For mating intelligence to be a useful psychological idea, a valid measure was needed. Fortunately, we got the phone call from Psychology Today that provided the encouragement to develop a way for people to test themselves. In 2006, Kaja Perina, Editor-in-Chief of Psychology Today, contacted us about our work on mating intelligence. She indicated that she was planning to write a cover story all about mating intelligence.1 Along with the article, Kaja thought it would be good to include some measure of mating intelligence that readers of the magazine could take so as to better understand where they stacked up. “Yes, absolutely!” we responded. This sounded like fun!

So the Mating Intelligence Scale2 was initially designed as a fun scale made for a popular magazine—not created with an academic agenda. However, as two psychometrically trained research psychologists, we created the scale using the same kind of reasoning that would go into any scale we were creating for research purposes.

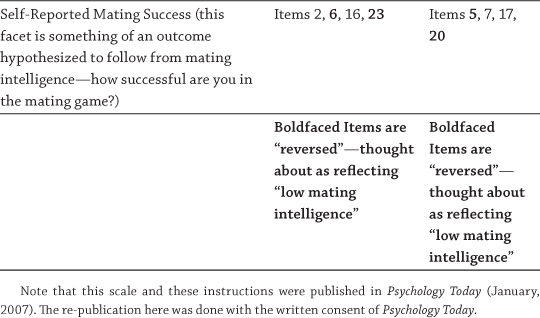

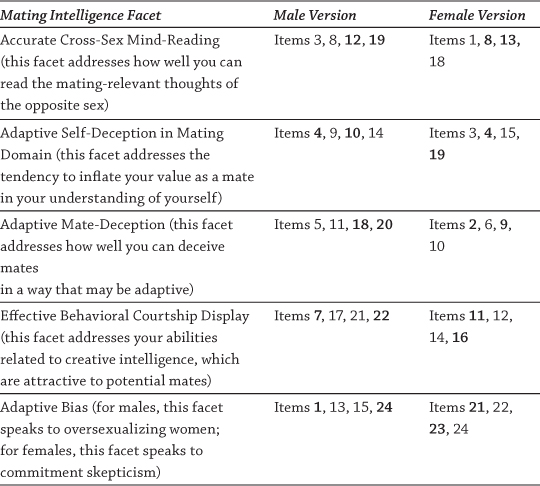

In creating the scale, we first considered the core aspects of mating intelligence. By this point in the book, you shouldn’t be surprised by the concepts we include as facets (or subscales) of the main scale. These facets include processes that we consider core to our understanding of mating intelligence. Below is a description of each facet along with an example item from the True-or-False Mating Intelligence Scale that corresponds to that facet:

1. Accurate Cross-Sex Mind-Reading (this facet addresses how well you can read the mating-relevant thoughts of the opposite sex)

Sample item: I can tell when a man is being genuine and sincere in his affections toward me.

2. Adaptive Self-Deception in the Mating Domain (this facet addresses the tendency to inflate your value as a mate in your understanding of yourself)

Sample item: I look younger than most women my age.

3. Adaptive Mate-Deception (this facet addresses how well you can deceive mates in a way that may be evolutionarily adaptive)

Sample item: If I wanted to make my current guy jealous, I could easily get the attention of other guys.

4. Effective Behavioral Courtship Display (this facet addresses your abilities related to creative intelligence, which are attractive to potential mates)

Sample item: I’m definitely more creative than most people.

5. Adaptive Perceptual Bias (this facet is sex differentiated; for males, items that tap this facet address the tendency toward oversexualizing females; for females, items that tap this facet reflect commitment skepticism)

Sample female item: Most guys who are nice to me are just trying to get into my pants.

Sample male item: Women tend to flirt with me pretty regularly.

6. Self-Reported Mating Success (this facet is something of an outcome hypothesized to follow from mating intelligence—how successful are you in the mating domain?)

Sample item: I attract many wealthy, successful men.

