FIG. 1.—Column at Bedsa. Local style, without capital or base;

FOR the Vedic cult neither permanent buildings nor representations of the gods are necessary. Did an architecture in durable materials, stone or brick, exist from the earliest days of Indian civilization properly so called? It is hardly likely, for no trace of any such architecture has survived, and the caves cut in the rock reveal imitation of wood in almost all their details (Pl. II, B). Save, therefore, for a few copies of foreign architecture, we may take it that all the ancient architecture of India, apart from the caves, was wooden. We know what it was like from about the second century B.C. onwards from the imitations of it in the rock-hewn caves, from the monuments represented in reliefs and paintings, and from the balustrades of the stūpas (Pl. II, A), which we shall discuss presently.

As soon as architecture makes its appearance in India, two distinct currents are seen. Some motives are derived from the local wooden construction, others are imported from the formerly Achæmenian and now Hellenized world. The development of these motives is clear enough. To describe it, I shall make use of the work of Jouveau-Dubreuil, adding several observations of my own.

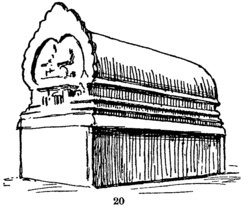

Is the wood construction purely local? It is hard to say. Combaz points out curious likenesses to the wooden architecture of Lycia, but the forms which he mentions seem to result from the very use of wood, and they may well have been invented simultaneously in different regions. Indeed, the long form with the "Gothic" vault (Fig. 20) is found in the huts of the Todas of India to-day.

The most important motive in this wooden architecture, the essential feature of all façades, is the horse-shoe-shaped projection forming a kind of canopy over a door or window (Pl. II, B). It is often, perhaps always, the end of a vault of the same shape, supported by beams, the square ends of which are seen on the front of the building on the inner side of the horse-shoe (Pl. II, B). In time this opening gradually changes; the ends tend to turn in and to become ornate (Pl. III, A). In addition, smaller openings appear beside the main one. On the façades of the caves, from the very beginning (Pl. II, B), one finds false windows of every size under horse-shoe arches. As art develops, these arches become more and more numerous and smaller and smaller. It is an architectural motive which gradually becomes a decorative motive. The false windows, which stood under the horse-shoes in the oldest examples, disappear first of all. Then the arches, supported only by balustrades and stepped cornices, tend to appear in continuous rows. Later, the balustrades and stepped cornices disappear in their turn, and their place is taken by curved cornices along which the arches, now minute, are set in lines, as at Ajanta (Pl. III, A); they are called kuḍu. Then a head appears in these tiny niches, but it does not persist long (sixth to ninth centuries). Later still, fairly large false arches are used to decorate the towers (śikhara) of Northern art. In the Dravidian art of the south they continue to be made small and to be used on cornices under the name of kuḍu. These kuḍus gradually close up completely and are ornamented; then they open out again, so as to give a new effect, which is what we see at the present day. They are also found in the first period of Khmer art (the pre-Angkor art of Cambodia, seventh century), the art of Champa, and the first period of Javanese art.

The horse-shoe arches, as we have seen, are not the only feature of the ancient façades of caves. There were also (Pl. II, B) trapezium-shaped openings, doors or windows (the jambs and columns of the wood construction usually sloping slightly inward), wooden balustrades like those which we shall see round the stūpas, and stepped cornices, generally widening upwards. These cornices, which are likewise imitated from wood, are also found on the top of stūpas, dāgabas (see p. 361 and Pl. III, B), and capitals (Figs. 3, 4). Balustrades and stepped cornices disappear from façades, as I have said, in the sixth century, and instead we have the curved cornice adorned with kuḍus. About the same time,

FIG. 1.—Column at Bedsa. Local style, without capital or base;

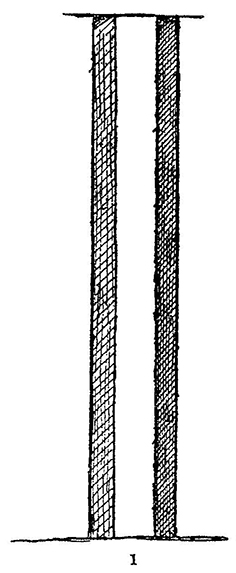

FIG.2.—Column of Asoka. Imported style;

