13

The Second World War

(1939–1945)

Stalin had always expected war to break out again in Europe. In every major speech on the Central Committee’s behalf he stressed the dangers in contemporary international relations. Lenin had taught his fellow communists that economic rivalry would pitch imperialist capitalist powers against each other until such time as capitalism was overthrown. World wars were inevitable in the meantime and Soviet foreign policy had to start from this first premiss of Leninist theory on international relations.

The second premiss was the need to avoid unnecessary entanglement in an inter-imperialist war.1 Stalin had always aimed to avoid risks with the USSR’s security, and this preference became even stronger at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in mid-1936.2 The dream of Maksim Litvinov, People’s Commissar for External Affairs, of the creation of a system of ‘collective security’ in Europe was dissipated when Britain and France refused to prevent Germany and Italy from aiding the spread of fascism to Spain. But what could Stalin do? Complete diplomatic freedom was unfeasible. But if he dealt mainly with the victor powers of the Great War, what trust could he place in their promises of political and military cooperation? If he attempted an approach to Hitler, would he not be rebuffed? And, whatever he chose to do, how could he maintain that degree of independence from either side in Europe’s disputes he thought necessary for the good of himself, his clique and the USSR?

Stalin’s reluctance to take sides, moreover, increased the instabilities in Europe and lessened the chances of preventing continental war.3 In the winter of 1938–9 he concentrated efforts to ready the USSR for such an outbreak. Broadened regulations on conscription raised the size of the Soviet armed forces from two million men under arms in 1939 to five million by 1941. In the same period there was a leap in factory production of armaments to the level of 700 military aircraft, 4,000 guns and mortars and 100,000 rifles.4

The probability of war with either Germany or Japan or both at once was an integral factor in Soviet security planning. It was in the Far East, against the Japanese, that the first clashes occurred. The battle near Lake Khasan in mid-1938 had involved 15,000 Red Army personnel. An extremely tense stand-off ensued; and in May 1939 there was further trouble when the Japanese forces occupied Mongolian land on the USSR–Mongolian border near Khalkhin-Gol. Clashes occurred that lasted several months. In August 1939 the Red Army went on to the offensive and a furious conflict took place. The Soviet commander Zhukov used tanks for the first occasion in the USSR’s history of warfare. The battle was protracted and the outcome messy; but, by and large, the Red Army and its 112,500 troops had the better of the Japanese before a truce was agreed on 15 September 1939.5

Hitler was active in the same months. Having overrun the Sudeten-land in September 1938, he occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, thereby coming closer still to the USSR’s western frontier. Great Britain gave guarantees of military assistance to Poland in the event of a German invasion. All Europe already expected Warsaw to be Hitler’s next target, and the USSR engaged in negotiations with France and Britain. The Kremlin aimed at the construction of a military alliance which might discourage Hitler from attempting further conquests. But the British in particular dithered over Stalin’s overtures. The nadir was plumbed in summer when London sent not its Foreign Secretary but a military attaché to conduct negotiations in Moscow. The attaché had not been empowered to bargain in his own right, and the lack of urgency was emphasized by the fact that he travelled by sea rather than by air.6

Whether Stalin had been serious about these talks remains unclear: it cannot be ruled out that he already wished for a treaty of some kind with Germany. Yet the British government had erred; for even if Stalin had genuinely wanted a coalition with the Western democracies, he now knew that they were not to be depended upon. At the same time Stalin was being courted by Berlin. Molotov, who had taken Litvinov’s place as People’s Commissar of External Affairs in May, explored the significance of the German overtures.7 An exchange of messages between Hitler and Stalin took place on 21 August, resulting in an agreement for German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop to come to Moscow. Two lengthy conversations occurred between Stalin, Molotov and Ribbentrop on 23 August. Other Politburo members were left unconsulted. By the end of the working day a Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Treaty had been prepared for signature.

This document had two main sections, one made public and the other kept secret. Openly the two powers asserted their determination to prevent war with each other and to increase bilateral trade. The USSR would buy German machinery, Germany would make purchases of Soviet coal and oil. In this fashion Hitler was being given carte blanche to continue his depredatory policies elsewhere in Europe while being guaranteed commercial access to the USSR’s natural resources. Worse still were the contents of the secret protocols of the Non-Aggression Treaty. The USSR and Germany divided the territory lying between them into two spheres of influence: to the USSR was awarded Finland, Estonia and Latvia, while Lithuania and most of Poland went to Germany. Hitler was being enabled to invade Poland at the moment of his choosing, and he did this on 1 September. When he refused to withdraw, Britain and France declared war upon Germany. The Second World War had begun.

