Artist A]

Artist A]  Index A]

Index A]  Recipient P

Recipient PSculpture and Agency at the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of the First Emperor of China

This paper explores the potential of Alfred Gell’s theory of agency for studies in comparative art, by means of an examination of the role of figurative representation in the tombs of an early Greek and an early Chinese monarch. Comparative art is a field of enquiry which periodically seems on the point of breaking through to equivalent disciplinary significance to that of comparative religion or comparative literature. But it seems never quite to cross the threshold. As a gross generalization, one might say there are two broad approaches, neither very satisfactory. One would be cross-cultural aesthetics, exemplified by Richard Anderson’s (2004) Calliope’s Sisters. Anderson’s book compares a series of seven aesthetic systems and concludes that each is ‘truly a unique entity, fundamentally unlike all others’ in so far as each embodies a culturally distinctive cosmology or tradition of meaning (Anderson 2004: 253). An alternative would be the broadly comparative sociological approaches of archaeologists like Timothy Earle (1990) and Bruce Trigger (2003: 541–83). They have looked at parallelisms in the transformations of style and monumentality in the development of chiefdoms, and their transformation into states. Whilst interesting, the parallels are very gross and abstract from the specific artistic and material characteristics of the monuments which might seem most in need of explanation.

Gell’s (1998) account of art as agency offers one helpful way of moving beyond these dichotomies. Unlike the reductionist approaches of Earle or Trigger, Gell is very much concerned to engage with the specific material properties of images and their affordances.1 He criticizes contemporary approaches to the history and anthropology of art which he sees as oriented to the needs of the modern museum-going public in its efforts to recover the symbolic meanings of alien traditions and to celebrate their aesthetic achievements. Gell instead approaches art in terms of its efficacy, which he conceptualizes in terms of ‘agency’. Human beings, primary agents, act in and on the world through material interventions, above all through the artefacts, secondary agents, which render their agency effective, like the guns which are an intrinsic component of a soldier’s agency. Art’s specific agency is grounded in what Gell (1992) calls ‘technologies of enchantment’ – displays of technical skill which surpass the viewer’s understanding, inducing on the part of the viewer or ‘recipient’ the abduction of special powers on the part of the artist who produced the image, or the patron who occasioned its production. Through this halo effect of technical difficulty the viewer is awestruck into acquiescence in the projects of the patron/producer. The canoe prow boards of the Trobriand islanders, for example, were not so much ‘works of art’ in the sense we understand the term as weapons in the psychological warfare which informed kula exchange. Ritually prepared painter-magicians embellished such boards with elaborate designs, based on radiating circles, painted in bright colours and with strong tonal contrasts. This perceptually striking imagery captivated the viewers of such prows – potential traders waiting on the shores – loosening their grasp on their wits and thus compelling them to trade their kula shells at a lower value than might otherwise have been expected (Gell 1992: 44–45; 1998: 68–72).

Gell’s approach is codified in ‘the art nexus’ where the core set of logically possible causal relationships between his key theoretical terms is tabulated: artist, index, prototype and recipient can all stand in reciprocal relationships of agency and patienthood to each other. A viewing of Reynolds’ portrait of Dr Johnson may be analysed as an instance of a passive spectator being ‘causally affected by the appearance (or other attributes) of a prototype of an artwork (the index), when this attribute is seen as itself causal of this response’ (Gell 1998: 52). Johnson’s posture in Reynolds’ portrait, a posture which dominates the viewer, encourages feelings of awe towards this English national figure, feelings which also affected the painter Reynolds, and thus shaped his portrayal of Johnson (Gell 1998: 52–53; Tanner and Osborne 2007: 15).

Gell formalizes the representation of such agent/patient relationships by means of a simple algebra. The attraction of these formulae is that they help to highlight fundamental cognitive and social affinities – or indeed structured patterns of difference – that may relate practices of artistic representation across cultural boundaries. Portraits can be described by the formula:

[[[Prototype A]  Artist A]

Artist A]  Index A]

Index A]  Recipient P

Recipient P

The physical facts of the prototype’s appearance causally constrain the artist in forming an index by which the viewer is affected, by virtue of inferring the prototype’s appearance and character from the index. As such, this does not take us very far; but there are two kinds of games one can play with such formulas. One is a deductive procedure, playing around with the formula, seeing what logical variations might exist, where they in fact occur, and why. Thus, placing the artist before the prototype in the above formula would produce an expression which corresponds to the role of the portrait in modernism’s artist-centred art world, where the agency of the artist plays the primary role, not that of the sitter – like Picasso’s Kahnweiler. An alternative strategy is to focus on the arrows of the formula, exploring exactly how the prototype causally determines the character of the index. What is the character of the material technology that binds the prototype to the index? And how does this inform the character of the agency transmitted from prototype to recipient? This is the approach I wish to adopt in this essay, focusing on tombs as objects which are primarily concerned with the extension of personhood beyond the confines of biological life by means of a sometimes very elaborate index distributed in the causal milieu.

One could formulate a concept of the tomb as an extension of personhood as follows:

[[[Recipient1 A]  Artist A]

Artist A]  Index A]

Index A]  Recipient2 P

Recipient2 P

The primary recipient, or patron, causes the artist to produce an index, of which the characteristics have a certain impact on a secondary recipient, or recipients, presumably some kind of abduction of the agency of the patron. I shall use this formula to explore the similarities and differences in the use of figurative representations – my indexes – in the case of two royal tombs, those of Mausolus of Caria and Qin Shihuangdi, the First Emperor of China. First, I offer a very basic sketch of the two tombs, and of earlier accounts of them, which have been in certain respects oriented towards contemporary art appreciation or the decoding of symbolic meanings – the kinds of approach of which Gell is so critical. Then I will seek to rework the material, by focusing on the specific character of the causal agency manifested in each case at each arrow in the formula. To summarize: I will argue that the ways in which figural imagery is used – its placement, the material techniques used in its production, the social realization of its production, in short, the technologies of enchantment – are informed by the distinctive conceptions of the agency of images characteristic of the Greek and Chinese worlds at the times in question, and by differing beliefs on the part of Mausolus and Qin Shihuangdi about the kind of agentic power which could be transmitted from the world of their life to that after their death.

Mausolus succeeded his father as satrap of Caria in 377 BC. Notionally subordinate to the Great King of Persia, he co-ruled with his sister-wife Artemisia until his death in 353 BC. He took advantage of Persian weakness to carve out Caria as an independent kingdom, in the south-west corner of modern Turkey. The Mausoleum itself was started in circa 367, when Mausolus moved the capital of his kingdom from Mylasa to Halicarnassus, which he refounded through an act of synoikism, transferring the populations of at least four inland communities to this coastal site. This new capital provided the basis from which Mausolus developed an expanding south-east Aegean empire, annexing Rhodes and Chios during the 350s and developing hegemonic influence over communities in Crete, Pamphylia, Posidia and Ionia (Jenkins 2006: 203–6).

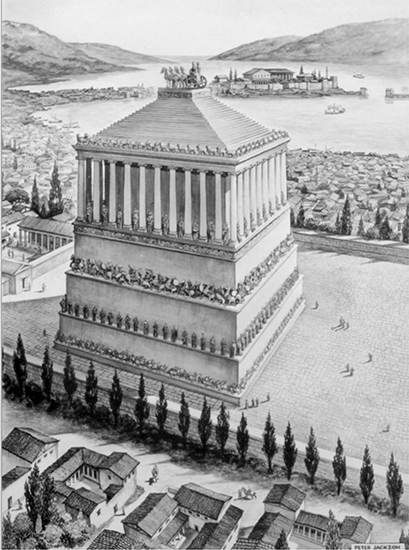

Mausolus’ tomb was envisaged from the moment when he refounded Halicarnassus.2 The grid-plan left a space reserved for his funerary precinct right in the centre of the city, from where the towering monument that emerged dominated the surrounding buildings and was visible from the harbour (Figure 3.1). The Mausoleum was designed by Pytheos of Priene in collaboration with four of the most famous Greek sculptors of the fourth century BC: Scopas, Bryaxis, Leochares and Timotheus or possibly Praxiteles. The vast edifice takes the form of a temple-like shrine placed on top of a huge base. The roof was composed as a stepped pyramid, crowned by a chariot with four horses. The bottom step of the base had life-size statues of Greeks and Persians fighting; the next step up had a series of 11/3 life-size statues, subject indeterminate. The next step up had colossal statues of Greeks and Persians hunting panthers and boars, along with a scene of sacrifice. Immediately below the stylobate, there is a frieze showing an amazonomachy, perhaps the best preserved component of the Mausoleum sculptures, and one to which we will return later. Between the columns, wearing a mixture of Greek- and Persian-style clothing, was a series of 12/3 life-size statues, probably a gallery of ancestors, of which the two best preserved figures – a man possibly holding a sacrificial bowl and knife, and a woman in mourning – have been named, without specially good reason, Mausolus and Artemisia. A chariot frieze encircled the cella of the shrine, and a centauromachy the base of the vast chariot which crowned the monument.

