CHAPTER VIII

PHILOSOPHICAL CONSEQUENCES

1. PRE-SENSORY EXPERIENCE AND PURE EMPIRICISM

8.1. If the account of the determination of mental qualities which we have given is correct, it would mean that the apparatus by means of which we learn about the external world is itself the product of a kind of experience (5.1–5.16). It is shaped by the conditions prevailing in the environment in which we live, and it represents a kind of generic reproduction of the relations between the elements of this environment which we have experienced in the past; and we interpret any new event in the environment in the light of that experience. If this conclusion is true, it raises necessarily certain important philosophical questions on which in this last chapter we shall attempt some tentative observations.

8.2. These consequences arise mainly from the rôle which we have assigned to the action of the pre-sensory experience or ‘linkages’ in determining the sensory qualities. Especially the elimination of the hypothetical ‘pure’ or ‘primary’ core of sensations, supposed not to be due to earlier experience, but either to involve some direct communication of properties of the external objects, or to constitute irreducible mental atoms or elements, disposes of various philosophical puzzles which arise from the lack of meaning of those hypotheses.

8.3. According to the traditional view, experience begins with the reception of sensory data possessing constant qualities which either reflect corresponding attributes belonging to the perceived external objects, or are uniquely correlated with such attributes of the elements of the physical world. These sensory data are supposed to form the raw material which the mind accumulates and learns to arrange in various manners. The theory developed here challenges the basic distinction implied in that conception: the distinction between sensory perception of given qualities and the operations which the intellect is supposed to perform on these data in order to arrive at an understanding of the given phenomenal world (5.19, 6.44).

8.4. According to our theory, the characteristic attributes of the sensory qualities, or the classes into which different events are placed in the process of perception, are not attributes which are possessed by these events and which are in some manner ‘communicated’ to the mind; they are regarded as consisting entirely in the ‘differentiating’ responses of the organism by which the qualitative classification or order of these events is created; and it is contended that this classification is based on the connexions created in the nervous system by past linkages. Every sensation, even the ‘purest’, must therefore be regarded as an interpretation of an event in the light of the past experience of the individual or the species.

8.5. The process of experience thus does not begin with sensations or perceptions, but necessarily precedes them: it operates on physiological events and arranges them into a structure or order which becomes the basis of their ‘mental’ significance; and the distinction between the sensory qualities, in terms of which alone the conscious mind can learn about anything in the external world, is the result of such pre-sensory experience. We may express this also by stating that experience is not a function of mind or consciousness, but that mind and consciousness are rather products of experience (2.50).

8.6. Every sensory experience of an event in the external world is therefore likely to possess ‘attributes’ (or to be in a manner distinguished from other sensory events) to which no similar attributes of the external events correspond. These ‘attributes’ are the significance which the organism has learnt to assign to a class of events on the basis of the past associations of events of this class with certain other classes of events. It is only in so far as the nervous system has learnt thus to treat a particular stimulus as a member of a certain class of events, determined by the connexions which all the corresponding impulses possess with the same impulses representing other classes of events, that an event can be perceived at all, i.e., that it can obtain a distinct position in the system of sensory qualities.

8.7. If the distinctions between the different sensory qualities of which our conscious experience appears to be built up are thus themselves determined by pre-sensory experiences (linkages), the whole problem of the relation between experience and knowledge assumes a new complexion. So far as experience in the narrow sense, i.e., conscious sensory experience, is meant, it is then clearly not true that all that we know is due to such experience. Experience of this kind would rather become possible only after experience in the wider sense of linkages has created the order of sensory qualities—the order which determines the qualities of the constituents of conscious experience.

8.8. Sense experience therefore presupposes the existence of a sort of accumulated ‘knowledge’, of an acquired order of the sensory impulses based on their past co-occurrence; and this knowledge, although based on (pre-sensory) experience, can never be contradicted by sense experiences and will determine the forms of such experiences which are possible.

8.9. John Locke’s famous fundamental maxim of empiricism that nihil est in intellectu quod non antea fuerit in sen su is therefore not correct if meant to refer to conscious sense experience. And it does not justify the conclusion that all we know (quod est in intellectu) must be subject to confirmation or contradiction by sense experience. From our explanation of the formation of the order of sensory qualities itself it would follow that there will exist certain general principles to which all sensory experiences must conform (such as that two distinct colours cannot be in the same place)—relations between the parts of such experiences which must always be true.

8.10. A certain part at least of what we know at any moment about the external world is therefore not learnt by sensory experience, but is rather implicit in the means through which we can obtain such experience; it is determined by the order of the apparatus of classification which has been built up by pre-sensory linkages. What we experience consciously as qualitative attributes of the external events is determined by relations of which we are not consciously aware but which are implicit in these qualitative distinctions, in the sense that they affect all that we do in response to these experiences.

8.11. All that we can perceive is thus determined by the order of sensory qualities which provides the ‘categories’ in terms of which sense experience can alone take place. Conscious experience, in particular, always refers to events defined in terms of relations to other events which do not occur in that particular experience.1

8.12. We thus possess ‘knowledge’ about the phenomenal world which, because it is in this manner implicit in all sensory experience, must be true of all that we can experience through our senses. This does not mean, however, that this knowledge must also be true of the physical world, that is, of the order of the stimuli which cause our sensations. While the conditions which make sense perception possible—the apparatus of classification which treats them as similar or different—must affect all sense perception, it does not for this reason also govern the order of the events in the physical world.

8.13. It requires a deliberate effort to divest oneself of the habitual assumption that all we have learned from experience must be true of the external (physical) world.2 But since all we can ever learn from experience are generalizations about certain kinds of events, and since no number of particular instances can ever prove such a generalization, knowledge based entirely on experience may yet be entirely false. If the significance which a certain group of stimuli has acquired for us is based entirely on the fact that in the past they have regularly occurred in combination with certain other stimuli, this may or may not be an adequate basis for a classification which will enable us to make true predictions. We have earlier (5.20–5.24) given a number of reasons why we must expect that the classifications of events in the external world which our senses perform will not strictly correspond to a classification of these events based solely on the similarity or the differences of their behaviour towards each other.

