7

Never Mind the Bollocks

Shepard Fairey’s Fight for Appropriation, Fair Use, and Free Culture

Evelyn McDonnell

Every sk8ter boi with a Clash album and a can of spray paint wants to change the world. In late January 2008, Shepard Fairey may have done just that. He decided to create something he had never, in some twenty years of producing stickers, murals, T-shirts, prints, stencils, tags, and canvases, made before: a poster endorsing a popular political candidate.

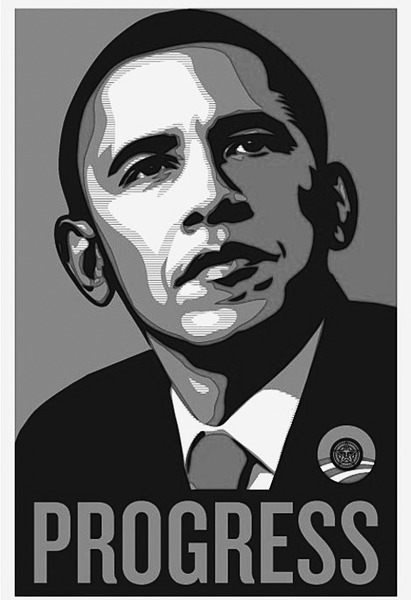

Since Barack Obama was not exactly available to pose for some grassroots graphic artist, Fairey found a photo of the senator online. With a couple mouse clicks, he copied a shot taken by Mannie Garcia in 2006 for the Associated Press (AP). Then he turned a news photo into a propagandist art statement. Fairey replaced the natural tones of the photo with the strong lines and bold colors of Russian Constructivist art. He added oversized cartoon hatch-mark shadings in the style of Roy Lichtenstein. Across the bottom, he wrote: “Progress.” In later iterations, he changed “Progress” to “Hope.”

Fairey’s Obama “Hope” poster is the most iconic, widely seen work of art in recent history. Its bold, dignified profile succinctly communicated both patriotism and change better than any other single image in a mediagenic campaign. “Hope” captured and helped enable a historic moment. And it got its maker, a longtime street artist, prankster, and political activist who was already one of the most widely known culture jammers, into a heap of trouble—a serious legal jam. In 2009, Fairey and the AP sued each other over the artist’s use of Garcia’s photo. “Hope” may not have merely helped the United States elect its first African American president; it also became a test case for and raised public awareness of one of the most important issues of the digital age: intellectual property.

Fairey’s lawsuits with the Associated Press (which were settled out of court in January 2011 in a confidential agreement) highlighted the changing rules of intellectual property. This culture jam provided a case study in what media studies scholars Henry Jenkins et al. (2006) have described as the New Media Literacy of appropriation—a cultural form explicitly borrowing from another as a means of commenting and paying tribute. In 2006, the MacArthur Foundation funded a $50 million study of digital culture and learning. In a 2006 white paper written under funding from that study, Jenkins et al. identify the skills that are enabled by new media and explore how they might be implemented in classrooms. Appropriation is one of these main skills. “The digital remixing of media content makes visible the degree to which all cultural expression builds on what has come before,” the authors write. “Appropriation is understood here as a process by which students learn by taking culture apart and putting it back together” (32).

The disruption/eruption of an underground artist into mainstream and commercial ideology is also an example of what Jenkins (2006) calls “convergence culture,” which is marked by “a cultural shift as consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections among dispersed media content” (3). The story of the “Hope” poster is the story of divergence as well—of increasingly closed copyright law deviating from increasingly open-sourced public practice. In this case, the law and mainstream media aligned themselves against market capitalism and anarchist street culture.

A close analysis of the Fairey-AP battle—or what could be called the case against “Hope”—provides key insights into the status of appropriation, fair use, free culture, and engaged citizenry during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The case illustrates what can happen to culture jammers when they fly too close to the sun—or the global media spotlight. The battle may have been a strategic turning point in what Harvard professor Lawrence Lessig (2005) has called the war against free culture. “There is no good reason for the current struggle around Internet technologies to continue” he writes. “There will be great harm to our tradition and culture if it is allowed to continue unchecked. We must come to understand the source of this war. We must resolve it soon” (11). By studying Fairey’s tactics of appropriation, we take another step toward understanding that war. Lessig may be optimistic in saying that understanding can lead to resolution, but it can certainly inform further activism and creativity.

The case for “Hope” indicates that the aesthetics of culture jamming—of street artists, punk, and Pop Art—are no longer confined to outsider practices. Fairey’s creation didn’t just go “all-city,” the goal of 1970s graffiti artists; it went all-world. As communications scholar Sarah Banet-Weiser (2012) has said of Fairey’s success, “The cultural capital of the street is now invaluable in the world of mainstream branding” (122). What does it mean when a once-subversive art style becomes the defining propaganda tool of the winning presidential campaign of one of the world’s most powerful nations? A skateboard punk from middle America helped the first black American president get elected, and got a shitload of legal and PR trouble for his efforts.

