WHILE it is true in general that among the various peoples the manifold functions of spiritual life, social or individual, only gradually break away from religion, it is particularly true of the civilization of India. Religion is, as it were, the common denominator, or the fundamental basis of all the factors which make up Indian life. In this second part we shall consider religion in its social aspect, deferring the examination of its individual aspect to the third part.

On the very threshold of the analysis of the religous institutions of ancient India which we have before us, we find once again the problems of the composition of the Indian world. We should be able to distinguish the Indo-European contribution from the earlier elements in which the Dravidian culture predominated. But to make this distinction, the materials are lacking.

Southern India, having been less thoroughly Aryanized than Northern, furnishes evidence about the Dravidian communities in the course of history and at this very day. But it would be very rash to venture to draw conclusions from it as to the social condition of the pre-Aryans who lived 1,500 or 2,000 years before our era. Lacking information about that non-Aryan India, we are reduced to the very arbitrary method of regarding as Dravidian those elements which are not drawn from the Vedic stock.

The Dravidians of antiquity, having left no written records, are only known to us through the Veda in the widest sense of the name. Since the Veda, is, to a still greater extent, the basis of our knowledge of classical India, the time has now come to give a brief abstract of it, without prejudice to the study of it to be made later with reference to literary history.

The Veda, in the widest sense, is not a collection of texts, but the sum of knowledge, by which one must understand all the arts and sciences required by religious life (dharma). In a stricter sense the word means a certain literature, which at first was handed down orally. In the most limited acceptation it stands for four collections (saṃhitā) of hymns and formulas, the first foundation of Vedic literature.

The four collections are as follows: Ṛigveda, a corpus of stanzas (ṛich) praising some deity; the Sāmaveda, a corpus of tunes to which the hymns of the first collection are to be sung; the Yajurveda, a corpus of sacrificial formulas in prose, mostly later than the hymns of the Ṛigveda; and the Atharvaveda, a corpus of magical recipes. The form of this fourth Veda, which follows that of the hymns of the first, shows that it is a later production, but its foundation belongs to an extremely ancient order of beliefs.

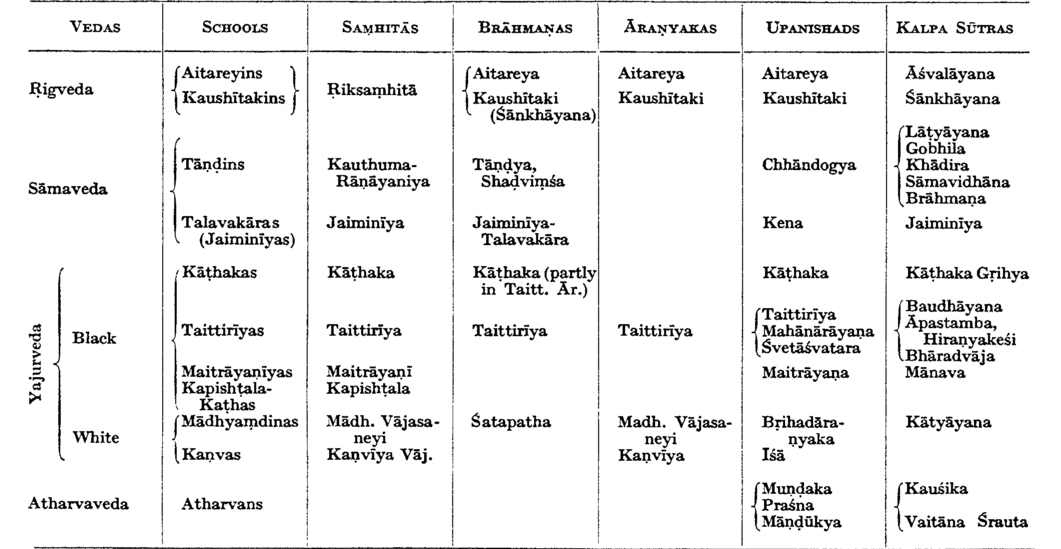

A secondary stratum of Vedic texts consists of commentaries, ritual (Brāhmaṇas) or metaphysical (Āraṇyakas, Upanishads), respectively intended to govern sacrifice and to transpose it into abstract speculation. Each is attached to one of the Vedas; the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa to the Ṛigveda, the Chhāndogya Upanishad to the Sāmaveda, others to one or the other of the two versions of the Yajurveda (for example, the Taittirīya and the Maitrāyaṇl Saṃhitā to the Black and the Vājaseneyi Saṃhitā to the White), and so on.

The Brāhmaṇas, which are in prose, contain rules for sacrificing, drawn up by priests for priests. Their great number points not only to diversity of sacrifices but to multiplicity of schools (śākhā).

The Āraṇyakas, or "Forest Books", are intended for the use of hermits living far from the world in the forest. Remote from the conditions of human life, ritual religion becomes no more than the symbol of transcendental truth, and normally these works lead on to the philosophy of the Upanishads. The table given opposite shows the connexion between these various kinds of work. This is an actual connexion in the case of the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, to which is attached an Aitareya Āraṇyaka containing an Aitareya Upanishad, and in the exactly parallel Kaushītaki and Taittirīya series. It is theoretic and artificial in other cases, for example in the connexion of many late Upanishads with the Atharvaveda.

A third stratum, comprising the six "limbs of the Veda" (vedānga) or sciences of exegetic interpretation—phonetics, ritual, grammar, etymology, metre, and astronomy1— consists of sūtras which are very brief mnemonic verses. This new literature, which is essentially scholastic, was learned by heart, and the prose explanations given by the master were intended to make the extremely condensed sentences intelligible. The Śrauta Sūtras give the rules for sacrifices; the Gṛihya Sūtras govern the sacraments (saṃskāra) which give a religious value to individual life from birth to death. These two classes of work together make up the whole corpus of ritual, Kalpa Sutra, and are supplemented by manuals giving the methods of mensuration and geometry needed for the preparation of the place of sacrifice and altar, the Śulva Sūtras. Other Sūtras lay down correct conduct in legal, moral, and religious matters; these are the Dharma Sūtras. Here again reality corresponds to theory only in part. In the Kātyāyana series, for example, there are only Śrantra and Śulva Sutras; in the Āśvalāyana series only Śrauta and Gṛihya Sūtras. Only the Āpastamba and the Baudhāyana series contain all four varieties of Kalpa Sūtra, the Śrauta, Gṛihya, Dharma, and Śulva Sūtras. In order not to complicate the table, these details are not given, nor those Sūtras which do not form part of the ritual (kalpa) properly so called.

1 Śikshā, kalpa, vyākaraṇa, nirukta, chhandas, jyotisha.