8.14. While there can thus be nothing in our mind which is not the result of past linkages (even though, perhaps, acquired not by the individual but by the species), the experience that the classification based on the past linkages does not always work, i.e., does not always lead to valid predictions, forces us to revise that classification (6.45–6.48). In the course of this process of reclassification we not only establish new relations between the data given within a fixed framework of reference, i.e., between the elements of given classes: but since the framework consists of the relations determining the classes, we are led to adjust that framework itself.

8.15. The reclassification, or breaking up of the classes formed by the implicit relations which manifest themselves in our discrimination of sensory qualities, and the replacement of these classes by new classes defined by explicit relations, will occur whenever the expectations resulting from the existing classification are disappointed, or when beliefs so far held are disproved by new experiences. The immediate effects of such conflicting experiences will be to introduce inconsistent elements into the model of the external world; and such inconsistencies can be eliminated only if what formerly were treated as elements of the same class are now treated as elements of different classes (5.72).

8.16. The reclassification which is thus performed by the mind is a process similar to that through which we pass in learning to read aloud a language which is not spelled phonetically. We learn to give identical symbols different values according as they appear in combination with different other symbols, and to recognize different groups of symbols as being equivalent without even noticing the individual symbols.

8.17. While the process of reclassification involves a change of the frame of reference, or of what is a priori true of all statements which can be made about the objects defined with respect to that frame of reference, it alters merely the particular presuppositions of all statements, but does not change the fact that such presuppositions must be implied in all statements that can be made. In fact, far from being diminished, the a priori element will tend to increase as in the course of this process the various objects are increasingly defined by explicit relations existing between them.

8.18. The new experiences which are the occasion of, and which enter into, the new classifications or definitions of objects, is necessarily presupposed by anything which we can learn about these objects and cannot be contradicted by anything which we can say about the objects thus defined. There is, therefore, on every level, or in every universe of discourse, a part of our knowledge which, although it is the result of experience, cannot be controlled by experience, because it constitutes the ordering principle of that universe by which we distinguish the different kinds of objects of which it consists and to which our statements refer.

8.19. The more this process leads us away from the immediately given sensory qualities, and the more the elements described in terms of these qualities are replaced by new elements defined in terms of consciously experienced relations, the greater becomes the part of our knowledge which is embodied in the definitions of the elements, and which therefore is necessarily true. At the same time the part of our knowledge which is subject to control by experiences becomes correspondingly smaller.

8.20. This progressive growth of the tautological character of our knowledge is a necessary consequence of our endeavour so to readjust our classification of the elements as to make statements about them true. We have no choice but either to accept the classification effected by our senses, and in consequence to be unable correctly to predict the behaviour of the objects thus defined; or to redefine the objects on the basis of the observed differences in their behaviour with respect to each other, with the result that not only the differences which are the basis of our classification become necessarily true of the objects thus classified, but also that it becomes less and less possible to say of any particular sensory object with any degree of certainty to which of our theoretical classes it belongs.

8.21. This difficulty does not become too serious so long as we merely redefine a particular object in relational terms. But as we continue this process of reclassification, those other objects must in turn also be redefined in a similar manner. In the course of this process we are soon forced to take into account not only relations existing between a given object and other objects which are actually observed in conjunction with the former, but also relations which have existed in the past between that and other objects, and even relations which can be described only in hypothetical terms: relations which might have been observed between this and other objects in circumstances which did not in fact exist and which, if they had existed, would not have left the identity of the object unchanged.

8.22. Several chemical substances may, e.g., be completely indistinguishable to the senses so long as they remain in their given state. The reason why chemistry classifies them as different substances is that in certain circumstances and in combination with certain other substances they will ‘react’ differently. But most of these chemical reactions involve a change in the character of the substance, so that the identical quantity of a given substance, which has been tested for the reaction which is the basis of its classification, cannot be available after it has been established to which class it belongs. Only by such unverifiable assumptions as that the quantity of the substance from which we have drawn the sample is completely homogeneous, so that what we have found out about various samples applies also to the rest, can we arrive at the conclusion that the particular sensory object belongs to a definite theoretical class.

8.23. The sense data, or the sensory qualities of the objects about which we make statements, thus are pushed steadily further back; and when we complete the process of defining all objects by explicit relations instead of by the implicit relations inherent in our sensory distinctions, those sense data disappear completely from the system. In the end the system of explicit definitions becomes both all-comprehensive and self-contained or circular; all the elements in the universe are defined by their relations to each other, and all we know about that universe becomes contained in those definitions. We should obtain a self-contained model capable of reproducing all the combinations of events which we can observe in the external world, but should have no way of ascertaining whether any particular event in the external world corresponded to a particular part of our model.

8.24. Science thus tends necessarily towards an ultimate state in which all knowledge is embodied in the definitions of the objects with which it is concerned; and in which all true statements about these objects therefore are analytical or tautological and could not be disproved by any experience. The observation that any object did not behave as it should could then only mean that it was not an object of the kind it was thought to be. With the disappearance of all sensory data from the system, laws (or theories) would no longer exist in it apart from the definitions of the objects to which they applied, and for that reason could never be disproved.

8.25. Such a completely tautological or self-contained system of knowledge about the world would not be useless. It would constitute a model of the world from which we could read off what kind of events are possible in that world and what kind are not. It would often allow us, on the basis of a fairly complete history of a particular sensory object, to state with a high degree of probability that it fits into one and only one possible place in our model, and that in consequence it is likely to behave in a certain manner in circumstances which would have to be similarly described. But it would never enable us to identify with certainty a particular sensory object with a particular part of our model, or with certainty to predict how the former will behave in given circumstances.

8.26. A strict identification of any point of our theoretical model of the world with a particular occurrence in the sensory world would be possible only if we were in a position to complete our model of the physical world by including in it a complete model of the working of our brain (cf. 5.77–5.91)—that is, if we were able to explain in detail the manner in which our senses classify the stimuli. This, however, as will be shown in section 6 of this chapter, is a task which that same brain can never accomplish.

