Visual Culture, Classical Poetry, and Linked Verse

Waka (classical poetry) reached its zenith as a genre in the Heian (794–1185) and Kamakura (1185–1333) periods and continued to be widely practiced even as its popularity waned in the Muromachi (1392–1573) and Edo (1600–1867) periods. In the Muromachi period, waka was finally superseded by renga (classical linked verse), which became the most popular late medieval poetic form. Renga, in turn, was surpassed by haikai (popular linked verse), which came to the fore in the seventeenth century. The seasonal associations developed by waka were inherited and disseminated by both renga and haikai, but in contrast to renga, which maintained the elegant diction and traditional topics of waka, haikai also embraced popular culture and non-classical diction, including Chinese.

All three poetic forms had a huge impact on visual and material culture. Waka was critical to the genres of Heian-period four-season paintings, twelve-month paintings, and famous-place paintings—not to mention the scroll paintings (emaki) that depict Heian court tales. Eventually, the seasonal and natural associations developed by waka were used in the designs for women’s clothing, ceramics, lacquerware, furniture, tea ceremony utensils, and flower arrangement—to mention only the most obvious. Renga carried on the tradition of waka, refining its topics and diction even further and bringing it into contact with other late medieval genres such as noh.

Wearing the Seasons

The manner in which the seasonal associations of waka, particularly those of flowers and plants, permeated Heian aristocratic culture is perhaps most dramatically demonstrated in the design and colors of the woman’s multilayered kimono now referred to as the juni hitoe (literally, “twelve-layered dress”) (figure 6). Each layer (kasane) of the robe had a specific color combination (irome), appropriate for each season:1

SPRING

Crimson plum (kōbai) | Bright red surface, dark reddish-purple interior |

Cherry blossom (sakura) | White surface, pinkish-maroon interior |

Yellow kerria (yamabuki) | Light tan surface, yellow interior |

Wisteria (fuji) | Light lavender surface, dark green interior |

SUMMER

Deutzia flower (unohana) | White surface, green interior |

Mandarin-orange blossom (hanatachibana) | Withered leaf-patterned surface, green interior |

Iris (kakitsubata) | Scallion-patterned surface, crimson interior |

Sweet flag (shōbu) | Scallion-patterned light green surface, purple interior |

Pink (nadeshiko) | Crimson surface, light lavender interior |

AUTUMN

Withered leaf (kuchiba) | Russet surface, yellow interior |

Bush clover (hagi) | Dark red surface, green interior |

Yellow valerian (ominaeshi) | Yellow surface, dark green interior |

Bright foliage (momiji) | Reddish-brown surface, brown interior |

Fading chrysanthemum (utsuroigiku) | Light lavender surface, blue-green interior |

WINTER

White chrysanthemum (shiragiku) | White surface, green or dark red interior |

Withered field (kareno) | Yellow surface, light green or white interior |

Ice (koori) | Light gray surface, white interior |

TRANS-SEASONAL

Grape (ebi) | Dark reddish purple surface, dark green interior |

MULTILAYERED HEIAN-PERIOD KIMONO

In this detail from the Picture Scroll of the Thirty-six Poetic Geniuses (Sanjū rokkasen emaki [Satake-bon variant]), Kodai no Kimi (Koōkimi, mid-Heian period), one of the female poetic geniuses (kasen), is portrayed in a Chinese robe (karaginu) with multilayered unlined kimono (jūni hitoe) and a detachable skirt (mo). The layers of the kimono and the colors that distinguish them are visible in the right sleeve and in the hem. The poems in the scroll were selected by Fujiwara no Kintō (966–1041). The paintings are attributed to Fujiwara no Nobuzane (1176–ca.1265) and the calligraphy to Fujiwara no Yoshitsune (1169–1206). (Color on paper; 14 x 23.3 inches. Courtesy of Museum Yamato Bunkakan, Nara)

Almost all the kasane names derive from seasonal plants that are also prominent in waka. Each name refers to a color combination that was used not only in clothing but also in decorative paper for letters, poems, and picture scrolls.2

With only a few exceptions (such as “grape,” which could be worn year-round), each kasane color combination represented a specific season and sometimes a specific month. In this fashion, Heian aristocrats brought waka-related “nature” into their everyday lives. At the beginning of spring, when the crimson plum tree blossomed, it was customary for an aristocratic woman to wear a “crimson plum” kasane robe, with bright red on the outside and dark reddish-purple on the inside, and to write letters on paper decorated with the “crimson plum” color combination. Likewise, when autumn arrived and the tree leaves withered and scattered, an aristocratic woman was expected to wear a robe with the “withered leaf” color combination of faded red or russet on the outside and yellow on the inside. In the section “Susamajiki mono” (Awful Things) in Makura no sōshi (The Pillow Book, ca. 1000), Sei Shōnagon lists the following: “Dogs howling at noon, a fishing weir in spring, and a crimson plum robe in the Third and Fourth Months.” Dogs were expected to howl at night, the weir was used to catch fish in the winter, and the “crimson plum” robe was supposed to be worn when the crimson plum tree was in bloom, which was early spring, in the First and Second Months. What was “awful” was wearing it in late spring (Third Month) or in early summer (Fourth Month).

The impact of waka on women’s high fashion in the Edo period is also evident in the design of the kosode (now referred to as the kimono). The kosode (literally, “small sleeve”), which is a form of wearable art, has a simple construction based on straight lines: sleeve panels are sewn onto the body panels to produce a flat surface like a painter’s canvas. Edo-period kosode, worn by upper-level samurai and wealthy urban commoner women, are decorated with different designs—auspicious motifs, classical literary subjects, famous places in waka, and so forth—but the dominant design elements are seasonal flowers, trees, and other plants, based largely on the associations found in classical poetry. (The same was true of the kimono worn by high-ranking courtesans [oiran] in the pleasure quarters.) Typical spring designs are the first blossoms of the plum, willow, camellia (tsubaki), cherry tree in bloom, and waves of wisteria blossoms. Noted autumn designs are chrysanthemum in the hedge, Musashi Field (covered with autumn grasses and flowers), and the Tatsuta River (bright foliage).

