CHAPTER 4

THE NETWORK OF STANDARD STOPPAGES (C.1985)*

Alfred Gell

The topic I intend to discuss in this paper is the representation of duration and the problem of continuity in the visual arts, specifically the works of Marcel Duchamp. But before I enlarge on my theme, it may be as well for me to explain why I think it is one which has a certain anthropological relevance, quite apart from general cultural interest.

I have two main arguments to put forward on this score. First of all, the formative period of twentieth-century art (i.e. 1890–1925) coincides exactly with the formative period of our own subject. The intellectual currents which created the distinctively ‘modern’ sensibility in the visual arts were active elsewhere in the domain of culture. Scientists, philosophers and sociologists form a common constituency in modern technological societies, which also includes practitioners and critics of the various arts, and what each does has an impact on what the others are doing.

That this is so is a commonplace enough observation, but it is one to which we pay insufficient heed because of the overriding rigidity of disciplinary boundaries. But if we really want to understand the historical underpinnings of the texts which still form the point of departure for serious theoretical efforts in anthropology – the texts of Durkheim, Mauss, Boas or Malinowski – then it is clearly essential that these texts be understood in the light of the dominant ideas in the cultural field which characterised the epoch in which they came into being.

The significance we should attach to the cultural circumstances which gave rise to anthropology as a distinct subject has been reinforced recently by the growing recognition of the ‘reflexivity’ of anthropological investigations. If it is true, as is now widely accepted, that anthropological work involves a continual interplay between the cultural presuppositions of the anthropologising and anthropologised-upon parties, it is all the more necessary for anthropologists to be aware of the formative influences which have shaped their own cultural experience.

The second reason for making a particular study of the cultural influences at play during the ‘early modernist’ period at the beginning of the present century is that many of the dominant issues which preoccupied both the originators of anthropological theory and the artists and writers who were their contemporaries remain salient issues to this day. We need to continually renew our contact with this formative period, not only because historical study of the origins of anthropological theory is the major source of theoretical renewal in the present, but because, by means of ‘lateral’, rather than narrowly ‘vertical’, excavation of the foundations of anthropology we can come across a variety of illuminating sidelights on many of our most pressing problems.

Such ‘lateral excavations’ are what I intend to undertake here. In particular, I hope to show that Duchamp’s struggle to represent ‘the fourth dimension’ visually involves certain conceptual strategies which are just as applicable in anthropological contexts as they are in pictorial ones. Essentially, Duchamp was concerned to construct a model system for transcending the opposition between the discontinuity of temporal ‘moments’ (and the discontinuity between ‘images’ and/or ‘concepts’ corresponding to moments abstracted from time) and the continuity inherent in temporal duration itself.

We still have the problem. We still continually hear this or that anthropological theory lambasted on the grounds that it ‘cannot handle change’. But where does one look for a coherent account of what might be meant by ‘change’ – as opposed to a rag-bag of historical-particularist accounts of particular states of affairs or ‘situations’ brought about by the operation of particular causative factors at particular times and places? The construction of such historical-particularist accounts of ‘change’ is work of a kind which can most conveniently be left to historiographers.

Anthropologists, red-blooded ones at least, are prone to live more adventurously, in the Badlands which lie beyond History. But this means that anthropologists need to think about societies and cultures, and the ways in which they change/remain the same, in ways which would not occur naturally to historians. The sought-for anthropological account of ‘change’ is not a summation of historical-particularist causal explanations for this-that-or-the-other observed change, but a class of structural models which seek to expose the possibilities and constraints which govern the transformation of elements in structurally integrated systems of relationships forming a totality.

The provision of such systematic models of change neither advances nor impedes the search for particular explanations of particular historical facts. It bypasses, or rather, leap-frogs over, the problem of historical explanation, per se, and focuses attention instead on the phenomenon of change as a problem of order and its transformations; the order that we might otherwise seek in a cycle of myths, the grammar of a language, or – as in this case – the oeuvre of an artist.

The burden of my paper is that the work of Marcel Duchamp can be read as an extended commentary on the problem of temporal order and its transformations; that it advances a certain metaphysic of temporality which is both present – at the level of the microcosm – in the iconography of particular works, and that the same metaphysic of temporal order is present, at the macrocosmic scale, in the structural properties of Duchamp’s oeuvre regarded as a whole. It is therefore highly relevant to the anthropologist for two reasons; firstly because it presents us with an exceptionally coherent and codified instance of the phenomenon of temporal transformation, on which we can try out various modelling strategies, and secondly because, by virtue of certain structural features which I will identify in due course, it points us in a specific direction in the search for solutions.

As I remarked, the historically formative period in the development of modern art coincides with the historically formative years of social anthropology, particularly the heyday of the Année Sociologique. It also coincides with the period during which pragmatism came into existence via the work of William James and George Herbert Mead, and the period of Edmund Husserl’s development of phenomenology. There are numerous interconnexions between these intellectual currents, which I can hardly hope to explore very far in a single paper. James, Mead and Husserl are figures who have had an acknowledged influence on anthropology, and I will show that their ideas are relevant to the art of Marcel Duchamp as well. But it is with another intellectual of the period that I intend to begin the discussion; the rather more shadowy figure of Henri Bergson.