Therein lies the reasoning underlying the structure of the Mating Intelligence Scale.3 Later in this chapter, we include the full test (both the male and female versions) along with a scoring key and commentary on how to interpret results. We also include comments on specific people who have scored at different levels of the range on this scale.

Whenever we talk about mating intelligence, we have to keep in mind Darwin’s bottom line. Remember, Darwin described adaptations as producers of evolutionary forces that facilitate the reproductive success of an organism. Typically, biologists will study the number of offspring produced by an organism as a measure of that organism’s fitness. We can’t do that very easily with modern humans. Modern humans have plentiful forms of birth control that did not exist during the lion’s share of human evolutionary history. A person with all the hallmarks of an evolutionary success story might just be dynamite at using condoms properly—and leave no descendants.

As scientists studying human psychology from an evolutionary perspective, the best we can do, then, really, is to approximate reproductive success. Work along these lines has begun in evolutionary psychology labs around the world.4 In measuring mating success, we essentially need to think about tapping outcomes that would have been associated with ultimate reproductive fitness under ancestral conditions. In light of Trivers’5 parental investment theory, we realized that any index of mating success must be sex differentiated because, for example, a male who copulates at high frequencies will gain fitness benefits while a female will not gain any fitness benefits from such a strategy. Work on creating optimal measures of mating success is still in progress and will likely never fully approach the elusive variable of reproductive success in postcontraceptive human societies. But given the cards in our hand, measuring indices of mating success is currently the best way to examine the validity of any tests designed to measure mating intelligence.

Initially, the scale was created for fun, and although we put some good thought into the creation of this scale, scientific validation was not on our initial radar. Still, the scale took on something of a life of its own. The issue of Psychology Today that published the scale, we were told, ended up being one of the best-selling issues in the magazine’s history. The article was picked up by several other media outlets—Arts and Letters Daily, The New Scientist, The Washington Times, and more. Not to mention the hundreds of blogs and OK Cupid.

At some point, several researchers affiliated with Binghamton University’s world-renowned evolutionary studies program, directed by David Sloan Wilson, became interested in this scale. Dan O’Brien, then a PhD student in Biology with a concentration in evolutionary studies at Binghamton, asked us if he could include this scale (along with other evolutionarily relevant scales) to administer to undergraduate students at Binghamton. We were delighted.

A few months later, we got an intriguing email from Dan. Were we aware that our Mating Intelligence Scale better predicted several sexual outcomes than any of the other scales used in their study? This suggested that the scale must have some scientific validity and significant predictive validity. Considering the humble origins of the scale, this was exciting news.

Since then, several studies have been conducted (and published) on the scientific merit of the Mating Intelligence Scale.6 This first study, done in conjunction with Dan O’Brien, Andy Gallup, and Justin Garcia at SUNY Binghamton, examined the reliability, validity, and predictive utility of the Mating Intelligence Scale. It was administered to more than 100 undergraduate males and females—along with several measures of sexual activity, including (1) age at first sexual intercourse, (2) number of sex partners in the past year, and (3) number of lifetime sex partners.

In this study,7 the Mating Intelligence Scale was psychometrically examined in two important ways. First, an analysis was conducted to see whether the different subscales are “internally reliable” and “distinct”—that is, do the statistics bear out our prediction that the facets of mating intelligence that we built into the scale really are distinct and reliable facets of this concept? Short answer: not necessarily—the subscales generally showed relatively low internal reliability. That is, this initial analysis did not provide strong evidence that this measure scientifically breaks down into these facets. However, we then conducted a reliability analysis on the full scales—for both the male and female versions—and found the full scales did, indeed, demonstrate strong internal reliability. So we essentially found that the full scales are reliable scales—and we could make the case that we are measuring overall mating intelligence (while not necessarily measuring each facet of mating intelligence). At least we had evidence that we had strong and psychometrically verified full scales of mating intelligence for each of the sexes.

We then go on to our research questions to address the validity of mating intelligence: Does mating intelligence predict sexual behavior for males and females—and does it do so in a way that makes evolutionary sense?