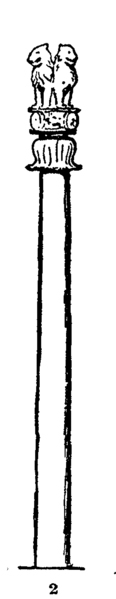

FIG. 3—Column at Karli;

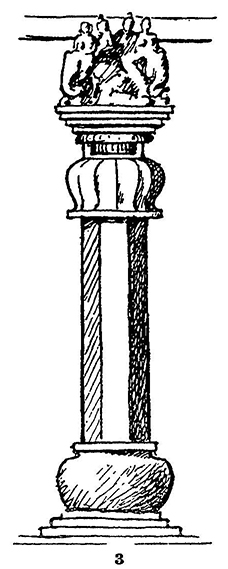

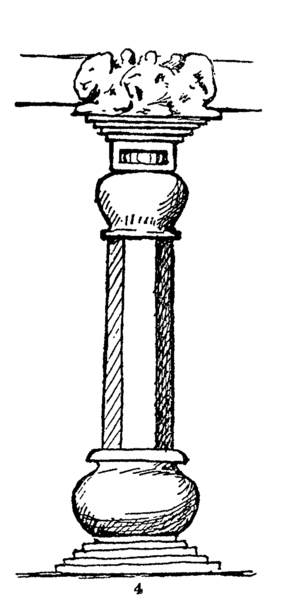

FIG. 4—Column at Nasik.

above the capitals of pillars an elongated slab, with its ends curved on the underside so that they form brackets, takes the place of the stepped form, which only survives on the stūpas and dāgabas.

In wooden architecture the column is a simple eight-sided shaft—a tree-trunk hewn into plane surfaces—without capital or base; so we find it in the oldest caves (Pl. II, B, and Fig. 1). But the Indian column is very early influenced by foreign architecture. The imported form is found in isolated columns—the pillars of Asoka (third century B.C.), which seem to be the most ancient stone monuments or sculptures in India. These mark the holy places of Buddhism. They are very close to Achæmenian art, and except in certain sculptures adorning them have nothing Indian about them. They are round, slender columns, without a base, with a bell-shaped capital surmounted by a fillet and an abacus carved with emblems (Fig. 2, and Pl. VIII, B). The column derived from wood construction and the imported type are very soon amalgamated, and the result is the Indian column with an eight-sided shaft between the imported bell-shaped capital and a base of the same bell-shape inverted, as at Karli (Fig. 3). The fillet presently becomes a sort of cushion, above which is a stepped cornice, itself surmounted by addorsed animals (Fig. 3). This last motive is purely Achæmenian, but it evolves. The human figures riding on animals are often Indian in style and costume. Moreover, the motive is misunderstood; it no longer serves as a support, as at Persepolis, and having nothing above it becomes pure decoration, as at Karli (Figs. 3, 4).

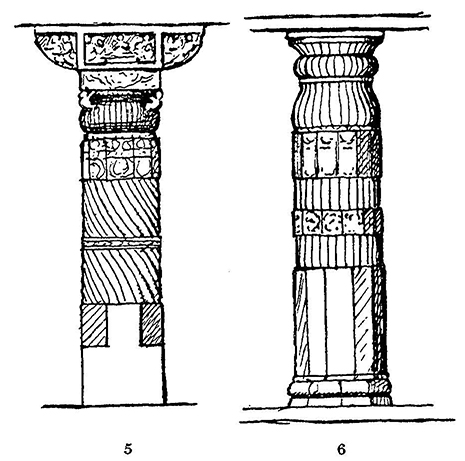

Changes take place in the capital. Its development is like that of the stūpa, the dāgdba (see p. 362), and the summit of the small ornamented pavilion of Dravidian art (paṇchhara). The bell is pinched in at the bottom and so the capital becomes bulbous (Nasik, Fig. 4). As this tendency is exaggerated, the capital takes the form of a turban, usually ribbed. In the classical period (sixth to eighth century) capitals vary very greatly, the most frequent form being the flattened turban with ribbed and rounded sides (Pl. III, A and B; Figs. 5 and 6, etc.). This turban is often set between an upper part which spreads out upwards, possibly a transformation of the old stepped cornice, and a lower part which

