From Men and Thought in Ancient India, by R, Mookerji. Macmillan, 1924.

THE events of the third century are unknown to history, and we have very little information about the Kushan Empire. Daylight only returns in 318-19 when there arises in the old country of Magadha a new dynasty, this time really Indian, which revives the traditions of the Mauryas.

The very name of the founder of this line is a link with the past; another Chandragupta takes the throne of Maghada. His ambition was furthered by a marriage, the memory of which was to be perpetuated by the coins of the period; he married a princess of the house of the Lichchhavis, whom we have already met in the political surroundings of early Buddhism, Thereby Chandragupta I, the first of what historians call the Gupta dynasty, acquired not only Vaisali, but the ancient capital Pataliputra, and he even took in Oudh and Prayaga (Allahabad).

Samudragupta, his son (? 330-380), is an altogether outstanding figure; in the gallery of Indian sovereigns he is the irresistible yet generous conqueror. We have a list of his great deeds in an inscription engraved on one of the pillars which Asoka had set up—that at Allahabad. It seems that somebody—doubtless his successor—wished to place the magnanimous warrior on the level of the peaceful emperor of glorious memory.

Samudragupta's conquests are described according to a conventional scheme by which they are directed towards the various cardinal points (digvijaya). First, there was a great expedition over the Deccan, passing first through the Kalinga country, in accordance with the tradition of Asoka, then following the east coast to Kañchi (Conjeeveram), cutting across to the west coast, and going north along it to the Chandragiri River, and returning by the inland side of the Western Ghats. The memory of this expedition lived long in the south. It was not quite a conquest, for the power of Samudragupta was hardly effective south of the latitude of the sources of the Narbada; yet it was more than a military promenade,1 for in some parts the balance of the Deccan was upset by it. The fall of several thrones, even for a time only, must have furthered the ambitions of a southern dynasty which had a great future before it, the Pallavas, who were already masters of Kanchi when Samudragupta came there. The latter was content to pass through the country as the great overlord and to raise tribute among these distant peoples; he assumed the position of a "King of Kings" and, being unable to absorb such vast regions into his empire, he allowed himself the magnificent gesture of restoring the princes, once he had defeated them, under his own suzerainty.

The warlike ardour of Samudragupta was displayed in three other directions. He exterminated the immediate neighbours of his empire, particularly Ganapati Naga, King of Padmavati (Narwar in Gwalior), and rajas ruling between the Jumna and the Narbada. He reduced the Kings of the Jungle (Central India, according to Fleet) to bondage. He laid tribute on the frontier peoples east and west, from Assam to the republics of the Malavas, Arjunayanas, Yaudheyas, etc.—in other words, to the Punjab. To put the matter briefly, reducing the bombastic language of the inscription to positive statements, we may say that the true domain of Samudragupta embraced the whole of the Ganges basin but not more, and that in the Deccan and in the rest of India his overlordship was not asserted except when it was maintained by effective proof of his strength.

The Sakas of the north-west, with the Murunda portion of their kingdom, and the people of Ceylon are mentioned as distant satellites revolving round the glorious sun. In confirmation, we are informed by a Chinese source that two monks sent by Meghavarrnan of Ceylon (352-379) on a pilgrimage to Buddh Gaya concluded an agreement with the Emperor, by which the Cingalese were allowed to build a monastery in that holy place.

To proclaim and at the same time to consecrate his universal empire, Samudragupta had on his return from the Deccan performed the sacrifice of the horse, an old rite which none had dared to revive since Pushyamitra, the Sunga monarch. Geographically, Samudragupta may not have been the universal overlord, but he was so in the human sense. His magnificence was displayed not only in worldly glory but in liberality to all forms of worship. Although a follower of Vishnu, he was the patron of famous Buddhists, notably Vasubandhu. He had a talent for music and poetry; he appears on coins playing the vīṇā, and was hailed "King of Poets", kavirāja. The inscription describes him as "full of compassion and showing a tender heart ... a true incarnation of goodness ".

A happy era had certainly opened for India and the Indian spirit. The times had now come in which art, literature, Buddhist philosophy, and also orthodox speculation reached their height. Kalidasa was almost contemporary with Asanga. This expansion of culture could not fail to be encouraged by the exceptional succession of a number of remarkable monarchs, all on the whole wise and strong.