Such a programme of course lends itself to iconographic interpretation, as the embodiment of a kind of eschatological allegory, which the great German iconographer Erwin Panofsky ([1964] 1992: 23–24) decodes as follows:

3.1 Tomb of Mausolus of Caria, Halicarnassus, c. 350 BC. Reconstruction by Peter Jackson. Courtesy of Geoffrey Waywell.

Both the battle between Amazons and Greeks and the battle of the Centaurs evidently express, here in unequivocally mythological form, the conflicts and triumphs of a heroic life, and the chariot race – a prelude as it were to the crowning quadriga – would seem to add the idea of a moral victory which, in conjunction with the military and political ones, entitled the dead ruler to a place among the immortal gods. Plato (Phaedrus 248) compares the efforts of the soul to reach a sphere wherein it may participate in the majestic motion of the stars to a race of charioteers . . . and Horace (Carmina I.1) speaks of the godlikeness of those who were victorious in a chariot race . . . Thus both the racing frieze and the crowning quadriga add up to one impressive symbol of apotheosis.

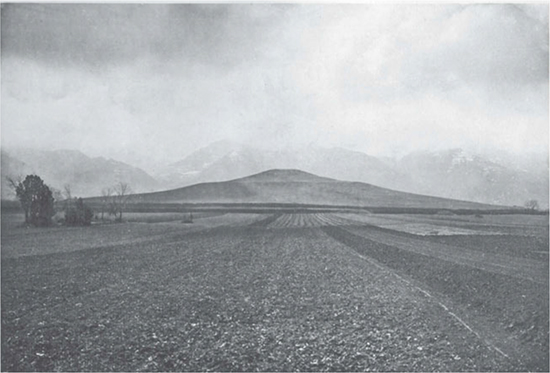

3.2 The Tomb Mound of the First Emperor, erected c. 221–210 BC. Photo by Victor Segalen, 1914. After Victor Segalen, Mission Archéologique en Chine (1914 et 1917), La Sculpture et les Monuments Funéraires. Paris 1923, plate 1. Courtesy of Editions Geuthner.

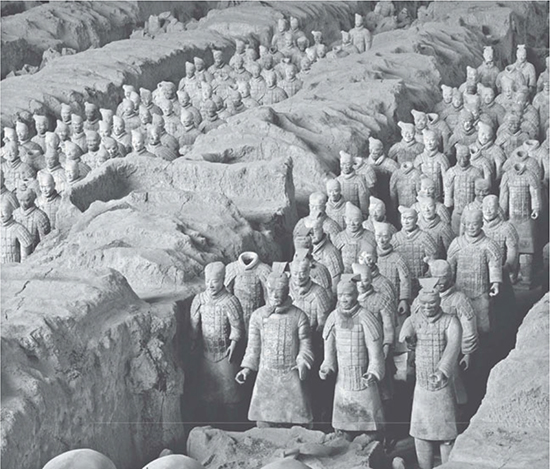

Like Mausolus, although on a grander scale, Qin Shihuangdi (260–210 BC) was a state builder (Loewe 2007). Over a period of decades he defeated the kings of the other states of China and incorporated their territories into his kingdom. Like Mausolus, the First Emperor certainly sought to impress himself upon his capital city. Whenever he defeated and annexed a neighbouring kingdom, he built in his own capital a new palace on the model of that of his newly conquered rival. His tomb, however, was placed at some distance from his capital, near modern Lintong in the foothills of Mount Li, a site set apart from the cemeteries of his ancestors, where his predecessors had been buried, in order to ‘demonstrate that he was not dependent on them for his supremacy’ (Rawson 2007: 124–25). The tomb complex itself is vast.3 At the centre is the still unexcavated tomb mound, shaped and planted as an analogue of a mountain (Figure 3.2). It covered a vast underground palace, set in a microcosmic landscape of China, with the Yellow River and the Yangtze fashioned in channels of flowing mercury. Surrounding the mound were a series of further pits. The contents of the pits within the inner funerary precinct included terracotta figures of officials and acrobats, as well as (real) wives and concubines who had accompanied the emperor to his death, alongside sacrificed favourite horses, laid out in stable quarters with terracotta grooms to tend them, and half-size but fully functional bronze chariots. Beyond the walls of the precinct were situated the pits in which the famous terracotta warriors were found (Figure 3.3).

3.3 The Terracotta Army. Pit 1. 221–210 BC. Photo: Terracotta Army Museum, Xian. Photograph: Juxian Xia and Yan Guo.

Like Mausolus’ tomb, that of Qin Shihuangdi has been the subject of much art historical reflection. Some interpret it symbolically as an embodiment of meaning, and more specifically of concepts of life and death, and of rulership and cosmology articulated by the First Emperor (Portal 2007: 21; cf. Kesner 1995: 131). Others have sought to trace the origins of the unprecedented figures, to models ultimately as far west as the Mausoleum itself, celebrating, like Richard Barnhart (2004: 330), ‘the welcome elevation of Chinese sculpture into the glamorous company of Greece and Rome’.4 A more sophisticated elaboration of the same argument sees the Terracotta Army as emulating the kinds of monumental public sculptures that some Chinese may have heard about, or even seen, being set up by the rulers of kingdoms in central Asia, India and possibly even further west – the precipitate of a kind of peer-polity interaction.5 Whilst there is almost certainly an important element of truth in this latter argument, it does not really help us to address what the figures were doing in the emperor’s tomb, where, after his death, they would have been completely invisible, thus turning the public sculpture of the classical world outside-in as it were.6 Another, more fruitful, direction of interpretation has been developed by Jessica Rawson (1999b: 16–18; 2007), along lines very much parallel to some of the ideas found in Gell’s Art and Agency. I take Rawson’s analysis as a starting point for exploring the kinds of material agency manifested in the funerary complex of the First Emperor, and how exactly they may have served to transmit his agency, and how these modes of agency might be compared with those characteristic of the Mausoleum.

Rawson’s argument starts from the specific character of the Chinese concept ‘xiang’ ( ) – ‘likeness’ or better ‘figuration’ – and its place in broader Chinese understandings of cosmology. Grossly simplified, Chinese cosmology of the period of the First Emperor conceptualized the material world as consisting in varying concrescences of ‘qi’ (

) – ‘likeness’ or better ‘figuration’ – and its place in broader Chinese understandings of cosmology. Grossly simplified, Chinese cosmology of the period of the First Emperor conceptualized the material world as consisting in varying concrescences of ‘qi’ ( ) – natural energy – which, under the alternating influence of yin and yang gives rise to all that exists, the ‘ten thousand things’ all linked in a series of five phases. All the features of the world, from the seasons and planets to the vital organs and colours, were correlated with each other according to this five-phase model. Analogies formed on the basis of this model facilitated control over the patterns of human life through their alignment with the correlative patterns of the natural world. In the context of this world view, natural phenomena could be interpreted as manifestations of the will of heaven, and the constellations of the visible astral bodies were interpreted as figurations of the way of heaven.

) – natural energy – which, under the alternating influence of yin and yang gives rise to all that exists, the ‘ten thousand things’ all linked in a series of five phases. All the features of the world, from the seasons and planets to the vital organs and colours, were correlated with each other according to this five-phase model. Analogies formed on the basis of this model facilitated control over the patterns of human life through their alignment with the correlative patterns of the natural world. In the context of this world view, natural phenomena could be interpreted as manifestations of the will of heaven, and the constellations of the visible astral bodies were interpreted as figurations of the way of heaven.

Xiang, images, were not just likenesses, but analogues, whose forms ‘correlated with eternal features of the universe’, affording practical entailments such as clay images of dragons having the power to attract the rain which was associated with such creatures (Rawson 1999b: 17; 2000: 134). According to this logic, Rawson argues, the representations of palaces and rivers, of officials and soldiers in the emperor’s funerary complex are not simply images, but analogues, which could function in the tomb to sustain an existence for the emperor in the world beyond, to replicate power exactly equivalent to that which he had enjoyed in his former life. Why the huge army? How else to protect himself against the aggrieved spirits of the defeated enemies slaughtered in the series of wars which had secured his position of First Emperor (Rawson 2000: 144; Rawson 2007: 120–45)?

