I don’t care too much for money, money can’t buy me love.”

I don’t care too much for money, money can’t buy me love.”

—John Lennon and Paul McCartney (1964)

I don’t care too much for money, money can’t buy me love.”

I don’t care too much for money, money can’t buy me love.”

—John Lennon and Paul McCartney (1964)

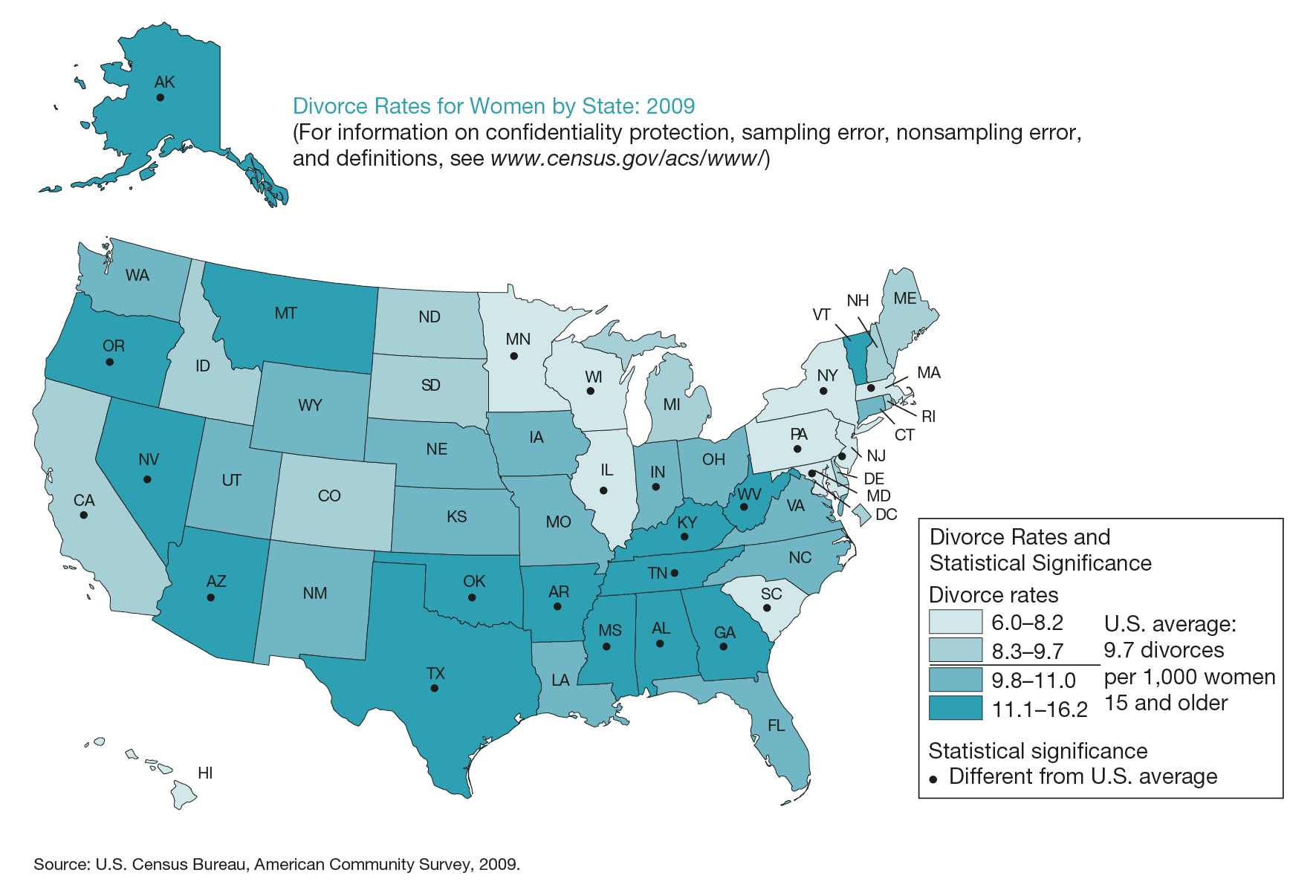

Having money cannot guarantee you will find someone to accept you and support you throughout an enduring intimate relationship. But once you’ve found someone to love, whether or not you have enough money makes a huge difference. How much of a difference was revealed in 2009, when newspapers around the United States reported on census data collected the previous year indicating that Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Tennessee had the highest divorce rates in the country, around 50% higher than the national average (Figure 13.11). Many people initially found this surprising because these four states constitute the heart of the Bible Belt, a region of conservative values and strong connections to religious organizations, which many predicted would have led to lower divorce rates, not higher ones.

FIGURE 13.11 Divorce in the Bible Belt. When census data revealed that Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Tennessee had the highest divorce rates in the U.S., the governors of those states struggled to respond.

Initial efforts to explain the puzzling finding focused on expectations and education. For example, Jerry Regier, Oklahoma’s Secretary of Health and Human Services at the time, suggested to the press that young people do not have a realistic view of marriage. The Governor of Arkansas declared a “marital emergency” and promised support for educational programs designed to lower his state’s divorce rate. Relationship education began to be written into high school curricula, with required classes teaching communication skills and relationship values (Hawkins & Ooms, 2012). The idea was that high divorce rates result from a general misunderstanding of the challenges of marriage. Relationship education to correct that misunderstanding should, therefore, lower divorce rates and presumably lead to happier marriages.

The problem with this line of reasoning is that it’s hard to explain why couples in the Bible Belt states would misunderstand marriage more than couples elsewhere in the country. Were there any other possible reasons? In fact, the same data for state-by-state differences in divorce rates also pointed out other ways in which these four states were distinct. According to the National Center for Health Statistics (2003), these states