CHAPTER 5

A LOVE OF MOUNTAINS AND MOTHERS: MONTENEGRO 1863(?)

On 12 July 2004, St Peter's Day, the Assembly of the Republic of Montenegro passed the Law on State Symbols and the Day of Statehood, which proclaimed the anthem of Montenegro to be the song with the title ‘O svjetla majska zoro’ (‘Oh, the Radiant [Bright1] Dawn of May’). The law set out the prescribed words of the anthem (Zakon 2004). As we shall see, these lyrics have since been a matter of controversy. ‘O, svjetla majska zoro’ is also the title and the first verse of an old Montenegrin folk song; whether its first published version is the one sung in a theatrical performance in 1863 (see below) is a matter of controversy too.

As we shall see below, this is not the first anthem of Montenegro. In 1870, the Prince of Montenegro, Prince Nikola, proclaimed another song, ‘To Our Splendid Montenegro’, written specially for him, to be the first state anthem of the Principality of Montenegro, which was at the time a de facto independent state. However, in 2004 Montenegro was still a federal unit of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, which used, by default, the Yugoslav state anthem ‘Hey Slavs’ (without lyrics) (see Chapter 1). Once the Union was, under the EU auspices, formed in 2003, it was proposed to combine the verses of ‘O svjetla majska zoro’ with the verses from ‘God of Justice’ (‘Bože pravde’) as its anthem. However, this proposal found no support among the major Serbian and Montenegrin parties and was denounced by the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church (Vreme 2004).

In May 2006, the government of Montenegro called for a referendum on independence. The referendum was supervised by EU representatives, who also set the threshold for a successful poll: 55 per cent of those voting had to vote for independence. The vote for independence was won with around 2,300 votes over the required threshold – those decisive votes all coming from two municipalities (Oklopčić 2012: 141). The pro-Union parties who opposed independence, mainly drawing on the votes of the Serbs (the citizens of Montenegro who declared themselves to be Serbs), demanded a recount but the EU-supervised Referendum Commission rejected their demand (BBC 2006). The independence of Montenegro was soon recognised by Serbia and by the end of June 2006 Montenegro joined the UN as an independent state.

This was not the first referendum on Montenegro's independence. In March 1992, in a first referendum, 95.94 per cent of those voting voted for Montenegro to remain in Yugoslavia with Serbia (Andrijašević & Rastoder 2006: 191). It was the same Prime Minister, Milo Djukanović, who in 1992 campaigned for Montenegro to remain in Yugoslavia and in 2006 for its independence.2

Some of the opposition parties that in 2006 opposed independence – the People's Party, Democratic Serbian Party, Serbian People's Party – also objected to the text of the anthem and in 2004 refused to vote for the Law on the State Symbols. In addition, some Muslim and Albanian deputies, who did not oppose independence, objected to the use of religious symbols and the phrase ‘our mother Montenegro’ (PCNEN 2004). The controversy over the text of the anthem continues and will be discussed later. A part of the current controversy over the anthem text concerns its origins.

From bravery to eternity

Prior to the building of the National Theatre building in Beograd, Serbia in 1868, the theatre repertoire was dominated by patriotic pieces ‘with singing’ which we could perhaps call semi-musicals. As in pre-unification Italy and Germany during the nineteenth century, theatre was one of the principal outlets for public displays of patriotic feelings, not only through dramatic representations of glorious ancestral battles and deeds, but also through singing. Unison in song is both an apt expression of patriotic feelings and an assertion of an identity in common.

Two of the songs from the nineteenth century patriotic semi-musicals proved to have an unexpectedly long life, perhaps because of their efficacy for nationalist purposes. ‘Oh, the Radiant Dawn of Bravery’ sung in 1863, and ‘God of Justice’ sung in 1872 seemed to have provided the thematic bases or templates for, respectively, the state anthems of Montenegro (2004) and Serbia (2006). As might be expected, the lyrics adopted as official texts for state anthems in the twenty-first century have differed considerably from the stage versions first performed in the nineteenth century; this is one of the reasons why many Montenegrin scholars would not see ‘Oh, the Radiant Dawn of Bravery’ as a template for the current anthem.

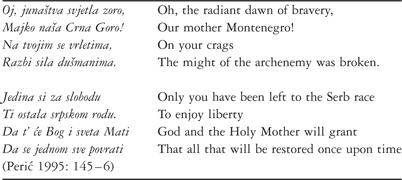

‘Oh the Radiant Dawn of Bravery’ was sung in the 1863 play entitled Battle of Grahovo or blood feud in Montenegro. This was ‘a play about brave men (junačka), in the three parts, with singing’. No text of the play is preserved, nor for that matter do any other works by its authors, Jovan Car and Obrad Vitković. However, a compilation of theatre songs offers the following lyrics.

This is a song about the country whose mountains and their associated bravery have defeated the archenemy (the Ottomans) and left a space for the Serb race to enjoy freedom. The mountain-assisted defence of freedom and independence is, as we shall see, one of the central themes of the lyrics of the current anthem. The conviction is that freedom, and by implication an independent state, will be restored in time to come by the will of God and the Holy Mother. In 1863, Serbia was not yet fully independent because several Serbian towns as well as its capital were still garrisoned by the Ottoman military and Serbia paid tribute to the Ottoman emperor.

