The Navy’s organization is large, unique, and complicated, making it a challenge to understand. And because the Navy works so closely with the other services, it is not enough to merely understand how the Navy is organized; you must also have some idea of how it fits into the Department of Defense. This chapter will unravel some of the complexity and give you a better understanding of how the Navy is able to carry out its many assigned tasks.

AN ORGANIZATION WITH MANY DIFFERENT PARTS

One might think that setting up a navy organization would be a relatively simple thing; that ships would be organized into fleets to operate in certain waters of the world and that admirals would command those fleets; that a chain of command could be simply drawn from the commanding officers of ships to the commanders of fleets and ultimately to the senior-most admiral in charge of the whole navy. But this simplistic vision ignores the reality that there are actually a number of chains of command that must be understood if you are going to understand how the U.S. Navy is organized.

To begin with, the Navy consists of more than ships. There are also aircraft and submarines, SEALs, Seabees, Marines, and more that make up what we can collectively describe as the operating forces of the Navy. Sometimes you will hear the operating forces referred to as simply “The Fleet.”

Further, these operating forces cannot function independently. There must be a supply system to ensure that the operating forces have fuel, ammunition, and the like. Some means of repairing the ships, aircraft, and other parts of the fleet must be in place, and medical facilities must be available to care for battle casualties and the sick. These and other considerations mean that there must be facilities ashore to support those ships and aircraft. These facilities are often referred to collectively as “The Shore Establishment.”

And, as mentioned above, another complication stems from the realization that navies rarely operate alone, that modern warfare and readiness for war require all of the armed forces to operate together—or jointly—in various ways.

To add another complication, we sometimes operate with the armed forces of other nations. Although similar to “joint operations” with our own forces, we use the term “combined operations” to refer to operations involving other nations’ forces.

And one more complicating factor comes from the fact that our nation is a democracy, and one of our governing principles is civilian control of the military, which means that there will be civilians in your chain of command, such as the President of the United States (who is commander in chief of the armed forces) and the Secretary of the Navy.

Some Things to Keep in Mind

In the military, the term “chain of command” is roughly synonymous with “organization.” The former is a path of actual legal authority, while the latter is a little less formal, but for most purposes the two terms can be considered the same.

The factors mentioned above—the operating forces needing support from ashore, the need for joint operations among the services or combined operations among nations, and the necessity for civilian control of the armed forces—all combine to make for a more complicated organization than we might wish for, but understanding that organization can be helped by keeping certain things in mind.

TWO CHAINS OF COMMAND

To begin with, your unit (ship, squadron, etc.) is likely to be part of two separate (but sometimes overlapping) chains of command at the same time: an administrative chain of command and an operational chain of command.

![[8.1] Modern warfare often...](../images/f0167-01.jpg)

![[8.2] A U.S...](../images/f0167-02.jpg)

The administrative chain of command is what keeps the Navy functioning on a day-to-day basis so that the ships, aircraft, and other elements of the fleet are able to carry out operational tasks when assigned. This is the chain of command that takes care of the less colorful but essential elements of preparedness, such as training, repair, supply, personnel assignment, intelligence support, communications facilities, weather prediction, and medical treatment.

The operational chain of command controls forces (ships, aircraft, etc.) that are assigned to combat operations, operational readiness exercises, humanitarian relief missions, evacuations, etc., or are on station carrying out missions like sea control and deterrence.

The operating forces are more or less permanently organized in an administrative chain of command, while they are frequently reassigned to different operational chains of command as needs arise. For example, your ship or squadron may be involved in a scheduled fleet exercise (with its own specific operational chain of command) and suddenly be ordered to conduct a search-and-rescue operation in the aftermath of a typhoon, which will require a whole different chain of command.

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY VS. NAVY DEPARTMENT

To clarify one more possible area of confusion, United States Navy Regulations (NAVREGS) actually defines three principal elements within the Department of the Navy. Besides the operating forces and the shore establishment, NAVREGS also specifies “the Navy Department,” which it defines as consisting of “the central executive offices of the Department of the Navy located at the seat of government . . . comprised of the Office of the Secretary of the Navy, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, and Headquarters, Marine Corps.” This means that the terms “Department of the Navy” and “Navy Department” are defined as two different things: the former refers to the entire Navy organization—all operating forces (including the Marine Corps), the entire shore establishment, and all reserve forces—and the latter refers to the executive offices, most of which are located in Washington, D.C. As indicated early in this chapter, complicated!

DON AND DOD

The Department of the Navy (DON) is an integral part of the Department of Defense (DOD), which also includes the Army and the Air Force, and DON and DOD are intertwined to a significant degree.

There is a civilian head of the Navy, known as the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV), and a military head, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). The CNO is subordinate to SECNAV.

The U.S. Marine Corps is part of the Department of the Navy, but is in many ways a separate service, having its own senior military commander (the Commandant of the Marine Corps) who serves on the Joint Chiefs of Staff but answers to the same civilian official (the Secretary of the Navy).

“TWO HATS”

Some individuals in this organizational structure may “wear two hats,” an expression that means one person can actually have more than one job, and often those two (or more) jobs might be in different parts of the organizations described above. For example, the commander of the Navy’s Fifth Fleet might also hold the position of “Commander of U.S. Naval Forces, Central Command” (a joint command position within the Department of Defense chain of command).

The Chief of Naval Operations “wears a number of hats” in that he or she is responsible for ensuring the readiness of the Navy’s operating forces but is also the head of the shore establishment. And while this admiral is the senior military officer in the Navy, he or she also works directly for the civilian Secretary of the Navy and serves as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in matters that involve working with the other armed services.

ALLIED CHAINS OF COMMAND

There are also allied chains of command that sometimes must be considered. For example, because the United States is a key member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a U.S. Navy admiral can be the NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe and be responsible for forces belonging to member nations as well as those of the United States.

HELPFUL HINTS

When dealing with the Navy’s organization, keep in mind that you probably will not need to know every detail of that organization. The information provided is for an encompassing overview. Try to grasp the essentials—particularly those that apply directly to your job—but do not worry if you cannot remember exactly how it all fits together. Few people can.

