ONE MORNING IN 1936 a ‘special demonstration unit’ arrived at the door of a wealthy Nagarathar family in the provincial town of Karaikudi (Tamil Nadu). The special unit, consisting of ‘an experienced and senior Sub-Inspector and an Attender’, was ushered into the house where they set up their equipment: a small stove, a kettle, milk jug, sugar basin, china cups and saucers, and a teapot. The kettle was set to boil and the ladies of the family were shown how to pour the boiling water over a carefully measured amount of tea. Once it had brewed for the required period, the golden liquid was poured into the china cups and the process of adding milk and sugar was demonstrated. The tea was then handed round to the members of the family who had gathered round to watch. The special unit were working for the Indian Tea Association and the Nagarathars were a small but influential sub-caste who had resisted earlier attempts by the Tea Association campaigners to persuade them to drink tea. They had been buying half-anna packets of tea, but had been giving them away to their servants. Apparently, the fact that previous tea demonstrations had used tea prepared in the homes of their lower-caste neighbours had proved offensive. Determined to change their ways, the special unit had abandoned the tea urns usually used to make demonstration tea and had set about wooing 240 Nagarathar families in Karaikudi with freshly boiled water and elegant china cups. The unit’s efforts were successful and the tea demonstrations became an event in the households they visited. By the end of four months, 220 of the Nagarathar families had been converted to tea drinking.1

The Nagarathars’ refusal to drink tea was by no means exceptional. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the majority of Indians did not know how to make a cup of tea and were reluctant to drink one.

Now that India is both the world’s major producer and consumer of tea, this seems incredible. It confounds the myth that the British acquired their love of tea from their Indian subjects. In fact, it was the British who introduced tea to the Indians. Although they barely changed the way Indians eat, the British radically altered what they eat and drink. While the introduction of a wide variety of European and American vegetables to India was an inadvertent by-product of British rule, the conversion of the population to tea drinking was the result of what must have been the first major marketing campaign in India. The British-owned Indian Tea Association set itself the task of first creating a new habit among the Indian population, and then spreading it across the entire subcontinent.

Tea drinking began in China during the fourth century. From China, it spread to Japan sometime between the sixth and eighth centuries, where it became an important social ritual. It also spread into Tibet and the Himalayan regions north of India, where tea was drunk as a kind of soup mixed with butter. On the eastern fringes of India, in Assam and further east in Burma and Thailand, the hill tribes chewed steamed and fermented tea leaves.2 Despite being bordered by tea-drinking (or -chewing) countries, India remained impervious to the charms of tea. When the interpreter for the Chinese Embassy of Cheng Ho visited Bengal in 1406, he was surprised to note that the Bengalis offered betel nuts to their guests rather than tea.3 Coffee had been introduced into India by the Arabs, Persians and central Asians who found employment under the Mughals. The young German traveller, Albert Mandelslo, who passed through Surat in 1638, noticed that the Persians ‘drink their Kahwa which cools and abates the natural heat’. Coffee houses could be found on Chandni Chowk, Delhi’s main thoroughfare. ‘An innovation from Persia, these were places where amirs [Mughal noblemen] gathered to listen to poetry, engage in conversation, and watch the passing scene.’4 Moplah Arab traders had introduced coffee to the west coast, and the south-western hills were dotted with tiny coffee gardens.5 For the most part, however, the coffee-drinking habit was confined to wealthy Muslims and did not spread to the rest of the population.6 As the chaplain Edward Terry noticed, Indians preferred water: ‘That most antient and innocent Drink of the World, Water, is the common drink of East-India; it is far more pleasant and sweet than our water; and must needs be so, because in all hot Countries it is more rarified, better digested, and freed from its rawness by the heat of the Sun, and therefore in those parts it is more desired of all that come thither.’ In northern India the villagers also drank buttermilk, a by-product of the Indian way of making ghee, by churning yogurt (as opposed to the European method of churning cream). If they wanted something stronger, they drank arrack or toddy.7

European East India merchants brought tea with them to India from China. Indian textiles could be exchanged there for Bohea (black) and green tea as well as for silks, hams, Chinese jars, quicksilver and vermilion.8 Mandelslo, who noticed the Persians drinking coffee, observed that ‘at our ordinary meetings’ the English at Surat ‘used only Thé, which is commonly used all over the Indies, not only among those of the Country, but also among the Dutch and English’.9 Indeed, the Dutch were said to be so fond of the brew that among them the teapot was ‘seldom off the fire, or unimploy’d’. Under the influence of the East India merchants, the Banians at Surat learned to drink ‘liberal Draughts of Tea and Coffee, to revive their wasted Spirits, any part of the Day’.10 But Mandelslo was mistaken in his assumption that tea was used as a refreshing drink by the entire Indian population. Even in the nineteenth century Indians stubbornly regarded tea as a medicine. An Englishwoman living in Lucknow in the 1830s observed that ‘china tea sets are very rarely found in the zeenahnah; . . . The ladies . . . must have a severe cold to induce them to partake of the beverage even as a remedy, but by no means as a luxury.’11 Prakash Tandon’s great-uncle, who was a pandit in the law courts of Punjab in the 1860s and 70s, would take a glass of milk, almond or fruit juice at four o’clock but ‘tea was unknown in those days except as a remedy for chest troubles’.12

