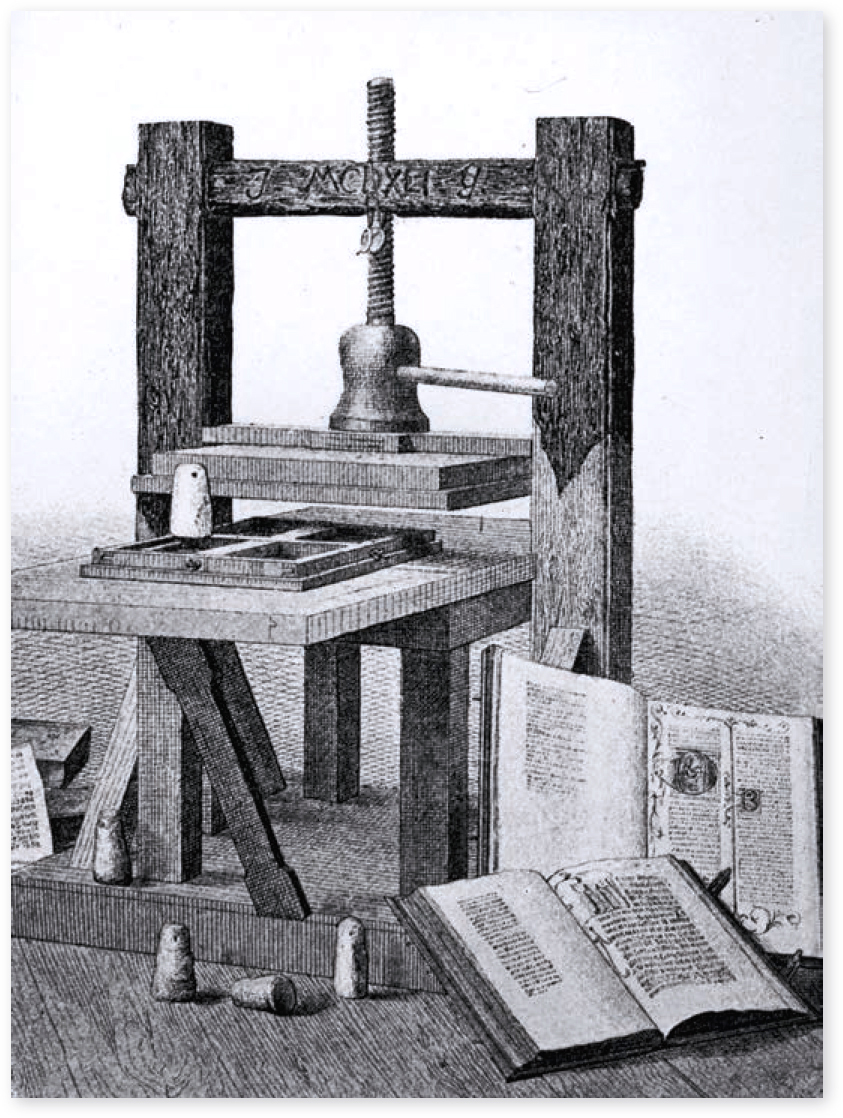

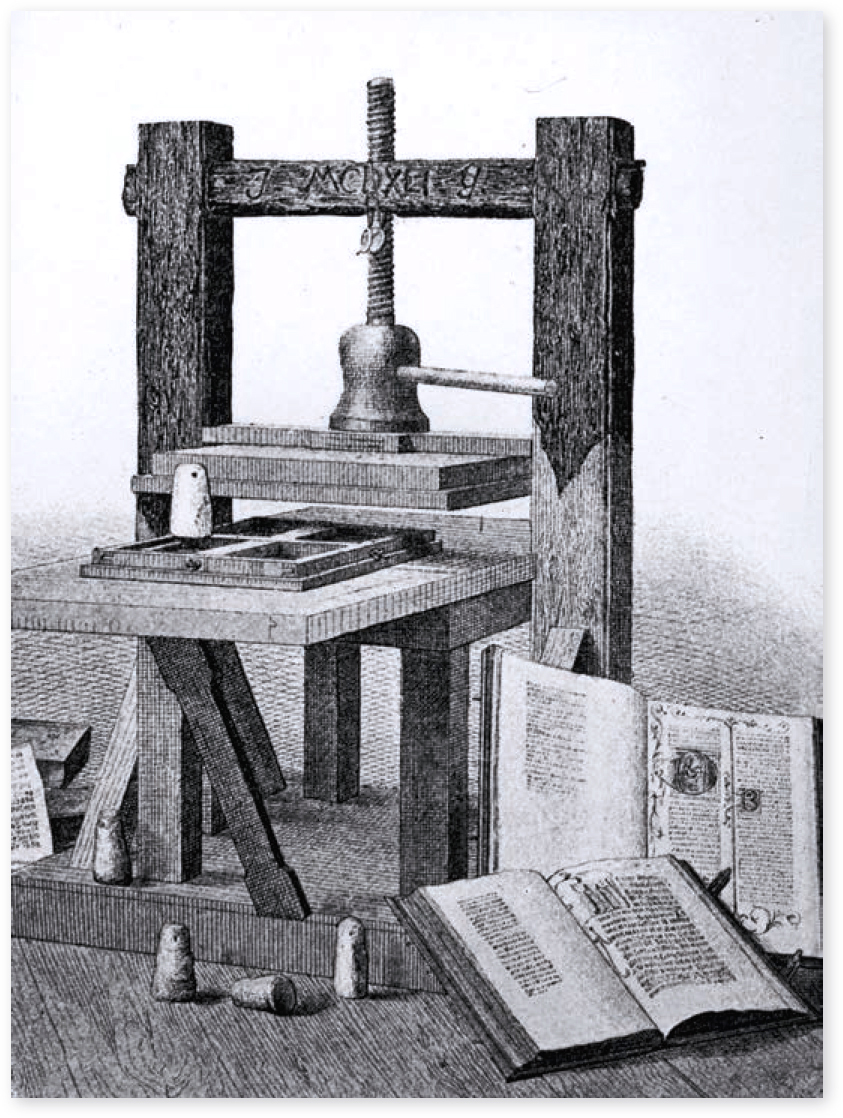

Printing presses, like this one shown in an old woodcut, are still used in a similar form by limited edition and art publishers today, emphasising their revolutionary capacity when first invented.

5 : Gutenberg printing press

1440

Printing presses, like this one shown in an old woodcut, are still used in a similar form by limited edition and art publishers today, emphasising their revolutionary capacity when first invented.

After little advancement of science during medieval times, scholars had some catching up to do. The first to seriously assimilate the findings of Aristotle and Pliny from the remaining translations of Arab, Greek and Roman precursors was William Turner.

A doctor and Northumberland native, Turner published the first printed book solely devoted to birds in 1544, with the unwieldy full title of Avium praecipuarum, quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, brevis et succincta historia – a short and succinct history of birds, most of which are mentioned in Pliny and Aristotle (see pages 18-19). Even as early as 1538, he had published his attempt at a full list of English flora and fauna, and such personal and public inventories are in some ways still widespread in modern birding.

A few other authors had briefly summarised ornithological knowledge beforehand within broader works, but Avium praecipuarum (written in exile, as Turner was a religious nonconformist) was a unique summary of ornithological knowledge at the time. This turning point in bird studies would not have been possible without a whole concatenation of previous communication innovations.

