IN OCTOBER 1873, John William Laing arrived in Bombay to spend five months on a sightseeing tour of India. He stayed with friends in Malabar Hill, an exclusive area of Bombay, and in his diary he wrote down the menu for the dinner he was served on 28 October:

Curry did not feature, neither in the form of the Mughlai food familiar to the East India Company merchants, nor as bowls of Anglo-Indian curry and rice.

Although he noted down what he ate, John Laing saw no reason to comment on the food or the manner in which it was served. By the 1870s ‘a person fresh from England’ found nothing unusual in Anglo-Indian dining habits. Just as it was in Britain, the dinner was served at seven or eight in the evening; the men and women wore evening dress; the food was served on the best Wedgwood china, imported from Staffordshire, and eaten with elegant silverware; and the champagne or claret was drunk from fine crystal glasses. One or two attentive servants changed the dishes and removed the plates as each course was brought to the table. Despite the alien surroundings, the late-nineteenth-century Anglo-Indian dinner party faithfully reproduced the food and table etiquette of the urban bourgeoisie in Britain.

All the hallmarks of the burra khana had been eradicated. The crowds of servants, which had surprised Fanny Parks in the 1820s, had been greatly reduced. In the 1830s Anglo-Indians had begun printing ‘No hookahs’ in the corner of their dinner invitations, and by the 1870s the pipes no longer bubbled quietly behind every chair. The airy white linen the gentlemen used to wear had been exchanged for respectable black evening dress. As early as 1838, a visitor to India was pleased to discover that ‘French cookery is generally patronised, and the beef and mutton oppressions of ten years since are exploded’. The huge saddles of mutton, the hams and the turkeys had been replaced with ‘made’ dishes, served in separate courses. Moreover, curry and rice had been dropped from the menu. A review of a cookery book in a Calcutta periodical in 1879 noted with satisfaction that ‘the molten curries and florid oriental compositions of the olden time . . . have been gradually banished from our dinner tables’.2 As Victorian Britain was enthusiastically embracing the idea of empire, and curry was becoming a favoured dish among the middle classes, Anglo-Indians were busily eradicating as many traces of India as possible from their culture.

This change in dining habits demonstrated a desire to keep up with fashions back at home. In the early nineteenth century it had been commonplace for visitors to India to refer to the uncouth nature of Anglo-Indian society. One handbook snootily asserted that to anyone who had ‘been accustomed to move in the good circles of England, the contrast must be striking, and we apprehend, unfavourable to the Anglo-Indian community’.3 The author went on to state that in India ‘in little appertaining to the table . . . is the comme il faut thoroughly understood’.4 But Anglo-India was changing. More women were beginning to arrive in the colony, and the introduction of steamships and an overland route to India via Egypt improved communications with Britain. Gradually, the rough and ready nabobs began to lose ground to a new group of Anglo-Indians – the sahibs and memsahibs – who resented the implication that they were nothing more than nouveau-riche parochials and concentrated their efforts on maintaining civilised standards, even in the remote wilds of India. Advocates of the new utilitarian and evangelical ideologies were also beginning to arrive. They argued that British officials were not in India to run the country for a money-grubbing trading company but to bring to its backward and impoverished people the benefits of civilisation. The men to carry out this programme needed to be fine upstanding representatives of Englishness. Nabobs who smoked the hookah, lazed about in cool white linen, and kept an Indian mistress in the purdah quarters of their bungalow began to give way to black-coated bureaucrats. After the abolition of the East India Company in 1858, the racial theories of the latter half of the century emphasised the need for both the civil servant and the military officer to demonstrate the superiority of the British race. The gentlemanly product of the public schools was promoted as the ideal colonial ruler. These were young men who were supposedly self-reliant, decisive, independent and athletic, with a strong sense of their own authority, and, most importantly, they were thought to be capable of upholding British prestige at all times.

As part of the imperial project to maintain prestige, curry and rice were demoted: ‘A well considered curry, or mulligatawni – capital things in their way, – [were] still frequently given at breakfast or luncheon’, and curry was the main dish out in camp, on long journeys, at dak bungalows, and in a variety of informal settings. But to serve a curry for the evening meal was now frowned upon. In Victorian Britain, dinner was the central meal of the day and it was therefore singled out by the Anglo-Indians as the most important meal, when they concentrated on demonstrating their Britishness. Many complained that it was absurd to don black evening dress in the stifling Indian heat and sit down to eat roast beef and suet puddings but this was precisely what the British did. Cookery books were published which instructed the memsahib ‘how best to produce, under the special circumstances of the country, the dishes approved by the taste of polite society at home’.5 The recipes inside Wyvern’s Indian Cookery Book and The Wife’s Cookery Book being Recipes and Hints on Indian Cookery were not for the curries and Indian pilaus which one might have expected, but for cheese crumb croquettes, thick kidney soup, sole au gratin, stewed beef with oysters, toad in the hole, Yorkshire pudding, and white sauce.6 This was a selection of dishes which could have come from Mrs Beeton. What the memsahibs tried to achieve was the same plain, wholesome British home cooking, mixed with the occasional dash of French sophistication, which was current in Victorian Britain. The results, however, tended to be disappointing. On the whole Anglo-Indian British food was ‘monotonous, tasteless, and not nourishing’. One missionary who lived in India in the 1930s referred to it as ‘pseudo-European’.7 What the memsahibs created was a second branch of Anglo-Indian cookery. The pseudo-Indian curries, mulligatawny soup and kedgeree of the first half of the nineteenth century were now joined by an array of slightly orientalised British dishes.

A variety of circumstances conspired against the Anglo-Indians’ attempts to produce palatable approximations of British food in India. Firstly, the Muslim cooks the British usually employed were hampered by their lack of personal experience of the food they were trying to produce. The Indian cook could not hold up the taste of his salmon mayonnaise or plum pudding against the memory of a meal eaten in Britain. This, combined with the fact that Indian and British cookery were very different, meant that it was extremely difficult for them to form an accurate concept of what they were aiming for. The result was a long line of cooks trained in a culinary style of which they had no personal understanding, each one passing down his own eccentric and peculiar interpretations of British dishes, until they eventually became engrained in the Indian understanding of British cookery. This could lead to some truly awful misunderstandings. One army officer was eventually forced to sack his cook because he insisted on indiscriminately adding vanilla to every single dish he cooked whether it was beef olives, grilled fish, or bread and butter pudding.8 Divorced from culinary developments in Britain, Anglo-Indian cookery inevitably developed into an independent branch of cuisine.