Tea was initially used by monks in China (and later in Japan) as a herbal remedy for headaches and pains in the joints, as well as an aid to meditation. But it fairly rapidly became a favourite everyday drink with the majority of the population. Similarly, among the other nationalities who took up tea, it was first adopted as a medicine. The Dutch in India, who constantly had the teapot boiling, would mix it with spices and add sugar or conserved lemons, and even sometimes a slosh of arrack, to mix up a pleasant cure for headaches, gravel, ‘Griping in the Guts’ and ‘Twistings of the Bowel’.13 Mandelslo attributed his recovery from burning fever and bloody flux to the tea which he drank on an English ship sailing across the Persian Gulf to Surat.14 In Britain, Mrs Pepys famously tried drinking tea in 1667 as a cure for ‘cold and defluxions’.15 Among all these nationalities tea quickly escaped from the medicine cabinet and found itself a secure home in the kitchen cupboard. In India, however, it remained firmly in the category of herbal remedy (even today Bengalis regard tea mixed with ginger juice as a cure for colds),16 and the tea-loving British were forced to carry their own supplies of tea leaves when they travelled into the Indian countryside, as it was impossible to buy tea there.17 But the British-run Indian Tea Association was to change all this.

In 1823 Robert Bruce, stationed as a British agent in Assam, noticed the Singpho people drinking an infusion of the dried leaves of a plant that looked suspiciously like Camellia sinensis, in other words tea. He wrote to his brother Charles, who later reminded the government that ‘I was the first European who ever penetrated the forests and visited the tea tracts in British Sadiya, and brought away specimens of earth, fruit and flowers, and the first to discover numerous other tracts’.18 Charles Bruce’s injured tone arose from the fact that the British government paid absolutely no attention to his discovery. Then, in 1834, Lt. Andrew Charlton of the Assam Light Infantry, also stationed in Sadiya, persuaded the authorities in Calcutta to investigate the possibility of growing tea in India. Charlton later received a medal for discovering tea in India, much to Bruce’s chagrin. But Charlton’s timing was better. At the end of the 1820s the British East India Company became concerned that they might lose their monopoly of the China trade, which they did in 1833. Given that tea was their main import from China, accounting for £70,426,244 of the £72,168,541 made from the China trade between 1811 and 1819, they had an interest in finding an alternative source of tea.19 In addition, the Chinese reliance on small householders, who grew tea on their tiny plots of land, was a haphazard, labour-intensive and unreliable way of producing a commodity which had become vital to the British. The company was required to keep a year’s supply in stock at all times, to protect the British public from supply shortages.20

By the end of the eighteenth century, tea had become the British drink. At first a herbal remedy for the wealthy elite, it soon became a fashionable beverage. It provided a good replacement for the glass of sweet wine which aristocratic ladies used to take with a biscuit in the afternoons, and it allowed them to show off their collections of delicate porcelain tea bowls. In the 1730s, a direct clipper link with China and a reduction in taxes on tea meant that it became affordable for nearly everyone. In 1717, Tom Twining had two adjoining houses in London, one selling coffee and the other tea. By 1734, the consumption of tea had taken off to such an extent that he sublet the coffee house and concentrated on selling tea.21 Tea suited the new middle-class lifestyle perfectly. Served with bread and butter and cake, it tided middle-class ladies over until dinner, which was now eaten much later, as the gentleman of the house did not come home from his office until after five o’clock. It was also popular among the labouring classes. With the addition of sugar it made an energising drink and in 1767 road menders were observed pooling their money to buy tea-making equipment. Haymakers developed a preference for cups of tea rather than glasses of beer.22 Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor noted that tea and coffee had replaced saloop (the powder of an orchid imported from India) and sugary rice milk.23 By the early 1830s, the East India Company was importing approximately 30 million pounds per annum which translated into each person in the country drinking about a pound of tea a year. This provided the Exchequer with £3,300,000 in duty, or one-tenth of its total revenue.24 It therefore made perfect sense when Governor-General William Bentinck appointed a tea committee in February 1834 to look into the idea that India might be a good place to set up the company’s own tea production under the latest efficient means of agricultural production.25

Initial British attempts to cultivate tea in India were something of a shambles. The committee decided that the Assamese climate would be suitable for an experiment in tea cultivation but they did not believe that the indigenous plant which Bruce and Charlton had seen growing there was suitable for tea production. G. J. Gordon was therefore dispatched to China to collect seedlings and to recruit Chinese who knew how to make tea. Although Europeans had been eagerly buying tea from the Chinese for over two centuries, they were still uncertain as to the precise production methods. These were secrets that the Chinese guarded jealously. It was extremely difficult to gain access to the tea manufactories and the Chinese would chase, and attempt to capture, any ship they suspected of smuggling out plants or seeds.26 Gordon must have been a resourceful man as he duly sent back 80,000 tea plants in 1835, and two Chinese tea producers a couple of years later.27 Their advice was much needed as the motley crew of Chinese carpenters and shoemakers living in the bazaars of Calcutta who had been sent to Assam as advisers ‘had never seen a tea plant in their lifetime’ and had no idea how to pluck or treat the leaves. The Assamese, whose land had been requisitioned to create tea gardens, refused to work in tea cultivation, and to make matters worse, the Chinese tea plants failed to thrive. By the time the British had decided that the indigenous Assamese tea plants were in fact perfectly good for making tea, these had interbred with the Chinese plants, resulting in an inferior hybrid.28

