From Men and Thought in Ancient India, by R. Mookerji. Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1924.

THANKS to the information supplied by the Greeks— Arrian, Diodorus Siculus, Plutarch, Polyænus, Strabo— the expedition of Alexander appears to us as the chief event in the history of ancient India. Our point of view would be different if we were guided by native sources; we should hardly be told of an event which, though so astonishing, was of limited range and affected only part of India.

This expedition was the natural consequence of the establishment of the Macedonian power in Persia; it was as heir to the Great King that Alexander, carrying on the tradition of Cyrus and Darius, entered the Punjab. If the successors of Xerxes had been able to maintain their authority over the satrapies set up on the Indus by the great Achæmenids, the Western conqueror could have reached the land of the Five Rivers without striking a blow. Midway between the Greek and Indian points of view there is a Persian point of view, from which we should judge the events now to be described.

After the capture of Persepolis in 330, Alexander reduced Seistan and the Helmand valley and founded Arachosian Alexandria (Kandahar). In the rigours of the winter of 329-328 he crossed the mountains which lay between him and the valley of the Kabul. He was not yet aiming at India, but at Bactriana, the modern Balkh and Bukhara. To establish his power in that region on the ruins of the Persian sway, he founded military colonies on both sides of the Hindu Kush, which separates the Kabul River (Cophen) from the basin of the Oxus. The year 327 was spent in subduing the hillmen of the Chitral and Swat Rivers, which flow into the Kabul from the north. Alexander founded Nicæa in this semi-Indian country, which he made into a satrapy under Nicanor. When he came to the region of the Indus he had been for over a year in communication with Ambhi, the crown prince of the state which lay on that river.

So the crossing of the Indus on a bridge of boats above the confluence of the Kabul was effected without any opposition, and the army was well received at Takshasila (Taxila), the capital of the state, where Ambhi, on the death of his father, had just become king. Alexander confirmed him in his authority and assured him of his friendship. The first contact of Greeks and Indians was made and organized. Onesicritos the Cynic discussed Pythagoras and Socrates with naked ascetics.

On the other side of the Jhelum (Hydaspes), the westernmost of the five tributaries of the Indus, reigned a rival of Ambhi, belonging to the Puru dynasty. This "Puruid", as a Greek would have called him, or "Paurava", to talk Sanskrit, is the Porus of the Greek historians. He mobilized an army against the invader, but he found himself faced not only by the Macedonians but by native Indians, who were already vassals or allies of Alexander. The conflict which was about to take place can hardly be regarded as a war of Greeks against Indians. Greece Proper was only accidentally involved in the ventures of the King of Macedon, who was here acting as holder of the throne of the Achaemenids. The enemy, on the other hand, was only one of the many rajas of a country which was without any sort of unity, and could not regard himself as the champion of an Indian world inspired by a common patriotism. This Paurava, whose name we do not know, fought simply as the hereditary foe of the Rajah of Takshasila.

His army, according to Arrian, consisted of 30,000 foot, 4,000 horse, 300 chariots, and 200 elephants. At the beginning of 326 it concentrated on the Jhelum to prevent a crossing. The spring went by, while Alexander methodically prepared his advance, diverting the enemy's attention by various feints. When the day came, the Macedonian must indeed have seemed to come down like a thunderbolt, for a body of his troops suddenly crossed the river, at some distance from the main army, in a violent storm. The elephants, on which the Paurava had counted to create alarm among the enemy, were turned by the cavalry, 11,000 in number, led by Alexander himself. This cavalry, with the aid of archers from Central Asia, decided the battle; the infantry stepped in when the Indians were already thrown into utter confusion. Of the Indians 12,000 were cut down and 9,000 taken prisoner. Wounded nine times before he was captured, the Paurava claimed the treatment due to a king, and indeed Alexander restored him to his throne, but under his own overlordship.

