2

Creating a Newspaper Colony

It was an ingenious idea, and by the time the system was employed to create Pell Lake in 1924, the subscription premium real estate promotion had ripened and matured.

Pells Lake in Walworth County perfectly matched the Smadbeck template both in character and location. Covering about 100 acres, the lake was a favorable size with a partial sand bottom and two natural beaches. Surrounded by farmland for miles in every direction, it was located only a short train ride from Chicago, where a ready supply of working-class buyers resided. The abundant areas of swamp could be dealt with.

The two brothers operated through dozens of corporate entities but they also bought and sold realty in their own names as they did with the land in Wisconsin. While they worked closely together, they nevertheless handled their own projects, and Pells Lake was pursued by the dentist, Dr. Warren Smadbeck. Once he chose the location, Dr. Smadbeck began implementing the project with a sophistication that demonstrated an already well-established framework. He quickly found it convenient to drop the final “s” on the name of the lake thereby establishing “Pell Lake” as the title of his development and also altering, and solidifying, the name of the lake itself.1

The land was acquired using a trusted buying agent who could travel to the location and negotiate with the titleholders on Smadbeck’s behalf. Ludwig B. Freudenthal, of Jersey City, New Jersey, the son of Warren’s great-uncle Julius Freudenthal,2 and a first cousin to Warren’s father, was the agent employed for this purpose at Pell Lake. The first purchases, from Ed Holtzheimer and Charles Kull, took place on April 7, 1924.3 More land was bought from Kull, James Reeves, and Harriet Hibbard in July and August, all of which was purchased by Freudenthal in his own name.4 Ludwig then reassembled the acreage and deeded it to Warren Smadbeck in eight parcels.5 Before the end of the year, Smadbeck had title to over 700 acres, comprising nearly all of the land immediately surrounding the lake.

Dr. Smadbeck acquired other rights to the lake as well. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries surface ice was cut from southern Wisconsin lakes, especially those with access to a rail line, and Pells Lake was no exception. Ice was harvested during the winter months and stored in ice houses for shipment to Chicago in warmer times for use in the meat and produce markets.6 But with broadening access to mechanical refrigeration and the resulting ability to artificially produce ice, the demand for harvested ice had drastically declined by 1924. This enabled Smadbeck to purchase the right to harvest ice from Pells Lake as well as riparian rights to the small parcel of waterfront property owned by the ice company, ensuring that nothing would conflict with the planned recreational usage.7

Smadbeck knew how to improve an imperfect body of water and Pell Lake was particularly problematical. To the north lay a swath of swamp larger than the lake itself, another wetland area to the south, and the entire western and southern shores were lined with marshes. The land around the lake would be more salable if some of these low and swampy portions could be eliminated, or at least camouflaged. Smadbeck had several tools available to accomplish this—dams, drainage, ditches, and dredging—all of which were employed at Pell Lake.

Seeking to raise the water level in the lake by three feet, he built a low dam at the southeastern end of the lake where it drained off into Nippersink Creek. Then he diverted some of the swamp drainage with ditches and conduits. When these measures did not adequately maintain the higher lake level, he engaged Davis Construction, an Iowa company, to dredge 30 acres of swamp on the south and west sides, a job that took several months.8

Arthur King was engaged to survey the land and prepare plat maps according to Smadbeck’s specifications, subdividing the 700 acres into 9,799 lots. These plats were presented to the Bloomfield Town Board for its consideration by local attorney Sturges P. Taggart. A total of seven numbered and two lettered sections were approved at six separate sessions of the town board between July 16 and October 10, 1924, with Dr. Smadbeck present at each of the meetings.9

Typically, the lot pattern was a rectangle containing fifty or so lots in the center, each 20' wide and 100' deep, laid out back to back with another ten lots positioned crosswise along each end. This novel lot configuration serves to identify later resort developments as replicas of the Smadbeck plan. The plat maps were reproduced on large sheets of paper each bearing two or more sections and printed on both sides of the sheet. These maps were specifically created for use by the sales staff to assist buyers in selecting their lots.

The C and NW Railway was easily persuaded to add a stop at Pell Lake since a resort settlement would increase ridership on an already well-established route. The railway built a depot and train service to the lake began on July 5, 1924, before any of the land plats had been approved.10 Roadways from Chicago were not yet entirely paved but with the increasing popularity of automobiles they would continue to improve.

