In the early hours of April 10, 1942 Japanese troops herded thousands of US and Filipino servicemen into columns on the southeast end of Bataan Peninsula near Mariveles. Other groups of prisoners were marched from Bagac on the far west side of central Bataan. They were about to begin what was to become the most notorious mass atrocity inflicted on US forces. The morning before, MajGen Edward P. King, Jr., commanding the Bataan Force, had surrendered 11,800 Americans, 66,000 Filipinos, and 1,000 Chinese-Filipinos to LtGen Homma Masaharu of the Japanese 14th Army. These men had been fighting ceaselessly for four months and for the last two had been on half rations or less. They were suffering from malnourishment, beriberi, extreme fatigue, malaria, and dysentery.

These troops, from a peacetime army, had never been taught how to conduct themselves in captivity and naively expected to be treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention. They had no idea what to expect and, with the short notice before their surrender, they had made no preparations.

The Japanese, regardless of assurances of humane treatment during surrender negotiations (one Japanese officer informed the Americans, “we are not barbarians”), were inadequately prepared for dealing with so many prisoners. They had expected the battle to continue and for many of the enemy to fight to the death as they would have done themselves. MajGen Kawane Yoshitake, transportation officer for the 14th Army, was given the task of planning the movement of the prisoners. He made preparations for only 25,000 detainees, not the eventual 79,000. Moreover, Japanese officers and soldiers had no idea of their obligations under the Geneva Convention and had been taught to despise Western protocols.

The Japanese “plan” was to move the thousands of already exhausted, starved, and ill prisoners north to Camp O’Donnell, a former Philippine Constabulary base with inadequate quarters and facilities. They unrealistically planned for the prisoners to carry their own rations and water. The problem was that virtually no rations remained, there was little to carry water in, and most US trucks had been disabled when the surrender was ordered.

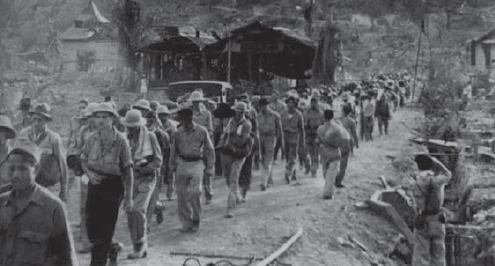

What became known as the Bataan Death March threaded up Bataan’s eastern coastal road through the sweltering jungle and sun-baked coastal plain. Surrendering troops had been formed up in scattered assembly areas and units broken up. Chains of command and unit cohesion disintegrated. Men were separated from their buddies and it soon became an every-man-for-himself situation. At different points some prisoners were given a can of food or a little rice. It is not known how many died by the end of that first horrible day. The exhausted prisoners slept in the open amid swarming mosquitoes and were driven to their feet at sunrise. Covering 10–15 miles a day, they were beaten northward to San Fernando, 63.4 miles from Mariveles. It was the dry season, but humidity was high and the temperature reached a scorching 104°F (40°C).

Besides these hardships, the brutalities inflicted on the men by their guards were horrendous and inexcusable. In addition to the lack food and water, no medical treatment was provided and the guards were often violent. Filipino civilians who tried to give prisoners food, water, and aid were driven off. Filthy water and even mud was lapped up from ditches and ruts by prisoners who soon suffered from stomach cramps and diarrhea. Prisoners falling out or unable to get to their feet after the rare breaks were shot or bayoneted on the spot, if not decapitated by sword-carrying officers and sergeants. Japanese troops aboard trucks passing the columns randomly bayonet-slashed and shot prisoners. Often, prisoners attempting to aid others were also killed. If a prisoner was found with Japanese money, mementos, or even items purchased before the war and marked “Made in Japan,” it was assumed that these had been taken from Japanese dead and so the bearer was butchered. Prisoners died of their previous wounds, dehydration, heat exhaustion, starvation, and from illnesses contracted earlier. In their weakened condition few were able to slip away.

