- Even very young children are acutely sensitive to the quality of the interactions among the adults around them, particularly their parents.

- Interactions among adults provide models of intimacy that children draw on in their own relationships as young adults.

- Repeated exposures to adult conflicts predict angry, aggressive behavior in children.

Born into Intimacy: How Adult Relationships Influence Children

Although we have little opportunity to express intimacy as infants, we are surrounded by intimate relationships from our earliest moments. The most significant of these is the connection we have with our primary caregivers, usually our parents. The man who grew up to become Harry Houdini was lucky in this regard, for he was born to parents who were devoted to each other. In Budapest, Hungary, his father, Mayer Samuel Weisz, lived in a Jewish community where arranged marriages were common, so Houdini’s parents might not have shared an emotional bond at all. But Mayer escaped this fate when a close friend, a shy type, asked him to deliver a message of love to a young woman named Cecilia Steiner, whose family Mayer knew. In delivering the message, Mayer realized he had fallen in love with the girl himself, and when he learned his feelings were returned, the couple were married.

The marriage lasted 28 years, until Mayer’s death in 1891. Their lives together were not easy. In addition to a son from his first marriage, Mayer and Cecilia eventually had six children (Figure 14.2). Seeking opportunity in America, Mayer left Cecilia and the children alone in Hungary for nearly 2 years until he could bring them to join him in Appleton, Wisconsin, where he had established himself as a rabbi. In later years, Houdini would tell of his 12th birthday, when his ailing father made him promise that, after he died, Harry would make sure his mother was well cared for. Mayer’s concern for his wife’s well-being set an example Houdini would never forget.

FIGURE 14.2 Houdini’s earliest social ties. In this photo, Houdini is in the middle, surrounded by four brothers, all of whom interacted regularly throughout their lives. How do you think the constant activity of a busy household during his earliest years affected his capacity to socialize effectively with others?

Do Children Understand Adult Interactions?

How might the strong relationship between his parents have affected the course of Houdini’s life? As recently as the 1970s, this question sparked controversy among scholars. On the one hand, therapists who worked with families were convinced that behavior problems in children have their roots in the relationship between the parents (e.g., Framo, 1975). On the other hand, some researchers suggested that the emotions expressed within adult couples were simply too complex for young children to understand (e.g., Herzog & Sudia, 1968).

In recent decades, this debate has been settled. Numerous studies have confirmed that even young children are extremely sensitive to the quality of the interactions between the adults around them. Children whose parents have relationship conflicts are more likely to experience depression, behavior problems in school, and problems in their own peer relationships, compared to children whose parents are generally loving toward each other (Emery, 1982; Grych & Fincham, 1990). These effects have been demonstrated across cultures and around the world (Cummings, Wilson, & Shamir, 2005; Shamir, Cummings, Davies, & Goeke-Morey, 2005). It is not only outright hostility that affects children; in 6-year-olds, signs that parents are withdrawn from each other also predict distress (Davies, Sturge-Apple, Winter, Cummings, & Farrell, 2006). In all these studies, the parents’ relationship affects their children, even when the warmth each parent directly expresses to the child is taken into account.

How sophisticated an observer of adult interactions can a child be? It’s natural to feel distress when two adults are shouting at each other or are withdrawn from each other. But it’s difficult to recognize the subtleties of a real adult conflict, where the simple phrase “I’m fine” can be loaded with multiple meanings, depending on how it is expressed. In an extensive program of research exploring this question, developmental psychologist Mark Cummings and his colleagues asked children as young as 4 years old to watch videotapes of adults discussing typical relationship problems. The adults were not the children’s parents; they were actors performing scripts written by the researchers. Controlling exactly what the children observed, the researchers manipulated aspects of the adult interactions to figure out whether young children can distinguish subtle shades of meaning. In one study, children of various ages watched videotapes of adult couples having an argument; then the researchers manipulated whether the argument was settled or whether it ended without a resolution (Cummings, Vogel, Cummings, & El-Sheikh, 1989). Regardless of their age, children were sensitive not only to the presence of conflict but also to how it ended. A pleasant resolution reduced the distress of being exposed to the disagreement itself, whereas an angry or a withdrawn ending increased the negative effects on the children.