Something else to keep in mind is that this organization frequently changes. Commands are renamed, offices shift responsibilities. Some confusion may be avoided if you do not assume that what you remember will always be the same. Also be wary of the Internet; while it is a wonderful information tool, it must be used with caution. Websites are not always kept up to date, and older (out-of-date) items sometimes show up when using a general search engine.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

As discussed above, the Department of the Navy (DON) is part of the Department of Defense (DOD), and some of the Navy’s organization is directly intertwined with the DOD joint command structure. In its simplest breakdown, there are four principal components to DOD:

![]() The Secretary of Defense and his or her supporting staff in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF/OSD)

The Secretary of Defense and his or her supporting staff in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF/OSD)

![]() The Joint Chiefs of Staff and their supporting staff (JCS)

The Joint Chiefs of Staff and their supporting staff (JCS)

![]() The individual military departments (services): Army, Air Force, and Navy

The individual military departments (services): Army, Air Force, and Navy

![]() The Unified Combatant Commands (COCOMs)

The Unified Combatant Commands (COCOMs)

Most people who watch even a little news are aware that there is a Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) heading up DOD and that he or she is assisted by a senior military officer known as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS), who can come from any of the services and whose principal duties include advising the President, the National Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense. Those people who are more informed may also know that the senior military officers of each service (the Chief of Naval Operations; the Commandant of the Marine Corps; the Chief of Staff of the Army; and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force) serve collectively as the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) under the Chairman and the Vice Chairman. Probably less known is that there is another member of the JCS: the Chief of the National Guard Bureau.

Note that while the Marine Corps is a service within the Department of the Navy, the Commandant is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The Coast Guard is another unique entity. It is, by law, the fifth military branch of the U.S. armed services, but it is assigned to the Department of Homeland Security, rather than DOD. And while the Coast Guard frequently operates in support of the Navy and DOD when it is called upon to perform national defense missions, the Commandant of the Coast Guard is not a formal member of the Joint Chiefs. During wartime or national emergency, the President can have the Coast Guard assigned to the Department of the Navy, but the last time this transfer occurred was just before and during World War II, and it is unlikely that it will ever happen again.

Both the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff have fairly large organizations working for them. Supporting SECDEF is a staff structure known collectively as the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), which includes a deputy secretary of defense, a number of under secretaries, assistant secretaries, and other officials in charge of specific aspects of running DOD.

Likewise, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) also has a support organization called “the Joint Staff.”

For operational matters—such as contingency planning, responding to an international crisis, going to war, or participating in a major joint operational exercise—the chain of command is a bit different. This operational chain of command is sometimes referred to as the “U.S. National Defense Command Structure” and begins with the President of the United States in his constitutional role as commander in chief of the Armed Forces. It then goes through the Secretary of Defense (with the Chairman of the JCS and the service chiefs serving as principal advisers) to those generals and admirals known as “unified combatant commanders” (explained below).

![[8.3] U.S. National...](../images/f0171-01.jpg)

[8.3] U.S. National Defense Command Structure

It is important that you understand the role of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the operational chain of command. The Chairman (with the assistance of the other Joint Chiefs) technically serves only as a principal adviser to the Secretary of Defense, but at SECDEF’s direction he or she often issues directives to the unified combatant commanders, which can create the illusion that CJCS is in the chain of command between SECDEF and the unified commanders; however, these directives are always issued with the understanding that they originate with SECDEF, not CJCS.

Unified Combatant Commands

As described above there are a number of “Unified Combatant Commanders” who answer directly to the Secretary of Defense. These generals and admirals from the various services are sometimes referred to as just “unified commanders” or “combatant commanders” or “CCDRs.” You may also see the abbreviation “COCOM” sometimes used, but CCDR is the correct abbreviation when referring to the commanders of these combatant commands.

Each CCDR is responsible for a specific geographic region of the world (sometimes referred to as an Area of Responsibility or AOR, such as Africa or Europe) or has a worldwide functional area of responsibility (such as all special operations or military transportation). It is through these CCDRs that the DOD and Navy operational organizations come together.

Currently, six of the nine CCDRs are responsible for specific geographic regions of the world:

Africa Command (AFRICOM) covers all of Africa except Egypt, with headquarters at Kelley Barracks in Stuttgart, Germany.

Central Command (CENTCOM) includes countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia (most notably Afghanistan), with headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida.

European Command (EUCOM) covers more than fifty countries and territories, including Europe, Russia, Greenland, and Israel. Its headquarters is in Stuttgart, Germany. The commander of EUCOM simultaneously serves as the Supreme Allied Commander, Europe within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with its headquarters at Mons, Belgium.

Northern Command (NORTHCOM) is tasked with providing military support for civil authorities in the United States and protecting the territory and national interests of the United States including Alaska (but not Hawaii), Puerto Rico, Canada, Mexico, and the air, land, and sea approaches to these areas. NORTHCOM would be the primary defender against a mainland invasion of the United States. Its headquarters is at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado.

Pacific Command (PACOM) is responsible for the gigantic Pacific Ocean area, to include parts of the Indian Ocean, and has its headquarters in Camp H. M. Smith, Hawaii.

Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) provides contingency planning and operations in Central and South America, the Caribbean, and the Panama Canal. SOUTHCOM’s headquarters is in Doral, Florida.

The other three COCOMs have worldwide responsibilities that are functionally, rather than geographically, oriented.

Special Operations Command (SOCOM) oversees the various Special Operations Component Commands of the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps and is headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base.

Strategic Command (STRATCOM) is charged with space operations (such as military satellites), information operations (such as information warfare), missile defense, global command and control, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, global strike and strategic deterrence (the United States nuclear arsenal), and combating weapons of mass destruction. STRATCOM is headquartered at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha, Nebraska.

Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) provides air, land, and sea transportation for the Department of Defense, both in times of peace and times of war, and is headquartered at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois.

Each of these commands is more formally addressed with “United States” preceding (as in “United States Africa Command”) and is sometimes abbreviated similarly (as in “USAFRICOM”).

Remember that the CCDRs answer directly to the commander in chief (the President of the United States) through the Secretary of Defense, with the JCS serving as advisers and the CJCS sometimes passing orders from the President/SECDEF on to the CCDRs.

![[8.4] Geographic Areas of...](../images/f0174-01.jpg)

[8.4] Geographic Areas of Responsibility for Unified Commands

Service Component Commanders

Working directly for the CCDRs are the service component commanders. These are commanders who control personnel, aircraft, ships, and other elements—from their individual services—that can be made available to the unified commander for operations when needed. For example, the joint CENTCOM commander has the following service component commands assigned to carry out those operations that fall within CENTCOM’s area of responsibility:

United States Army Central Command (ARCENT)

United States Central Command Air Forces (CENTAF)

United States Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT)

United States Marine Forces Central Command (MARCENT)

Sub-unified Commands

Some combatant commands have sub-unified commands assigned that are joint in nature, rather than service specific. For example, U.S. Cyber Command at Fort Meade is part of STRATCOM, but because it has personnel from the different services assigned, it is designated a “sub-unified command” rather than a service component command.

