The following is a list of annual and perennial vegetables with which I am reasonably familiar. Each item on the list is followed by a discussion of how and when these vegetables might need mulch.

While considering the suggestions made here, keep several things in mind: 1) the general mulching guidelines offered in the earlier chapters, 2) your own experience with a particular vegetable, 3) the climate in your area, and 4) the idiosyncrasies of your garden, such as the soil condition, drainage, the amount of sunlight, and the likelihood of certain pests. As always, I will try to resist telling you what to do and will leave you the burden of deciding whether and how and when to mulch what in your garden.

Just so this doesn’t sound like a total cop-out, let me say I think you will find lots of useful information here that you can adapt to your own situation.

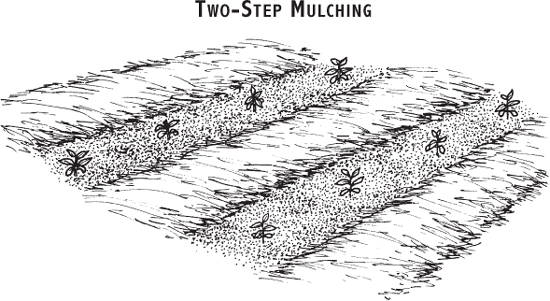

When seeds are first planted, mulch between rows.

When plants are established, move mulch closer to plants.

If you are just starting a new asparagus bed, mulching probably is not necessary until the second spring — although if you live in a cold place like Vermont or Minnesota, you will want to mulch for winter protection even in the first year. Hay, leaves, straw, old manure, and compost are just a few mulches that are excellent for winter protection of asparagus.

As you know, once a bed has established itself it will continue to produce asparagus for many years. In the spring, there is no need to remove winter mulch. The tips will come right up through the mulch whenever they are ready. Eight inches of hay mulch is not too much for asparagus. Its primary function is weed control, but it may have other fringe benefits.

To extend your asparagus season, divide your bed into two parts in the spring. Mulch half of the bed heavily with a fine material such as cocoa hulls, ground corncobs, chopped leaves, or leaf mold. Leave the other half unmulched until the shoots begin to break through the mulched half. Then mulch where you did not mulch before. Don’t worry about weed control with the temporarily unmulched bed — those first asparagus shoots will poke through early in the season, long before any weeds take hold. If you are prompt with your second application of mulch, you’ll still have excellent weed control. This technique should extend the asparagus season because the part of the bed that got its start without mulch will begin to bear one or two weeks earlier than the part that started out with mulch.

You can mulch beans about two or three weeks after planting. Mulching is especially beneficial to beans because it inhibits weed growth. The finer the mulch the better, if you like to plant beans in wide rows. Bean roots grow close to the surface, and any deep or extensive cultivation to halt weeds will result in undesirable root pruning of the beans themselves.

I have had trouble growing lima beans. I seem to get a germination rate no better than about 40 percent, and the yield is low, too. If you have luck with them where you are, your lima beans can be mulched with about 3 inches of a light organic material as soon as they are 4 inches high.

I do plant lots of soybeans, in wide rows or just broadcast. Left to their own devices they do just fine, so I don’t bother to mulch them, though I’m sure mulch would do no harm. Same with pole beans.

After planting some rows of beans in clear ground in my own garden one year, I poke-planted a wide row of green snap beans with my finger, through a walkway of hay books. I was a man of little faith, so the next day I went back to pull the books apart and loosen the hay a bit. The beans came up through the mulch just as quickly and, apparently, just as easily as those that had no mulch. They grew every bit as strong as, if not stronger than, their unmulched counterparts. In fact, even in extraordinarily wet seasons they look greener and healthier. Possibly this is because, thanks to the mulch, fewer nutrients were leached out of the soil by torrents of rain.

Beets like alkaline soil, so it is probably better not to mulch them with pine needles, oak and beech leaves, or peat moss exclusively. Use just about anything else. In fact, adding ground limestone or lime to the soil, or mixing it with the mulch, may be a good idea. Arthur Burrage says that “the use of mulch on the beet bed pays greater dividends than anywhere else on the garden.” Ideally, leaves or leaf compost should be spread on beet plots at least once a year and worked into the soil as fertilizer.