Despite all these problems, the tea growers of Assam managed to produce twelve chests of tea in 1838. These were auctioned in London the following year to very little acclaim.29 Old, hard leaves which had been over-plucked, and then transported long distances before being processed, made poor-quality tea. Initially, Assam tea was so inferior it could barely compete with even the worst grades from China. Nevertheless, the company handed over its plantations to the newly founded Assam Tea Company in 1840, though it was not until 1853 that Assam tea paid its first dividend.30 In 1861, tea mania struck and retired army officers, doctors, engineers, steamer captains, shopkeepers, policemen, clerks, even civil servants with stable positions, scrambled to buy tea plantations or to get work as planters. These enthusiastic novices bought up and cleared unsuitable land and planted it out with tea. In 1865, they realised they would never make a profit, and the tea-mania businessmen sold in a panic and prices crashed. Unsurprisingly, the quality of the tea produced the next year was so abysmal that prices fell again and more tea gardens failed. It was not until the 1870s that the tea industry in India stabilised and finally began producing good-quality tea for a profit.31

Among the Indian population, a comparable rush brought even greater misery to India’s poor. Contractors, who became known as ‘Coolie Catchers’, hired desperate peasants as labour for the tea plantations. The first stage of the journey to the gardens on packed and insanitary boats resulted in the deaths of many of the labourers before they reached their destination. Once the survivors arrived, their living conditions were basic, disease was rife, and many of them suffered from enlargement of the spleen, which is a side effect of malaria. This meant that when their employers kicked or beat them (which happened lamentably often) they frequently died from a ruptured spleen. The only medical treatment available came from their medically incompetent employers and a few doctors. Life on the tea plantations was terrible for the workers.32

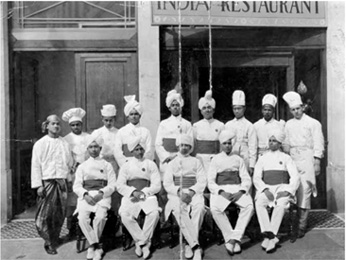

In 1870, over 90 per cent of the tea drunk in Britain came from China, and the proportion was even higher in most other tea-drinking countries. But the producers of Indian tea were at last ready to challenge the Chinese and, in the 1880s, they began a vigorous global marketing campaign at the various colonial exhibitions. In Britain, the public enthusiastically accepted free samples of cups of Indian tea as well as the teaspoons, which disappeared inside their pockets at an alarming rate. Teapots also had a low survival rate, with only ten out of 180 surviving the London Health Exhibition of 1888. Indian khidmutgars, in colourful uniforms, were employed at the Paris exhibition of 1889 to create an exotic atmosphere, and in America they travelled the country selling tea at state fairs. At the Garden Palace Exhibition in Melbourne in 1880 Indian teas carried off most of the prizes.33 In Australia, the campaign was carried on virtually single-handedly by James Inglis, whose brother was a Calcutta tea merchant. Continental Europeans and Americans were fairly unresponsive, but the British and Australians began to develop a preference for the fermented black teas of India rather than the unfermented green of China.

In Britain and Australia, the working class’s passion for strong black Indian tea was encouraged by inventive wholesalers who found ways of selling Indian tea at cheaper rates than Chinese teas. Thomas Lipton innovatively purchased his tea leaves in bulk, directly from India (and Ceylon where the tea plantations were first established in the 1880s). At his one hundred shops around Britain, he was able to sell tea for about a quarter of the price charged by ordinary grocers. By 1909, tea was associated in British minds with India to such an extent that it was worth Lipton’s while to employ an Indian to stand in front of one of his London cafés as an advertisement. The Indian in question was ‘an undergraduate’, driven through poverty to find whatever employment he could. By 1900, only 10 per cent (and falling) of the tea consumed in Britain came from China while 50 per cent came from India and 33 from Ceylon.34

Although tea was strongly associated with India in British and Australian minds, Indians still did not drink it themselves. In the cities, to be sure, ‘gentlemen as have frequent intercourse with the “Sahib Logue” (English gentry) . . . [had] acquire[d] a taste for this delightful beverage’ and Gandhi acknowledged that a few westernised Indians now drank a cup or two of tea for breakfast. But, he continued, ‘the drinking of tea and coffee by the so-called educated Indians, chiefly due to British rule, may be passed over with the briefest notice’.35 For the majority of the Indian population, tea was far too expensive a foreign habit. All the paraphernalia of tea drinking – teapots, china cups and saucers, sugar bowls and milk jugs – were too costly for most people. Even in Assam, families working in the tea industry would not have drunk tea at home.36 In his survey of the economic products of India, George Watt observed in 1889 that ‘while India has not only challenged but beaten China, during the past 30 years, no progress has been made in teaching the native population of India the value of tea’.37 In 1901, the Indian Tea Association woke up to the fact that their largest market was sitting right on their doorstep and they extended their marketing campaign to the subcontinent. This extraordinary venture, one of the first of its kind in India, used methods which were new to the region, and to advertising in general.