THE NAVY

As described above, the Navy is organized in two different (but related) ways at the same time: the operational chain of command and the administrative chain of command. Depending upon where you are assigned, you may be part of one or both of these organizations.

Both of these chains of command have the President of the United States at the top as commander in chief. Below the President is the Secretary of Defense, with the Chairman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff as his or her principal advisers. Below SECDEF, the chains are different. For operational matters, the SECDEF issues tasking orders directly to the unified combatant commanders (CCDRs), and for administrative matters, SECDEF relies upon the Secretary of the Navy to keep the Navy (and Marine Corps) manned, trained, and ready to carry out assigned missions.

The Operational Chain of Command

In centuries past, naval warfare could be effectively waged more or less independently, but in the modern age the importance of joint warfare cannot be overemphasized. In the vast majority of modern operations, whether they are combat, humanitarian, readiness, deterrent, or specialized, several or all of the U.S. armed forces must cooperate, coordinate, and combine their forces and plans to maximize their effectiveness and ensure mission accomplishment.

The Navy’s operational chain of command is headed by the appropriate unified combatant commanders (CCDRs) described above. As previously mentioned, the officers commanding these combatant commands may be from any of the armed services (except the Coast Guard). The chain becomes purely naval below the CCDR with “naval component commanders” exercising operational control over one or more of the “numbered fleet commanders.”

NAVAL COMPONENT COMMANDERS

CCDRs have component commanders assigned to them. Once a unified combatant commander has determined what assets (such as troops, ships, and aircraft) he or she will need to carry out a specific mission, that commander will rely upon the component commanders to provide those forces and coordinate their actions.

As already stated, this is the first level of command in the joint forces structure that is purely naval. There are a number of these naval component commands to meet the needs of the various unified combatant commands.

United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT or simply PACFLT). This naval component commander primarily serves the naval needs of the PACOM unified commander, and the primary AOR is the same as that of PACOM (Pacific and Indian Oceans), but PACFLT also provides assets to CENTCOM, SOUTHCOM, EUCOM, AFRICOM, and STRATCOM when required. PACFLT is headquartered at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and exercises control of both the Third and Seventh Fleets.

United States Naval Forces Europe (USNAVEUR or simply NAVEUR). From headquarters in Naples, Italy, COMUSNAVEUR plans, conducts, and supports naval operations in the European AOR during peacetime, crises, or war, answering directly to the EUCOM unified commander. He or she is supported by the Commander of the Sixth Fleet and by the Commander, Navy Region Europe (both are also headquartered in Naples, Italy).

United States Naval Forces Central Command (USNAVCENT or simply NAVCENT). Serving as naval component commander for the U.S. Central Command, NAVCENT, headquartered in Bahrain, is responsible for naval activities in the Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf, Red Sea, and part of the Indian Ocean. The vice admiral in command of this component also wears a second hat as Commander of the Fifth Fleet.

United States Fleet Forces Command (USFLTFORCOM or simply FLTFORCOM). Headquartered in Norfolk, Virginia, FLTFORCOM supports both STRATCOM and NORTHCOM as well as providing some naval support to EUCOM and CENTCOM. This component commander also serves as primary advocate for fleet personnel, training, maintenance, and operational issues, reporting administratively to the CNO.

United States Naval Forces Southern Command (USNAVSO or simply NAVSO). Headquartered at Naval Station Mayport, Florida, NAVSO’s areas of operation are in South America, Central America, the Caribbean, and surrounding waters.

United States Naval Special Warfare Command (NAVSPECWARCOM or simply NAVSOC). Headquartered at the Naval Amphibious Base Coronado in San Diego, California, this is the naval component of the United States Special Operations Command.

United States Fleet Cyber Command/U.S. Tenth Fleet (FCC-C10F). Headquartered at Fort Meade, Maryland, this naval component command is an operational component of the U.S. Navy Information Dominance Corps and serves as the central operational authority for networks, cryptologic/signals intelligence, information operations, electronic warfare, and space capabilities in support of forces afloat and ashore.

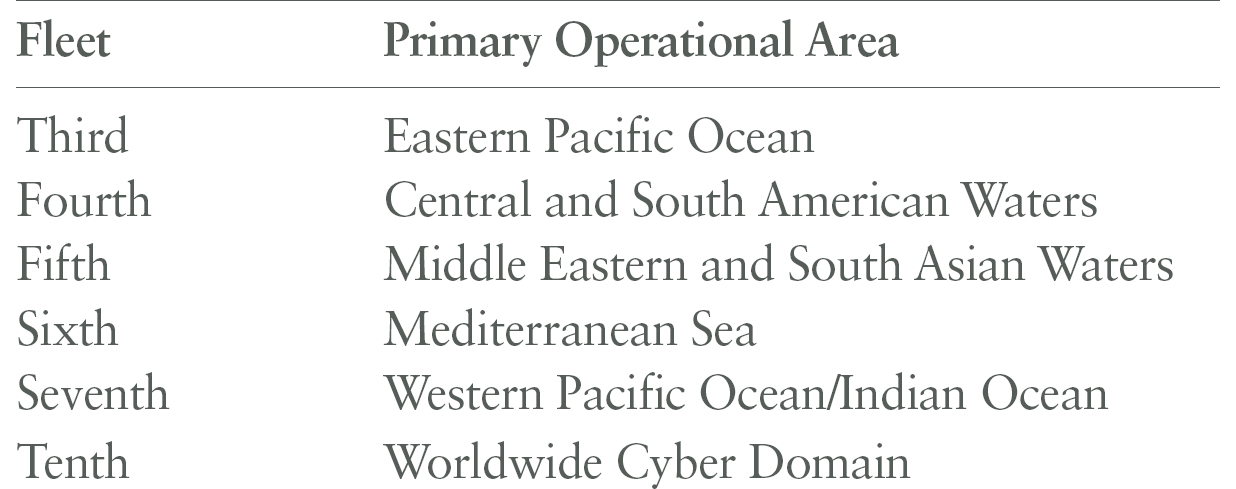

NUMBERED FLEET COMMANDERS

Commanding the ships, submarines, and aircraft that operate in direct support of the naval component commanders are vice admirals in charge of the numbered fleets. Like the component commanders, these commanders have support staffs and facilities ashore, but the numbered fleet commanders also have a flagship from which to conduct operations at sea as missions require. Individual ships, submarines, and aircraft squadrons are assigned to different fleets at different times during their operational schedules. For example, a destroyer assigned to Third Fleet while operating out of its homeport of Pearl Harbor might later deploy to the Seventh Fleet in the western Pacific for several months. There are currently six numbered fleets in the U.S. Navy.