FIGS. 5-6.—Column at Ajanta;

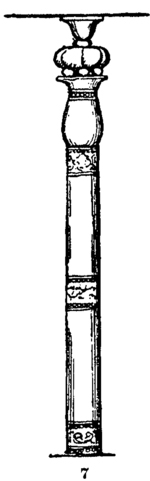

FIG. 7.—Light wooden column, from a painting at Ajanta;

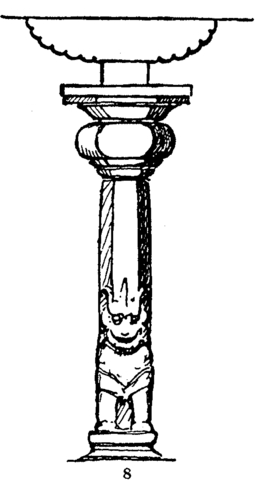

FIG. 8.—Column at Mamallapuram.

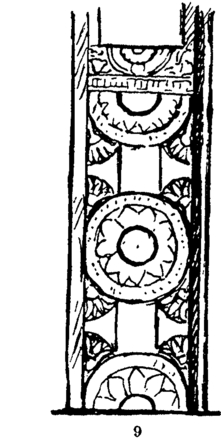

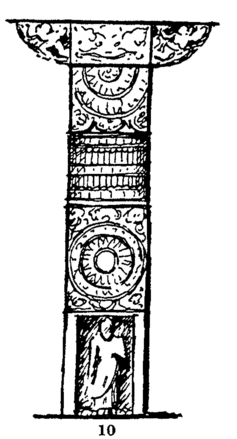

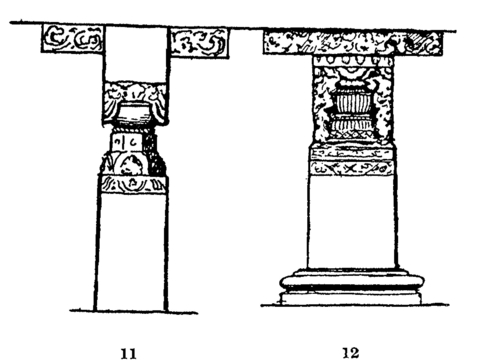

spreads downwards and forms the top of a column (Fig. 6.). Sometimes this last element seems to emerge from a thick square pillar (Fig. 13). In wooden architecture the capital has exactly the same shape, as we see in the frescoes (Fig. 7), but the turban is small and the part below looks like the cup of a flower or a vase. This seems to be the form which one finds again in the eleventh century in Southern India, where it develops, with some complications, down to our own time (Fig. 16). Another capital of the classical age is the basket on the top of a square pillar (Fig. 12). As Jouveau-Dubreuil has shown,1 it seems to be a transformation of the semi-circular relief of half-lotuses with hanging buds which adorned the old piers (Fig. 9), gradually developing (Figs. 10, 11), and being influenced by the turban capital.

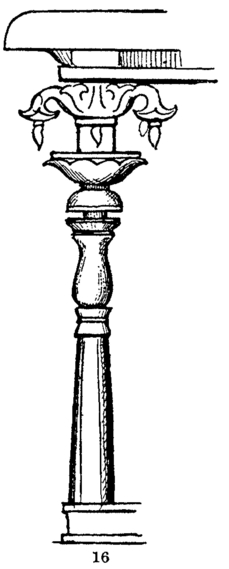

In the classical period the two animals back to back on the top of the column are replaced by long, narrow, bracket-like slabs, curved underneath and often covered with carving (Ajanta and elsewhere, Figs. 5,13-15). This feature, unadorned save for simple semi-circles, we find about the same time in the south, at Mamallapuram, often on a column standing on a lion (Fig. 8). It gradually develops in Dravidian art, at first in the direction of simplicity; then, in the eleventh century, projecting corners spring from the rounded part, and these grow more complicated and turn into floral pendants (Fig. 16). Another type of slab, apparently somewhat later than the other, is found in the classical period, especially at Ellora—a long, flat, rectangular stone (Figs, 11, 12).