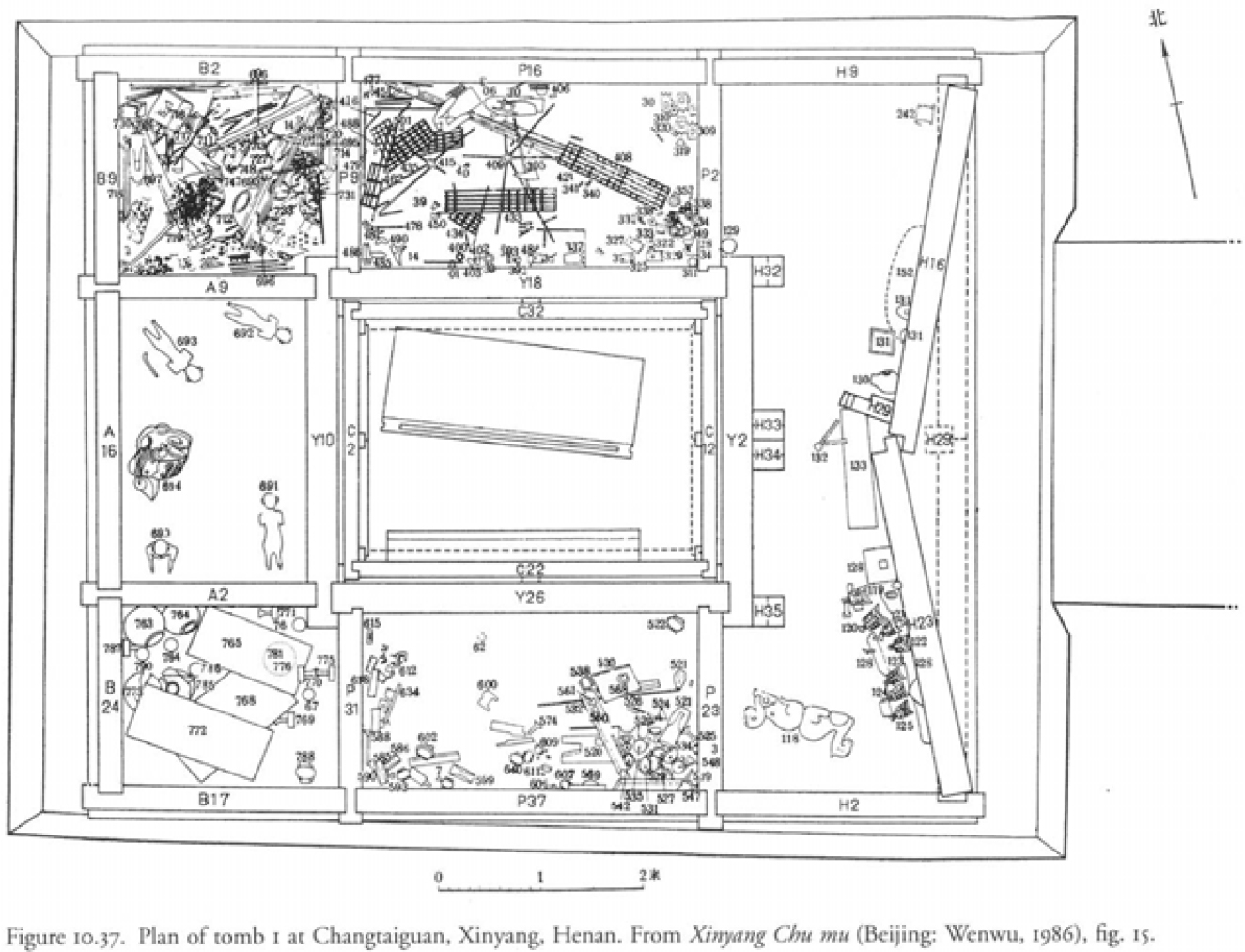

This line of argument should alert us to the possibility that thinking about the figures of the Terracotta Army in terms of the history of Chinese sculpture – born with a precocious naturalistic maturity attributable to ‘influences’ from the West – may be drawing us into a misleading account. If there was no ‘sculpture’ before the Terracotta Army there was certainly a tradition of material representation which anticipates key characteristics of the figures who accompanied the First Emperor (Wu 1999: 732–40). The production of tomb figures, yong ( ), is mentioned by Confucius as early as the sixth or fifth century BC. Confucius criticized the use of such figures, which he regarded as being too close to real human likenesses, and thus blurring the difference between representation and reality in a way which might seem to encourage human sacrifice in the context of funerals. His admonitions seem to have been heeded only very partially. The later Eastern Zhou period sees the increasing use of such figurines in parallel with a decline in the use of human sacrifices (Wu 2005: 13–15). The figurines are generally placed in compartments surrounding the coffins. These compartments contain a range of objects which define them as rooms with specific purposes: cooking utensils for a kitchen; musical instruments and bronze vessels, together with attendants, in audience halls, designed for ritual performances (Wu 2005: 15–20). An Eastern Zhou burial from Changtaiguan in Henan province, dated to the late fifth/early fourth century BC includes, to the north of the central coffin chamber, a compartment housing two model chariots with drivers (Figure 3.4). In the compartment behind it were found a couch, writing equipment, bamboo slips and two figurines representing secretaries, thus comprising a fully equipped study.

), is mentioned by Confucius as early as the sixth or fifth century BC. Confucius criticized the use of such figures, which he regarded as being too close to real human likenesses, and thus blurring the difference between representation and reality in a way which might seem to encourage human sacrifice in the context of funerals. His admonitions seem to have been heeded only very partially. The later Eastern Zhou period sees the increasing use of such figurines in parallel with a decline in the use of human sacrifices (Wu 2005: 13–15). The figurines are generally placed in compartments surrounding the coffins. These compartments contain a range of objects which define them as rooms with specific purposes: cooking utensils for a kitchen; musical instruments and bronze vessels, together with attendants, in audience halls, designed for ritual performances (Wu 2005: 15–20). An Eastern Zhou burial from Changtaiguan in Henan province, dated to the late fifth/early fourth century BC includes, to the north of the central coffin chamber, a compartment housing two model chariots with drivers (Figure 3.4). In the compartment behind it were found a couch, writing equipment, bamboo slips and two figurines representing secretaries, thus comprising a fully equipped study.

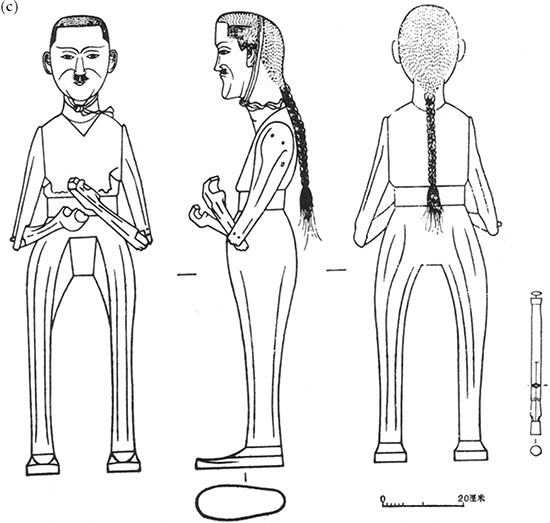

The carefully carved figurines have their clothes painted in black, with fine patterns representing expensive textiles, while fabric was glued to their sleeves, and hair to their heads, for added realism (Rawson 2002: 26–30; Wu 1999: 733–40; Wu 2005: 18–20). Such figurines are dressed and equipped appropriately to their roles, whether cooks, secretaries, musicians, entertainers, servants or guards. Amongst these figures, a range of representational strategies serve to suggest an equivalence between the index and the real human being which it stands in for (Figure 3.5 a–c). Some are brightly painted or have carefully modelled musculature; others wear fancy silk dresses, or sport real hair (Wu 2005: 32–38; So 1999: 40). Others – like the two large-scale figures from Baoshan, each more than a metre in height and originally draped with silk garments – even have articulated limbs, making it easier for them to perform the actions appropriate to their specific roles (Wu 1999: 736–39).

3.4 Plan of Changtaiguan tomb M1, Xinyang, Henan Province. Fifth to fourth century BC. After Xinyang Chumu (Beijing Wenwu Chubanshe, 1986), Fig. 15. Courtesy Wenwu Chubanshe.

Art historians like Barnhart overlook these figurines, presumably because such cheap tricks as articulated limbs and stick-on hair are not what we associate with a high art form like ‘sculpture’. Following Barnhart, Nickel (2009: 129) seeks to draw a radical distinction between the ‘sculptures’ (Plastiken) of the Terracotta Army and the figures from the earlier Chu and Qin tombs, mere ‘dolls’ (Puppen).7 This is not persuasive. The use of the terracotta figures of the First Emperor’s tomb parallels that of the figures in earlier Chu and Qin tombs, and later Han tombs, since in both cases figures with attributes suitable for performing specific roles (groom, scribe, warrior, etc.), are placed in distinctive chambers within the tombs, designed for the performance of those specific functions (Rawson 1999b: 31–32; So 1999: 38).8 Similarly, the use of real weapons and armour with the same lacquered surface treatment as real armour blurs the boundary between ‘reality’ and ‘representation’ amongst the terracotta warriors by means of strategies of materialization which closely parallel the use of real clothes and hair in the earlier figurines.

3.5 Early Chinese funerary figurines.

(a) From Mashan, Jiangling, Hubei. Fourth century BC. After Jiangling Mashan yihao Chumu (Beijing: Wenwu, 1985), plate XXXI. Courtesy of Wenwu Chubanshe.

