Interiorization, Flowers, and Social Ritual

It is not only classical Japanese poetry and its affiliated forms that created a sense of harmony with nature. Japanese architecture, beginning with the design of the palace-style (shinden-zukuri) residence of the Heian period (794–1185), also created a sense of intimacy with nature, which was carefully reproduced in the gardens of the house and which became the topic of much poetry. The shinden structure, in which the interior rooms opened directly onto the garden, created what we might call a veranda or “beneath the eaves” (nokishita) culture, occupying a space between the interior and the exterior that became the site of much of Heian court culture. In the medieval period (1185–1599), in the parlor-style (shoin-zukuri) residence, the same kind of interior-exterior continuity was maintained, but with the garden enclosed and greatly reduced in size. Even more important, the shoin residence featured a parlor with an alcove (tokonoma), a recessed space with a raised floor for the display of a hanging scroll and various offerings, which became the stage for a wide range of arts—tea ceremony, painting, renga (classical linked verse), waka (classical poetry), kanshi (Chinese-style poetry), calligraphy, incense, bonseki (sand-and-stone landscape on a tray), and flower arrangement. The alcove, the main display space for flower arrangement, literally brought nature into the residence and juxtaposed it with paintings and other visual arts. What, then, was the role of the garden, the tokpnoma, and flower arrangement in the construction of a secondary nature?

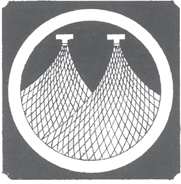

HEIAN-PERIOD PALACE-STYLE RESIDENCE

The palace-style (shinden-zukuri) residence of the Heian period typically had a central hall (shinden) to the north; two flanking buildings and two open corridors that extended south on both sides and were anchored by pavilions on the water; a large garden in the middle; and a lake, in which was a small island, to the south. The extensive use of verandas, open corridors, and open-pillar construction allowed most of the interior spaces to open directly onto the garden and the connecting passages to traverse the garden, thereby integrating the interior with the exterior and making the lake and island a central visual feature. (From Kazuo Nishi and Kazuo Hozumi, What Is Japanese Architecture? A Survey of Traditional Japanese Architecture, trans. H. Mack Horton [Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1985], 65–65. Courtesy of Kodansha International)

The Interior-Exterior Continuum

The palace-style residence of the Heian period created a direct sense of continuity between the interior and the garden, which was laid out to the south of the residence and was centered on a lake with an island (nakajima) (figure 13). The east and west corridors, which flanked the central hall (shinden), ran from the north (back of the house) to the south, directly to the lake, allowing the inhabitants to sit just above the water.

Kawamoto Shigeo, a noted architectural historian, has argued for two paradigmatic types of Japanese architecture: the walled-space type, in which the space is enclosed by a wall, door, or window; and the pillar-space type found in palace-style architecture, which creates direct spatial continuity between the interior of the building and the exterior court or garden.1 The walled-space type was imported from China in the Nara period (710–784) and was widely used in Buddhist temple and hall architecture. By contrast, the pillar-space type,2 which is of indigenous origin and was originally developed as a space for rituals, was the fundamental structure of the shinden-zukuri residence of the Heian period.

This “open” architecture, with its exterior–interior continuum, is evident in scenes on picture scrolls, such as the Kitano tenjin engi (Kitano Tenjin God Scroll, early thirteenth century), which shows the garden between the central hall and the east corridor, with the garden stream (yarimizu; a convention of the shinden-style garden) emerging from underneath the connecting hallway and flowing south. The garden and the living quarters are closely integrated so that the inhabitants pass over and through the garden by way of the covered but open hallways. In this kind of residence, the garden stream represents, in miniature, a meadow or valley with a river winding between rolling hills, thus bringing a rural landscape into the garden.

Architectural space usually is divided into the inside and the outside, with the peripheral wall as the barrier, but as the architectural critic Itō Teiji has argued, the palace-style residence and its parlor-style successor, which became the model for the traditional Japanese house, had one prominent feature that elides this division, what he calls the nokishita (beneath the eaves). The eaves, which extended over the sides of the building and the covered hallways, were originally designed in response to the monsoon climate, to protect the interior and the wall from the heavy and continual rain. In the summer, they also served to shield the interior from intense sunlight. The veranda, which was constructed directly under the eaves and was a major feature of both the shinden-style and the shoin-style residence, was regarded as an extension of the interior when used as a hallway or porch, but was considered part of the exterior when used as an adjunct to the garden. In other words, the Heian-period palace-style residence was constructed in such a way as to make living quarters and nature appear to share a continuous space.

This continuity between the interior and the exterior was enhanced by an assortment of movable interior structures—such as the sliding screen or partition (shōji), the hanging bamboo screen (misu), and the latticed shutter (shitomi)—all of which were designed to redefine the space in a room and allow air to circulate.3 For example, the parallel-door track system (hikichi-gai) allowed the partitions, both in the interior and on the periphery of the building, to slide behind one another, thus opening up the walls and interior of the house so that it was visually and spatially continuous with the exterior garden. “Nature” was also brought indoors in the form of screen paintings (byōbu-e) and door or partition paintings (fusuma-e). In The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari, early eleventh century) and other Heian court tales (as well as in Heian picture scrolls [emaki-mono; see figure 1]), the garden is a direct reflection of the interior state of a given character. Poems composed on, for example, the bush warbler or plum blossom in the garden often represent the thoughts or emotions of the literary character or painted figure. Fujitsubo (Wisteria Court), Yūgao (white-flowered gourd or moon-flower; literally, “Evening Faces”), and other female characters in Genji are named after their gardens or the plants that adorn their residences, and these gardens or plants came to symbolize the characters. This double (nature / human) structure is most dramatically demonstrated in the Genji monogatari emaki (The Tale of Genji Scrolls, ca. twelfth century) with the blown-roof (fukinuki-yatai) convention (see figure 1), which allows the viewer to see both the inside and the outside of the residence at the same time.