8.27. In conclusion of this section it should, perhaps, be emphasized that, in so far as we have been led into opposition to some of the theses traditionally associated with empiricism, we have been led to their rejection not from an opposite point of view, but on the contrary, by a more consistent and radical application of its basic idea. Precisely because all our knowledge, including the initial order of our different sensory experiences of the world, is due to experience, it must contain elements which cannot be contradicted by experience. It must always refer to classes of elements which are defined by certain relations to other elements, and it is valid only on the assumption that these relations actually exist. Generalization based on experience must refer to classes of objects or events and can have relevance to the world only in so far as these classes are regarded as given irrespective of the statement itself. Sensory experience presupposes, therefore, an order of experienced objects which precedes that experience and which cannot be contradicted by it, though it is itself due to other, earlier experience.

2. PHENOMENALISM AND THE INCONSTANCY OF SENSORY QUALITIES

8.28. If the classification of events in the external world effected by our senses proves not to be a ‘true’ classification, i.e. not one which enables us adequately to describe the regularities in this world, and if the properties which our senses attribute to these events are not objective properties of these individual events, but merely attributes defining the classes to which our senses assign them, this means that we cannot regard the phenomenal world in any sense as more ‘real’ than the constructions of science: we must assume the existence of an objective world (or better, of an objective order of the events which we experience in their phenomenal order) towards the recognition of which the phenomenal order is merely a first approximation. The task of science is thus to try and approach ever more closely towards a reproduction of this objective order—a task which it can perform only by replacing the sensory order of events by a new and different classification.3

8.29. By saying that there ‘exists’ an ‘objective’ world different from the phenomenal world we are merely stating that it is possible to construct an order or classification of events which is different from that which our senses show us and which enables us to give a more consistent account of the behaviour of the different events in that world. Or, in other words, it means that our knowledge of the phenomenal world raises problems which can be answered only by altering the picture which our senses give us of that world, i.e. by altering our classification of the elements of which it consists. That this is possible and necessary is, in fact, a postulate which underlies all our efforts to arrive at a scientific explanation of the world.

8.30. Any purely phenomenalistic interpretation of the task of science, or any attempt to reduce this task to merely a complete description of the phenomenal world, thus must break down because our senses do not effect such a classification of the different events that what appears to us as alike will also always behave in the same manner. The basic thesis of phenomenalism (and positivism) that ‘all phenomena are subject to invariable laws’ is simply not true if the term phenomenon is taken in its strict meaning of things as they appear to us.

8.31. The ideal of science as merely a complete description of phenomena, which is the positivist conclusion derived from the phenomenalistic approach, therefore proves to be impossible. Science consists rather in a constant search for new classes, for ‘constructs’ which are so defined that general propositions about the behaviour of their elements are universally and necessarily true. For this purpose these classes cannot be defined in terms of sensory properties of the particular individual events perceived by the individual person; they must be defined in terms of their relations to other individual events.

8.32. Such a definition of any class of events, in terms of their relations to other classes of events instead of in terms of any sensory properties which they individually possess, cannot be confined to the former, or even to all the events which together constitute the complete situation existing at a particular moment. The events referred to in the definition of those with which we have actually to deal have to be defined in a similar purely ‘relational’ manner. The ultimate aim of this procedure must be to define all classes of events exclusively in terms of their relations to each other and without any reference to their sensory properties. It has been well said that ‘for science an object expresses itself in the totality of relations possible between it and other objects.’4 We have already seen (8.24–8.25) that such a complete system of explanation would necessarily be tautological, because all that could be predicted by it would necessarily follow from the definitions of the objects to which it referred.

8.33. If the theory outlined here is correct, there exists an even more fundamental objection to any consistently phenomenalist interpretation of science. It would appear that not only are the events of the world, if defined in terms of their sensory attributes, not subject to invariable laws, so that situations presenting the same appearance to our senses may produce different results; but also that the phenomenal world (or the order of the sensory qualities from which it is built up) is itself not constant but variable, and that it will in some measure change its appearance as a result of that very process of reclassification which we must perform in order to explain it.

8.34. If it is true, as we have argued, that the ‘higher’ mental activities are merely a repetition at successive levels of processes of classification of essentially the same character as those by which the different sensory qualities have come to be distinguished in the first instance, it would seem almost inevitable that this process of reclassification will in some measure also affect the distinctions between the different sensory qualities from which it starts. The nature of the process by which the difference between sensory qualities are determined makes it probable that they will remain variable and that the distinctions between them will be modified by new experiences. This would mean that the phenomenal world itself would not be constant but would be incessantly changing in a direction to a closer reproduction of the relations existing in the physical world. If in the course of this process the sensory data themselves alter their character, the ideal of a purely descriptive science becomes altogether impossible.

8.35. That the sensory qualities which attach to particular physical events are thus in principle themselves variable5 is no less important even though we must probably regard them as relatively stable compared with the continuous changes of the scheme of classification in terms of which abstract thought proceeds, almost certainly in so far as the course of the life of the individual is concerned. But we should still have to consider more seriously than we are wont to do, what is amply confirmed by ordinary experience, namely that as a result of the advance of our explanation of the world we also come to ‘see’ this world differently, i.e. that we not merely recognize new laws which connect the given phenomena, but that these events are themselves likely to change their appearance to us.

8.36. Such variations of the sensory qualities attributed to given events could, of course, never be ascertained by direct comparisons of past and present sensations, since the memory images of past sensations would be subject to the same changes as the current sensations. The only possibility of testing this conclusion would be provided by experiments with discrimination such as have been suggested in the preceding chapter (7.38–7.51).