(b) Wooden figure of a warrior, from a fourth century BC Chu tomb. John Hadley Cox Archaeological Study Collection, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Gift of John Hadley Cox, 1991. Photographer: John Hadley Cox, 11.1.

Against this background, the Terracotta Army represents simply an extension of a long-existing tradition of material representation, using supplementary means to blur the boundary between index and prototype, most obviously life-size scale and a kind of modular system of mass production which lent an apparent variety to the figures, and extraordinary realism in the detail of their modelling.9 Of course, like his predecessors, Qin Shihuangdi did not hesitate to take hyperrealism to the ultimate level: the wives and concubines who were buried with him as companions in death (ren xun,  ) must have been very realistic indeed, also with nice silk dresses, lovely black hair, and moveable limbs. What Gell (1998: 153) calls the ‘insensible transition’ between living beings and intersubstitutable art objects is nicely illustrated by the stables, where the bodies of the emperor’s favourite horses are accompanied by [terracotta figures of] their grooms (Rawson 2007: 138, figure 144).10

) must have been very realistic indeed, also with nice silk dresses, lovely black hair, and moveable limbs. What Gell (1998: 153) calls the ‘insensible transition’ between living beings and intersubstitutable art objects is nicely illustrated by the stables, where the bodies of the emperor’s favourite horses are accompanied by [terracotta figures of] their grooms (Rawson 2007: 138, figure 144).10

(c) From Bao Shan, Hubei. After Bao Shan Chu mu (Beijing: Wenwu, 1991) Vol. 1, Fig. 170. Courtesy of Wenwu Chubanshe.

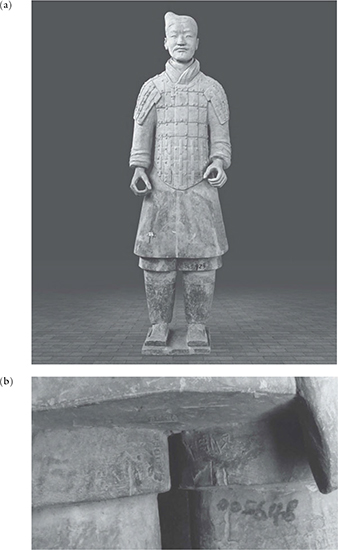

The new means employed by the First Emperor in the production of the life-size terracotta figures amplified the mediation of imperial agency in comparison with that effected by the earlier miniature figurines in a number of interesting ways, both before and beyond the grave. As we have seen, close equivalence between index and prototype seems to have been important to how these objects were supposed to operate. Correspondingly, quality control was at a premium: no room for poorly fired soft soldiers, potentially weak at the knees in the face of the emperor’s spirit enemies. Quality was maintained through bureaucratic organization of production. The name of the foreman of the team responsible for the production of a figure would be inscribed on the back of the figure, or stamped with a personal seal, sometimes with the inscription ‘gong’ ( ‘palace’), identifying the specific palace workshops and the directorate which oversaw the work (Barbieri-Low 2007: 7–9; Nickel 2007: 179; Figure 3.6 a–b). Such signatures or makers’ marks serve not so much to individuate the artists who produced the figures as to render them perfectly passive to the implementation of the emperor’s project, through the surveillance and control he was able to exercise over them.

‘palace’), identifying the specific palace workshops and the directorate which oversaw the work (Barbieri-Low 2007: 7–9; Nickel 2007: 179; Figure 3.6 a–b). Such signatures or makers’ marks serve not so much to individuate the artists who produced the figures as to render them perfectly passive to the implementation of the emperor’s project, through the surveillance and control he was able to exercise over them.

Just like the emperor’s earthly army, so the Terracotta Army was occasioned by, and a manifestation of, the agency of the emperor, right down to the weapons with which they were equipped, real swords and halberds, still sharp today. Indeed, the weapons are inscribed with the details of their date of production and name of producer, in the palace workshops. In some cases their production date is as early as 245 BC, suggesting they were stored in the imperial armoury before their use by the terracotta warriors, and had perhaps even been used in the military campaigns of the First Emperor (Yates 2007; Nickel 2007: 174–75). The agency which had occasioned the technologically superior army which had secured the unification of China under Qin Shihuangdi’s rule was thus replicated in a virtually identical manner in the artistic production which occasioned the Terracotta Army, ensuring that the transmission of the emperor’s earthly agency would be undiminished beyond the grave. Just one small but crucial alteration was needed, some special equipment for a specially challenging environment: suits of stone armour reputedly capable of protecting their wearer against the spells of the spirits and demons of the world beyond, who were, after all, the most important of the anticipated viewers and opponents of the emperor’s new model army (Lin 2007; Rawson 1999a: 124–25; Rawson 2007: 140).

If the primary recipients of the figures in the First Emperor’s tomb complex, after the emperor himself of course, were the inhabitants of the world of the dead, the primary recipients of Mausolus’ tomb and its lavish sculptures were in the world of the living. Mausolus’ tomb chamber was indeed (by comparison with Qin Shihuangdi’s if not the average Greek tomb) a fine and private place, just a few metres square, leaving not much room to squeeze around the sarcophagus in which the corpse was placed. There was no room for any kind of post-mortem embrace: when Mausolus sister-wife Artemisia joined him in the tomb, a few years after his death, her sarcophagus had to be placed in an antechamber outside (Jeppesen 2000: 103). Qin Shihuangdi would probably not have been impressed. Nevertheless, as we shall see, Mausolus’ tomb mediated his agency beyond death in ways every bit as powerful as in the case of the First Emperor, but it did so on the basis of significantly different understandings of what kinds of agency might be transmitted beyond death, and the ways in which visual art might materially mediate such agency.

3.6 (a) Terracotta armoured infantry man, from Pit 1. 221–210 BC. Photograph: Juxian Xia and Yan Guo.

(b) Characters identifying responsible producers, on the back of a figure. Photograph: Hiromi Kinoshita.

Although there were contexts in which Greeks believed that images could have a living agency analogous to that of human beings, most notably in cult-statues, the dominant mimetic concepts of art militated against this (Vernant 1991). An eikon or ‘image’, the nearest equivalent for the Chinese concept ‘xiang’, was defined in terms of its difference from the true reality, the prototypes, which they represented. At two removes from true reality, the world of the cognizable forms, paintings and sculptures were mere phantoms, ‘really unreal non-being’, ‘playthings’ as Plato dismissively refers to them (Sophist 240b11).

Although some sects like the Orphics developed quite elaborate accounts of eschatological bliss, for the majority in the ancient Greek world there was not much thought of any very fulfilling existence in the afterlife. Separated from the body, the soul might, according to some intellectuals, rejoin the spark of the divine fire from whence it came. More popularly, the soul was conceived as enjoying a diminished status as a mere ‘eidolon’ – an image without substance, a phantom, sometimes represented flitting about the tombs of cemeteries on Attic lekythoi, more generally confined to the gloomy underworld ruled by Hades (Vermeule 1979: 7–11, 33–37; Garland 1985: 48–76). So attenuated was this existence that when Odysseus summons Achilles from the underworld the latter exclaims how much he would rather be the meanest living slave on his father’s estate, than the greatest former hero in the world of the dead (Homer Odyssey XI.489–91). Death, for the Greeks, was the great leveller – king and pauper enjoyed the same status: decaying corpse in this world, insubstantial shade in the next.11

Against this apparently unpromising background, what could a tomb and its images do? Mausolus’ tomb is described in contemporary sources as a mnema, a monument (Hornblower 1982: 232). The concept of monument today is so devalued by worthy but dull works of public art erected in the memory of worthy but dull public figures that it requires some exercise of the imagination to understand quite how powerful a role mnemata, monuments, of various kinds played in the articulation and propagation of cultural memory in ancient Greece. Like many aspects of Greek culture, concepts of memory and memorialization reach back to Homer, who immortalized the fame, the kleos, of the heroes of mythology in his poetry, ensuring that their deeds would be sung down through the ages (Foxhall 1995; Immerwahr 1960). Classical poets like Pindar also sought to immortalize contemporary athletic victors in their poetry. And they did so not by reference to their immediate ancestors, but by reference to those victors’ mythical and even divine ancestors whose vital seed was in a sense reanimated in the athletic victor. In the fifth and fourth centuries BC these concepts extended to works of prose, and to physical monuments. In his Histories, Herodotus (I.i) placed the Persian wars in the context of and on the level of the mythic conflicts between the Greeks and the Trojans. His purpose was that memory of the great and wonderful deeds, the megala kai thomasta erga, above all of the Athenians in the wars against Persia, should not be forgotten but, like the myths, should transcend ordinary human time and be extended into the future. Herodotus also refers to buildings like the pyramids of Egypt as erga, deeds or accomplishments. He describes in detail the measurements of the tomb of Alyattes, the father of Croesus of Lydia, indicating the effort involved in the construction of the tomb as a measure of the greatness of the king (Immerwahr 1960: 263–65).12

It is against this cultural horizon that we can begin to understand the specific character of the agency of the Mausoleum. At Mausolus’ funeral, celebrated in the theatre immediately in front of the precinct of his tomb, a prize competition was held for the finest orators of the Greek world to compete in delivering eulogies, amongst them Theopompos of Chios, Naukrates of Erythrae and possibly the famous Athenian orator Isokrates. A play, Mausolus, by the tragedian Theodektes, was performed – probably about a mythological namesake who prefigured Mausolus’ political success and offered a suitably Greek and heroic genealogy, traced back to the Dorian Herakles and Theseus of Athens, and to the emigration of Ionians to Asia Minor where they took Carian wives (Hornblower 1982: 261, 335).

