Chapter 22. V

View Menu

In Windows: View Menu

As on the Macintosh, you can view the icons in a Windows window in several different ways. Most of the commands you’re used to seeing in the View menu (or the contextual menu for any window) have close relatives in Windows, as follows:

As icons, as list. The Mac OS offers views of the files in a window: Icon, Button, or List. The Windows Large Icons and Small Icons views (available in the View menu) duplicate the Mac’s Icon view, and the Windows Details view matches the Mac’s List view.

Although Windows offers a List view, it has little in common with the Mac’s List view; instead, the Windows List view shows multiple columns of small icons, which frequently requiring horizontal scrolling. See Table 22-1 for a summary of how the different views compare.

As buttons. Windows has no built-in equivalent of the Button View found in Mac OS 8 and later, in which a single click on any enlarged icon “button” opens the corresponding file. Still, if you miss this aspect of the Macintosh interface, you can simulate it on your PC if you have Windows 98 or later:

Open the window in question. Using the View menu, set the view to either Large Icons or Small Icons.

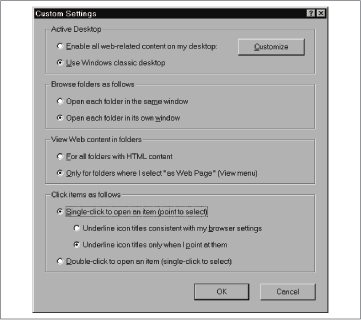

Choose View → Folder Options → Custom → Settings to open the Custom Settings dialog box (see Figure 22-1).

In the bottom set of options, click “Single-click to open an item (point to select).”

Once you’ve done that, icons work much like they do in Button view on the Macintosh, except that you can drag icons to move them. (In the Mac’s Button view, you must drag icons by their names to move them.)

As pop-up window. Windows has no equivalent of the pop-up windows that debuted in Mac OS 8.

Clean Up. When you’re in Icon view on the Macintosh, View → Clean Up makes the icon snap onto an invisible grid in neat alignment. In Windows, the identical command is View → Line Up Icons.

Arrange and sort list. On the Macintosh, you can sort an Icon view or Button view by name, modification date, creation date, size, kind, or label. And through View → View Options → Keep Arranged, you can specify that the sorting is permanent, even when the window shape changes or more icons are added to the window.

Macintosh View | Windows View |

Icon (either large or small, depending on size setting in View → View Options) | Large Icons or Small Icons |

List | Details |

Button | See the preceding instructions |

Small Icon view, with “Keep arranged by name” turned on in View → View Options | List |

Windows is more limited, offering only options to arrange by name, date, type, and size, all of which are accessible from View → Arrange Icons. To keep a Windows window arranged, make sure View → Arrange Icons → Auto Arrange is checked.

While the wording of the Mac’s View menu changes—from Arrange to Sort List—depending on whether the open window is displayed in icon view or list view, Windows makes no similar change—the command is always called Arrange Icons.

Reset Column Positions. In Mac OS 8.5 and later, you can rearrange the columns of a List view by dragging the column titles horizontally. The Reset Column Positions command restores the original configuration of columns.

You can’t rearrange the columns in the Windows 95; although you can in Windows 98, there’s no equivalent in Windows to the Mac’s View → Reset Column Positions command.

View Options. The View Options dialog box for a Macintosh window (View → View Options) lets you set a variety of options for each view. Windows has no equivalents for the options accessible in View Options—except the option to keep icons permanently sorted (View → Arrange Icons → Auto Arrange) and the choice of large or small icons in Icon view (View → Large Icons and View → Small Icons). Windows doesn’t offer options for relative dates, calculating folder sizes, keeping icons aligned with an invisible grid as you move them, multiple icon sizes in Details view, or a choice of which columns display for each window.

Web-browser mimicry. On the other hand, the Windows View menu offers a number of unique options of its own, especially in Windows 98. Many of these commands pertain to Windows 98’s Active Desktop option, in which you view the contents of your hard disk in a web browser-like interface; you’re offered the chance to turn on a variety of toolbars, view individual windows as web pages (icons appear as though they were in a web page), customize each folder’s web page look, and in View → Folder Options, switch all your windows to use the full web-style interface. Most Macintosh users find the hard disk-as-web-browser concept extremely disorienting.

Folder Options. View → Folder Options → View (just Options in Windows 95) lets you customize how files and folders look. (Note, however, that the Folder Options affect all windows, not just the active one.) The most important one is the “Hide file extensions for known file types” checkbox. Although it might seem more Mac-like to hide filename extensions (the three-letter suffixes on all Windows filenames), you may find their absence disconcerting and confusing; for example, you might add a filename suffix to an icon, unaware that one already exists (because Windows is hiding it). You’ll probably find that turning off this “Hide file extensions” checkbox results in a much more comprehensible computing environment.

View → Folder Options → File Types provides an interface to the association of documents to applications. On the Macintosh, you never have to worry about which document was created by which application; but in Windows, you must explicitly tell a GIF image to open in Internet Explorer by giving it a .gif extension. In the File Types tab, you can change that to open in, for example, a graphics program.

On the Macintosh, you might double-click one GIF file that opens into Photoshop, and another that opens into GraphicConverter; thanks to the Mac’s behind-the-scenes creator codes, every document on your Macintosh remembers which program originally created it.

Windows files don’t have creator codes, however. File extensions are absolute in Windows—all .gif files will open in only one program.

In general, installation programs add new file extensions automatically, so you should never need to add a new one. However, you may occasionally wish to modify one that has been “taken over” by the installation of a new program. For example, when you install Netscape Navigator it will try to “take over” the opening of all HTML documents, even if you had previously installed Internet Explorer; similarly, Microsoft’s installer “stole” the file extension .doc from WordPerfect when Windows was first released, forcing all WordPerfect documents to open into Microsoft Word when double-clicked.

Virtual Memory

In Windows: Virtual Memory

For details on virtual memory in Windows, see Memory Usage.

Viruses

In Windows: Viruses

The virus problem is far more serious in the PC world than in the Macintosh world; according to some sources, there are over 40,000 viruses and virus variants written for Windows. Worse, PC viruses tend to be far more malevolent than Macintosh viruses, actively deleting files and damaging hard disks. If you’re using a PC, you must have an anti-virus program, and you must keep it up to date with new virus definitions.

Symantec and Network Associates dominate the PC antivirus market. Both offer a number of products, including Symantec’s Norton AntiVirus and VirusScan from Network Associates. You can find more information about Norton AntiVirus and about viruses in general at http://www.symantec.com/avcenter/. For information about the various Network Associates anti-virus products, visit http://www.nai.com/products/antivirus/.

Word macro viruses, macros written in WordBasic that propagate by infecting Word documents, are another increasing threat today. Word files are ubiquitous in the business world, and some macros run when the document is opened; as a result, these viruses can spread quickly. (They affect both PC and Macintosh users of Microsoft Word.) Fortunately, most anti-virus programs can help find and eliminate Word macro viruses. Furthermore, whenever you open a document containing Word macro files, Word 97 or later offers to disable macros in documents when you’re opening them—a convenient solution that rules out any possibility that the document you’re about to open will infect your system.