ranked near the bottom of the 50 states in terms of employment rate, annual pay, household income, and health insurance coverage. At the same time, they had among the highest rates of murder, infant mortality, and poverty in the nation. Therefore, while it’s possible couples in Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Tennessee misunderstood the challenges of marriage, life in general was definitely more challenging in those states, and nearly two decades later, little has changed (Semega, Fontenot, Kollar, & U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The observation that divorce rates are higher where the overall quality of life is poor suggests an alternative explanation: Marriages that might survive and even thrive elsewhere may struggle in the face of unstable working conditions, neighborhoods beset by crime, poor education, and low wages.

Socioeconomic status (SES) is an indicator of all the ways individuals differ in their ranking within a social structure. In the United States, SES is often measured as a composite variable that takes into account a person’s household income, level of education, and occupation. Most research on the links between SES and intimate relationships has focused on marriage, and the evidence that SES affects the health of relationships is extensive. Here are some examples:

FIGURE 13.12 Marriage in poor neighborhoods. An analysis of 1995 census data revealed that, compared to women in affluent neighborhoods, women in poor neighborhoods were more likely to divorce and to divorce earlier. (Adapted from Bramlett & Mosher, 2002.)

Some people believe that high rates of divorce reflect a moral downturn, or a lack of dedication to the institution of marriage. David Popenoe, professor of sociology and head of the National Marriage Project at Rutgers University, testified in 2001 before a subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives as part of a hearing on welfare and marriage issues. He suggested that the breakdown of marriage was at its heart a problem of declining values. “Our national goal,” he told Congress, “should be no less than to rebuild a marriage culture” (Popenoe, 2001). Other notable scholars and social leaders have echoed this call, suggesting that high rates of out-of-wedlock pregnancy and increasing rates of divorce can directly be attributed to society’s failure to appreciate the value of stable, healthy marriages, and its failure to teach this value to each new generation (Waite & Gallagher, 2000; Wilson, 2002). These messages all suggest that low-income communities, where rates of divorce are highest, are especially lacking in these values.