Like the play, though more enduringly, the figurative sculpture of the Mausoleum permitted Mausolus to act on time itself. This was accomplished through what, on the model of Gell’s (1998: 251–58) analysis of Maori meeting houses, we might call a series of mythical and material ‘protentions’ and ‘retentions’. These stretchings forward and back in time served to augment the impression of Mausolus’ agency which any viewer might abduct from his tomb. The amazonomachy, with Herakles’ defeat of the Amazon queen Hippolyta as its focus, indexes both Mausolus’ heroic genealogy, and one of the major cult centres of Caria, the sanctuary at Labraunda where the axe of Hippolyta was preserved. Together with the frieze of the centauromachy, it frames the kingly achievements of Mausolus, represented in scenes of the hunt and the historical battles between figures of mixed Greek and Persian dress. Mausolus’ victories over men and beasts are depicted both as praiseworthy achievements analogous to their mythic analogues and as parallel manifestations of genealogical virtue inherited from his mythic forebears, depicted in those friezes.

Like Gell’s Maori meeting houses, the retentions of the Mausoleum were artistic and architectural, as well as iconographic. The most notable predecessor to which the Mausoleum looked back was the Athenian Parthenon, also placed in an elevated spot in the middle of a town, overlooking a theatre. The scale and the peripteral colonnade of the Mausoleum lend it a temple-like character (Hoepfner 2002: 418). The amazonomachy and centauromachy friezes of the Mausoleum looked back to the metopes of the same themes on the Parthenon. Just as Athens claimed hegemony in Greece by virtue of her defeat of the Persians at Marathon, memorialized in the Parthenon, and analogized in its centauromachy and amazonomachy metopes, so in framing the representation of his own kingly deeds in the battle scenes with amazonomachy and centauromachy friezes, Mausolus lays claim to succeed Athens as hegemon of the Greek world. One cannot look at the Mausoleum without looking back to the Parthenon, which Mausolus in his monument has surpassed. Presenting to the viewer the deeds of Mausolus in these terms, the Mausoleum projects Mausolus and his family into an extraordinarily exalted position, within the mythological history, the political history, and, as we shall see later, even the art history of the Greek world.

Just as the thematics of the sculpture and its programmatic organization enabled Mausolus to act on time past, refiguring it as a prefiguration of his and his dynastic successors’ historical destiny, so it enabled him to act on the future, ensuring his immortality not just as a great king, but as the founder of a dynasty which would endure in time. Placed at the centre of his newly founded city, the Mausoleum functioned as a kind of ‘ground zero’ for the history of Halicarnassus, the Greek world, and even the larger eastern Mediterranean. Everything leads up to Mausolus, and all will flow from him. The position of the tomb, in the centre of the city, suggests that it was intended to function as a hero-shrine for Mausolus as the founder of the city (Hornblower 1982: 251–61; Jeppesen 1994), and thus also to transmit his position of leadership to his descendants as part of the sungenes ethos, the innate familial virtue – in Gellian terms, the special agentic powers – which they inherited from their ancestors. The Mausoleum provided a frame for the transmission of that dynastic charisma in the context of the cult of Mausolus and his Hekatomnid ancestors, insistently impressing their claims on the tomb’s viewers.13

The content and the placement of the sculptures of the Mausoleum thus served to celebrate and aggrandize the agency of the tomb’s builder, and to facilitate the intergenerational transmission of a familial charisma. But it indexed and augmented Mausolus’ agency on another level as well. For the Mausoleum effectively to mediate Mausolus’ royal agency in any of the ways already mentioned presupposed that the Mausoleum itself should be worthy of praise (axios logou; Immerwahr 1960: 267–68), able to motivate sustained engagement on the part of viewers, the kinds of engagement that would ensure this was the one of the most looked at and most talked about monuments of the ancient world. This was achieved by contracting the sculptures to four of the most famous artists of the Greek world and their workshops: on the East Scopas, on the North Bryaxis, on the South Timotheos or possibly Praxiteles, and Leochares on the West. The tomb was still not complete even a few years after Mausolus’ death, when his sister-wife Artemisia also died. But, as the Roman art historian Pliny (Natural History XXXVI.30–1) tells us, ‘the artists did not abandon their work until it was completed, judging that it would be a monument of their own glory and their art; and to this day their hands compete – hodieque certant manus’.

The way in which Mausolus acted on his artists and how they acted on the index – the sculptures – is interestingly different from the way Qin Shihuangdi acted on his artists, and they on their indexes. These differences are internally related to the different kinds of agency that the two men’s tombs sought to mediate and transmit. For Qin Shihuangdi, minutely accurate replication of his soldiers was the key to their efficacy in protecting the emperor against the spirits of his defeated enemies in the world beyond the grave. Although there may be grounds for seeing some aspects of the ‘naturalism’ of the terracotta warriors, most notably their life-size scale, as indebted to Western models (Barnhart 2004; Nickel 2009), a peculiarly Chinese technical agency informed their production and thus their specifically aesthetic agency. The coroplasts who produced the figures of the Terracotta Army were not ‘artists’ or ‘sculptors’ as we might understand the term today. On the contrary, they were members of workshops which were also responsible for producing such every day objects as floor tiles, roof tiles and drainage pipes (Ledderose 2000: 51–74; Barbieri-Low 2007: 7–9; Nickel 2007). The legs of the warriors were modelled according to similar procedures and proportions as those used to create drainage pipes. The heads were produced using a mould-based system of modular production which had its roots in the ceramic skills developed for the production of Chinese ritual bronzes. Two types of legs could be combined with four types of boots, and three of shoes. Eight different types of face mould could be combined with a similar variety of prefabricated hair-buns, and so on. The extraordinary variety that this modular system permits is thus at the same time highly regulated and codified. As a result of this mode of production there is something disturbingly uniform about the figures of the Terracotta Army, notwithstanding their much vaunted variety and their extreme naturalism: ‘likenesses of no-one’, as one scholar has dubbed them (Kesner 1995).

These features are sometimes characterized in terms of a ‘lack’ of naturalism – measured against classical Greek norms, of course. Such a perspective seems to underestimate the extraordinary technical skill manifested by the figures of the Terracotta Army. More significantly, it ignores how this uniformity in variety is internally related to the traditional Chinese moulding skills – and modes of social organization of the production of art – employed in the manufacture of the terracotta warriors. These skills and methods were the social and technical foundation for the realization of the specific, politically and ideologically inflected, agency of the warriors. John Hay (1999: 247–52; cf. Hay 1983: 76–83) has argued that these standardized techniques of replication correspond to the concept of ‘fa’ ( – norm, mould or model), a concept which had political as well as technical connotations. It is the term normally translated as ‘law’ in English, and used of the ‘legalists’ (fajia –

– norm, mould or model), a concept which had political as well as technical connotations. It is the term normally translated as ‘law’ in English, and used of the ‘legalists’ (fajia –  ) who shaped the political ideology and practice of the Qin state. Just as weights, measures and scripts were rationalized into a uniform and coordinated system, so were people. They were organized into households which could not legally include more than one able-bodied male in their number; into ‘wu’ or mutual responsibility groups of ten persons, responsible primarily for reporting each others crimes to higher authorities (or for being punished collectively if they did not). People were ranked according to a system of some twenty statuses, determined by (codified) levels of achievement in their service on behalf of the state. They were punished according to the severity of their offences (categorized in a systematic hierarchy), and the miscreant’s rank in the official status hierarchy (Loewe 2007: 64–67, 70–75).

) who shaped the political ideology and practice of the Qin state. Just as weights, measures and scripts were rationalized into a uniform and coordinated system, so were people. They were organized into households which could not legally include more than one able-bodied male in their number; into ‘wu’ or mutual responsibility groups of ten persons, responsible primarily for reporting each others crimes to higher authorities (or for being punished collectively if they did not). People were ranked according to a system of some twenty statuses, determined by (codified) levels of achievement in their service on behalf of the state. They were punished according to the severity of their offences (categorized in a systematic hierarchy), and the miscreant’s rank in the official status hierarchy (Loewe 2007: 64–67, 70–75).