Indeed, the son of Samudragupta, Chandragupta II, is the ideal Kshatriya according to the Bhagavadgītā, reconciling, as he did, Vishnuite piety with a passion for war. He conquered the country of the Malavas (Malwa), Gujarat, and Surashtra (Kathiawar), overthrowing the twenty-first "Great Satrap" of the Saka dynasty of Ujjain. As a consequence of this very great extension westwards, he felt it necessary to move the axis of his empire in that direction, and made Ayodhya and Kausambi his capitals instead of Pataliputra. Then, adopting the traditions of Ujjain, where years were reckoned by the era of Vikrama (58 B.C. onwards), he took the title of Vikramaditya, "Sun of Power." It was in his reign (? 375-413) that the famous Chinese pilgrim, Fa-hien, in the course of his fifteen years of travel (399-414) spent several years visiting northern India from Taxila to the Bengalese port of Tamralipti, whence he proceeded to Ceylon and Java. His account brings up before our eyes the prosperity of the cities of the Ganges at the beginning of the fifth century.

Kurnaragupta (413-455), the son of the preceding king, must likewise have sought military glory, since he celebrated the horse-sacrifice. The son whom he left when he died, Skandagupta, is the last great figure of the line (455-480). It was not extinct yet, but henceforth it would rule only a shrunken, mutilated kingdom.

Since the foundation of the Indo-Scythian Empire and the Indianization of the Kushans, for three centuries and a half, India had lived free from foreign invasion. That does not mean that it had been shut off from other peoples; on the contrary, relations with the West and the Far East were more frequent than ever before, but they were peaceful, and so far from hampering the Hindu genius they stimulated it. These favouring circumstances, combined with the creation of large empires, well-policed and strong, that of the Kushans and that of the Guptas, had raised all the potential qualities of native civilization to their height. For in that culture the development of one factor never entails the annihilation of a rival factor. So, although the dynasty of Kanishka had Zoroastrian convictions, it encouraged Buddhism; although the Guptas fostered a brilliant revival of Brahmanic speculation, they assisted a great Buddhist expansion. Letters, arts, and general prosperity benefited likewise; it was the Golden Age of India.

In the last years of Kumaragupta new Iranian peoples assailed the Empire, but they were kept back from the frontiers. Under Skandagupta the first wave of a formidable migration came down upon the same frontiers. This consisted of nomad Mongoloids, to whom India afterwards gave the generic name of Hūṇa, under which we recognize the Huns who invaded Europe. Those who reached India after the middle of the fifth century were the White Huns or Ephtha-lites, who in type were closer to the Turks than to the hideous followers of Attila. After a halt in the valley of the Oxus they took possession of Persia and Kabul. Skandagupta had driven them off for a few years (455), but after they had slain Firoz the Sassanid in 484 no Indian state could stop them. One of them, named Toramana, established himself among the Malavas in 500, and his son Mihiragula set up his capital at Sakala (Sialkot) in the Punjab. Once again Iran and Hindustan were governed by one power.

There was a temporary retreat of the invaders, with a revival of Malava independence, in 528. A native prince, Yasodharman, shook off the yoke of Mihiragula, who threw himself upon Kashmir. We should not fail to note, in this connexion, the increasing importance in the Indian world of the region intermediate between Hindustan and the Deccan, which extends from the Jumna to the Vindhyas and from Avanti to Kathiawar. Already in the fifth century Ujjain had been distinguished by quite especial brilliance, and had been coveted by the Andhras and seized from the Satraps by the Guptas. In the seventh century, in consequence of the weakening of Magadha, where the Gupta line was dying out, we find Malwa becoming the bastion of Hindu resistance. In the Kathiawar peninsula, at Valabhi, the probably Iranian dynasty of the Maitrakas founded at the end of the fifth century a kingdom which was to enjoy great prosperity and brilliant renown as a centre of Buddhism. Between these two centres, Ujjain and Valabhi, a tribe of Gurjaras, related to the Huns, squeezed itself in and settled at Bharukachchha (Broach) and at Bhinmal in southern Rajputana. From this last place, in the middle of the sixth century, one Pulakesin, of the Chalukya clan, emigrated, to establish himself at Vatapi (Badami in the district of Bijapur, Bombay Presidency); this was the beginning of a power which in the seventh century came to rule the Deccan.

The north-west of India had suffered severely. The last of the Kushans, driven out of Bactriana by the Huns and confined to Gandhara in the reign of Kidara, were compelled to leave Gandhara about 475 and to shut themselves up in Gilgit, in the hope that the hurricane would blow over. The Huns did indeed retreat in the middle of the sixth century, and the Kushans recovered part of Gandhara, which they kept until the ninth century. But frightful destruction had been done in the country. Many monasteries were in ruins, and the Graeco-Indian tradition of sculpture was destroyed for ever.