Anarchy in the Public Domain

Fairey’s use of Garcia’s image, and the entire New Media Literacy (NML) conception of appropriation, have historical precedents in the cultural traditions in which the artist was steeped: punk, collage, street art, and Pop Art. Frank Shepard Fairey grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. He discovered punk rock and skateboard subculture as a teenager. “The Sex Pistols changed my life,” he said in an interview with this writer in November 2009. “That was the gateway band for me.”1

The Sex Pistols, the English band that sang about “Anarchy in the UK” in a music driven by over-amped guitars and Johnny Rotten’s sarcastic snarl, were Fairey’s gateway out of conservative Southern culture and into a global youth subculture characterized by rebellion against mainstream and corporate values. “There’s not a lot of progressive culture there,” he has said of his hometown. “I got into the skateboarding and punk life. That opened my eyes to political and social critique: How art could work with things that are political” (Fairey 2009a).

The cover of the band’s 1977 debut album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, was designed by English artist Jamie Reid. Reid did for punk music what Fairey would later do for the Obama campaign, providing a distinctive iconography, in this case made out of cut-up, xeroxed images and ransom-note-style lettering. In one famous piece, he put a safety pin through the lip of a reproduction of a photograph of Queen Elizabeth II, providing a visual complement to the Pistols’ song “God Save the Queen” (figure 7.1). Reid’s irreverent mash-ups were clearly instances of the public defacing of hegemonic corporate images, and subsequent punk bands and culture jammers such as Negativland were undoubtedly influenced by his collages. Like the Pistols’ music, Reid’s art provoked the establishment and stirred up a youth cultural movement—punk—that years later would reach a young Fairey in the American South. Still, as far as I can tell, Reid was not sued by royal photographer Peter Grugeon for his appropriation.2

There was a purpose to this playfulness. Do-it-yourself—the notion that culture should actively be in the creative hands of the people, not just something produced by corporations and consumed by a passive audience—was a guiding ethos of punk. In reaction to the showy musicianship of art-rock, such bands as the Clash advocated the notion that music be simplified and demystified, so that anyone could play it. In a similar vein, cut-up art like Reid’s is a way to claim images that permeate public spaces (the queen’s face was omnipresent in 1977 England, the year of the Silver Jubilee), assert individual expression over them (the safety pin), and make them public domain (Reid’s image was stickered around town). Through media bricolage, Reid and other punk ’zine creators asserted individuals’ rights to exploit and manipulate commercial imagery, since commercial imagery exploits and manipulates the public. They were appropriating, creating visual remixes and mash-ups, culture jamming—long before those were digital-culture buzzwords.

Fairey was also inspired by another musical subculture of the 1970s: hip-hop. Graffiti is considered one of the four main elements of hip-hop—the other three being DJing, breakdancing (or B-boying), and rapping (Chang 2005). Like punk cut-up art, graffiti is also an assertion of the individual’s right to self-expression in the public domain, with the legal concept of public domain meant quite tangibly—on subway cars and abandoned buildings. The art of spray-painting tags (aliases of graffiti artists) and street murals exploded during New York’s fiscal crisis of the 1970s, as colorful balloon letters and stylized characters proliferated on subway cars and abandoned buildings. Such practitioners as Futura 2000, Rammellzee, Lady Pink, Revs, Cost, and Claw became famous for going “all-city” (Shapiro 2005). Street artists Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat also crossed over into the world of fine art, becoming celebrities of the Downtown scene of the 1980s.

Figure 7.1. “God Save the Queen.” Image by Jamie Reid, courtesy of John Marchant Gallery UK. Copyright Sex Pistols Residuals.

Art student Fairey witnessed this work all around him on a 1989 visit to New York. “I saw graffiti in risky places that gave me new respect for the dedication of the writers,” he writes in Obey: Supply and Demand: The Art of Shepard Fairey. “Stickers and tags coated every surface in New York City. I left the city inspired” (Fairey et al. 2009, 18).