Things played out a bit differently for each of the sexes. As such, analyses were conducted separately for men and women. For males, high mating intelligence corresponded to having sex relatively early in life, having a relatively high number of lifetime sexual partners, and having a relatively high number of partners in the past year. Consistent with much past research on male mating psychology from an evolutionary perspective,8 success in the mating domain for males corresponds to a relatively high number of sexual partners.

Mating psychologists have consistently shown that mating psychology is often highly sex differentiated.9 For mating intelligence to be valid within this sphere of academia, it makes sense, then, that the Mating Intelligence Scale would predict outcomes in a sex-differentiated manner that are consistent with the large body of past work in this area. Female mating psychology tends to be more complex, on average, than male mating psychology,10 and a good measure on mating psychology should catch this important nuance.

Sure enough, in predicting these basic sexual outcomes, the Mating Intelligence Scale does exactly this. Females who scored high on the Mating Intelligence Scale showed a slightly different pattern from males who scored high on this scale—and a pattern that makes good evolutionary sense. Females who scored high (1) had sex relatively early in their lives and (2) had a higher number of lifetime sex partners compared with females who scored low. Importantly, this second outcome, having more lifetime sexual partners, is explainable as a statistical artifact that follows from having a longer lifetime sexual history. Importantly, females who scored high on the Mating Intelligence Scale did not report more sexual partners in the past year compared with other females. This pattern is different from what was found with males (which was simply, more mating intelligence, more partners), and it reflects the complexities of female sexuality. For a female, high mating intelligence may well increase with early sexual experiences, but it may also ultimately shape a behavioral pattern that is highly discriminating in mate selection.

In a more recent study that we are conducting with our colleagues Ben Crosier and James C. Kaufman, we gave out the Mating Intelligence Scale to hundreds of young men and women in an ethnically diverse sample of students in California. Along with the Mating Intelligence Scale, participants in this study completed a measure of general intelligence,11 and measures of the most scientifically accepted personality traits there are—the Big Five personality traits of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Decades of intensive research on the nature of the basic personality traits has led to the determination that these five trait dimensions reflect significant aspects of people that discriminate individuals from one another. From a scientific perspective, these are considered the five most robust personality traits. With the addition of general intelligence, which is also, clearly, a major dimension of human variation, psychologist Geoffrey Miller12 refers to these dimensions as the Central Six (the Big 5 plus general intelligence).

In our study, a measure of mating success, including items related to short-term mating success (such as being able to turn up short-term partners easily) and long-term mating success (such as currently being in a satisfying long-term relationship), was also presented to participants.

We hope that this study represents a crucial step in terms of the validation of mating intelligence. If the Mating Intelligence Scale has predictive validity, then it should predict this evolutionarily important outcome (mating success) in a way (1) that is distinct from the ability of the Central Six to predict mating success and (2) that leads to predictions of significant amounts of variability in mating success. In short, this all means that scores on the Mating Intelligence Scale should be related to scores on the mating success scale, and if the Mating Intelligence Scale is valid, scores on this scale should be more related to mating success than scores on the general intelligence measure or scores on the Big 5 personality traits.

After a series of advanced statistical analyses (including a process called multiple regression) conducted by the formidable Ben Crosier as part of his master’s thesis, the data were clear: the Mating Intelligence Scale emerged as the single best predictor of mating success for both males and females.

From an evolutionary perspective, this finding is, actually, quite enormous. Darwin’s bottom line is clear. Organisms are in natural competition for reproduction into subsequent generations. From a Darwinian perspective, the ultimate outcome variable is reproductive success. As we’ve discussed earlier in this book, reproductive success (number of offspring and grand-offspring) cannot be tapped in a meaningful way in modern societies owing to the large-scale use of contraception. The best that we can do to approximate reproductive success in modern humans is to measure mating success, which should include outcomes and behaviors that would have led to increased reproductive success under ancestral conditions.13 We believe that predicting mating success is crucial for any psychological variable posited to have evolutionary relevance. And compared with general intelligence and the Big 5—representing, in composite, the most intensively studied and validated constructs in all of personality psychology—mating intelligence best predicts mating success.