8.37. It deserves, perhaps, to be mentioned that, although the theory developed here was suggested in the first instance by the psychological views which Ernst Mach has outlined in his Analysis of Sensations and elsewhere, its systematic development leads to a refutation of his and similar phenomenalist philosophies: by destroying the conception of elementary and constant sensations as ultimate constituents of the world, it restores the necessity of a belief in an objective physical world which is different from that presented to us by our senses.6

8.38. Similar considerations apply to the views expounded on these matters by William James, John Dewey and the American realists and developed by Bertrand Russell. The latter’s view according to which ‘the stuff of the world’ consists of ‘innumerable transient particulars’ such as a patch of colour which is ‘both physical and psychical’ in fact is explicitly based on the assumption that ‘sensations are what is common to the mental and the physical world’, and that their essence is ‘their independence from past experience’. The whole of this ‘neutral monism’ seems to be based on entirely untenable psychological conceptions.7

8.39. Another interesting consequence following from our theory is that a stimulus whose occurrence in conjunction with other stimuli showed no regularities whatever could never be perceived by our senses (6.36). This would seem to mean that we can know only such kinds of events as show a certain degree of regularity in their occurrence in relations with others, and that we could not know anything about events which occurred in a completely irregular manner. The fact that the world which we know seems wholly an orderly world may thus be merely a result of the method by which we perceive it. Everything which we can perceive we perceive necessarily as an element of a class of events which obey certain regularities. There could be in this sense no class of events showing no regularities, because there would be nothing which could constitute them for us into a distinct class.

3. DUALISM AND MATERIALISM

8.40. Because the account of the determination of mental qualities which has been given here explains them by the operation of processes of the same kind as those which we observe in the material world, it is likely to be described as a ‘materialistic’ theory. Such a description in itself would matter very little if it were not for certain erroneous ideas associated with the term materialism which not only would prejudice some people against a theory thus described but, what is more important, would also suggest that it implies certain conclusions which are almost the opposite of those which in fact follow from it. In the true sense of the word ‘materialistic’ it might even be argued that our theory is less materialistic than the dualistic theories which postulate a distinct mind ‘substance’.

8.41. The dualistic theories are a product of the habit, which man has acquired in his early study of nature, of assuming that in every instance where he observed a peculiar and distinct process it must be due to the presence of a corresponding peculiar and distinct substance. The recognition of such a peculiar material substance came to be regarded as an adequate explanation of the process produced.

8.42. It is a curious fact that, although in the realm of nature in general we no longer accept as an adequate explanation the postulate of a peculiar substance possessing the capacity of producing the phenomena we wish to explain, we still resort to this old habit where mental events are concerned. The mind ‘stuff’ or ‘substance’ is a conception formed in analogy to the different kinds of matter supposedly responsible for the different kinds of material phenomena. It is, to use an old term in its literal sense, the result of a ‘hylomorphic’ manner of thinking. Yet in whatever manner we define substance, to think of mind as a substance is to ascribe to mental events some attributes for whose existence we have no evidence and which we postulate solely on the analogy of what we know of material phenomena.8

8.43. In the strict sense of the terms employed an account of mental phenomena which avoids the conception of a distinct mental substance is therefore the opposite of materialistic, because it does not attribute to mind any property which we derive from our acquaintance with matter. In being content to regard mind as a peculiar order of events, different from the order of events which we encounter in the physical world, but determined by the same kind of forces as those that rule in that world, it is indeed the only theory which is not materialistic.9

8.44. Superficially there may seem to exist a closer connexion between the theory presented here and the so-called ‘double aspect theories’ of the relations between mind and body. To scribe our theory as such, however, would be misleading. What could be regarded as the ‘physical aspect’ of this double-faced entity would not be the individual neural processes but only the complete order of all these processes; but this order, if we knew it in full, would then not be another aspect of what we know as mind but would be mind itself. We cannot directly observe how this order is formed by its physical elements, but can only infer it. But if we could complete the theoretical reconstruction of this order from its elements and then disregard all the properties of the elements which are not relevant to the existence of this order as a whole, we should have a complete description of the order we call mind—just as in describing a machine we can disregard many properties of its parts, such as their colour, and consider only those which are essential to the functioning of the machine as a whole. (Cf. 2.28–2.30.)

8.45. This order which we call mind is thus the order prevailing in a particular part of the physical universe—that part of it which is ourselves. It is an order which we ‘know’ in a way which is different from the manner in which we know the order of the physical universe around us. What we have tried to do here is to show that the same kind of regularities which we have learnt to discover in the world around us are in princple also capable of building up an order like that constituting our mind. That such a kind of sub-order can be formed within that order which we have discovered in the external universe does not yet mean, however, that we must be able to explain how the particular order which constitutes our mind is placed in that more comprehensive order. In order to achieve this it would be necessary to construct, with special reference to the human mind, a detailed reproduction of the model-object relation which it involves such as we have sketched schematically before in order to illustrate the general principle (5.77–5.91).

8.46. While our theory leads us to deny any ultimate dualism of the forces governing the realms of mind and that of the physical world respectively, it forces us at the same time to recognize that for practical purposes we shall always have to adopt a dualistic view. It does this by showing that any explanation of mental phenomena which we can hope ever to attain cannot be sufficient to ‘unify’ all our knowledge, in the sense that we should become able to substitute statements about particular physical events (or classes of physical events) for statements about mental events without thereby changing the meaning of the statement.

8.47. In this specific sense we shall never be able to bridge the gap between physical and mental phenomena; and for practical purposes, including in this the procedure appropriate to the different sciences, we shall permanently have to be content with a dualistic view of the world. This, however, raises a further problem which must be more systematically considered in the remaining sections of this chapter.

4. THE NATURE OF EXPLANATION

8.48. What remains now is to restate briefly what the theory outlined in the preceding pages is meant to explain, and how far it can be expected to account for particular mental processes. This makes it necessary to make more precise than we have yet done what we mean by ‘explanation’. This is a peculiarly relevant question since ‘explanation’ is itself one of the mental processes which the theory intends to explain.

8.49. It has been suggested before (5.44–5.48) that explanation consists in the formation in the brain of a ‘model’ of the complex of events to be explained, a model the parts of which are defined by their position in a more comprehensive structure of relationships which constitutes the semi-permanent framework from which the representations of individual events receive their meaning.

8.50. This notion of the ‘model’, which the brain is assumed to be capable of building, has, of course, been often used in this connexion,10 and by itself it does not get us very far. Indeed, if it is conceived, as is usually the case, as a separate model of the particular phenomenon to be explained, it is not at all clear what is meant by it. The analogy with a mechanical model is not directly applicable. A mechanical model derives its significance from the fact that the properties of its individual parts are assumed to be known and in some respects to correspond to the properties of the parts of the phenomenon which it reproduces. It is from this knowledge of the different properties of the parts that we derive our knowledge of how the particular combination of these parts will function.