One popular technique was to embed a waka in the form of scattered writing (chirashi-gaki) in the design of a kosode. Often only several characters were sprinkled across the robe, leaving the rest of the poem to be recalled by the discerning viewer. A few of the graphs were clear, but the others were buried in the design, as in reed hand (ashide) writing, in which the calligraphy is part of the image. A typical example is furisode (literally, “swinging sleeve”), or long-sleeved kimono, from the mid-Edo period that is decorated with yellow kerria on waves (figure 7). The scattered graphs refer to Fujiwara no Shunzei’s (1114–1204) poem in the Shinshūshū (New Collection of Gleanings, 1364), the nineteenth imperial waka anthology: “The bottom of the Tama River at Ide, reflecting the image above, is so clear that the flowers of the yellow kerria add layer upon layer” (Kage utsusu Ide no Tamagawa soko kiyomi yae ni yaesou yamabuki no hana [Spring 2, no. 177]). In the Nara period (710–784), Tachibana no Moroe (684–757) is thought to have planted yamabuki on the banks of the Tama River in Ide (in present-day Kyoto Prefecture), and the Tama River subsequently became famous as an utamakura (poetic place) on which many classical poems were based. In the twelve-layered robe of the Heian period, the color combination, named after a flower and its color, reflected the phase of a season. But in the kosode of the Edo period, the design referenced not only a specific season, but a specific poem and place. In this way, the kosode designs enhanced the beauty of the wearer and expressed her taste and education, particularly her cultural sensitivity to the seasons.

YOUNG WOMAN’S KIMONO WITH YELLOW KERRIA

This white figured-satin, long-sleeved dress for a young woman (furisode) from the mid-Edo period is embroidered with a design of golden-yellow waves and yellow kerria (yamabuki), interwoven with fragmentary calligraphy of Fujiwara no Shunzei’s noted poem on the yamabuki. (Courtesy of the Matsuzakaya Collection, Nagoya)

The colors of the Heian kasane robe and the designs of the Edo kosode could also anticipate the next season. This was particularly true for winter, when it was not unusual to don spring color combinations that signaled that the wearer was waiting for spring, much as the last winter poems in the Kokinshū (Collection of Japanese Poems Old and New, ca. 905) anticipate spring by “mistaking” the white snowflakes for cherry blossoms. Similarly, the Edo-period kosode meant for summer wear were marked by two major characteristics: a sense of coolness (light colors and light fabric), and autumn motifs such as morning glory, dew, bush clover, and yellow valerian. By wearing autumn designs in the summer, a woman showed that she was waiting for the coolness of autumn. The wearer of a twelve-layered kasane robe could also show appreciation for the autumn that was ending by choosing, for example, the “fading chrysanthemum” (utsuroigiku) combination of light lavender on the outside and blue-green on the inside. When the white chrysanthemum passes its peak, its petals are tinged with crimson—an aspect alluded to in the dark red interior of the “white chrysanthemum” color combination, which is worn in winter and thus expresses the wearer’s regard for the autumn that has just passed.

Painting the Seasons

In the Heian period, aristocrats not only “wore” the seasons, but were surrounded by waka-based seasonal references inside their palace-style (shinden-zukuri) residences. As Takeda Tsuneo has argued, one of the most salient features of the Yamato-e (Japanese-style painting) that emerged in the mid-Heian period was an emphasis on the four seasons, specifically in the three major painting genres: four-season painting (shiki-e), twelve-month painting (tsukinami-e), and famous-place painting (meisho-e).3 The shiki-e presents four scenes, one for each season, while the tsukinami-e depicts one scene for each of the twelve months, and the meisho-e portrays famous places with seasonal associations drawn from waka, such as Kasuga Field and the Tatsuta River. These three subgenres appear as screen paintings (byōbu-e) and door or partition paintings (fusuma-e). Typically, a poet would compose a waka on a scene depicted in a screen painting, often from the point of view of a figure in the scene, or would compose a waka as a viewer of the screen. The waka was then written on a poetry sheet and pasted onto the screen painting.

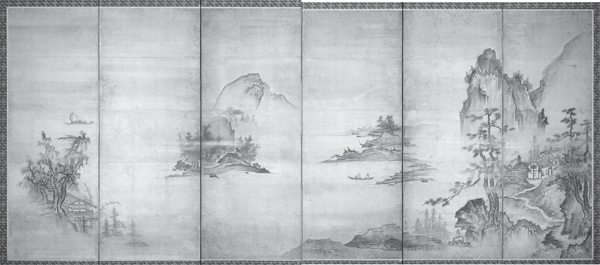

The Yoshinobu shū (Yoshinobu Collection, ca. 979), a private waka collection of the noted poet Ōnakatomi no Yoshinobu (921–991), records the scenes on one such twelve-month screen painting (tsukinami-byōbu-e), with twelve poems by Yoshinobu, one for each month:4

First Month | Pulling up pines on the Day of the Rat |

Second Month | Preparing a rice field |

Third Month | Regret at the scattering of the cherry blossoms |

Fourth Month | Visiting a mountain retreat with the cherry blossoms still in bloom |

Fifth Month | Thatching sweet flag on the fifth day of the Fifth Month, small cuckoo |

Sixth Month | Performing an exorcism (harae) |

Seventh Month | Celebrating the Star Festival (Tanabata) |

Eighth Month | Greeting Horses (Komamukae) |

Ninth Month | Harvesting rice at a provincial residence |

Tenth Month | Fishing weirs and bright foliage |

Eleventh Month | Celebrating a god festival (kami matsuru) |

Twelfth Month | Falling snow |

This kind of twelve-month screen painting became very popular in the mid-Heian period. In this particular painting, the seasonal topics include both agricultural activities and annual observances. The remaining topics are plants, birds, and atmospheric conditions commonly found in imperial waka anthologies. Since Heian aristocratic women rarely went out, screen and partition paintings, decorated with small sheets of waka, became, along with the garden, a surrogate for nature. The women often composed poems not on the actual small cuckoo that they heard in the garden, but on the hototogisu painted on a screen painting or partition.