Between the Jhelum and the next affluent of the Indus to the east, the Chenab (Acesines), lay the people of the Glausæ or Glauganicæ, who soon submitted. The army, proceeding along the spurs of the Himalaya, had reached the next river, the Ravi (Hydraotes), through the country of the Adhrishtas (Adræstæ) and a people whom Arrian calls the Cathæi. This last name stands for the ICshatriyas, who were, as we shall see, the noble, warrior caste in every Hindu society, not a particular nation. If it was recorded by the Greek historians, it was doubtless because a people in that district was ruled by a military aristocracy. Their capital, Sangala, was placed in a state of defence. This city, a traditional enemy of the Paurava king, was attacked by Alexander and his Indian ally, the latter of whom vented his destructive rage on such ruins as the Macedonian troops left. With more caution the Raja Saubhuti, whom the Greeks describe under the name of Sophytes as a remarkable administrator, received Alexander with gifts and honours.

At the fourth river beyond the Indus, the Beas (Hyphasis), the Greek advance was to come to a final halt. The commander's authority was faced by an obstinate determination on the part of his lieutenants that the conquest should be pursued no further. He shut himself up for three days in his tent and then decided to retire. But before giving the order he sacrificed to the gods of Hellas and erected twelve monumental altars on the west bank of the river. All that was lacking to the conquest was the last stage, the country leading to the Sutlej, the easternmost affluent of the Indus. For Alexander seems to have had no intention of attacking the states of the Ganges basin, about which he probably had no definite information.

The return commenced at the end of July, 326, across the states of the Paurava, now extended to the Beas. West of the Jhelum Alexander allowed three kingdoms to remain as his vassals—that of Ambhi between the Jhelum and the Indus and those of the Rajas of Abhisara and Urasa (Arsaces) in the upper valley of the river, in Kashmir. He ordered the Cretan Nearchos to get ready a fleet which, with Egyptian, Phœnician, and Cypriot crews, should descend the Jhelum and Indus to the sea. This last phase of the expedition, which was very hard, completed the conquest at the same time as it commenced the retreat. It was an achievement without parallel in the history of any country, the march of exhausted troops down an unknown river under a blazing sun between two deserts. On the two banks the divisions of Hephæstion and Crateros escorted the slowly-moving armada, fighting as they went. More than once the situation was saved by the action of the leader himself with his tactical genius.

As the army proceeded down the Indus it passed the mouths of the various tributaries, the upper waters of which it had recently conquered. It had started this part of its journey in November, 326. Ten days later it came to the Chenab. The troops marched through the country of the Sibæ, and then came, between the Chenab and Ravi, to the Malavas (Malli), who brought out a force of 100,000 fighting men. By quick manœuvring the Greeks extricated themselves from a nasty situation and slaughtered their opponents wholesale. Those of the Malavas who survived and the more prudent Kshudrakas (Oxydracæ), who lived between the Ravi and Sutlej, heaped Alexander with gifts—cotton goods, ingots of steel, and tortoiseshell. These wealthy tribes were annexed to the satrapy of Philip, which extended north-west of the Indus to the Hindu Kush (Paropanisadæ).

The first half of 325 was occupied in the descent of the Indus to Pattala, near Bahmanabad, where the delta began at that period. On the way Alexander had reduced "Musicanus", the chief of the Mushikas, to subjection without fighting; but the insurmountable hostility with which he met in these parts was inspired not by the warrior caste but by the Brahman priesthood, those strange "philosophers" who would not submit. The army was split into several bodies. One, led by Crateros, climbed on to the Iranian plateau and took the Kandahar road for Seistan. The fleet left the river and sailed westwards across the ocean under Nearchos. Alexander founded various marine establishments at the mouths of the Indus, which were further north then than now, installed Apollophanes as Satrap of Gedrosia (west of modern Karachi), and then started across Persia for Mesopotamia. He reached Susa in 324, but died in Babylon in June, 323.

The importance of this Indian campaign of Alexander has been both exaggerated and under-estimated. It is true that it had no decisive influence on the destinies of India, for its results were short-lived. Yet the eight years of the Macedonian occupation opened an era of several centuries during which Hellenism was to be a factor not only of civilization but of government on the western confines of the Indian world. Direct contact was established between the Mediterranean civilizations and those of the Punjab and of Central Asia; Semitic Babylonia and the Persian Empire were no longer a screen between West and East. These are facts of immense consequence, not only to Greek or Indian history but to the history of the world, which is the only real history.