The cultural and poetic function of the garden is evident from the fact that Heian aristocrats filled their palace gardens with flowers, trees, and insects familiar from waka. In autumn, for example, they had gardeners plant miscanthus grass (susuki), yellow valerian or maiden flower (ominaeshi), pink (nadeshiko), and bush clover (hagi)—the most popular topics in autumn poetry. As revealed in the poetry contest (uta-awase) sponsored by Princess Kishi and held in a garden on the twenty-eighth day of the Eighth Month in 972,4 they also captured insects such as the bell cricket (suzumushi) and pine cricket (matsumushi) and released them into their urban gardens. The Kokon chomonjū (Collection of Things Heard and Written from Past and Present, 1254), an encyclopedic collection of anecdotes about court culture edited by Tachibana Narisue in the Kamakura period (1185–1333), describes Princess Kishi’s garden:

On the twenty-eighth of the Eighth Month of Tenroku 3 [972], Princess Kishi had miscanthus grass, orchid, aster, fragrant grass [kusa no kō], maiden flower, bush clover, and other plants planted in her garden at Nonomiya, the Shrine in the Fields, and then had pine crickets and bell crickets released into her garden. When she asked for immediate poetic compositions on these objects, each person wanted to be the first do so. In the garden, they created a hedge in a mountain village where a stag could approach; in another place, they created a spot where cranes could land on a rocky beach. Here grass was planted, and even insects were made to cry.5

Princess Kishi’s garden contained not only plants and insects, but also wild fields or a moor (no), a mountain village, and a seashore—all of which were represented in miniature on a portable island stand (shima-dai), also referred to as a cove beach stand (suhama-dai). The suhama-dai, an elaborately decorated landscape display used for poetry contests, was a small-scale reproduction of an island in the sea, featuring a sandy shoreline or cove beach. It could also be used to represent, as it did in Kishi’s garden, a mountain village and wild field, which were also components of “nature” in waka. During the poetry contest, the stand was placed inside the central hall and decorated with small replicas of creatures such as the bush warbler and crane, the topics on which the poetry contest participants had composed. At the end, the poem strips were pinned onto the appropriate part of the suhama-dai, literally fusing the poem with the landscape.6

A different kind of spatial continuity between the natural and human worlds is apparent in drama of the Muromachi period (1392–1573). In the noh theater, which became popular at that time, the stage is bare with almost no props; only the image of a pine decorates the back of the stage. The waki (side character) enters from stage left over the bridge and symbolically travels through the countryside in the so-called michiyuki (traveling song) section. The setting and season are established by the narration, the waki, the shite (protagonist), their attendants, and the chorus members, who sit stage right and often narrate in the third person. The minimal sets maximize the role of the narration, particularly waka-laced narration, which constructs a natural world in the mind of the audience. These noh plays are almost always set in a specific season, with a dominant seasonal motif that is directly related to the main topic, and are performed in that season. In the Kanze school, for example, Oimatsu (Old Pine) is performed in the First Month (early spring, New Year); Ume (Plum Tree) and Kochō (Butterflies), in the Second Month (mid-spring); Saigyō-zakura (Saigyō and the Cherry Blossoms), in the Third Month (late spring); Kakitsubata (Iris) and Fuji (Wisteria), in the Fourth Month (early summer); Bashō (Plantain Tree) and Omi-naeshi (Maiden Flower), in the Eight Month (mid-autumn); Momiji-gari (Bright-Foliage Viewing) and Kiku jidō (Chrysanthemum Child), in the Ninth Month (late autumn); and so forth.7

Unlike the bare stage of noh theater, the kabuki stage of the Edo period (1600–1867) had props and stage sets, but the architectural structure on the stage (usually a residence) reveals both the exterior and the interior (oku) at the same time, making the audience aware of the season even when the main action is indoors. The external space is further reinforced by the hanamichi (literally, “flower path”), a walkway that extends into the audience area and allows the actors to approach the main stage through the audience from the front of the theater, literally passing from outside to inside or vice versa. The action even within a strictly urban setting thus moves back and forth from the interior to the exterior, with the seasons being highlighted.

Kanadehon chū shingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, 1748 [puppet-play version]), probably the most popular of the kabuki plays, consists of eleven acts: the first through fourth acts are set in spring; the fifth and sixth acts, in summer; the seventh act, in autumn; and the eighth through eleventh acts, in winter—when the climactic revenge is finally carried out. On rare occasions, the entire play is performed in one day, but Edo-period kabuki troupes, like those of today, usually performed those acts that correspond to the actual season. For example, the first act of Benten musume meo no shiranami (Benten Kozo and the Five Thieves), first performed in 1862, is staged in the early spring (First Month), since the noted second scene (on the bank of the Iwase River) takes place under the cherry trees in full bloom. The kabuki dances (shosagoto) that provide important musical interludes are also linked to specific seasons. For example, Kagami jishi (Mirror Lion) and Fuji-musume (Wisteria Daughter) are spring dances, while Kiku jidō (Chrysanthemum Child) and Momiji-gari (Bright-Foliage Viewing) are autumn dances.8 To watch either noh or kabuki over the course of a year is to experience the unfolding of the four seasons to the accompaniment of song and dance.

The Alcove and Flower Arrangement

By the early Muromachi period, the large-scale aristocratic palace-style (shin-den-zukuri) architecture had been replaced by the much smaller parlor-style (shoin-zukuri) architecture, widely used in temple living quarters, guest halls, and mansions of the military elite. The parlor-style residence, the prototype of the traditional-style Japanese house, was named after the reading room or parlor (shoin), which faced the garden and served as a reception room. The parlor centered on an alcove (tokonoma), which became the symbolic focus for a wide range of cultural practices from renga to ikebana (flower arrangement).