8.51. In general, the possibility of forming a model which explains anything presupposes that we have at our disposal distinct elements whose action in different circumstances is known irrespective of the particular model in which we use them. In the case of a mechanical model it is the physical properties of the individual parts which are supposed to be known. In a mathematical ‘model’ the ‘properties’ of the parts are defined by functions which show the values they will assume in different circumstances, and which are capable of being combined into various systems of equations which constitute the models.

8.52. The weakness of the ordinary use of the concept of the model as an account of the process of explanation consists in the fact that this conception presupposes, but does not explain, the existence of the different mental entities from which such a model could be built. It does not explain in what sense or in which manner the parts of the model correspond to the parts of the original, or what are the properties of the elements from which the model is built.

8.53. The concept of a model that is being formed in the brain is helpful only after we have succeeded in accounting for the different properties of the parts from which it is built. Such an account is provided by the explanation of the determination of sensory (and other mental) qualities by their position in the more comprehensive semi-permanent structure of relationships, the ‘map’ of the world which past experience has created in the brain, which has been described in the preceding pages. It is the position of the impulse in the connected network of fibres which brings it about that its occurrence together with other impulses will produce certain further impulses. The formation of the model appears thus merely a particular case of that process of joint or simultaneous classification of a group of impulses of which each has its determined significance apart from the particular combination or model in which it now occurs.

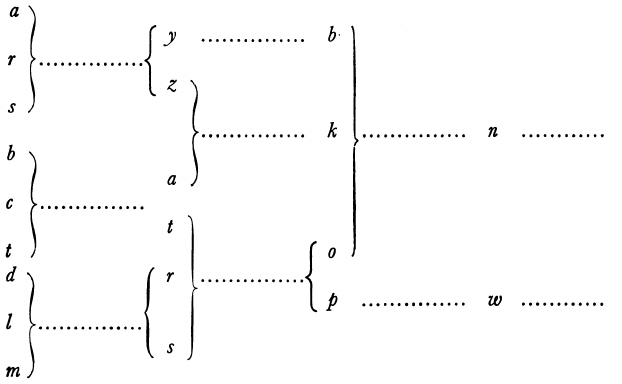

8.54. We can schematically represent this process of joint classification which produces a model in the following manner: the different elements, the mental qualities from which the model is built, are classes of impulses which we may call A, B, C, etc., and which are defined as an a (member of A) producing x (and perhaps some other impulses) when it occurs in company with o, p, . . . , but producing v, z, . . . when it occurs in company with r, s, . . . etc., etc., and similarly for all members of the classes B, C, etc. In this definition any given class of impulses may, of course, occur both in a ‘primary’ character, that is as an element of a class to be defined by the impulses which any element of this class will evoke, and in a ‘secondary’ character as an evoked impulse which determines the class to which some other impulses belong. (3.38, 3.55ff.) Impulses of the class A will appear not only in statements like ‘if (a, o, p) then x‘ and ‘if (a, r, s) then(y, z . . . ), but also in statements like ‘if (b, c, q) then (a, t) etc.

8.55. Given such a determination of the different significance of impulses of the different classes, it follows that any given combination of such impulses will produce impulses standing for other classes, and these in turn others, and so on, somewhat as in the following schematic representation:

8.56. The particular result produced is thus recognized to be the effect of the simultaneous occurrence of certain elements in a particular constellation which, if we had known of their presence, would have enabled us to predict the result. Once we have formed such a model we are in a position to say on which of the various elements in the actual situation the observed result depends, and how it would be modified if any of these elements were changed; this is what an explanation enables us to do.

5. EXPLANATION OF THE PRINCIPLE

8.57. It follows from what has been said so far about explanation that it will always refer to classes of events, and that it will account only for those properties which are common to the elements of the class. Explanation is always generic in the sense that it always refers to features which are common to all phenomena of a certain kind, and it can never explain everything to be observed on a particular set of events.

8.58. But although all explanation must refer to the common features of a class of phenomena, there are evidently different degrees to which an explanation can be general, or to which it may approach to a full explanation of a particular set of events. The model may reproduce only the few common features of a great variety of phenomena, or it may reproduce a much larger number of features common to a smaller number of instances. In general, it will be true that the simpler the model, the wider will be the range of particular phenomena of which it reproduces one aspect, and the more complex the model, the more will its range of application be restricted.11 In this respect the relation of the model to the object is similar to that between the connotation and the denotation (or the ‘intension’ and the ‘extension’) of a concept.

8.59. Most explanations (or theories) with which we are familiar are intended to show a common principle which operates in a large number of particular instances which in other respects may differ widely from each other. We have referred already earlier (2.18–2.19) to such explanations as ‘explanations of the principle’.12 The difference between such ‘explanations of the principle’ and more detailed explanations is, of course, merely one of the degree of their generality, and strictly speaking no explanation can be more than an explanation of the principle. It will be convenient, however, to reserve the name ‘explanation of the principle’ for explanations of a high degree of generality, and to contrast them with explanations of the detail.

8.60. The usual kind of explanation which we give, e.g., of the functioning of a clockwork, will in our sense be merely an explanation of the principle. It will merely show how the kind of phenomena which we call clockworks are produced: the manner in which a pair of hands can be made to revolve at constant speeds, etc. In the same ‘general’ way most of us are familiar with the principles on which a steam engine, an atomic bomb, or certain kinds of simple organisms function, without therefore necessarily being able to give a sufficiently detailed explanation of any one of these objects so that we should be able to construct it or precisely to predict its behaviour. Even where we are able to construct one of these objects, say a clockwork, the knowledge of the principle involved will not be sufficient to predict more than certain general aspects of its operation. We should never be able, for instance, before we have built it, to predict precisely how fast it will move or precisely where its hands will be at a particular moment of time.

8.61. If in general we are not more aware of this distinction between explanations merely of the principle and more detailed explanations, this is because usually there will be no great difficulty about elaborating any explanation of the principle so as to make it approximate to almost any desired degree to the circumstances of a particular situation. By increasing the complexity of the model we can usually obtain a close reproduction of any particular feature in which we are interested.

