the fox, goose and bag of beans one (where you can’t leave the fox and goose or the goose and bag of beans alone together). If you draw the state space graph for the two different versions of the puzzle, you find that they have identical structures and the optimal path from the start state to the goal state is the same.

Therefore, when you know how to solve the wolf, goat and cabbage problem you can apply the same skill to the fox, goose and bag of beans one. You just need to recognise how the new problem maps onto the one you’ve experienced. This is a form of what’s called analogical problem solving, which is solving a new problem by recognising how it resembles a problem you’ve experienced before. You thus have a solution, or at least a method, for solving the problem without having to go through the much longer learning process of tackling such a problem for the first time.

Therefore, when you know how to solve the wolf, goat and cabbage problem you can apply the same skill to the fox, goose and bag of beans one. You just need to recognise how the new problem maps onto the one you’ve experienced. This is a form of what’s called analogical problem solving, which is solving a new problem by recognising how it resembles a problem you’ve experienced before. You thus have a solution, or at least a method, for solving the problem without having to go through the much longer learning process of tackling such a problem for the first time.

In the real world, however, problems have so many variations that a new problem rarely matches one that you’ve previously experienced in every detail, and so you have to look for similarities rather than exact fits.

In the real world, however, problems have so many variations that a new problem rarely matches one that you’ve previously experienced in every detail, and so you have to look for similarities rather than exact fits.

Psychologists Mary Gick and Keith Holyoak used a range of related problems to study how people use the knowledge gained from solving one problem to solve another similar problem. In particular, they were interested in how people find analogies between two problems as part of creativity, and how they come up with new ideas or new solutions based on existing knowledge.

Consider these two connected scenarios. The first one has a surgeon trying to remove a tumour from a patient using powerful rays without damaging the surrounding healthy tissue. The solution involves targeting the tumour with multiple weaker beams that converge to a point focused on the tumour. The second problem involves an army marching to attack a fortress, but it has to avoid triggering mines on the road that explode if too large a force crosses. The solution requires splitting the army up into many small groups who’d then converge on the fortress.

Consider these two connected scenarios. The first one has a surgeon trying to remove a tumour from a patient using powerful rays without damaging the surrounding healthy tissue. The solution involves targeting the tumour with multiple weaker beams that converge to a point focused on the tumour. The second problem involves an army marching to attack a fortress, but it has to avoid triggering mines on the road that explode if too large a force crosses. The solution requires splitting the army up into many small groups who’d then converge on the fortress.

Neither of these problems is well-defined, but you can see an underlying similarity – both problems involve splitting a stronger force into weaker ones that converge at a target.

Gick and Holyoak wanted to know whether, and how, their participants would use analogical problem-solving. To do so, the participants needed to notice the relationship and then map the corresponding elements between the original and the new problem (for example, fortress = tumour, rays = army and so on). They then needed to apply the existing solution to the new situation.

Gick and Holyoak found that people generally aren’t very good at noticing analogies unless they’re fairly obvious in the surface form of the story. Giving participants a hint that a relationship is present between the problems helps considerably. The task of mapping between problems is also quite demanding, because it can involve people holding several items in their working memory simultaneously. After the analogy is found, people have to implement it, which can also impose a big cognitive load.

Gick and Holyoak found that people generally aren’t very good at noticing analogies unless they’re fairly obvious in the surface form of the story. Giving participants a hint that a relationship is present between the problems helps considerably. The task of mapping between problems is also quite demanding, because it can involve people holding several items in their working memory simultaneously. After the analogy is found, people have to implement it, which can also impose a big cognitive load.

Revealing mental processes with the Gestalt school

Revealing mental processes with the Gestalt school Solving problems with computers and experts

Solving problems with computers and experts Considering cognitive research in learning

Considering cognitive research in learning Before cognitive psychology emerged in the mid-20th century, two prominent schools of thought existed on how people solve problems:

Before cognitive psychology emerged in the mid-20th century, two prominent schools of thought existed on how people solve problems: To illustrate his idea, Duncker provides this problem. You’re given a box of drawing pins (thumb tacks), a candle and a book of matches. Your task is to fix the candle to the wall. Try to solve it before reading on.

To illustrate his idea, Duncker provides this problem. You’re given a box of drawing pins (thumb tacks), a candle and a book of matches. Your task is to fix the candle to the wall. Try to solve it before reading on. We may have primed you to get the right solution by talking about seeing alternative functions for objects, but Duncker’s participants didn’t have this prompt. In general, a good tip for solving these kinds of problems is to question your natural tendency to make assumptions about how things can be used or how your actions are limited.

We may have primed you to get the right solution by talking about seeing alternative functions for objects, but Duncker’s participants didn’t have this prompt. In general, a good tip for solving these kinds of problems is to question your natural tendency to make assumptions about how things can be used or how your actions are limited. Computers provided a new way of thinking about thinking and were soon being applied to the study of psychology. In this new information processing approach, problem-solving was broken down into its basic constituent processes, which psychologists then simulated on a computer.

Computers provided a new way of thinking about thinking and were soon being applied to the study of psychology. In this new information processing approach, problem-solving was broken down into its basic constituent processes, which psychologists then simulated on a computer.

Brown and Burton’s work was pioneering in the 1980s, but such cognitive modelling of the learner is at the heart of much recent research in online education. The ability to test automatically students’ understanding and diagnose the reasons for their mistakes can greatly enhance online assessment. It can enable a computer program to be more responsive to students’ needs by identifying their misunderstandings.

Brown and Burton’s work was pioneering in the 1980s, but such cognitive modelling of the learner is at the heart of much recent research in online education. The ability to test automatically students’ understanding and diagnose the reasons for their mistakes can greatly enhance online assessment. It can enable a computer program to be more responsive to students’ needs by identifying their misunderstandings.