It took five or six tortuous days, depending on where prisoners started from, to reach San Fernando, the men arriving between April 12 and 24. Over that time the wounded and sick still in the hospital were forced out on the death road as they were considered “recovered” by their captors. There the men were packed in boxcars: 100 into baking hot, fully enclosed cars designed for 40. They traveled 30 miles to Capas with more dying during the four-hour ride. A 7-mile march to Camp O’Donnell followed. All the time they had no idea how far they were to travel, where they were going, or when the nightmare might end.

Some 9,200 Americans arrived at O’Donnell with an estimated 1,200–2,275 dying en route.1 An estimated 42,800–50,000 Filipinos2 made it to the camp, with about 9,000–14,000 perishing. Approximately 2,200 Americans and 27,000 Filipinos died in O’Donnell, where mass burials were daily occurrences and some prisoners even died digging their own graves.

Some 79,000 American and Filipino troops were force-marched up the war-battered Bataan Peninsula for a torturous 64-mile nightmare. Thousands died owing to starvation, illness, fatigue, and outright murder. (US Army)

The Japanese had made virtually no preparations for the Death March, making little food and water available and not even permitting civilians to give it to the staggering prisoners. (US Army)

Contrary to popular perception, the prisoners captured in Corregidor did not take part in the Death March. Corregidor surrendered on May 6, 1942. On May 11, the 11,000 prisoners were loaded into three freighters bound for Manila. They were paraded through the streets to tout the Japanese victory, demonstrate America’s weakness, and humiliate the prisoners. Crammed into the Old Bilibid Prison3 near the dockyard for two or three days, they were taken by train to Cabanatuan City, and then marched to the Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Camp No. 1. Most US prisoners at O’Donnell were subsequently sent to the Cabanatuan camp, a former training facility of the 91st Philippine Division, between June and September 1942. Prior to serving as a military training camp, it had been a US Department of Agriculture research station dating from the 1920s. For a time it was the largest POW camp in the Philippines, housing 8,000 Americans. Within two months prisoners at O’Donnell began to be transferred to Cabanatuan as the former was gradually shut down. They endured a 7-mile march to Capas still in a weakened, if not a worse state than when they originally arrived. Packed once more into boxcars, they were railroaded to Cabanatuan City and marched 5 miles to the camp. Thousands of prisoners were subsequently sent from Cabanatuan to Japan, Manchuria, Formosa, Korea, and elsewhere in the Philippines as slave labor aboard the “hell ships.” A final group of over a thousand was shipped off in December 1944 just before the Americans landed on Luzon.4

As prisoners departed for unknown fates, one incident encouraged those remaining at Cabanatuan, most of whom were too ill and disabled to travel, many being amputees. Long fearing they were forgotten, in the middle of the month, they witnessed an air battle over the camp, in which a Japanese fighter was shot down. They could not immediately recognize the aircraft or the markings as the US had changed its nationality identification after the Philippines fell, but, using Red Cross parcel playing cards showing Allied aircraft, they identified them as new Navy Hellcats – American aircraft carriers were nearby.

After the first stage of the march, and a railroad ride packed in boxcars, the surviving prisoners marched 7 more miles to Camp O’Donnell. Here prisoners carry those too weak to walk in single-pole litters. Filipino guerrillas used this same type of litter to carry weak prisoners from the Cabanatuan POW Camp three years later. (US Army)

1 It must be noted the numbers of prisoners and their death rates vary widely between authorities. Seldom will two agree.

2 In July 1942 most Filipino prisoners were paroled, but many were simply transferred to labor units.

3 This was the old national prison and now served as the Manila City Jail; not to be confused with the New Bilibid Prison opened in 1940 in southeast Manila near the shores of Laguna de Bay.

4 In December 2008 the Japanese government extended an apology through its ambassador in the US to former American prisoners of war who suffered in the Bataan Death March.