8.62. The distinction between the explanation of the principle on which a wide class of phenomena operate and the more detailed explanation of particular phenomena is reflected in the familiar distinction between the ‘theoretical’ and the more ‘applied’ parts of the different sciences. ‘Theoretical physics’, ‘theoretical chemistry’ or ‘theoretical biology’ are concerned with the explanation of the principles common to all phenomena which we call physical, chemical or biological.

8.63. Strictly speaking we should, of course, not be entitled to speak at all of phenomena of a certain kind unless we know some common principles which apply to the explanation of the phenomena of that kind. The various ways in which atoms are combined into molecules, e.g., constitute the common principles of all the phenomena which we call chemical. It is quite possible that an observed phenomenon, supposed to be, say, chemical, such as a change in the colour of a certain substance, may on investigation prove to be an event of a different kind, e.g., an optical event, such as a change in the light falling on the substance.

8.64. While it is true that a theoretical class of phenomena can be definitely established only after we have found a common principle of explanation applying to all its members, that is, a model of high degree of generality reproducing the features they all have in common, we will yet often know of a range of phenomena which seem to be similar in some respect and where we therefore expect to find a common principle of explanation without, however, as yet knowing such a principle. The difference between such prima facie or ‘empirical’ classes of phenomena, and the theoretical classes derived from a common principle of explanation, is that the empirical class is limited to phenomena actually observed, while the theoretical class enables us to define the range over which phenomena of the kind in question may vary.

8.65. The class of events which we call ‘mental’ has so far on the whole been an empirical class in this sense. What has been attempted here might be described as a sketch of a ‘theoretical psychology’ in the same sense in which we speak of theoretical physics or theoretical biology. We have attempted an explanation of the principle by which we may account for the peculiarities which are common to all processes which are commonly called mental. The question which arises now is how far in the sphere of mental processes we can hope to develop the explanation of the principle into more detailed explanations, especially into explanations that would enable us to predict the course of particular mental events.

6. THE LIMITS OF EXPLANATION

8.66. It is by no means always and necessarily true that the achievement of an explanation of the principle on which the phenomena of a certain class operate enables us to proceed to explanations of the more concrete detail. There are several fields in which practical difficulties prevent us from thus elaborating known explanations of the principle to the point where they would enable us to predict particular events. This is often the case when the phenomena are very complex, as in meteorology or biology; in these instances, the number of variables which would have to be taken into account is greater than that which can be ascertained or effectively manipulated by the human mind. While we may, e.g., possess full theoretical knowledge of the mechanism by which waves are formed and propagated on the surface of water, we shall probably never be able to predict the shape and movements of the wave that will form on the ocean at a particular place and moment of time.

8.67. Apart from these practical limits to explanation, which we may hope continuously to push further back, there also exists, however, an absolute limit to what the human brain can ever accomplish by way of explanation—a limit which is determined by the nature of the instrument of explanation itself, and which is particularly relevant to any attempt to explain particular mental processes.

8.68. If our account of the process of explanation is correct, it would appear that any apparatus or organism which is to perform such operations must possess certain properties determined by the properties of the events which it is to explain. If explanation involves that kind of joint classification of many elements which we have described as ‘model-building’, the relation between the explaining agent and the explained object must satisfy such formal relations as must exist between any apparatus of classification and the individual objects which it classifies. (Cf. 5.77–5.91.)

8.69. The proposition which we shall attempt to establish is that any apparatus of classification must possess a structure of a higher degree of complexity than is possessed by the objects which it classifies; and that, therefore, the capacity of any explaining agent must be limited to objects with a structure possessing a degree of complexity lower than its own. If this is correct, it means that no explaining agent can ever explain objects of its own kind, or of its own degree of complexity, and, therefore, that the human brain can never fully explain its own operations. This statement possesses, probably, a high degree of prima facie plausibility. It is, however, of such importance and far-reaching consequences, that we must attempt a stricter proof.

8.70. We shall attempt such a demonstration at first for the simple processes of classification of individual elements, and later apply the same reasoning to those processes of joint classification which we have called model-building. Our first task must be to make clear what we mean when we speak of the ‘degree of complexity’ of the objects of classification and of the classifying apparatus. What we require is a measure of this degree of complexity which can be expressed in numerical terms.

8.71. So far as the objects of classification are concerned, it is necessary in the first instance to remember that for our purposes we are not interested in all the properties which a physical object may possess in an objective sense, but only in those ‘properties’ according to which these objects are to be classified. For our purposes the complete classification of the object is its complete definition, containing all that with which we are concerned in respect to it.

8.72. The degree of complexity of the objects of classification may then be measured by the number of different classes under which it is subsumed, or the number of different ‘heads’ under which it is classified. This number expresses the maximum number of points with regard to which the response of the classifying apparatus to this object may differ from its responses to any one other object which it is also capable of classifying. If the object in question is classified under n heads, it can evidently differ from any one other object that is classified by the same apparatus in n different ways.

8.73. In order that the classifying apparatus should be able to respond differently to any two objects which are classified differently under any one of these n heads, this apparatus will clearly have to be capable of distinguishing between a number of classes much larger than n. If any individual object may or may not belong to any one of the n classes A, B, C, . . . N, and if all individual objects differing from each other in their membership of any one of these classes are to be treated as members of separate classes, then the number of different classes of objects to which the classifying apparatus will have to be able to respond differently will, according to a simple theorem of combinatorial analysis, have to be 2n+1.

8.74. The number of different responses (or groups of responses), of which the classifying apparatus is capable, or the number of different classes it is able to form, will thus have to be of a definitely higher order of magnitude than the number of classes to which any individual object of classification can belong. This remains true when many of the individual classes to which a particular object belongs are mutually exclusive or disjunct, so that it can belong only to either A1 or A2 or A3 . . . and to either B1 or B2 or B3 . . . etc. If in such a case the number of variable ‘attributes’ which distinguish elements of A1 from elements of A2 and of A3, and elements of B1 from those of B2 and B3, etc., is m and each of these m different variable attributes may assume n different ‘values’, although any one element will belong to at most m different classes, the number of distinct combinations of attributes to which the classifying apparatus will have to respond will still be equal to nm.