Hitler was taken aback by the firmness displayed by the Western parliamentary democracies even though they could have no hope of rapidly rescuing Poland from his grasp. It also disconcerted Hitler that Stalin did not instantly interpret the protocol on the ‘spheres of influence’ as permitting the USSR to grab territory. Stalin had other things on his mind. He was waiting to see whether the Wehrmacht would halt within the area agreed through the treaty. Even more important was his need to secure the frontier in the Far East. Only on 15 September did Moscow and Tokyo at last agree to end military hostilities on the Soviet-Manchurian frontier. Two days later, Red Army forces invaded eastern Poland.

This was to Germany’s satisfaction because it deprived the Polish army of any chance of prolonging its challenge to the Third Reich and the USSR had been made complicit in the carving up of north-eastern Europe. While Germany, Britain and France moved into war, the swastika was raised above the German embassy in Moscow. Talks were resumed between Germany and the USSR to settle territorial questions consequent upon Poland’s dismemberment. Wishing to win Hitler’s confidence, Stalin gave an assurance to Ribbentrop ‘on his word of honour that the Soviet Union would not betray its partner’.8 On 27 September 1939, a second document was signed, the Boundary and Friendship Treaty, which transferred Lithuania into the Soviet Union’s sphere of interest. In exchange Stalin agreed to give up territory in eastern Poland. The frontier between the Soviet Union and German-occupied Europe was stabilized on the river Bug.

Stalin boasted to Politburo members: ‘Hitler is thinking of tricking us, but I think we’ve got the better of him.’9 At the time it seemed unlikely that the Germans would soon be capable of turning upon the USSR. Hitler would surely have his hands full on the Western front. Stalin aimed to exert tight control in the meantime over the sphere of interest delineated in the Boundary and Friendship Treaty. The governments of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were scared by Stalin and Molotov into signing mutual assistance treaties which permitted the Red Army to build bases on their soil.

On 30 November 1939, after the Finns had held out against such threats, Stalin ordered an invasion with the intention of establishing a Finnish Soviet government and relocating the Soviet-Finnish border northwards at Finland’s expense. Yet the Finns organized unexpectedly effective resistance. The Red Army was poorly co-ordinated; and this ‘Winter War’ cost the lives of 200,000 Soviet soldiers before March 1940, when both sides agreed to a settlement that shifted the USSR’s border further north from Leningrad but left the Finns with their independence. Thereafter Stalin sought to strengthen his grip on the other Baltic states. Flaunting his military hegemony in the region, he issued an ultimatum for the formation of pro-Soviet governments in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in June. Next month these governments were commanded, on pain of invasion, to request the incorporation of their states as new Soviet republics of the USSR. Also in July 1940, Stalin annexed Bessarabia and northern Bukovina from Romania.

The Sovietization of these lands was conducted with practised brutality. Leading figures in their political, economic and cultural life were arrested by the NKVD. Condemned as ‘anti-Soviet elements’, they were either killed or consigned to the Gulag. The persecution also affected less exalted social categories: small traders, school-teachers and independent farmers were deported to ‘special settlements’ in the RSFSR and Kazakhstan;10 4,400 captured Polish officers were shot and buried in Katyn forest. Thus the newly-conquered territory, from Estonia down to Moldavia, lost those figures who might have organized opposition to their countries’ annexation. A Soviet order was imposed. A communist one-party dictatorship was established, and factories, banks, mines and land were nationalized.

Stalin and his associates felt safe in concentrating on this activity because they expected the war in western Europe to be lengthy. Their assumption had been that France would defend herself doughtily against the Wehrmacht and that Hitler would be in no position to organize a rapid attack upon the Soviet Union. But Holland, Belgium, Denmark and Norway had already been occupied and, in June 1940, French military resistance collapsed and the British expeditionary forces were evacuated at Dunkirk. Even so, the USSR’s leadership remained confident. Molotov opined to Admiral Kuznetsov: ‘Only a fool would attack us.’11 Stalin and Molotov were determined to ward off any such possibility by increasing Soviet influence in eastern and south-eastern Europe. They insisted, in their dealings with Berlin, that the USSR had legitimate interests in Persia, Turkey and Bulgaria which Hitler should respect; and on Stalin’s orders, direct diplomatic overtures were also made to Yugoslavia.

But when these same moves gave rise to tensions between Moscow and Berlin, Stalin rushed to reassure Hitler by showing an ostentatious willingness to send Germany the natural materials, especially oil, promised under the two treaties of 1941. The movement of German troops from the Western front to the Soviet frontier was tactfully overlooked, and only perfunctory complaint was made about overflights made by German reconnaissance aircraft over Soviet cities. But Richard Sorge, a Soviet spy in the German embassy in Tokyo, told the NKVD that Hitler had ordered an invasion. Winston Churchill informed the Kremlin about what was afoot. Khrushchëv, many years later, recalled: ‘The sparrows were chirping about it at every crossroad.’12 Stalin was not acting with total senselessness. Hitler, if he planned to invade had to seize the moment before his opportunity disappeared. Both Soviet and German military planners considered that the Wehrmacht would be in grave difficulties unless it could complete its conquest of the USSR before the Russian snows could take their toll.