Two lumber companies, Taggart and Zenda, established yards at Pell Lake to supply building materials and, by 1925, a third lumberyard had opened11 along with four construction companies and three stores.12 Smadbeck arranged for the Southern Wisconsin Electric Light Company to provide electricity to the area during limited hours.13

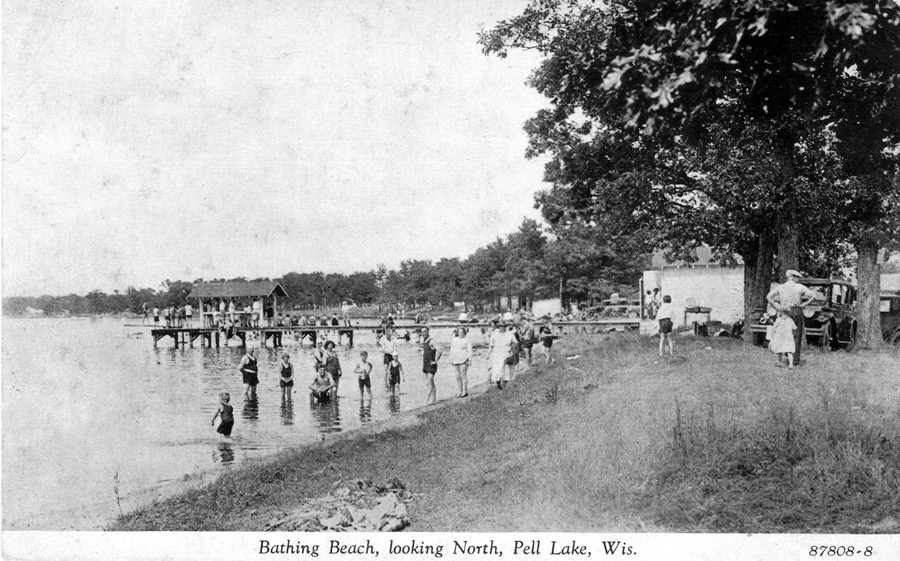

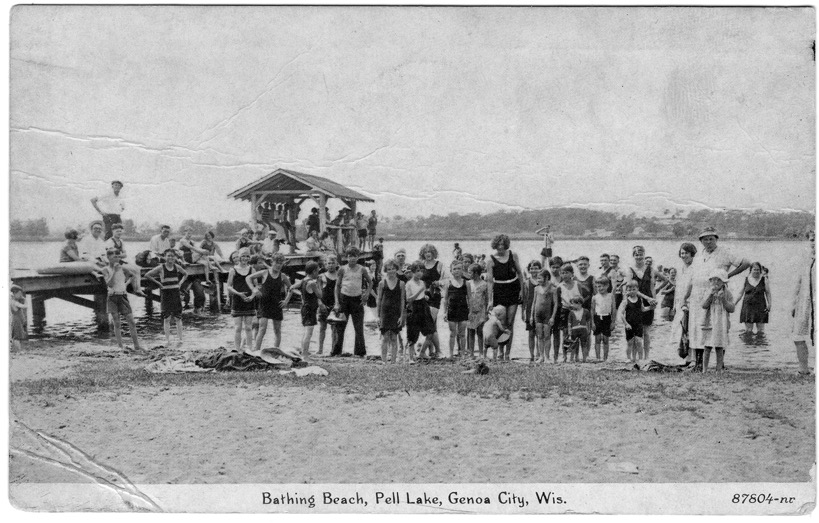

Land along the lake shore had been designated for parks and beaches and a block of lots was set aside for a clubhouse. Piers, floating rafts, beach shelters, and other structures were built for the use of the residents. In the spring of 1926 Pell Lake was sufficiently developed to justify the commissioning of a post office and 32-year-old August E. Wachtel was appointed as the first postmaster on April 3.14 The post office was housed in Wachtel’s general store located near the train station.

August Wachtel opened “Your Store” shown here in 1925. Writing on the building advertises ice cream, soft drinks, candy, and cigarettes. Wachtel and his family lived in the house next to the store. The train depot can be seen in the background.

By 1928 the Wachtel house had been elevated on stone blocks and the store and post office moved to the newly created ground level. A blue and yellow Dixie Gas pump sits out front.

Two years later a Catholic church was established when Saint Mary’s of the Lake opened in July of 1928.15 Eventually a church building was constructed on land owned by George Sitterle on North Lake Shore Drive not far from Clover Road.