A variety of British dishes underwent a process of orientalisation. Meat casseroles, usually made with carrots and celery in a wine-based sauce, thickened with flour, were livened up with Indian spice mixtures (masalas). The results were neither curries nor casseroles but something in between. Anglo-Indian cookery used the cuts of meat familiar to the British, and the same methods of roasting and grilling, but the treatment given to the meat was often distinctively Indian. Rather than stuffing chicken with breadcrumbs and herbs, the Anglo-Indians’ cooks smothered the meat in coriander, cumin and pepper and created masala roasts. In Britain, cooks would thriftily use up leftover cold meat by mincing it and then covering it in mashed potatoes. These ‘chops’ or ‘cutlets’ were then dipped in egg and coated in breadcrumbs and fried. In India, the memsahibs taught their kitchen staff this method for using up leftovers, but the cooks added their own distinctive masala mixtures to the mince or mashed potato to produce spicy Anglo-Indian ‘cutlets’.

Materials. One lb. of cold Beef or mutton minced fine and pounded on a board with the ‘Koitha’ [a long knife used with a wooden board]. Moisten the mince with a little gravy or broth, add a minced onion, with its juice pressed out, some pounded spice and pepper, a few leaves of chopped mint, a green chilly, and a slice of bread soaked in water and well squeezed. Salt to taste. Put the meat pulp and the other ingredients together, mix well with a raw egg, form the mixture into balls, put a layer of bread crumbs on the board and lay on it a ball of meat, form it into the shape of a cutlet, sprinkle a thick layer of crumbs over, and fry the cutlets brown in ghee or dripping.9

The Indianisation of French cuisine began with the names of the dishes which were frequently ‘strangely transmogrified’. George Cunningham, an Indian civil servant in the 1920s, sent home a menu for

Beef Filit Bianis

Roast Fowl

Girring Piece Souply

Putindiala Jumban

Dupundiala Promison

What do you make of the enclosed menu, the joint result of one of Mugh cook’s kitchen French and a Hindu Babu? The beef fillet bearnaise and the green pea soufflé are fairly easy, but ‘pouding a la jambou’ (it was made to look like ham) is not so obvious, and the ‘Permesan’ savoury beats me. It was little rounds of cheese pastry with cheesy eggs on top but I can’t think what word he is driving at.10

The results were not always unpleasing. Bland, cream-based sauces were given some bite with a dash of Worcestershire sauce or a pinch of cayenne pepper. But the Indianisation of French cuisine did produce some spectacularly unappetising concoctions. Lady Minto, the wife of the viceroy (1905–10), dutifully copied into her cookery notebook a recipe for Soufflé de Volaille Indiénne which required a mousse of chicken and curry sauce to be poured into a soufflé case. Once set, a circle of the mousse was removed and the hole filled with mulligatawny jelly mixed with rounds of chicken and tongue. This was served with a salad of rice and tomatoes mixed with mayonnaise and curry.11

Matters were not helped by the fact that many memsahibs had no idea how to cook themselves. They arrived in India with a clear idea of how British food should taste, but no real notion of how this was achieved. Many had left home when they were very young and had no experience of running a household. The problem of inexperience was made worse by the fact that their knowledge of Indian languages was often limited to a few words spoken in the imperative. Some cookbooks tried to solve this problem by printing the recipes in Indian languages. This was all very well if one was lucky enough to employ a literate cook but even then things could go awry. What to Tell the Cook, or the Native Cook’s Assistant, which printed the names of the recipes in English and the rest in Tamil, cheerfully asserted that it would ‘save the house-keeper the trouble of describing the modus-operandi’. But the second edition followed the suggestions of several readers and printed the English text on the opposite page.12 Obviously some housekeepers wished to try and locate the reason for the cook’s failed attempts at buttered crab and Snowden pudding.

Indian conditions were unfavourable to British ways of preparing meat. In Britain, carcasses were normally hung for a few days after the animals were slaughtered. In the Indian climate this was out of the question, and the flesh had to be cooked the same day that it was killed. Roasting, grilling or boiling did not help to make such tough meat any more palatable. Indian methods of stewing chicken in curries, or slowly tenderising mutton in dum pukht dishes, or mincing and grinding beef or lamb into a fine paste before roasting it, were much more suitable for dealing with freshly killed meat. Some memsahibs acknowledged defeat and ‘gave up ordering roast chicken. The too recently killed victim tasted better if gently stewed or made into a curry.’13

Indian kitchens were not really set up for the preparation of British dishes. The kitchen equipment was usually a grinding stone, a few large pots, a spit, a kettle and a simple wood-fired oven. Even if the cook was provided with a table he would usually ignore it and conduct most of his tasks sitting or crouching on the floor. In the early nineteenth century, Thomas Williamson warned that only those with strong stomachs should investigate the cook room. The sight of the cook basting the chicken with a bunch of its own feathers was likely to turn ‘delicate stomachs’, and to catch the cook in the act of using the same implement to butter toast, was quite off-putting. Similar warnings were still being issued in the 1880s and one handbook advised ‘either . . . visit the kitchen daily, and see that it has been properly cleaned out, or never go to it at all’.14 Many Anglo-Indians adopted the latter piece of advice and cheerfully followed Williamson’s line of thought that if ‘the dinner, when brought to the table, looks well, and tastes well: appetite . . . prevents the imagination from travelling back to the kitchen’.15 Sometimes this suppression of the imagination was exercised even though the food was demonstrably unpleasant. One memsahib, very new to India, was horrified to discover that her breakfast of semolina porridge was full ‘of little cooked worms. It could almost be called worm porridge.’ In a small, frightened voice she commented on the worms. This brought the spoons of her breakfast companions to a halt, but she had the decided feeling that her ‘host felt he had been most unreasonably deprived of his breakfast’. After some time in India she gave up trying to eradicate worms from flour and came to the conclusion that it is ‘Better to come to reasonable terms with Nature in the East’.16 For the more concerned memsahib, life turned into a constant struggle with the servants. She would spend her days doling out the supplies, watching to see that the milk and water were properly boiled, picking through the flour for worms, and worrying that the moment her back was turned the cook would revert to unhygienic habits.