Is there any evidence that attitudes toward marriage are in fact declining? On the contrary, surveys throughout the U.S. consistently reveal that, in the country as a whole, people’s attitudes about marriage have remained highly positive over the last several decades (Axinn & Thornton, 1992; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Young adults, ages 20–24, continue to value marriage very highly. National survey data show that 83% of men and women in this age range believe it is important or very important to be married some day (Scott, Schelar, Manlove, & Cui, 2009). And about 90% of young adults in the same study expected they would be married by the time they reach age 40. Nearly 80% of gays and lesbians want to be married as well (Egan & Sherrill, 2005), and since 2015, when the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples have the same right to marry as anyone else, they can be (Figure 13.13).

FIGURE 13.13 Valuing marriage. For decades, the desire to marry has been strong and consistent across a wide range of the U.S. population.

Extending this work, researchers directly compared responses from more and less affluent respondents in a telephone survey of 6,012 people living in Florida, Texas, California, and New York (Trail & Karney, 2012). These analyses paint a similar picture, suggesting that on some attitude scales, poorer men and women report even more positive attitudes toward the institution of marriage, and even less approval of divorce, than wealthier men and women. For example, the wealthiest respondents in this study were significantly more likely than the poorest respondents to agree that divorce can be a reasonable solution to an unhappy marriage. In contrast, the poorest respondents were more likely to agree that for the sake of children, parents should remain married even if their relationship has declined. Another research team had examined responses to the same sorts of items from women who were receiving public assistance (Mauldon, London, Fein, & Bliss, 2002). These women reported high levels of agreement with statements expressing positive attitudes toward marriage (e.g., “People who want children ought to marry”) and a strong desire to marry themselves.

Throughout the United States, on average, and within low-income populations in particular, there is no evidence that marriage has lost its value. In fact, as sociologist and professor of public policy Andrew Cherlin (2005) has observed, marriage appears to have developed into a symbol of status and prestige, and this is even truer for low-income populations than for more affluent groups.

If people from all walks of life and all socioeconomic levels actually agree about the value of marriage, where does the sense of a declining appreciation for marriage come from? What appears to have changed is not the value of marriage but rather the tolerance and acceptance of family forms other than marriage (e.g., cohabitation, divorce, premarital pregnancy). For example, when researchers examined four decades of survey data from 1960 to 2000, they noticed that while attitudes toward marriage did not change much during that time, attitudes toward divorce, premarital sex, unmarried cohabitation, remaining single, and choosing to be childless all became more acceptable (Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001).

When researchers have directly asked poor couples about the forces that get in the way of maintaining their relationships, their answers focus not on values and attitudes but on the specific challenges of being poor (Trail & Karney, 2012). Low-income relationships form and develop in what may be a fundamentally different context than the context for those who are more affluent, and the differences extend far beyond income. Being poor is accompanied by a host of other challenges that have a negative impact on committed relationships.

For example, members of low-income communities are far more likely than those in wealthier communities to have serious health problems (e.g., Gallo & Matthews, 2003). Because income is strongly associated with level of education, partners in poor couples generally have less formal education than more affluent partners (Fein, 2004). In terms of personal history, they are more likely to have been raised in a single-parent home (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994) and to have been exposed to physical and sexual abuse during childhood (Cherlin, Burton, Hurt, & Purvin, 2004). Perhaps as a consequence, rates of psychopathology, criminal behavior, and substance abuse are all higher in low-income communities (Costello, Compton, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Cutrona et al., 2005). For these reasons, people raised in poor areas are more likely to have personal challenges quite apart from trying to maintain an intimate relationship with another person. They start out at a significant disadvantage.