* * *

All of the careful preparation to make the site visually and functionally attractive was only part of the undertaking—equally important was the alliance with the newspaper. The interaction between these two components was carefully choreographed. Long before Smadbeck began looking for a suitable location for a summer resort in southern Wisconsin he had the promotional arrangement lined up with the Chicago Evening Post. The initial advertisement for Pell Lake, a two-pager, appeared in the Post on Wednesday, July 16, 1924, the very day that the first of the land plats was approved. It was billed as “The Greatest Subscription Premium Offer Ever Made.” Readers could buy a lot for $67.50 with the purchase of a six-month subscription to the newspaper. Installment terms were $10 down and $2.50 a month. While the lot size was not mentioned, the ad emphasized that the purchase price included use of the lake, bathhouses, and beaches, lifetime membership in the clubhouse, and exclusive rights, along with the other property owners, to the parks along the lakeshore.

The south beach at Pell Lake had a beach house and outdoor privies. A crude shelter and a diving board were attached to the end of the pier.

The advertising campaign was fashioned to generate a buying fever, a goal that was masterfully accomplished with lots in the subdivision selling at lightning speed. Several articles in the local newspaper credited Pell Lake with initiating a resort boom in Walworth County. “Twenty-Eight Subdivisions on Walworth County Lakes”16 singled out Pell Lake as the largest of the many summer colonies in the process of development. “Wisconsin’s Land Boom”17 predicted that the climax of the boom in Florida was causing developers to seek new areas to conquer, suggested that Walworth County presented a ripe plum, and cited Pell Lake as an example. In “Talk About Sunny Florida; Take a Look at Pell Lake Resort”18 a direct parallel was drawn between the dramatic development of Pell Lake and land speculation in Florida.

The Pell Lake Property Owners Association (POA) was organized toward the end of 1925,19 and two months later, the parkland and the clubhouse site were deeded to the association.20 In February of 1927, Warren Smadbeck quietly transferred approximately 1,300 unsold lots to Matthew Jonap.21 More than 8,000 lots had been sold to newspaper readers and the Chicago Evening Post had increased its subscription base by an equal number. In less than three years, from start to finish, Pell Lake was virtually complete.

* * *

Pell Lake was so successful, so quickly, it spawned copycats immediately. Farmers who either refused to sell their land or were not made an offer sought to ride on the coattails of Smadbeck by capitalizing on the extensive advertising and built up mania.

Less than a month after the final plat hearing for Smadbeck’s Pell Lake, George Sitterle obtained approval for a block of lots north of the lake. He platted a second adjoining parcel in 1925 and these became Sitterle’s Subdivision and Addition.22 It consisted of a strip of land on the north side of Lake Shore Drive running west to Clover Road, and then up the hill along the right side of Clover. Sitterle offered about 100 lots of varying sizes.