India constantly conspired against the stuffy attempts of the British to impose a veneer of grandeur on their lives. In any Anglo-Indian house all one had to do to destroy the illusion of effortless elegance, so carefully created in the dining room, was to step on to the back verandah. Here one would discover a host of Indian servants: one pulling the punkah, some sleeping, others washing up or boiling a kettle for tea.17 Indeed, it was the very servants who were essential to constructing this atmosphere of grandeur who so often introduced a false note or an atmosphere of tension. Bearers were in the habit of burping in the presence of their masters, butlers would demonstrate dissatisfaction by ‘snuffling . . . loudly and offensively’ while serving dinner.18 Even the respectful blank stare which many Indian servants adopted had the uneasy effect of making one feel negated. Besides, there was always the sneaking feeling that the smooth show of subservience concealed an attitude of contempt. Of course, many Anglo-Indians felt great affection for their servants, but even then this did not always mean that they were particularly competent. One family was blessed with ‘a disarmingly gentle’ ‘Cookie’ who would sit rocking their dog in his arms whenever it was ill. Naturally this meant that there was no supper, but this did not matter as much as it might have done, as he was an ‘abominable’ cook.19

The British in India never really took to Indian fruit and vegetables. ‘I have often wished for a few good apples and pears in preference to all the different kinds of fruits that Bengal produces,’ wrote a homesick accountant from Calcutta in 1783.20 The Anglo-Indians thought that aubergines and okra tasted slimy and unpleasant. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier described how the East India merchants at all the seventeenth-century European factories planted extensive kitchen gardens with vegetables familiar to them from home, such as ‘salads of several kinds, cabbages, asparagus, peas and principally beans, the seed of which comes from Japan’.21 The Europeans also brought with them newly discovered American vegetables, such as potatoes and tomatoes. It is hard now to imagine Indian food without these European and American vegetables, but in fact it took a long time for many of them to be integrated into Indian cookery.

How the potato came to India is unclear. The Portuguese or the Dutch may have brought the first specimens to the subcontinent, but they were unusual enough in 1780 for the Governor-General Warren Hastings to invite his fellow council members to join him for dinner when he was given a basket of potatoes by the Dutch. Even in Britain at the time potatoes were a novelty, grown by wealthy farmers and professionals in their kitchen gardens, but not yet a part of the staple diet. One of the first things Lord Amherst did as Governor-General in 1823 was to order that potatoes should be planted in the park at Barrackpore.22 The Bengalis took to potatoes with enthusiasm. Their starchy softness contrasted perfectly with the sharp flavours of mustard seeds and cumin which were common in Bengali cookery. By the 1860s they had become an essential ingredient in the region’s diet. From Bengal, potatoes spread inland. An army wife travelling through northern India between 1804 and 1814 reported that ‘the natives are all fond of it, and eat it without scruple’.23 In the south, potatoes took longer to become popular and James Kirkpatrick, resident at the Indian court of Hyderabad, missed them so much that he had a supply of them brought from Bombay with an armed guard through the wars raging in the Deccan. Even today, potatoes are regarded by some Indians with residual suspicion as a new and strange foodstuff, uncategorised by Ayurvedic medicine. The botanist George Watt noticed that the Indians thought they ‘cause[d] indigestion and flatulence’, and orthodox Jains refuse potatoes on the grounds that as root vegetables they possess the ability to generate life and therefore cannot be consumed.24

The Bengali names of many European vegetables indicate that the Bengalis were introduced to them by the British. Tomatoes are referred to as biliti begun or English aubergine. It took longer for tomatoes to become popular, but George Watt noticed in 1880 that although they were still ‘chiefly cultivated for the European population . . . Bengalis and Burmans use [them] in their sour curries’.25 Nineteenth-century tomatoes were sourer than the ones we are accustomed to today and they were particularly well suited to the Bengali style of sweet-and-sour cookery. Other British introductions were pumpkins, known as biliti kumro or English gourd, cabbages, cauliflowers and beans. But while the British changed the vegetables that Indians ate, they did not change the way that Indians cooked their vegetables. Just as Bengalis referred to European vegetables as an English form of an Indian vegetable, they prepared them in the same way as their Indian counterpart.26 As Gandhi commented, ‘simply boiled vegetables are never eaten. I never saw a boiled potato in India’.27 The British had a tremendous impact on the Indian diet. The introduction of European vegetables into the subcontinent significantly widened the range of vegetables available to a largely vegetarian population. However, the British had very little impact on the style and techniques for preparing vegetables.

Orchards in the cool hill stations, and market gardens around the presidency towns, meant that the British were able to buy apples and pears and European vegetables during the cold season. In his ‘Kitchen Calendar’ of available ingredients a ‘Thirty-Five Years’ Resident’ rejoiced in the long list including cauliflowers, potatoes, peas, and beans which were available in December and January, while in July he lamented that ‘the vegetable market is very indifferent . . . potatoes become poor and watery. Young lettuces, cucumbers, and sweet potatoes are now [virtually all that is] procurable.’28 For the rest of the year, and for a variety of other articles, they had to rely on imports from Britain. When Elizabeth Gwillim arrived in Madras in 1801, to start her new life as the wife of a judge, she brought with her two gammons of bacon which made her luncheon parties popular. ‘Sir S Strange and Mr Sallivan . . . came every day whilst the first lasted’, and the gammons were eaten ‘clean to the bone’. Her stores also made her popular with her Indian servants, who particularly liked English pickles. Elizabeth described how ‘their passion for these pickles is so great that they condescend to eat them though made by us whom they account the lowest of all and class with the kamars or outcasts’. These British versions of those bamboo and mango achars, which company sailors had taken home with them in the seventeenth century, had been transformed into strange and enticing delicacies for the Indian servants. Elizabeth was forced to keep the pickle jars locked away and when she required some she would dole out a little at a time on to a saucer and, even then, had to watch carefully that it appeared on the table.29

The process of hermetically sealing food in tins and jars was invented at the beginning of the nineteenth century and Anglo-Indians took full advantage of the new technology. At the European stores in the larger British settlements it was possible to buy hermetically sealed oysters, salmon, asparagus and raspberry jam; even cheese came in tins. But these products were regarded as very expensive as they cost 30 to 40 per cent more than they would have in Britain. The adventurous, who were willing to brave the ‘heat, fatigue and abominations which beset their path’ in the native bazaar, could find ‘capital bargains’.30 At the foot of the hill station of Landour, Fanny Parks discovered a wonderful bazaar where all sorts of European articles could be procured: ‘paté foie gras, bécasses trufflés, sola hats covered with the skins of the pelican, champagne, bareilly couches, shoes, Chinese books, pickles . . . and various incongruous articles’.31 But many handbooks advised that it was cheaper to bring a large store of goods with you and then have a friend or relative send a box out at regular intervals containing

Tart fruits in bottles; jams in patent jars; vinegar; salad oil; mustard; French mustard; pickles and sauces; white salt; caraway seeds; Zante currants and raisins in patent jars; dessert raisins and prunes in bottles; candied and brandy dessert fruits; flavouring essences; biscuits in tins; hams and bacon in tins . . .; cheese in small tins; salmon, lobster, herrings, oysters, sardines, peas, parsnips, Bologna sausages, mushrooms, in tins, cocoa, and chocolate; oatmeal, vermicelli, macaroni; and tapioca; if near Christmas, a jar of mincemeat.32

The vogue for tinned foods began as a result of ‘the fashionable depreciation of things native’33 but it soon grew into a fixed principle. Tinned foods became increasingly important in Anglo-Indian cookery, as they solved the problem of obtaining the necessary ingredients to create a properly British dinner-party menu. At least, they made it possible to create dishes which sounded and looked British. The drawback was that the food in the tins was often rather nasty. The tinning process was not really perfected until the Second World War and the metallic tang of tinned food could give it a ‘nauseous’ flavour. But the British dinner was less about the taste of the food than its symbolism. The Anglo-Indians stuck to their hard bottled peas, tough roasts and slightly metallic pâté de foie gras because it was a daily demonstration of their ability to remain civilised and to uphold British standards.