This short song introduces two historical stories that were widely popular at the time. The first is that during the long period of Ottoman rule over the Balkans, from the battle of Kosovo in 1389 until the granting of autonomy to the Principality of Serbia in 1830, the only part of the Serb-populated territory free from the Ottoman rule was the mountainous core of Montenegro or the Black Mountain. The second story is that the reason the Ottomans were never able to occupy and hold this part of Montenegro was because of the impassable mountains – the ‘crags’ of the song – and because of the unwavering resistance of the mountain tribes of Montenegro who upheld their warrior ethic and never accepted the ‘Ottoman yoke’.

At the time of singing in 1863 these stories were not contested or at least there was no record of any contestation. Yet they rest on a piece of a highly contested national identification according to which the population of ‘our mother Montenegro’ belongs to the Serb race (srpski rod) or are a branch of the Serb nation; in short that Montenegrins are Serbs. Only if Montenegrins are of the Serb race, could ‘our mother Montenegro’ be the only place where the race could enjoy liberty: there were no other Serbs, from Serbia or any other part of the Balkans, living in Montenegro at the time. This identification of Montenegrins with Serbs is officially discredited and rejected at the time of writing in 2013: the government of Montenegro and a large part of its population now hold that Montenegrins are not Serbs but rather a separate nation.3 At the moment no scholar who identifies themselves as Montenegrin only (and thus not as a Serb) would consider ‘Oh, the Radiant Dawn of Bravery’ to be the original template of the current text of their anthem.

And yet the 1863 song, however pro-Serbian it may appear to be today, introduces both the opening verse (in which ‘bravery’ stands for the later version ‘May’) and the two themes of the current anthem of Montenegro as the mother of the singers of the song and of Montenegrin mountains as a defence of freedom from the ‘foreign yoke’. In contrast to the 1863 song, the current anthem makes no reference, explicit or oblique, to the Serbs or their freedom. Montenegro's union with Serbia from 1918 to 2006, and the Montenegrins' long historical association with the Serbs, is understandably given no mention in the anthem, which was introduced by the government that had been planning to secede, for ever, from the union with Serbia.

Yet the anthem of Montenegro, proposed in 2004, has striking thematic and textual resemblances to the nineteenth-century song that identified Montenegrins with the Serbs and expressed the hope that the latter would restore their independence. So how could a song identifying Montenegrins with Serbs have given rise to an anthem that rejects any link, present or future, with the Serbs?4 As we shall see, by removing any reference to the Serbs and by introducing new themes that steer Montenegro away from any neighbouring or related nations, the current text of the anthem focuses solely on Montenegro and proclaims Montenegro to be everlasting – that is, an independent state for all eternity.

Of love and of honour: Montenegrins and their mother or motherland

The theatre song shares at least one rather general feature with the current anthem of Montenegro: both are self-congratulatory songs in which the singers congratulate first of all their motherland and, by implication, themselves on having such a wonderful and eternal motherland.

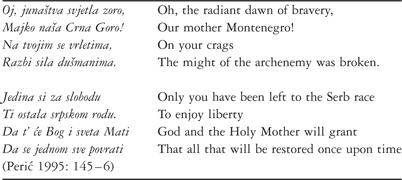

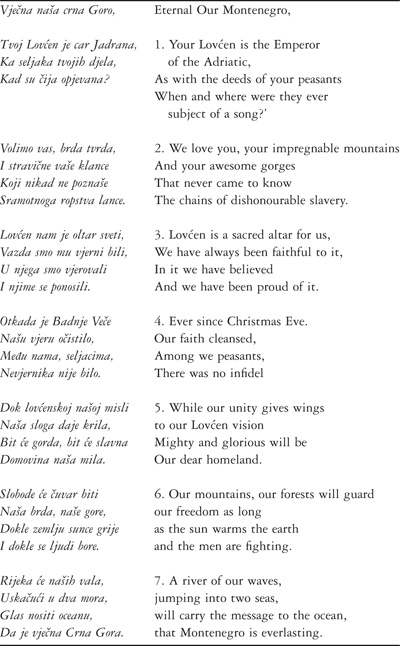

The first two stanzas of the anthem introduce the two major themes of motherhood and its honour as well as the firm mountains that preserve the country's honour or freedom.

These stanzas combine the imagery of dawn, mountainous landscape and freedom from foreign occupation in a manner similar to that of the 1863 song. The radiant dawn leads to the statement of ownership and motherhood: Montenegro, the land, is the mother of the singers-in-unison, who are referred to only as ‘we’. The name of the land ‘Crna Gora’ means ‘the Black Mountain’ and the English ‘Montenegro’ is in fact an Italian translation of its original. The image of motherhood is further reinforced by the metonymic assertion that we, the singers, are the sons of the Black Mountain's rocks (which were named ‘crags’ in the 1863 song). The assertion reinforces the desired and often repeated representation of the singers-in-unison, the Montenegrins, as hardy, resilient and brave ‘mountaineers’ or sons of the mountains. The assertion may suggest yet another – one may also say stereotypical – representation of Montenegrins as male chauvinists. As the recent chairwoman of the Montenegro's National Assembly noted, there is no gender equality in the anthem and the offspring of the rocks are here emphatically sons and not daughters (Vesti Online 2012).