The early Muromachi period witnessed a huge influx of paintings and decorative arts from Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) China, bringing a new array of landscape paintings (featuring dragons, tigers, herons, and mandarin ducks) and portraits of Shakyamuni Buddha; the bodhisattvas Kannon, Fugen, and Monju; the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove; and others. Heian-period painting formats, such as the emaki-mono and fusuma-e) required little or no space, and the byōbu-e could be moved around the room. But the Song and Yuan paintings, which were hanging scrolls (kake-jiku), had to be hung on a wall. This led to the development of the alcove, a recessed space for the display of hanging scrolls, incense burners, ceramics, and flower arrangements.

The architectural precursor to the tokonoma was the oshiita (raised area of the parlor), which was decorated with an image of the Buddha on the wall and three offerings to the Buddha—incense, flowers, and candles—in front of the image. An incense burner was placed in the center of the alcove, in front of the hanging scroll, with a flower vase to the left and a crane-and-turtle lamp, holding a candle that was lit as an offering, to the right. Later, with the development of the full tokonoma, the portrait of the Buddha was replaced by secular landscapes, bird-and-flower paintings (kachōga), or calligraphic texts, and the flower-incense-candle triad often was reduced to a single flower arrangement. Unlike the typical modern European painting, which usually remains on the wall all year around, the hanging scroll was frequently rotated, with a new scroll hung for each new occasion. The current season was thus reflected in the innermost part of the residence.

Another major architectural feature of the shoin-style residence was the enclosed garden, which was small in comparison with the vast garden grounds of the shinden-style residence. The back of the garden was walled off, so the garden resembled a landscape painting when viewed from the parlor, particularly if viewed through a window or an open sliding door. Unlike the large shinden garden, the shoin garden was to be looked at, not walked in. This was particularly true of the rock-and-sand garden (kare-sansui), which was often small, with the sand representing water, rivers, and sea, and the rocks evoking mountains and waterfalls. The kare-sansui, like many other related forms such as flower arrangement, depends on the technique of mitate, in which an image or a shape is used to suggest a larger and distant image. The mitate, which means something like “to see X as Y,” does not refer to the replication of a distant object or landscape so much as its evocation through one or more physical features, such as a figuration of rocks and sand. The kare-sansui could thus suggest a specific or general distant landscape while appearing natural in its configuration. Many rock-and-sand gardens include few or no flowers. Instead, the flowers moved indoors to the alcove in the form of the standing-flower arrangement, which, together with the enclosed scenic garden and the hanging scrolls, became a symbolic, interior representation of nature.

The earliest formal use of flowers in this manner in Japan was as an offering (kuge), either to the Buddha or to the spirit of the dead. By the twelfth century, Buddhism had spread to the point where Buddhist rites were carried out in private residences, and flowers were used as offerings in the home, placed before a Buddhist painting that substituted for the statue found in a Buddhist temple. This practice eventually resulted in the formal arrangement of flowers (ikebana), which evolved into two major types: rikka ( ; literally, “standing flower”), also called tatebana, a formal style that was established in the mid-fifteenth century and can be traced back to flower offerings placed before an image of the Buddha; and nageire (

; literally, “standing flower”), also called tatebana, a formal style that was established in the mid-fifteenth century and can be traced back to flower offerings placed before an image of the Buddha; and nageire ( , thrown-in flowers), a more casual style that was established in the seventeenth century and can be traced back to the Heian period, when aristocrats attached flowers to letters, placed flowers in vases, and held flower contests, at which flowers presented by the participants were compared and judged. Thus ikebana has both religious and secular origins, evident in attendant socioreligious practices: offerings or implicit prayers, seasonal greetings, elegant social communication, and aesthetic appreciation.

, thrown-in flowers), a more casual style that was established in the seventeenth century and can be traced back to the Heian period, when aristocrats attached flowers to letters, placed flowers in vases, and held flower contests, at which flowers presented by the participants were compared and judged. Thus ikebana has both religious and secular origins, evident in attendant socioreligious practices: offerings or implicit prayers, seasonal greetings, elegant social communication, and aesthetic appreciation.

Linked verse was also composed in front of the decorated alcove, which both indicated the season or occasion and served as an altar to Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (d. ca. 707), who had been designated one of the Thirty-six Poetic Immortals and had become the god of poetry. The Sendenshō (Transmission of the Immortal, written in the Muromachi period and printed in 1643), the oldest and most highly valued of secret treatises on rikka, notes that once the opening verse (hokku) of a linked-verse sequence has been composed, a flower arrangement should be made in accordance with the season of the hokku.9 That is to say, the flower arrangement marks the seasonal moment, just as the seasonal word (kigo) does in the hokku. The hokku, much like the flower arrangement itself, was generally considered to be a greeting to the host or the main guest of the gathering.

Due primarily to the accomplishments of Ikenobō Senkō (1536?–1621) and Ikenobō Senkō II (1575–1658), two key pioneers of rikka, the fundamental rules for standing-flower arrangement were established by the Kan’ei era (1624–1645). The central element was the center (shin) branch, the main axis, usually a tree branch that reached straight upward, to which was added the augmentation (soe), made up of branches, grasses, or flowers. At the bottom was the base (tai), which anchored the flower arrangement to the vase. This tripartite structure gradually expanded into “seven tools” (nanatsu no dōgu), or branch positions, and then into “nine tools” (kokonotsu no dōgu) or branch positions, which became the basic elements of the art of flower arrangement. Generally speaking, the tree branches (Ky-mono) were thought to give a sense of strength; the grasses (kusa-mono), by contrast, appeared gentle; and the “two-way things” (tsūyō-mono)—such as wisteria, peony, bamboo, yellow kerria, and hydrangea—which could be treated as either trees or grasses, connected the worlds of tree and grass.