Convinced that the danger had now passed, Stalin was confident in the USSR’s rising strength. Presumably he also calculated that Hitler, who had yet to finish off the British, would not want to fight a war on two fronts by taking on the Red Army. In any case, the cardinal tenet of Soviet military doctrine since the late 1930s had been that if German forces attacked, the Red Army would immediately repel them and ‘crush the enemy on his territory’.13 An easy victory was expected in any such war; Soviet public commentators were forbidden to hint at the real scale of Germany’s armed might and prowess.14 So confident was Stalin that he declined to hasten the reconstruction of defences in the newly annexed borderlands or to move industrial plant into the country’s interior.

Throughout the first half of 1941, however Stalin and his generals could not overlook the possibility that Germany might nevertheless attempt an invasion. Movements of troops and equipment in German-occupied Poland kept them in a condition of constant nervousness. But Stalin remained optimistic about the result of such a war; indeed he and his political subordinates toyed with the project for the Red Army to wage an offensive war.15 At a reception for recently-trained officers in May 1941, Stalin spoke about the need for strategical planning to be transferred ‘from defence to attack’.16 But he did not wish to go to war as yet, and hoped against hope that an invasion by the Wehrmacht was not imminent. Soviet leaders noted that whereas the blitzkrieg against Poland had been preceded by a succession of ultimatums, no such communication had been received in Moscow. On 21 June Beria purred to Stalin that he continued to ‘remember your wise prophecy: Hitler will not attack us in 1941’.17 The brave German soldiers who swam the river Bug to warn the Red Army about the invasion projected for the next day were shot as enemy agents.

At 3.15 a.m. on 22 June, the Wehrmacht crossed the Bug at the start of Operation Barbarossa, attacking Soviet armed forces which were under strict orders not to reply to ‘provocation’. This compounded the several grave mistakes made by Stalin in the previous months. Among them was the decision to shift the Soviet frontier westward after mid-1940 without simultaneously relocating the fortresses and earthworks. Stalin had also failed to transfer armaments plants from Ukraine deeper into the USSR. Stalin’s years-old assumption prevailed that if and when war came to the Soviet Union, the attack would be quickly repulsed and that an irresistible counterattack would be organized. Defence in depth was not contemplated. Consequently no precautionary orders were given to land forces: fighter planes were left higgledy-piggledy on Soviet runways; 900 of them were destroyed in that position in the first hours of the German-Soviet war.18

Zhukov alerted Stalin about Operation Barbarossa at 3.25 a.m. The shock to Stalin was tremendous. Still trying to convince himself that the Germans were engaged only in ‘provocational actions’, Stalin rejected the request of D. G. Pavlov, the commander of the main forces in the path of the German advance, for permission to fight back. Only at 6.30 a.m. did he sanction retaliation.19 Throughout the rest of the day Stalin conferred frenetically with fellow Soviet political and military leaders as the scale of the disaster began to be understood in the Kremlin.

Stalin knew he had blundered, and supposedly he cursed in despair that his leadership had messed up the great state left behind by Lenin.20 The story grew that he suffered a nervous breakdown. Certainly he left it to Molotov on 22 June to deliver the speech summoning the people of the USSR to arms; and for a couple of days at the end of the month he shut himself off from his associates. It is said that when Molotov and Mikoyan visited his dacha, Stalin was terrified lest they intended to arrest him.21 The truth of the episode is not known; but his work-schedule was so intensely busy that it is hard to believe that he can have undergone more than a fleeting diminution of his will of steel to fight on and win the German-Soviet war. From the start of hostilities he was laying down that the Red Army should not merely defend territory but should counter-attack and conquer land to the west of the USSR. This was utterly unrealistic at a time when the Wehrmacht was crashing its way deep into Belorussia and Ukraine. But Stalin’s confirmation of his pre-war strategy was a sign of his uncompromising determination to lead his country in a victorious campaign.

The task was awesome: the Wehrmacht had assembled 2,800 tanks, 5,000 aircraft, 47,000 artillery pieces and 5.5 million troops to crush the Red Army. German confidence, organization and technology were employed to maximum effect. The advance along the entire front was so quick that Belorussia, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were under German occupation within weeks. The Russian city of Smolensk was overrun with a rapidity that left the party authorities no time to incinerate their files. By the beginning of September, the Wehrmacht had cut off Leningrad by land: transport to and from the Soviet Union’s second city had to be undertaken over Lake Ladoga. To the south, huge tracts of Ukraine were overrun: Kiev was captured in mid-August. After such success Hitler amassed his forces in the centre. In September, Operation Typhoon was aimed at the seizure of Moscow.