The apparent gaps (no First Fleet or Second Fleet, for example) is because of historical evolution rather than oversight. Numbered fleets come and go according to the current needs. For example, in World War II there were Eighth, Tenth, and Twelfth fleets to meet specific needs of that global conflict that were later deactivated.

Third Fleet. With shore headquarters in San Diego, California, Third Fleet operates primarily in the Eastern Pacific and supplies units on a rotational basis to Seventh Fleet in the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans and to Fifth Fleet in the Middle East.

Fourth Fleet. With shore headquarters in Mayport, Florida, Fourth Fleet has operational control of those units operating in the SOUTHCOM AOR.

Fifth Fleet. With shore headquarters in Bahrain on the Persian Gulf, Fifth Fleet has operational control of those units operating in the CENTCOM AOR.

Sixth Fleet. Operating in the Mediterranean Sea with shore headquarters in Gaeta, Italy, Sixth Fleet has both U.S. and NATO responsibilities (the latter as components of the NATO Strike and Support Forces, Southern Europe).

Seventh Fleet. With shore headquarters in Yokosuka, Japan, Seventh Fleet is responsible for the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans. The majority of units come from Third Fleet on a rotational basis, but there are some permanently assigned assets in the Seventh Fleet that are homeported in Japan.

Tenth Fleet. Headquartered at Fort Meade, Maryland, the Tenth Fleet operates worldwide in cyber space. It works with the Fleet Cyber Command to achieve the integration and innovation necessary for warfighting superiority across the full spectrum of military operations in the maritime, cyberspace, and information domains.

TASK ORGANIZATION

An entire fleet is too large to be used for most specific operations, but a particular task may require more than one ship. To better organize ships or other units into useful groups, the Navy developed an organizational system that has been in use since World War II. Using this system, a fleet can be divided into task forces, and they can be further subdivided into task groups. If these task groups still need to be further divided, task units can be created, and they can be further subdivided into task elements.

![[8.5] The Tenth Fleet...](../images/f0179-01.jpg)

A numbering system is used to make it clear what each of these divisions is. The Seventh Fleet, for example, might be divided into two task forces numbered TF 71 and TF 72. If TF 72 needed to be divided into three separate divisions, they would be task groups numbered TG 72.1, TG 72.2, and TG 72.3. If TG 72.3 needed to be subdivided, it could be broken into task units numbered TU 72.3.1 and TU 72.3.2 (this “decimal” system might not sit well with your high school math teacher, but it works for the Navy). Further divisions of TU 72.3.1 would be elements numbered TE 72.3.1.1 and TE 72.3.1.2. This system can be used to create virtually any number of task forces, groups, units, and elements, limited only by the number of ships available.

Using the operational chain of command shown in Figure 8.6 we can imagine an example of how this system might work from one ship up through a CCDR.

Keep in mind that this shows only one path up the chain—there would also be other ships assigned to the various task elements and units, and there might be other task components (such as a Task Element 76.1.1.2 and Task Groups 76.2 and 76.3, etc.).

In this example, dock landing ship USS Fort McHenry (LSD 43) has been tasked with delivering Marines to one of several key locations in the Pacific as part of a larger operation that is responding to a crisis. Task Force 76 shown in the figure is responsible for carrying out amphibious operations in the Pacific operating area, and the commander (CTF 76) has divided her task force into two task groups, one to cover the eastern part of her area of responsibility (TG 76.1) and the other (TG 76.2) to cover the western part. CTG 76.1 has further divided his assigned forces into two task units (TU 76.1.1 and TU 76.1.2), the first tasked with transporting Marines to a troubled area and the other made up of destroyers to protect the transport unit. There are two LSDs assigned to TU 76.1.1, and the task unit commander has designated each of them as task elements, with each given a specific landing beach. The commanding officer of USS Fort McHenry has been designated CTE 76.1.1.1 to coordinate landing the Marines in her ship onto the northern beach, and the CO of the other LSD will do the same for the southern beach.

The Administrative Chain of Command

As mentioned above, there is a chain of command within the Navy that is parallel to the operational chain; this one involves many (but not all) of the same people who “wear more than one hat” in order to carry out functions within each chain. The administrative chain is concerned with readiness more than execution, focusing on such vital matters as manning, training, and supply, so that the operating forces are prepared to carry out those missions assigned by the operational chain of command.

SECRETARY OF THE NAVY (SECNAV)

SECNAV has an Under Secretary of the Navy as his or her direct assistant, and as can be seen in Figure 8.7, there are several Assistant Secretaries of the Navy (ASN) to handle specific administrative areas of the Navy.

![[8.6] An example of...](../images/f0181-01.jpg)

[8.6] An example of part of a task organization

![[8.7] The Secretary of...](../images/f0181-02.jpg)

[8.7] The Secretary of the Navy and his or her assistants

In addition to these civilian assistants, SECNAV also has a number of military assistants, such as the Navy’s Judge Advocate General, the Naval Inspector General, and the Chief of Information. Other military officers answer directly to SECNAV’s civilian assistants, such as the Chief of Naval Research who reports to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition, and the Auditor General who reports to the Under Secretary of the Navy.

CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS

Reporting directly to the Secretary of the Navy is the Chief of Naval Operations. The CNO is the senior military officer in the Navy and as such, he or she is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (discussed above) and is also the principal adviser to the President and to the Secretary of Defense for naval matters. The CNO is always a four-star admiral and is responsible to the Secretary of the Navy for the manning, training, maintaining, and equipping of the Navy, as well as its operating efficiency. Despite the title “CNO,” he or she is not in the operational chain of command.

Besides a Vice Chief of Naval Operations (VCNO), the CNO has a number of admirals working for him or her who oversee specific functions within the Navy, as indicated in Figure 8.8. Most of them are identified by the title “Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (DCNO),” the exception being the “Director of Naval Intelligence.”

OPNAV Staff. Collectively, the CNO’s staff is commonly referred to as “the Navy Staff” or “OPNAV” (derived from “operations of the Navy” but is better thought of as simply the “Office of the Chief of Naval Operations”). OPNAV also assists SECNAV, the under secretary, and the assistant secretaries of the Navy.