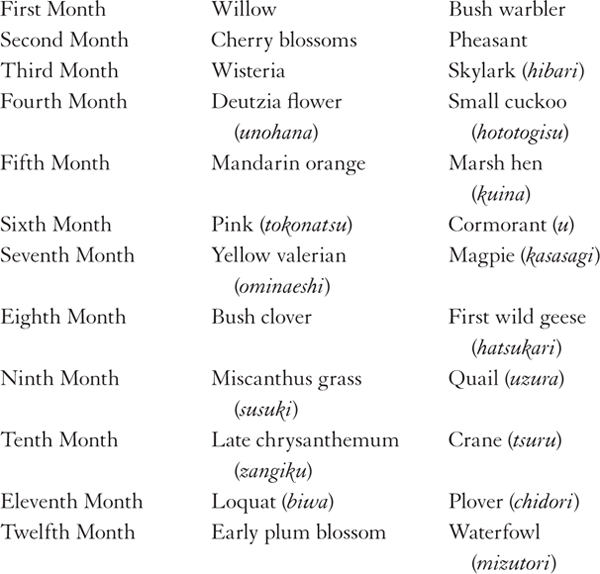

In the Kamakura period, a new form of seasonal painting emerged: the painting album (gachō), which was much smaller than the multiscene screen painting, usually with one scene per painting. One of the most popular subjects for this new format was Fujiwara no Teika’s (1162–1241) Jūnikagetsu kachō waka (Poems on Flowers and Birds of the Twelve Months, 1214), which presents one flower poem and one bird poem for each of the twelve months:5 Significantly, Teika’s Jūnikagetsu kachō waka reflects a level of seasonal specificity and imagistic association (matching classical birds with classical plants) even more pronounced than that in Heian screen paintings. From the late Heian period, poems on each month of the year (tsuki-nami waka) had been composed at monthly gatherings (utakai) at the Office of Poetry (Waka-dokoro) and at the residences of prominent waka poets. By the Northern and Southern Courts period (1336–1392), this custom had spread to various other classes. As part of this trend, Teika’s Jūnikagetsu kachō waka became a very popular subject for painting that was frequently taken up by Tosa and Kanō school painters as well as by Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743), a ceramics artist of the Rinpa school who created twelve square dishes decorated with these poems and their illustrations.6 The result was that Teika’s twelve-month bird-and-flower poems and paintings based on them appeared not only on screens and partitions and in painting albums, but also on ceramics and clothing.

FLOWERS AND BIRDS OF THE TWELVE MONTHS

Fujiwara no Teika’s Poems on Flowers and Birds of the Twelve Months (Jūnikagetsu kachō zu, 1214), a poetic matching of birds and flowers to specific months, was widely illustrated, as in this example from Snipe Preening Its Feathers (Shigi no hanegaki, 1691, 1781): (right) First Month, with willow and bush warbler, and (left) Second Month, with cherry blossoms and pheasant. (Courtesy of the author)

Teika’s Jūnikagetsu kachō waka remained a popular painting topic through the Edo period. A good example is the series of woodblock prints from shigi no hanegaki (Snipe Preening Its Feathers, 1691, 1781), a waka handbook and anthology that contains two poems (one on a bird and the other on a flower) per page (figure 8). The willow poem for the First Month reads: “Is it the color of the wind that comes with spring—the threads of the green willow are dyed greener with each passing day” (Uchinabiki haru kuru kaze no iro nare ya hi wo hete somuru aoyagi no ito). The poem at the top and the picture at the bottom of the page evoke the classical associations of early spring: the new green of spring, the green willow (aoyagi), and its thin new branches bending in the wind.

In the Edo period, the elegant world of birds and flowers spread to urban commoners’ cultural sites, particularly the pleasure quarters and kabuki (what were called the akushō [bad places] in the major cities), and became part of a world of “drink and sensuality,” to use the words of Asai Ryōi in the preface to his Ukiyo monogatari (Tale of the Floating World, 1666). Indicative of the spread of the kachō fūgetsu (flower and bird, wind and moon) tradition was the popularity of flower cards (hanafuda or hana-garuta), a card game that appeared in the seventeenth century. Flower cards centered on twelve flowers, trees, and grasses representing the twelve months: pine (First Month), plum blossoms (Second Month), cherry blossoms (Third Month), wisteria (Fourth Month), iris (Fifth Month), peony (Sixth Month), bush clover (Seventh Month), miscanthus grass with moon (Eighth Month), chrysanthemum (Ninth Month), bright autumn leaves (Tenth Month), willow (Eleventh Month), and paulownia (Twelfth Month). There were four cards for each plant (each with a different number of points), creating a total of forty-eight cards.7 With the exception of the peony, which entered the poetic canon in the Edo period, all the images are from classical poetry of the Heian period and reflect urban commoners’ knowledge of the poetic and cultural associations of the months.8

Poetic Places

Poetic places associated with classical poetry (utamakura) were the spatial or topographic equivalent of seasonal topics (kidai).9 As Fujiwara no Tameaki suggests in Chikuenshō (Collection from a Bamboo Garden, 1285), in classical poetry the circle of poetic associations, which was called the poetic essence (hon’i), took precedence over the actual appearance of the place:

In composing poetry on Naniwa Bay, one should write about the reeds even if one cannot see them. For Akashi and Sarashina, one should compose so that the moon shines brightly even if it is a cloudy evening. As for Yoshino and Shiga, one composes as if the cherry trees are in bloom even after they have scattered.10

Shōtetsu (d. 1459), a waka poet of the Muromachi period, writes in Shōtetsu monogatari (Conversations with Shōtetsu, 1448):

If someone were to ask me what province Mount Yoshino is in, I would answer that for cherry blossoms I think of Mount Yoshino, for bright autumn leaves, I think of Mount Tatsuta, and that I simply write my poems accordingly, not caring whether these places are in Iga or Hyūga Province. It is of no practical value to remember which provinces these places are in. Though I do not attempt to memorize such things, I have come to know that Yoshino is in Yamato Province.11

As these remarks reveal, the waka poet should not be concerned with the actual physical appearance or location of the utamakura, but with its poetic essence. Thus the Bay of Naniwa was associated with reeds; Akashi and Sarashina, with the autumn moon; Yoshino and Shiga, with cherry blossoms; Tatsuta Mountain, with colorful autumn leaves; and the Ōyodo River and Sumiyoshi, with pines. Indeed, for classical Heian poets, who rarely, if ever, left their homes in the capital, utamakura were often a means of enjoying the pleasures of travel without traveling.