Being born of rocks, the sons dutifully love their life-givers, the mountains and gorges that dominate the landscape of their mother, the Black Mountain. The mountainous landscape thus dominates the first stanza as it dominates the land of Montenegro: it is the Black Mountain that gives birth to the sons who, in the second stanza, love its firm mountains and awesome gorges. Their love is not only motivated by their putative origin because these gorges have avoided dishonourable slavery. Since these very sons are also the guardians of the honesty of their mountainous mother, their love for the mountains, it is implied, is motivated by their pride in their mother's honour. The sons of the gorges and mountains love their mother because they feel proud of her honour, which rests in never have been subject to foreign rule or foreign slavery.

In contrast to the 1863 song, the anthem makes no mention of the defeat of enemies or archenemies. Instead, the defeat of enemies is replaced by a thematically related topos – escape from, or rather the avoidance of, slavery. Unlike defeats, one cannot leave a nation's bravery to the past. But why was ‘bravery’ in the first verse of the 1863 song, replaced with ‘May’, the name of a month, in the anthem text of 2004?

Danilo Radojević (2011: 378), an advocate of separate and unique Montenegrin identity, points out that the Serbian poet Sima Milutinović-Sarajlija greeted Montenegro as ‘a Yugoslav dawn’5 and, later, Ljubomir Nenadović6 once again called Montenegro ‘a Serb dawn’.7 Thus the simile of Montenegro as a dawn, as a beginning of a new and happier era for the South Slavs or for the Serbs, had been established in Serbian poetry in the first half of nineteenth century. ‘Bravery’ is certainly less politically charged than either ‘Serb’ or ‘Yugoslav’ but it may sound too conceited; ‘May’ is possibly the most neutral word to describe the happiness that a dawn may bring. According to Rotković (2011: 387), ‘the [word] May was chosen not only as a month of flowers and spring but because all other names of months, except for June and July, are multisyllabic and could not fit into the decalic verse’. In his view, the first verse of the folk song ‘Oh, the radiant dawn of May’ is a mere preamble introducing the rest of the song, which, as he notes, was sung at the beginning of any collective celebration and group singing in Montenegro (Rotković 2011: 385). Rotković and other scholars (for example, Marković 2011) all agree that the first two stanzas of the current anthem come from a folk song (and not from the theatre song) and so have no political message – unlike the poem ‘Our Eternal Montenegro …’ by Dr Sekula Drljević, which we shall discuss below.

Of unity, glory and eternity

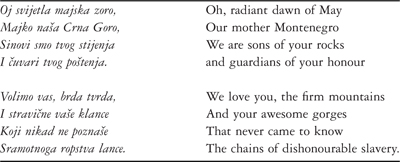

In contrast to the apolitical first two stanzas, the third and fourth stanzas introduce a few rather obvious political messages.

The third stanza introduces the topos of might and glory via that of unity. All three are standard concepts and topoi of anthemhood: rare is an anthem that does not attribute to the subjects of the anthem one or more of these attributes. Most frequently it is the motherland/fatherland/homeland that is mighty and glorious while the singing nation is united. In most anthems, glory is dependent on might, and both glory and might are dependent on the unity of the singers/the nation. The unity of the singers confers might on the land/state/sovereign and this naturally (at least in the world of anthems) brings glory.

As we can see, this is the pattern followed in the current anthem: the unity of the singers gives an élan (‘wings’) to their Lovćen vision and this unity, permeated by a specific vision, naturally leads to their dear homeland becoming both mighty and glorious. The dear homeland, it is assumed here, is the mother of the singers, the Black Mountain the singers love. Thus the image of the mother and its mountainous landscape merges with the image of a mighty and glorious country or state that is also a dear homeland. The seemingly mysterious reference (in the first line above) to the ‘Lovćen vision’ is explained below.

The final stanza introduces another staple of anthem landscape – rivers – and yet another staple anthem narrative – eternity of the fatherland/motherland/homeland. In the last stanza, Montenegro's landscape is recruited once again in the service of the anthem but this time only as a conveyor of a message, ‘a voice’. In comparison with the rocks in the first stanza and the mountains in the second, the unnamed river in the fourth, a mere messenger, appears to be somewhat demoted. The rocks play the (metaphorical) role of the mother of the nation and the mountains are the object of love and devotion while the river is a bringer of tidings.

Like the rocks or the mountains in the first two stanzas, the river, the two seas and the ocean are not identified in this song and so it quite unclear whether the river and the seas are metaphors for might, the most efficient conveyers of messages, or stand for a particular river in Montenegro and the sea or seas on Montenegro's shores. Even if these are just metaphors, the meaning of the last stanza is clear – the message needs to be disseminated in the most effective way to the outside world – and a river will do this better than any other ‘natural’ or non-human element of Montenegro's landscape. Another interpretation of the last stanza is explored in the next section in the context of Dr Drljević's poem ‘Our Eternal …’ and its resemblance to the Croatian anthem ‘Our Beautiful Homeland’.

But what is the message that the river needs to carry? At first it is a most unexceptional message, at least for an anthem, that ‘our dear homeland’ is eternal. In general, anthems do not allow any temporal limitations on homelands: however mortal the singers of anthems may be, their homelands/motherlands are not restricted in their putative duration. In the realm of anthems, all homelands are eternal. As for its anthem-content, the message the river needs to carry is thus unexceptional.