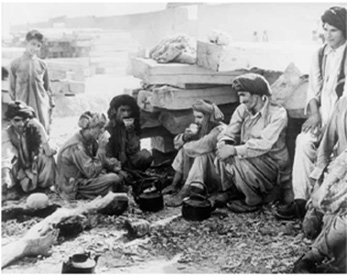

For Anglo-Indians living in remote stations, tinned foods and boxes from relatives were a rare luxury. Sometimes the closest store with a supply of European goods was at least a day’s journey away. The only available fruit and vegetables were pumpkins, gourds – ‘green, attenuated things like desiccated cucumbers which had no flavour at all’ – okra, bananas and papayas. For meat there was ‘goat-mutton and skinny moorghi [chicken] day in day out’, occasionally supplemented with game shot while out hunting. Understandably, many Anglo-Indians living in isolated areas thought a great deal about food, and placed great value on a good cook. A railway engineer and his wife were happy to overlook the fact that Abraham had just come out of prison as he produced such tasty meals.34 Although some misdemeanours could not be ignored. When one memsahib living in a distant outpost on the North-West Frontier discovered that her cook was running a small brothel in one of her spare sheds she had to sack him.35 Nevertheless, even under such difficult circumstances, the majority of Anglo-Indians adhered to the principle that curry was not acceptable for dinner and endured the tedium of tasteless approximations of British food.

One of the places where Anglo-Indian cookery really came into its own was on the railways. After the mutiny in 1857 the British constructed an efficient railway system across the subcontinent, which enabled them to transport troops around the country quickly. The standard of the food served at the station restaurant and in the dining car was similar to that provided at the dak bungalow. The train would ‘stop at a station right out in the country; just a long platform and no sign of civilisation. And there would be no sound, except for the hissing of steam and the occasional slamming of doors. Then a man would come along and say, ‘Lunch, lunch!’ and you’d detrain and walk along the platform to the dining car where you’d get in and sit down and you would be served lunch’.36 Lunch was usually curry or ‘last night’s tepid roast, euphemistically called cold meat, with thin slices of tomato and beetroot called salad’. Dinner was, of course, British: ‘thick or clear soup, fried fish or minced mutton cutlets with a bone stuck in, roast chicken or mutton, custard pudding or soufflé’. The chicken was usually as tough and stringy as dak-bungalow fowls and one English visitor to India was ‘greatly touched when on his last meal in the Madras–Bombay Express he read “Roast Foul” on the menu. He felt rewarded for all the indifferently cooked but correctly spelt fowl he had consumed on India’s railway system.’37

Of course, there were a number of highly skilled Indian cooks who could ‘put to shame the performances of an English one’.38 Goan cooks were especially sought after. It was ‘quite astonishing what [they could] . . . turn out on charcoal and a few bricks, one on top of each other’.39 These cooks introduced vindaloo into the repertoire of Anglo-Indian curries, and cookery books referred to it as a ‘Portuguese curry’. For the British, the Goans applied the techniques of vindaloo to all sorts of meats, with duck being the favourite. By the 1920s a Goan cook had become a marker of status. One of the first things Viola Bayley did, after her husband’s promotion, was to employ a Goan cook. ‘Florian [was] . . . an accomplished chef and pastry-cook. The sweets he made for dinner parties were memorable. There was a toffee basket filled with fresh fruit and cream, and a meringue trifle, and ice-cream castles of fabulous design.’40 The Goans had preserved the Portuguese talent for magical desserts and the British enthused over their chocolates, fondants and sugar-coated fruits. A classic Anglo-Indian dish known as beveca, made from sugar, rice flour, coconut cream and rose water, was a simplified version of the Goan layered coconut cake, bebinca.41

INGREDIENTS: – 1 measure of rice flour, 3 large cocoanuts, 8 eggs, 1½ lbs. unshelled almonds, sugar to taste.

MODE: Broil the rice flour, add the thick milk of the cocoanuts, 8 eggs well beaten, ground almonds and sugar to taste. Mix well together and bake in a round shallow tin.42

When the viceroy, Lord Reading (1921–5), visited the tiny princely state of Bahawalpur (sandwiched between the Punjab, Sind and Baluchistan) to install the new nawab on his throne, arrangements were made for a splendid Anglo-Indian-style banquet in his honour. ‘Goan cooks and waiters, complete with the ingredients of the meal, were specially brought from Lahore, two hundred and fifty miles away.’ For the sake of the honoured guests, ‘it had to be an English meal consisting of soup, tinned paté, salmon, also out of a tin, with white sauce, a variety of roast birds, caramel custard pudding, Kemp’s bottled coffee and a savoury on toast’. The Indian guests looked forward to this rare opportunity to taste the prestigious food of their rulers but they were ‘greatly disappointed’. They thought the plain boiled fish, ‘unsalted and unseasoned roast meats’, and the odd baked pudding were completely tasteless, while the unfamiliar knives and forks turned the meal into ‘quite an ordeal. They longed for the spicy, saffron-tinted cuisine of the palace cooks.’43

For the British the symbolic weight of English food was more important than the fact that it was bland and uninteresting. Soup and roast meat, custard and pudding, were all essential elements in the maintenance of prestige. Those Indians who adopted the cuisine of their rulers did so for similar reasons. Nawab Sadaat Ali Khan of Lucknow (1798–1814) employed a French, an English and an Indian cook, and the wife of a British army officer observed that ‘three distinct dinners’ were served at his table. By the time Sadaat Ali Khan came to the throne he was well aware that the tide was turning in favour of the British. Before his accession he had spent many years in Calcutta, and when he returned to Lucknow he set about Anglicising the court. Besides the French chef, he brought with him a suitcase packed with an English admiral’s uniform, a parson’s outfit and some of the latest fashions in wigs. He redecorated the palace in English style with ‘gilt chairs, chaises longues, dining tables, swagged velvet curtains and a profusion of chandeliers and girandoles’, and the various different dinners were all served on the best English china.44