8.75. In the same way in which we have used the number of different classes to which any one element can be assigned as the measure of the degree of its complexity, we can use the number of different classes to which the classifying apparatus will have to respond differently as the measure of complexity of that apparatus. It is evidently this number which indicates the variety of ways in which any one scheme of classification for a given set of elements may differ from any other scheme of classification for the different schemes of classification which can be applied to the given set of elements. Such a scheme for classifying the different possible schemes of classification would in turn have to possess a degree of complexity as much greater than that of any of the latter as their degree of complexity exceeds the complexity of any one of the elements.

8.76. What is true of the relationship between the degree of complexity of the different elements to be classified and that of the apparatus which can perform such classification, is, of course, equally true of that kind of joint or simultaneous classification which we have called ‘model-building’. It differs from the classification of individual elements merely by the fact that the range of possible differences between different constellations of such elements is already of a higher order of magnitude than the range of possible differences between the individual elements, and that in consequence any apparatus capable of building models of all the different possible constellations of such elements must be of an even higher order of complexity.

8.77. An apparatus capable of building within itself models of different constellations of elements must be more complex, in our sense, than any particular constellation of such elements of which it can form a model, because, in addition to showing how any one of these elements will behave in a particular situation, it must be capable also of representing how any one of these elements would behave in any one of a large number of other situations. The ‘new’ result of the particular combination of elements which it is capable of predicting is derived from its capacity of predicting the behaviour of each element under varying conditions.

8.78. The significance of these abstract considerations will become clearer if we consider as illustrations some instances in which this or a similar principle applies. The simplest illustration of the kind is probably provided by a machine designed to sort out certain objects according to some variable property. Such a machine will clearly have to be capable of indicating (or of differentially responding to) a greater number of different properties than any one of the objects to be sorted will possess. If, e.g., it is designed to sort out objects according to their length, any one object can possess only one length, while the machine must be capable of a different response to many different lengths.

8.79. An analogous relationship, which makes it impossible to work out on any calculating machine the (finite) number of distinct operations which can be performed with it, exists between that number and the highest result which the machine can show. If that limit were, e.g., 999,999,999, there will already be 500,000,000 additions of two different figures giving 999,999,999 as a result, 499,999,999 pairs of different figures the addition of which gives 999,999,998 as a result, etc. etc., and therefore a very much larger number of different additions of pairs of figures only than the machine can show. To this would have to be added all additions of more than two figures and all the different instances of the other operations which the machine can perform. The number of distinct calculations it can perform therefore will be clearly of a higher order of magnitude than the highest figure it can enumerate.

8.80. Applying the same general principle to the human brain as an apparatus of classification it would appear to mean that, even though we may understand its modus operandi in general terms, or, in other words, possess an explanation of the principle on which it operates, we shall never, by means of the same brain, be able to arrive at a detailed explanation of its working in particular circumstances, or be able to predict what the results of its operations will be. To achieve this would require a brain of a higher order of complexity, though it might be built on the same general principles. Such a brain might be able to explain what happens in our brain, but it would in turn still be unable fully to explain its own operations, and so on.

8.81. The impossibility of explaining the functioning of the human brain in sufficient detail to enable us to substitute a description in physical terms for a description in terms of mental qualities, applies thus only in so far as the human brain is itself to be used as the instrument of classification. It would not only not apply to a brain built on the same principle but possessing a higher order of complexity, but, paradoxical as this may sound, it also does not exclude the logical possibility that the knowledge of the principle on which the brain operates might enable us to build a machine fully reproducing the action of the brain and capable of predicting how the brain will act in different circumstances.

8.82. Such a machine, designed by the human mind yet capable of ‘explaining’ what the mind is incapable of explaining without its help, is not a self-contradictory conception in the sense in which the idea of the mind directly explaining its own operations involves a contradiction. The achievement of constructing such a machine would not differ in principle from that of constructing a calculating machine which enables us to solve problems which have not been solved before, and the results of whose operations we cannot, strictly speaking, predict beyond saying that they will be in accord with the principles built into the machine. In both instances our knowledge merely of the principle on which the machine operates will enable us to bring about results of which, before the machine produces them, we know only that they will satisfy certain conditions.

8.83. It might appear at first as if this impossibility of a full explanation of mental processes would apply only to the mind as a whole, and not to particular mental processes, a full explanation of which might still enable us to substitute for the description of a particular mental process a fully equivalent statement about a set of physical events. Such a complete explanation of any particular mental process would, if it were possible, of course be something different from, and something more far-reaching than, the kind of partial explanation which we have called ‘explanation of the principle.’

8.84. In order to provide a full explanation of even one particular mental process, such an explanation would have to run entirely in physical terms, and would have to contain no references to any other mental events which were not also at the same time explained in physical terms. Such a possibility is ruled out, however, by the fact, that the mind as an order is a ‘whole’ in the strict sense of the term: the distinct character of mental entities and of their mode of operation is determined by their relations to (or their position in the system of) all other mental entities. No one of them can, therefore, be explained without at the same time explaining all the others, or the whole structure of relationships determining their character.

8.85. So long as we cannot explain the mind as a whole, any attempt to explain particular mental processes must therefore contain references to other mental processes and will thus not achieve a full reduction to a description in physical terms. A full translation of the description of any set of events from the mental to the physical language would thus presuppose knowledge of the complete set of ‘rules of correspondence’13 by which the two languages are related, or a complete account of the orders prevailing in the two worlds.

8.86. This conclusion may be expressed differently by saying that a mental process could be identified with (or ‘reduced to’) a particular physical process only if we were able to show that it occupies in the whole order of mental events a position which is identical with the position which the physical events occupy in the physical order of the organism. The former is a mental process because it occupies a certain position in the whole order of mental process (i.e., because of the manner in which it can affect, and be affected by, other mental processes), and this position in an order can be explained in physical terms only by showing how an equivalent order can be built up from physical elements. Only if we could achieve this could we substitute for our knowledge of mental events a statement of the order existing in a particular part of the physical world.