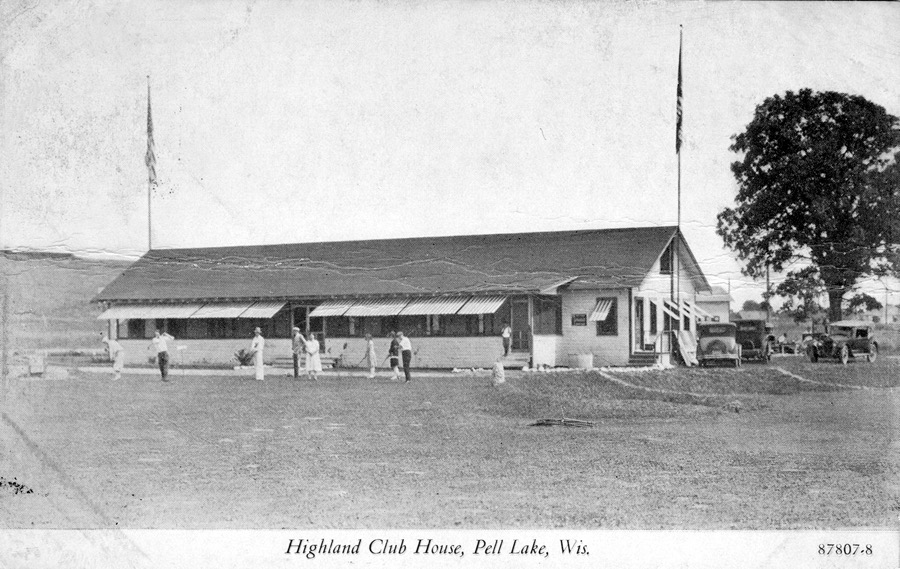

Sitterle’s lots were a minor adjunct compared with the Highlands and the Addition, both subdivided in the summer of 1925 by Chicago real estate men. Earl McDonald and Clifford Osborne, operating as Land O Lakes Resort Company, platted out 1,600 lots in Pell Lake Highlands creeping uphill on the other side of Clover Road from Sitterle.23 This 125-acre tract had been used as a dairy farm by the seller, Lewis Kimball, who reserved 12 acres in the center of the section for himself including the residence and the orchard.24 The land was disadvantaged by being at a distance from the beaches and separated from the main development by Clover Road. It was also handicapped by having no relationship with a big city newspaper other than small classified ads appearing in the Chicago Daily Tribune. Land O Lakes could not offer use of Smadbeck’s clubhouse and so instead promoted free membership in a golf club.

The Highland Golf Course and Tennis Courts opened to the public in July of 1926. Dances were held every Saturday night in the Highland Club House.

Pell Lake Addition more successfully blended in with the Smadbeck development. Leon Sex25 and Frank Sampson formed Pell Lake Development and created 1,488 lots on level land immediately east of Smadbeck’s tract.26 Sex announced that twenty lots at the corner of Daisy and Marinette would be the site of a $40,000 hotel with a dining room, game rooms, and club rooms.27 The plats also set aside an area for a golf course just off the southeast corner of the Addition.

Large display ads appearing in the Chicago Evening Post borrowed heavily from those of the Smadbecks with the same pricing terms and emphasizing that the Addition was adjacent to the Post’s development. There was no subscription tie-in but readers of the paper were told to “Follow the Blue Arrows” just as Smadbecks’ ads for Pell Lake had done.28 Both Pell Lake Highlands and the Pell Lake Addition copied the Smadbeck lot size and layout design.

Another small, but somewhat significant, addition attached itself to Pell Lake in the summer of 1925. Ira Pell’s original farmland was owned by Andrew Hafs and a house located there known as the “Pell House” burned in February of 1925.29 Hafs laid out a row of sixty-five lots along the southern edge of his property which included the site of the burned house. Christened “Pell Farm Annex to Pell Lake Summer Resort,” it consumed less than three of Pell’s original 80 acres and was the only part of Ira Pell’s farm to be associated with the Pell Lake development.30 While Pell Lake, an unincorporated area of Bloomfield Township, had no defined borders, the Smadbeck plats, Sitterle’s lots, the Highlands, the Addition, and the Pell Farm Annex comprised the core and substance of Pell Lake for many decades.

* * *

The advertising campaign encouraged everyone to visit Pell Lake, including potential lot buyers, those who had already purchased lots at the Post’s office in Chicago, friends and relatives of both groups, and the general public. In the 1920s getting there was half the fun. Instead of offering free transportation to the resort, advertisements contained a full print out of C and NW’s newly created schedule for trains between Chicago and Pell Lake. Those who came by rail rubbed elbows with wealthier Chicagoans before departing the train just one stop before prestigious Lake Geneva, thus giving Pell Lake a special panache.

Car travel was somewhat less reliable. The advertisements provided a map with mile by mile, turn by turn, driving directions often keyed to where concrete roads began, ended, and began again.31 Large blue arrows were posted along the route as a further guide. The poor driving conditions and early car design caused recurrent flat tires which provided added excitement for those who reveled in the adventure. Once drivers arrived in Pell Lake they found roads that were little better than dirt trails. People packed picnic lunches and came on day outings for sun and water sports. As the promoters urged, many who visited ended up buying lots. They in turn showed them off to their friends, some of whom were also caught up in the lot-buying madness. The sale of lots took hold quickly with the lots selling at a rapid pace.

Pell Lake is seen here at a very early stage in its development. This photograph, looking southeast, was taken from the crest of the hill on Clover Road in 1924 or 1925.

Before their cottages were built these Pel-Lakens, members of a club for young people, pitched tents and took the seats out of their cars to use as mattresses.