A light mulch of grass clippings can be put down right after planting beet seeds, to conserve moisture and prevent the sun from baking the soil hard. As soon as the sprouts appear, pull this mulch back a bit for a while, as beets are highly susceptible to damping off. As the growing season progresses, increase the thickness of the mulch by adding more layers of straw or hay, and some time after the rows have been thinned tuck it in close to the maturing plants. This procedure seems to work well for turnips and rutabagas, too.

Beets respond badly to boron shortages in the soil. Chopped kelp (seaweed), an excellent organic mulch, can correct this deficiency in a few weeks. Beets also thrive in humus-rich soil, and continuous mulching will contribute to this condition in your soil.

Broccoli can be mulched shortly after the plants have been moved out of the cold frame or greenhouse and set out in the garden. Any nonacidic organic mulch is fine — it will preserve moisture and discourage some insects. Late in the season, because broccoli is naturally frost resistant, the mulch can extend a plant’s productive time. Broccoli can stand a maximum of 4 to 6 inches of organic mulch.

Polyethylene works well with broccoli. If you use it, lay the plastic, cut holes, and transplant through the openings. A little fertilizer and lime ahead of time is probably in order.

After your transplants are well established, partially decomposed mulch can be tucked right up under the leaves around your cabbage plants. This may slow their growth somewhat, but they will grow tender, green, and succulent.

According to the Agricultural Experimental Station at the University of Connecticut, an aluminum foil mulch is especially suitable for cabbage. It discourages some disease-carrying aphids.

If you live in a climate that normally experiences mild winters, you might like to plant cabbage seed and cover the beds with a mulch in the late fall — in November or early December. Re-cover the bed with coarser mulch, such as twigs or evergreen boughs, as soon as the seedlings appear. In spring, when you uncover them, you will have some hardy babies for early transplanting.

Everyone seems to agree that cantaloupes and other melons need lots of moisture as well as heat, from the time they come up until they are fully grown. Advocates of plastic mulch feel they get an earlier and larger yield by using black polyethylene film. This, they say, is especially helpful when the spring is cool and dry. The film helps to warm the soil, eliminates weeds, and maintains a more constant supply of water to the roots.

A thick organic mulch is designed to do pretty much the same thing. Hay, grass clippings, buckwheat hulls, cocoa shells, and newspapers work fine. It probably is better to stay away from sawdust and leaves. The mulch should be in place before the fruit develops, since handling may damage the tender melons. Once the fruit is formed, it will be resting on a clean carpet of mulch and won’t be as prone to rot.

I like to see melon plants maintain contact with the soil because the runners themselves absorb moisture and nourishment from the ground. So I discourage the use of plastics or any organic mulch that the runners can not be tucked under easily. In fact, in a normal year I prefer no mulch at all at least until the fruit has started to form. Then, to keep the fruit clean, I carefully set the melons on top of tin cans. This also makes them sweeter — I don’t know why, exactly, but I think it might have something to do with the melons getting more uniform heat. A tin can mulch, you say? How could master mulcher Ted Flanagan have missed that one?

Mulch should be used very sparingly on carrots. When you sow carrots, you might want to spread a very thin mulch, say of grass clippings, over the beds to prevent the soil surface from forming a crust that the sprouting seeds can’t break through. Water this mulch if you like, but be careful that the tiny seeds don’t wash away. When the slender seedlings come up, be sure that the mulch does not interfere with them.

Ground coffee makes a good mulch for carrots, and you can apply it when you sow your seeds. Just mix a packet of seeds with 1 cup of fresh ground coffee and sow as usual. This light mulch seems to discourage wireworms.

Have you tried leaving your carrots in the ground during the early winter months to save storage space in the house? They can be kept there, covered with a heavy mulch to prevent freezing and thawing damage. Once dug up they won’t keep long, but many people prefer them to frozen or canned carrots from the supermarket.

Cauliflower can be mulched in much the same way as broccoli. Mulch right to the lower leaves shortly after transplanting, or lay plastic and plant through it.

The traditional way to “blanch” celery is with a soil mulch. Earth is pulled around the plants as they get higher, until finally, when the celery is fully grown, the celery rows are about 18 inches high and only the green tops are showing. As a cleaner alternative, try an organic mulch rather than soil to blanch your celery. Chopped leaves are best; whole leaves may dry out and blow away.

Celery that is protected with a deep mulch will produce crisp, tender hearts until Thanksgiving or later. Ideally the heavily mulched rows should be covered with sheet metal, plastic, or some other waterproof material to form a tent; with this protection, the ground stays dry and will not freeze too hard. You will be able to dig celery any time you want it, even in midwinter. Just shovel away some snow, remove the tent, and uncover as much celery as you want to eat. Celery that is protected this way keeps better than in a root cellar.