Yet in spite of being unexceptional, this is key political message of the anthem: that the independent state of Montenegro will last for ever. So Montengrins' love of their mother, of their dear, mighty and glorious motherland, and their élan and their unity (all common anthem themes) lead us to the last but most important message: from 2006 the independence of Montenegro is to be perpetual. There will be, the anthem tell us, no more unions of Montenegro with any other state and Montenegro will be eternal as an independent state.8

It is not the conveyance of the message but the message itself that matters: never again will Montenegro be annexed or unified with another state, certainly not with Serbia from which it seceded in 2006. By implication, never again will Montenegrins be a branch or ‘tribe’ of another nation. The assertion of eternality is thus a rejection of any possible dilution of Montenegro's separateness.

In a summary, the song moves from the assertion of belonging and devotion to an assertion of unity and Montenegrins' might and glory, ending with an assertion of Montenegro's eternity-in-independence. The honorific concepts of belonging, love, unity, might, glory and eternity are common anthem elements. Whether or not this mix is essential to anthems in general, the very frequency of its repetition in various anthems suggests that this is the right mixture of honorifics with which to express devotion and to extol the virtues of the anthem's singers and of their homeland.

Having noted the staple features of the anthem, let us now explore one of its unique features – the reference to the ‘Lovćen vision’ or, in a more literal translation, the ‘Lovćen thought’. Lovćen is the towering mountain on the coast of Montenegro, overlooking the bay of Kotor, on the Adriatic Sea, on the top of which the greatest Montengrin poet and prince-bishop Petar Petrović II Njegoš lies buried.9 Since the poet statesman is buried there, ‘the Lovćen vision’ appears to refer, in a rather oblique manner, to Njegoš' own thought or vision. So what is Njegoš' vision? According to the current President of Montenegro Filip Vujanović:

Njegoš' poetic words and thought represent the cultural, historical and spiritual synthesis of Montenegro, the fundaments of our language and identity, which makes us visible and respected in the space of Europe (Vujanović 2013).

This excerpt does not explain what Njegoš' or Lovćen vision consists of yet it highlights its importance as the source both of national identity and national pride in the achievements of Montenegro and Montenegrins. As the source of their identity, language and pride, Njegoš' thought should indeed give Montenegrins the élan that brings might and glory to their homeland (and possibly, as Vujanović seems to suggest, their entry into the EU/Europe as well).

Montenegro and its anthems: A brief history

From the Middle Ages until the present, Montenegro's society in the core mountainous region of the ‘Old Montenegro’ has been based on clans identified by a name resembling a personal surname – Vasojevići, Belopavlići – and by the territory the clan inhabited. The clans are called ‘tribes’ (‘plemena’). In the continuing conflict with the Ottoman Empire, which claimed sovereignty over the whole of Montenegro, the clans provided the fighters and their leaders. As the conflict intensified in the early seventeenth century, the Eastern Orthodox bishops from the monastery in Cetinje became leaders of these clans fighting against the Ottoman rulers and endeavoured to unite them politically. In 1696, the family Petrović Njegoš became recognised as the hereditary holder of the title Bishop-Prince (‘vladika-knez’), which was transferred from uncle to nephew (since Eastern Orthodox bishops are celibate). In 1852, the Bishop-Prince Danilo I Petrović, who succeeded to Petar II Petrović Njegoš, abandoned the title of Bishop and was recognised by the Russian court as the Prince of Montenegro. Following his assassination in 1860, his nephew Nikola was proclaimed the Lord (Gospodar) of Montenegro (Andrijašević & Rastoder 2006: 51–93).

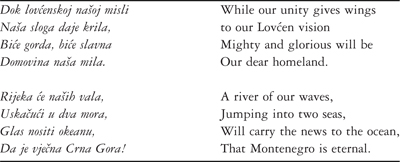

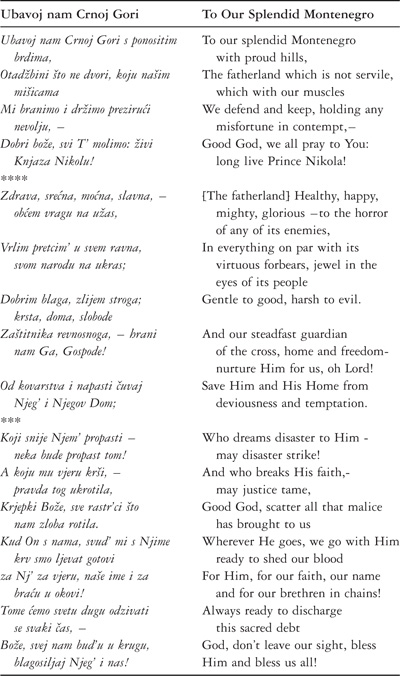

The following poem, ‘To Our Splendid (or Beautiful)10 Montenegro’ (‘Ubavoj nam Crnoj Gori’) was published in 1865 in a journal in Montenegro and was performed for the first time as a song in 1870, in the presence of Prince Nikola, in the main reading room of the capital Cetinje:

Having heard the song performed, Prince Nikola proclaimed it the state anthem of the Principality of Montenegro. The Principality gained international recognition of its independence in 1878 at the Congress of Berlin and in 1910 Prince Nikola proclaimed it a kingdom with himself as king.