In our eyes, India after Alexander is different from India before Alexander in many respects. Thanks to the Greek historians and to coins, there is less bewildering uncertainty about dates. The facts themselves become simple, as if, following the example of the huge Persian or Macedonian Empire, India itself sought to become united.

Magadha, as we have seen, extended its rule more and more over the Gangetic countries during the fourth century. About 322, roughly a year after Alexander's death, that state saw the beginning of a reign of twenty-four years, in which the first Indian empire was founded. A literary work of the fifth or seventh century after Christ, the drama entitled Mudrā-rākshasa, throws some light, though of an uncertain kind, on the palace revolution which set up the Mauryas in the place of the Nandas. Chandragupta, the

usurper, was possibly the natural son of the last Nanda. He was supported by his former teacher, the man who has the name of being the chief political theorist of India, Chanakya or Vishnugupta, who is traditionally identified with Kautilya, the supposed author of the famous Arthaśāstra. The association of Brahmanic influence with material power, one rarely realized, was to be fruitful.

About the time when he was assuming the power at Pataliputra, Chandragupta, supported by the northern states, intervened in the Punjab and exterminated the Macedonian garrisons. For the first time, it seems, the old Indo-European communities of the Indus, which were fundamentally Brahmanic, met with a reaction on the part of the later communities, which had settled in the Ganges basin, where Brahmanism had to come to terms with many rival religions. Attempts at unification in India are so rare through the ages that one must draw attention to the special characteristics of each. The present attempt was definite and forceful. The proof is that Chandragupta appeared as sole lord in the Punjab and Sind when he was faced with a new conqueror from the West, Seleucos Nicator.

In his struggle with Antigonos, Seleucos had in 312 established his supremacy over all Western Asia, with Babylon as capital. Reviving the ambitions of Persia, as Alexander had done, he was obliged to try to recover the satrapies beyond the Indus. Not only did he fail in this, but he gave up Paropanisadæ (Kabul), Aria (Herat), Arachosia (Kandahar), and Gedrosia to Chandragupta, who thus obtained possession of eastern Iran. We do not know the circumstances in which the two powers came into conflict about 302. Apparently Seleucos made his concessions to Chandragupta fairly easily in order to have his hands free in the west and to be able to bring into the line a corps of elephants, as he did at Ipsus in 301. Chandragupta married a daughter of Seleucos and gave an honourable reception to his ambassador Megasthenes, to whom we owe one of the most trustworthy accounts of ancient India, which has unfortunately come down in a very incomplete state.

Chandragupta's dominions extended from Afghanistan to Bengal. They embraced the whole of the north of India, including Kathiawar, to the Narbada, and country to the west outside India itself. This empire was not merely composed of a number of unrelated districts brought together under a single sceptre; it was a real unit, based on a common government which everywhere established not only the King's authority but the public good.

We lack information about the end of the reign of a sovereign who died when he was barely fifty (298). According to the Jain story, which makes him a member of that sect, he abdicated and went away to the south with Bhadrabahu1 during a twelve years' famine, and committed suicide by starvation, an act honoured by that religion. Perhaps there is no truth in this tradition beyond the favour with which Chandragupta treated Jainism and his abdication in favour of his son Bindusara.

Bindusara appears to have advanced the southern boundaries of the Empire a considerable way into the Deccan. Ill a reign of twenty-eight years he strengthened the bonds which united it, and, far from in any way undoing his father's work, he built up an inheritance of power and wisdom for his son, Asoka Priyadarsin. He had dealings with Antiochos Soter and at his court there were permanent ambassadors of that king and perhaps also, towards the end of his reign, of Ptolemy Philadelphos, King of Egypt. Although the Greeks no longer held any Indian territory, they had many opportunities of entering the interior of the country as diplomatists or merchants.