In the first six months of the ‘Great Fatherland War’, as Soviet leaders began to refer to the conflict, three million prisoners-of-war fell into German hands.22 There had been a massive loss to the USSR in its human, industrial and agricultural resources. Roughly two fifths of the state’s population and up to half its material assets were held under German dominion.

A political and military reorganization was rushed into place. For such a war, new forms of co-ordination had to be found. On 30 June it was decided to form a State Committee of Defence, bringing together leading Politburo members Stalin, Molotov, Beria, Malenkov and Voroshilov. The State Committee was to resolve all major political, economic and strategical questions and Stalin was appointed as its chairman. On 10 July he was also appointed Supreme Commander (although no immediate announcement was made since Stalin wanted to avoid being held popularly culpable for the continuing military débâcle). In addition, he became chairman of the High Command (Stavka) on 8 August.23 Stalin was attempting to be the Lenin and Trotski of the German-Soviet conflict. In the Civil War Lenin had operated the civilian political machinery, Trotski the military. Stalin wished to oversee everything, and dispatched several of his central civilian colleagues to secure his authority over the frontal commands.

It was a gruelling summer for the Red Army. The speed of the German invasion induced Stalin to contemplate moving the capital to the Volga city of Kuibyshev (once and now called Samara), 800 kilometres to the south-east of Moscow. Foreign embassies and several Soviet institutions began to be transferred. But suddenly in late October, the Wehrmacht met with difficulties. German forces on the outskirts of Moscow confronted insurmountable defence, and Stalin asked Zhukov whether the Red Army’s success would prove durable. On receiving the desired assurances from Zhukov, Stalin cancelled his emergency scheme to transfer the seat of government and intensified his demand for counter-offensives against the Wehrmacht.24

Hitler had already fallen crucially short of his pre-invasion expectations. His strategy had been based on the premiss that Moscow, Leningrad and the line of the river Volga had to be seized before the winter’s hard weather allowed the Red Army to be reorganized and re-equipped. The mud had turned to frost by November, and snow was not far behind. The supply lines of the Wehrmacht were overstretched and German soldiers started to feel the rigours of the Russian climate. Soviet resolve had already been demonstrated in abundance. On 3 July, Stalin made a radio-broadcast speech, addressing the people with the words: ‘Comrades! Citizens! Brothers and Sisters!’ He threatened the ‘Hitlerite forces’ with the fate that had overwhelmed Napoleon in Russia in 1812. ‘History shows,’ he contended, ‘that invincible armies do not exist and never have existed.’25 In the winter of 1941–2 his words were beginning to acquire a degree of plausibility.

Yet Stalin knew that defeat by Germany remained a strong possibility. Nor could he rid himself of worry about his own dreadful miscalculations in connection with Operation Barbarossa. On 3 October 1941 he blurted out to General Konev: ‘Comrade Stalin is not a traitor. Comrade Stalin is an honest person. Comrade Stalin will do everything to correct the situation that has been created.’26 He worked at the highest pitch of intensity, usually spending fifteen hours a day at his tasks. His attentiveness to detail was legendary. At any hint of problems in a tank factory or on a military front, he would talk directly with those who were in charge. Functionaries were summoned to Moscow, not knowing whether or not they would be arrested after their interview with Stalin. Sometimes he simply phoned them; and since he preferred to work at night and take a nap in the daytime, they grew accustomed to being dragged from their beds to confer with him.

As a war leader, unlike Churchill or Roosevelt, he left it to his subordinates to communicate with Soviet citizens. He delivered only nine substantial speeches in the entire course of the German-Soviet war,27 and his public appearances were few. The great exception was his greeting from the Kremlin Wall on 7 November 1941 to a parade of Red Army divisions which were on the way to the front-line on the capital’s outskirts. He spent the war in the Kremlin or at his dacha. His sole trip outside Moscow, apart from trips to confer with Allied leaders in Tehran in 1943 and Yalta in 1945, occurred in August 1943, when he made a very brief visit to a Red Army command post which was very distant from the range of gunfire.

The point of the trip was to give his propagandists a pretext to claim that he had risked his life along with his soldiers. Khrushchëv was later to scoff at such vaingloriousness; he also asserted – when Stalin was safely dead and lying in state in the Mausoleum on Red Square – that the office-based mode of leadership meant that Stalin never acquired a comprehension of military operations. The claim was even made by Khrushchëv that Stalin typically plotted his campaigns not on small-scale maps of each theatre of conflict but on a globe of the world. At best this was an exaggeration based upon a single incident. If anything, Stalin’s commanders found him excessively keen to study the minutiae of their strategic and tactical planning – and most of them were to stress in their memoirs that he gained an impressive technical understanding of military questions in the course of the war.