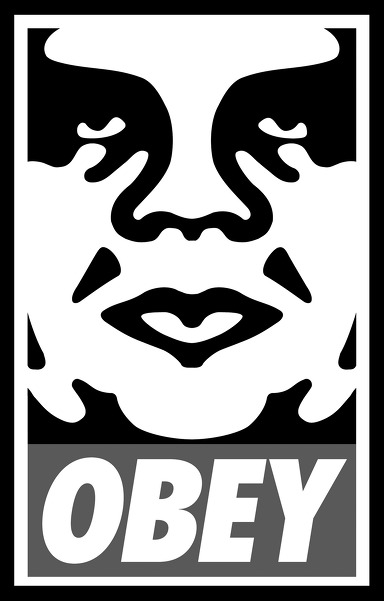

The graphic creation that first made Fairey famous in underground circles was a punk sticker, in the spirit of “God Save the Queen.” While he was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1989, Fairey made a stencil of plus-sized wrestler and actor Andre the Giant and added the words “Andre the Giant Has a Posse,” plus his height and weight. He plastered the stickers around Providence. One day a local weekly, the Nice Paper, took note. Soon, the Andre campaign spread to nearby Boston and New York. Fairey sent stickers to friends who put them up wherever they lived. He advertised in punk magazines and sold the stickers by mail order for five cents each. Within seven years, he had printed and distributed a million of these Andre stickers. Fairey also made posters and stencils. André René Roussimoff died in 1993, but he and his make-believe posse were ubiquitous on urban street lamps and walls for years afterward (Fairey et al. 2009).

In the 1990s, Fairey altered the image of Andre due to concerns over intellectual property (Whittaker 2008). The face morphed into a bold graphic abstraction, and the caption read simply “Obey” or “Giant.” The forced change actually enabled Fairey’s art to become more sophisticated and distinctive—in fact, Fairey has written that he initiated the shift because he had become fascinated with the agit-prop art of Russian Constructivism (Fairey et al. 2009, 35). The style that was to become world-famous with “Hope” was already apparent in the “Obey Giant” series of 1995.

Appropriation was not only a tool of punk and street art. Reclamation and transformation of commercial or public images also came to be accepted in the highbrow art world of museums and galleries in the twentieth century. With his famous urinal sculpture of 1917, Marcel Duchamp, along with the Dadaists, was at the vanguard of conceptual installation art. Robert Rauschenberg’s work of the 1950s mixed found objects and images. In the 1960s, Andy Warhol made brightly colored silkscreens of Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe, and Elvis Presley. In the 1970s Richard Prince rephotographed commercial shots of Marlboro Men and Brooke Shields. As with Reid, these artists prefigured the ideas and even methods of such future culture jammers as Adbusters.

Such appropriative art has been both highly successful—a Prince work sold for $1.2 million in 2005—and controversial—he was sued over the Shields shot and reportedly settled out of court for a small fee (Kennedy 2007). Still, appropriation has become widely accepted as an artistic practice. In 2009, Miami’s Rubell Family Collection launched an exhibit called “Beg Borrow and Steal” that featured seventy-four artists, including Mike Kelley, Rashid Johnson, David Hammons, Paul McCarthy, and Sherrie Levine, all engaged in various forms of mimicry. “Artists are acting as cultural curators; through their work they’re recurating history and recontextualizing it,” said Jason Rubell, one of the exhibit’s curators. “They’re appropriating and reassessing imagery that came before” (pers. comm.).

In the same way that Reid and the punks utilized it, appropriation by fine artists may be an effective tool against mass media bombardment, a way of reclaiming public space from corporate control. “There’s an enormous difference between imitation and appropriation,” said Rene Morales, a curator at the Miami Art Museum, which co-produced an installation by Fairey in December 2009. “Appropriation is a creative act; it’s become one of the most effective ways to make art in a media-saturated word” (pers. comm.).

The works of Rauschenberg, Warhol, Prince, and others influenced Fairey. In a sense, they pioneered a core technique of culture jammers, taking ubiquitous commercial icons and repurposing them for their own artistic purposes. “My favorite artists are people like Jamie Reid and Rauschenberg and Warhol, who incorporated existing art work in their work but did it in a way that made something that wasn’t very special incredibly special,” Fairey said.

To those who decry lack of originality in Fairey’s work, the artist agrees. “The idea of originality is pretty ridiculous. It’s virtually impossible to be original. Language is based on reference. To me as a visual artist, I use reference in my work all the time, both images that have a specific connotation and styles that have a specific connotation.” For instance, in the “Obey Giant” artworks, Fairey wrote “Obey” in red capital letters. This was his homage to 1990s art star Barbara Kruger, whom he calls “the most political, outspoken artist” of that time. “I liked her work and I thought that if I used that style, people were going to wonder what I was trying to say. I think she understood she should be flattered.”

Russian Constructivism, Reid, Warhol, Kruger: The artistic influences on Fairey’s work are clear. He is as unapologetically derivative in his image choices as in his methods. He doesn’t draw or paint the central figures of his pieces. He uses images created by others, either by photographers with whom he is collaborating or images he finds online, or at agencies that sell stock photos, or that are already well known (such as his series on famous musicians). “There’s no shortage of images,” he said with a twinkle of ironic mischief. “It’s just that there’s an abundance of lawyers as well.”

