If monkeys have taught us anything, it’s that you’ve got to learn how to love before you learn how to live.”

If monkeys have taught us anything, it’s that you’ve got to learn how to love before you learn how to live.”

—Harry Harlow, psychologist (1961)

If monkeys have taught us anything, it’s that you’ve got to learn how to love before you learn how to live.”

If monkeys have taught us anything, it’s that you’ve got to learn how to love before you learn how to live.”

—Harry Harlow, psychologist (1961)

The scene is familiar: Your partner will be leaving for a few days to be with friends and family while you stay home to finish up some important work. The two of you have arrived at the airport, your partner has checked in, and you approach the point beyond which only passengers are allowed. You whisper sweet words to each other, kiss, snuggle a little, kiss again, start to walk away, return for one last hug, and then watch and wave as your partner goes through the gate. As you leave, you notice several others doing the same thing—staying together until the last possible minute, promising to reconnect as soon as possible.

Where most people might see nothing more than the loving exchanges of family members and intimate partners, proponents of attachment theory see something different (e.g., Fraley & Shaver, 1998). To them, these exchanges are outward indications of an attachment behavior system, an innate set of behaviors and reactions, shaped by evolution, that helps ensure our safety and survival. As you learned in Chapter 2, this system governs our capacity to form emotional bonds with others, motivates us to stay near our attachment figures, and causes us to restore our connection with them when a relationship is threatened, or when we feel anxious, ill, or otherwise distressed. Reestablishing the connection reduces tension, letting us feel calm, soothed, and supported. This is exactly what your behavior in the airport is designed to achieve, if only temporarily, as you manage the stress of separating from your partner.

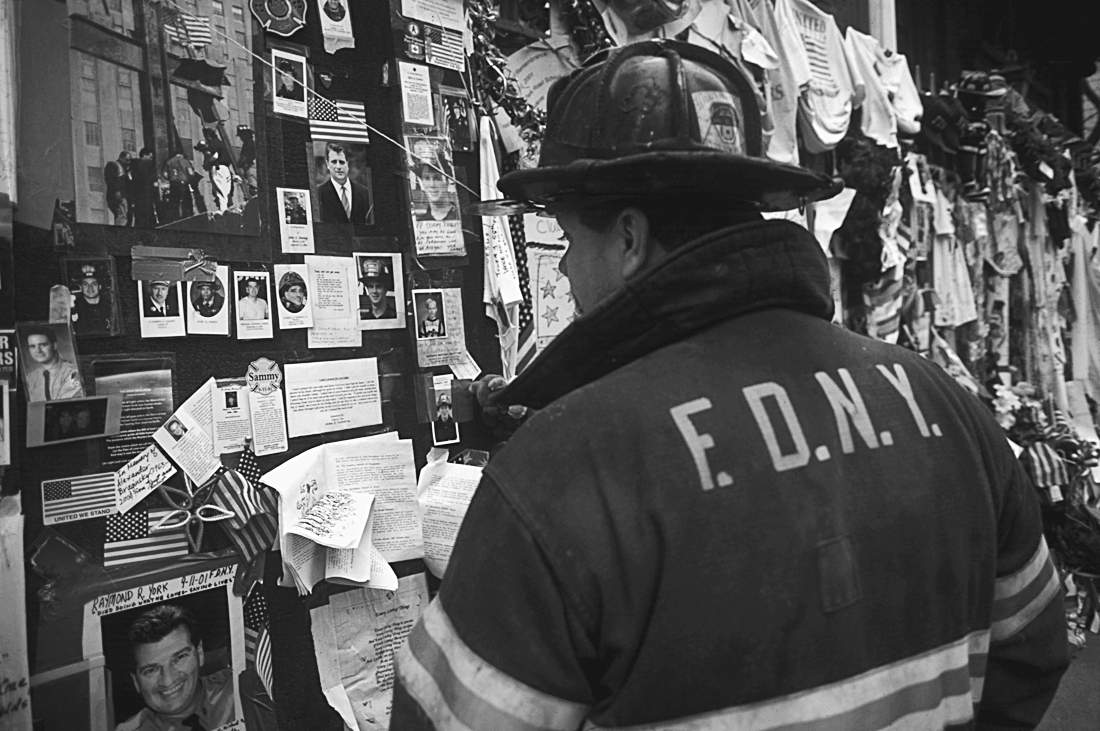

According to this view, evidence of the attachment behavior system is all around us: in day-care centers, when parents drop off and pick up their kids; in cemeteries, where families and friends mourn the deceased; in hospitals, where patients want to have their nearest and dearest around; and in times of great calamity, when partners and family members conduct searches to locate missing loved ones (Figure 6.8).