The connection between a famous place and the seasonal motifs from waka became so close that a single motif in a painting could evoke a specific place and its seasonal associations. For example, the place-name Yoshino immediately elicited cherry blossoms and snow; Kasuga, an utamakura in Yam-ato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture), brought to mind young herbs (wakana) and deer; bright foliage on a river recalled the Tatsuta River; yellow kerria (yamabuki) on water referred to the Tama River in Ide; autumn grasses (particularly miscanthus grass [susuki]), a moon, and a wild field signaled Musashino Field, an utamakura in the Kantō region; and a bridge and willows stood for the bridge at Uji.12

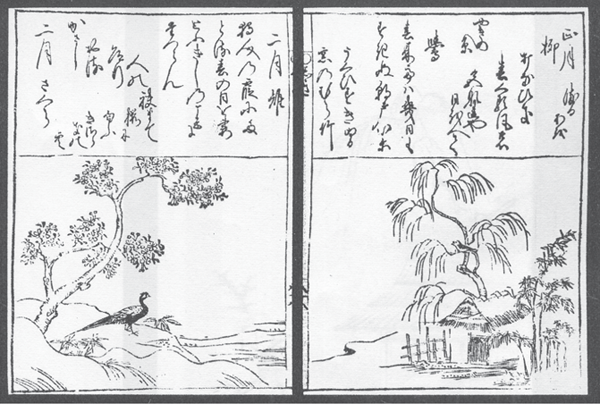

A good example of this phenomenon is the painting Blossoming Cherry Trees in Yoshino (sixteenth century), which depicts the blossoms of cherry trees scattering deep in the mountains at Yoshino (figure 9). Yoshino, referring to both the mountain and the river that flows at its base, was an utamakura in Yamato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture). As a result of numerous poems in the Kokinshū and subsequent waka anthologies, Yo-shino became closely associated with cherry blossoms and snow; and in the late Heian period, it also became linked with reclusion. The simple combination of a mountain, a river, and cherry blossoms signaled to the viewer of this screen that the scene was of Mount Yoshino and the Yoshino River, calling to mind a plethora of classical poems on the topic.

In similar fashion, bright foliage on a river meant the Tatsuta River in the autumn. Indeed, by the Edo period, the combination of cherry blossoms at Yoshino and bright foliage at Tatsuta—representing spring and autumn, respectively—became a popular painting topic called clouds-brocade (unkin), based on a pair of visual transpositions (mitate): cherry blossoms mistaken for clouds, and bright foliage taken for brocade. The Yoshino–Tatsuta Screen Painting (Nezu Museum, Tokyo) consists of a pair of screens, one filled with cherry blossoms and the other with bright foliage: this combination alone meant Mount Yoshino / Yoshino River and Tatsuta River.13 A colorful Nabeshima ware dish, with green and red maple leaves over blue waves on a white background, is an example of how the Tatsuta River became a ubiquitous design motif in ceramics (figure 10). No label or text indicates that this is Tatsuta, but the combination of colored leaves and waves leaves no doubt about its autumn identity.

Waka Naming

Since a single word or phrase from a classical poem had the power to evoke a specific poem, a cluster of poems, or a particular poetic topic, waka names (uta-mei) were used in a broad range of arts, from bonseki (sand-and-stone landscape on a tray) to chanoyu (tea ceremony). They even extended to sumo wrestlers, who were often given utamakura names such as Kasuga-yama (Mount Kasuga), a mountain to the east of Kyoto.

A good example of this phenomenon is the bonseki, a miniature landscape constructed on a black lacquer tray with small stones and sand, which became popular in the Muromachi period and was often used in chanoyu and ikebana (flower arrangement). Bonseki, which were called matchbox gardens (hako-niwa) in the Edo period, were given names such as Yume no ukihashi (Floating Bridge of Dreams), drawn from a famous poem by Fujiwara no Teika, or Zan-setsu (Lingering Snow), suggesting a physical resemblance to a waka-esque image of nature. They were also named after utamakura such as Kurokami-yama (Black-Haired Mountain) and Mount Fuji. The result was a kind of double visual transposition in which the bonseki represented a particular landscape in miniature while evoking associations through a waka name or word.14

The associative power of waka is also evident in the practice of naming (nazuke) tea utensils. The tea ceremony pioneer Kobori Enshū (1579–1647), who had studied the classical poetry of Teika, was influential in popularizing the practice of naming tea bowls and other tea utensils, such as the tea scoop (chashaku) named Matsu no midori (Shōroku; Green of the Pine) by the well-known waka poet Kinoshita Chōshōshi (1569–1649) (figure 11). The name derives from a poem in the Kokinshū: “The everlasting green of the pine, when spring arrives, becomes a still more superior color” (Tokiwa naru matsu no midori mo haru kureba ima hitoshio no iro masarikeri [Spring 1, no. 24]). The waka observes that the green of the pine, an evergreen and a symbol of the unchanging, becomes even more intense with the arrival of early spring. The name thus transforms a piece of undecorated bamboo (used for scooping tea powder) into a cultural object that recalls this or similar waka. Typically, in the course of a tea ceremony, the tea master would select these named tea utensils in conjunction with the hanging scroll in the alcove, the decorated ceramics, and the occasion itself to weave a “narrative” of the seasonal moment.15 Chanoyu, which centered on the preparation and presentation of tea, also involved the presentation, “naming,” and consumption of sweets (wagashi) such as Kōbai (Crimson Plum Blossoms) and Ochiba (Scattered Tree Leaves), which also embodied the seasonal moment.