The Tea Association began by employing a superintendent and two ‘smart European travellers’ to visit grocers. Their task was to persuade them to stock more tea on their shelves. Just before the outbreak of the First World War, at a dinner party given by the Maharaja of Udaipur, the Reverend St Clair Weeden was surprised to find himself sitting next to one such ‘traveller’, ‘an amusing Irishman, who had been going about India for the last five years, selling cheap packets of Lipton’s teas, to which the natives are taking very kindly’.38 These salesmen also arranged for the delivery of liquid tea to offices, and in 1903 the committee in charge of tea propaganda in the south noted that they received complaints ‘should there be any failure in the daily supply at the various Government and mercantile offices’.39 Nevertheless, marketing tea in India was a dispiriting project. In 1904, it was reported that even after three years of hard work there was little to indicate ‘the existence of a proper tea market in India’, and every year from 1901 to 1914, there were complaints that ‘increasing the consumption of tea in India is undoubtedly the most difficult branch of the work’.40

During the First World War the campaign began to gain momentum. Tea stalls had been set up at factories, coal mines and cotton mills where thirsty labourers provided a captive market. The war made factory and mill owners more conscious of the need to keep their workers happy, and they were persuaded to allow time off for tea breaks. The Tea Association hoped that ‘having learnt to drink tea at his work [the employee] will take the habit with him to his home, and so accustom his family and friends to tea’. By 1919, the tea canteen was firmly established as ‘an important element in an industrial concern’.41 Thus, tea entered Indian life as an integral part of the modern industrial world that began to encroach on India in the twentieth century.

The railways were another example of the arrival of the industrial world in India, and the Tea Association transformed them into vehicles for global capitalism. They equipped small contractors with kettles and cups and packets of tea and set them to work at the major railway junctions in the Punjab, the North-West Frontier and Bengal. The cry of ‘Chai! Gurram, gurram chai!’ (‘Tea! Hot, hot tea!’) mingled with the shouts of the pani (water) carriers calling out ‘Hindu pani!’, ‘Muslim pani!’.42 Muslim rail passengers were less bothered by the caste restrictions which hindered Hindus from accepting food or even water from anyone of a lower caste, and they took to tea with enthusiasm. Although the European instructors took great care to guide the tea vendors in the correct way of making a cup of tea, they often ignored this advice and made tea their own way, with plenty of milk and lots of sugar. This milky, intensely sweet mixture appealed to north Indians who like buttermilk and yogurt drinks (lassis). It was affordable and went well with the chapattis, spicy dry potatoes and biscuits sold by other station vendors, running alongside the carriage windows as the trains pulled into the station. Eventually, tea stalls at the railway stations catered to communal sensibilities and were divided into Muslim and Hindu sections.43

In the south, the tea marketers had to compete with coffee. Arab traders had begun cultivating small plots of coffee in the western hills by the seventeenth century, and coffee plantations were established in Ceylon in the 1830s. Thus, coffee had a head start on tea. Even today the coffee wallahs begin to outnumber the chai wallahs as trains pass south. But in the 1930s the Tea Association proudly pronounced the railway campaign a success. They congratulated themselves on the fact that ‘a better cup of tea could in general be had at the platform tea stalls than in the first class restaurant cars on the trains’.44 The chai wallah is still the first thing a passenger hears on waking up in a train in northern India as he marches through the carriages, a metal kettle swinging in one hand and glasses in the other, calling out ‘chai-chai-chai’.

Another branch of the campaign set up tea shops in India’s large towns and ports. These tea shops had a satisfactory snowball effect. ‘Immediately the tea shop was established on a selling basis, shops in the neighbourhood – which did not normally sell tea – commenced to do so, and the areas surrounding the tea shops were infested with tea hawkers who undersold our shops to such an extent that finally they had to be closed down.’ This was seen as progress. The only matter for concern was that the tea hawkers tended to flavour the tea with spices. The Indians demonstrated their characteristic tendency to take a new foodstuff and transform it by applying Indian methods of preparation. This was not a problem in itself, but in spiced tea they tended to use fewer tea leaves. For a campaign that counted every cup of tea and every ounce of tea leaf sold this was a move in the wrong direction. ‘Steps are now being taken to have this remedied,’ reported one campaigner. ‘It is in the Cawnpore Mill area where we have found this so-called “spiced tea” . . . and we are now employing our own hawkers in that district who sell well-made liquid tea in direct competition to the unsavoury and badly prepared decoction known as “spiced tea”.’45

Tea shops only reached a certain type of clientele. A series of campaigns therefore set about taking tea directly into the Indian home, particularly to women who would not have visited tea shops. An army of tea demonstrators was employed to march on the large towns and cities. An area of each town was chosen, and for four months the tea campaigners visited every house, street by street, every day at the same time, except on Sundays. ‘As far as possible we aim at brewing the tea inside the house so as to teach the householder the correct method of preparation,’ one demonstrator explained. The campaigners expected to face hostility. Certain Muslim quarters in Lahore remained impervious, but they were surprised to find that ‘even in the more orthodox and conservative places quite a number of households will allow our staff to demonstrate right inside the house’. The ladies would peek from behind purdah screens at the brewing demonstration, held in the courtyard. In very high-class purdah areas, the committee employed lady demonstrators. In rigidly orthodox Hindu towns, the Brahmans ‘quite definitely refused to accept tea from our demonstrators, in spite of their protestations that they and the Sub-Inspectors were just as good Brahmans as themselves’. In Trichonopoly the demonstrators circumvented this problem by persuading the priests at the Srirangam temple to allow them to distribute cups of tea in the temple precincts.