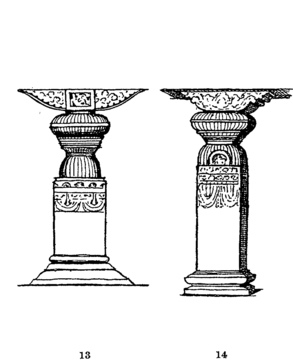

In the classical period there is a great variety of columns. The architects seem in a manner to have played with all the elements which were at their disposal, capitals, round and square columns, and top slabs of every shape, and the strangest combinations are the result. Frequently the column springs from a high base like a pedestal (Fig. 13); frequently, too, a section of round column is set between two square portions; or the whole shaft is square (Fig. 14); and sometimes turban and basket capitals are found one on top of the other, the shaft being supposed to spring from a pillar with a capital of its own (Fig. 15). On the other hand, we find on some facades at Ellora rows of plain square pillars without capital or base, surmounted by flat slabs. This simplicity has its

FIG. 9.—Pilaster at Nasik;

FIG. 10.—Pilaster of a facade at Ajanta;

FIGS. 11-12.—Pillars at Ellora.

character, but it may perhaps only mean that the cave was not completed. Between these plain shafts and combinations of pedestal and column presenting the most complicated form (Fig. 15) and ornament, such as bands and straight or spiral flutings (Figs. 5, 6), one finds every variety of fancy.

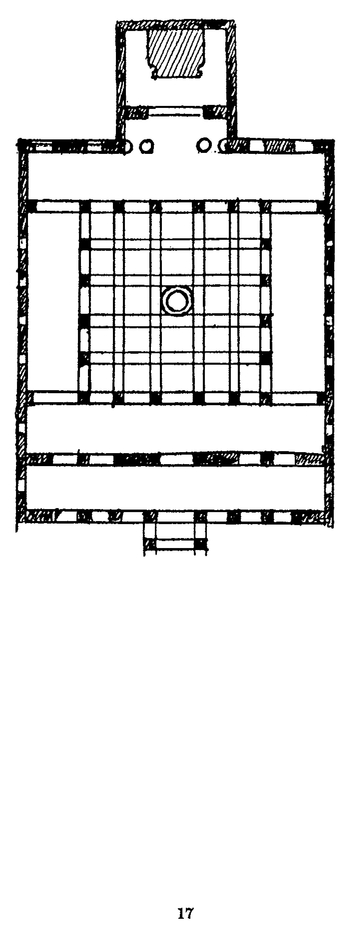

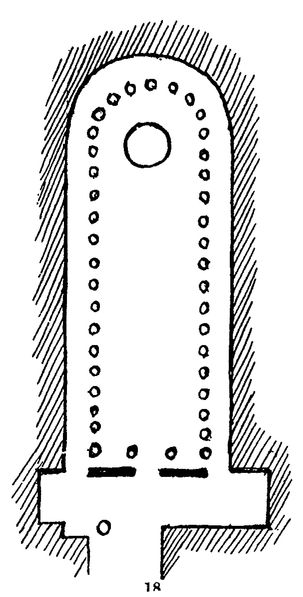

From the earliest caves onwards, there are two distinct plans. One is intended for the dwelling of monks, the other for the hall where men meet to do worship. The former type, in its earliest form, is merely a small apartment cut in the rock, square or oblong, with a flat roof, round which are the cells of the monks. Presently the central hall grows larger, the upper part is supported by columns, and a sanctuary appears at the back and a pillared entrance opposite (Fig. 17). In the other type the plan is long and the upper part, which is high and rounded, seems originally to have been supported by wooden arches, afterwards replaced by stone arches which are exact copies of them (Pl. II, B). The front is adorned by the great horse-shoe arch of which I have spoken. Two rows of columns, which lean inwards in the earliest examples, lead to the apsidal end of the cave in which the dāgaba stands (see p. 361; Fig. 18 ; Pls. II, B, and III, B).