BLOSSOMING CHERRY TREES IN YOSHINO

In this sixteenth-century screen painting, a mountain stream runs through a valley dense with cherry blossoms, a hallmark of Mount Yoshino. There is a graceful stand of golden-yellow kerria (yamabuki) on an islet in midstream. The rippling water is outlined in silver, now oxidized, and the blossoms are modeled with powdered white shell. (Six-panel folding screen, ink, color, silver, and gold leaf on paper, 147.3 x 351.4 cm [58 x 138.3 inches], John C. Weber Collection, Photo: John Bigelow Taylor)

NABESHIMA WARE DISH WITH TATSUTA RIVER

On this Nabeshima ware dish (late seventeenth or early eighteenth century), the bright design—blue waves and crimson, yellow, and green leaves—alludes to the Tatsuta River, on which so many autumn poems were written and which became synonymous with autumn. (Ceramic, 7.8 x 4.2 x 2.2 inches. Courtesy of the Suntory Museum of Art, Tokyo)

TEA SCOOP WITH CASE

The poet Kinoshita Chōshōshi named this tea scoop Green of the Pine (Matsu no midori or Shōroku). This practice of “naming (tea utensils and tea houses) after classical poems” (uta-mei) exemplifies the manner in which the poetic tradition was utilized in the tea ceremony, which came to the fore in the Muromachi and early Edo periods. (Courtesy of the Suntory Museum of Art, Tokyo).

Renga and the Seasons

In the Muromachi period, waka was superseded in practice by renga, which became the most popular late medieval poetic form, flourishing from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century. The seventeen-syllable opening verse of a renga sequence, known as the hokku (which eventually became an independent genre called haiku), required a seasonal word, and each subsequent verse (tsukeku) in the sequence (usually of thirty-six, fifty, or a hundred verses) had to be identified as either seasonal or non-seasonal. In order to ensure the necessary change or movement in the linked-verse sequence, rules were established to make certain that the sequence passed through the four seasons in a regulated fashion. In Muromachi-period renga manuals, each season is divided into three phases—early, middle, and late—or into months. In waka, for example, hail (arare) is a winter topic, but in Satomura Jōha’s (1525–1602) Renga shihōshō (Shihōshō: Collection of Treasures, 1586) and in such early Edo haikai handbooks as Matsue Shigeyori’s (1602–1680) [Hanahigusa (Sneeze Grass, 1636) and Kitamura Kigin’s (1624–1705) Zōyamanoi (Additional Mountain Well, 1667), arare is listed specifically under mid-winter, or the Eleventh Month. That is to say, renga was even more precise about seasonal associations than waka (including Teika’s Jūnikagetsu kachō waka) had been.

A distinction was also made between seasonal topics (kidai), which had an established cluster of poetic associations, and seasonal words (kigo), which were simply words identified as belonging to a particular season. As renga handbooks suggest, the number of seasonal topics in renga ranged from 160 to 180, about the same number as existed in waka, but the number of seasonal words reached over 300. At the end of Hekirenshō (1345), one of the first renga manuals, Nijō Yoshimoto (1320–1388) gives a comprehensive list of 115 “topics for the twelve months.” The following is the repertoire for spring:16

FIRST MONTH: Beginning of spring [risshun], Day of the Rat [Nenohi], picking parsley [seri tsumu], new herbs, bush warbler, melting ice, melting snow, burned fields, cold wind, plum blossoms (through the Second Month)

SECOND MONTH: Kasuga Shrine Festival, willow, cherry blossoms, bracken [warabi], returning wild geese (from the fifteenth day of the Second Month to the beginning of the Third Month), pheasant, digging up the rice paddies [tagaesu], rice-seedling beds [nawashiro]

THIRD MONTH: Frog, spring horses, skylark, cuckoo [yobukpdori],17 iris [kakitsubata], yellow kerria [yamabuki], azalea, late cherry blossoms, wisteria, end of spring [boshun]18

This list closely resembles the topics in the Horikawa hyakushu (Horikawa Poems on One Hundred Fixed Topics, 1105), the collection of poems on a hundred fixed topics (hyakushu-uta) that was so influential in establishing seasonal topics for late Heian and early Kamakura waka. Renga poets worked with essentially the same set of topics while slowly adding a limited number of new ones. It was not until the appearance of Renga shihōshō which includes more than 300 seasonal topics, that the number increased significantly, with the addition of such topics as pear blossoms (nashi no hana).

In composing on a set topic (dai), as in a poetry contest (uta-awase) or the [hyakushu-uta, the waka poet was expected to know the established associations of the topic, referred to as the poetic essence (hon’i), and to work within those parameters. This “poetic essence” is emphasized in Renga shihōshō: “Renga follows what are called poetic essences [hon’i]. For example, even though a strong wind or a thunder shower may occur in spring, the wind and the rain must be quiet. That is the natural essence of spring.”19 Jōha stresses that the season itself has a poetic essence, which must not be violated. On the topic of summer night, the Renga shihōhō notes: “The poetic essence of the summer night is brevity. In a poem, when night arrives, it immediately becomes dawn.”20

Even if the poet feels that the summer night is long, it must be described as short. This requirement was based on poetic precedent going back to the Kokinshū, which had established a core of associations that were refined in subsequent imperial waka anthologies. In other words, the renga poet looked not to nature but to classical precedent to understand the “poetic essence” of the seasonal topic. This heavy reliance on established associations was not regarded as a restraint so much as a rich foundation and a bridge to the audience, who could travel into the literary past through the shared topic.

The Three Realms and Cosmological Order

Seasonal topics not only followed a highly calibrated sequence, but were informed by a complex cosmological order, commonly referred to as the Three Realms (Ten-chi-jin): Heaven, Earth, and Humanity. Three Realms cosmology is evident in the topical sequence of the miscellaneous poems in books 8 and 10 of the Man’yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, ca. 759). For example, under spring miscellaneous poems in book 10, the topics implicitly move from Heaven (atmospheric conditions) to Earth (birds and plants) to Humanity (joy of meeting). A similar kind of cosmological hierarchy appears in Chinese dictionaries and Chinese topical encyclopedias (Jp. ruisho, Ch. leishu) that were imported to Japan from the Nara period onward. For example, the Yiwen leiju (Jp. Geimon ruijū; Literary Encyclopedia, 624), an early Tang (618–907) encyclopedia with literary examples, is divided into forty-five (or forty-six) categories and fills a hundred volumes. It begins with celestial (Heaven) categories (astronomical phenomena [ten] and seasonal phenomena [saiji]; followed by terrestrial (Earth) subjects (land [chi], states [shū], prefectures [gun], mountains, and water); moves to human affairs (Humanity), which range from emperors to weapons; and ends with such topics as trees, land animals, sea creatures, insects, felicitous events, and disasters. This type of organization is also evident in topical poetry collections of the Heian period, such as the kokin rokujō (Six Books of Japanese Poetry Old and New, 976–987), Wakan rōeishū (Japanese and Chinese-Style Poems to Sing, ca. 1012), and Senzai kaku (Superior Verses of a Thousand Years, 947–957).21 For example, the Kokin rokujō a major topical waka collection from the mid-Heian period, consists of six volumes:

Book 1. Seasonal phenomena (saiji) and Heaven (ten)

Book 2. Mountains, rice fields, wild fields, the capital, houses, people, Buddhist matters Book 3. Water

Book 4. Love, celebration, parting

Book 5. Various thoughts, clothing, color, brocade

Book 6. Grass, insects, trees, birds

Heaven, Earth, and Humanity appear in sequence and are followed by plants, animals, and insects. The Jūdai hyakushu (One Hundred Poems on Ten Topics, 1191), a hundred-poem set (hyakushu) composed by four poets, including Fujiwara no Teika, has ten sections (topics) with ten poems each. The sections are arranged in a related but slightly different order from those in the Kokin rokujō beginning with Heaven, Earth, dwellings, grass, trees, birds, animals, and insects, and ending with Shinto matters and Buddhist matters—that is, with Humanity coming last.22

Sequencing in classical linked verse was based on the intersection of these two configurations: seasonal topics and cosmological order. As Mi-tsuta Kazunobu has shown, the elaborate rules of seriation in renga apply to two types of topics: major topics drawn from the imperial waka anthologies and topics drawn from the Three Realms. Renga masters developed very complex rules (shikimoku) for the distribution of topics in linked verse. For example, spring and autumn had to continue for a minimum of three verses and for a maximum of five verses, and there had to be nine verses before another verse could be composed on the same season. Distinctions were also made among major topics (maximum of five successive verses), medium topics (maximum of three successive verses), and minor topics (maximum of two successive verses).

Imperial waka anthology–type topics

Major (five successive verses): spring, autumn, love

Medium (three successive verses): summer, winter, complaints, Shinto matters, Buddhist matters, travel

Three-Realm cosmology-type topics

Medium (three successive verses): mountains, water, dwellings

Minor (two successive verses): luminous objects, times of day, human affairs, ascending objects, descending objects, famous places, animals, plants, clothing23

Astronomical phenomena (such as the sun, moon, and stars) appear here as “luminous objects” (hikari-mono), while atmospheric phenomena (tenshō) are divided into “ascending objects” (sobiki-mono) (such as autumn mist [kiri], clouds, spring mist [kasumi], and smoke) and “descending objects” (furi-mono) (such as rain, snow, frost, and dew). Topics from these categories had to be separated by at least three verses before they could appear again.24 All other cosmological categories had to be separated by five verses. These include plants (ue-mono) and animals (ugoki-mono) as well as the key triad of “mountain-related things” (sanrui), such as mountain peak, hill, and waterfall; “water-related things” (suihen), such as sea, bay, and waves; and “dwellings” (kyosho), such as village and hut. These elements were sometimes subdivided further by the criteria of stasis (tai) and movement (yū), in which, for example, the sea and bay were considered to be static, while waves, water, ice, and salt were considered to be mobile.25 More important, cherry blossoms (hana), representing spring; the moon, representing autumn; and love were required to appear at regular intervals in the linked-verse sequence.26 The result is that the major waka topics (centered on spring and autumn), followed by the medium waka topics (such as summer, winter, complaints [jukkai], Shinto matters, Buddhist matters, and travel), formed the essential building blocks of renga. At the same time, as is evident in the rules on celestial objects and atmospheric conditions, linked verse was designed to make the participants travel through the Three Realms, journeying through time and space.

The opening of Minase sangin hyakuin (One Hundred Verses by Three Poets at Minase), a famous Muromachi-period renga sequence composed by Sōgi (1421–1502), Shōhaku (1443–1527), and Sōchō (1448–1532) in 1488, on the twenty-second day of the Third Month, shows how these various elements were brought into play.27

1. While it is snowing, | |

| Sōgi | |

Yuki nagara yamamoto kasumu yuube kana |

[Spring]28 |

2. Flowing water in the distance, | |

| Shōhaku | |

| Yuku mizu tooku ume niou sato | [Spring]29 |

3. In the river breeze, | |

| Shōchō | |

Kawakaze ni hitomura yanagi haru miete |

[Spring]30 |

4. Dawn when one can clearly hear | |

| Sōgi | |

Fune sasu oto mo shiruki akegata |

[Miscellaneous]31 |

5. Is the moon | |

| Shōhaku | |

Tsuki ya nao kiri wataru yo ni nokoru ran |

[Autumn]32 |

6. Autumn comes to an end | |

| Sōchō | |

Shimo oku nohara aki wa kurekeri |

[Autumn]33 |

7. Oblivious to the heart | |

| Sōgi | |

Naku mushi no kokoro tomo naku kusa karete |

[Autumn]34 |

8. When I ask about the shrub fence, | |

| Shōhaku | |

| Kakine o toeba arawa naru michi | [Miscellaneous] |

In verse 1, snow falls, but spring mist rises at the foot of the mountain, indicating the transition from winter to spring. In verse 2, which is read together with verse 1, water is flowing in the distance, signaling that the mountain snow has melted. Verse 3, which continues the spring scene, adds movement: the willow leaves are blowing in the river breeze. Verse 4, which is miscellaneous, or non-seasonal, prepares the transition from spring to autumn and places a boat on the river: the sound of the oars can be heard in the quiet of the dawn. Verse 5, which is the required moon (autumn) verse, returns to atmospheric phenomena, but instead of a descending object (snow), it presents an ascending object (autumn mist). Verse 6 makes the moon of the previous verse into a lingering late-autumn moon of the Ninth Month. Verse 7 brings us to the end of autumn, with the crying of insects and withering grass. The eight-verse sequence moves from a nature-centered landscape (spring snow, plum blossoms) to a human-centered landscape (village with willows, boat on a river), to a nature-centered landscape (autumn moon, frost, insects), and back to a human-centered one (question about shrub fence). Temporally, a night sequence (verses 4 and 5) is sandwiched between two daytime sequences.35 Needless to say, without a knowledge of the classical seasonal associations, a participant could not follow the subtle seasonal or spatial movement that lies at the heart of such a sequence.