Whereas Prince simply rephotographed some of his most famous pieces, without modification, Fairey alters, sometimes radically, the works he appropriates, with exacto knives, computer tools, or by hand illustrating them. He defends his methods philosophically:

I’m biased to my own idea that images are abundant but making them special is what’s important. Looking at how to distill what will make something iconic is what I think my skill is. There’s some people who have great brush strokes and others who come up with cool color combinations. This is my skill, and whether the law said it’s okay or not, it’s what my skill is. . . . There’s a huge debate with new technology about what constitutes legitimate art. Does it have to be done with a paintbrush or with your hands? I enjoy illustrating with my hands. But really, your eyes make the art. You make the decisions by looking at things and transferring what you want to do in any number of ways, whether it’s with your hands or digitally or with photography. The end result is what’s important. You may be Jeff Koons and have fabricators build it and never touch it. That to me is what art’s about: Whether that end result, however you got there, affects people and said what you wanted to say.

Computers help artists like Fairey turn creation into a hands-off, eyes-on experience. Digital technology is radically changing the way the arts are made, transmitted, communicated, marketed, taught, learned, and controlled. The art of cutting, pasting, and remixing—whether in Garage Band, word-processing software, Photoshop, iMovie—is now intrinsic to digital culture’s transformative power. “The Internet has unleashed an extraordinary possibility for many to participate in the process of building and cultivating a culture that reaches far beyond local boundaries,” Lessig (2004) writes. “That power has changed the marketplace for making and cultivating culture generally, and that change in turn threatens established content industries” (9).

Jenkins and his collaborators recognized the importance of remixing for youth accustomed to digital tools and named it the New Media Literacy “appropriation” in their 2006 MacArthur Foundation report. “Appropriation may be understood as a process that involves both analysis and commentary,” they wrote. “Sampling intelligently from the existing cultural reservoir requires a close analysis of the existing structures and uses of this material; remixing requires an appreciation of emerging structures and latent potential meanings” (Jenkins et al. 2006, 33).

Fairey’s “Hope” poster is a definitive example of appropriation. Fairey was engaged in the essential appropriative processes of analysis and commentary when he remixed Garcia’s photo, an image grabbed “from the existing cultural reservoir” (in this case, the Associated Press). Saturating the black and white pixels with bold primary colors, he verbalized latent meanings: “Progress,” “Hope.”

The Clampdown

Appropriation may be recognized and respected by artists, punks, rappers, scholars, and educational foundations. But it is also at the center of a legal battleground. As an artist who was sued for copyright infringement, Fairey followed in the footsteps of Richard Prince and rappers 2 Live Crew. But he was the first artist to engage in litigation with a news giant during a time when Internet communication technologies had fundamentally shaken traditional media roles and economic models.

Intellectual property (IP) law is complicated, to say the least. As Jessica Litman (2006) quips, “Copyright law questions can make delightful cocktail-party small talk, but copyright law answers tend to make eyes glaze over everywhere” (13). Essentially, the law in America historically seeks a balance between the need to guarantee creators and inventors a financial incentive to create and invent and the right of the public at large to participate in the free exchange of ideas. The overall goal, as stated in the Constitution, is “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.” Intrinsic to that progress and free expression, certain uses of copyrighted material are protected as fair use. Legal scholar Paul Goldstein (2003) explains that “the Copyright Act allows the copying of copyrighted material if it is done for a salutary purpose—news reporting, teaching, criticism are examples—and if other statutory factors weigh in its favor” (15).

Determining what use is fair has often been settled by litigation and involved unlikely defendants. The Miami bass group 2 Live Crew took their fight for the right to appropriate all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1990 music publishers Acuff-Rose sued the salacious rappers for sampling the Roy Orbison song “Oh, Pretty Woman,” to which they owned the rights. The lawyers for 2 Live Crew defended the use as an act of parody and therefore an example of fair use. The Supreme Court agreed: “The goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works,” wrote Justice David Souter in a decision that would later have ramifications for Fairey (quoted in Goldstein 2003, 27). But other artists who have used samples have not successfully claimed the parody fair use defense and lost their cases. Since the rapper Biz Markie was forced to remove a track from his 1991 album I Need a Haircut, musicians have repeatedly been sued over royalties. When it comes to digital culture and pop music, jurists and legislators tend to side with multimedia corporations in cases that are changing the rules of intellectual property. The courts shut down music distribution systems Napster and MP3.com in 2001 and issued restrictive, expensive licensing rules that effectively silenced Internet radio for a time. Lessig (2004), the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and others have documented and contested this erosion of free culture. “In the middle of the chaos that the Internet has created, an extraordinary land grab is occurring,” Lessig writes. “The law and technology are being shifted to give content holders a kind of control over our culture that they have never had before. And in this extremism, many an opportunity for new innovation and new creativity will be lost (181).