The Ikenobō Sen’ō kuden (Ikenobō Sen’ō’s Secret Transmission) 1542), the first treatise to explain rikka systematically, provides a list of plants that can function as the shin for each of the twelve months:

SPRING

| First Month | Pine, plum tree |

| Second Month | Willow, camellia (tsubaki) |

| Third Month | Peach tree, iris (kakitsubata) |

SUMMER

| Fourth Month | Deuztia flower (unohana), Chinese peony (shakuyaku) |

| Fifth Month | Bamboo, sweet flag (shōbu) |

| Sixth Month | Lily, lotus |

AUTUMN

| Seventh Month | Bellflower (kikyō), lychnis (senō; literally, “immortal elder”) |

| Eighth Month | Hinoki (Japanese) cypress, white hinoki |

| Ninth Month | Chrysanthemum, cockscomb (keitō) |

WINTER

| Tenth Month | Chinese dogwood (kara-mizuki), nandina or heavenly bamboo (nanten) |

| Eleventh Month | Narcissus (suisen), Chinese aster (kangiku) |

| Twelfth Month | Loquat (biwa), early plum10 |

The shin is frequently taken from strong plants, such as pine, bamboo, plum, weeping willow, hinoki cypress, and Chinese juniper (ibukI). The three most valued trees (sanboku [the three trees]) in rikka are, indeed, pine, hi-noki cypress, and Chinese juniper, with pine occupying a particularly high position. The shin thus has a double function: to represent the season or month of the year and to serve as the structural pillar for the entire arrangement. In contrast to the role of seasonal plants in waka, which draw their associations from a wide range of textual sources, rikka depends on the physical shape and strength of the shin. Wisteria (fuji), for example, is a major late-spring—early-summer flower in classical poetry, but it is avoided as a shin since its branches droop and twist. As the Sendenshō indicates, however, wisteria can be used as a soe in a summer arrangement.11

Rikka is usually intended to encapsulate nature at large and bring it close, so it can be enjoyed. In this sense, it is similar to the rock-and-sand garden, which also represents high mountains, rivers, or distant seas in miniature or in a small space close to the inhabitant of the residence. Like kare-sansui, it makes use of the mitate technique of bringing distant landscapes within easy reach. The Sendenshō in fact makes a comparison between “setting up flowers” (hana o tateru) in a flower arrangement and constructing a rock garden: “When setting up a branch in a grass-flower vase, one should do it as if one were planting a tree in a garden; first, one should set up the center [shin] and then add the appropriate grasses at the base.”12 The “Enpekiken-ki” (Record of Enpekiken, 1675), a personal essay by Enpekiken (Kurokawa Dōyū [d. 1691], a doctor and historian), notes:

Originally rikka, standing-flower arrangement, came from the art of gardening [sakutei]. Sōami and Monami of the Sōrin-ji Temple in Hi-gashi-yama also constructed gardens. The garden in the Jōdo-ji [Pure Land Temple] is Sōami’s. It is from there that he began to work on the idea of rikka. The horizontal sand vase [sunamono] is an abbreviated representation of an island. The rikka reflects the mountains and rivers.13

Both Mon’ami (d. 1517), a Jishū (Time Sect) priest and cultural assistant (dōbōshū) to the Muromachi shogun Ashikaga Yoshitane, and Sōami (d. 1525), a dōbōshū and noted ink painter, were rikka artists.14 A subgenre of rikka, the sunamono (suna-no-mono) is designed to look like a small island, a common feature of Japanese rock-and-sand gardens, and to create the perspective of a garden up close, as opposed to the standard rikka, which represents a distant view of mountains and rivers.

The term “art of the flower” (kadō) is misleading, since the overall function of rikka is not to focus on the flower, as in a bouquet of roses, but to recreate the basic elements of nature (tree, grass, flower, river, mountain, waterfall, sky). An arrangement can evoke a wilderness or natural landscape. The preface to the Ikenobō Sen’ō kuden) for example, notes that the foremost function of the flower arrangement “is to express within a room the wild fields and mountains and the water’s edge as they exist outdoors.” The preface maintains that “with a little water and a short branch, one can represent a spectacular scene with many rivers and mountains, a beautiful scene of eternal changes amid the ephemeral.”15 In a typical rikka, the branch of the tree (shaped and held in place by pins) represents a mountain, the vase suggests a river, and the grasses at the bottom indicate wild fields, allowing the vastness of nature to be represented in a single vase. An arrangement can also suggest a more intimate scene. The Sendenshō, for example, includes instructions for such landscapes as “a fresh spring amid a wild field,” “flowers in the shadow of a giant rock,” and “flowers in a wild field blown by wind.”16

As noted in the Rikka imayō sugata (Modern Shape of Standing Flowers, 1688), an arrangement can also be highly symbolic and abstract. It can represent Mount Sumeru (Jp. Shumisen)—in Buddhist lore, a high mountain that symbolizes the center of the universe—a buddha (Skt. Tathagata), a bodhisattva, or the Buddhist cosmos.17 A rikka even can be flowerless, as in a display by Fushunken Senkei, a noted rikka professional active in the Gen-roku era (1688–1704), in which pine branches were the center, the augmentation, and the base. In a surprising reversal, the branches suggested blossoming flowers.

Gift Wrapping and Ritual Efficacy

As a one-time act or performance, rikka, like waka, was a means of everyday communication (of offering greetings, congratulations, condolences, and so forth) and had to be polite and subtle. In Japan, gifts are almost invariably wrapped, making them indirect and thus polite. Representations of nature both in poetry and in arts such as flower arrangement similarly became a way to make a message suggestive, cultured, and elegant. For example, one of the primary functions of the hokku, the opening verse in a renga sequence, was to greet the host of a poetry gathering. The seasonal word (kigo) marked the occasion (season) and the place. Typically, in waka or hokku, a natural image (such as a flower or a bird) served as a symbol for the host or the person being honored. Such poems used representations of nature to initiate or reaffirm social and political relations and to offer praise, prayer, and consolation to the addressee, sometimes including the spirits of the dead. The tea ceremony (chanoyu) and standing-flower arrangement were similarly used to establish and cement social relations. As such, they had to show respect and properly address the other party (whether a guest, a host, a military leader, or a member of the aristocracy). A poem offered or exchanged on such an occasion was part of a performative process in which the calligraphy and the paper (color, texture, and design) played a key role. All three elements (calligraphy, paper, and text) had to be appropriate to the season, the place, and the social position of the participants. Today, it is considered proper etiquette in Japan to begin all personal letters with an observation about the present phase of the season. This custom, which is taught in school and begins very early in Japan, creates an elegant greeting, with the seasonal reference becoming the epistolary version of the seasonal word in haiku.