Throughout this chapter, we have been discussing how couples are affected by the context of their relationship. For low-income couples, the context contains more demands than resources, starting with financial strain. In addition, poor neighborhoods generally have more social disorder (e.g., crime, drug use, delinquency), and the homes of low-income families are likely to be more crowded, noisier, and in worse condition (Evans, 2004). There is some evidence that low-income couples may benefit from extended families and well-developed social and religious networks (e.g., Anderson, 1999; Henly, Danziger, & Offer, 2005; Moore, 2003). However, these networks can be a further drain on couples as well (Cattell, 2001). For example, the working poor spend more time caring for disabled and elderly family members than do more affluent groups (Heymann, Boynton-Jarrett, Carter, Bond, & Galinsky, 2002). Poor working mothers are also twice as likely to have a child with a chronic health condition (Heymann & Earle, 1999). Therefore, low-income couples have a hard time simply surviving and caring for those who depend on them, all within a context that does not provide much support.

Time is another resource that is scarce for poor couples. Because of demands outside the home, they usually have less time to spend together. Sociologist Harriet Presser and her colleagues have documented work patterns among poor working families (Presser, 1995; Presser & Cain, 1983). In several studies they found that members of low-income couples are more likely than middle- and high-income couples to be forced to work nonstandard hours. During the evenings and weekends, when they could be communicating, being intimate, and sharing leisure time, low-income couples are more likely to be at their jobs.

Even when they do have time outside of work, they can’t really choose how to spend that time. Analyses by the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth have shown that working poor families are less likely to have paid sick leave, vacation leave, or flexible work hours (Heymann, 2000). With less control over when their free time will be, it’s harder for poorer couples to set aside time for taking care of their children, attending school meetings, or catching up with each other’s lives.

Stressful contexts like these affect the emotional well-being of couples. When married women with children work nights, their chance of divorce is three times higher than women who work the same number of hours during the day (Presser, 2000). When married men with children work nights, their chance of divorce is six times higher. These findings make sense when we stop to consider what makes marriage and intimate relationships fulfilling. All couples need time to interact and be intimate. Poor couples, who are more likely to be working double-shifts just to keep food on the table, don’t generally have this kind of time. When they do have time to talk, they have more difficult things to discuss. Low-income couples filing for divorce cite communication issues like everyone else (Amato & Previti, 2003), but it may not be communication itself that is at the heart of their problems.

What kinds of programs might be most effective in helping families and couples in poor communities? There are no simple answers, but efforts to improve the lives of low-income couples are likely to be most successful when they acknowledge the real challenges that these couples face. This is not always easy to do. Earlier, we described how the governors of four states reacted with shock when they learned their states had the highest divorce rates in the country. In response, the federal government initiated programs designed to promote the value of healthy relationships and teach poor couples effective communication skills (Dion, 2005). Although hundreds of millions of dollars have now been spent on such programs, the results of two national evaluations indicate little or no success in making low-income relationships more stable or more satisfying (Hsueh et al., 2012; Wood, McConnell, Moore, Clarkwest, & Hsueh, 2012).

If the success of a relationship depends on the general quality of a couple’s life, then programs that improve the lives of low-income individuals are likely to benefit their relationships as well. An example from Norway makes this point. In 1999, families who chose not to use government-run daycare services, which essentially paid couples to stay home with their young children, were offered financial aid. The policy did not mention marriage, nor did it target marriages directly. But divorce rates in Norway before and after the policy took effect dropped significantly among couples who accepted the aid (Hardoy & Schøne, 2008). Simply allowing families more time to spend together apparently strengthened their marriages.

Many other efforts that don’t immediately look like relationship enhancement programs have also had positive effects in disadvantaged populations. A program that provided healthy drinking water to communities in arid regions of Eastern Kenya ended up improving family relationships there (Zolnikov & Salafia, 2016). Anti-poverty programs that offer job training or cash assistance tend to lower divorce rates as well (Lavner, Karney, & Bradbury, 2015). Programs that simply make life easier may turn out to be just as effective at helping poor couples as those that address relationship problems directly (Johnson, 2012).