Litman (2006) refers to this land grab by the vested interests of media conglomerates as the “Copyright Wars.” “If current trends continue unabated,” she writes, “we are likely to experience a violent collision between our expectations of freedom of expression and the enhanced copyright law” (14). It was into this legal battleground that Shepard Fairey strode with seemingly noble intentions, but headed for a showdown.

“Hope”

Since the early days of the “Obey” stickers, Fairey’s work had become increasingly political. Influenced by punk and Constructivism, he unabashedly referred to his work as propaganda. As his political convictions deepened, he went from being a culture jammer, poking holes in consumerist culture, to a political commentator and activist, bringing culture jamming aesthetics to electoral campaigns. During the 2004 election Fairey made a series of posters attacking George W. Bush and the war on Iraq; he also created posters for the presidential campaign of consumer-rights advocate Ralph Nader.

For the 2008 election, he decided to take a different tack:

I’d spent a lot of time criticizing the Bush administration, the war in Iraq—things I unfortunately didn’t have enough power to prevent but I could at least try to dissuade people from making the same mistakes again. A lot of people really respond to negative images because venting is cathartic. I had started to think about why my anti-Bush images and other people’s anti-Bush images had not kept Bush from being reelected in 2004. Maybe it makes more sense to support rather than oppose. And I looked at Obama as the unique opportunity to endorse a mainstream candidate. . . . The ceiling to a lot of the rebel culture and the real activism and quasi-activism was these people are glad to talk but don’t do anything to engage in this process enough to make an actual difference. I said I’m going to engage in this process. One of the most compelling things was having a two-and-a-half-year old and being about to have another baby. And thinking it’s far more important to have them not growing up under McCain than for me to maintain my brand as anti-mainstream.

So in January 2008, as Obama was emerging as a front runner in the Democratic race but before the Super Tuesday primaries, Fairey made the “Progress” poster.

I made the Obama poster just like I made any other poster. The week before it was a ballot box with a speaker on the front saying, “Engage in democracy, vote.” To me it was just another political image. . . . I had no idea it was going to be such a hit.

Fairey intentionally created a piece that reached beyond the grassroots cultures that had been his comfortable home.

I did purposefully try to make it something that I thought could cross over that would have enough appeal to my fan base to stylistically work for them and also not be quite as edgy or threatening. And not in any way to be ironic, to be sincere. And patriotic. My feeling was that all my friends are already going to vote for Obama. The person that hopefully this image will appeal to is the person who’s on the fence. It needs to be something that’s nonthreatening. Something—this sounds really corny—but something that would maybe be hopeful and inspirational.

Fairey originally did with the “Progress” poster what he had done with its predecessors: He made a limited print run of three to four hundred that he sold, then used the money to make more posters to distribute for free. Oprah Winfrey and Michelle Obama held a rally at the University of California, Los Angeles, at which he gave away ten thousand copies. In the meantime, Fairey had been in contact with people inside the Obama campaign, who liked the artwork but preferred it carry a different textual message. “Hope” and “Change” were the keywords they were trying to promote, Fairey said. So he made a new version for the campaign.

“I chose ‘hope’ because I think a lot of people are complacent and apathetic because they feel powerless,” he said. “The first thing to motivate people to action is a level of optimism that their actions will make a difference. Hope is important because so many people feel hopeless.”

The rest, as the saying goes, is history. Fairey’s artful yet simple, dramatically chromatic message struck a chord. He made the “Hope” poster available as a free download on his website, with the condition that any proceeds from sales go to the Obama campaign. Soon, “Hope” was everywhere, a powerful illustration of the way in which the Internet enables networked communication. Fairey received a letter of thanks from the presidential candidate on February 22, 2008, that said in part: “The political messages involved in your work have encouraged Americans to believe they can help change the status-quo” (quoted in Fairey et al. 2009, 273). On January 17, 2009, the Smithsonian unveiled a mural based on “Hope.”

For the art’s maker, the experience, at that point, was a positive lesson in civic engagement. Fairey said:

I’m proud of the image. I put all the money from it back into making more posters, giving money to the campaign, organizing the Manifest Hope art shows. It was all related to supporting Obama. There was no goal for personal gain. Of course publicity wise, it was great for me. I’m very fortunate that I’m doing that well in my career that I can dedicate that much time to supporting a candidate and not have to have an ulterior motive, like the ambassadorship to Puerto Rico. It was something that was really heartfelt and I’m really glad Obama’s president.