Having established a habit of making tea at the same time every day in many households in the cities, the demonstrators moved out into smaller provincial towns and this is when they met the Nagarathars of Karaikudi, who started this chapter.46 The special unit’s triumph with the Nagarathars is an indication of the extent to which tea drinking was beginning to penetrate urban India. In the Punjab, the older generation began to complain about young people drinking tea rather than the milk or buttermilk which they thought much healthier.47

Syed Rasul left the town of Mirpur (now in Pakistan) in 1930 or 1932: ‘The first time I had a cup of tea was when I came to Bombay. In the village we used to drink only milk, and water. Only if somebody was ill they would give . . . something like a cup of tea – it was like a medicine.’48 Despite the money and effort channelled into the tea-marketing campaigns, some corners of the country were still untouched. To address this the ‘packing factory scheme’ was started in 1931. Lorries, and in Bengal houseboats, were sent to the local markets where ‘thousands of villagers . . . congregate’ where they distributed cups of tea. The demonstrators reported that ‘at first we had to use much persuasion to induce the ryot to accept a cup of tea’. But the cinema performances which accompanied the tea distribution, helped to make it more popular. The women, who were provided with a special enclosure, particularly liked the films. They were observed ‘sharing [their] tea with children of all ages, even infants in arms’. By the end of 1936, Indian villagers had become so accustomed to tea that in one year the demonstrators were able to give away 26 million cups of it with ease.49

During the Second World War, the marketing campaign was temporarily closed down and the Indian Tea Association concentrated their efforts on the army. Special tea vans were set up to supply the troops. Several of these were even sent overseas with Indian troops fighting in the European arena. The vans were equipped with radio sets, gramophone records of Indian songs, and letter writers so that the soldiers could keep in touch with their families at home while simultaneously acquiring the tea-drinking habit. An enthusiastic army officer, who had been a tea planter before the war, wrote to the Tea Association to commend their efforts: ‘During a 3 days march, under trying climatic conditions, [your tea] van served over 10,000 cups of good tea to Officers and other ranks of this Unit. Quite apart from the value of the drink on that and other occasions, which was much appreciated, the propaganda value must be incalculable. Our sepoys are now definitely “tea conscious” and in post-war days this tea-drinking habit will be carried into many villages throughout India.’

Once the Japanese had brought the war close to India, tea vans serviced air-raid protection workers in the cities of Calcutta, Howrah and Madras, and traumatised survivors of the Malayan and Burmese rout were supplied with hot, comforting cups of tea. In Bombay, the tea car dealing with embarking and disembarking troops was able to proselytise tea among the Americans. They ‘regarded tea with considerable suspicion at first . . . [but] on persuasion [they] were induced to take it without milk’.50 Indeed, tea became the British panacea for all ills during the war. The author of a handbook on canteens explained in 1941 that ‘Psychologically tea breeds contentment. It is so bound up with fellowship and the home and pleasant memories that its results are also magic.’51

By 1945, even the homeless living on the streets of Calcutta were drinking tea, and the milkman would stop on his rounds to supply them with a drop of milk to add to their tea.52 Nevertheless, the Tea Association was not entirely satisfied. In 1955, the per capita consumption in India was still only about half a pound, compared with nearly ten pounds in Britain. The marketing machine was restarted.53 But it is in the nature of a marketing campaign to argue that people can always drink, or eat, more of its product. In fact, the relentless campaigning of the tea demonstrators, tea shops, railway stalls and military tea vans, had already significantly changed Indian drinking habits. They were so successful at introducing tea into India that at the end of the twentieth century, the Indian population, which had barely touched a drop of tea in 1900, were drinking almost 70 per cent of their huge crop of 715,000 tons per year.54

Tea is now a normal part of everyday life in India. The tea shop is a feature of every city, town and village. Often they are nothing more than ‘a tarpaulin or piece of bamboo matting stretched over four posts . . . [with] a table, a couple of rickety benches and a portable stove with the kettle permanently on’.55 Men gather round, standing or squatting on their haunches, sipping the hot tea. The tiny earthenware cups, in which the drink is served, lie smashed around the stalls. Everybody drinks tea in India nowadays, even the sadhus (holy men), the most orthodox of Brahmans and the very poor, who use it as a way of staving off hunger.56

Admittedly, much of the tea which is sold in India would not be approved of by the Tea Association inspectors. It is invariably milky and sweet. This makes it popular with the calorie-starved labourer. A wizened, but sinewy, bicycle-rickshaw driver from Cochin once informed me that tea was the basis of his strength. This surprised me at the time, but one cup of this milky sweet tea can contain as many as forty calories, enough to give a tired rickshaw driver a quick burst of energy.57 Indian tea-stall owners flavour their tea in a variety of thoroughly un-British ways. In Calcutta, the speciality of one stall is lemon tea flavoured with sugar ‘and a pinch of bitnoon, a dark, pungent salt’.58 The poor in villages also flavour their tea with salt as it is easier to ask for a pinch of salt from a neighbour than it is to ask for more expensive sugar.59

The tea stalls also sell that ‘unsavoury and badly prepared decoction known as “spiced tea” which the Tea Association inspector discovered being served in the Cawnpore mill district in the 1930s.60 The tea leaves are mixed with water, milk, sugar, a handful of cardamoms, some sticks of cinnamon, sometimes black pepper, and simmered for hours. The result is faintly smoky, bittersweet and thick, with an aroma reminiscent of Christmas puddings. Indians have been flavouring milky drinks with spices for centuries. Ancient Ayurvedic medical texts recommend boiling water mixed together with sour curds, sugar, honey, ghee, black pepper and cardamoms, for fevers, catarrh and colds. In the Punjab, buttermilk is often mixed together with cumin, pepper or chilli, and khir, a sweet milk-rice which uses dried fruits and aromatic spices such as cardamom, is a favourite dish throughout India.61 Spiced tea is simply a variation on these drinks. Sold as chai, spiced tea is now becoming fashionable in American and British coffee shops. It is marketed as an exotic oriental drink and yet it is in many ways the product of a British campaign to persuade Indians to drink tea.