The author of the poem was the Prince's secretary, Father Ivan Sundučić, a Serb born in Bosnia, and educated as an Orthodox priest in a monastery in Croatia. By 1870 he was a well-known poet of occasional verses celebrating events and renowned personalities of the Slavs, in particular South Slavs. He was also a well-known Pan-Slavist whose large poetic opus, apart from this song, is now largely forgotten.

This poem was modelled on the Russian Imperial ‘God Save the Tsar’ and the Austrian equivalent, all of which follow the arch-model of all prayer-anthems, the British ‘God Save the King/Queen’ (see Chapter 4). The Serbian equivalent, praying to God to save the Serbian Prince Milan, was performed for the first time on the Beograd stage two years later. The destinies of these two prayer-anthems differed greatly: the Montenegrin one lost its anthem status in 1919 as Montenegro became part of a larger state of the South Slavs (see below) while the Serbian anthem continued until 1945 as a part of the composite anthem of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and was then resurrected in 2004 and constitutionally entrenched in 2006 as Montenegro's secession left Serbia once again an independent state.

The government of the Republic of Montenegro was happy to resurrect the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Montenegro as well as its royal standard as the state symbols of the newly independent Republic. So why not resurrect its royal prayer-anthem as the Serbian government did? It is difficult to find a conclusive answer, but one reason might have been that the royal anthem faced a fierce competition for anthemhood. There were another two national songs also competing for the title (Vreme 2003). In addition to ‘Oh, the Radiant Dawn of May’, there was also ‘There, over there …’.

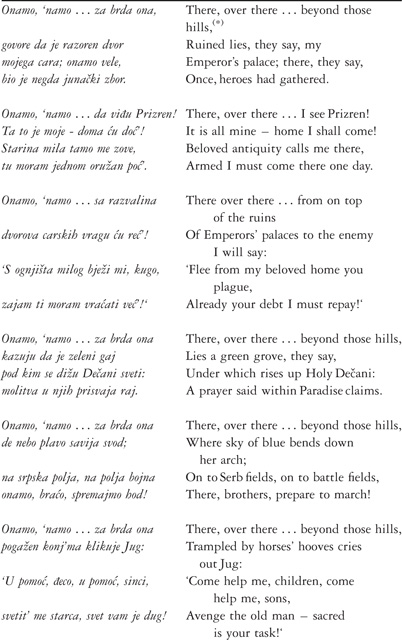

This is a poem of the recovery of a lost empire – the empire of Dušan, the first and only Serbian emperor – and of the recovery of lost glory. Both vanished in the mists of medieval history. The poem is full of references to Kosovo and Metohija, the site of the historic battle of Kosovo of 1389 against the Ottoman Islamic forces. It is also full of references to folk poems about the battle in which the Serbs allegedly lost their kingdom and the cream of their nobility. Prizren is a formerly royal city of that region and Dečani is a large medieval monastery there. Jug is the name of one of the heroes of the Kosovo battle epic and so is Miloš, who is said to have slain the Ottoman sultan on the battlefield. This is thus a very pan-Serb poem expressing the desire for the recovery of a Serb kingdom that was reputed to have included Montenegro. But – and it is a huge but for a candidate of an anthem of an independent Montenegro (in the making) – there is no mention of Montenegro in the poem. Not only that, this poem does not even suggest that there is a Montenegro as a separate entity or region.

The poem's author was Prince Nikola himself. It was published for the first time in 1867 in Danica a popular Serb magazine in Novi Sad, which two years previously also published several candidates (all unsuccessful) for the Serbian anthem (see Chapter 4). At the time of its publication, the poem called for the liberation and secession of Kosovo from the Ottoman Empire and was thus not quite suitable as a state anthem of a small and still unrecognised state bordering on the Empire. However, it was a highly popular national song sung on many official and unofficial occasions and its singing was for obvious reasons occasionally banned in the Serb-populated parts of the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires.

One can now see why in 2004 the ‘Oh, the Radiant Dawn of May’ would be considered preferable to these two competitors:11 one was a royal prayer song and another the king's own nostalgic song yearning for the recovery of the lost pan-Serb state and pan-Serb glory. The government of Montenegro was looking for a song that would implicitly or explicitly justify the separation of its singers, Montenegrins, from the Serbs with whom they had been associated, in poems and in song lyrics, for several centuries. The dynastic symbols of the Montenegrin Petrović dynasty (the flag and the coat of arms) served this purpose well, asserting a separate state identity and history as a small principality and later kingdom, independent of Serbia. Yet the royal prayer song mentioned Montenegro only in its first line and had over-all very little to say about Montenegro or its people, apart from the generic themes that they were a splendid people and that they should be healthy, happy, mighty and a terror to their enemies.

The royal prayer anthem also focuses on the royal person. It does so much more than its Serbian counterpart. As we saw in Chapter 4, the latter presents a wide panorama of the Serb land and its history and says nothing about the desired or existing attributes of its ruler. This is what made it so easy, and politically almost imperceptible, in 2004 to replace the king image with the Serb lands. Any attempt to do the same with its Montenegrin equivalent ‘To our Splendid Montenegro’ would require not only a deletion and/or modification of a substantial part of the poem but a significant poetic inventiveness.

Even more important was the absence, in these two songs, of any way of distinguishing Montenegro from Serbia and Montenegrins from the Serbs. Neither the royal song nor its nostalgic give-us-back-our-glory competitor offer any suggestion as to how do this. Given that the principal theme of ‘There, over there …’ is pan-Serbism and its prior glory, there is no way that it could offer any such suggestion. In the song, the Montenegrins are simply assumed to be part of Serbdom.