Backlash

“Hope” catapulted the already successful Fairey to a level of notoriety enjoyed by few contemporary artists. Needless to say, he had backed the right horse: He drew the official 2009 inaugural poster for Obama. He was the subject of numerous articles and was commissioned by Levi’s to design a line of jeans. He was hired to draw covers of Time and Rolling Stone. The style of the “Hope” poster was itself widely appropriated and parodied (more on that later). But with fame comes friction.

In February 2009, the prestigious Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston debuted an exhibition of Fairey’s work. The show had been scheduled before “Hope,” the artist said. But of course, the opening got a lot more attention as a result of Fairey’s heightened profile. Not all of this attention was positive, though. The night of the opening, Fairey was arrested by Boston police for acts of vandalism related to Fairey’s public admission that he had performed numerous acts of street art during his lifetime, including when he lived in nearby Providence. “The Boston arrest was a lot of different things converging,” he said. “I made the mistake of being very candid about my practice as a street artist. The Boston police said that’s an affront to the Commonwealth.”

Fairey had been arrested for vandalism before. But he had never engaged in legal battle with a large corporation for copyright infringement. Actually, it was the artist who, after several months of communications with AP lawyers, threw down the formal legal gauntlet: On February 9, 2009, with the Stanford University Fair Use Project as his legal team, he filed suit in US District Court in New York to vindicate his rights to the image of Obama. The AP, saying in a statement that it was disappointed that Fairey had broken off negotiations over the Garcia image, filed a countersuit. What the AP called “negotiations,” Fairey had seen as legal threats.

Fairey’s case centered on fair use. The suit argued that Fairey “altered the original with new meaning, new expression, and new messages,” and did not create the art for commercial gain; that he “used only a portion of the Garcia Photograph, and the portion he used was reasonable in light of Fairey’s expressive purpose”; and that his use “imposed no significant or cognizable harm to the value of the Garcia Photograph or any market for it or any derivatives; on the contrary, Fairey has enhanced the value of the Garcia photograph beyond measure.”3

In response, the AP argued that Fairey’s use of the photograph was substantial and not transformative: “The Infringing Works copy all the distinctive and unequivocally recognizable elements of the Obama Photo in their entire detail, retaining the heart and essence of The AP’s photo, including but not limited to its patriotic theme.”4 It also charged that as of September 2008, Fairey had made $400,000 off the image. In a statement available on the AP website, spokesman Paul Colford said the organization was itself acting in defense of creators: “AP believes it is crucial to protect photographers, who are creators and artists. Their work should not be misappropriated by others.”5

In October 2009, there was a significant, but troubling, development in the case. Fairey admitted that he had misstated which Garcia photo he had originally used for the poster. Instead of a photo in which Obama was shown next to actor George Clooney, he used a photo of Obama’s face alone. He also admitted that he had altered evidence to cover up his misstatement. Fairey’s lawyers resigned from the case; he replaced them with new counsel. Fairey said he was initially mistaken about the source and then, embarrassed, tried to hide his mistake. “I made some poor decisions that I can only blame myself for,” he told me.

The change in source affected one tenet of his fair use argument: that he “used only a portion of the Garcia Photograph, and the portion he used was reasonable in light of Fairey’s expressive purpose.” The artist’s misstatements may have kept the case from going to the Supreme Court and setting a legal precedent. At the urging of a judge, Fairey and the AP settled out of court at the start of 2011, with an undisclosed financial settlement; neither party surrendered its view of the law. In 2012, Fairey pleaded guilty to criminal charges of destruction of evidence and was sentenced to three hundred hours of community service.

Does Shepard Have a Posse?

Even before Fairey’s admitted lie, he had a credibility issue. The Internet is full of Shepard-haters: Diehard punks and radical left-wingers accuse Fairey of selling out, not just because he created ad campaigns for Levi’s and Saks Fifth Avenue, but also because of the Obama posters. Sarah Banet-Weiser has critiqued Fairey and other street artists, such as Banksy, as being peddlers of their own brands, the ultimate creative entrepreneurs in a neoliberal postcapitalist apocalypse world. He’s a copycat, critics say: One website is dedicated to listing the artists and works Fairey has allegedly plagiarized. Undoubtedly some of these attacks come from artists who are jealous of his success. Others, like Banet-Weiser, have fairly well thought-out critiques. When I wrote an article on Fairey for the Miami Herald in November 2009, it quickly accrued comments both from kneejerk radicals and reasoned liberals troubled by Fairey’s questionable integrity. Sometimes, it seems as if Fairey has a posse—one that’s out to hang him.