Of the earliest ages of Indian art no monument, other than the caves, survives. Architecture in stone or brick must, therefore, have come in fairly late. With the new architecture the problem of the roof arose. Only very small spaces could be covered horizontally, and the Indians did not know the principle of the vault, in which the stones, cut in trapezium shape, lock together by their weight. The roof was therefore almost always of the corbelled type, in which stones or bricks are laid horizontally one on the other, each projecting a little beyond that below it. But even this method will only cover a small area, and the vault is disproportionately high. The vault may be masked by a wooden ceiling. The problem of roofing explains many peculiarities of Indian architecture, which shows great virtuosity in handling rather primitive technical methods.

In the buildings made of lasting material we find again the two forms which we have seen in the caves, based on wood construction—the square or oblong building, a cella when the walls are low and far apart and a tower when they

FIGS. 13-14.—Pillars at Badami;

FIG. 15.—Pillar at Ellora; Fig.

FIG. 16.—Late Dravidian column.

FIG. 17.—Square plan. Cave 1 at Ajanta;

FIG. 18.—Long plan. Karli.

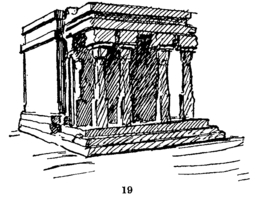

are high and close together, and the long building, which afterwards grows still longer and becomes a gallery. The simplest type of cella is found, with a row of columns on one side, in the small temple at Sanchi (fifth century, Fig. 19),1 and, without a colonnade, in the smallest ratha at Mamallapuram (seventh century), which has a large roof with four curved sides (Pl. IV, A). The long building, with its curved roof terminating at each end in a horse-shoe arch, exists in its most primitive form at Chezarla and Ter (Fig. 20).2

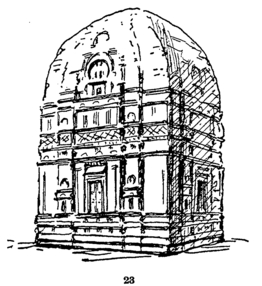

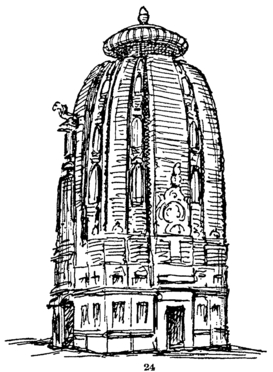

Soon buildings become more complicated. Both types grow larger, and sometimes have a porch in front. At the same time they grow taller, and the cella or tower seems to rise out of the base, which is widened (Pl. IV, B).3 The roof of the cella is developed and made in many stories, adorned with models of square or long buildings in the round, as at Mamallapuram (Pl. IV, A) and Pattakadal.4 The cellae seem to be the product of stone construction, and the towers, with their curved lines, of the use of brick. For brick is easier to work, so making it possible to heighten the building, and the use of flat bricks produces more and more corbellings and stories, which tend to make the lines curved. The tower at first consists of a cella surmounted by a curvilinear portion, as at Sirpur (Fig. 23),5 and is adorned with relief models of buildings, which we also find on the pre-Angkor monuments of the same period in Cambodia. The curvilinear form is gradually accentuated and the decoration marking the many stories is then composed of āmalakas, a sort of ribbed turbans which usually crown the towers. Later, this decoration is formed of small turrets (Fig. 24).