In 2004, the government of Montenegro needed a state anthem as a symbol of separate statehood and separate nationhood as well and neither of the two competitors could fulfil this role, not even with substantial modifications. So where then to find a poem or a song that would suggest, or even better, express the separateness of the Montenegrin nation and the independence of Montenegro itself?

The poem of Montenegrin exceptionalism: Of love and of eternity

Until October 1918 Montenegro was a state independent from Serbia. The history of Montenegrin separatism, as one would expect, starts at the time of its unification with Serbia. Once the occupation forces of Austria-Hungary left and were replaced by the forces of the Entente, including those of Serbia, the pro-Serbian unification faction in Montenegro, supported by the victorious Serbian government, quickly organised indirect elections for a national assembly, which was to vote for the dethroning of the Petrović dynasty and unification with Serbia. This move was actively opposed by a group of citizens in the capital Cetinje and surrounding countryside. This group's candidates were listed on green paper while the pro-unification ones were listed on white paper: from then on the ‘Greenies’ (Zelenaši) was a general name given to any political group or individual that opposed unconditional unification with Serbia. In spite of the opposition of the Greenies, in November 1918 the 160 delegates of the Grand National Assembly unconditionally unified Montenegro with Serbia, dethroning the aging King Nikola who was stranded in France at the time. An armed rebellion led by the Greenies broke out on 24 December 1918 but was quickly suppressed by local Montenegrin forces leaving 16 of the rebels dead (Andrijašević & Rastoder 2006: 162); the Greenies' resistance in the countryside continued sporadically until 1924.

From then on the main political opposition to the loss of Montenegro's autonomy came from the Montenegrin Party or the Montenegrin Federalist Party, which included not only the Greenies but also some erstwhile supporters of unification with Serbia who had become disillusioned after the unification. Among the latter was a lawyer and amateur poet educated in Croatia, Dr Sekula Drljević. His persistent criticism of the unitary and centralising policies of the Beograd government singled him out as one of the most vocal and consistent opponents of the Serb political dominance and the Serb royal dynasty in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In April 1941, following the defeat and surrender of the Royal Yugoslav military to the Axis forces, the Italian army occupied Montenegro and the Italian occupation authorities called an assembly on 12 July 1941, St Peter's Day, which was to proclaim an independent Montenegro under Italian protection. The chief speaker was Dr Drljević. A mass armed rebellion broke out on the next day, organised both by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and Serb/Yugoslav royalists, and was soon transformed into a civil war. Having quickly regained control of most of Montenegro through a large counter-insurgency operation, the Italian governor appointed Drljević the commissar for home affairs of the occupied Montenegro only to dismiss him in November 1941 and deport him to Italy. From Italy Drljević travelled to Croatia, which was ruled by a Nazi-installed pro-fascist Ustashe regime. Until 1944 he lived in Zemun, an Ustashe-held city near Beograd; it is in Zemun that he wrote The Balkan conflicts published in 1944 in Zagreb. As the Red Army and the Communist-led Partisans neared Beograd, he moved to Zagreb where he established the Montenegrin State Council, attempting to re-establish an independent Montenegro under German protection. In April 1945, from the retreating Montenegrin royalist Chetniks, he also formed a Montenegrin army under his overall command (Adžić 2011: 133). In November 1945 in Judengburg in Austria, members of this Montenegrin army murdered him and his wife before themselves being turned over to the victorious Communist-led Yugoslav army (Andrijašević & Rastoder 2006: 226). In 1946, in Zagreb, the Communist-controlled Commission on the war crimes of the occupiers and their collaborators, obviously unaware of his death, proclaimed Dr Drljević a war criminal (Adžić 2011: 185).

Since the late 1990s, Drljević has been rehabilitated in Montenegro both as a politician and a political thinker. In his major work The Balkan Conflicts 1905–1941 he argued that Montenegrins are not of the same origin as the other Slavs, such as Serbs, but instead come from the ancient Illyrians and ‘the Illyrian blood together with their geopolitical position and history, continued to be the creator of their culture’. They have a thousand year old continuity of an independent state and an ‘ethnic and ethical uniqueness’ (Drljević 1944: 163). From this Drljević concluded that

[t]he state independence of Montenegro is for the Montenegrins not the question of their vanity but a necessary presupposition for the maintenance of the purity of their race and of their culture (Drljević 1944: 166).

Perhaps Drljević's conclusion could be translated into the currently more acceptable terminology of national identity. So translated, his argument would be that the independent state of Montenegro is necessary if Montenegrins are to preserve their national identity as authentic and genuine.

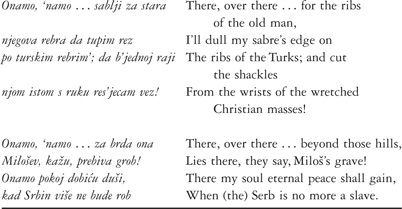

The book, which ends with the above celebration of Montenegro's independence, is prefaced with the poem entitled ‘Our Eternal Montenegro’,12 which celebrates Montenegro's eternity:

Sekula Drljević claims authorship of the poem at the end of the poem, removing any doubt of its folk-song origin. In 1936, he published an almost identical poem in Podgorica in Montenegro under the title ‘A Montenegrin peasant dance (kolo)’ and in Zagreb under its present title ‘Our Eternal Montenegro’ (Radojević 2011: 381–2).