Many of the screen paintings (byōbu-e) of the Heian and medieval periods were prepared as gifts to mark auspicious occasions, such as birthdays, weddings, and housewarmings (for example, the entrance of a daughter of a powerful minister from the northern Fujiwara clan into the imperial harem), and were given by one aristocrat to another or, in the medieval period, by one provincial warlord to another on important political or social occasions. Through their natural and seasonal iconography, these paintings indicated the pedigree, social status, and power of the giver and the importance of the recipient. For example, screen paintings and furniture designs alluding to the “Hatsune” (The First Song of the Warbler) chapter in The Tale of Genji, which marks the beginning of spring, were a favorite wedding gift or dowry in the Muromachi and Edo periods because of the chapter’s auspicious topoi (New Year and early spring) and association with courtly refinement.

A flower arrangement could be an offering (for example, to a god portrayed in a hanging scroll), a greeting from a host to a guest, a salute to the seasonal moment, and/or part of a social occasion or religious ritual. As the rikka treatises point out, pine covered with wisteria symbolized harmony between man and woman; pine, bamboo, and plum branch expressed congratulations; and the sacred lily (omoto  ; literally, “ten-thousand-year green”) represented continuity over generations—all associations that continue to be maintained. Chōbunsai Eishi’s (1756–1829) print Shinnen no iwai (Celebration of the New Year) shows women preparing auspicious flowers, such as narcissus (suisen), a winter and New Year flower; pheasant’s eye (fukujusō; literally, “wealth and felicity flower”); and sacred lily.18 The important role of rikka in annual observances is indicated in the list of appropriate shin for the Five Sacred Festivals (Gosekku) in the Ikenobō Senō kuden:

; literally, “ten-thousand-year green”) represented continuity over generations—all associations that continue to be maintained. Chōbunsai Eishi’s (1756–1829) print Shinnen no iwai (Celebration of the New Year) shows women preparing auspicious flowers, such as narcissus (suisen), a winter and New Year flower; pheasant’s eye (fukujusō; literally, “wealth and felicity flower”); and sacred lily.18 The important role of rikka in annual observances is indicated in the list of appropriate shin for the Five Sacred Festivals (Gosekku) in the Ikenobō Senō kuden:

Third day of the First Month |

Plum, narcissus, marigold |

Third day of the Third Month |

Peach, willow, yellow kerria |

Fifth day of the Fifth Month | Bamboo, sweet flag |

Seventh day of the Seventh Month |

Bellflower (kikyō), lychnis (sennō) |

Ninth day of the Ninth Month |

Chrysanthemum, cockscomb |

Each of these plants had a ritual function—such as dispelling evil elements (sweet flag) at the Tango Festival and promising long life (chrysanthemum) at Chōyō—appropriate to the observance.

The social function of rikka is also made evident in a long list of special occasions for flower arrangement in the Sendenshō:

Flowers for coming of age (genpuku no hana)

Flowers for when a person becomes a priest (hōshi nari no hana)

Flowers for when a child begins to speak (shonin nado mōsu toki no hana)

Flowers for going off to battle (shutsujin no hana)

Flowers for a new dwelling (watamashi no hana)

Flowers for praying to gods and buddhas (kitō no hana)20

The Sendenshō goes on to note that “flowers for when a child begins to speak” should not have thorns that could catch on the long sleeves or hem of the clothes and should have especially bright colors (implicitly to match the beauty of the child). When preparing “flowers for going off to battle,” one should not use camellia, maple, azalea (tsutsuji), or other plants whose flowers or leaves wither or scatter easily. “Flowers for a new dwelling” should not include anything that is red, which suggests fire. When it comes to “flowers for praying to gods and buddhas” to cure illness, one should not use carnation or pink (tokonatsu), a perennial whose name (literally, “everlasting summer”) would be inauspicious under such a circumstance. In similar fashion, the Ikenobō Sen’ō kuden lists plants that should be used on auspicious occasions (such as pine, bamboo, camellia, and willow) and those that should not be used on auspicious occasions, such as plants with four colors or four leaves, which evoke the word “four” (shi), a homonym with the word “death” (shi).21

Ikebana—like waka, renga, haikai (popular linked verse), and chanoyu—is best defined as a performance art; once the occasion is over, the flower arrangement has fulfilled its primary function. The Kan’ei era witnessed a sudden boom in the publication of secret treatises and illustrated texts on rikka that served as records of one-time performances, much like the records of tea ceremonies that appeared in the Tenbun era (1532–1555) and the haikai diaries of the Edo period. The original contexts of these performances, which were often social, religious, or political, could never be fully re-created. But they served as guides and lessons for future performances and transmitted knowledge and expertise from teachers to disciples.22

The Thrown-in Flower and the Tea Ceremony

Under the impact of Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591), the tea ceremony (chanoyu) evolved from a highly formal Chinese-style ritual, with complex rules, to “rustic tea” (wabicha), which reduced the size of the tearoom from the parlor (shoin) to a very small space. The wabicha teahouse took the form of a miniature grass hut (sōan), thereby re-creating the mountain village (yamazato), which was a major topos in medieval waka and renga, in the middle of the city. Following a similar historical arc, the palace-style (shinden-zukuri) garden evolved into the enclosed shoin garden and then further shrank into the rock-and-sand garden (kare-sansui) and the sand-and-stone landscape on a tray (bonseki)23 The small form was not necessarily easier to approach, often becoming increasingly complex, but it was clearly more compact.