The fun-lovers made quick use of their investment, initially setting up tents for overnight stays. Outhouses were among the first structures to be built, but soon construction of cottages began. The early houses were simple structures, meant for summer living. If cottages had both inside and outside walls, the insulation between them consisted of newspapers which the lot owners had a steady supply of after buying several subscriptions to the Post. Most cottages were the same design—a rectangle with a kitchen, living room, two bedrooms, and a screened porch usually fitted out with hand-me-down furniture from the city dwelling. The shutters on the windows were held open with sticks in nice weather and closed and latched with bow tie turn buttons for the winter. A well dug near the kitchen door was operated by a hand water pump.

Many bungalows were built by the land owners themselves using whatever scrap materials they could find. One man, a worker in the produce market in Chicago, salvaged fruit crates and brought them out to Pell Lake piled atop his Model T. This wood became the walls of his cottage and the house never stopped smelling of citrus on hot, humid summer days.32 Another lot buyer from the city salvaged hundreds of paving bricks when the streetcar tracks were removed from Cicero Avenue. These were used to create a pathway from the back door of his cottage to the outhouse at the back of the lot.

This typical cottage was shipped out in pre-cut pieces on the railroad to be assembled by the lot owner whose name was imprinted on the attic rafters. The hand pump for water can be seen just to the left of the bungalow (see arrow).

A view of the back of the cottage shows the brick path leading to the outhouse. Scythes and rakes were used to tame the tall weeds until a lawn could be established.

Some bungalows were precut and shipped out on the railroad in kits for the home owner to assemble. These prepackaged cottages can be identified today by the names of purchasers stamped or stenciled on attic rafters. The more substantial cottages were constructed by local builders and lumberyards. A. Blackstone of Chicago had a contract to build five hundred summer homes at Pell Lake, more than a hundred of which had been constructed by June of 1925.33

The lake was stocked with fish, making boating and fishing popular activities with rowboats and canoes lining the shore. Children were kept occupied swimming all day in the lake while their parents chatted with new neighbors. Evenings were filled with dancing and parties. Milk, eggs, and vegetables could be bought from nearby farmers and the country air was refreshing.

Many of the lot buyers, those caught up in the mystique of getting a piece of land at a bargain price but lacking the gumption to follow through with the dream of a summer home, never even ventured to Pell Lake, buying their lots from a map with little cognizance of where the plot was in relation to the lake or the beaches. Still, enough lot buyers came, built cottages, and vacationed to cause excitement among Lake Geneva merchants. With the summer population swelling by 1,000 to 1,500 people the lumber dealers, hardware stores, furniture dealers, and dry goods merchants looked forward to increased business.34 They were not disappointed. Grocers, meat markets, and milk dealers all reported a banner season in 1926.

The railroad set a new record for summer travel averaging around 700 rail passengers a day, and on at least one occasion, handling twice that number. There was a reciprocal increase in freight shipments, especially lumber. The telegraph and post office also handled an overflow of business and the newspaper dealers reported a record year for the sale of Chicago papers.35 Even the county benefited when its tax rolls increased by $48,000 attributable to the development of Pell Lake.36

With Pell Lake the newspaper deal had reached its epitome. All the resorts created before Pell Lake were a prelude to this platform of achievement and, due to changing laws and economies, none of the newspaper developments that came after it would realize the same degree of accomplishment.

Swimmers crowd the south beach at Pell Lake. Postcards of the colony provided lot owners and visitors with an easy means of writing to city friends about their happy vacations.

The lot buying common folk were having a good time with their new adventure. Pell Lake was fun. It was the Roaring Twenties and Pell Lake was a roaring success.

1. The local newspaper began incorporating the name change into its news reports in late October 1924. Compare “Linn-Bloomfield,” Lake Geneva (Wisconsin) News, October 23, 1924, 4, referring to Pells Lake with “West Geneva,” Lake Geneva News, October 30, 1924, 9, referencing Pell Lake.

2. Julius Freudenthal was a noteworthy character in his own right. He was one of the principals in the Longfellow mine and became wealthy when it was sold. A casualty of the Panic of 1893, he was the subject of a lengthy article on the front page of the New York Times and in newspapers across the country when, in 1896, he avoided creditors by disappearing, leaving his son Ludwig exposed for some of his debt. “J. Freudenthal Missing,” New York Times, July 12, 1896, 1; “Business Troubles,” New York Times, July 15, 1896, 11.