Some gardeners, like Ruth Stout, keep a permanent organic mulch on their corn patches. At planting time they just run a straight line with a string and push their corn seeds down through the mulch with their fingers. After the harvest, Mrs. Stout simply breaks the stalks over her foot and throws more hay over the old mulch.

Permanent mulchers argue that crows seem to be nonplussed by the heavy layer of mulch over corn. They often will pull out small corn plants nearly as fast as they show aboveground. If the corn has had a chance to get a good head start under mulch, the plants will yield disappointing results to the average crow, who is after those tender sprouted kernels below the plants.

Here in Vermont, where I worry about soil warmth until as late as early June, I plant corn in the bottom of a furrow and use no mulch for a while. I cover the seed with about an inch of soil — which doesn’t begin to fill the furrow — and stretch 12-inch chicken wire over the top of the furrow. The birds are unable to reach the planted kernels or the shoots through the wire. If you have no way to make a furrow (I just use a little furrower that attaches to the back of a rototiller), bend some 24-inch chicken wire down the middle to make an inverted V and form a tent over your row of corn. Be sure to close off the ends, or the birds will get in there and saunter down each row, picking kernels of corn seed out of the ground as they go. Remove the chicken wire tents once plants are 3 inches tall.

According to the old maxim, corn should be “knee high by the Fourth of July.” At just about this point, when the corn is “tall enough to shade the ground,” it’s time to mulch your corn. The stalks have been spaced or thinned carefully so they can be mulched without damage. The wire, of course, long since has been taken up. Use any mulch that will preserve moisture and give the corn an extra boost by adding nutrients to the soil.

Chopped leaves, leaf mold, straw, and old hay are good for mulching cucumbers. Mulch somehow seems to keep cucumber beetles away. It can be put around the plants when they are about 3 inches high and before the vines really start to extend. Cucumbers, of course, require much moisture, which the mulch will help to retain. Some organic mulches, as you already know, will invite some slugs, snails, diseases, and insects other than the cucumber beetle to your cukes. To be on the safe side, keep the mulch 3 or 4 inches away from the main plant.

Eggplant needs all the warmth it can get. Don’t mulch it until after the ground has really had a chance to warm up. Also, avoid disturbing the earth immediately around eggplant. Once the soil is warm enough, mulch will smother most weeds before they grow big enough to be pulled.

The roots of these finicky plants prefer to grow and feed in the top 2 inches of soil. If there is too little moisture there, the leaves turn yellow, become spotted, and drop off; if there is too much, the plant will not bear fruit. Mulch can help to keep a uniform supply of moisture there.

Eggplant is also apt to attract flea beetles. Aluminum, laid temporarily on top of other mulch, has been known to thwart these insects.

Garlic can be mulched when the plants are 6 to 8 inches high. Use a fine mulch like hulls, grass clippings, or chopped leaves. For more advice, see the Onions entry.

Kale is an incredibly hardy vegetable. It can be grown nearly any time of year. A fall or winter crop may be left in the field, covered lightly with something like hay, pea or cranberry vines, or straw. Later in the winter remove the snow (one of the mulches kale seems to like best, by the way) and cut the leaves as you want them. Kale will sometimes keep this way all winter, if it doesn’t get smothered by ice after a thaw.

Leeks and scallions can be mulched lightly with anything from straw to wood shavings. Just be sure that the mulch does not interfere with the very young seedlings. For more advice, see the Onions entry.

Leaf lettuce does well in semishade and in humus-rich soil. A very coarse mulch such as twigs, rye straw, or even pine boughs can be used in the seedbed. As the leaves grow, move the mulch right up underneath them. This does four things: It holds the soil moisture, keeps the leaves from being splashed with mud, prevents rot, and maintains the cool root run that many plants — especially cold-season vegetables like this — require for optimum production.

You can apply as much as 3 inches of mulch as soon as head lettuce is 3 or 4 inches high and has started to send out its leaves. According to Arthur Burrage, this helps to ensure good plant growth. Every head should mature properly this way, Burrage says: “It has always been a pleasure to look at the lettuce bed. There are rows of perfect heads resting on a light brown carpet of delightful appearance.”