A different kind of “slimming down” occurred in the transition from renga to haikai, which relaxed the complex rules of renga and became significantly shorter—from hundred- or thousand-verse to fifty- or thirty-six-verse sequences—eventually focusing on the seventeen-syllable hokku. There was also a movement in flower arrangement from the formal and highly regulated standing-flower (rikka) form to the relaxed thrown-in-flower (nageire or nageirebana) form, which maintained many of the social and cultural functions of rikka, but presented them in a much smaller, simplified, casual, and accessible manner.

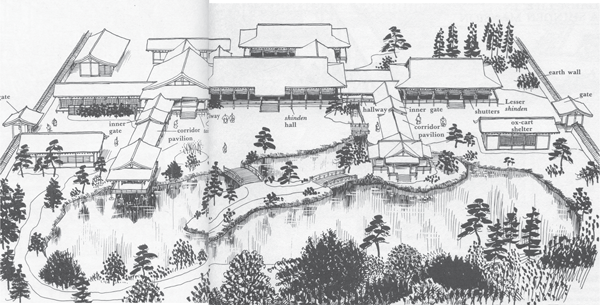

This movement from formal to informal and from heavy to light versions of performance was often articulated by their practitioners by using the calligraphic terms shin (formal style), gyō (cursive style), and so (abbreviated style; literally, “grass style”). The Sashibana keiko hyakushu (Hundred Poems on Practicing Ikebana, 1768), for example, compares rikka to shin, su-namono (sand vase arrangement) to gyō, and nageire to so.24 In contrast to rikka, which was highly regulated and involved great effort to shape and bend the tree and flower branches (using pins and wire), nageire was formed with only one or two flowers. In the latter half of the sixteenth century, when Sen no Rikyū established the understated tea ceremony (wabicha), he also adapted the thrown-in-flower style, calling it the tea flower (chabana). Typically, the host removes the hanging scroll from the alcove (tokonoma) and replaces it with a simple flower arrangement as an offering to his guest or guests (figure 14). The objective is to display a taste for nature appropriate to a miniature retreat and to articulate the seasonal moment.

TEAROOM AND A FLOWER IN THE ALCOVE

The understated-tea-style (wabicha) tearoom was much smaller than the parlor in a shoin-style residence, and the alcove was similarly reduced in size. The alcove usually displayed a standing-flower arrangement and/or a hanging scroll with a painting or calligraphy. Following the wabicha style, this alcove, in the Shinju-an (Pearl Hut) in the Daitoku-ji temple complex in Kyoto, is decorated with a simple thrown-in-flower arrangement in a plain vase hung from the wall. The bud of the morning glory faces the guest (seated on the right), who watches it bloom in the course of the tea ceremony. (From Tamagami Takuya, Hayashiya Tatsusa-burō, and Yamane Yūzō, eds., Ikebana no bunkashi, vol. 3 of Zusetsu ikebana taikei [Tokyo: Kadokawa shoten, 1970], fig. 29. Courtesy of Kadokawa shoten)

By the Genroku era, the popularity of nageire had grown to the point where it became independent of the tea ceremony and inspired its first treatise, Nageirebana denshō (Secret Transmission of the Thrown-in-Flower Arrangement, 1684). Nageire eliminated the triad display (incense burner, flower vase, and crane-and-turtle candle lamp) before a Buddhist image, with its religious and ceremonial implications. It also reduced the complex system of seven or nine branch positions in rikka to the basic three of center (shin), augmentation (soe), and base (tai). But the thrown-in-flower style did retain certain fundamental elements of rikka: the tree branches (ki-mono); the grasses (kusa-mono); and the “two-way things” (tsuyo-mono), which could be regarded as either trees or grasses. The smaller, lighter, and simpler thrown-in-flower style, which was more appropriate to the small alcoves in the houses of urban commoners and farmers, eventually spread throughout Edo society and appeared in a variety of formats, including the “nailed flower” (kake-hana), a small vase hung from a wall or pillar by a nail; the “suspended flower” (tsurihana), a small vase (in the shape of the moon, a boat, a basket, and the like) suspended from the ceiling; and the flower arrangement placed on the staggered shelves (chigaidana) of a parlor.

When a flower arrangement was combined with a hanging scroll in the alcove in either rikka or nageire, the two had to harmonize. The Sendenshō notes that in flower arrangement and painting, “a willow should be matched with a Kannon bodhisattva painting; cherry (or plum) with a Tenjin [Suga-wara no Michizane (845–903)] god portrait; bamboo with a tiger; pine with a dragon; an old tree with an ancient person. … Waterside flowers and plants or trees in fields and mountains should be matched with a landscape painting.”25 The plum blossom was a symbol of Michizane, a major poet of the Heian period; the strength of bamboo matched that of the tiger; and pine reflected the longevity and good fortune of the dragon. A similar connection existed between the flower arrangement and the enclosed garden outside the parlor, viewed through an open door or a window. The Nageirebana denshō observes that the flower arrangement should not duplicate the garden; instead, the flower arrangement, the room, and the garden should complement one another.