Not that his performance was unblemished. Far from it: not only the catastrophe of 22 June 1941 but several ensuing heavy defeats were caused by his errors in the first few months. First Kiev was encircled and hundreds of thousands of troops were captured. Then Red Army forces were entrapped near Vyazma. Then the Wehrmacht burst along the Baltic littoral and laid siege to Leningrad. All three of these terrible set-backs occurred to a large extent because of Stalin’s meddling. The same was true in the following year. In the early summer of 1942, his demand for a counter-offensive on German-occupied Ukraine resulted in the Wehrmacht conquering still more territory and seizing Kharkov and Rostov; and at almost the same time a similar débâcle occurred to the south of Leningrad as a consequence of Stalin’s rejection of Lieutenant-General A. N. Vlasov’s plea for permission to effect a timely withdrawal of his forces before their encirclement by the enemy.

Moreover, there were limits to Stalin’s military adaptiveness. At his insistence the State Committee of Defence issued Order No. 270 on 16 August 1941 which forbade any Red Army soldier to allow himself to be taken captive. Even if their ammunition was expended, they had to go down fighting or else be branded state traitors. There could be no surrender. Punitive sanctions would be applied to Soviet prisoners-of-war if ever they should be liberated by the Red Army from German prison-camps; and in the meantime their families would have their ration cards taken from them. Order No. 227 on 28 July 1942 indicated to the commanders in the field that retreats, even of a temporary nature, were prohibited: ‘Not one step backwards!’ By then Stalin had decided that Hitler had reached the bounds of his territorial depredation. In order to instil unequivocal determination in his forces the Soviet dictator foreclosed operational suggestions involving the yielding of the smallest patch of land.

Nor had he lost a taste for blood sacrifice. General Pavlov, despite having tried to persuade Stalin to let him retaliate against the German invasion on 22 June, was executed.28 This killing was designed to intimidate others. In fact no Red Army officer of Pavlov’s eminence was shot by Stalin in the rest of the German-Soviet war. Nor were any leading politicians executed. Yet the USSR’s leaders still lived in constant fear that Stalin might order a fresh list of executions. His humiliation of them was relentless. On a visit to Russia, the Yugoslav communist Milovan Djilas witnessed Stalin’s practice of getting Politburo members hopelessly drunk. At one supper party, the dumpy and inebriated Khrushchëv was compelled to perform the energetic Ukrainian dance called the gopak. Everyone knew that Stalin was a dangerous man to annoy.

But Stalin also perceived that he needed to balance his fearsomeness with a degree of encouragement if he was to get the best out of his subordinates. The outspoken Zhukov was even allowed to engage in disputes with him in Stavka. Alexander Vasilevski, Ivan Konev, Vasili Chuikov and Konstantin Rokossovski (who had been imprisoned by Stalin) were more circumspect in their comments; but they also emerged as commanders whose competence he learned to respect. Steadily, too, Stalin’s entourage was cleared of the less effective civilian leaders. Kliment Voroshilov, People’s Commissar for Defence, had been shown to have woefully outdated military ideas and was replaced. Lev Mekhlis and several other prominent purgers in the Great Terror were also demoted. Mekhlis was so keen on attack as the sole mode of defence in Crimea that he forbade the digging of trenches. Eventually even Stalin concluded: ‘But Mekhlis is a complete fanatic; he must not be allowed to get near the Army!’29

The premature Soviet counter-offensive of summer 1942 had opened the Volga region to the Wehrmacht, and it appeared likely that the siege of Stalingrad would result in a further disaster for the Red forces. Leningrad in the north and Stalingrad in the south of Russia became battle arenas of prestige out of proportion to their strategical significance. Leningrad was the symbol of the October Revolution and Soviet communism; Stalingrad carried the name of Lenin’s successor. Stalin was ready to turn either city into a Martian landscape rather than allow Hitler to have the pleasure of a victory parade in them.

Increasingly, however, the strength of the Soviet Union behind the war fronts made itself felt. Factories were packed up and transferred by rail east of the Urals together with their work-forces. In addition, 3,500 large manufacturing enterprises were constructed during the hostilities. Tanks, aircraft, guns and bullets were desperately needed. So, too, were conscripts and their clothing, food and transport. The results were impressive. Soviet industry, which had been on a war footing for the three years before mid-1941, still managed to quadruple its output of munitions between 1940 and 1944. By the end of the war, 3,400 military planes were being produced monthly. Industry in the four years of fighting supplied the Red forces with 100,000 tanks, 130,000 aircraft and 800,000 field guns. At the peak of mobilization there were twelve million men under arms. The USSR produced double the amount of soldiers and fighting equipment that Germany produced.