Sadaat Ali Khan was one of the first in a long line of Indian princes who incorporated the dominant culture of the British into their courts. By the end of the nineteenth century many Indian princes had received English educations, either from an English tutor, or at a public school, in either Britain or India. A great many of them led semi-Indian, semi-European lives. Often their wives maintained the Indian side of things, continuing to live in separate quarters, furnished in Indian style, and wearing traditional dress, while in their kitchens they supervised the preparation of exquisite Indian dishes. In contrast, the public areas of the palace were a statement of the successful acquisition of British culture, in the furnishings, the food served on the dining tables and the daily routine of the ruler himself. The Gaekwar of Baroda is a good example. Just before the First World War he was visited by the tiresomely sycophantic Reverend Edward St Clair Weeden, who wrote a book about his visit in which he described the Gaekwar’s daily routine: chota haziri (little breakfast), followed by a ride, breakfast and a morning playing billiards and receiving visitors. After tiffin the maharaja worked while his son and his guest took a rest, played tennis or cricket or went for a drive. Dinner was succeeded by billiards, bridge and bed. The Gaekwar employed a number of English servants, including a valet, ‘a capital fellow named Neale from the Army’, a French cook, and an English maître d’hôtel who had been butler to Lord Ampthill when he was Governor of Madras.

The Gaekwar’s dining habits established his status as a gentleman. His breakfasts, Weeden claimed, were ‘very much what you would get at a first class restaurant in London’. At dinner there were ‘two menus, as the ladies [the maharani and her daughter] may prefer to have Indian dishes, which are served on large golden trays, placed before them on the table’. The maharani insisted that he should taste some of these Indian dishes. Rather churlishly, Weeden complained that this ‘made the dinner rather long’, although he did enthuse over her pilaus: ‘made of beautifully cooked dry rice, chicken, raisins, almonds and spicy stuffing, covered with gold or silver leaf which gives it a very gay look. It is served with a most delicious white sauce flavoured with orange or pineapple.’45 Weeden seems to have been unaware that his hostess was something of a gourmet. Her granddaughter remembered that the food from her kitchen was always superb, whether it was ‘the Indian chef who was presiding or . . . the cook for English food’. ‘She spent endless time and trouble consulting with her cooks, planning menus to suit the different guests . . . Her kitchen was particularly well known for the marvellous pickles it produced and for the huge succulent prawns from the estuary.’46

The maharani of Baroda passed this love of fine food on to her daughter, Princess Indira, who married into the princely family of Cooch Behar. This family employed three cooks: ‘one for English, one for Bengali and one for Maratha food’. (Cooch Behar is in Bengal and Princess Indira was a Maratha princess.) Each had his own kitchen, scullery and assistants. The Cooch Beharis were a very modern, westernised family. They moved in the best circles of British as well as Indian society and travelled widely in Europe. Princess Indira was thus exposed to a variety of cuisines. She encouraged her kitchen staff ‘to experiment and introduced them to all kinds of unfamiliar dishes’. She is said to have taken one of her cooks to Alfredo’s in Rome because she wanted him to understand what Alfredo’s pasta tasted like. Thus, some princely households outdid the British on their own ground. The British food served at their tables was not the boarding-house level common in Anglo-Indian society but demonstrated a mastery of the various sophisticated cuisines of Europe.47 Other princely families just went through the form of consuming European food, without caring for it. Prakash Tandon witnessed this phenomenon among a family of maharajas in Hyderabad in the 1930s. Invited to lunch by a prospective son-in-law of the family, Tandon was eager to escape ‘the eternal roast mutton and Anglo-Indian curry at the hotel’ and went along expecting ‘a moghlai feast’:

To my astonishment the meal began with a watery soup and followed its course through indifferently-prepared English dishes – mince chops with bones stuck in, fried fish, roast mutton and a steamed pudding. Instead of the famed Hyderabadi moghlai cooking I faced a meal as dull as my daily hotel fare. I accepted my fate, but noticed that the family only picked at their food, which I attributed to their noble blaséness. My friend managed to whisper that the English meal was a touch of modern formality of which no one took notice; the real meal was yet to follow, and it did. As soon as the pudding was removed, there began an unbelievable succession of dishes served in beautiful Persian-style utensils: pullaos and biryanis, naans and farmaishes, rogan joshes and qormas, chickens, quails and partridges, upon which the family . . . fell to. Indifference gave way to healthy vocal appetites, and I followed suit with my second lunch.48

British attitudes to Indian attempts to assimilate European culture into their courts were often condescending. Central to the justification of British rule was the assertion that Indians were incapable of achieving civilisation on their own. It therefore undermined British self-confidence to acknowledge that Indians did understand and suavely adopt their ways. The army wife who visited the court of Sadaat Ali Khan claimed that while she was in Lucknow a misunderstanding arose over chamber pots. A set of Worcestershire china had arrived from England and in celebration the nawab had invited the British inhabitants to a breakfast. The table looked splendid except for about twenty chamber pots placed at intervals in the centre of the table, which the ‘servants had mistaken for milk bowls’. Surprised by his guests’ reluctance to drink the milk, ‘the Nawaab innocently remarked, “I thought that the English were fond of milk.” Some of them had much difficulty to keep their countenances.’49 Such mistakes, or a weakness for garishness, were interpreted as a sign that the Britishness of Indians was always a thin and fragile veneer. Lady Reading’s personal secretary regarded the gaudy palace of the Maharaja of Bikaner as a sign that his ‘Europeanism . . . for all its show, [was nothing] more than skin deep’. Unfortunately, a number of maharajas appeared to confirm this British conceit by displaying a weakness for foolish European things. The Maharaja of Scindia’s palace was like a ‘pantomime palace and rather fun, I think. Vast chandeliers, glass fountains, glass banisters, glass furniture and lustre fringes everywhere. It is really amusing and comfortable.’ He also had a vulgar device for delivering after-dinner drinks and sweets: ‘Then he pressed a button – and the train started. It is a lovely silver train, every detail perfect, run by electricity and has seven trucks – Brandy – Port – cigars – cigarettes – sweets – nuts – and chocolates. If you lift the glass lining to the truck or a decanter the train stops automatically. It is the nicest toy – and perfect for a State Banquet!’50