These admirals have staffs and subordinate commanders working for them, with many of these officers identified by subordinate “N-codes” as well. For example, the vice admiral who is assigned as DCNO for Integration of Capabilities and Resources has a number of rear admirals working for him or her as N85 (Expeditionary Warfare), N86 (Surface Warfare), N87 (Submarine Warfare), N88 (Air Warfare), and so on.

There are numerous other assistants to the CNO on the OPNAV staff, such as the Chief of Legislative Affairs (N09L), the Director of Naval Education and Training (N00T), the Surgeon General of the Navy (N093), who oversees all medical activities within the Department of the Navy, the Chief of Chaplains (N097), and the Director of Navy Reserve (N095).

![[8.8] Office...](../images/f0183-01.jpg)

[8.8] Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV)

The Director, Navy Staff directs OPNAV staff principal officials in support of CNO executive decision-making, delivers management support to the OPNAV staff, and serves as sponsor for thirty of the Navy’s most important naval commands.

Shore Establishment. In addition to the OPNAV staff, there are a number of shore commands directly under the CNO that support the fleet, including the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Naval Security Group Command, the Naval Safety Center, the Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command, the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center, the Naval Legal Service Command, the Bureau of Naval Personnel, the Naval Education and Training Command, and the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. A number of these commands are dual-hatted: for example, the head of the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS), known officially as the “Chief of Naval Personnel,” is also the Deputy CNO for Manpower and Personnel (N1), and the Commander, Naval Education and Training Command serves as a member of the OPNAV staff, advising the CNO as the Director of Naval Education and Training (N00T).

Systems Commands. There are also five systems commands that oversee many of the technical requirements of the Navy and report to the CNO and SECNAV.

Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) is the largest and serves as the central activity for the building of ships, their maintenance and repair, and the procurement of those systems and equipment necessary to keep them operational. Among its many functions and responsibilities, NAVSEA also oversees explosive ordnance safety as well as salvage and diving operations within the Navy.

Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) researches, acquires, develops, and supports technical systems and components for the aviation requirements of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard.

Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR) is responsible for the Navy’s command, control, communications, computer, intelligence, and surveillance systems. These systems are used in combat operations, weather and oceanographic forecasting, navigation, and space operations.

![[8.9] Major Components of...](../images/f0185-01.jpg)

[8.9] Major Components of the Navy Shore Establishment

Naval Supply Systems Command (NAVSUP) provides logistic support to the Navy, ensuring that adequate supplies, such as ammunition, fuel, food, and repair parts, are acquired and distributed worldwide to naval forces.

Naval Facilities Engineering Command (NAVFAC) is responsible for the planning, design, and construction of public works, family and bachelor housing, and public utilities for the Navy around the world. NAVFAC manages the Navy’s real estate and oversees environmental projects while keeping its bases running efficiently.

Type Commands. For administrative purposes, such as personnel manning, training, and scheduled repairs, the Pacific and Atlantic fleets have ships and aircraft classified and organized into commands related directly to their type. These groupings are called “type commands,” and there are six.

Naval Surface Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (SURFLANT) administers to the needs and ensures the readiness of all surface ships (cruisers and destroyers, as well as amphibious, service, and mine warfare ships) assigned to the Commander of the U.S Fleet Forces Command (COMFLTFORCOM). The commander is known as COMNAVSURFLANT, and his or her headquarters are in Norfolk, Virginia.

Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (SURFPAC) administers to the needs and ensures the readiness of all surface ships assigned to the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The commander is known as COMNAVSURFPAC, and his or her headquarters are in San Diego, California.

Naval Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (SUBLANT) administers to the needs and ensures the readiness of all submarines assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. This commander is known as COMNAVSUBLANT, and his or her headquarters are in Norfolk, Virginia.

Naval Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (SUBPAC) administers to the needs and ensures the readiness of all submarines assigned to the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. This commander is known as COMNAVSUBPAC, and his or her headquarters are in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Naval Air Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (AIRLANT) administers to the needs and ensures the readiness of all aircraft assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. This commander is known as COMNAVAIRLANT, and his or her headquarters are at Norfolk, Virginia.

Naval Air Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (AIRPAC) administers to the needs and ensures the readiness of all aircraft assigned to the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. This commander is known as COMNAVAIRPAC, and his or her headquarters is at North Island, California.

Even though there are separate type commanders on the different coasts, for coordination purposes, one is senior to the other and ensures compatibility of resources and procedures. For example, COMNAVSURFLANT is a three-star admiral and COMNAVSURFPAC is a two-star, the latter in charge of surface activities in the Pacific, yet deferring to her or his counterpart on the Atlantic to ensure coordinated action. This was not always the case, so that Sailors moving from one coast to the other often encountered very different rules and procedures.

Other Components in the Administrative Chain of Command. Below the type commanders are group commanders and below them are ship squadron commanders or air wing commanders. For example, below COMNAVSURFLANT is Commander Naval Surface Group 2 with Destroyer Squadrons (DESRON) 6 and 14. Do not look for any regular pattern in these numbering systems, except that components on the East Coast are generally even-numbered and components on the West Coast are odd-numbered. The key point: just because Surface Group 2 has DESRONs 6 and 14 does not mean it will also have those numbers in between.

COMPLICATED BUT FUNCTIONAL

As you can see from the above, the Navy’s organization is indeed complicated. But considering all that must be done to keep the world’s most powerful Navy ready and able to carry out a very wide variety of missions, that organization is capable of meeting the many needs of the fleet as it serves the much larger defense establishment that guards the nation’s vital interests and keeps Americans safe.

N-codes and task unit designations with multiple decimal points may seem intimidating at first, but those who operate within them are soon comfortable with it all. Once you are assigned to a specific command, you will quickly learn those parts of the chains of command that are important to you, and you will soon be using the Navy’s alphabet soup of terminology with the best of them.

While it is good to be aware of these things early in your time in the Navy, you are likely to be more concerned about your immediate chain of command. The majority of Sailors will spend their early years on board a ship or a submarine, or in an aircraft squadron. The following sections explain those organizations in some detail.

SHIP AND SQUADRON ORGANIZATION

Because the missions and number of people assigned differ for each type of ship or aircraft squadron, each one is organized differently. An aircraft carrier, for example, has more departments and divisions than a destroyer, which is much smaller and has fewer people assigned. An aircraft carrier has need of an air department, but a submarine does not.