The Impact of Adult Conflict on Children

Parents naturally dominate their young child’s social world, so it makes sense that a child’s sensitivity to the emotional environment between the parents develops from a very early age. Being completely dependent on adults, a toddler’s survival requires knowing when those adults are in a good mood and willing to provide care, or a bad mood that might distract them from providing care. But there are also less obvious ways that adult relationships affect children.

Imagine you’re a small child listening to a heated conversation between your parents. The two adults are arguing with each other, not with you, and may even be in another room, unaware that you can hear them. But you do hear them. What does it mean for you? Observations of adult relationships provide children with models to follow in their own relationships as young adults. One study, for example, videotaped couples discussing areas of conflict in their marriage, and then 3 years later had their teenaged children rate the level of anger and aggressive behavior in their own romantic relationships (Stocker & Richmond, 2007). The more angry their parents were in the taped discussions, the more the teenagers described their own relationships as being hostile and aggressive.

In a rare experimental study demonstrating these effects, researchers invited three groups of 2-year-old children to play in a room furnished to look like a living room, complete with kitchenette (Cummings, Iannotti, & Zahn-Waxler, 1985). While the children were playing, a pair of research assistants entered the room three times to distribute juice and clean up. For the first group, the two assistants were nice to each other when they first visited the room, but on their second visit they had an angry (and thoroughly scripted) argument over whose turn it was to do the dishes. On their third visit, they appeared to reconcile and were nice again. The second group of children had the same experience, and then also returned to the research room a second time, where pretty much the same events occurred with a different pair of assistants. For the third group of children, the two assistants were nice to each other whenever they entered the room.

All three groups were videotaped, and researchers examined the tapes closely to address two questions. First, how did exposure to adult conflict affect the way the toddlers behaved? It is not surprising that the children who witnessed the two adults quarreling were more likely to show obvious signs of distress, like covering their ears with their hands or verbally scolding the arguing adults (“Bad ladies!”). More significantly, the children exposed to the angry adults behaved more aggressively toward other children after the adults had left the room. Although the adult conversation was in the background and not directed toward the children in any way, the exposed children were nevertheless more likely to express anger, grab toys from other children, and even physically attack another child after the adults had left the room. These behaviors declined dramatically after the adults returned for their final friendly interaction.