Stanzas 5 and 7 of Drljević's poem are identical to the last two stanzas of the current anthem text. In view of this, it is understandable that the following questions have been raised and vigorously debated in the Montenegrin media.

Where does the anthem come from? Who wrote it?

There is a considerable debate among scholars as well as among Montenegrin politicians, Orthodox clergy and the popular media concerning the following two interrelated questions:

The first question is still a major issue in party politics in Montenegro. At the time the anthem was proposed in 2004, the Patriarch Pavle of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Beograd, in a highly unusual open letter, requested the Montenegrin government not to use the text of the current national anthem on the ground that the text originated in Drljević's poem and that Drljević was, in his view, a war criminal and a quisling (PCNEN 2004a). A similar view of Drljević and of the national anthem was endorsed at the time by the Serb Democratic Party, People's Party and Serb People's Party – all of which claimed to represent those citizens of Montenegro who felt that they were Serbs and thus rejected Drljević's view of Montenegrin uniqueness (PCNEN 2004). In the opening session of the Assembly in November 2012, 11 members of the Democratic Front, the largest opposition bloc, walked out before the anthem was performed; most of them belonged to the New Serb Democracy, the party that took the view that Drljević was a war criminal (BIRN 2012). In some cases, at local events, the organisers and participants still sing only the first two stanzas, those supposed not to originate in Drljević's song. Even the current President of Montenegro, Filip Vujanović, a member of the ruling party that originally proposed the anthem, has on several occasions expressed unease with the current text, in particular with the last two stanzas (which are identical with those of Drljević's poem) (RTV 2011).

In this debate, some scholars and politicians have argued that Drljević simply used a folk song as his model and that the current anthem is based not on his poem but on that earlier text that he used. Therefore, the current national anthem need not be associated with Drljević at all and it should thus not be seen as politically objectionable. In addition, no evidence has been adduced, at least not in scholarly literature, to identify any folk song containing text similar to the two last stanzas of the national anthem that are identical to the fifth and seventh stanzas of Drljević's poem.

The major question is then: how much does the current national anthem borrow from Drljević's poem ‘Our Eternal Montenegro’? Some scholars hold that only one stanza – the last one – is from Drljević poem while others claim that stanzas 1, 2, 5 and 7 from Drljević's poem were all transferred into the current anthem but that the first stanza of Drljević's poem had undergone some significant changes (Radojević 2011: 380). The latter view in fact implies that the whole of the current national anthem originates in Drljević's poem and that Drljević is thus the principal author of the national anthem. In contrast, the Polish literary scholar Boguslav Zielinski (2010: 27) as well as other Montenegrin scholars maintain that the two last stanzas (third and fourth) of the current anthem were written by Drljević while the first two originate in a folk poem. This appears to be the view of those citizens of Montenegro who refuse to sing the last two stanzas and of the current President of Montenegro, Filip Vujanović who feels uneasy about these two but not the others.

The last two stanzas: Of which anthem do they remind us?

There are indeed a few similarities between the two last stanzas of the current Montenegrin anthem and several verses from the current Croatian state anthem ‘Our Beautiful Homeland’, discussed in Chapter 2.

In the Croatian anthem the three rivers – Sava, Drava and Danube – carry the ‘voice’ or the ‘message’ that the Croats love their homeland to the ‘deep blue sea’. In the Montenegrin anthem (and in Drljević's poem) it is a single but unnamed river and its waves that carry the message to the ocean, first jumping into two seas. Unlike the named rivers that flow through Croatia, the identity of this Montenegrin river is rather mysterious. As a Montenegrin scholar noted ‘our longest river which directly flows into the sea, Sutorina, is around five kilometres long; during the summer it cannot, with its waves, water even a single garden and at its confluence into the sea it almost completely dries up creating smelly marshes and sources of mosquitos’ (Marković 2011: 396). Leaving aside the power of such a river to carry any requisite messages, what are the two seas to which the river flows? The Sutorina flows only into one sea. No scholar or anthem singer, at least to our knowledge, has even tried to identify the river or the seas to which the poem refers.

Further, the last line of the third stanza calls Montenegro ‘our dear homeland’ (‘domovina naša mila’) while the Croatian anthem in its first stanza uses an identical phrase to identify Croatia. In the second stanza, the Croatian anthem attributes glory to the dear homeland, and once again the same word ‘slavna’ is used in the third line of the third stanza of the Montenegrin anthem.

The analysis of the two stanzas most likely written by Dr Drljević reveals two peculiar features: the appropriation of a specific item of landscape without means of identification, and the use of identical phrases to describe the homeland as those used in the anthem of the state very close to Montenegro. Why would a nation wish to represent itself through reference to an unidentifiable aspect of landscape? Why would a nation also choose to represent itself with the words used in another state's well-established anthem? No answers to these questions have as yet been suggested.