Despite these differences, all ships and squadrons have certain things in common. All commissioned ships and aircraft squadrons have a commanding officer who has overall responsibility and an executive officer who is second in command. All are divided into departments, and these are in turn subdivided into divisions.

![[8.10] Different types of...](../images/f0188-01.jpg)

Ships

Every Navy ship operates under the authority of an officer assigned by BUPERS as that ship’s commanding officer. The CO, as she or he is sometimes known, may be a lieutenant if the vessel is small, or a captain if the ship is very large. But no matter what the rank, the commanding officer is always called “Captain.”

In case of absence or death, the CO’s duties are assumed by the line officer next in command, whose official title is executive officer. The XO, as he or she is often called, is responsible for all matters relating to personnel, ship routine, and discipline. All orders issued by the XO have the same force and effect as though they were issued by the CO.

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANTS

Depending on the size of the ship, certain officers and enlisted personnel are detailed as executive assistants. All answer to the XO, but some, such as the ship’s secretary, will work directly for the captain in some matters. These jobs may be full-time assignments or may be assigned to individuals as collateral (secondary) duties, depending upon the size of the ship’s crew. Some are always filled by officers, others always filled by enlisted, but many can be either. Even those with “officer” in the title are sometimes filled by qualified enlisted personnel. A lot depends upon the size of the command and the relative qualifications of the individuals concerned.

The executive assistants are listed below in alphabetical order for convenience. Those listed are the most common; there may be others on board your ship as well.

Administrative Assistant. This individual can be an officer or a senior petty officer, and his or her duties are to relieve the XO of as many administrative details as possible. This individual will, under the XO’s guidance, manage much of the ship’s incoming and outgoing correspondence, take care of routine paperwork, and assist the XO with various other administrative functions.

Chaplain. Normally assigned only to larger ships, this specially qualified staff corps officer’s duties are primarily religious in nature, but she or he is also involved in matters pertaining to the mental, moral, and physical welfare of the ship’s company.

Chief Master-at-Arms. The chief master-at-arms (CMAA) is responsible for the maintenance of good order and discipline. The CMAA enforces regulations and sees that the ship’s routine is carried out. This duty is normally carried out by a chief petty officer.

Career Counselor. The career counselor runs the ship’s career-counseling program and makes sure that current programs and opportunities are known and available to crewmembers. His or her job is to stay informed about all of the Navy’s current programs affecting the actual or potential careers of the men and women in the ship’s crew.

Drug/Alcohol Program Adviser. Every Navy command is required to have at least one drug and alcohol program adviser (DAPA) on board. In larger commands, there should be one DAPA for every three hundred personnel assigned. DAPAs advise the CO and XO on the administration of the drug and alcohol abuse program aboard ship and on the approaches necessary to cope effectively with any problems that may exist in this area. The adviser must stay informed on all Navy policies and procedures on drug and alcohol education, rehabilitation, identification, and enforcement.

Educational Services Officer. The educational services officer (ESO) assists the XO in administering and coordinating shipboard educational programs for crewmembers.

Lay Leaders. When a chaplain is not available to meet the individual needs of crewmembers, a lay leader is appointed. For instance, if a unit has a Protestant chaplain, but no priest or rabbi, the command may appoint Roman Catholic and Jewish lay leaders. Those appointed must be volunteers, either officer or enlisted, and will receive appropriate training.

Legal Officer. The legal officer is an adviser and staff assistant to the CO and XO on the interpretation and application of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), the Manual for Courts-Martial (MCM), and other laws and regulations concerning discipline and the administration of justice within the command.

Personnel Officer. Assisting the XO in personnel matters, the personnel officer is responsible for the placement of enlisted personnel and for the administration and custody of enlisted personnel records. She or he will supervise the personnel office (if there is one) and oversee the processing of all enlisted performance evaluations, leave papers, identification cards, and transfer orders.

Postal Officer. The postal officer looks after the administration of mail services to the command. He or she must learn and stay current on all applicable postal regulations and supervise those personnel who handle the ship’s mail.

Public Affairs Officer. The public affairs officer prepares briefing material and information pamphlets, assists with press interviews, generates newsworthy material about the unit’s operation, and publishes the command’s newspaper.

Safety Officer. On ships that do not have safety departments, the safety officer will advise the CO and XO on matters pertaining to safety aboard ship. She or he will be accorded department-head status for safety matters and will coordinate the ship’s safety program.

Command Master Chief. The command master chief (CMDMC) assists the CO in matters of morale and crew welfare. See Chapter 5 for more detail.

Senior Watch Officer. The senior watch officer is responsible for assigning and supervising all deck watchstanders, under way and in port. He or she coordinates the ship’s watch bill, ensuring that trained personnel are equitably assigned to all necessary stations under all conditions. The senior watch officer is usually the most senior person among those who are standing watches.

Ship’s Secretary. Administering and accounting for correspondence and directives, and maintaining officers’ personnel records, are among the responsibilities of the ship’s secretary. He or she also supervises the preparation of the captain’s official correspondence.

Training Officer. The training officer coordinates the ship-wide training program. He or she will obtain and administer school quotas, provide indoctrination training to newly arrived personnel, coordinate with the operations officer in scheduling training exercises, and supervise the ship’s personnel qualifications system (PQS).

Security Manager. The security manager is responsible for information systems and personnel security, the protection of classified material, and security education.

3-M Coordinator. The various aspects of the ship’s maintenance and material management (3-M) program are supervised by the 3-M coordinator.

DEPARTMENTS AND DIVISIONS

Different ships have different departments, depending upon their size and mission. Some examples of commonly seen departments are engineering, operations, and supply. Ships whose primary mission is combat may have a weapons department, or it may be called combat systems on more sophisticated ships. Ships whose primary mission is logistical—involving replenishment of fuel, ammunition, or other supplies at sea—will often have a deck department.

Departments are subdivided into divisions, and divisions are often further subdivided into work centers, watches, and sections, with petty officers in charge of each.

Each ship’s department has a department head, an officer who is responsible for its organization, training, and performance. The larger the ship, the more senior the department head will be. In a destroyer the department head is often a senior lieutenant, while in aircraft carriers department heads are usually commanders or lieutenant commanders.