The opportunity to experience each of the four seasons as well as to move from one to the next was a major attraction of a renga session. In Tsu-kuba mondō (Questions and Answers at Tsukuba, 1372), a major treatise on renga, Nijō Yoshimoto, one of the founders of classical linked verse, observes: “When you think it is yesterday, today has passed, and when you think it is spring, it is autumn. When you think that the flowers have bloomed, things shift to the bright autumn leaves.”36 Responding to the question of whether renga can be an aid to enlightenment, Yoshimoto notes that to see nature in this fashion—the flowers coming into full bloom and the leaves withering and falling (hika-rakuyō)—is to realize the impermanence of this world.

As Mitsuta Kazunobu has argued, these various topics and categories, as they appear in Renga shinshiki (New Rules for Linked Verse, 1372), are in pairs and can be divided into two worlds, the natural world and the human world, which correspond in symmetrical fashion:

NATURAL WORLD

Luminous objects, time

Descending objects, ascending objects

Mountain things, water things

Plants, animals

HUMAN WORLD

Shinto, Buddhism

Love, personal grievances

Travel, famous places

Dwellings, clothing

Not only are major waka topics combined with elements of the Three Realms, but the human and natural worlds correspond in subtle ways. For example, in the human world, Shinto and Buddhism stand over human beings, just as light and time stand over the Earth in the natural world. Love and personal grievances connect humans to gods and buddhas, much as descending and ascending objects connect Heaven and Earth. People travel to famous places, which are marked by mountains and water. Dwellings and clothing represent the human world in the way that animals and plants stand for the natural world.37 As noted earlier, this cosmology was inherited from earlier topical waka anthologies and Chinese topical encyclopedias, with the main difference being that Renga shinshiki divides atmospheric phenomena into two categories: ascending objects and descending objects.

This topical categorization of the universe continued into the Edo period, in haikai (popular linked verse) handbooks, and remains in the modern period in the form of saijiki (seasonal almanacs) for modern haiku poets. The Haiku saijiki (Haiku Seasonal Almanac, 1959), one of the most popular seasonal haiku almanacs in the postwar period, lists seven categories for the four seasons plus New Year (shinnen)—seasonal phenomena (jikō, such as the Eighth Month or late autumn; astronomical and atmospheric phenomena (tenmon), such as the harvest moon; terrestrial phenomena, such as autumn mountains; human activity, such as Tanabata and fireworks; religious activity, such as Higan (Buddhist services during the vernal and autumnal equinoxes); animals; and plants—a structure that directly echoes that of the early Chinese encyclopedias, such as the Yiwen leiju.38 The Shinsaijiki (New Seasonal Almanac, 1951), a well-known saijiki edited by the haiku poet Taka-hama Kyoshi, has six categories—seasonal phenomena, astronomical and atmospheric phenomena, terrestrial phenomena, human activity, animals, and plants39—eliminating the ambiguous distinction between human activity and religious activity. A similar topical arrangement is found in the Nihon daisaijiki (Great Japanese Seasonal Almanac, 1982), edited by Mizuhara Shūōshi, Katō Shūson, and Yamamoto Kenkichi.40 In short, with some variation, the same fundamental categories continue to appear over a 1400-year span.

Contrasting Landscapes

Not only did Japanese poetry, particularly waka, have a profound effect on visual culture, but painting and other visual media had a huge impact on poetry and its representation of nature and the seasons. The landscape of medieval waka and renga, for example, was greatly influenced by Chinese ink-painting styles of the Song period (960–1279). Japanese landscape ink painters were drawn to the works of Mu Qi (Jp. Mokkei [d. ca. 1280–1294]) and other Chinese artists whose paintings of tall, distant, mist-covered mountains drew attention to the atmospheric and light conditions surrounding high mountains and bodies of water.

Kazamaki Keijirō has persuasively argued that the most prominent feature of the seasonal waka poems in the Gyokuyōshū (Collection of Jeweled Leaves, 1312), a noted imperial waka anthology edited by Fujiwara (Kyōgoku) Tamekane (1254–1332) in the late Kamakura period, is their focus on such atmospheric conditions as light breaking through the clouds, spring mist, spring evening after rain, and evening sunlight in autumn—with natural light often playing a major role.41 This trend reached a peak with the Fūgashū (Collection of Elegance, ca. 1346–1349), another important imperial waka anthology that continued the style of the Kyōgoku school into the Northern and Southern Courts period, as exemplified by such poems as this one by Fujiwara no Tamekane: “On the mountain edge, where the setting sun has just vanished, a peak beyond the mist-covered mountain has appeared!” (Shizumihatsuru irihi no kiwa ni arawarenu kasumeru yama no nao oku no mine [Spring, no. 27]).”42

A similar kind of landscape appears in renga of the Muromachi period, particularly that by Sōgi, as in verse 1 of Minase sangin hyakuin. Okuda Isao has noted the distant perspective on the mountains and water—for example, looking up at the mountain enshrouded in mist in verse 1 and taking a distant view of the flowing water (the confluence of the Yodo and Katsura rivers at Minase) in verse 2. A key verb is “to look from afar” (miwatasu), as found in a poem in the Shinkokinshū (New Anthology of Poetry Old and New, 1205) by Retired Emperor GoToba, alluded to in verse 1 of Minase: “When I look from afar, foothills of the mountain wrapped in spring mist, the river at Minase—why did I think evening was best in autumn?” (Miwataseba yamamoto kasumu Minasegawa yuube wa aki to nani omoikemu [Spring 1, no. 36]). The boatman or fisherman on the water, enveloped in spring mist, a familiar trope in ink painting, also appears in Minase, as it does elsewhere in the linked-verse sequence (nos. 51 and 52).43

Renga is a poetry of overtones: each verse leaves open an infinite number of possibilities for textual extension, thus stimulating the poetic imagina-tion. The enshrouded waters and distant mountains of Chinese and Japanese ink paintings similarly excite the viewer’s imagination by visual indirection. This kind of landscape is also prominently featured in “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang” (Shōshō hakkei) paintings, which became very popular in the Muromachi period, particularly among Japanese Zen priests. The “Eight Views” in their classical order are