The third king of the Maurya line was not only the greatest native ruler of India, but one of the great philosopher-kings of history. He had the nobility and gentleness of Marcus Aurelius, with no share of his weakness and disillusionment. He had that complete mastery of the spiritual and the temporal which is in theory an attribute of the Chinese kiun tseu, but without the hieratic inertia of non-action. No one has combined energy and benevolence, justice and charity, as he did. He was the living embodiment of his own time, and he comes before us as quite a modern figure. In the course of a long reign he achieved what seems to us to be a mere aspiration of the visionary: enjoying the greatest possible material power, he organized peace. Far beyond his own vast dominions he realized what has been the dream of some religions—universal order, an order embracing mankind.

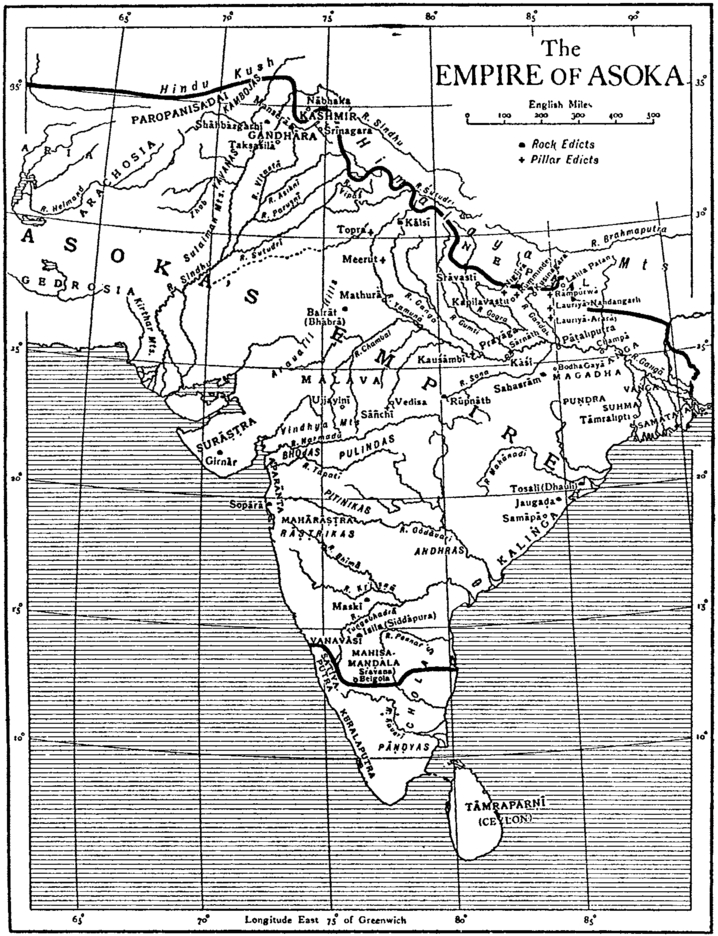

Nor is this unique figure by any means legendary. Though it is wrapped in romantic and untrustworthy stories, the essentials, by a piece of good fortune unusual in history, are provided by epigraphic evidence whose genuineness is beyond dispute. At the four corners of India, rocks or stone pillars engraved with Prakrit inscriptions bear for all time the messages which the sovereign issued to his subjects, messages which tell an objective story without empty vain-glory, giving the rarest of biographies without emphasis.

The manner of thus addressing the people and posterity was inspired by the example of Darius. The architecture and decoration of the monuments which bear these inscriptions confirm the impression, for they definitely recall the style of Persepolis; one has only to look at the capital from Sarnath, now in the Lucknow Museum. The idea of a worldwide kingship in India was taken from the Persian Empire, Like the Achæmenids, Asoka took a passionate interest in the prosperity of his peoples. He founded Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir, and built five monasteries there. In Nepal he built Deo-Patan. In his capital, Pataliputra, he set up palaces of stone in the place of wooden buildings. He completed the irrigation-works started by Chandragupta. He established hospitals everywhere, provided with medical and pharmaceutical resources for man and beast. We must not regard all this as over-sensitiveness or exaggeration of religious scruple on the part of a sickly prince. His fight against suffering of all kinds bears the stamp of Buddhism and Jainism, but the determination to establish a universal order, regulated in its smallest details, for the safeguarding of all interests for which the King assumes the responsibility is the purpose of a "King of Kings".