Moreover, the expulsion of the Huns was not equally complete everywhere. A great many remained in the basin of the Indus. What is more, the damage done by the invasion outlasted the invasion itself. The country remained divided up into a confused multitude of states of medium or very small size. Vincent Smith rightly laid stress on the fact that the invasion of the Huns had put an end to a great number of political and other traditions, so that now, in the sixth century, India, where almost everything is traditional in character, found itself at an unusual and critical turning point in its development. We should add that the menace of new barbarian irruptions did not cease to weigh on it; shortly after the middle of the same century the kingdom of the Huns on the Oxus was absorbed into an equally warlike Turkish empire, which continued to be a danger to India until, a hundred years later, in 661, it in its turn fell before the armies of China.

At the beginning of the seventh century a power arose from the chaos in the small principality of Sthanvisvara (Thanesar, near Delhi). Here a courageous raja, Prabhakara-vardhana, learned the art of war in battles with the Huns and created a strong, organized kingdom, which showed its mettle against the Gurjaras, the Malavas, and other neighbouring peoples. Shortly after his death, in 604 or 605, his eldest son, Rajya-vardhana was murdered by the orders of the King of Gauda in Bengal. The power fell to a younger brother, aged sixteen or seventeen, in 606. This young man, Harsha or Siladitya, "Sun of Virtue," made a heroic beginning to a career which was to raise him to the level of Asoka. His life is known to us from the Harsha-charita of Bana and by another contemporary testimony, that of the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang.

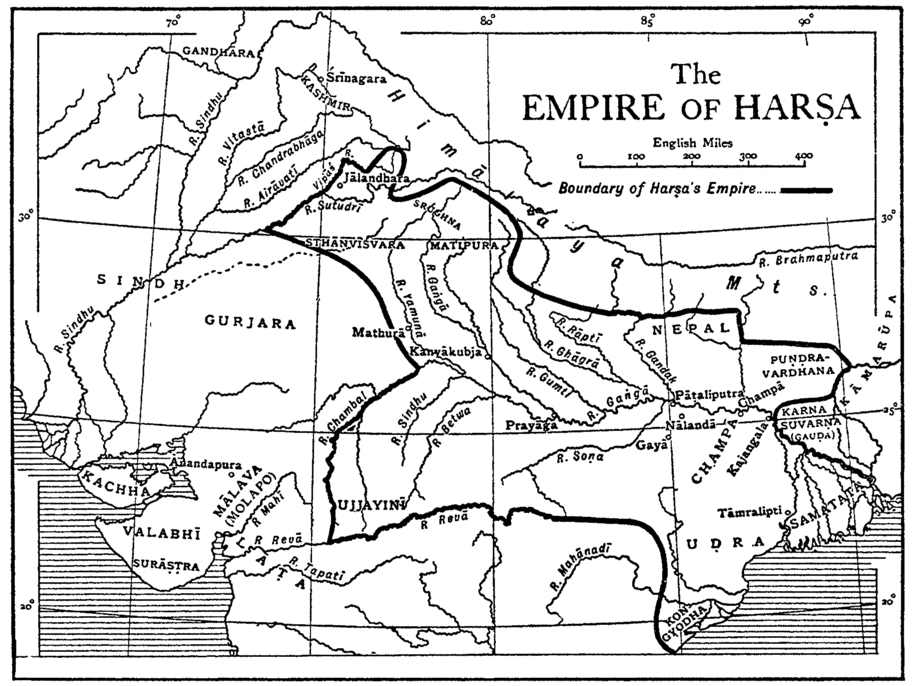

As soon as he was elected by the Council of State, the King chastised the Bengali potentate in a lightning campaign. But then his own brother-in-law, the King of Kanyakubja (Kanauj), was killed by the King of the Malavas. Harsha seized Kanyakubja and made it his capital. So, supporting force with justice and justice with force, he gradually extended his dominions until they reached from the eastern border of the Punjab (exclusive) to the delta of the Ganges. Like Samudragupta, he held Malwa, Gujarat, and Kathiawar, and had the Narbada for his southern frontier. In addition he ruled Nepal. Influenced perhaps by the Gupta conqueror's example, he dreamed of striking a great blow in the Deccan against Maharashtra. In 620 he attacked the king of that country, Pulakesin II, of the Chalukya family, but obtained no great success in this quarter.