The national anthem and the political divisions in Montenegro

However, these are not the only questions that arise in regard to this anthem. One of the other unresolved questions is: what is the purpose of introducing an anthem that will divide instead of uniting the citizens of Montenegro? The ostensible aim of national anthems is to unite its singers, preferably into a single nation. Yet, since it was proposed in 2004, the current text of the Montenegrin anthem has done just the opposite. It has led an acerbic public controversy and a political division within Montenegro that reflects the national cleavage between those who believe that Montenegrins are in some way or another related to the Serbs and those who reject this view and assert Montengrins' unique national identity. As we have seen above, some anthems may have this kind of divisive effect in states which are the home of different and separate national groups. If an anthem is a national anthem of one of these groups, the other group or groups may simply reject it as not theirs. Since most European anthems date from the nineteenth-century era of national revival they are for the most part national songs – songs extolling the virtues of, or calling on, a single nation. There are only a few national songs that are supranational. ‘Hey Slavs’ is, as we have seen, a rare example of this kind.

The current lyrics of the anthem have both led to an ongoing political controversy concerning its alleged author and exacerbated the division within the Montenegrin national group between Serbophiles and Montenegrin separatists. Although the anthem itself did not bring about the cleavage between these two groups, which has a long-standing history going back at least to 1918, it did increase the division.

There are two ways in which the anthem has done this. The first is obvious: the author of the two stanzas has been perceived (whether justifiably or not) as a war criminal and fascist. This argument taints those who advocate the anthem and the independence of Montenegro, and paints them as people who are tolerant of fascism or even pro-fascist. The pro-Serb politicians in Montenegro make two types of claims against Drljević. First, they claim that he sent thousands of innocent Montenegrins to their death when he collaborated with the Italian occupiers and later with the pro-fascist Ustashe regime.13 Second, they claim that he was a Nazi and fascist who shared the anti-Serb ideology of the Ustasha regime in Croatia where he lived from 1941 until 1945. In many public statements these two claims are conflated so that Drljević is proclaimed as a war criminal because of his alleged adherence to a fascist ideology. Many anthem critics suggest that in accepting his two stanzas, the pro-anthem parties/individuals are in effect saying that in Montenegro it is acceptable for the author of the national anthem to be a fascist or a war criminal.

In response to these arguments, those who advocate the anthem often argue that the question of whether the author of the two stanzas was a war criminal or not is irrelevant: one's anthem should not be tied to the personality of its alleged author (Rotković 2011: 388). Moreover, they argue that that the Drljević poem was first published in 1936, at which time he had no association with the Ustasha movement or with the future occupiers of the country. Further, some scholars argue that Drljević was not a war criminal, since the Communists' charges of war crimes against him were politically motivated and never tested in court. Indeed, they claim he sent no one, let alone thousands of people, to their deaths (Adžić 2011: 185). It is also argued that in his works he never espoused either the Ustasha, or fascist, ideology of any kind. He was only a nationalist committed to the independence of Montenegro who made a serious mistake in seeking support among Axis powers and their local supporters (see Adžić 2011: 184; PCNEN 2004c; Radejević 2011: 382).14

The continuing political controversy could easily be ended by simply removing the two offending stanzas from the anthem and leaving the two first uncontroversial stanzas together with the title. There is a history of such successful accommodation strategies elsewhere, for anthems that appear to be tainted, but for which an attachment remains. The continuing use of ‘Deutschlandlied’ in Germany is the most obvious European example (see Chapter 3). For such a change in Montenegro, that is a change of the 2004 Law on State Symbols, a simple majority vote in the National Assembly would be sufficient. And yet, for many of the pro-anthem advocates, the removal of the two stanzas from the anthem would appear to be a defeat of their vision of Montenegro's independence. Since they believe that Montenegro should be independent forever and not enter any state union with another state (except, of course, the EU), the explicit removal of such an aspiration from the anthem would, for them, mean the rejection of their vision. This vision of Montenegro as everlastingly independent overrides any other concerns, including the political views and deeds of the author and the unity of the nation-singing-in-unison. The apparent paradox here is that those who believe in the inviolable separateness of the nation from its neighbour put the assertion of separation ahead of the possible unity that may be found in singing.

In fact, the two stanzas are, in this public debate, often put forward as a test of Montenegrin national identity and national loyalty: those who reject the two stanzas are at times branded as ‘anti-Montenegrin’ (‘anticrnogorski’). In retrospect, it looks as if the party leaders, led by the long-serving Prime Minister Djukanović, who from 1996 onwards started to seek separation from Serbia, introduced the text of this anthem in 2004 for two related purposes: as a rallying point for all those who favour separation and the independence of Montenegro and as a test of loyalty for those who reject the separation. As the referendum on independence showed, a large number of citizens of Montenegro – slightly fewer than 45 per cent of those voting in the referendum – rejected this option. In their view, Montenegro should not be independent from Serbia and thus they have far less inclination to sing the last two stanzas. The division between pro-anthem and anti-anthem groups mirrors to some extent the division between pro-independence and anti-independence segments of the Montenegrin electorate. The above controversy about Drljević as the author of the two stanzas has in effect given to the anti-independence and pro-Serb faction an additional argument against their pro-independence opponents. They can claim that pro-independence faction, in the absence of anything better, have to recruit wartime collaborator and, in their view, a war criminal in support of their cause.

Thus the current anthem stands out from other ex-Yugoslav anthems not only by virtue of several features of the lyrics but in its authorship and societal impact. It is unique in terms of its authorship: no author of other anthems from the region, nor from any other country of Europe, was a political collaborator of the occupiers during World War II. Moreover, no other anthem in this region has deepened so many of the existing identity and political cleavages within the target national group as this one has done within the Montenegrin nation.