Maharajas were not the only Indians to adopt British habits. The British introduced an English system of education into India in the hopes that this would foster a collaborative elite, in the now well-worn phrase of Thomas Macaulay, ‘Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect’.51 In and around the presidency towns, and particularly in Calcutta which was the seat of British government, new business opportunities created by British commerce, the reform of the Indian judicial system and eventually the creation of parliamentary institutions, generated jobs for the Western-educated Indians. Alongside the Indian sepoys in the army, these clerks, lawyers, doctors, publishers, engineers and teachers provided a raft which kept the British Raj afloat, and they began to adopt aspects of the dominant British culture. As early as 1823, Bishop Heber noticed that among the wealthy Indians ‘their progress in the imitation of our habits is very apparent . . . their houses are adorned with verandahs and Corinthian pillars; they have very handsome carriages often built in England; they speak tolerable English, and they shew a considerable liking for European society’. The 1832 Select Committee, investigating the sale of British goods in India, found that Indians had developed a taste for wines, brandy, beer and champagne. Yet as Heber remarked, ‘few of them will . . . eat with us’.52

European travellers to Mughal India were often disconcerted when their Indian hosts simply sat politely by and watched them eat, but would not touch any food in their presence. The East India Company surgeon, John Fryer, commented that ‘every cast in India refuses to eat with those of contrary tribe or Opinion, as well as Gentues, Moors, and Persian, as any other’.53 Anglo-Indians in the nineteenth century were surprised and shocked to discover that they were considered impure by the majority of their supposedly inferior subjects. This was forcibly demonstrated to Mrs Deane, travelling upriver in the early nineteenth century. Every evening the boatmen would prepare their food on the river banks. First, they would carefully create a flat circle of mud, at the centre of which they would place their stove. ‘A number of these plans had been formed on the ground near our boat, and being ignorant at that time of their customs, I unfortunately stepped into one of the magic circles in my attempt to reach the high land.’ Nothing was said, but when she reached the top of the river bank and turned to look at the view she observed the boatmen ‘emptying the contents of their cooking pots into the river, and afterwards breaking the earthen vessels in which their food had been dressed’. By stepping inside the circles, she had polluted the food and made it impossible to eat. As there was no village nearby the boatmen had only parched grain to eat that evening.54

As the British became a powerful presence in India, the question of inter-dining became more pressing. For the British, sharing food was an important way of cementing bonds and creating friendships. Some Indian communities found it easier to compromise than others. The fact that the British tended to employ Muslim cooks and waiters meant that Muslims would often overlook their scruples, as long as no pork was served. The Parsee merchant community in Bombay was particularly enterprising and adaptable. By the end of the nineteenth century, a high proportion of Bombay’s factories and businesses were owned by Parsee gentlemen, who dressed like the British, ate at dining tables and, if they were very wealthy, employed three cooks, to make Goan, British and Parsee dishes.55

The group which most enthusiastically embraced Western education were the Bengali Hindus. Under the Mughals, Muslims had dominated in government positions, but as power was transferred to the British they were slow to adapt and reluctant to learn English (the language of government had been Persian). The Hindu community quickly stepped in and grasped the new opportunities offered by a Western education. And yet the Hindus were the community for whom westernisation caused the most problems. Orthodox Brahmans were said to take a purifying bath after any contact with Europeans who ‘contaminated themselves by eating beef, by the employment of cooks of all castes, and by allowing themselves to be touched by men and women of even the lowest castes’.56

Some members of the Indian middle classes firmly rejected the adoption of British dining habits, let alone eating with Englishmen. In fact, many Indians employed in the British administration increased their observance of Brahminical rituals of distinction as a way of demonstrating their newly elevated social status. But, as educational and employment opportunities increased, Indians wishing to take advantage of them became increasingly vocal in their criticism of caste taboos. The evidence of an evangelical vicar in the 1820s may have been wishful thinking, but he claimed that ‘in numerous instances, we find that groups of Hindoos, of different castes, actually meet in secret, to eat and smoke together, rejoicing in this opportunity of indulging their social feeling’.57 Influenced by Western philosophy, a number of Bengali intellectuals criticised Indian culture, arguing that the caste system was an anachronistic obstacle to social progress. When Bhudev Mukhopadhyay, a future member of the Hindu revivalist movement in Bengal, attended the Hindu College in Calcutta in the 1840s, he discovered that ‘open defiance of Hindu social conventions in matters of food and drink was then considered almost de rigeur by the avant garde students of the College. To be reckoned a civilised person, one had to eat beef and consume alcohol.’58

Meat-eating among educated Indians was a response to the British claim that vegetarianism was at the root of Indian weakness. By the end of the nineteenth century, the British were less enthusiastic about the creation of a westernised Indian elite. They found that they had placed their own weapons in their subjects’ hands. Armed with an understanding of Western philosophy and politics, educated Indians were able to demonstrate the injustices of imperialism using the rhetoric of their rulers. They began to demand their right to participate in the government of their own country. In retaliation, the British denigrated educated Indians, arguing that they were too degenerate to govern themselves. In the early nineteenth century, the British had argued that the steamy climate and frugal vegetable diet made all Bengalis languid and feeble. Now, in an attempt to justify their racially discriminatory policies, the British specifically labelled educated Indians as weak and effeminate.59

British arrogance, the fact of their ability ruthlessly to subdue Indians and impose their rule over them, and the assertion that this overwhelming power was, at least in part, derived from their meat-based diet, all gnawed away at Indian self-confidence. Faced with the incontrovertible fact that they were a subject people, educated Indians worried that their diet had made them feeble. This idea occurred to Gandhi growing up in Gujarat: ‘It began to grow on me,’ he explained, ‘that meat-eating was good, that it would make me strong and daring, and that, if the whole country took to meat-eating, the English could be overcome.’60 He and a group of friends experimented by roasting a goat. But the meat was like leather and Gandhi suffered from a guilty conscience. That night he dreamed that the goat was bleating inside him. ‘If my mother and father came to know of my having become a meat-eater, they would be deeply shocked. This knowledge was gnawing at my heart.’61

When Gandhi decided to travel to London to study law in 1888, he was faced with the problem that Indians who travelled to Britain to study or to take the entrance examination for the Indian Civil Service were deemed to have lost caste. Overseas travel was considered polluting, added to which, while travelling, it was necessary to eat food cooked by non-Brahmans, and possibly in the presence of Englishmen. In order to please his mother, he took a vow that he would abstain from wine, women and meat during his stay in England. Nevertheless, the caste elders designated him outcaste and even a purification ceremony on his return did not redeem him in the eyes of the orthodox members of his community.62 For Gandhi, like many of his fellow students, the alternative world which his education would open up to him made him indifferent to the loss of caste. In fact, Gandhi was determined to transform himself into an English gentleman. On arrival in London he took dancing, elocution and violin lessons and spent too much money on clothes.63 Nevertheless, he intended to remain a vegetarian. His one foray into the world of meat eating had put him off for good. Consequently, food in Britain became an enormous problem for him.