Mulching helps onions. Almost everyone seems to agree on that. Even local folks who hesitate to mulch many things because they understand Vermont’s fickle climate will remark, “You can’t kill an onion.” Onions can and should be mulched during long hot spells. Chopped leaves can be sprinkled among the green shoots even if they are 2 or 3 inches high. Mulched onions will grow slowly and be more succulent than onions grown without mulch. A little more mulch can be added as the tops develop.

Ruth Stout says, “Onion sets may be just scattered around on last year’s mulch, then covered with a few inches of loose hay; by this method you can ‘plant’ a pound of them in a few minutes, and you may do it, if you like, before the ground thaws.”

I have planted onion sets several different ways myself:

• Planted in bare ground and left alone

• Planted in bare ground and mulched with finely chopped leaves when the plants are 4 to 6 inches high (this looks most attractive)

• Thrown under about 6 inches of hay mulch

I’ve noticed that the growth of the onions in bare ground tends to be very slow. And it almost seems that those mulched with the chopped leaves stop growing entirely. But the ones under hay have done well, growing large bottoms. Explain that one to me if you can.

Arthur Burrage uses a slightly modified approach. He puts down 2 to 4 inches of mulch when the onion tops are about 6 inches high. Burrage writes:

“For this mulch we use the remnants of what mulch was used in the bean, corn, and pea area of the previous year. We find that the remnants are broken down into smaller pieces and are easier to handle in rows planted close together than something like fresh straw. The few weeds that grow are easily pulled and the beds stay neat looking all summer. Our experience has been that our troubles, at least as far as onions are concerned, are over for the season. Nothing is left to do except to pick them.”

In places where winter is not as harsh as in the north, parsley can be protected by mulch throughout the winter. It can be planted in cold frames in August — or even later — covered with hay, left in the frames all winter, and transplanted to the garden in the early spring. Parsley is susceptible to crown rot, so summer mulches should be kept 5 to 6 inches away from the plant.

Parsnips do not grow well in tight, compacted soil: Instead of growing one straight root, they divide into three or four, which makes the root worthless. Mulching can help here by preventing compaction. But parsnips prefer a soil with a pH of about 6.5, so don’t use an acidic mulch. Like beets, parsnips will suffer if there is a boron deficiency in your soil. Seaweed has traces of boron and is often recommended for winter protection. Try some on your parsnips.

Most gardeners can eat parsnips from their gardens all winter if they are heaped high with leaves or some other protective mulch as cold weather moves in. They store very well. Don’t use them until after the first heavy frost; they won’t have reached their peak of quality until then anyway. Most folks think they are best in November and December. Will they survive –30°F? I keep forgetting to ask my mountaintop friend how his fared.

It is easy to overdo mulching peas in a cool climate like ours. The soil around peas does need to be cool and damp. In dry soil they will not germinate well, and a large percentage of the seeds will be lost. In late spring around here, I usually don’t have any trouble meeting either of these conditions without using mulch.

To grow peas in much warmer places, or to grow pea varieties like Wando later in the summer, mulch with a thin layer of grass clippings, straw, or hay when the seeds are sown. (I broadcast peas in some places and then bury them just under the surface with the rototiller.) As the plants get started, you can increase the mulch to insulate the soil from the atmosphere and the hot sun. This way you can almost assure yourself of a cool, moist root run.

One June, just as I was finishing planting my own peas in the traditional way (in rows without mulch), my wife called me to lunch. I still had a large fistful of seeds in my hand. Indolent fellow that I am (also very hungry, and a little curious, too, if the truth be known), I decided to throw the seeds away instead of putting them carefully back in the bag. With a furtive, sweeping gesture I quickly tossed the evidence of my own wastefulness under the rug of very heavy hay mulch. To my surprise, even though the seeds actually were never planted in the soil, the plants came up en masse and looked healthy and green.

The last time you pick your peas each season, pull up the whole vine before you remove the pods. This should help save your back. The vines should be stacked and saved, too. Chopped or whole, they are a nitrogen-rich mulch that can be used anywhere on the garden, except on other peas.

The growing habits of sweet peppers are very much like those of tomatoes. I often plant these two at the same time as companion plants. Early plants respond well to a black paper mulch. This will collect the heat of the day and help maintain a warm soil temperature for a while into the night. Later the paper mulch can be taken off and replaced with an organic mulch, or not replaced at all.

I have learned that pepper plants grown under hay mulch may be stunted and slow to mature. On the other hand, my own pepper plants, which are surrounded with dark, chopped leaf mold mixed with alfalfa meal, are quite a bit ahead of some peppers in other gardens. Peppers and dark-colored mulches seem to go well together.