In November 1942 the Wehrmacht armies fighting in the outer suburbs of Stalingrad were themselves encircled. After bitter fighting in wintry conditions, the city was reclaimed by the Red Army in January 1943. Hitler had been as unbending in his military dispositions as Stalin would have been in the same circumstances. Field-Marshal von Paulus, the German commander, had been prohibited from pulling back from Stalingrad when it was logistically possible. As a consequence, 91,000 German soldiers were taken into captivity. Pictures of prisoners-of-war marching with their hands clasped over their heads were shown on the newsreels and in the press. At last Stalin had a triumph that the Soviet press and radio could trumpet to the rest of the USSR. The Red Army then quickly also took Kharkov and seemed on the point of expelling the Wehrmacht from eastern Ukraine.

Yet the military balance had not tipped irretrievably against Hitler; for German forces re-entered Kharkov on 18 March 1943. Undeterred, Stalin set about cajoling Stavka into attacking the Germans again. There were the usual technical reasons for delay: the Wehrmacht had strong defensive positions and the training and supply of the Soviet mobile units left much to be desired. But Stalin would not be denied, and 6,000 tanks were readied to take on the enemy north of Kursk on 4 July 1943. It was the largest tank battle in history until the Arab-Israeli War of 1967. Zhukov, who had used tanks against the Japanese at Khalkhin-Gol, was in his element. His professional expertise was accompanied by merciless techniques. Penal battalions were marched towards the German lines in order to clear the ground of land-mines. Then column after column of T-34 tanks moved forward. Red Army and Wehrmacht fought it out day after day.

The result of the battle was not clear in itself. Zhukov had been gaining an edge, but had not defeated the Wehrmacht before Hitler pulled his forces away rather than gamble on complete victory. Yet Kursk was a turning point since it proved that the victory at Stalingrad was repeatable elsewhere. The Red Army seized back Kharkov on 23 August, Kiev on 6 November. Then came the campaigns of the following year which were known as the ‘Ten Stalinist Blows’. Soviet forces attacked and pushed back the Wehrmacht on a front extending from the Baltic down to the Black Sea. Leningrad’s 900-day siege was relieved in January and Red forces crossed from Ukraine into Romania in March. On 22 June 1944, on the third anniversary of the German invasion, Operation Bagration was initiated to reoccupy Belorussia and Lithuania. Minsk became a Soviet city again on 4 July, Vilnius on 13 July.

As the Red Army began to occupy Polish territory, questions about the post-war settlement of international relations imprinted themselves upon Soviet actions. On 1 August the outskirts of Warsaw were reached; but further advance was not attempted for several weeks, and by that time the German SS had wiped out an uprising and exacted revenge upon the city. About 300,000 Poles perished. Stalin claimed that his forces had to be rested before freeing Warsaw from the Nazis. His real motive was that it suited him if the Germans destroyed those armed units of Poles which might cause political and military trouble for him.

The USSR was determined to shackle Poland to its wishes. In secret, Stalin and Beria had ordered the murder of nearly 15,000 Polish officers who had been taken captive after the Red Army’s invasion of eastern Poland in 1939. Subsequently Soviet negotiators had been suspiciously evasive on the question of Poland’s future when, in July 1941, an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed; and the British government, which faced a dire threat from Hitler, had been in no position to make uncompromising demands in its talks with Stalin. Nor was Stalin any more easily controllable when the USA entered the Second World War in December 1941 after Japan’s air force attacked the American fleet in Pearl Harbor and Hitler aligned himself with his Japanese partners against the USA. The USSR’s military contribution remained of crucial importance when the Anglo-Soviet-German war in Europe and the Japanese war of conquest were conjoined in a single global war.

There was an exception to Stalin’s chutzpah. At the end of 1941 he had ordered Beria to ask the Bulgarian ambassador Ivan Stamenov to act as an intermediary in overtures for a separate peace between the USSR and Germany.30 Stalin was willing to forgo his claims to the territory under German occupation in exchange for peace. Stamenov refused the invitation. Stalin would anyway not have regarded such a peace as permanent. Like Hitler, he must have calculated that the Wehrmacht’s cause was ultimately lost if Leningrad, Moscow and the Volga remained under Soviet control. A ‘breathing space’ on the model of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk would have been more advantageous to Stalin in 1941–2 than to Lenin in 1918.

Naturally Stalin kept this gambit secret from the Western Allies; and through 1942 and 1943, he expressed anger about the slowness of preparations for a second front in the West. Churchill flew to Moscow in August 1942 to explain that the next Allied campaign in the West would be organized not in France or southern Italy but in north Africa. Stalin was not amused. Thereafter a meeting involving Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin was held in Tehran in November 1943 – the greatest distance Stalin had travelled from Moscow in three decades. Churchill flew again to Moscow in October 1944, and in February 1945 Stalin played host to Roosevelt and Churchill at Yalta in Crimea. At each of these meetings, he drew attention to the sacrifices being borne by the peoples of the USSR. Not even the D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944 put an end to his habit of berating the other Allies; for he knew that his complaints about them served the purpose of distracting attention from his designs upon eastern Europe.