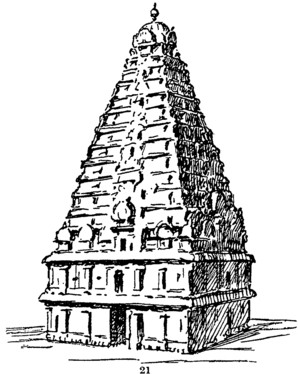

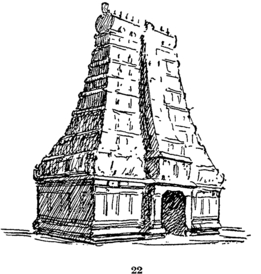

Towers and cellae are combined in certain buildings in the west at the end of the classical period (Pattakadal, Aihole, etc.). Later, the very high cella becomes the essential element of the architecture of Southern India and the curvilinear tower that of the north. In the south, the cella continues to grow in height while the stories of its roof become more numerous; so it eventually becomes the vimāna, the sanctuary of the Dravidian temple, the best-known example of which is at Tanjore (tenth and eleventh centuries, Fig. 21). In time the vimāna is as it were flattened, and becomes the gopura, or gate-house, characteristic of Dravidian monuments from the thirteenth century to the present day (Fig. 22). The curvilinear tower (śikhara) is the principal element of the northern temple from the eighth century to modern times

FIG. 19.—Temple, Sanchi;

FIG. 20.—Temple, Chezarla.

(Fig. 24). Some Jain temples have domed halls. In Mysore there is a peculiar style: the chief part of the temple, which is set on a base, is almost pyramidical, with re-entrant angles in the plan which give it a star shape. This form seems to be intermediate between the northern tower and the southern vimāna.

FIG. 21.—Vimāna, Tanjore;

FIG. 22.—Gopura, Madura.

From the architecture of India in classical times those of Indonesia and Indo-China are derived. In Java, in its first period (eighth to tenth century), the buildings are chiefly cellae standing on a base, with staged roofs and models of buildings or little stūpas at the corners. In Indo-China the Cham art of Annam, the pre-Angkor Khmer art of Cambodia from the end of the sixth century to the ninth, and the art of Dvaravati (in Siam) produce sanctuaries of brick in the form of towers, not unlike the earliest towers of India, such as that at Sirpur. But whereas Cham art continues all through its development to use isolated towers of brick, sometimes accompanied by small oblong buildings, Khmer art evolves quickly, and abandons brick for stone. In this latter architecture, at first towers are arranged in groups and pyramidical temples in stories are erected in imitation of the holy mountain—a conception which perhaps corresponds to that of Borobudur in Java. Presently the two forms are combined and the towers are arranged on the pyramid, at the centre and corners of the monument, as in the eastern Mebun and at Pré Rup and Ta Kèo; then the number of towers on each story is increased and they are connected by galleries. Finally, the temple is enlarged, the galleries are developed (since they often rest on columns on one side only, they can be multiplied and run one into another without any effect of heaviness), the stories are thus connected by cross galleries, and small isolated monuments are added, such as sections of galleries standing on a terrace, until the culmination is reached in the temple of Angkor Wat (first half of the twelfth century), which may be regarded as the most astonishing and the most perfect example of what can be done by an architecture in which the only method of covering a space is by the corbel vault.

In decoration we again come upon the two currents which appear with the first rise of Indian art properly so called—local art and imported art. We shall see them again in the representation of divine, human, and animal forms. The local ornament, of which there are fine examples at Bharhut (second century B.C.), consists chiefly of heavy plants treated in high relief (lotuses and other plants with dangling garlands),

FIG. 23.—Śikhara, Sirpur;

FIG. 24.—Śikhara, Bhuvanesvar.

often accompanied by aquatic creatures, etc. (Pl. V, B). The other type of decoration makes use of a great number of motives from the Hellenized East, which are usually old Achæmenian motives slightly altered (Pl. V, C). Thus we find animals, often fanciful, addorsed or confronted, sometimes having the short curved wings known as "Oriental wings" and sometimes prancing with little riders on their backs. There are griffins, winged horses, lions, centaurs, serpenttailed men, horses prancing in opposite directions in front of a car seen end on, Atlantes, heavy garlands held by human figures, palmettes, etc. (Combaz's list).

The local style of ornament prevails at Bharhut. Later, on the gates of the Great Stupa at Sanchi, the imported style comes into more prominence and the two styles, local and imported, are found side by side on the jambs (Pl. V, B and C).