Mass-produced paper replaced parchment when water-powered paper mills were introduced around 1282, though paper had been manufactured in some form since the second century AD, initially in China. Bound books had evolved from Greek codices, and were commonplace in monasteries in the first few centuries of the Christian era in the West, and even some secular works were included in the libraries that began to be assembled during the sixth century.

The real revelation for written communication came with Johannes Gutenburg’s invention of the printing press around 1440 – for the first time it was possible to produce more than one copy of a work at the same time. This innovation was swiftly followed by a publishing industry which provided investment of capital and sales to a market of consumers, albeit only the few who had the money and education to be able to read. A variety of coloured inks enabled books to be profusely illustrated from the start.

Although he confused Bittern with White Pelican, it was also the inclusion of many of Turner’s own observations that made Avium praecipuarum a great leap forward, and the 16th century began to provide learned tomes for and by natural historians from then onwards, with works by Pierre Belon (France, 1555), Conrad Gessner (Germany, 1555), Volcher Coiter (Holland, 1575) and Ulisse Aldrovandi (Italy, 1603) in quick succession.

While much of the content of these first published works was apocryphal or folkloric, more was derived from field observations of European birds, and also from the first global forays of the Age of Exploration in Elizabethan times. With information and objects from the wider world pouring into Europe, the religious stranglehold over science and philosophy loosened and gradually allowed the first strained breaths of reason to be expelled through its fractured filter.

It is with the publication of Turner’s avian magnum opus, the first true bird book, that Britain can perhaps lay claim to being the birthplace of birding.