All this notwithstanding, Stalin had been receiving considerable military and foodstuffs assistance from the USA and the United Kingdom to plug the gaps in Soviet production. The German occupation of Ukraine deprived the USSR of its sugar-beet. Furthermore, Stalin’s pre-war agricultural mismanagement had already robbed the country of adequate supplies of meat; and his industrial priorities had not included the development of native equivalents to American jeeps and small trucks. In purely military output, too, misprojections had been made: the shortage of various kinds of explosive was especially damaging.

From 1942, the Americans shipped sugar and the compressed meat product, Spam, to Russia – and the British naval convoys braved German submarines in the Arctic Ocean to supplement supplies. Jeeps, as well as munitions and machinery, also arrived. The American Lend-Lease Programme supplied goods to the value of about one fifth of the USSR’s gross domestic product during the fighting – truly a substantial contribution.31 Yet Allied governments were not motivated by altruism in dispatching help to Russia: they still counted upon the Red Army to break the backbone of German armed forces on the Eastern front. While the USSR needed its Western allies economically, the military dependence of the USA and the United Kingdom upon Soviet successes at Stalingrad and Kursk was still greater. But foreign aid undoubtedly rectified several defects in Soviet military production and even raised somewhat the level of food consumption.

There was a predictable reticence about this in the Soviet press. But Stalin and his associates recognized the reality of the situation; and, as a pledge to the Western Allies of his co-operativeness, Stalin dissolved the Comintern in May 1943. Lenin had founded it in 1919 as an instrument of world revolution under tight Russian control. Its liquidation indicated to Roosevelt and Churchill that the USSR would cease to subvert the states of her Allies and their associated countries while the struggle against Hitler continued.

While announcing this to Churchill and Roosevelt, Stalin played upon their divergent interests. Since Lenin’s time it had been a nostrum of Soviet political analysis that it was contrary to the USA’s interest to prop up the British Empire. Roosevelt helped Stalin by poking a little fun at Churchill and by turning his charm upon Stalin in the belief that the USSR and USA would better be able to reach a permanent mutual accommodation if the two leaders could become friendlier. But Stalin remained touchy about the fact that he was widely known in the West as Uncle Joe. He was also given to nasty outbursts. Churchill walked out of a session at the Tehran meeting when the Soviet leader proposed the execution of 50,000 German army officers at the end of hostilities. Stalin had to feign that he had not meant the suggestion seriously so that the proceedings might be resumed.

At any rate, he usually tried to cut a genial figure, and business of lasting significance was conducted at Tehran. Churchill suggested that the Polish post-war frontiers should be shifted sideways. The proposal was that the USSR would retain its territorial gains of 1939–40 and that Poland would be compensated to her west at Germany’s expense. There remained a lack of clarity inasmuch as the Allies refused to give de jure sanction to the forcible incorporation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania into the USSR. But a nod and a wink had been given that the Soviet Union had special interests in parts of eastern Europe that neither Britain nor the USA cared to challenge.

This conciliatory approach was maintained in negotiations between Churchill and Stalin in Moscow in October 1944. Japan had not yet been defeated in the East, and the A-bomb stayed at an early experimental stage. Germany was still capable of serious counter-offensives against the Allied armies which were converging on the Third Reich. It made sense to divide German-occupied Europe into zones of influence for the immediate future. But Churchill and Stalin could not decide how to do this; each was reluctant to let the other have a completely free hand in the zone accorded to him. On his Moscow trip, therefore, Churchill put forward an arithmetical solution which appealed to Stalin. It was agreed that the USSR would gain a ninety per cent interest in Romania. She was also awarded seventy-five per cent in respect of Bulgaria; but both Hungary and Yugoslavia were to be divided fifty-fifty between the two sides and Greece was to be ninety per cent within the Western zone.

Very gratifying to Stalin was the absence of Poland from their agreement, an absence that indicated Churchill’s unwillingness to interfere directly in her fate. Similarly Italy, France and the Low Countries were by implication untouchable by Stalin. Yet the understanding between the two Allied leaders was patchy; in particular, nothing was agreed about Germany. To say the least, the common understanding was very rough and ready.