In the Græco-Buddhist art which reigned in Northwestern India from shortly before our era to about the fifth century, more purely Greek motives are found. The Græco-Roman acanthus capital bearing a small Buddhist figure seated in the Indian manner might be regarded as the symbol of that art, the fusion of two cultures. This capital and other decorative features peculiar to Græco-Buddhist art do not seem to have made their way into the art of India in general. Specifically Græco-Buddhist motives are hardly found again except in Kashmir (eighth to tenth century), which for a short time had an architecture of its own, employing Greek columns and trefoil arches set in gables. On religious art and on representations of the human figure, as we shall see, Græco-Buddhist art had a considerable influence. But in the decorative domain it made little difference, and still less in that of architecture, in which, be it noted, we have had no occasion to mention it at all.

In the classical age the old decorative motives almost all disappear. Decoration is chiefly sculptural. Fagades, pillartops architraves, and piers are covered with human figures and little scenes which take the place of motives borrowed from architecture (Pl. III).

In all ages the amazing imagination of India in the decorative sphere makes up for its ignorance of certain technical processes of architecture.

The stūpa (Pl. II, A) is connected both with architecture and with sacred art, and for that reason we shall study it by itself. It is a fundamentally Indian structure, appearing with Indian art itself and spreading with Buddhism. It consists of a hemispherical mound of masonry set on a base and crowned by a cubical "tee" and an umbrella. In small stūpas the "tee" is surmounted by a stepped cornice.

The origins and the purpose of the stūpa have been very clearly indicated by Foucher. It was originally a funerary monument and tumulus, to hold the ashes of Buddha, which were, it is said, divided into eight parts and laid in eight stūpas. In later times Asoka found seven of these stūpas; the eighth was lost in the jungle, and it was said that the Nagas who guarded the relics which it contained refused to deliver them up to the king. Asoka collected the ashes, divided them, and built a large number of these gigantic reliquaries for them. So the function of the stūpa was extended; it served to protect the ashes of the saints and also, where ashes were lacking, other relics of the Blessed One. Finally, having become the chief form of sacred monument, it was used as a memorial, to mark the scene of a miracle or other great event. So, in districts where the Buddhist faith was lively but Buddha himself had never been in his last existence, stūpas were erected where one or another Jātaka, an event in his previous lives, had occurred.

Stūpas were of all sizes. The large ones (Pl. II, A) were oftensurrounded by balustrades with entrance-gates, doubtless intended to keep out malign influences and to bound the holy ground on which the pradakshiṇā was performed, the rite of going round a being or a symbol, keeping it on one's right hand, to honour it. Sometimes smaller stūpas containing the ashes of monks were grouped round the main edifice. Inside temples and at the inner end of the oblong buildings which served as a place of prayer there were small stūpas called dāgabas (see above, p. 352; Pls. II, B, and III, B). As time went on the stūpa grew higher and changed its shape. In the earliest examples the dome is as it were flattened and the terrace is low (Pl. II, A). By the first century of our era, both terrace and dome are considerably higher. Passing through an evolution similar to that of the capital, the dome assumes a bell shape, the lower part being drawn in, and the base, especially in certain dāgabas, becomes higher than ever (Ajanta, Pl. III, B).

The stūpa vanishes from India with Buddhism, but it continues in use down to modern times in the countries where the Buddhism of the Small Vehicle prevails—Ceylon, Burma, Siam, Cambodia, Laos. There it becomes yet taller and more pointed, and is like the head-dresses of the dancing-girls, having the form of a bell, wide at the bottom and ending in a spike above.

The earliest stūpas and dāgabas are not ornamented with sculpture, but the balustrades surrounding them are covered with medallions and friezes (Bharhut, etc.). Elsewhere, as in the Great Stupa of Sanchi, the balustrades are only a plain imitation of wooden railings, and the reliefs are grouped about the entrances (Pl. II, A). Later the stūpa itself is adorned with scenes and decoration, in rows one above the other, running round the base and possibly in a collar round the dome, as at Amaravati. On the very high bases, covered with carving, of the classical dāgabas at Ajanta, Ellora, and elsewhere, a large Buddha often stands out prominently, generally seated in the European fashion (Pl. III, B).

1 CCCXXVIII, fig. 71.

1 CCCVII, fig. 151.

2 Ibid., fig. 147.

3 Ibid., figs. 148, 158, 188.

4 Ibid., figs. 187-8, 197, 201-2, etc.

5 Ibid., fig. 186.