The spread of tea drinking in India has had a surprising impact on Indian society. In British hands the practices surrounding the sale of tea appear to have had a rather negative effect. The British are often accused of worsening relations between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, due to the Raj policy of divide and rule. The rise of communalism in India during the nineteenth century is a complex and divisive subject. The British played their part in this, often inadvertently. When the British were responsible for providing food for their Indian subjects, they were usually scrupulous about respecting the caste and communal restrictions surrounding food preparation. At railway stations throughout India, Hindu and Muslim passengers were supplied with water by separate water carriers.62 The same principle was applied to tea at the railway stations, and tea stalls were often divided into Muslim and Hindu sections. The tea vans which accompanied the troops abroad served Muslims from one window, Hindus from another. The overall effect of these apparently benign acts of cultural accommodation was to reinforce the divisions between the different communities, thus creating the conditions in which communalism could thrive.

While tea in British hands could become an instrument of communal separation, in Indian hands it has often improved intercommunal relations. For many Indians tea, as a foreign foodstuff, lies outside Ayurvedic classifications and is therefore free from the burden of purity associations. The neutrality of tea makes it easier to share with impunity with members of a caste normally rejected as eating or drinking partners.

Prakash Tandon observed the breakdown of caste restrictions within his own Punjabi Khatri family as British goods began to infiltrate the household. Tandon’s father was a member of the educated Indian middle classes. Having graduated as a civil engineer he ‘joined the irrigation department of the Punjab government’ in 1898. Tandon’s mother came from an orthodox Hindu family. She was a strict vegetarian all her life, ‘consequently her food was cooked separately from ours, and while she did not mind onions entering the kitchen, meat and fish had to be kept and prepared outside. On nights when we children wanted to snuggle into her bed and be kissed by her, we would share her food. She did not say no, but we knew she did not like us smelling of meat.’ His mother was strict about intercommunal dining and when she accepted a glass of water from a Muslim household it was always with the assurance that both the glass and the water had been fetched from a nearby Hindu family.

In contrast to his wife, Tandon’s father was uninterested in the preservation of caste and community divisions and he would bring his Muslim colleagues home from work to eat at their house. This posed his mother with a problem. She was reluctant to serve the guests on the metal plates and mugs that the family used as these would be indelibly polluted. ‘Interestingly, this problem was solved in our home, as in many other homes where a similar change was at work, by the introduction of chinaware. Our women . . . willingly shared china plates, cups and saucers. These were somehow considered uncontaminable. Their gleaming white, smooth surface, from which grease slipped so easily, somehow immunised them from contamination. My mother would not at first use the chinaware herself and reserved it for the menfolk and for Muslim, Christian and English guests, but she soon began to weaken.’ Once she had made these concessions his mother was prepared to accept unpeeled fruit from non-Hindus. ‘Then followed the acceptance of tea and manufactured biscuits and the English bottled lime cordial.’ These British packaged goods appeared neutral foods which were less contaminating. However, his mother never relaxed her guard to the point where she was prepared actually to eat with her husband’s Muslim and English colleagues.63 In general, women were far less prepared to abandon caste restrictions than men. For them, being made outcaste meant the probable loss of kin and friendship networks. Men had much to gain from free and easy social exchanges with their colleagues; women had everything to lose. Tea, and its associated products such as cordials and biscuits, as well as chinaware, all assisted them in accommodating to the breakdown of traditional social divisions.

Tea has also played a role in encouraging intercaste and community socialising in less westernised circles. In the 1950s, an anthropologist came across old men in a Rajasthani village lamenting the fact that caste rules were regularly broken without consequences. ‘A visible sign of the demoralised state of society was the willingness of young Brahmans, Rajputs and Banias to sit with their social inferiors, drinking tea in public tea-shops.’ Shri Shankar Lal, a Brahman from the village, freely admitted that he often took tea with men from all castes. If one village group manages to raise its status, the standing of another inevitably declines. This knock-on effect in village hierarchies means that there is a strong tendency towards inertia in the system.64 But tea shops provide the men with a separate, compartmentalised space where they can form intercaste and intercommunal friendships and alliances without necessarily affecting their traditional standing in the village.

There are, of course, limits to the willingness of villagers to bend caste rules. Although Shri Shankar Lal was happy to drink tea with men from all castes he did not extend this accommodation to the ‘lowest sudras’. All the men in his village admitted that they would suffer immense ‘internal distress . . . at the thought of having to sit and eat and drink with members of the lowest “untouchable” castes’.65 Although the legal position of the untouchable castes has improved since independence, old prejudices are difficult to overcome.66 As one Punjabi villager remarked, ‘if throughout your life you have been taught to regard someone as filthy, a mere statute is not going to make you want to sit down and eat with him all of a sudden’.67 Tea in India is often served in small earthenware cups which are smashed on the floor once they have been used. This ensures that no one is polluted by drinking from a vessel made impure by the saliva of another person. Earthenware cups are standard in urban areas where the caste status of the customers is unknown to the stall owner. But in the villages these earthenware cups are often reserved for the untouchables, while the other customers are given their tea in glasses. In one village in northern India an anthropologist came across untouchables asserting their modern rights over the way they were served a modern drink. He was told that, these days, the untouchables throw away tea given to them in a clay vessel, demand a glass and threaten the owner with litigation.68