The family Gandhi initially lodged with in London were completely stumped by his vegetarianism. As a result, he lived on a stodgy and unhealthy diet of soup, potatoes, bread, butter, cheese and jam with an occasional piece of cake. It was not until he discovered one of the few vegetarian restaurants in London at that time, and moved into lodgings where he could cook for himself, that his diet, and his spirits, improved.

Food was always on Gandhi’s mind when he lived in Britain, and later he wrote a Guide to London for the benefit of Indian students like himself. Almost half of it was devoted to the problem of what to eat. On the ship out, he recommended gradually increasing the number of European dishes the student ate, in order to habituate himself to the British diet. One problem was that ‘there could have been no worse introduction to English cooking [than the food served on the steamships]. Boiled, floury potatoes, raw leaves of lettuce and tomatoes, cold grey and pink, spongy slices of mutton and thick boiled wads of watery cabbage, all unsalted and unflavoured.’64 Once in Britain, Gandhi observed that with time and money it was perfectly possible to observe all caste rules and cook your own food, but ‘for an ordinary Indian who is not overscrupulous in his religious views and who is not much of a believer in caste restrictions, it would be advisable to cook partly himself and get a part of his food ready made’. He was particularly keen on porridge, and gave instructions on how to make it. In fact, apart from the meals he ate at the vegetarian café, Gandhi seems to have lived on porridge, to which he added sugar, milk and stewed fruit.65

Indian students in Britain were pressurised to eat meat. The British believed that the animal energy contained within meat was essential to sustain the body in a cold climate. Gandhi was told he would die without meat. Indeed, the British faith in its mythical power was quite equal to the Indian faith in the purifying and polluting potential of food. Victorians were cautious about giving meat to women or sedentary scholars as it was believed to arouse passions which, finding no outlet, would lead to nervous introversion and illness. But it was regarded as the ultimate food for the strong, aggressive and manly Englishman.66 Like Gandhi, Behramji Malabari, an Indian tourist in Britain, was horrified by the carcasses of animals hanging in the shops. ‘The sight is invariably unpleasant and the smell is at times overpowering . . . It is an exhibition of barbarism, not unlikely to develop the brute instincts in man.’67 But a great many Indian students quickly gave up the struggle to remain vegetarian. A diet of porridge was not very appealing, and the majority lacked Gandhi’s qualities of stubborn perseverance. In fact, they revelled in ‘the sense of freedom [and] liberty from social restrictions’.68 A few even developed a liking for fish and chips, tripe and onions, and black pudding.69

Indian students in Britain were joined in their rebellion by ‘apparently orthodox Babus’ in India who could be found ‘in convenient European hotels in Calcutta and elsewhere, [enjoying] a hearty meal of forbidden food, cooked and served up by Muhammadans’. It is possible that they consumed British food in the hope that they might absorb some of the essences which made the British so powerful.70 Besides, strict observance of caste restrictions had few benefits for a lowly office clerk. No matter how scrupulous he was in his eating habits, no Indian from the upper echelons of the caste or class system would deign to dine with him. Instead, he derived a certain satisfaction from the fact that ‘if he cannot eat with the Brahman, he can do so with the Sahibs who rule India’.71

During the 1920s and 30s, Indianisation of the services and political reform meant that pressure increased for both sides to find ways of working and socialising together. Wealthy Indians responded by installing in their houses English kitchens, staffed by Muslim cooks. This meant that they could provide for British guests without compromising their own vegetarian kitchen. Reforming British administrators counted it a triumph to be invited to eat with their Indian colleagues. When Henry Lawrence was invited to dine at the home of a Brahman friend of his, where he was served by the women of the family, he considered it ‘the greatest compliment he has ever received’.72 The British made allowances on their side and would often provide Indian food for their guests. When Lord and Lady Reading had the Shafi family for dinner, they provided ‘Persian Pilaw for dinner – so good. Pink and green rice with curry and Mangoe chutney.’ For less relaxed guests, special arrangements were made and at her purdah party Lady Reading provided the Hindu ladies with separate metal plates and mugs, and lemonade and fruits prepared by Brahman cooks.73

The British, however, were always most comfortable with less educated Indians, where there was no pretence of equality. In the 1930s, Prakash Tandon worked as an advertising executive at the British firm Unilever. He described how the Indian agent for the firm at Amritsar, ‘old Lala Ramchand’, would invite the sahibs and their wives to his home where he would ply them with Indian sweets, spicy savouries, sickly rose- and banana-flavoured sodas and milky sweet tea, ‘with cheerful unconcern for the gastronomic capabilities of the protesting sahib’ who did his best to disguise his fear of ‘lifelong dysentery’. But when the thoroughly westernised Tandon and his Swedish wife attempted to socialise with his British colleagues it was a failure. The British made it clear that they would find Indian food unacceptable, explaining that although they liked their curry and rice on Sundays, made to their taste by a Goan cook, they did not want to eat it more often. The Tandons compromised and served Swedish food but they could find no neutral topics of conversation and they never received a return invitation. ‘This lack of response soon stifled my good intentions, but left me a little sad.’74

Meanwhile, educated and thoroughly westernised Indians were made to feel uncomfortable by the example of Gandhi. The same young man who had set off for London determined to transform himself into a proper English gentleman had, by the 1930s, metamorphosed into a dhoti-clad ascetic, who nibbled on the occasional fruit or nut, and had carefully eradicated Western influences from his daily life. Gandhi’s bold celebration of the Indian body was a powerful challenge both to the British and to westernised Indians. Following his example, a number of Indian campaigners for independence flung away their ‘Savil Row suits’ and donned home-spun cotton, renounced their ‘roast lamb, two veg. and mint sauce’, furtively consumed in British restaurants, and replaced them with vegetarian rice and dhal.75 But even Gandhi seems not to have altogether abandoned British table etiquette. When he died, among his few possessions were a couple of forks.76

After the First World War the Britishness the Anglo-Indians so self-consciously preserved became increasingly out of date. Newcomers to India in the 1920s and 30s felt as though they had been transported back in time. One memsahib described how she ‘stepped into an almost Edwardian life . . . The bungalow was large and old-fashioned, tended by an army of servants . . . we rode every morning before breakfast . . . Life was very formal. Winifred and I would be driven out to the shops or to pay calls in the morning, for which . . . one wore hat and gloves . . . In the afternoon . . . one rested or wrote letters.’ Socialising consisted of race meetings, garden parties, polo meets and formal dinner parties.77