The tea ceremony (chanoyu) connected these various forms through a semi-ritualized presentation of tea, sweets (wagashi), and sometimes food. It displayed different media in an alcove (flower arrangement, painting, Chinese and Japanese poetry, and calligraphic fragments of literary and religious texts) and made use of ceramics, lacquerware, metalware, and hanging scrolls—not to mention the garden outside the teahouse. All these elements were arranged in order to harmonize with the seasonal moment. For example, a tea ceremony often was held after an excursion to view the cherry blossoms. According to the Rikyū hyakushu (Rikyūs One Hundred Poems, 1642), one of the hundred-poem sequences on tea ceremony principles attributed to Sen no Rikyū, a painting of flowers should not be displayed or a flower arrangement should not be made with cherry blossoms.26 Instead, the season should be suggested, for example, by a poem or a calligraphic text on a hanging scroll that implies spring. The moment could also be reflected in the arrangement of the small vegetable and fish dishes (kai-seki) or the ceramic plates for side dishes (mukōzuke; literally, “far-side dishes”). For example, Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743), a noted Rimpa ceramics master, made mukōzuke dishes such as the Colored Painting of the Tatsuta River (Miho Museum, Kyoto), which represents the poetic essence of autumn. As we will see, the tea ceremony also involved the presentation, naming, and consumption of Japanese sweets that embodied the season. In short, chanoyu, which was intended to develop cultural sensitivity as well as provide the opportunity for social bonding and private entertainment, raised the presentation of tea and food to the level of art, fusing textual and material culture to create a tactile symphony of the seasonal moment. In this sense, the tea ceremony, which developed in the middle of the metropolis as a formalized and temporary mini-retreat from urban life, epitomizes the development of secondary nature in Japan, bringing the interiorization and representation of nature and the seasons to one of its historical heights.

In the Edo period, waka and ikebana were considered indispensable for the education of a daughter from a high-ranking samurai or wealthy merchant family. Standing-flower arrangement (rikka) as a woman’s accomplishment was first practiced—along with the arts of calligraphy, koto (zither-like instrument), poetry, and dance—by high-ranking courtesans in the pleasure quarters.27 For them, flower arrangement was essential to entertaining customers, and their skill in this art is illustrated in Yoshiwara no tei (A Scene from Yoshiwara, ca. 1688), a black-and-white woodblock print by Hi-shikawa Moronobu (1618–1694), and a scene from Seirō bijin awase sugata kagami (A Mirror of Beautiful Women in the Pleasure Quarters, 1776), a four-season guide to the best courtesan houses in Yoshiwara by Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) and Katsukawa Shunshō (1727–1792) (figure 15). The art of ikebana then spread to the wives and daughters of urban commoners, for whom it became an essential means to acquire culture.

The Onna chōhōki (Treasures for Women, 1692, revised 1847), a widely used etiquette manual and guide for women, notes that a woman should be accomplished in rikka, incense contest, the tea ceremony, and linked verse (renga-haikai). As Onna chōhōki and Nan chōhōki (Treasures for Men, 1693), a popular etiquette guide for men, indicate, both men and women were supposed to learn chanoyu and rikka as part of their cultural, social, and moral training, but the tea ceremony became primarily a male occupation, while women gravitated to flower arrangement, particularly in the form of seika (shōka; literally, “live flower”), a style that began in the mid-Edo period and simplified rikka for popular use. Seika came to be regarded as an indispensable part of a girl’s education, a view that continued into the Meiji period (1868–1912) when, in 1887, the government officially made kadō (way of the flower) part of women’s public education.

The ukiyo-e developed into the multicolor print (nishiki-e) in the latter half of the eighteenth century, from around 1765, which coincides with the time that ikebana became extremely popular among urban commoners in Edo. These woodblock prints portray a range of women (from daughters of urban commoners to famous courtesans of the pleasure quarters) with a wide variety of flower vases in different places (sitting in an alcove, on a veranda, or on a tatami floor; hanging from a ceiling or wall). The styles of ikebana differ widely, from rikka (standing flower) to nageire (thrown-in flower) to the various competing styles of seika. The women are sometimes shown practicing ikebana—taking a vase out of a box, working with an ikebana teacher, or cutting and arranging the flowers—as in Kitao Shige-masa’s Bijin hana-ike (Beautiful Women Arranging Flowers, eighteenth century).28 Late-eighteenth-century ukiyo-e such as Chōbunsai Eishi’s series “Furyu gosekku” (Elegant Five Sacred Festivals, ca. 1794–1795) and hanging scrolls such as Katsukawa Shunshō’s Fujo fūzoku jūnikagetsu zu (Women’s Customs in the Twelve Months, ca. 1781–1790) show women with the flowers associated with two of the Five Sacred Festivals (see figures 21 and 23).

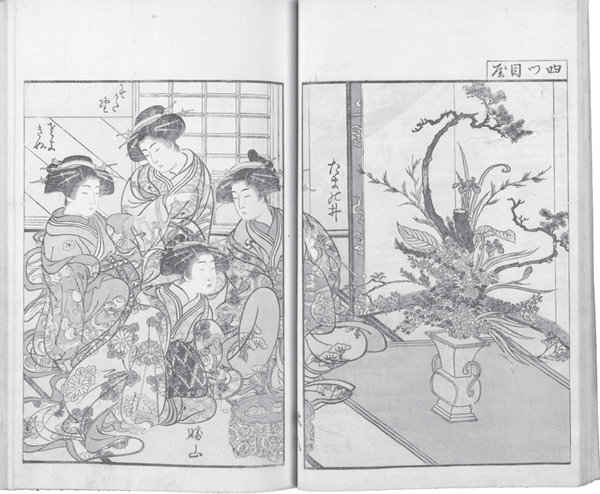

HIGH-RANKING COURTESANS WITH A FLOWER ARRANGEMENT

Kitao Shigemasa and Katsukawa Shunshō’s A Mirror of Beautiful Women in the Pleasure Quarters (Seirō bijin awase sugata kagami, 1776) depicts high-ranking courtesans engaged in cultural activities during the four seasons. This scene shows four courtesans—Tamanoi, Katsuyama, Sugatano, and Sayoginu—with an elaborate, autumn standing-flower (rikka) arrangement: a pine branch for the main axis and smaller branches, autumn grasses, and flowers for the triangular base. The rikka mirrors the beauty of the courtesans. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Spencer Collection, Sorimachi 439, digital ID 1504263)