Harsha was more than a glorious warrior. He, too, was a kavirāja. He is credited with a grammatical work, poems, and three dramas, Ratnāvalī, Priyadarśikā. and Nāgānanda. With his Sivaite origins he readily reconciled a sincere and touching zeal for Buddhism, the charitable principles of which he made his own. He spent his time in inspecting his provinces, being severe in the suppression of crime but eager to open hospitals and to save all living things from suffering. He received Hiuen Tsang with the greatest honour and for his benefit called a council in his capital (Kanauj, 643) to promote the Mahāyāna. This gathering nearly ended tragically, for the Brahmans had set a conspiracy afoot, either against the Chinese pilgrim or against the King. Nevertheless the King summoned another council immediately afterwards at Prayaga, where he heaped presents upon Brahmans, Jains, and Buddhists alike, Lastly, the literary and artistic brilliance of this age, the first half of the seventh century, falls in no way short of the glory of the Gupta period.

Harsha reigned forty-one years, but died in his full vigour in 647, leaving no heir. In the meantime a Chinese envoy, Wang-hiuen-t'se, came to the court (648), but was ill-treated and robbed by the minister who had seized the throne. He made his escape, and found a refuge and an avenger in Srong-tsan-Gampo, the founder of the Tibetan monarchy. The Nepalese and Tibetans inflicted a defeat on the Indian troops.

In the present work we shall not examine the history of Tibet, which commences just at this time. It will be enough to note that about 650, the date at which we bring this narrative to a close, a new power had just arisen north of the Himalaya—a power which, from the very first, held a middle position between India and China, and welcomed Buddhism.

We leave an India which is once again falling to pieces, for Harsha's empire did not outlive its founder. The present lay with two very healthy reigning houses—the Chalukyas in the north-west of the Deccan and the Pallavas in the southeast. The future would be with the Mongols, and in part with Islam, for the year 622 saw the Hegira.

In the twelve or thirteen centuries of history which I have just sketched, in the broadest lines and with many gaps, is there any kind of unity?

That world of ancient India, we must repeat, is a chaos, because of differences of race and language and multiplicity of traditions and beliefs. Only in our own time have the reduction of distances by rapid communications and the imposition on all these alien peoples of a common tongue, English, given some homogeneity to the country. The chief unity which we find in the ages which we have so briefly described is that of the Vedic tradition imposed as Brahman orthodoxy by the Indo-European element. In politics the tradition of a King of Kings from time to time brings forth, in one place or another, a short-lived empire. But there is no local tradition to make such a power permanent. We have, indeed, seen interest centring on very different Indias in succession— the Punjab, the Ganges valley, the country of Ujjain, the Deccan.

Invasion from the north-west was an intermittent but chronic phenomenon. Sometimes it was new Indo-Europeans who came that way to reinforce the Aryans already settled in Hindustan, but sometimes it was Mongoloids, such as the Huns and the Turco-Mongols. Even in this latter case, no less than when the invaders were Greeks or Kushans, the new elements which attached themselves to the Hindu mass were, at least vaguely, Iranianized. In this way the invaders, even when not Indo-Europeans, continued and reinforced, and revived in unexpected forms, the ancient, permanent solidarity which united India to Iran, Without a doubt, we have here the most constant element in Indian history. From Iran came the claim to world-kingship, and there was a correlation between that supreme kingship and the favour shown to the only known religion which embraced all mankind.

Indeed, Buddhism rose to its greatest importance, not in India, but in the great Serindian spaces where it circulated from the Oxus to China. Græco-Parthians, Græco-Bactrians, Kushans, pre-Islamic Turco-Mongols, all the foreigners who set up their tents in Serindia before they established themselves in India itself, had more sympathy with an almost international religion than with Brahman orthodoxy, the social character of which was specially Hindu. That is why the great potentates belong to dynasties from outside, and why they combine with their temporal ambitions a devotion, the more sincere because it is interested, to Buddhism.

Lastly, we should note that the distinctions which we make in the West between antiquity and the Middle Ages, seen from the point of view of modern times, do not apply to Asia. Buddhism never brought in a new order, as Christianity did in the basin of the Mediterranean. In fact, it is one of the most ancient elements in the make-up of India, if we set aside Vedic prehistory, and it never conquered the whole of India, or anything like it. The invasions undergone by India and China did not introduce new institutions comparable to those which the Franks, for example, gave to Roman Gaul; much rather, they were remodelled in native forms. So there was no line between "antiquity" and "middle ages". In a sense, one might say that Asia was in all historical periods in a state comparable to the Middle Ages among ourselves, in that Asia always lived according to a traditional order, accompanied by a scholastic science. It was partly in order to make that continuity clear that I have carried our story down to the seventh century. My other reasons lie in the fact that ancient India then showed its fullest development, and that at this time a factor came into play which none could have forseen—the expansion of Islam.

1 Jouveau-Dubreuil, CXX.