FIGURE 6.8 Attachment behavior systems at work. Following the 9/11 tragedy in New York in 2001, families and friends created a makeshift memorial at the World Trade Center in the hope of locating lost loved ones.

Surprisingly, the motivating nature of love and affection was not always recognized, nor were these emotions viewed as being beneficial to children’s development. In the first half of the 20th century, the early days of academic psychology were dominated by behaviorism, and by the view that dispassionate objectivity and principles of learning were the best way to understand and change human behavior. Emotions were seen as problems to be controlled, and the proper way to raise children was to shape their behavior by judiciously selecting rewards and punishments. Nurturing children, it was thought, only made them spoiled, needy, and dependent. Psychologist John Watson (1878–1958), father of behaviorism and an early president of the American Psychological Association, was particularly keen on separating children from their parents and then raising them without genuine affection, but according to “scientific” principles (Blum, 2002).

Pioneering studies by astute clinical observers and dedicated scientists—notably Harry Harlow, an American psychologist and graduate student of Lewis Terman in the 1920s; John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist; and Mary Salter Ainsworth, a developmental psychologist working in Canada—eventually overturned this view. Collectively, their work drew attention to the profound importance of caregiver-child attachments and to the enduring effects these bonds had on how individuals viewed themselves and others over the course of their lives. Attachment theory therefore provides us with another perspective on individual differences, and how those differences come to affect partners in their intimate relationships.

We do as we have been done by.”

We do as we have been done by.”

—John Bowlby, psychiatrist

Recall from our discussion of attachment theory in Chapter 2 that the quality of the caregiver-child bond contributes to the developing child’s internal working model of attachment. Because each caregiver-child relationship is unique, each person’s working model—or attachment style—is also unique. These early relationships and the working models they generate become the foundation of our personality as we develop into adulthood. Attachment theory goes further by stating that the working models of attachment develop along two dimensions—anxiety and avoidance—reflecting our impressions of ourselves and our impressions of others.

When caregivers are consistent and available to meet our needs, we develop a confident, positive sense of who we are. When caregivers are inconsistent and unavailable, we feel anxious, insecure, inadequate, and unworthy of others’ care and attention. This becomes encoded as a self-relevant aspect of anxiety in our internal working model.

Our working model contains representations of others as well. When we aim to restore proximity to a caregiver and are met with love and comfort, we come to believe that others are trustworthy and that we are valued. Punishment and rejection, on the other hand, lead us to conclude that others are unreliable and are best avoided. This becomes encoded as an other-relevant aspect of avoidance in our internal working model. People who are low in anxiety and avoidance are considered to be securely attached, whereas people who understand themselves to be low in self-worth and others to be unapproachable or not trustworthy are considered to be insecurely attached.

Research has shown that people raised by emotionally sensitive and responsive parents develop attachment styles that are relatively low in anxiety and avoidance (e.g., Fraley et al., 2013; Raby et al., 2015). Once formed, these working models tend to be stable characteristics of how people approach relationships (e.g., Fraley, Vicary, Brumbaugh, & Roisman, 2011). Dozens of studies converge on the conclusion that people who are high in anxiety and avoidance struggle in their relationships more than those who are low on these dimensions, thus affecting feelings of satisfaction, connectedness, and support (Li & Chan, 2012).

Let’s look at this from a more practical point of view. Suppose your partner doesn’t respond when you want to cuddle, or doesn’t say supportive things to you when you’re feeling down. How do you make sense of this behavior? There are many ways to interpret the same event, and the various interpretations can take couples down different emotional pathways (as you’ll see in Chapter 8). Like politicians, intimate partners can “spin” a given event in a way that benefits the relationship: “She didn’t comfort me because she knew I could handle the situation myself; she really is considerate and has faith in me”—or that damages the relationship: “She didn’t comfort me because she still holds a grudge about that time I refused to help her with the chem lab assignment; she’s trying to get back at me.” A direct implication of Bowlby’s theory is that our internal working models affect how we view interpersonal events like these (Bowlby, 1980).