The criticisms that have the most disturbing implications for the artist’s reputation are the charges that while Fairey unapologetically appropriates, he has been litigious toward people who have in turn appropriated his work. For instance, in 2008 he sent a cease and desist letter to Baxter Orr, an Austin artist and art dealer who had made a version of Fairey’s iconic “Obey” image with a surgical mask on it (apparently a reference to the SARS epidemic that had killed almost one thousand worldwide). Orr told the Austin Chronicle, “It’s ridiculous for someone who built their empire on appropriating other people’s images. Obey Giant has become like Tide and Coca-Cola” (quoted in Whittaker 2008).

When questioned about this, Fairey offered a somewhat torturous explanation of his actions. He said he was upset because Orr had been profiting off the artist’s work by buying posters cheaply from Fairey’s website—in true punk rock fashion, Fairey keeps prices for his work low—then flipping them for a substantial profit. Since this practice is only unethical, not illegal, Fairey went after the “parasite” (Fairey’s term for Orr) over IP infringement instead. Fairey also complained that Orr, who later made the disturbing “Dope” poster parodies of Obama as a cokehead, had publicly bragged about his actions and needled Fairey. Fairey said the letter was a mistake. “I didn’t think about how it looked hypocritical. I was operating out of anger and frustration.”

One could argue that Fairey’s admitted “mistakes” make him human. My personal assessment is that as a white kid from South Carolina, Fairey will always be an outsider in the outsider worlds of punk and hip-hop. This makes him both insecure and vulnerable to attacks from those who consider themselves insider purists (like Orr). I think Fairey considers the current, constrictive rules of copyright law a burdensome and unreasonable hindrance to the cultural practices to which he, and increasingly many new media workers, are accustomed, and that he felt therefore above the law when it came to admitting the source of the Obama image. His hypocritical defense of his own intellectual property against another’s culture jamming both reveals his ego and shows just how complicated the politics of appropriation can be. Even those who see copyright law as being intrusive may see it as also necessary, especially when it comes to their own works.

Fairey is much more careful about attribution and appropriation since the AP skirmish. He undertook a project on American pioneers in art, music, and culture, starting with Rauschenberg associate Jasper Johns—thus saluting some of the figures others have accused him of stealing from. On his website, he carefully notes the Johns image is by photographer Michael Tighe (“Jasper Johns” 2009). He increasingly collaborates with photographers; a 2013 print of rocker Joan Jett is a Shepardiziation of a Chris Stein photo, for instance.

“I’m not trying to steal people’s images and exploit them,” Fairey said. “I feel like anything I make, I’m adding new value that doesn’t usurp the value of the original. At the same time I don’t want people to feel taken advantage of, so if I can make it be mutually beneficial, I will. This has never been about me trying to be selfish or greedy about the art I make. I try to use my art for good causes. Almost every print I do has some philanthropic element.”

Free Speech + Free Culture = Democracy

Lessig and Litman have both documented at length how the companies that are able to buy the most lawyers and legislators are currently winning the copyright wars. The AP said it was out to defend the rights of creators, but Mannie Garcia, the creator of the Obama photo, has both contested the organization’s ownership of the image and said he thought Fairey’s use of it had been a mostly positive experience:

I don’t condone people taking things, just because they can, off the Internet. But in this case I think it’s a very unique situation. . . . If you put all the legal stuff away, I’m so proud of the photograph and that Fairey did what he did artistically with it, and the effect it’s had. (Quoted in Kennedy 2009)

Copyright wars are not being waged by creators against other creators. They are being waged by the companies who have purchased the rights from the creators and are now cynically fighting to control creativity. But copyright law was invented precisely to counter such monopolization, when British Parliament passed the Statute of Anne to break the stranglehold booksellers had on literature. Today’s corporate media is every bit as powerful as those eighteenth-century word lords.

Many scholars who are closely studying the way new media is redefining cultural practices have regarded the AP-Fairey case as an important landmark. Jenkins argues that images of public figures should be seen as particularly fair game for culture jammers and remixers, as the art of Reid and Prince has already put into practice. “Artists—whether professional or amateur—need to be able to depict the country’s political leadership and in almost every case, they are going to need to draw on images of those figures which come to them through other media rather than having direct access,” said Jenkins. “The question, then, boils down to what relationship should exist between the finished work and the source material. And my sense is that Fairey’s art was transformative in that it significantly shifted the tone and meaning of the original image. . . . The mythic power comes from what Fairey added to the image—not from any essential property of the original, which was workmanlike photojournalism” (pers. comm.).