Since this large-scale validation study, several advanced students in the SUNY New Paltz Evolutionary Psychology Lab have found in their own studies that the Mating Intelligence Scale continues to predict important life outcomes. Haley Dillon examined mating intelligence as it relates to narcissism and found that there is a slight positive correlation between narcissism and mating intelligence for both sexes (although females score higher on narcissism than do males). This capacity may entail a bit of self-absorption, but not too much.

Ashley Peterson, another graduate student in the SUNY New Paltz Evolutionary Psychology Lab, gave the Mating Intelligence Scale to undergraduate students along with measures of the Big Five personality traits, and asked participants for their degrees of preference for various sexual acts. Interestingly, mating intelligence was positively related to preferences for several acts but was mostly predictive of a preference for vaginal intercourse over oral or anal intercourse; this finding was pronounced for females in the sample.14 Mating intelligence also tended to correspond to being relatively extraverted, which we know from Chapter 3 is associated with a proclivity toward sexual variety (although introverts can certainly score high in mating intelligence and have an active sex life).

In another recent study conducted by Daniel O’Brien and his colleagues,15 the Mating Intelligence Scale was shown to play an important predictive role regarding a common and socially relevant class of modern mating behavior: hook-ups. Hook-ups are defined as casual mating experiences with no expectations of the creation of long-term bonds.16 Among college students, hook-up experiences are quite common. Although statistics vary from study to study and school to school, generally, it seems that a majority of college students report having engaged in some hook-up behaviors.

With an explicit focus on short-term mating, hook-up behaviors seem a bit evolutionarily strange in a relatively monogamous species such as ours. With this thought in mind, Justin Garcia and Chris Reiber17 conducted a study to explore the motivations underlying hook-up experiences. They came to find that most females who engage in hook-ups do, actually, hope that hook-up experiences will lead to long-term relationships. Interestingly, a majority of males who were included in this study reported the same thing! Contrary to what a lot of people think, males often expect and hope (probably privately) that hook-up experiences will lead to long-term relationships. Hook-up experiences and the emotions driving them are more complex than they might seem.

In a follow-up to Garcia and Reiber’s study,18 we explored the role of mating intelligence as it relates to hook-ups. At the suggestion of our colleague Melanie Hill, we decided to break hook-up experiences into three categories—because not all hook-ups are the same.

In this research, hook-up experiences were broken down as follows:

A. Type I: hook-up with a total stranger

B. Type II: hook-up with an acquaintance

C. Type III: hook-up with a friend

In this study, the Mating Intelligence Scale was given to a sample including about 200 male and female college students. Participants were also asked to report if they had engaged in any Type I, Type II, or Type III hook-ups.

Consistent with the study that predicted sexual activity from mating intelligence, two important general themes emerged. First, mating intelligence significantly predicted the outcome variables, providing further evidence that mating intelligence is strongly related to mating-relevant outcomes. Additionally, the pattern of relationship between mating intelligence and hook-up behaviors played out differently for males and females, in a way that makes sense in light of what we know about evolutionary psychology.

For males, the story remains the same. Males who had experienced any of the three kinds of hook-ups generally scored higher on the Mating Intelligence Scale than males who had not experienced the different kinds of hook-ups. For females, the results were much more nuanced. Females who had engaged in type I hook-ups (hook-ups with total strangers) were no different from other females in their Mating Intelligence Scale scores. Similarly, females who had engaged in type III hook-ups (hook-ups with “friends”) were no different from other females in their Mating Intelligence Scale scores. But females who had engaged in type II hook-ups (hook-ups with “acquaintances”) did score higher than other females on the Mating Intelligence Scale.

