Chapter 29. E

Edit Menu

On the Macintosh: Edit Menu

The Edit menu in most Macintosh programs is almost identical to the one in almost every Windows program. Most of the menu items—Cut, Copy, Paste, and so on—have the same names and keyboard shortcuts as in Windows, except that you use the Command key instead of the Ctrl key.

The commands in the Macintosh Edit menu work exactly as they do in Windows—you can cut, copy, or paste highlighted material in your applications. On the Macintosh, however, you can’t use the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands on Desktop icons themselves, to move for copy actual files to other windows.

For information on the main commands in the Edit menu, Cut, Copy, Paste, and Undo, see their respective entries. Among the other Edit menu items are:

Paste Shortcut. Since the Mac’s Paste command can’t paste a file, there’s no Paste Shortcut command.

Select All. The Select All command (Ctrl-A) in Windows is identical to the Mac’s Select All command (Command-A)—with one exception. In Windows, Select All highlights all the icons in a window. But if you’re editing a file’s name, Select All doesn’t select all the text in the name; the Ctrl-A keyboard shortcut doesn’t work at all. On the Macintosh, Select All highlights text if you’re editing a filename, and highlights all icons in the window if you’re not.

Invert Selection. The Invert Selection command, which highlights all the files in a window that aren’t already selected, has no equivalent on the Macintosh.

EISA Slots and Cards

On the Macintosh: PCI Slots and Cards

See PCI Slots and Cards.

Ejecting Disks

On the Macintosh: Ejecting Disks

On a PC, most people eject disks by pushing the manual-eject button on the front panel of every floppy, Zip, CD, and other drive. On the Macintosh, the manual-eject button doesn’t work at all when a disk is in the machine. Instead, you eject a disk using a menu command or by dragging a disk icon to the trash. You can eject a Macintosh disk in any of these ways:

Highlight the disk, and then choose Special → Eject (Command-E).

Highlight the disk, and then choose File → Put Away (Command-Y).

Drag the disk’s icon to the Trash. In Windows, this would erase all the files on the disk, but on the Macintosh, doing so ejects the disk.

Choose Special → Restart or Special → Shut Down to restart or shut down the Macintosh, which ejects the disk in the process. (There are some exceptions: CD-ROMs generally remain in the machine when you shut down or restart, and so do Zip or Jaz disks you’ve configured, using the Iomega software, to remain in their drives.)

If a floppy disk is in the drive before you turn the Macintosh on, you can eject it on startup by holding down the mouse button. If the disk doesn’t have a System Folder on it, though, even that action isn’t necessary, because the Macintosh ejects the disk automatically once it realizes it can’t boot from the disk.

Note

When the standard software methods of ejecting a Macintosh disk don’t work—when the disk is jammed, for example—you can eject it manually. Insert a straightened paperclip into the small hole next to the floppy slot, CD-ROM, or Zip drive slot. Push straight in to activate the manual eject button.

Email attachments

On the Macintosh: Email Attachments

One of the best ways to transfer files from a PC to a Macintosh is by attaching the files to an email message. Unfortunately, although this technique can work extremely well, it’s fraught with problems. For more information on how to transfer files successfully, see the “Email” section of Transferring Files to the Macintosh.

Emulators

On the Macintosh: Emulators

This book assumes that you have access to a physical PC or a physical Macintosh. However, several third-party programs let you run Windows—and Windows software—on the Macintosh; there are even programs that let you run Macintosh programs, in a limited way, on a PC.

Running Windows on the Macintosh.

Virtual PC (Connectix)

Virtual PC has an excellent reputation. One advantage of Virtual PC over Soft-Windows (described next) is that it emulates an entire PC, not just Windows. Thus, you can use Virtual PC to run PC-compatible operating systems other than Windows, such as Windows NT or even OS/2. You can learn more about Virtual PC at http://www.connectix.com/html/connectix_virtualpc.html.

SoftWindows (Insignia Solutions)

SoftWindows (and its predecessor, SoftPC) have been around for many years. Its price and feature list are very similar to Virtual PC’s; one pleasant feature is TurboStart, which memorizes the state of your emulated Windows environment when you quit the program (Virtual PC has a similar feature). The next time you resume SoftWindows, it starts up in a fraction of the time an actual PC would take to start up. You can find more information on SoftWindows and other Insignia products at http://www.insignia.com/.

Whether emulation software makes sense for you depends on your proposed uses. Emulation works well if you need to run Windows programs only occasionally; you’re more likely to encounter flakiness if you use the system heavily.

If you want to run Windows software on a Macintosh, but don’t want to put up with the slow speeds of emulation software, many Macintosh fans look into an Orange Micro OrangePC. This PCI card includes a Pentium processor and the other circuitry found in a real PC, and can therefore run software at about the same speeds. You save considerable desk space and (if you have a fancy monitor, keyboard, and ergonomic setup) equipment cost.

On the other hand, compare prices—it may actually be less expensive to buy a PC. Furthermore, you may occasionally experience glitches when trying to move data back and forth between the two operating systems.

You can find more information about Orange Micro’s products at http://www.orangemicro.com/.

Running Macintosh software on a PC. Software that lets you run Macintosh software on a PC is a much more difficult proposition, and attempts to write such a program have had decidedly mixed results. Such programs can’t run many Macintosh programs because their creators can’t legally copy necessary code from the Macintosh ROM chips. The most successful Macintosh emulator, called Executor, comes from a company called ARDI. You can learn more information about Executor (and find the compatibility list of software it can run) at http://www.ardi.com/.