Departments are often divided into divisions and have a division officer responsible for them. The division is the basic working unit of the Navy. It may consist of twenty specialists on small ships or as many as several hundred persons in an aircraft carrier. The division officer is the boss; he or she reports to the department head and is frequently a junior officer but can be a chief petty officer or a more senior petty officer if the situation calls for it. The division officer is the one officer with whom division personnel come into contact every day. The division chief and the leading petty officer are the division officer’s principal assistants. Larger divisions may have more than one chief assigned and may even have other junior officers assigned as assistants.

In the first chapter of this book, you read about the chain of command, learning that it changes from assignment to assignment. When you report to your first ship, you will have a new chain of command that might begin with your section leader or work center supervisor, who reports to the division chief, who in turn reports to your division officer, who answers to the department head, whose boss is the executive officer, who reports directly to the captain, and so on.

Departments aboard ship belong to one of three different categories: command, support, or special.

COMMAND DEPARTMENTS

Depending upon the type of ship, some of the command departments frequently found on board are air, aircraft intermediate maintenance, combat systems, communications, deck, engineering, executive, navigation, operations, reactor, and/or weapons.

Air. The Air Department is headed by the air officer (informally referred to as the “air boss”), who supervises and directs launchings, landings, and the handling of aircraft and aviation fuels.

On a ship with only a limited number of aircraft, the department consists of a V division with the V division officer in charge. On ships with large air departments, additional divisions are assigned: V-1 (plane handling on the flight deck), V-2 (catapults and arresting gear), V-3 (plane handling on the hangar deck), V-4 (aviation fuels), and V-5 (administration). The division officers responsible for the first four divisions are known as the flight deck officer for V-1, the catapult and arresting gear officer for V-2, the hangar deck officer for V-3, and the aviation fuels officer for V-4.

Aircraft Intermediate Maintenance. The head of this department (usually referred to simply as “AIMD”) is the aircraft intermediate maintenance officer, who supervises and directs intermediate maintenance for the aircraft on board the ship. The AIMD also keeps up ground-support equipment. When there is only one division in the department, it is called the IM division. Ships having more than one division include the IM-1 division (responsible for administration, quality assurance, production and maintenance/material control, and aviation 3-M analysis), the IM-2 division (for general aircraft and organizational maintenance of the ship’s assigned aircraft), the IM-3 division (for maintenance of armament systems, precision measuring equipment, and aviation electronic equipment, known as “avionics”), and the IM-4 division (for maintenance of other aviation support equipment).

Combat Systems. Because of their complexity and sophistication, submarines and certain classes of cruisers, destroyers, and frigates have a combat systems department instead of a weapons department. Some of the functions covered by the operations department on those ships with a weapons department are included in combat systems on these vessels. Some of the divisions found in these departments are CA (antisubmarine warfare), CB (ballistic missile), CD (tactical data systems), CE (electronics repair), CF (fire control), CG (gunnery and ordnance), CI (combat information), and CM (missile systems).

Communications. In ships large enough to have a communications department, the head of the department is the communications officer, who is responsible for visual and electronic exterior communications. Her or his assistants may include a radio officer, a signal officer, a communications security material system (CMS) custodian, and a cryptosecurity officer. The department may be divided into CR (for radio) and CS (for signals) divisions. In smaller ships, the communications officer is a division officer reporting to the operations officer. In this case, the division is usually called OC division.

Deck. Some ships, such as aircraft carriers, have both a deck department and a weapons department; other ships have only one or the other, depending upon their mission. On ships with a deck department, the first lieutenant is the head of that department. which consists of divisions called 1st Division, 2nd Division, and so on. On ships that do not have a deck department, there is a division in the weapons department, usually called 1st Division, and the first lieutenant in this case is a division officer rather than a department head. Aboard those ships having only a deck department and not a weapons department, ordnance equipment, small arms, and other weapons are the responsibility of a division headed by a gunnery officer. Personnel assigned to the deck department (or division) carry out all seamanship operations, such as mooring, anchoring, and transferring cargo from ship to ship while under way.

Engineering. This department, headed by the engineering officer (also called the chief engineer), is responsible for the operation and maintenance of the ship’s machinery, the provision of electrical power and freshwater, damage control, hull and machinery repairs, and the maintenance of underwater fittings. Ships large enough to have more than one division in the engineering department might have an M or MP division for main propulsion, A for auxiliaries, E for electrical, IC for interior communications, and R division for repair.

Executive. Some ships have an executive department made up of one or more divisions. (Aircraft carriers have an administrative department, which is similar in nature and function to the executive department in other ships.) This department is headed by the XO and may have an X division, which includes personnel assigned to work in the CO’s office, XO’s office, chaplain’s office, print shop, security office, training office, legal office, and sick bay (when no medical officer is assigned). It may also include an I division used for the indoctrination of newly reporting personnel.

Navigation. This department, headed by the navigator, is responsible for the ship’s safe navigation and piloting and for the care and maintenance of navigational equipment.

Operations. This department, often called “Ops,” is headed by the operations officer, who is responsible for collecting, evaluating, and disseminating tactical and operational information. For ships with more than one division, the department might include OA, OC, OD, OE, OI, OP, OS, and OZ divisions. OA includes intelligence, photography, drafting, printing and reproduction, and meteorology. OC handles communications, but on ships having a large air contingent, such as aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, OC is the carrier air-traffic-control-center division. OD division covers the data-processing functions. OE is the operations electronics/material division. OI includes the combat information center (CIC) and sometimes the lookouts. OP is the photographic intelligence division. OS division handles communications intelligence. OZ is the intelligence and cryptologic operations division.

The following officers, when assigned, will usually report to the Ops officer: air intelligence, CIC officer, communications (COMM) officer, electronics material officer (EMO), electronic warfare (EW) officer, intelligence officer, meteorological officer, photographic officer, strike operations officer, and computer programmer (or computer-maintenance officer).

Reactor. Because they are nuclear powered, CVNs have this department in addition to the engineering department. The reactor officer, who heads this department, is responsible for the operation and maintenance of reactor plants and their associated auxiliaries. Divisions found in the reactor department include RA (auxiliaries), RC (reactor control), RE (electrical), RL (chemistry), RM (machinery), and RP (propulsion). Because of the special responsibilities of running a reactor plant and its obvious close ties with the engineering functions of the ship, the reactor and engineering officers must closely coordinate their activities.

Weapons. The weapons officer supervises and directs the use and maintenance of ordnance and (in ships without a deck department) seamanship equipment. On ships with antisubmarine warfare (ASW) arms and a weapons department, the ASW officer is an assistant to the weapons officer. Other assistants, depending upon the ship and its weapons capabilities, are the missile officer, gunnery officer, fire-control officer, and nuclear weapons officer. On some ships, the CO of the Marine detachment may also answer to the weapons officer.