These findings speak to the kind of complexity underlying female sexuality that evolutionary psychologists have documented extensively.19 A female engaging in too many short-term flings, with no chance of commitment, is taking on an evolutionarily questionable strategy because she is at risk for being abandoned and facing exorbitant parental costs. It makes sense, then, that a female who is high in mating intelligence is not necessarily a female who is engaging in many short-term flings because such behavior would not be “intelligent” from a female mating perspective.

Further, based on published research regarding opposite-sex friendships,20 it makes sense that females would not be hooking up with men whom they assess as friends. Females are much more likely than males to see opposite-sex friends in nonsexual terms and to expect a circle of male friends to serve non-sexual benefits, such as providing a broader social network and protection. Once a female has designated a male as having friend status in her mind, a hook-up with that male would defeat much of the evolutionary purpose of that friendship. So, it might not make sense for a woman with high mating intelligence to have sex with her male friends.

A man defined as an acquaintance, however, might be precisely at a level that would be evolutionarily reasonable to hook-up with—particularly if hook-ups in females are really part of a strategy of turning up a high-quality long-term mate.21 And females with relatively high mating intelligence are more likely than other females to engage in these kinds of hook-ups.

All of these findings together suggest that the Mating Intelligence Scale has the potential to chart not only personality traits but also important mating-relevant life outcomes.

When the idea of mating intelligence first hit the streets, we’ll admit, there were some skeptics. Rightfully so. Any idea framed as a fresh new theory in the field of psychology should be met with a good bit of skepticism. Psychology has seen plenty of wheel reinventing in its history, and newly invented wheels aren’t often useful.

A common criticism that we heard echoes the most common criticism lobbed at emotional intelligence22 when it first emerged. What’s new here?

At this point in the book, we hope the reader will agree that there is actually quite a lot new here. Mating intelligence is not just “mating psychology” repackaged. Here, we’d like to draw attention to a particular innovation that follows from the idea of mating intelligence. In the past, mating researchers spent considerable time and energy trying to understand mating processes as optimized by evolutionary forces. Males show preference for females with a particular tone of voice23; women sort through a relatively high number of suitors before settling on a particular mate24; male jealousy responses are particularly sensitive to sexual prompts25; and so forth.

As we attempt to understand human nature, this research is illuminating. However, this past research all has a limitation that can actually be addressed by the idea of mating intelligence. Saying that some behaviors and processes are part of “human nature” does not speak to all the differences found among humans in these behaviors and processes. Sometimes, it’s more informative to look at the effects of different levels that exist among humans in order to come to a deeper understanding of a phenomenon.

As an example, consider commitment skepticism, documented by Martie Haselton and David Buss,26 defined as the evolutionarily adaptive tendency for females to be particularly skeptical of a man’s faithfulness or long-term intentions. Sure, this process typifies female mating psychology, and we have even documented it in our own research.27 But thinking about this process as a species-typical process says nothing about individual differences in this tendency.

It may well be the case that women in general are commitment skeptics, but consider the following issues:

1. Some women may be more commitment skeptical than others.

2. There may be an optimal amount of commitment skepticism for most effective mating success.

and

3. Having an optimal amount of commitment skepticism may go along with other psychological mating tendencies that are relatively intelligent (e.g., the ability to read effectively the behaviors, thoughts, and intentions of potential suitors).

A woman who is high in mating intelligence may well be a solid exemplar of commitment skepticism, just as a woman who is high in mating intelligence may well be an exemplar of strategic and optimized hook-up behavior and strategic and optimized sexual activity more generally.28

Future research on mating-relevant adaptations may do well to see whether high mating intelligence tends to correspond to a “relatively adaptive response.” In this way, mating intelligence scores may actually be used as a barometer of sorts, measuring whether a proposed mating-relevant adaptation is, indeed, something that typifies how mating experts behave.

Until this point, we’ve been trying to make the case that the Mating Intelligence Scale is pretty much the best thing since color TV. In reality, as is true with any scientific measure, this scale could benefit from some improvement. In this section, we’ll talk about the pros and cons of the scale as well as the future of psychometric work in this area.