Many of the ukiyo-e are serial prints (one for each month or one for each season), in which the seasons are contrasted with one another, as in Heian-period four-season screen paintings (shikj-e) and Kamakura-period twelve-month paintings (tsukinami-e). But unlike the four-season and twelve-month paintings, which depict landscapes, these ukiyo-e are bijinga (portraits of beautiful people) that portray women indoors, concentrating on their clothing, particularly the colorful kosode (kimono) designs that complement the flower displays. As Kobayashi Tadashi has argued, the prominent presence of arranged flowers in these bijinga enabled ukiyo-e artists to interiorize the earlier tradition of twelve-month screen paintings, which represented nature and flowers from the garden or the hills, bringing “nature” into a commoner residence.29

The Return of the Flower Garden

For most of Japanese history, the cultivation of flowers was part of elite culture. But from the early Edo period, flower gardening (growing flowers and plants for recreation and aesthetic purposes) also became very popular among both samurai and urban commoners. Three early Tokugawa sho-guns—Ieyasu (1542–1616), Hidetada (1579–1632), and Iemitsu (1604–1651)—were great lovers of planted trees, and the provincial warlords (daimyo) and bannermen imitated them. The camellia rage of the Kan’ei era reflected the interests of Hidetada, Iemitsu, and Retired Emperor GoMizunoo (1596–1680; r. 1611–1629). After the Meireki fire in 1657, which destroyed much of Edo, powerful samurai, temples, and shrines hired gardeners to reconstruct or develop new gardens, which became very popular. The rise of botany and the study of nature for medicinal purposes (honzōgaku) at this time also spurred the boom in flower gardening.

In the Heian and medieval periods, the most highly valued flowers, such as plum and cherry, were those of trees that bloomed in the mountains or on the grounds of shrines or temples and that had religious significance. There was a gradual shift in the Edo period from these tree flowers—such as plum, cherry, mandarin orange, and camellia—toward such grass flowers as Japanese woodland primrose (sakurasō), sweet flag (shōbu), and chrysanthemum. The azalea (tsutsuji), a low-bush flower ideal for gardens, became popular in the Genroku era, and a craze for chrysanthemums developed in the Meiwa era (1764–1772). The gradual shift to grass flowers, which could be easily grown in private gardens, is perhaps best exemplified by the increasing popularity of the chrysanthemum, which appears in many women-and-ikebana ukiyo-e from the late eighteenth century onward. Somei in Edo (present-day Komagome, Tokyo) became famous for its many garden shops that produced various types of azalea, rhododendron, and chrysanthemum, as well as the Somei-Yoshino cherry tree, which became the representative cherry tree in modern Japan (figure 16). This new gardening culture, which led to the proliferation of garden clubs, emerged at the same time that urban commoners were participating in more public “nature” activities or forms of entertainment, such as cherry-blossom viewing (hana-mi) and making chrysanthemum dolls (kiku ningyō).30 The spread of gardening had a profound impact on the representation of nature, particularly flowers and trees. Together with flower arrangement and the tea ceremony, which emerged as forms of “natural” retreat in the city, it brought “nature” into the large metropolis (such as Edo and Osaka) and made it an integral part of domestic, everyday commoner life.

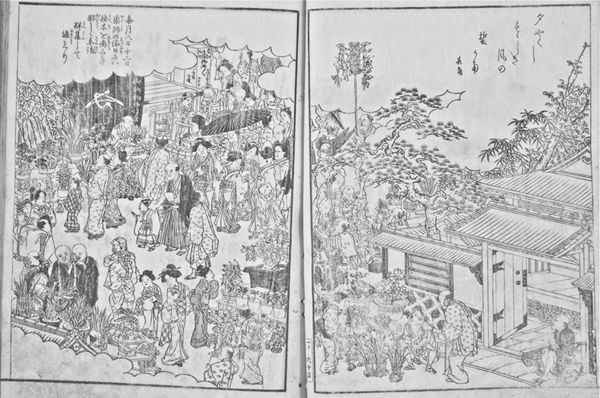

GARDEN SHOP IN EDO

The popularity of ikebana in Edo was paralleled by the growth of gardening as a pastime pursued by both powerful warlords and urban commoners. This illustration by Hasegawa Settan (1778–1843) in Illustrated Guide to Famous Places in Edo (Edo meisho zue, 1834–1836), edited by Saitō Gesshin (1804–1878) and others, depicts the open market for vendors of plants and gardening implements, held on the eighth and twelfth days of each month, at the Hall of the Healing Buddha (Yakushidō) in Kayabachō. A wide range of cultivated plants, including bonsai, is being admired by men and women of all ages and social positions. (Courtesy of Waseda University Library, Special Collection, Tokyo)

The emergence of a complex secondary nature in the city occurred in at least three fundamental ways in the long span from the eighth through the sixteenth century. First, it appeared most concretely in the form of poetry (especially waka and renga), which developed a highly codified set of seasonal associations that became the basis for daily and ritualistic communication and that functioned as an elegant, indirect, and polite means of address, with various levels of overtones. Second, the codification of the seasons and of nature spread to a wide variety of visual and material forms: dress, screen painting, scroll painting, and decorative arts such as ceramics and furniture. Some of the genres, such as the bird-and-flower paintings (kachōga) that would become very popular from the medieval period, had their precedents in China and developed their own native variations. Third, Japanese architecture, with its removable or movable walls and doors, developed a strong sense of spatial continuity between the interior and the exterior, especially between the living quarters and the garden, first in the pal-ace-style (shinden-zukuri) residence of the Heian period and later in the parlor-style (shoin-zukuri) residence, which became the archetype for the Japanese house. The Muromachi-period arts of the alcove (tokonoma) in the parlor further reinforced this sense of continuity between the human and natural spheres. Furthermore, in the Edo period, new forms emerged that were more accessible to urban commoners—such as haikai, ikebana (especially seika), and landscape woodblock prints—and maintained many of the social and ritualistic functions that waka and screen paintings had held for the aristocracy.

These capital-centered representations and reconstructions of nature would intersect with and be enriched by provincial, commoner-based views of nature and landscape that appeared in mythic, folk, and popular literature.