The most disturbing ramification of the case against “Hope” may be its chilling impact on free speech and civic engagement, the backbones of democracy. Media organizations such as the AP have seen their revenues shrink as readers move from print to digital and mobile platforms, and they have watched as their content disperses over the web—with little or no recompense. The news company tried to make an example out of Fairey (they have also fought aggregators such as Google News). The skateboard punk artist sought a new, wider audience with “Hope”—he got it, but he also got dragged through the legal and PR mire. If Fairey were to consider making the Obama poster now, he might not simply license the photograph; he might remain silent all together. “I still don’t regret it, though I’m a lot closer to regretting it than I ever thought I would be,” he said in 2009. “It’s such a nightmare that I’m going through. It’s been really hard on my family.”

Fairey’s art makes sense—not just to punks, rappers, and culture jammers, but also to every Harlem Shaker who finds a thriving creative environment in the frontier world of the Internet. Appropriation is part of how they create and communicate every day. “[Fairey] embodies this new dispersed, grassroots, participatory culture about as well as any contemporary figure,” said Jenkins. “The battle between AP and Fairey is an epic struggle between the old media and new-media paradigms, a dramatization of one of the core issues of our times” (pers. comm.).

In Free Culture, Lessig (2004) argues that the divergence between copyright law and public practice is turning regular citizens into outlaws and thus undermining the rule of law. The Harvard scholar and founder of Creative Commons publicly backed Fairey in his fight with the AP. Fairey probably didn’t exactly mean to launch a grenade into this legal battleground when he created the most populist, crossover work of his life. But since his entire oeuvre is rooted in culture jamming practices, perhaps he couldn’t help but be a guerrilla.

The “Hope” poster won its first objective: Barack Obama was elected president on November 4, 2008. It also made Shepard Fairey a celebrity. And though Fairey et al v. The Associated Press was an inconclusive legal battle, it was a highly public skirmish in the copyright wars that challenged the way we both think about and litigate cultural creation in the twenty-first century. GIFs, memes, viral videos, parody videos, literal videos, fan fiction, modding—most Internet discourse is cannibalistic to some degree: It involves taking something that has been made before, and finding new meanings by reworking it. If an accomplished artist has his hands royally slapped for creating something as clearly iconic as the Obama campaign poster, what does that mean for the ten-year-old future Shepard Fairey posting videos of himself playing Grand Theft Auto on YouTube? The “Hope” case raised public awareness of how easily technology allows people to appropriate other works with a few clicks of a mouse and to question not only when that is legal, but when it is ethical, when it is transformative, when it is fair use, and when it is art.

Notes

1 This and all subsequent quotations from Fairey that are not cited in notes are from an in-person interview conducted by Evelyn McDonnell (see Fairey 2009b).

2 “Sex Pistols Artwork,” SexPistolsOfficial.com, www.sexpistolsofficial.com.

3 Shepard Fairey and Obey Giant Art v. The Associated Press, Complaint for Declaratory Judgment and Injunctive Relief, 11, docs.justia.com.

4 Shepard Fairey and Obey Giant Art v. The Associated Press, Answer, Affirmative Defenses, and Counterclaims of Defended, The Associated Press, 10, docs.justia.com.

5 Paul Colford, “AP Statement on Shepard Fairey Lawsuit,” Associated Press, February 9, 2009, web.archive.org.

References

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2012. Authentic™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Chang, Jeff. 2005. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York: Picador.

Colford, Paul. 2009. “AP Statement on Shepard Fairey Lawsuit.” AP, February 9. www.ap.org.

Fairey, Shepard. 2009a. “Art, Culture, Politics: A Conversation with Shepard Fairey.” Q & A with Sarah Banet-Weiser, Norman Lear Center Annenberg, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, November 4, 2009.

———. 2009b. Interview by Evelyn McDonnell, November 18, 2009.

Fairey, Shepard, et al. 2009. Obey: Supply and Demand; The Art of Shepard Fairey. Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press.

Goldstein, Paul. 2003. Copyright’s Highway: From Gutenberg to the Celestial Jukebox. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

“Jasper Johns.” 2009. Obeygiant.com, December 10. www.obeygiant.com.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, Henry, Katie Clinton, Ravi Purushotma, Alic J. Robinson, and Margaret Weigel. 2006. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Chicago: MacArthur Foundation.

Kennedy, Randy. 2007. “If the Copy Is an Artwork, What’s the Original?” New York Times, December 6.

———. 2009. “Artist Sues the A.P. over Obama Image.” New York Times, February 9.

———. 2011. “Shepard Fairey and the A.P. Settle Legal Dispute.” New York Times, January 12.

Lessig, Lawrence. 2004. Free Culture. New York: Penguin.

Litman, Jessica. 2006. Digital Copyright. Amherst, NY: Prometheus.

Sex Pistols. 1977. Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols. Warner Bros., compact disc.

Shapiro, Peter. The Rough Guide to Hip-Hop. London: Penguin.

Whittaker, Richard. 2008. “Artist Cage Match: Fairey vs. Orr.” Austin Chronicle, May 16.