Remember, the Mating Intelligence Scale was designed with a general audience in mind; we needed to then substantiate it scientifically. With that said, strong psychometric work has been published on this scale,29 and several studies have now demonstrated its ability to predict the kinds of mating outcomes that should be predicted by a measure of mating intelligence.30

But a great deal of work still needs to be done. First and foremost, the Mating Intelligence Scale has primarily been administered to college students. As we have repeatedly pointed out in this book, mating behaviors are very contextual, and age is an important factor in determining mating-relevant outcomes. Much more research needs to be conducted on how mating intelligence operates across the life span. It may eventually turn out that we need to have separate scales, one for young adulthood and another for adulthood. Or perhaps even more differentiated scales, such as one for senior citizens. Our grandparents are probably up to a lot more hooking-up behavior than we realize (or care to realize)!

Second, it seems that the Scale acts best as a total scale rather than as a set of facets or subscales. More research needs to be done to properly measure the various components of mating intelligence. This will require coming up with new items and getting rid of some of the older ones.

Third, the male and female versions are different. On the one hand, this makes sense given that male and female mating psychology is not the same. On the other hand, it makes for a classic apples-and-oranges problem. Because the two scales have largely different content, it is unclear whether they are tapping the same underlying concepts. Although our preliminary work in validating the scale suggests that the two versions do seem to behave similarly, this is still a point that researchers need to keep in mind.

Fourth, even though the Mating Intelligence Scale has been shown to be a valid and effective initial measure of mating intelligence, we believe that it just scratches the surface of the measurement of mating intelligence. The history of the measurement of emotional intelligence is complex,31 and we expect mating intelligence to go through a similar development. With emotional intelligence, two kinds of measures have been created—trait measures and ability measures.32 Trait measures include self-reports of emotional intelligence,33 whereas ability-based measures tap actual abilities in terms of dealing with emotions (such as the ability to guess which emotion best characterizes a particular response illustrated by an actor in a video).34

In terms of this trait/ability measure distinction, the Mating Intelligence Scale would be considered a trait measure. Research on emotional intelligence has often been critical of trait measures, suggesting that such measures are tapping personality traits as opposed to any kind of intelligence.35 Might this same kind of criticism make sense in terms of mating intelligence? Quite possibly—and this is certainly an important issue for future research on mating intelligence to take on.

In fact, in thinking about future research on mating intelligence, it becomes clear that developing valid ability-based indices of this construct sits at the forefront of future scientific work in this field. As examples, it would be great to be able to measure people’s actual abilities to successfully guess the mating-relevant thoughts of the opposite sex. Similarly, an ability-based measure of mating intelligence could examine individual differences in mating-relevant deception—are some people simply better at this skill than others? Can we operationally define differences in how well people can make a potential mate feel comfortable in a social setting? Can we measure how people differ in their abilities to convince a potential mate to go on a date? Can we measure individual differences in the ability to smooth things over during a moment of conflict within a long-term mateship using a combination of cognitive and emotional skills?

We believe that the Mating Intelligence Scale has proved very useful in paving the way for empirical research on this topic—but creating genuine ability-based measures of the different elements of mating intelligence certainly will lead to more insights into human nature and its many variations, in the future.36

A final concept to consider in deconstructing the Mating Intelligence Scale pertains to scoring low versus high. After this scale was published, you might imagine that we were busy having pretty much everyone we knew take the test. Scott’s Grandma took it—and scored off the charts. Glenn’s grandmother-in-law also scored in the upper echelon. A high-level administrator at SUNY New Paltz took it, but he came out as a bit mating challenged. Glenn’s brothers took it and scored pretty low. Glenn’s son Andrew scored slightly above the mean—Andrew is currently 7 years old! And so on …

Although we are confident in this scale having strong science behind it and being a great tool for research purposes, its usefulness in everyday life is still open for discussion. So take this scale with a grain of salt! But, with that said …

In this final section of this chapter, you’ll find the Mating Intelligence Scale (in full) along with a scoring key and a breakdown of which items go with which facets of mating intelligence. Have fun!