Interpretations made by individuals with a secure attachment style tend to minimize the impact of negative events, and interpretations made by insecure people magnify the impact of these same events. In fact, people with the most negative working models of themselves and others—fearful individuals—typically have the most pessimistic interpretations of relationship events (e.g., Collins, 1996). People who keep tight control over their emotions as a means of denying the importance of intimacy—those higher in avoidance—do in fact express less emotion in response to relationship events, and they report being less aware of their physiological cues of anger, such as a faster heart rate and muscle tension (Mikulincer, 1998).

Support for attachment theory requires evidence that people with different attachment styles behave differently in their intimate relationships, and a host of studies have demonstrated this fact. For example, children rated as having secure attachment in infancy go on to have more secure friendships at age 16; by their mid-20s, they say they experience more positive emotion in their relationships and display less negative emotion when communicating with their partners (Simpson, Collins, Tran, & Haydon, 2007; also see Karantzas, Feeney, Goncalves, & McCabe, 2013). Direct observation of couples discussing disagreements (topics that cause distress and threaten the relationship) likewise show that partners with a greater sense of security approach their relationship problems with more warmth, more compassion, and less hostility (e.g., Davila & Kashy, 2009; Dinero et al., 2008; Holland & Roisman, 2010). Secure people also report a stronger inclination to talk openly with their partner after the partner has done something potentially destructive to the relationship, and they are less likely to think about breaking up. Individuals identified as fearful show the opposite pattern, closing off contact and being more inclined to jump to conclusions about ending the relationship (Scharfe & Bartholomew, 1995).

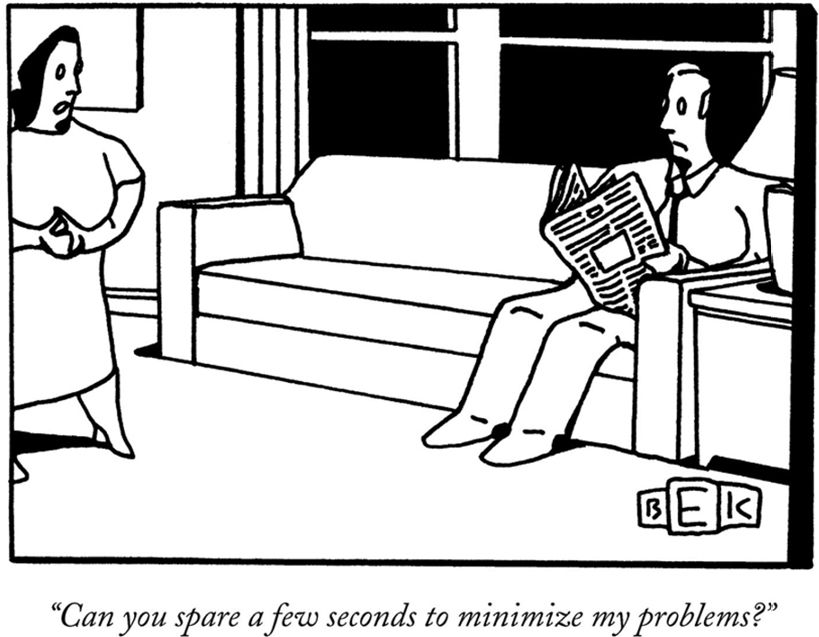

FIGURE 6.9 Insecure attachment and partner communication. This woman’s insecure attachment style causes her to use an ineffective strategy when seeking support from her partner.

Direct observation of newlywed couples discussing their relationships also demonstrates that secure partners are more likely than insecure partners to signal their needs clearly, to expect that the partner will help address these needs, and to make good use of the partner’s efforts to help (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2000) (Figure 6.9). And, when on the receiving end of these signals, secure individuals are more likely than those who are less secure to show interest, express willingness to help, and display sensitivity to the partner’s distress (Crowell et al., 2002; Kobak & Hazan, 1991; Paley, Cox, Burchinal, & Payne, 1999).

Consider the signals being exchanged in the following conversation. How do they keep both partners engaged, despite the distress Carol is experiencing?

Kim: Hey, how was your day?

Carol: Not so great. How about you?

Kim: Good enough I guess, but what’s up?

Carol: You know the story—lousy commute, Elaine needs the budget for that duplex project a week earlier than she said, and my assistant, Josh, is now telling me he might have to move to Peoria if his partner accepts a job there.

Kim: Yikes. Sounds rough—not the Peoria part, but the fact that all this is coming down at once on you. Where are you going to go with all this?

Carol: Well, Josh will at least be around to help with the budget—he has already committed to that—and I called Carter to let him know I may have to set aside the pro bono work I’m doing. So I will survive; I just have a few long nights coming up. All I know is that I’m exhausted.