All these practices involved, literally or metaphorically, moulding and modelling, shaping people and practices to fixed standards. These practices of shaping to standards (fa) were, like figuring or imaging (xiang), perceived to be intimately connected in the links which were formulated between celestial order, imperial order, and the corresponding ordering of society realized through the organs of the imperial state (Hay 1983: 81).14 The strange uniformity amidst variety characteristic of the terracotta warriors, the specific product of their moulding to standards, was doubtless a desired component of the figures. It allowed them to effect in their viewers the same ordering which informed their production – a somewhat unsettling experience for modern viewers precisely because the character of personhood they inculcate is so different from that of modern Western individualism, notwithstanding that ‘naturalism’ provides a formal basis both for modern portraiture and for the figures of the Terracotta Army. Indexing the agency of Qin Shihuangdi, and the material state apparatuses at his disposal, the warriors of the Terracotta Army are designed to intimidate as a mass at a glance, not to engage sustained aesthetic contemplation (Figure 3.3).

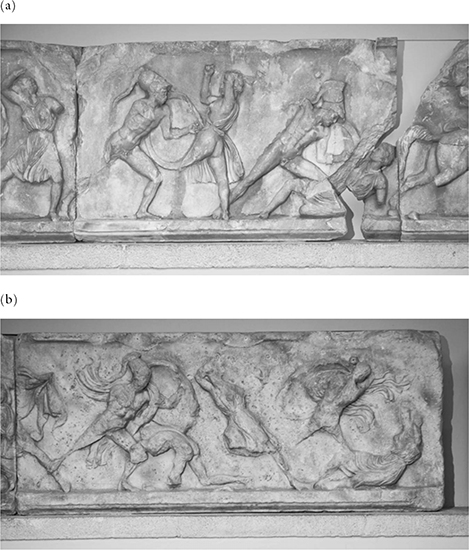

The sculptures of the Mausoleum, particularly the Amazon frieze, the best surviving component, though of course also ‘naturalistic’ in a general way, are, by contrast with the figures of the Terracotta Army, manifestations of extraordinary displays of individual artistic virtuosity – what Gell would see as examples of art’s power as a technology of enchantment. The varying design and proportions of the figures, the configuration of groups, the treatment of movement, the use of drapery to add drama or balance a composition: all these components foreground different styles of individual facture so distinctively that even today much scholarly ink is consumed, seeking to attribute different stretches of the frieze to different artists named by Pliny (Robertson 1975: 450–52; Cook 1989; 2005: 17–28; Wesenberg 1993: 172–78). Slab 1014 (Figure 3.7a) acquires its compositional structure from the rhythm of the four strong diagonals marked by its four figures, two pairs of duelling Amazons and Greeks. The figures themselves are compact and powerful, particularly the men with their superbly modelled muscular abdomens turned in three-quarters or frontally towards the viewer, each figure thrusting forward and gaining the upper hand against his Amazon opponent. The most distinctive figure of the group is the wonderful Amazon, whose tunic flies open as she wields her axe, revealing the fleshy forms of her breast and buttocks. Her twisting figure, framed by its drapery, seems to open the frieze into fully three-dimensional space. It recalls the famous Maenad by Scopas, similarly revealed by a twisting pose (Stewart 1990: figure 547), and the slab has therefore generally been attributed to Scopas or his workshop.

Slab 1021 (Figure 3.7b) has a rather different design. In place of the more traditional three-quarter and frontal views of slab 1014, the sculptor here explores ambitiously foreshortened perspectives from the back of figures, notably the two male figures second and fourth from right. The off-balance and momentary postures of the falling Greek and Amazon lend the scene an extraordinary immediacy which contrasts with the more statuesque, composed character of slab 1014. The drama of the scene is further enhanced by the use of dramatic wind-blown drapery, augmenting the impression of violent movement of the two victorious Greeks. This device was eschewed by the sculptor of 1014, perhaps because a background filled with agitated drapery would have distracted the viewer’s attention from the modelling of his figures and the space-creating torsion of his twisting Amazon, which were the primary devices through which he demonstrated his individual artistic virtuosity. The proportions of the figures of 1021 also differ from those of slab 1014 – taller and slimmer, with smaller heads, betraying the beginnings of a transformation in the canonical depiction of the male body characteristic of the generation of Lysippus, and perhaps amongst the Mausoleum sculptors best associated with Leochares (Robertson 1975: 450–52; Ashmole 1972: 168–73; Wesenberg 1992).

3.7 (a–b) Slabs 1014 and 1021 from the Amazonomachy Frieze of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, c. 350 BC. British Museum. Photographs: Stuart Laidlaw.

Like the clay of the Terracotta Army, the marble of the Mausoleum offered material affordances which reinforced the character of the agency the sculptures served to transmit. Cut marble, by contrast with the mould-made figures of the Terracotta Army, lent itself to the individual virtuosity in the design and carving of each single figure which we have already discussed. Marble was also a medium celebrated for its capacity to capture and reflect light. The Greek term for marble, marmaros, refers to the capacity of this crystalline stone to ‘shine and sparkle’ (marmairein, Steiner 2001: 214; with Liddell and Scott 1968, s.v. marmairo, marmaros, etc.). Even when painted, marble retains its capacity to absorb and retransmit light, so that the sculptures of a monument like the Mausoleum would have been characterized by a kind of living glow even in their polychromy. The use of marble quite literally lent an added lustre to the deeds of Mausolus and his ancestors which it celebrated. The visual properties of the sculptures, their complexity and luminosity, like those of some of the decorative objects Gell (1998: 72–95) discusses, both attracted the gaze and slowed viewing, creating an ongoing relationship between index and recipient. The Mausoleum sculptures operate by captivating their viewer, seducing him or her over time, into admiration of Mausolus as both king and connoisseur. The agency of Mausolus and the agency of his artists thus mutually index each other in a virtuous agency-augmenting recursive loop – even today, as Pliny pointed out: hodieque certant manus.

The difference between the two styles of material agency is perhaps nicely emblematized by how the two monarchs represented themselves, and in particular how they used material culture to operate on their own bodies in the tomb. Mausolus’ image was in all likelihood all over the Mausoleum: certainly in the hunting and battle scenes, possibly among the parade of ancestors, and also as an enthroned figure who was perhaps a focus for sacrificial offering in hero-cult.15 Qin Shihuangdi, by contrast, is more or less invisible even in his own tomb complex: this is in perfect keeping with how the tomb and its figures are supposed to operate. In contemporary political thought, the emperor’s authority was described not so much in terms of his personal power as in terms of the central position he occupied in the court, framed by layers of surrounding courtiers, feudal lords, barbarian chieftains and so on. So in the tomb, the emperor’s enduring authority is articulated by the empty places or positions, the wei ( ) which invoke his presence. These positions amongst his troops or in his chariot are left empty precisely in order for the emperor to be able to step into them (Wu 2005: 25–28).

) which invoke his presence. These positions amongst his troops or in his chariot are left empty precisely in order for the emperor to be able to step into them (Wu 2005: 25–28).

Until the tomb-mound is excavated, we cannot know exactly how the emperor’s body was treated, but we may be certain that it was processed in a way designed to preserve it intact over time. I would like to think that it involved a lot of jade, as was common for earlier Chinese royal burials, perhaps even a jade-suit like those worn by his Han successors (Rawson 1999b: 49–50). Such suits came complete with ear-plugs, nose-plugs and mouth stoppers – all designed to stop vital essence seeping out of the body through its orifices, or demons getting in and causing decomposition (Lin 2007). Only if he was preserved materially intact in this way could the emperor hope to take up the positions made available for him in the underground universe constructed by the terracotta figures who surrounded him in his tomb. The agency of the emperor, though exercised in a different realm than that of the living, is extended into an eternal present in the world beyond as a real bodily agency, just like that of the warriors, with their real, very sharp, weapons.

The proliferation of images of Mausolus works only because they are understood to be images of Mausolus, not analogues or substitutes. Material Mausolus, the body of the dead king, was placed in a sarcophagus in the tomb chamber. Sarcophagus literally translated means ‘flesh-eater’: in other words, it was a means (like cremation, which could conceivably also have preceded Mausolus’ burial) to unburden the deceased of his temporal fleshly encumbrances (Jeppesen 2000: 88–121). The material processing and entombment of Mausolus’ body thus serves to separate two Mausoluses: the bodily Mausolus of human time, represented in the battle and hunt sculptures, from the eternal Mausolus entering mythical or monumental time, represented in the chariot group on the top of the Mausoleum and in a sense by the Mausoleum as a whole. The human Mausolus is definitively dead, his finite bodily agency extinguished. But his funerary monument projects him into mythical time, materializing a form of agency which could be enduringly experienced by the monument’s viewers, and appropriated by Mausolus’ dynastic successors, in actual historical time.