FOR MEN

1. ___ I think most women just like me as a friend.

2. ___ I have slept with many beautiful women.

3. ___ I’m pretty good at knowing if a woman is attracted to me.

4. ___ I’m definitely not the best at taking care of kids.

5. ___ I’m good at saying the right things to women I flirt with.

6. ___ I haven’t had as many sexual partners compared with other guys I know (who are my age).

7. ___ I have a difficult time expressing complex ideas to others.

8. ___ I am good at picking up signals of interest from women.

9. ___ I’m definitely near the top of the status totem pole in my social circles.

10. ___ I doubt that I’ll ever be a huge financial success.

11. ___ If I wanted to, I could convince a woman that I’m really a prince from some little-known European country.

12. ___ Honestly, I don’t get women at all!

13. ___ Women tend to flirt with me pretty regularly.

14. ___ If a woman doesn’t seem interested in me, I figure she doesn’t know what she’s missing!

15. ___ Women definitely find me attractive.

16. ___ I’ve dated many intelligent women.

17. ___ People tell me that I have a great sense of humor.

18. ___ When I lie to women, I always get caught!

19. ___ I am usually wrong about who is interested in me romantically.

20. ___ It’s hard for me to get women to see my virtues.

21. ___ At parties, I tend to tell stories that catch the attention of women.

22. ___ I’m not very talented in the arts.

23. ___ I can attract women, but they rarely end up interested in me sexually.

24. ___ When a woman smiles at me, I assume she’s just being friendly.

1. ___ I can tell when a man is being genuine and sincere in his affections toward me.

2. ___ I doubt I could ever pull off cheating on my beau.

3. ___ I look younger than most women my age.

4. ___ When a guy doesn’t seem interested in me, I take it personally and assume something is wrong with me.

5. ___ Good-looking guys never seem into me.

6. ___ I have a sense of style and wear clothes that make me look sexy.

7. ___ I attract many wealthy, successful men.

8. ___ Honestly, I don’t think I understand men at all!

9. ___ With me, a guy gets what he sees—no pretenses here.

10. ___ If I wanted to make my current guy jealous, I could easily get the attention of other guys.

11. ___ Men don’t tend to be interested in my mind.

12. ___ I’m definitely more creative than most people.

13. ___ I hardly ever know when a guy likes me romantically.

14. ___ I laugh a lot at men’s jokes.

15. ___ If a guy doesn’t want to date me, I figure he doesn’t know what he’s missing!

16. ___ I am not very artistic.

17. ___ My current beau spends a lot of money on material items for me (such as jewelry).

18. ___ I am usually right on the money about a man’s intentions toward me.

19. ___ I really don’t have a great body compared with other women I know.

20. ___ Intelligent guys never seem interested in dating me.

21. ___ I believe that most men are actually more interested in long-term relationships than they’re given credit for.

22. ___ Most guys who are nice to me are just trying to get into my pants.

23. ___ When it comes down to it, I think most men want to get married and have children.

24. ___ If I have sex with a man too soon, I know he will leave me.

How high is your mating intelligence? The Mating Intelligence Scale included here was created by us for a Psychology Today article on mating intelligence, published a few years ago. There are two versions, one for heterosexual males and one for heterosexual females. Each test is designed to provide a rough guide to your relationship effectiveness—not a definitive statement about individual character. To take the test, simply answer True or False for each of the 24 items under the test that pertains to you. Scroll to the end for scoring—and note that however you score, mating intelligence is a malleable dimension of human psychology!

FOR MALES

Give yourself one point for every T answer to questions 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 21. Add one point for every F answer to items 1, 4, 6, 7, 10, 12, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, and 24.

FOR FEMALES

Give yourself one point for every T answer to questions 1, 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 22, and 24. Add one point for every F answer to items 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 13, 16, 19, 20, 21, and 23.

______________

Based on a recent study (O’Brien et al., 2010), male scores tend to average about 12.3, whereas the female average is about 10.5. And there is a lot of variability in scores within each sex.