All interests, moral or material, are regarded with the same width of view and in the same detail. Just as a wide-awake government provides for the policing, financial affairs, and general economics of the country, so there are officials to enforce the reign of the moral law as well as of the purely legal. Tolerance, very different from what we conceive under the name, that is to say, allowing sects to worship as they wish provided that they do not injure internal peace, consists in active zeal on behalf of every religion. For each religion, like the royal power, is defined by the promotion of dharma, which is moral, religious, and civil law all in one. Even if this Law is the tradition of a particular sect or school, it does not menace the safety of the state if the state controls it; and legislation, even if it comes from the King, is not regarded as "secular", as we should say, or extra-religious, for the spiritual power and the temporal, which are divided between two castes, Brahmans and Kshatriyas, are not distinguished in the office of the sovereign. It was not, therefore, out of superstition, nor yet for the sake of syncretism, that Asoka, himself a convert to Buddhism, heaped favours on the Brahmans and gave such help to the Jains that he came to be regarded as one of them. Toleration here is not a makeshift intended to maintain peace, but "the very essence of religion". "To foster one's sect, depreciating the others out of affection for one's own, to exalt its merit, is to do the worst harm to one's own sect." Asoka agrees with "ascetics and Brahmans" in prescribing "mastery of the senses, purity of thought, gratitude, and steadfastness in devotion" (Rock Edict VII), and "the least possible impiety, as many good deeds as possible, kindness, liberality, truthfulness, and purity of deed and thought" (Rock Edict II).

So, when he preaches, with his royal authority, what is ordered by the various religions in common, the King is doing the same organizing work as when he provides for the well-being of his peoples. This policy is expressed in the formula, "Dharma aims at the happiness of all creatures." This noble and simple rule, which is more susceptible of universal application than the Brahman tradition, is preached by Asoka throughout his immense empire as a medium of civilization which can be assimilated by dissimilar races, and he also makes it an instrument of union between the peoples beyond his frontiers. That was how he could become a Buddhist monk without his adhesion to the faith of Sakyamuni entailing any abjuration of Brahmanic orthodoxy; at the very most he repudiated blood-sacrifice, following the precedent of Iranian Zoroaster. His attitude is that of a Great King in whose imperialism no distinction is admitted between spiritual and temporal.

The events of his reign show little sign of these magnificent principles of justice and humanity, at least after a certain date. Having ascended the throne at the age of about 21, about 273, Asoka became a Buddhist nine years later, but his conversion did not take full effect until after a war against the Kalinga country in 261. The war brought victory but great human suffering, for 150,000 were taken prisoners and 100,000 slain. The distress which the King felt over it determined the subsequent turn of his mind. Rock Edict XIII confesses his remorse and proclaims that he has finally taken refuge in the law of Buddha, and in the interests of Buddhism he summoned a council at Pataliputra, the Third Council of tradition, about 240. From then onwards the King strove for no victory but that of the Law, dharma-vijaya, and regarded all men as his children. By the missions which he sent out, he spread the renown of dharma as far as the courts of Antiochos, the grandson of Seleucos Nicator, of Ptolemy Philadelphos in Egypt, of Magas of Cyrene, of Alexander of Epeiros. Other missionaries reached the Tamil kingdoms of the Cholas and the Pandyas, and others established a connexion with Suvarnabhumi (i.e. Lower Burma). Under the conduct of Mahendra, a younger brother of the King, a form of Buddhism was planted in Ceylon (Lanka), where it endured; King Tissa and his successors were to make Anuradhapura one of the great centres of that religion.

The death of the sovereign "dear to the Gods" occurred about 232—at Taxila, according to a Tibetan tradition. At once the Empire was divided between two of his grandsons, Dasaratha obtaining the eastern provinces and Samprati the western.

1 See below, p. 147.