Anglo-India had failed to keep pace with social change in the home country. The dinner parties seemed convention-bound and old-fashioned. In Britain it was becoming less common to dress for dinner, but Anglo-Indians continued to insist on it, and everyone still sat at the table, no matter how small the party, in order of precedence. This insistence on stiff formality struck many as pompous and slightly absurd. In the nineteenth century, Anglo-Indian pseudo-British dishes had been recognisable approximations of those eaten at home. Post-1919, the food seemed odd. Savouries had been relegated to formal dinners in Britain, but even on the most ordinary occasions Anglo-Indians still served what they referred to as ‘toast’ after the dessert. Usually this was something like sardines, or mashed brain spiced with green chillies on toast.78 The Victorians had delighted in trompe l’oeil jokery. The famous chef Alexis Soyer loved to surprise his guests by making a boar’s head out of cake, or saddles of mutton out of different coloured ice creams.79 Like the Nawab of Oudh’s inventive cooks who were able to manufacture realistic biryanis and kebabs out of caramelised sugar, the Anglo-Indians’ cooks had a penchant for food trickery. It was not unknown for them to cheer up the dull food by dyeing mashed potatoes bright red and boiled carrots purple. But this sort of thing was now hopelessly out of date. Curry was rarely served for dinner and it was possible for a British person to live in India without ever trying one.

Curry survived in a few niches of Anglo-Indian life. In Calcutta in the 1930s, the clubs would serve curries for lunch at the weekends. After a round of golf in the mornings, the men would meet up with their wives at the club, where prawn curry was usually on offer. Club curries reduced the subtleties of Indian food to three different bowls, labelled hot, medium and mild. The Sunday ritual was completed by a siesta and the cinema. Some households included mulligatawny soup for breakfast in the ritual.80 On the P&O boats which linked India to Britain, curry was served alongside the roast joints at dinner, and on the trains it survived in the guise of ‘railway curry’, as it was referred to by the Maharani of Jaipur’s family. ‘Designed to offend no palate [it contained] no beef, forbidden to Hindus; no pork, forbidden to Muslims; so, [it was] inevitably lamb or chicken curries and vegetables. Railway curry therefore pleased nobody.’81 Both the British and the Indian army messes kept up the tradition of curry lunches. In 1936 Edward Palmer, caterer to the Wembley exhibition of 1924–5 and founder of Veeraswamy’s Indian restaurant, was invited to lecture to the army cooks at Aldershot on curry-making. During the Second World War trainee cooks in the army catering corps were taught how to make curries by adding curry powder to a roux of flour, and army stock books show that cooks were allotted supplies of curry powder each month. Major Eric Warren, who served with the Royal Marines from 1945 to 1978 ate curry throughout his career in officers’ messes from Hong Kong to Cyprus and the West Indies. A standard item on the Sunday-lunch menu, they were always accompanied by an array of side dishes, including sliced bananas, pieces of pineapple and poppadoms. Slightly sweet yellow curries, dotted with raisins and made with fantastical fruits, were still served in British army messes in the 1970s and 80s.82 Indeed, the army and the merchant navy were two important routes by which Anglo-Indian curries found their way to Britain. It was on board ship and in messes, during the Second World War, that many British men who had never travelled before were introduced to curry.83

After Indian independence in 1947, the self-contained world of Anglo-India was maintained among the British businessmen who ‘stayed on’. Club life continued, cucumber sandwiches and sponge cake were served at tennis parties, and savouries still appeared at dinner parties.84 At Queen Mary’s School, Bombay, run by Scottish missionaries, Camellia Panjabi and her fellow pupils were treated to ‘baked fish, baked mince (cottage pie), dhol (English and Anglo-Indian for dhal) and yellow rice, mutton curry and rice, coconut pancakes, and Malabar sago pudding’. It was only when she went to university in Britain that it became clear to her that real British food ‘had none of the spices and seasonings that we had experienced as children in “English food” in India. It was then that I realised that “Indian English food” was a sort of hybrid cuisine in its own right.’85 On the railways and in dak bungalows stringy chicken and masala omelettes survived for a while. The Bengalis, fond of sweets, have adopted a few British desserts such as caramel custard and trifle.86 And in guest houses in Calcutta minced meat and mashed potato cutlets or chops are still on the menu. Soggy chips and vegetable cutlets served with a sachet of tomato ketchup, some toast and a cup of tea are standard breakfast fare on Indian trains.87 The dislocated Anglo-Indian community of mixed British and Indian heritage still eat stew and apple crumble. At the Fairlawn Hotel on Sudder Street in Calcutta, the white-gloved waiters politely hand round roast buffalo. The meal is finished with a savoury of sardines on toast.88 And at the Bengal Club in Calcutta the burra khana lives on: with one attentive bearer to every dinner guest and mulligatawny soup, ‘chicken dopiaz’ and orange soufflé on the menu.89

Despite the fact that remnants of Anglo-Indian cookery clung on in odd corners of the subcontinent, an English roast was surrounded by an aura of the exotic for the young author Manil Suri, growing up in Bombay in the 1970s. Inspired by the novels of Enid Blyton, which were filled with picnics, and by an English cookery book picked up at the local store, he longed to taste tongue sandwiches, scones and a roast lamb. But it was impossible to find the ingredients and his mother’s kitchen was not even equipped with an oven. After several attempts, which produced ‘grey and flabby’ boiled goat and an utterly inedible Neapolitan soufflé, to his family’s relief Suri gave up.90

The British introduced the Bengalis to the potato but no self-respecting Indian cook would have produced plain boiled vegetables. The Bengalis quickly incorporated European vegetables into their own recipes, and this particular way of cooking potatoes results in an unusual sweet-sour flavour. Serves 4–6.

5–6 tablespoons vegetable oil

3cm stick of cinnamon

4 cardamom pods

4 whole cloves

2 bay leaves

2 onions, very finely chopped

10 cloves garlic, crushed

½–1 teaspoon chilli powder

1 teaspoon turmeric

500g small new potatoes

1 tablespoon tamarind pulp mixed with 250ml warm water

salt to taste

jaggery (or soft brown sugar) to taste

Heat the oil. When it is hot throw in the cinnamon stick, cardamom pods, cloves, and bay leaves, and fry for about 1 minute. Add the onions and fry until they brown. Add the garlic and fry for another 6 minutes. Then add the chilli powder, turmeric and the potatoes. Fry, stirring constantly, until the potatoes are coated in the spice mixture. Add the tamarind pulp mixture, the salt and jaggery, and bring to the boil. Then turn the heat low and simmer until the potatoes are done. You may need to add more water to prevent the sauce from burning.