End Task

On the Macintosh: Force Quit

If a program is behaving oddly in Windows and refusing to quit, you can press Ctrl-Alt-Delete to bring up the Close Program dialog box. From there, you can force the offending program to quit, although unsaved changes are lost in the process.

The Macintosh has a similar feature. If an application seems frozen, press Command-Option-Esc to bring up a dialog box asking if you would like to force the current application to quit. Make sure you’re forcing the proper application to quit; due to the way the Macintosh multitasks, another application may in fact be “current” even though it’s not frontmost. If the program named in the dialog box isn’t the one you think is frozen, click Cancel, wait a few seconds, and press Command-Option-Esc again. Clicking the Force Quit button often jettisons the offending program, which gives you the opportunity to save your changes in any other running programs and then restart the computer to restore stability.

Unfortunately, exactly as in Windows, this emergency procedure doesn’t always work. It sometimes results in a more severely frozen system; at this point, you have no choice but to restart the Macintosh.

Enter Key

On the Macintosh: Enter Key, Return Key

PC keyboards have a pair of Enter keys: one in the main typing area and one on the numeric keypad. The two are functionally identical.

On the Macintosh, however, the key in the main typing area is labeled Return, not Enter. Most of the time, Return and Enter have the same function, but in some programs, the two have different functions. In Excel, for example, pressing the Return key moves the input cell downward in a block of highlighted cells, and the Enter key moves across. Similarly, if you’re using a macro program, you can assign macros independently to each key.

Esc Key

On the Macintosh: Esc Key

In Windows, the Esc (short for Escape) key has numerous functions. On the Macintosh, however, Esc has little purpose beyond its ability to cancel a dialog box or close an open menu. Macintosh users use the Command-period keystroke far more often, which performs the same functions and more, including canceling a lengthy procedure (such as downloading or copying files) in progress. (In the rare Macintosh program where Esc fails to close the dialog box, Command-period usually does the trick.)

The Esc key is also used on the Macintosh to force quit a frozen program—press Command-Option-Esc and then click the Force Quit button in the dialog box that appears. For more information, see End Task.

Ethernet

On the Macintosh: Ethernet

Ethernet is a networking protocol that’s supported equally well by the Macintosh and Windows, so it’s an excellent method of connecting a Macintosh and a PC to transfer files or share other network resources. For more information about moving files back and forth, see Transferring Files to the Macintosh.

Eudora

On the Macintosh: Eudora

Qualcomm’s Eudora is one of the most popular Internet email programs for Windows, although it started life as a Macintosh program. It remains popular on the Macintosh, and the two versions are extremely similar, often down to the keyboard shortcuts. If you’re used to Eudora Light or Eudora Pro in Windows, you should try it on the Macintosh, because it’s easy to switch.

The other advantage of using Eudora in both Windows and the Macintosh is that you’ll experience the fewest problems when sending attachments back and forth.

For more information, or to download a free copy of Eudora Light, visit http://www.eudora.com/. Also check out Eudora 4.2 for Windows & Macintosh: Visual QuickStart Guide (http://www.tidbits.com/eudora/).

Exiting Programs

On the Macintosh: Quitting Programs

There are two differences between quitting programs in Windows and in the Macintosh OS. First, the wording is different—on the Macintosh, you choose Quit, not Exit, from the File menu. Second, when you close the last window in a Macintosh program, the program remains running, whereas in Windows, it generally quits.

Explorer

On the Macintosh: Finder

Technically, the Windows Explorer is the program that creates and maintains the Desktop and many of the other visible aspects of Windows. However, you can also run the Explorer as a standalone application, at which point it displays a two-pane interface for navigating the hierarchy of your hard disk.

On the Macintosh side of things, the equivalent program is the Finder, which gives you the Macintosh Desktop, icons, and windows. However, the Finder doesn’t offer a two-pane display like the Explorer; there’s no way to have a window that lets you navigate the folder hierarchy in one pane and displays folder contents in the other.

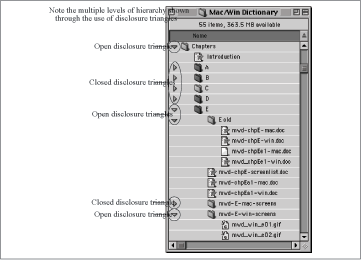

That said, in List view (choose View → as List), the Finder offers “disclosure triangles” next to each folder. Click a triangle to view, outline-like, the contents of that folder (see Figure 29-1). This feature lets you move around the hierarchy of your hard disk in much the same way you can in the two-pane Explorer view in Windows.

Caveats and tricks. Keep a few things in mind when working with the Finder’s folder triangles:

You can view the contents of a folder either by clicking the disclosure triangle or by opening the folder into a window, but not both. If you click the triangle of an open folder, the folder’s window closes; if you double-click a folder whose disclosure triangle is open (down), the triangle closes (points right), and the folder’s contents appear in a new window.

Because the contents of a folder are indented under the folder’s name when you click the disclosure triangle, you may need to make windows wider to see the contents.

You can Option-click a folder’s triangle to expand the folder and all folders inside it, in effect clicking all the folder triangles, no matter how many folders deep. Option-click the triangle again to collapse the folder and all subfolders.

You can also open (to one level) all folder triangles in a single window: choose Edit → Select All, and then press Command-right arrow. Press Command-left arrow to close them all again.