Some of the divisions that may be included in the weapons department are F division (fire control), F-1 (missile fire control), F-2 (ASW), F-3 (gun fire control), G (ordnance handling), GM (guided missiles), V (aviation, for ships without an air department but with an aviation detachment embarked), and W (nuclear weapons assembly and maintenance).

SUPPORT DEPARTMENTS

Because of its obvious importance, most Navy ships will have a supply department. Smaller ships will have one or more hospital corpsmen assigned to handle the medical and health needs of the crew, but larger ships will have a medical department and a dental department with one or more doctors, dentists, nurses, and medical service corps officers assigned. Ships with one or more judge advocate general (lawyer) officers on board will have a legal department.

Supply. Headed by the supply officer, this department handles the procurement, stowage, and issue of all the command’s stores and equipment. The supply officer pays the bills and the crew and is responsible for supervising and operating the general and wardroom messes, the laundry, and the ship’s store. Ships large enough to have multiple divisions may have an S-1 division (general supply support), S-2 division (general mess), S-3 division (ship’s stores and services), S-4 division (disbursing), S-5 division (officers’ messes), S-6 division (aviation stores), and S-7 division (data processing).

Medical. The medical officer is responsible for maintaining the health of personnel, making medical inspections, and advising the CO on hygiene and sanitation conditions. Assistant medical officers may be assigned. H division is normally the only medical division.

Dental. The dental officer is responsible for preventing and controlling dental disease and supervising dental hygiene. Assistant dental officers are sometimes assigned to larger ships. D division is normally the only dental division.

Legal. The legal officer is responsible for handling all legal matters, particularly those pertaining to the UCMJ.

SPECIAL DEPARTMENTS

Certain ships have unusual missions and therefore require special departments. Included among these are aviation, boat group, deep submergence, repair, safety, transportation, and weapons repair.

Aviation. On a nonaviation ship with a helicopter detachment embarked, an aviation department is organized and headed by the aviation officer. The aviation officer is responsible for the specific missions of the embarked aircraft. His principal assistant may be a helicopter control officer, but often one officer performs both functions.

Boat Group. Amphibious ships often have a boat-group department whose responsibilities include the operation and maintenance of the embarked boats.

Deep Submergence. This specialized department, which is found on only a few naval vessels, launches, recovers, and services deep-submergence vehicles (DSVs) or deep-submergence rescue vehicles (DSRVs).

Repair. On ships with a large repair function, there will be a full department with a department head called the repair officer. On multiple-division ships, there may be an R-1 division (hull repair), R-2 division (machinery repair), R-3 division (electrical repair), R-4 division (electronic repair), and R-5 division (ordnance repair).

Safety. Larger ships, particularly those that conduct potentially hazardous operations on a routine basis, will have a safety department assigned.

Transportation. Only Military Sealift Command (MSC) transports have this department, headed by the transportation officer. The department is responsible for loading and unloading, berthing and messing, and general direction of passengers. On ships without a combat cargo officer, the transportation officer is also the liaison with loading activities ashore. Larger ships may have a T-1 division, which has the physical transportation responsibilities, and a T-2 division, which handles the administrative end of transportation.

Weapons Repair. This department, found only on tenders, usually has a single division, designated SR. A large department may be subdivided into the SR-1 division (repair and service) and the SR-2 division (maintenance of repair machinery).

AIRCRAFT SQUADRONS

Operating squadrons, like ships, have a CO, an XO, department heads, and division officers.

Commanding Officer

The CO, also known as the squadron commander, has the usual duties and responsibilities of any captain insofar as they are applicable to an aircraft squadron. These include looking after morale, discipline, readiness, and efficiency and issuing operational orders to the entire squadron.

Executive Officer

The XO, the second senior naval aviator in the squadron, is the direct representative of the CO. The XO sees that the squadron is administered properly and that the CO’s orders are carried out. The executive officer, as second in command, will take over command of the squadron whenever the CO is not present.

Squadron Departments

Operational squadrons are organized into several departments, each with its own department head who is responsible for organization, training, personnel assignments, departmental planning and operations, security, safety, cleanliness of assigned areas, and maintenance of records and reports. Just as in ships, the number and functions of departments vary somewhat according to the squadron’s mission. Most squadrons have at least four departments: operations, administration, maintenance, and safety. Many have a training department as well.

OPERATIONS

This department is responsible for aircraft schedules, communications, intelligence, navigation, and (in squadrons without a separate training department) squadron training. Working for the operations officer are a number of assistants with special duties, including the communications officer, classified material security officer, intelligence officer, navigation officer, tactics officer, landing signal officer, and (in squadrons without a separate training department) several training assistants.

ADMINISTRATIVE

The administrative department is responsible for official squadron correspondence, records maintenance, legal matters, and public affairs. An officer designated as first lieutenant ensures that squadron spaces and equipment are maintained and clean. Other assistants to the admin officer are the personnel officer, educational services officer, public affairs officer, legal officer, and command security manager. The personnel division takes care of personnel records, human resources management, and equal opportunity programs.

MAINTENANCE

This department is typically the largest in the squadron and oversees the planning, coordination, and execution of all maintenance work on aircraft. It also is responsible for the inspection, adjustment, and replacement of aircraft engines and related equipment including survival gear, as well as the keeping of maintenance logs, records, and reports.

SAFETY

The safety department head ensures squadron compliance with all safety orders and directives and is a member of the accident (investigation) board. The quality assurance division within the safety department is responsible for the prevention of defects by ensuring command compliance in programs and policies applicable to each aircraft platform.

TRAINING

Some squadrons have separate training departments to handle the training requirements of the squadron. Squadrons designated as fleet replacement squadrons (once known as readiness air groups or RAGs) exist to train new or returning squadron personnel in preparation for assignment to operational squadrons. Pilots and naval flight officers train in these squadrons after their initial basic flight training and before returning to an operational squadron after an extended assignment to other duties. Enlisted maintenance personnel are also trained in these squadrons in a special program known as FRAMP (Fleet Readiness Aviation Maintenance Personnel). Sometimes there is a separate FRAMP department.

![]()

The Navy’s organization is complex and often confusing. While it is important for you to know your immediate organization and perhaps several levels above and below, you will not need to know all aspects. When you report to a new duty station, one of your early priorities should be to learn the organization of your new command and where it fits into the larger Navy. Rank and experience will determine how much else you will need to know.