The spread of tea by means of modern marketing and advertising techniques was just one of the ways in which technology and industrialisation were beginning to change Indians’ eating habits. The Muslims of India have always had a strong tradition of eating out, or buying food in from bazaar cooks, but high-caste Hindus have traditionally avoided anything other than home-cooked food. But the changing political and economic circumstances of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries meant that increasing numbers of Hindus were confronted with the need to eat outside their own homes. More and more Indians travelled around the country on business. Single men left the villages to seek work in the urban areas. Crammed together on buses and trains it was hard to maintain the principle of separate dining arrangements, although stations did provide separate Hindu and Muslim restaurants. In 1939, a group of educated merchants told an American visitor to India that ‘trains and motors have put an end to all this affair of special food and separate meals’.69 At the Victoria rail terminus in Bombay there were three restaurants: Divadkar’s for vegetarian Hindus, Karim’s for the non-vegetarian Muslims, and Brandon’s, for the British. For inquisitive young Hindus, Divadkar’s was dull and predictable. One Brahman from an orthodox Bombay family remembered his nonconformist uncle taking him to the Muslim restaurant to try out the mutton biryani.70

Many Indian businessmen seem to have compartmentalised their working lives in the cities and towns from their home lives in the villages. While they might have rigidly observed rituals of purity at home many businessmen tended to abandon them when travelling, even though restaurants and hotels in the cities employed Brahman chefs which provided careful Brahmans with a pure and safe place to eat.71 One anthropologist was ‘asked by informants not to disclose in the village how they eat when in town’. The further away from home they travelled, and the more anonymous the place, the less fastidious they became. A Brahman from a small village might not have eaten food cooked by a Muslim in the closest town, ‘but in Delhi he might’.72

Some even sought out these opportunities, and used the railway restaurants and hotel dining rooms as clandestine spaces for experimentation. While he was staying in Nagpur (in Maharashtra) in the 1930s, Prakash Tandon observed ‘dhoti-clad, vegetarian-looking small business men’ shuffling into the railway station restaurant. He discovered they had come ‘to indulge in secret vices. Some drank beer and whisky but most came to eat savoury omelettes with potato wafers, or even mutton chops. The darkened verandah of the station restaurant provided a safe place for indulging these newly acquired tastes that would have horrified their women at home.’

Single men looking for work in the new industrial and commercial spaces, such as the mills, factories and offices, arrived in the cities in their droves. At first, special eating houses were set up which catered for men from a particular village or from a particular caste. But the new pressures and conditions of life created by capitalist enterprise made it increasingly difficult to observe the rules regulating food consumption. As one Punjabi villager commented, in Delhi ‘I never used to bother much about caste, in fact in the town it is not always even possible to know for sure what caste a man really comes from’.73 Gradually, a new civic culture developed in India’s cities which inhibited the open expression of caste prejudice.74

Changes in eating habits and the growth of eating houses was particularly pronounced in Bombay, which at the beginning of the twentieth century was the centre of India’s textile and iron and steel industry.

In the 1890s, the working men of Bombay were provided with tea and snacks by Parsee immigrants from Iran who set up small tea stalls on street corners, selling soda water, cups of tea and biscuits, fried eggs, omelettes and small daily necessities such as toothpaste, soap and loose cigarettes. When Bombay’s Improvement Trust embarked on a programme of urban renewal after the plague epidemic of 1896, new roads were cut through the most congested areas of the city. The Iranian tea-stall owners moved into the shops which were created as a result and ‘Irani’ cafés became a Bombay institution. They had a particular interior aesthetic and were usually furnished with white marble-topped tables, spindly-legged wooden chairs and full-length mirrors. They were often plastered with officious and habitually ignored little notices, instructing the customers not to comb their hair in front of the mirrors or forbidding them from discussing gambling. Labourers and office workers of all castes and communities came to the Iranis to drink tea and snack on English buns, cream cakes and biscuits, and potato omelettes. They also included on their menus Parsee specialities such as dhansak, green chutney and patra fish, and a hard Iranian bread known as brun-maska, so crusty that it needed to be dunked in tea before it could be eaten. Newspapers were provided, divided up into separate pages so that as many customers as possible could simultaneously read the same paper. At first the café owners respected communal sensibilities and Hindu customers were served their tea in green cups, Muslims in pink, Parsees and Christians in other colours. But this practice gradually died away.75

During the 1920s and 30s the number of eating houses catering to middle-class office workers increased. These were functional places where the principle was to eat as quickly as possible. At the Madhavashram near the Girgaum Police Court, the customers had to bolt their food, as the next line of diners stood impatiently behind their chairs.76 Most cafés, eating houses, street stalls and bazaar cooks provided food for hungry working people and travellers. Very few Indians went to a restaurant simply to eat good food in a pleasant atmosphere. This was reflected in the simple decor of the majority of Indian eating houses. There are still many such places in Bombay where the food is eaten from plain metal thalis at smeary Formica-topped tables, and the kitchens beyond the swing doors look as though they could do with a thorough scrub. Indeed, it was partly the unhygienic reputation of eating houses which prevented the spread of restaurant-going among India’s population. Other hindrances included the reluctance of women to dine out in public, although some Irani cafés encouraged families to patronise them by providing special family cabins which meant that the women felt less exposed. Dietary preferences, rules and restrictions also meant that most Indians would have visited a restaurant which served the sort of food which they ate at home. And given that home-cooked meals, even today, are still generally tastier than anything served in a restaurant, the idea of a meal as a leisure experience did not catch on.