7. THE DIVISION OF THE SCIENCES AND THE ‘FREEDOM OF THE WILL’

8.87. The conclusion to which our theory leads is thus that to us not only mind as a whole but also all individual mental processes must forever remain phenomena of a special kind which, although produced by the same principles which we know to operate in the physical world, we shall never be able fully to explain in terms of physical laws. Those whom it pleases may express this by saying that in some ultimate sense mental phenomena are ‘nothing but’ physical processes; this, however, does not alter the fact that in discussing mental processes we will never be able to dispense with the use of mental terms, and that we shall have permanently to be content with a practical dualism, a dualism based not on any assertion of an objective difference between the two classes of events, but on the demonstrable limitations of the powers of our own mind fully to comprehend the unitary order to which they belong.

8.88. From the fact that we shall never be able to achieve more than an ‘explanation of the principle’ by which the order of mental events is determined, it also follows that we shall never achieve a complete ‘unification’ of all sciences in the sense that all phenomena of which it treats can be described in physical terms.14 In the study of human action, in particular, our starting point will always have to be our direct knowledge of the different kinds of mental events, which to us must remain irreducible entities.

8.89. The permanent cleavage between our knowledge of the physical world and our knowledge of mental events goes right through what is commonly regarded as the one subject of psychology. Since the theoretical psychology which has been sketched here can never be developed to the point at which it would enable us to substitute for the description of particular mental events descriptions in terms of particular physical events, and since it has therefore nothing to say about particular kinds of mental events, but is confined to describing the kind of physical processes by which the various types of mental processes can be produced, any discussion of mental events which is to get beyond such a mere ‘explanation of the principle’ will have to start from the mental entities which we know from direct experience.

8.90. This does not mean that we may not be able in a different sense to ‘explain’ particular mental events: it merely means that the type of explanation at which we aim in the physical sciences is not applicable to mental events. We can still use our direct (‘introspective’) knowledge of mental events in order to ‘understand,’ and in some measure even to predict, the results to which mental processes will lead in certain conditions. But this introspective psychology, the part of psychology which lies on the other side of the great cleavage which divides it from the physical sciences, will always have to take our direct knowledge of the human mind for its starting point. It will derive its statements about some mental processes from its knowledge about other mental processes, but it will never be able to bridge the gap between the realm of the mental and the realm of the physical.

8.91. Such a verstehende psychology, which starts from our given knowledge of mental processes, will, however, never be able to explain why we must think thus and not otherwise, why we arrive at particular conclusions. Such an explanation would presuppose a knowledge of the physical conditions under which we would arrive at different conclusions. The assertion that we can explain our own knowledge involves also the belief that we can at any one moment of time both act on some knowledge and possess some additional knowledge about how the former is conditioned and determined. The whole idea of the mind explaining itself is a logical contradiction—nonsense in the literal meaning of the word—and a result of the prejudice that we must be able to deal with mental events in the same manner as we deal with physical events.15

8.92. In particular, it would appear that the whole aim of the discipline known under the name of ‘sociology of knowledge’ which aims at explaining why people as a result of particular material circumstances hold particular views at particular moments, is fundamentally misconceived. It aims at precisely that kind of specific explanation of mental phenomena from physical facts which we have tried to show to be impossible. All we can hope to do in this field is to aim at an explanation of the principle such as is attempted by the general theory of knowledge or epistemology.

8.93. It may be noted in passing that these considerations also have some bearing on the age-old controversy about the ‘freedom of the will’. Even though we may know the general principle by which all human action is causally determined by physical processes, this would not mean that to us a particular human action can ever be recognizable as the necessary result of a particular set of physical circumstances. To us human decisions must always appear as the result of the whole of a human personality—that means the whole of a person’s mind—which, as we have seen, we cannot reduce to something else.16

8.94. The recognition of the fact that for our understanding of human action familiar mental entities must always remain the last determinants to which we can penetrate, and that we cannot hope to replace them by physical facts, is, of course, of the greatest importance for all the disciplines which aim at an understanding and interpretation of human action. It means, in particular, that the devices developed by the natural sciences for the special purpose of replacing a description of the world in sensory or phenomenal terms by one in physical terms lose their raison d’être in the study of intelligible human action. This applies particularly to the endeavour to replace all qualitative statements by quantitative expressions or by descriptions which run exclusively in terms of explicit relations.17

8.95. The impossibility of any complete ‘unification’ of all our scientific knowledge into an all-comprehensive physical science has hardly less significance, however, for our understanding of the physical world than it has for our study of the consequences of human action. We have seen how in the physical sciences the aim is to build models of the connexions of the events in the external world by breaking up the classes known to us as sensory qualities and by replacing them by classes explicitly defined by the relations of the events to each other; also how, as this model of the physical world becomes more and more perfect, its application to any particular phenomenon in the sensory world becomes more and more uncertain. (8.17–8.26.)

8.96. A definite co-ordination of the model of the physical world thus constructed with the picture of the phenomenal world which our senses give us would require that we should be able to complete the task of the physical sciences by an operation which is the converse of their characteristic procedure (1.21): we should have to be able to show in what manner the different parts of our model of the physical world will be classified by our mind. In other words, a complete explanation of even the external world as we know it would presuppose a complete explanation of the working of our senses and our mind. If the latter is impossible, we shall also be unable to provide a full explanation of the phenomenal world.

8.97. Such a completion of the task of science, which would place us in a position to explain in detail the manner in which our sensory picture of the external world represents relations existing between the parts of this world, would mean that this reproduction of the world would have to include a reproduction of that reproduction (or a model of the model-object relation) which would have to include a reproduction of that reproduction of that reproduction, and so on ad infinitum. The impossibility of fully explaining any picture which our mind forms of the external world therefore also means that it is impossible ever fully to explain the ‘phenomenal’ external world. The very conception of such a completion of the task of science is a contradiction in terms. The quest of science is, therefore, by its nature a never-ending task in which every step ahead with necessity creates new problems.

8.98. Our conclusion, therefore, must be that to us mind must remain forever a realm of its own which we can know only through directly experiencing it, but which we shall never be able fully to explain or to ‘reduce’ to something else. Even though we may know that mental events of the kind which we experience can be produced by the same forces which operate in the rest of nature, we shall never be able to say which are the particular physical events which ‘correspond’ to a particular mental event.