But it gave Stalin the reassurance he sought, and he scrawled a large blue tick on Churchill’s scheme. The interests of the USSR would be protected in most countries to Germany’s east while to the west the other Allies would have the greater influence. Churchill and Stalin did not specify how they might apply their mathematical politics to a real situation. Nor did they consider how long their agreement should last. In any case, an Anglo-Soviet agreement was insufficient to carry all before it. The Americans were horrified by what had taken place between Churchill and Stalin. Zones of influence infringed the principle of national self-determination, and at Yalta in February 1945 Roosevelt made plain that he would not accede to any permanent partition of Europe among the Allies.

But on most other matters the three leaders could agree. The USSR contracted to enter the war against Japan in the East three months after the defeat of Germany. Furthermore, the Allies delineated Poland’s future borders more closely and decided that Germany, once conquered, should be administered jointly by the USSR, USA, Britain and France.

Stalin saw that his influence in post-war Europe would depend upon the Red Army being the first force to overrun Germany. Soviet forces occupied both Warsaw and Budapest in January 1945 and Prague in May. Apart from Yugoslavia and Albania, every country in eastern Europe was liberated from German occupation wholly or mainly by them. Pleased as he was by these successes, his preoccupation remained with Germany. The race was on for Berlin. To Stalin’s delight, it was not contested by the Western Allies, whose Supreme Commander General Eisenhower preferred to avoid unnecessary deaths among his troops and held to a cautious strategy of advance. The contenders for the prize of seizing the German capital were the Red commanders Zhukov and Konev. Stalin called them to Moscow on 3 April after learning that the British contingent under General Montgomery might ignore Eisenhower and reach Berlin before the Red Army. The Red Army was instructed to beat Montgomery to it.

Stalin drew a line along an east-west axis between the forces of Zhukov and Konev. This plan stopped fifty kilometres short of Berlin. The tacit instruction from Stalin was that beyond this point whichever group of forces was in the lead could choose its own route.32 The race was joined on 16 April, and Zhukov finished it just ahead of Konev. Hitler died by his own hand on 30 April, thwarting Zhukov’s ambition to parade him in a cage on Red Square. The Wehrmacht surrendered to the Anglo-American command on 7 May and to the Red Army a day later. The war in Europe was over.

According to the agreements made at Yalta, the Red Army was scheduled to enter the war against Japan three months later. American and British forces had fought long and hard in 1942–4 to reclaim the countries of the western coastline of the Pacific Ocean from Japanese rule; but a fierce last-ditch defence of Japan itself was anticipated. Harry Truman, who became American president on Roosevelt’s death on 11 April, continued to count on assistance from the Red Army. But in midsummer he abruptly changed his stance. The USA’s nuclear research scientists had at last tested an A-bomb and were capable of providing others for use against Japan. With such a devastating weapon, Truman no longer needed Stalin in the Far East, and Allied discussions became distinctly frosty when Truman, Stalin and Churchill met at Potsdam in July. On 6 August the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, on 9 August a second fell on Nagasaki.

Yet Stalin refused to be excluded from the war in the Far East. Alarmed by the prospect of a Japan exclusively under American control, he insisted on declaring war on Japan even after the Nagasaki bomb. The Red Army invaded Manchuria. After the Japanese government communicated its intention to offer unconditional surrender, the USA abided by its Potsdam commitment by awarding southern Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands to the Soviet Union. Thus the conflict in the East, too, came to an end. The USSR had become one of the Big Three in the world alongside the United States of America and the United Kingdom. Her military, industrial and political might had been reinforced. Her Red Army bestrode half of Europe and had expanded its power in the Far East. Her government and her All-Union Communist Party were unshaken. And Stalin still ruled in the Kremlin.

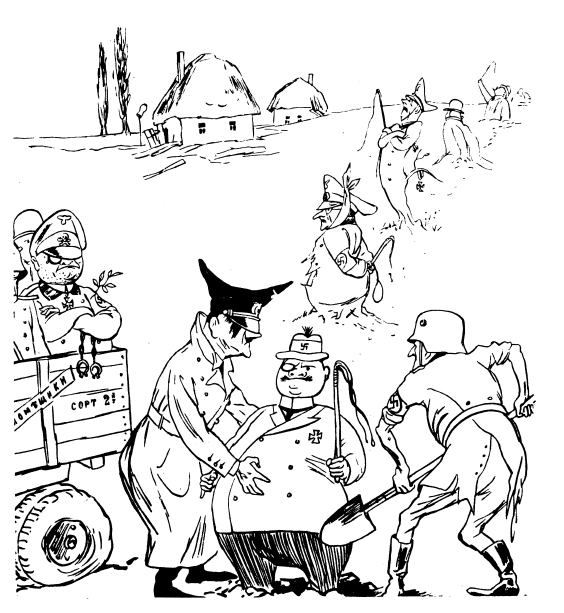

‘Spring Sowing in Ukraine.’

A cartoon (1942) showing Hitler and a German soldier planting a whip-carrying German government official in a Ukrainian village.