3. Holtzheimer to Freudenthal, WCRD, Deeds, 174:79; Kull to Freudenthal, 174:80–81.

4. Kull to Freudenthal, WCRD, Deeds, date unreadable, 174:170; Reeves to Freudenthal, July 19, 1924, 174:276; Hibbard to Freudenthal, August, 14, 1924, 174:332.

5. Freudenthal to Smadbeck, WCRD, Deeds, May 2, 1924, 175: 413, 415, 418; June 16, 1924, 175:416; July 25 1924, 174:284; August 16, 1924, 174:383; September 20, 1924, 175:635; December 5, 1924, 176:319.

6. Lee E. Lawrence, “The Wisconsin Ice Trade,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 48, no. 4 (Summer 1965).

7. Consumers Company to Freudenthal, WCRD, Deeds, May 15, 1924, 175:319.

8. “Start Work to Enlarge Pell Lake,” Lake Geneva (Wisconsin) News Tribune, March 11, 1926, 1.

9. WCRD, Plats, Pell Lake Subdivision Section 1, July 16, 1924, 3:77; Section 2, July 16, 1924, 3:77A; Section 3, August, 5, 1924, 3:78; Section 4, August 23, 1924, 3:79; Section 5, September 2, 1924, 1:89; Section 6, September 29, 1924, 1:90A; Section 7, October 10, 1924, 2:11A; Section A, August 23, 1924, 3:78A; Section B, October 10, 1924, 2:11.

10. Sixty-Fifth Annual Report of the Chicago and North Western Railway Company, Year Ending December 31, 1924 (C and NW Railway Company, 1924), 14.

11. McHenry (Wisconsin) Plaindealer, April 9, 1925, 7; Display Ad, Chicago Evening Post, June 4, 1925, 5.

12. “Subdivision at Lake Como To Be Largest Yet,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, December 3, 1925, 1.

13. Twenty-four-hour electric service arrived at Pell Lake in 1929. “Areas Are Using More Electricity,” Oshkosh Daily Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), December 31, 1929, 18.

14. Appointment of U.S. Postmasters, 1832–1971, 92:458.

15. “Short Notes,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, July 5, 1928, 8.

16. Lake Geneva News Tribune, August 6, 1925, 1.

17. Lake Geneva News Tribune, November 19, 1925, 1.

18. Lake Geneva News Tribune, May 28, 1925, 7.

19. Pell Lake Property Owners Association, Wisconsin Department of Financial Institutions (WDFI), December 18, 1925, Entity ID 6P02082.

20. Hussey to Pell Lake Property Owners Association, WCRD, Deeds, January 7, 1926, 193:231.

21. Smadbeck to Jonap, WCRD, Deeds, February 23, 1927, 193:345.

22. Sitterle's Subdivision, WCRD, Plats, November 7, 1924, 2:13; Sitterle's Addition, August 13, 1925, Plats, 2:19.

23. Pell Lake Highlands, WCRD, Plats, June 12, 1925, 1:99.

24. “Kimball Sells Part of Farm at Pells Lake,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, April 9, 1925, 1.

25. Leon Sex was also responsible for resort developments at Lily Lake, Lakemoor, and Channel Lake, all in northern Illinois. None of his projects were tied to newspaper subscriptions.

26. Pell Lake Addition, WCRD, Plats, June 17, 1925, 8:29.

27. “Buy Site for Splendid Hotel at Pell Lake,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, March 18, 1926, 1; See also Robert Streit to The Public, WCRD, Farm Names, February 1, 1926, 1:89.

28. Display Ad, Chicago Evening Post, June 4, 1925, 5.

29. “Bloomfield,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, February 19, 1925, 2.

30. Pell Farm Annex, WCRD, Plats, September 29, 1925, 2:21A.

31. Motorists had to wait until August 12, 1928 for the last stretch of concrete paving, between McHenry and Richmond, Illinois, to be opened to traffic. “Short Route to Chicago Opened to Traffic Sunday,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, August 16, 1928, 1.

32. Conversation with Art Oster, August 25, 2019.

33. McHenry Plaindealer, June 11, 1925, 1, and April 9, 1925, 7.

34. “An Opportunity,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, April 9, 1925, 6.

35. “Business Men Report Good Season Despite Poor Weather,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, September 16, 1926, 1.

36. “Will Collect $175,000 For Taxes in City,” Lake Geneva News Tribune, January 14, 1926, 1.