Kim: I’m sure you will survive—you always do. Sorry to hear about the project with Carter—that sounded a lot more interesting than the duplex budget. Can you work from home tomorrow and avoid the commute?

Carol: You know, that’s a good idea. I’ll check with Elaine, but I’m guessing she would probably rather have me working than stuck in traffic.

Kim: Great. Maybe we can order in some dinner then.

Carol: OK, whatever. All I know is that I’m really beat.

Now compare that exchange with the following one, in which Carol is not quite as clear in expressing her needs—a tendency that characterizes people with an insecure attachment style. Notice how Kim has difficulty finding opportunities to offer any kind of support, despite her best intentions:

Kim: Hey, how was your day?

Carol: You know, same old same old.

Kim: You look a little beat.

Carol: I am, but I’m not sure your saying “you look a little beat” is going to make me feel any better.

Kim: Yeah, sorry. So anything interesting happen today?

Carol: Interesting? Yeah, my commute sucked, my boss is giving me grief about a duplex project, I had to tell Carter I have to delay a pro bono project I want to do, and Josh is probably moving to Peoria. Other than that it was a great day. And frankly I’m not sure there’s much anybody can do about it.

Kim: You mean about Josh?

Carol: No, about this crappy job and this damn commute.

Kim: Yeah, I hear you. Is there anything I can do to help?

Carol: Not unless you know how to do an Excel spreadsheet with about a zillion macros.

Kim: Sorry, I wish I did, but I can’t help you there. But let me know if there’s something I can do to help.

We can see from such examples that attachment theory does more than help explain differences in internal working models. It also provides important clues about the specific kinds of communication that can either promote or discourage successful relationships.

Differences in attachment style also appear to be magnified in times of stress. Recall that the attachment behavior system is not always operating; it is activated when a person is challenged, or when access to the caregiver is threatened. Attachment theory predicts that in times like these, people naturally signal the need for comfort and take steps to maintain or restore felt security with the attachment figure. But remember, too, that differences in attachment style should lead secure and insecure people to fulfill their needs in different ways. For example, secure individuals will assess a situation confidently and cope well, either by mobilizing others’ support or by resolving the difficulty themselves. Those prone to anxiety will compensate for their lack of self-confidence by overusing the available support, and perhaps not even feel satisfied with it. And people who are prone to avoidance will adopt a defensive position, denying the need for support and using distancing strategies to cope with their distress.

To test these ideas, social psychologist Jeffry Simpson and his colleagues assessed the attachment styles of both partners in 83 different-sex dating couples. Each woman was told: “You are going to be exposed to a situation and set of experimental procedures that arouse considerable anxiety and distress in most people” (Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992, p. 437). The researchers showed her a small, dark, equipment-filled room that looked like an isolation chamber. She was then escorted to a waiting room where her partner was seated, and their interaction was videotaped with a hidden camera for 5 minutes. The couple was then told that due to an equipment malfunction, the study could not proceed. All the couples involved were then informed about the true purpose of the study, and all of them granted permission for their videotapes to be used for the research.

Detailed coding of these videotapes showed that secure and avoidant women differed dramatically in their behavior. As secure women became more fearful of the experience, they generally turned to their partner for comfort and reassurance, confident that their concerns would be met with a compassionate response. Avoidant women, however, did not necessarily turn to their partner as their anxiety and fear increased, and they were less likely than secure women to even mention the impending stressful event to their partner. (Results were mixed for anxious women.) Figure 6.10 shows these findings.

FIGURE 6.10 Secure and avoidant women under stress. To the extent that they become more anxious and fearful while anticipating a stressful situation, secure women seek more comfort and reassurance, whereas avoidant women seek less. (Source: Adapted from Simpson et al., 1992.)

The men’s behavior was also associated with their attachment styles. Secure men gave more support and reassurance to their partner the more her anxiety and fear increased, while support and reassurance offered by avoidant men dropped off as their partner showed more distress. In other words, when confronted with exactly the same stressful situation, secure individuals reach out to their partner when needing or providing support, whereas avoidant individuals retreat—presumably because they have learned through earlier experiences with caregivers that little comfort is to be gained from others who are close to them.