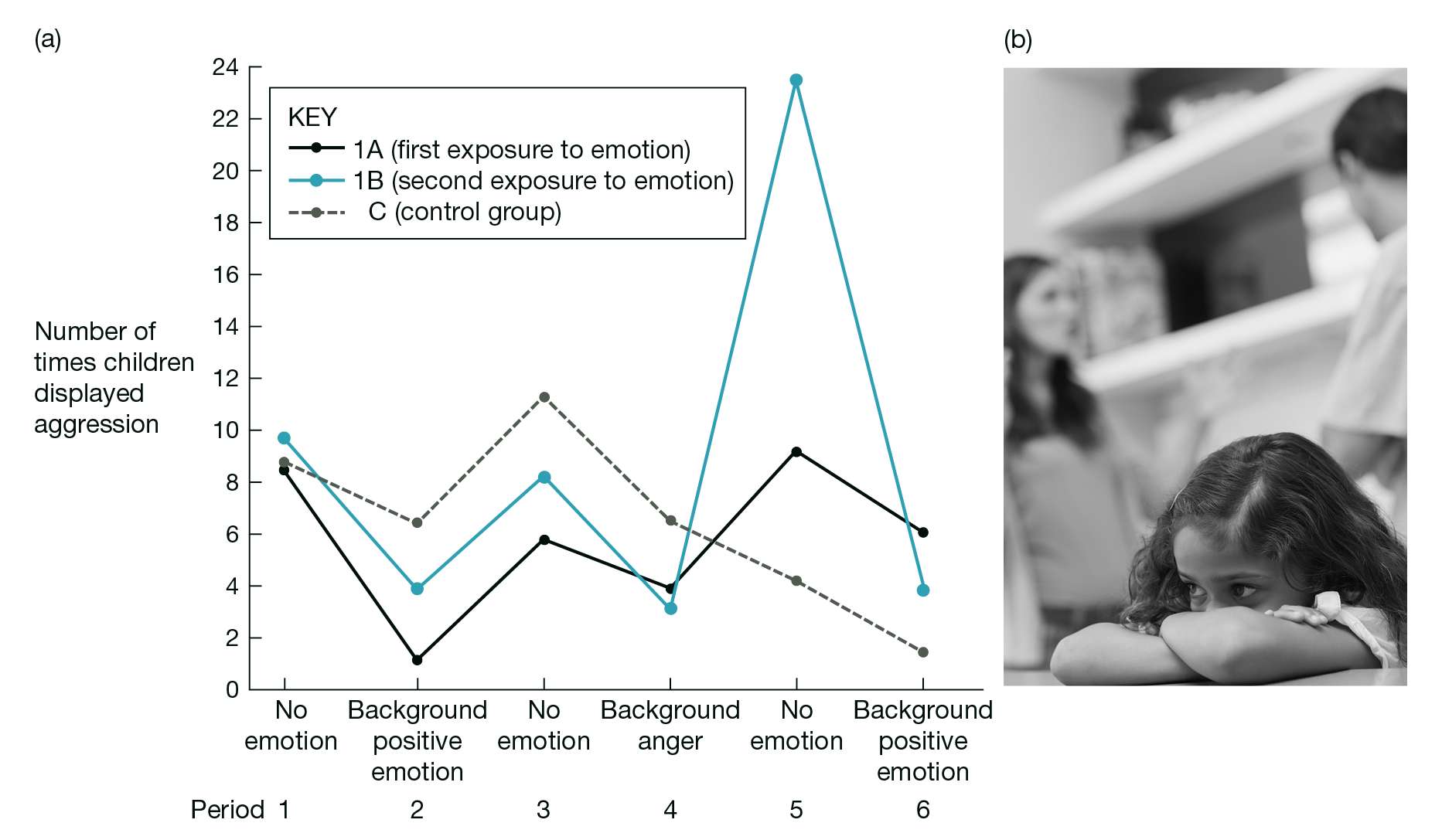

The second question for the researchers was whether the effects of adult conflict on children’s behaviors changed with repeated exposures. Do children exhibit desensitization, becoming accustomed to the sound of adults arguing in the background? Or do they demonstrate sensitization, becoming increasingly reactive the more conflict they witness? As Figure 14.3 shows, this study found strong evidence for sensitization. Although exposure to adult conflict predicted more aggressive behavior in all the experimental groups, the children who watched the angry interaction twice were far more unruly than any others.

FIGURE 14.3 Sensitization or desensitization? (a) In this study, children who were exposed to adults arguing were more aggressive themselves immediately afterward, compared to a control group that was not exposed. Children who watched a second time were even more aggressive, demonstrating sensitization. (Source: Cummings, Iannotti, & Zahn-Waxler, 1985.) (b) Even very young children are acutely sensitive to the quality of the relationships between adults around them.

If these researchers were able to observe such dramatic effects in a relatively impersonal research setting, we might expect that the effects of adult conflict in children’s real lives are far greater. In this study, the adults were strangers to the children, but in real life, the arguing adults are often parents and others on whom the child depends. In this study, the argument was emotional but not violent, and the topic was not directly related to the children. Imagine how much more distressing abuse or violence must be, or an argument about issues that relate directly to the child (such as parenting). Finally, in this study, children were significantly more sensitive to the adult conflict after being exposed only twice, but in real life children are often exposed to conflict repeatedly over months or years. Other studies have clearly shown that repeated exposures to adult conflict do have long-term effects on the emotional security of children (Davies & Cummings, 1998).

MAIN POINTS

Glossary

- desensitization

Reacting less strongly to a particular stimulus the more one is exposed to it. See also sensitization.

- sensitization

Becoming increasingly reactive to a stimulus after repeated exposures to it. See also desensitization.