How has the use of Gell’s account of art as agency enhanced our understanding of the sculptures of the Tomb of the First Emperor and the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus? The concepts of the art nexus, and the algebra of the Gellograms, have allowed us to analyse the two monuments in terms which are equally relevant and applicable to monuments from two radically discrepant cultures. That is to say Gell’s vocabulary makes the art of the two monuments commensurable. In doing so, however, it does not reduce them to their lowest common denominators, as some of the more positivistic paradigms in archaeology and anthropology might do: big tombs represent big men and their power (cf. Cherry 2007: 292). On the contrary, Gell’s emphasis on the material mediation of agency – from the patron (the primary ‘recipient’ and agent), to the artist, to the index, to the viewer (the ultimate recipient, and patient) – entails a detailed exploration of the cultural concepts, the social relations and the material practices which shape the relationships between the human and the artefactual domains at each juncture in this nexus.

This approach affords new and richer understandings of key aspects of both funerary complexes. We come to see how the materials and the specific artistic techniques used in the manufacture of the sculptures not only reflect a specific social organization of production, but also serve to (quite literally) impress on viewers, and thus transmit into the future, the specific character of the social agency of the rulers whose tombs they embellish. We see how different concepts of images, and the relationship between representation and ‘reality’, inform the social uses made of sculptures, the specific audiences to whom they are directed, and the material attributes with which they need to be endowed to exercise the agency required of them in their original contexts: from the real weapons and stone armour at the disposal of the terracotta warriors in their fight against the emperor’s enemies in the afterlife, to the fluttering drapery and ideal nudity of the figures on the friezes of the Mausoleum, which compels the attention and admiration of viewers for the dynastic charisma of Mausolus and his family, reaching back to the heroic age and stretching forward into an indeterminate future. At each level of analysis, the comparisons facilitated by Gell’s framework sharpen our perception of the specific character of the corresponding sets of choices made in the creation of the two sets of sculptures. Further, the comparative framework helps to drive forward the formal and the contextual – social, cultural, material – analysis which enables us to explain those choices and to understand their larger ramifications amongst the networks of people and objects of which these monuments were once a part.

Gell’s model of the art nexus, and his theorization of art as agency, has left us a powerful framework for the comparative analysis of art. Iconographic comparisons have, in the past, not taken us very far, coming up either with somewhat trivial parallels (kings tend to be represented on a larger scale than followers), or a stress on the incommensurability of the cultural meanings encoded even in images which look the same – the classic problem of iconographic disjunction. Comparisons starting from style almost always seem to presuppose one or other tradition – normally the Western tradition – as an aesthetic norm, comparing Chinese landscapes with Western ones largely in terms of the absence of perspective and chiaroscuro, or Egyptian sculpture with Greek in terms of the lack of naturalism. Archaeological and sociological approaches have afforded more ‘objective’ comparisons, focusing on the broad social functions of art, but generally without really getting to grips with the specific material characteristics of the art objects which engaged our interest in the first place. With the art nexus and an emphasis on the material mediation of agency, we are able to commensurate in an even-handed way the art objects of radically different cultures by means of a mode of analysis which insists that it is only through attention to the material specifics of the works of art that we can understand their simultaneously social and aesthetic agency.

Versions of this paper were given at conferences at the British Museum in 2008, in Cambridge in 2008 and at the Institute of Archaeology in 2010. I am grateful for the many stimulating comments and criticisms made by the audiences on all these occasions, in particular to Jessica Rawson and Lukas Nickel. I am also indebted to Wang Su-chin for comments on an early draft of this paper, and to the editors of this volume for their patience in awaiting the final draft. My thanks also go to the copyright holders of the images, for their reproduction permissions, as specified in the captions.

1. There are, of course, other recent approaches which move in a similar direction, focusing on issues of materiality and facture, notably Summers (2003) and Meskell and Joyce (2003); but this is not the place to discuss them.

2. The bibliography on the Mausoleum is extensive, and there is continuing debate over the exact character of the reconstruction of the monument, though not in details which would materially affect the arguments which I wish to make here. Jenkins (2006: 203–35) offers an excellent up-to-date discussion, and I largely follow his account throughout. For the broader historical context, see Hornblower (1982: 223–74).

3. As of course is the bibliography, particularly on the Terracotta Army. The best recent overview in English is Portal (ed.) (2007), with full bibliography, the essays in which provide the primary reference point for my account.

4. Cf. Nickel (2009: 125), who refers to the figures of the Terracotta Army as marking a ‘golden age’ (Blütezeit) of early Chinese sculpture.

5. This interesting argument was presented in a lecture by Lukas Nickel (2008). Nickel draws a parallel between the inscribed stelai erected by the First Emperor on the sacred mountains he visited during tours of inspection of his kingdom (see Kern 2007) and the inscribed pillars and rock carvings of Mauryan monarchs in third century India, like Ashoka (274–232 BC). Both these epigraphic practices, and the adoption of monumental sculpture, Nickel argues, can be seen as forms of emulation of rituals of rulership characteristic of kingdoms to the west of China. Nickel (2009) develops Barnhart’s linking of the terracotta warriors with Hellenistic sculpture in Afghanistan with evidence that the creation of some major bronze sculptures in the Qin capital Xianyang was connected by the First Emperor and his contemporaries with peoples beyond the western extremes of his realm.

6. Both Barnhart and Nickel use ‘influence’ as their primary theoretical concept in explaining the character of the figures of the Terracotta Army. This has the effect of minimizing the factors internal to Chinese culture which may have played a part in the openness of Qin China to such ‘influences’, and the particular way in which such putative influences were received, repackaged and transformed to play a role within Chinese concepts and practices of figurative representation. On the limiting character of the concept of influence, see Baxandall’s classic ‘Excursus against Influence’ (1985: 59–62) and, in the Chinese context, John Hay (1999: 247–52) on the Terracotta Army.

7. Gell’s comment (1998: 18) that works of art are simply adults’ dolls seems particularly pertinent here.

8. Though more rare in Qin areas than Chu in the last centuries of the Warring States period, the elaboration of this practice by the First Emperor and his Han successors is part of a larger process in the integration of Chinese culture in which Chu traditions seem to have been particularly favoured (Rawson 1999b, 7, 19–20, 30–49; So 1999). On early Qin tomb figures, see Hu (1981). On early Chu figurines, see Hunan Sheng Bowuguan (1959: 54–55, figs. 4–5); Shanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo (1984); Li (1993).

9. I do not mean to imply by this that knowledge of Western examples, at whatever degree of remove, may not have played a role in inspiring the Terracotta Army; only to put the receptivity of the First Emperor to such influences in a broader context. This involved: first, a long-term transformation in the institution of art in late Bronze/early Iron Age China (c.500–100 BC), in which figurative art played an increasingly important role, at the expense of the ornamental ritual bronzes which had almost exclusive predominance in the Bronze Age (Wu 1995: 77–142; 2005: 13–22; Rawson 2002); second, a long-term, and deepening, interaction between the group of states which came to form China and civilizational traditions on and beyond their Western borders (Rawson 1999b: 21–30). The unification of China, not surprisingly, intensified such processes to the point of marking a threshold transition (Rawson 1999b).

10. Sacrificed horses were also found on the steps leading to the grave chamber of the Mausoleum (Hoepfner 2002: 420), a traditional component of heroic sacrifice on the Homeric model, but of course without the kind of plastically modelled grooms of the tomb of the First Emperor.

11. The Mausoleum later became a rhetorical topos for the vanity of human wishes. In his Dialogues of the Dead, the Roman writer Lucian describes a conversation in the underworld between Mausolus and the Cynic philosopher Diogenes. Mausolus boasts of his great tomb, ‘outdoing that of any other of the dead not only in its size but in its finished beauty, with horses and men reproduced most perfectly in the fairest marble’. Diogenes mocks him, pointing out that Mausolus’ bald skull is as ugly as his own, and ‘with all that marble pressing down on you, you have a heavier burden to bear than any of us’; discussion Jenkins (2006: 209–10).

12. The pyramidal roof of the Mausoleum may well be intended to echo the pyramids of the pharaohs, as exemplary monarchic erga – Hornblower (1982: 244–51) with discussion also of Persian models which may be emulated by the Mausoleum.

13. The exact status of Mausolus after his death is a matter of some debate. One argument suggests that Mausolus was not just heroized, but divinized, and that this is implied by the Apolline imagery of the chariot ascending heavenwards on the roof of the Mausoleum (Hornblower 1982: 261). Either concept of Mausolus’ post-mortem status would be consistent with the argument I have developed, although the exact location and specific character of the familial charisma abducted from the Mausoleum would of course vary accordingly.

14. Hay (1983: 41) appositely quotes an explanatory passage in Guanzi, chapter 66: ‘The codification of fa: this is the fa-ing of the proper positions of heaven and earth, the imaging (xiang) of the passage of the [cosmic process in the] four seasons, for the purpose of governing sub-celestial existence.’