The fact that our attachment styles in adulthood have deep roots in the ways our parents and other caregivers treated us as children, along with the fact that our attachment style tends to be pretty stable as we age (Fraley, Vicary, Brumbaugh, & Roisman, 2011), might leave you pessimistic about whether these feelings of insecurity can change. The famous Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) sheds some light on this issue, in a letter to his brother Theo. Here he acknowledges his profound insecurities and difficult personality to Theo—but he also provides a clue about what might help him:

I’m often terribly and cantankerously melancholic, irritable—yearning for sympathy as if with a kind of hunger and thirst—I become indifferent, sharp, and sometimes even pour oil on the flames if I don’t get sympathy. I don’t enjoy company, and dealing with people, talking to them, is often painful and difficult for me. But do you know where a great deal if not all of this comes from? Simply from nervousness—I who am terribly sensitive, both physically and morally, only really acquired it in the years when I was deeply miserable. Ask a doctor and he’ll immediately understand entirely how it couldn’t be otherwise than that nights spent on the cold street or out of doors, the anxiety about coming by bread, constant tension because I didn’t really have a job, sorrow with friends and family were at least 3/4 of the cause of some of my peculiarities of temperament—and whether the fact that I sometimes have disagreeable moods or periods of depression couldn’t be attributable to this?

But neither you nor anyone else who takes the trouble to think about it will, I hope, condemn me or find me unbearable because of that. I fight against it, but that doesn’t alter my temperament. And even if I consequently have a bad side, well damn it, I have my good side as well, and can’t they take that into consideration too? (http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let244/letter.html#translation)

What about the fight? What might be done to bring out that good side? Attachment theorists propose that insecure individuals feel reluctant to engage with their partner, hesitant to share their personal thoughts and feelings, and anxious in the belief that opening up to their partner may result in pain and rejection (e.g., Edelstein & Shaver, 2004). We see hints of all this in van Gogh’s letter, but we also see how he lashes out at others when he fails to receive the sympathy he so badly desires. Van Gogh is protecting his fragile self-image here, a task that becomes so consuming that it probably interferes with his ability to stay connected to close others, even to the point where it undermines his relationships. At the same time, insecure people really do want to feel loved and cared for within their relationships. This leads theorists to reason that if the need to protect one’s self can be reduced, then insecurities will subside, expressions of positive emotion might increase, and day-to-day exchanges with the partner might be more open and enjoyable.

A series of experiments now indicate that feelings of insecurity can be modified, and that these modifications produce real benefits for relationships. What’s interesting about this work is that a variety of strategies appear to do the trick, helping insecure individuals, or those who otherwise have low self-esteem, achieve a greater sense of personal and interpersonal security. Here are some of the simple approaches that appear to work:

1. Deepening self-affirmation. Identify some value that is important and personally meaningful to you. This value might be personal (like being loyal or honest); social (volunteering or helping neighbors); religious (believing in God or being part of a faith-based community); academic (working hard or being goal-directed); or anything else that is significant for you. Then, explain why you picked that value, and take some time to write about how it has affected your life and why it’s a key part of your self-image (Jaremka, Bunyan, Collins, & Sherman, 2011; Stinson, Logel, Shepherd, & Zanna, 2011).

2. Adopting your partner’s perspective. Imagine what a typical day is like for your partner. Pretend you are your partner, looking at the world through his or her eyes, and describe in detail what it’s like to walk through the world from his or her point of view (Peterson, Bellows, & Peterson, 2015).

3. Elaborating on a compliment. Think about a time your partner said how much he or she liked something about you, such as an important personal quality or ability, or something you did that really impressed your partner. Explain why your partner admired you. Describe in detail what it meant to you and its significance for your relationship (Marigold, Holmes, & Ross, 2007).

4. Increasing psychological and physical closeness. With your partner, work together through a series of increasingly personal questions, and discuss your responses to them (e.g., “If you were to die this evening with no opportunity to communicate with anyone, what would you most regret not having told someone? Why haven’t you told them yet?”) After answering several such questions, engage in 30 minutes of gentle stretching and yoga together (Stanton, Campbell, & Pink, 2017).

There are two important lessons from this line of research. First, simple activities can weaken the influence of insecure attachment on relationships. We may need to be reminded to implement them regularly in our daily lives, but they don’t require complex skills or professional guidance. Second, these activities—whether reaffirming deeply held values, going outside our familiar frame of reference, offering a sincere compliment, or injecting positivity and closeness into our partnership—involve steps that all of us might consider taking routinely, regardless of how secure or insecure we feel. We will have a lot more to say in Chapter 8 about how communication keeps relationships strong, but for now it is enough to conclude that regular use of small, ordinary acts can modify even stable and ingrained self-perceptions.