Potatoes, if you use mulch, don’t even need to be planted! As Ruth Stout says, “Many people have discovered that they can lay seed potatoes on last year’s mulch, or on the ground or even on sod, cover them with about a foot of loose hay, and later simply pull back the mulch and pick up the new potatoes.”

This oversimplification may appear to some as another unfortunate Stoutism, but she is correct in saying that you can grow potatoes “under mulch, in mulch, on top of mulch — almost any way in fact — and get satisfactory results.” You can harvest early potatoes from their thick mulch bed and then replace the covering.

Deep mulch also seems to thwart the potato bug, whose larva winters in the soil. Apparently these fellows are reluctant to climb up the potato stem though the thick hay.

Pumpkins profit from freshly cut hay, composted leaves, straw, and cow manure. Mulch around each hill. As the crop starts to mature, use any coarse mulch that keeps the fruit off the ground.

Mulch is not recommended for quick-growing plants like radishes, as there usually is not enough time for mulch to do them any good. For the most part, plants that prefer cool, moist soil respond better to mulches than those that revel in hot sun and dry soil.

Thick stalks of rhubarb result from continuous heavy feeding. Spread a thick mulch of strawy manure over the bed after the ground freezes in the winter. In the spring, rake the residue aside to allow the ground to warm and the plants to sprout. Then draw the residue, together with a thick new blanket of straw mulch, up around the plants. Hay, leaves, or sawdust also makes excellent mulch for rhubarb.

Mulching spinach and similar vegetables seems like a waste of time to me since they’re such short-season crops, but some say that spinach can be mulched with grass clippings, chopped hay, or ground corncobs and be better for it. Since spinach does not do well in acidic soil, avoid peat moss, oak and beech leaves, pine needles, and sawdust. In any case, I don’t advise putting down a summer mulch until the leaves have had a chance to make a good growth.

Squash can use an extraspecial dose of mulch, especially during hot, dry spells. The mulch, whether it be rotted sawdust, compost, hay, or just leaves, can be as deep as 4 inches. Leave the center open so that some heat can get to the middle of the plant. The mulch over the rest of the patch will preserve moisture and discourage some bugs. I probably don’t need to remind you how much space is taken up by squash. Be sure that you have plenty of mulch before you commit yourself. Don’t bother mulching winter squash.

Sweet potatoes are ravenous feeders and are happiest in plenty of moisture. Compost is an ideal mulch for just these reasons. Old leaves and grass clippings make a good organic side-dressing, as do the old standbys, hay and straw. If you plant sweet potatoes in hills, mulch and fertilize them well, and allow them lots of room to develop.

Some vegetables such as tomatoes (as well as peppers and corn) need thoroughly warmed soil to encourage ideal growth. A mulch that is applied too early in the spring, before soil temperatures have had a chance to climb a little in frost zone areas, will slow such crops. Generally, in colder climates, tomatoes need less mulch. Dark-colored mulches can help seal in heat and moisture.

Black and red plastic mulches, used in commercial cultivation, are increasingly popular among gardeners who want earlier crops and more fruits and vegetables. Black and red plastic mulches warm the soil so you can start planting earlier and continue harvesting longer. They also conserve moisture and control weeds. They are best applied either before or soon after plants are in the ground.

Red plastic mulch is Selective Reflecting Mulch (SRM-Red), a new material that performs like black mulch. It’s more expensive than the black, but USDA tests show it increases tomato production by about 40 percent; it also reduces nematodes (see page 60).

A good time to mulch with other materials is right after the flowers appear. Blossom-end rot can be caused by a variable moisture supply. Mulch keeps a more consistent supply of moisture around the roots of the plants. I have used chopped alfalfa hay, chopped pea vines, chopped leaves, and straw. Early plantings have been mulched with felt paper to keep the soil warm. If you have lots of mulch and few sticks to use as tomato stakes, forget about staking. Let your plants run around freely over the mulch and let the fruit ripen there.

Here is still another plant that should not be mulched until the soil is really warm. How many gallons of water do you suppose there are in one large watermelon? Obviously the melons demand all kinds of soil moisture. The best time to apply mulch is when the soil has been dampened thoroughly. Up to 6 inches of mulch can be spread over the entire patch, if you like, to prevent rot and to keep the fruit dirt free.