Clearing Storm over a Mountain Village

Sunset over a Fishing Village

Sails Returning from Distant Shores

Night Rain on the Xiao and Xiang

Evening Bell of a Temple in Mist

Autumn Moon over Lake Dongting

Descending Geese at a Sandbar

Evening Snow on a River

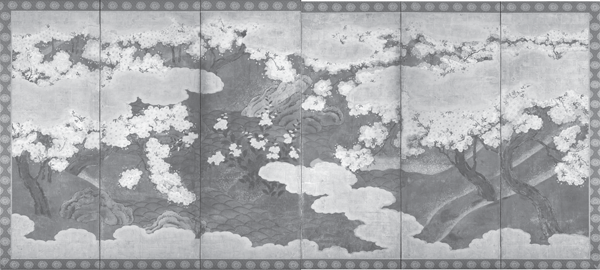

The “Eight Views” focus not only on mountains and open waters, but on atmospheric conditions and time of day, which also had interested Kamakura-period poets such as Fujiwara no Shunzei and Fujiwara no Teika. A good example of an “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang” painting done by a Japanese artist is a screen painting by the priest-painter Zōsan (figure 12). Scenes like these, with tall mountains and bodies of water enveloped in different atmospheric conditions, inspired many Zen Buddhist poets composing kanshi (Chinese-style poetry) to write on the topic of the Xiao and Xiang and on its Japanese equivalents, such as “Eight Views of Ōmi” (Ōmi hakkei), the scenery surrounding the coast of Lake Biwa.

Medieval renga poets also found the relationship among the scenes in “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang” paintings to be an apt metaphor for the linking of verses, in which the added verse combines with the previous one to create a new scene but also pushes off from the scene generated by the two previous verses to create both temporal and spatial movement.44 In other words, the different scenes in the “Eight Views” were regarded as both contiguous and semi-autonomous, the fundamental assumption behind linking verses in renga. Equally important were the movement from one season to the next and from one time of day or atmospheric condition to another. “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang” screen paintings, as they evolved in Muromachi Japan, moved from spring on the far right, through summer and autumn, and ended with winter on the far left, affiliating them with the four-season screen paintings, which originated in the Heian period.

EIGHT VIEWS OF THE XIAO AND XIANG

The right-hand screen of a pair of six-panel folding screens painted by Zōsan in the first half of the sixteenth century depicts the first four of the “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang”: (right to left) “Clearing Storm over a Mountain Village,” “Sunset over a Fishing Village,” “Sails Returning from Distant Shores,” and “Night Rain on the Xiao and Xiang.” This Chinese-derived topic, which became highly popular in Japan, exemplifies the kind of monochromatic landscape that came to the fore in the medieval period, particularly the high mountains and large bodies of water enveloped in different kinds of atmospheric conditions, each of which indicates a specific season. The scenes begin with spring on the far right of the right-hand screen and end with winter on the far left of the left-hand screen. (Light color, ink, and gold on paper; 62.2 x 143.8 inches. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Fenollosa-Weld Collection, 1911, no. 11.4150)

Classical poetry and its successor, classical linked verse, had a profound influence on the visual arts from the Heian to the Muromachi period, from screen paintings to tea ceremony, with multiple genres (such as painting and waka) often working together in an interactive fashion. By the late medieval period, the phases of the seasons and other aspects of nature became increasingly codified to the point where renga masters were necessary to guide the practitioners in both the associations and the complex rules. As the notion of topical poetic essences (hon’i) and the elaborate cosmology developed by renga poets suggest, medieval poetry was not aimed at consistently realistic representation of nature so much as at re-presentation of both distant worlds (such as an imagined China or Heian court) and contemporary scenes (such as farmers in the rice field, warriors in battle, priests in the provinces). In renga, the participants freely traveled from one world to another, from country to city, and from one historical period to another. Renga became extremely popular among educated samurai and warlords during an era of constant warfare, particularly in the Warring States period (1478–1582). In the years after the Ōnin War (1467–1477), which destroyed the capital and its physical representations of the classical past, poetry offered a way to recapture a lost history. For educated warlords, disenfranchised nobles, and traveling poet-priests, the world of renga also served as a temporary escape from the bloodshed and harsh realities outside. In this sense, it had some similarities with the tea ceremony, which developed under Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) and others in the Muromachi period: the tea room provided a respite from the distractions of the city and the everyday world.

The same was frequently true of the ink paintings that depict recluses in the mountains, which hung in the alcove of the parlor-style (shoin-zukuri) residence, or the rock-and-sand garden (kare-sansui) first developed by Zen priests; these cultural forms often served as a world away from the world. Landscape, especially monochromatic landscape, as epitomized by Fujiwara no Teika’s famous poem on an autumn evening—” When I look from afar, there are neither flowers nor bright leaves: evening in autumn at a thatched hut by the bay” (Miwataseba hana mo momiji mo nakarikeri ura no tomaya no aki no yuugure [Shinkokinshū Autumn 1, no. 363])—attempted to look beyond the phenomenal world, often to enter into a transcendental or meditative state that could be embodied in the light of the winter or autumn moon or the shade of the pines in the mountains.

The tension between the mountain as the landscape of bright colors and the mountain as the topos of retreat appeared as early as the Kaifūsō (Nostalgic Recollections of Literature, 751), the first major anthology of kanshi, in the Nara period and extended through the Heian period in both poetry and prose. The opposition is articulated most famously by the waka poet-priest Saigyō (1118–1190), who writes of Mount Yoshino both as physically beautiful (with its cherry blossoms and snow) and as a representation of spiritual retreat from phenomenal and human bonds. The dynamic contrast was further deepened by the spread of Song ink painting and Zen-based views of the world, which resulted, by the Muromachi period, in two fundamental types of landscapes: the Heian landscape of cherry blossoms, bright foliage, and snow, and the medieval landscape of distant mountains and open expanses of water, typically represented by the rock-and-sand garden. Both of them came to manifest themselves in architecture, gardens, and flower arrangement and other arts of the alcove.