15. The state of survival of the sculpture makes certainty about the presence and placement of sculptures of Mausolus impossible. The best candidate amongst the surviving sculptures is the colossal seated figure, with purple cloak (Jenkins 2006: 218, fig. 215). Most scholars have argued that Mausolus was represented at least in the chariot, in the colossal sculptural groups (in the context of a hunting party on one side, in the performance of his duties as the ruler of Halicarnassus on the opposite side – Jeppesen 2000: 59) and in the life-size battle scenes. Confidence in such reconstructions is in part based on the multiple appearances of the king Erbinna on the Nereid monument from Xanthos (390–380 BC), one of the Mausoleum’s most important models (Jenkins 2006: 186–202), and of Abdolonymus, King of Sidon, on the so-called ‘Alexander Sarcophagus’, where the iconography of the animal hunt and of Greco-Persian collaboration seems indebted to the Mausoleum as predecessor (Stewart 1990: 193–95).

Anderson, R.L. 2004. Calliope’s Sisters: A Comparative Study of Philosophies of Art. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ashmole, B. 1972. Architect and Sculptor in Classical Greece. London: Phaidon.

Barbieri-Low, A.J. 2007. Artisans in Early Imperial China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Barnhart, R. 2004. ‘Alexander in China? Questions for Chinese Archaeology’, in Yang X. (ed.), New Perspectives on China’s Past. Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 329–43.

Baxandall, M. 1985. Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Cherry, J. 2007. ‘The Personal and the Political: The Greek World’, in S. Alcock and R. Osborne (eds), Classical Archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 288–306.

Cook, B.F. 1989. ‘The Sculptors of the Mausoleum Friezes’, in T. Linders and P. Hellström (eds), Architecture and Society in Hekatomnid Caria. Proceedings of the Uppsala Symposium 1987, Boreas 17. Uppsala, pp. 31–41.

———. 2005. Relief Sculpture of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Earle, T. 1990. ‘Style and Iconography as Legitimation in Complex Chiefdoms’, in M. Conkey and C. Hastorf (eds), The Uses of Style in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 73–81.

Foxhall, L. 1995. ‘Monumental Ambitions: The Significance of Posterity in Greece’, in N. Spencer (ed.), Time, Tradition and Society in Greek Archaeology: Bridging the Great Divide. London: Routledge, pp. 132–49.

Garland, R. 1985. The Greek Way of Death. London: Duckworth.

Gell, A. 1992. ‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’, in J. Coote and A. Shelton (eds), Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 40–63.

———. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hay, J. 1983. ‘Values and History in Chinese Painting’, Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 6 (Fall): 73–111.

———. 1999. ‘Questions of Influence in Chinese Art History’, Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 35 (Spring): 240–61.

Henan Sheng Wenwu Yanijusuo. 1986. Xinyang Chumu. Beijing: Wenwu.

Hubei Sheng Jinzhou Diqu Bowuguan. 1985. Jiangling Mashan yihao Chumu. Beijing: Wenwu.

Hubei Sheng Jinzhou Diqu Bowuguan. 1991. Bao Shan Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu.

Hoepfner, W. 2002. ‘Das Mausoleum von Halikarnassos: Perfektion und Hybris’, in W. Hoepfner et al. (eds), Die Griechische Klassik: Idee oder Wirklichkeit. Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, pp. 417–21.

Hornblower, S. 1982. Mausolus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hu Lin-gui. 1981. ‘Zaoqi Qin Yong Jianshu’ (A Review of Early Qin Tomb Figurines), Wenbo 1: 23–25.

Hunan Sheng Bowuguan. 1959. ‘Changsha Chu Mu’ (The Chu Tombs of Changsha). Kaogu Xuebao 1: 41–60.

Immerwahr, H. 1960. ‘Ergon: History as Monument in Herodotus and Thucydides’, American Journal of Philology lxxxi: 261–90.

Jenkins, I. 2006. Greek Architecture and its Sculpture in the British Museum. London: British Museum Press.

Jeppesen, K. 1994. ‘Founder Cult and the Maussolleion’, in J. Isager (ed.), Hekatominid Caria and the Ionian Renaissance. Halicarnassian Studies 1. Odense: Odense University Press, pp. 73–84.

———. 2000. Maussolleion Volume IV: The Foundations of the Maussolleion and its Sepulchral Components. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Kern, M. 2007. ‘Imperial Tours and Mountain Inscriptions’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press, pp. 104–13.

Kesner, L. 1995. ‘Likenesses of No One: (Re)presenting the First Emperor’s Army’, Art Bulletin 77(1): 115–32.

Ledderose, L. 2000. Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Li Baixun. 1993. ‘Shandong Zhangqiu Nulangshan Zhanguo Mu Chutu Yuewu Taoyong ji youguan Wenti’ (The Terracotta Figures of Musicians and Dancers Excavated from the Warring States Period Tomb at Nulangshan, Zhangqiu County, Shandong, and Related Problems), Wenwu 1993(3): 1–6.

Liddell, H.G. and R. Scott. 1968. A Greek English Lexicon. Revised and augmented by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lin, J. 2007. ‘Armour for the Afterlife’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press, pp. 180–91.

Loewe, M. 2007. ‘The First Emperor and the Qin Empire’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press, pp. 58–79.

Meskell, L.M. and R. Joyce. 2003. Embodied Lives: Figuring Ancient Maya and Egyptian Experience. London: Routledge.

Nickel, L. 2007. ‘The Terracotta Army’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press, pp. 158–79.

———. 2008. ‘The First Emperor of China’, paper delivered at the ‘Reigning Beyond Death – Tombs and World Rulers’ Conference, 15 March 2008. London: British Museum.

———. 2009. ‘Tonkrieger auf der Seidenstrasse? Die Plastiken des ersten Kaisers von China und die hellenistische Skulptur Zentralasiens’, in Zurich Studies in the History of Art/Georges Bloch Annual, Vol. 13–14, 2006/7. Zurich: University of Zurich, Institute of Art History, pp. 124–49.

Panofsky, E. (1964) 1992. Tomb Sculpture: Its Changing Aspects from Ancient Egypt to Bernini. London: Phaidon.

Portal, J. (ed.). 2007. The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press.

———. 2007. ‘The First Emperor: The Making of China’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press, pp. 14–29.

Rawson, J. 1999a. ‘Chinese Burial Patterns: Sources of Information on Thought and Belief’, in C. Renfrew and C. Scarre (eds), Cognition and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Symbolic Storage. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 107–33.

———. 1999b. ‘The Eternal Palaces of the Western Han: A New View of the Universe’, Artibus Asiae 59(1/2): 5–58.

———. 2000. ‘Cosmological Systems as Sources of Art, Ornament and Design’, Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 72: 133–89.

———. 2002. ‘Ritual Vessel Changes in the Warring States, Qin and Han Periods’, in Regional Culture, Religion and Arts before the Seventh Century. Papers from the Third International Conference on Sinology, History Section. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, pp. 1–57.

———. 2007. ‘The First Emperor’s Tomb: The Afterlife Universe’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum, pp. 115–51.

Robertson, M. 1975. A History of Greek Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Segalen, V. 1923. Mission Archéologique en Chine (1914 et 1917), La Sculpture et les Monuments Funéraires. Paris: P. Geuthner.

Shanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo. 1984. ‘Shanxi Changzixian Dongzhou Mu’ (The Eastern Zhou Tombs at Changzi County in Shanxi), Kaogu Xuebao 4: 503–29.

So, J.F. 1999. ‘Chu Art: Link Between the Old and the New’, in J.S. Major and C.A. Cook (eds), Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 33–47.

Steiner, D.T. 2001. Images in Mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stewart, A. 1990. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. London and New Haven: Yale University Press.

Summers, D. 2003. Real Spaces: World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism. London: Phaidon.

Tanner, J. and R. Osborne. 2007. ‘Introduction: Art and Agency and Art History’, in R. Osborne and J. Tanner (eds), Art’s Agency and Art History. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 1–27.

Trigger, B. 2003. Understanding Early Civilizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vermeule, E. 1979. Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry. Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Vernant, J-P. 1991. ‘The Birth of Images’, in Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 164–85.

Wesenberg, B. 1992. ‘Mausoleumfries und Meisterforschung’, in K. Zimmermann (ed.), Der Stilbegriff in den Altertumswissenschaften. Rostock: Univ. Institut für Altertumswissenschaften, pp. 167–80.

Wu Hung. 1995. Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

———. 1999. ‘The Art and Architecture of the Warring States Period’, in E.L. Shaughnessy and M. Loewe (eds), The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 651–744.

———. 2005. ‘On Tomb Figurines: The Beginning of a Visual Tradition’, in H. Wu and K.R. Tsiang (eds), Body and Face in Chinese Visual Culture. Harvard East Asian Monographs. Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 13–47.

Yates, R.D.S. 2007. ‘The Rise of Qin and the Military Conquest of the Warring States’, in J. Portal (ed.), The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. London: British Museum Press, pp. 30–57.