Today, office workers in Bombay can have a home-cooked lunch delivered to their workplace. This service is supposed to have been started by an Englishman who arranged for his bearer to bring lunch to the office. The idea caught on and developed into a lunch-delivery pool which now employs about two thousand dabba wallahs, or tiffin carriers, to deliver over 100,000 lunches every day. Early in the morning housewives all over Bombay city and its suburbs start preparing their husband’s lunch. Bachelors and working women rely on contracted cooks who supply home-style lunches. By ten o’clock the meals have been dished into three separate aluminium containers: one for rice, one for a meat or a vegetable dish, and the other for chutneys or bread. The three containers are then clasped together and loaded into a tin outer case which keeps the food warm and prevents it from spilling. This is the dabba or tiffin box. This is handed over to the dabba wallah, who calls at each private house at the same time every day and then hurries to pass his tiffin boxes on to the next dabba wallah in a long relay chain of carriers until each box reaches its designated office worker in time for lunch. Every box has a series of symbols painted on it which tell the wallahs where it needs to go at each stage of its journey. A yellow stroke signifies Victoria terminus, a black circle the Times of India offices, and so forth. After lunch the wallah returns to collect up the cases and they travel along the same route in reverse until they are delivered to the housewife to wash up in preparation for the next day.

The dabba wallahs’ job is a hard one. The trays, which they carry on their heads, can weigh as much as fifty kilograms when crammed with tiffin boxes. They have to struggle on and off the overcrowded suburban trains and bicycle through the heavy traffic of the Bombay streets, and they are always in a hurry to get the dabbas to their destination on time. It is an amazingly complex system yet it is very rare for the vegetarian Hindu to open up his tiffin box to discover a meat curry. The only real threat to the proper delivery of the lunch are the dabba thieves who occasionally make off with a selection of assorted lunches. Although a Muslim non-vegetarian meal may be transported alongside a vegetarian Hindu one, the system ensures that clerical workers need risk neither their health nor their caste purity, at the reasonable price of about US$3 a month.77

Thirsty office workers in Bombay can choose from a range of drinks. These days many people will drink a bottle of soda with their lunch. This was another British introduction to India. The British began manufacturing soda water at a factory in Farrukhabad in the 1830s and the Indian population soon grew to like it. As a child growing up in the small Punjabi town of Gujrat, Prakash Tandon was impressed by the rows of ‘coloured aerated drinks’ for sale in the soda-water shop. This particular shopkeeper offered fifty different flavours, in a variety of garish colours, including a mix of beer and pink-rose sherbet, which he made up specially for ‘a local barrister who had been to England’.78 Many of the Iranians in Bombay started off by selling sodas, as well as tea, on the street corners. But new drinks have not entirely ousted more traditional Indian fruit juices. Bombay street corners are dotted with fruit-juice sellers offering freshly squeezed orange and pineapple juice, and the Bombay chain of Badshah Cold Drink Houses sells grape and watermelon juices. Every café and eating house supplies the refreshing and rehydrating nimbu pani (lime water), made with sweet lime juice mixed with salt, pepper and sugar. And Indians still retain their taste for milky drinks such as Persian faloodas and lassis of yogurt whipped together with iced water and flavoured with either sugar or salt. Nevertheless, virtually every office worker in Bombay will finish off his or her lunch with a cup of tea: a symbol of the way eating and drinking habits have changed in an ever more industrial and modern India.

These are two ways to make that ‘unsavoury . . . decoction’, spiced tea, which the tea hawkers sold in the Cawnpore Mill area in the 1930s to the disapproval of the Tea Association campaigners. (See overleaf for the second method.)

4 tablespoons ground ginger

2 tablespoons whole black peppercorns

2 tablespoons green cardamom seeds

1 tablespoon whole cloves

pot of tea

milk and sugar, to taste

Grind the spices in a clean coffee grinder. Store the powder in an air-tight container and add ½ teaspoon to a pot of tea. Serve with milk and sugar.

950ml water

16 whole cardamoms, slightly crushed

2 cinnamon sticks

120ml milk

75g strong black tea leaves

honey or sugar to taste

Bring the water to a boil in a large pan and add the cardamoms and cinnamon sticks. Simmer for 15–20 minutes.

In a separate pan bring the milk to just below boiling point and set aside.

Add the tea leaves to the simmering water and then remove from the heat. Steep for 3–5 minutes.

Strain the leaves and spices and add the milk and honey or sugar to sweeten. Serve immediately. Serves 6.

These days lassis are made with yogurt. Bombay lassis are often made with buffalo-milk yogurt which is very good for this purpose.

200ml yogurt

50ml iced water (or chips of ice)

sugar or honey to taste (about 2 tablespoons)

Optional additions

⅛ teaspoon cardamom powder

2 teaspoons ground almonds or pistachios

salt and ½ teaspoon of garam masala to make a sour lassi

Put the ingredients in a blender and blend until the contents become foamy. Serves 2.

Originally, Punjabis made their lassis with the buttermilk which was a by-product of manufacturing ghee.

250ml mango purée (or use any other fruit purée which takes your fancy)

450ml buttermilk (if you prefer you can use yogurt)

1 teaspoon lemon juice

½ teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon honey

pinch of nutmeg

10 crushed ice cubes

Put the ingredients in a blender and blend until the contents become foamy. Serves 3–4.

This refreshing drink is served all over India and is a very good way to rehydrate the body after a day in the heat.

juice of 3–4 limes

2 teaspoons of sugar

pinch of salt

a little freshly ground black pepper

200ml chilled water

Mix the lime juice, sugar, salt and pepper with the water and pour over ice cubes in a chilled glass. Serves 1.