The entire period was one which was dominated by the philosophy of Bergson, a figure much less influential today than any of the ones I have mentioned, but at that time the equivalent of Lévi-Strauss or Chomsky. Bergson’s philosophy, which could be tentatively summed up as anti-rationalist Kantianism, pervades James and Mead, is closely linked to Husserl at certain points (particularly in relation to the problem of temporality) and can also be detected as an essential ingredient of the later Durkheim and Mauss, though it would require a separate paper to demonstrate this fact and its significance.

Bergson’s influence has been often detected in the domain of the arts as well. Proust’s Bergsonism is well documented; ‘Bergsonian’ elements in the Cubism of Picasso and Braque remain conjectural, at least in the eyes of such recent scholars as Linda Henderson, to whom I shall return. Whatever the verdict of historians on the particular problem of ascribing, and documenting, the influence of particular Bergsonian ideas on particular individuals and their works, I think it is anthropologically justifiable to seek in Bergson’s philosophy the ‘Reference Myth’ (myth de réference) of the age. It is in conjunction with, or by contrariety towards, this abstract structure of ideas that the particular developments, in psychology, sociology and the arts, which characterised this period, most coherently form an order. In saying this I do not in the least wish to assert that Bergson is primarily responsible for the ideas which are typical of modernism and in one form or another still survive; indeed Bergson’s limitations as an originator of ideas are sufficiently attested by his subsequent rapid decline in popularity and influence. But Bergson provides the most centrally positioned point of departure for the exploration of the culture of modernism in its nascent stages, and for that reason I will begin with him.

* * *

We can begin with the problem of the relation between Bergson and Cubism which I mentioned a moment ago. The kernel of Bergson’s ideas are contained in his opposition between the discontinuous, artificially stabilised, geometrised, timeless order of conceptual thought, which is essentially oriented towards action and accomplishment, and the continuous, unbounded, malleable, self-transforming order of durée, and the cognitive mode which corresponds to it, which is metaphysics, which tends towards understanding and transcendence, rather than action.

Now art historians have noted that Cubism, despite its geometrical-sounding name, originated in the efforts of Cézanne to overcome the geometrical strait-jacket which had held Western art in its embrace since the time of Giotto. Cézanne shows us cups and saucers whose outline corresponds to what is visible not from one central perspective, but from more than one such perspective. Similarly, comparison of certain of Cézanne’s late landscapes with photographs taken from the points at which the artist is known to have positioned his easel reveal the interesting fact that parts of Mont St Michel are shown which are not actually visible from the painter’s vantage-point, but only from further down the road shown curving away in the foreground. The resultant pictorial effect is that one has a peculiar sense of being drawn into the landscape which, because of its geometrical distortion, compels one to follow the painter’s own trajectory in space in order to reconstitute it coherently.

Cézanne’s limited experiments with what one might call ‘continuous perspective’ are Bergsonian, not because there is much likelihood that Cézanne read Bergson, or that Bergson would have approved of Cézanne (we know for certain that Bergson detested avant-garde art) but that, in response to certain cultural synchronicities, both represent reactions away from 19th-century positivism in the direction of a philosophy of continuity. Exactly the same interpretation (in terms of continuity vs. discontinuity) can be placed on Cézanne’s important dictum that ‘colour modulates form’ (and not outlines and/or shadows) – forms emerge out of a continuous field or colour, rather than being something inherently possessed by isolated ‘objects’ surrounded by ‘empty’ space.

‘Continuous perspective’ and ‘form modulated by colour’ provided the technical basis for the development of Cubism by Braque and Picasso. It is in relation to these artists and the later Cubists such as Metzinger, Gris and Duchamp that the debate about whether Bergson ‘influenced’ Cubism is conducted. From an anthropological point of view it seems to me to be perfectly consistent to deny that Bergson had any direct historical responsibility for the formation of the Cubist style, and simultaneously to affirm that Cubism cannot be understood except in a Bergsonian light. It is the possibility of this apparently self-contradictory position which sets us apart from the historians, and so it is worthwhile examining it in a little more detail.

Certain art historians (e.g. Gray 1953: 87ff.) have noted that passages occur in Bergson which appear, at first sight, like descriptions of Cubist pictures. Thus:

Suppose we wish to portray . . . a living picture . . . [a] way of proceeding is to take a series of snapshots . . . and to throw these instantaneous views on a screen . . . Such is the contrivance of the cinematograph, and such is the nature of our knowledge . . . We take snapshots, as it were, of passing reality; and as these are characteristic of the reality, we only have to string them on a becoming, abstract, uniform, and invisible, situated at the back of the apparatus of knowledge, in order to imitate what there is that is characteristic of this becoming itself. Perception, intellection, and language so proceed in general. (Bergson 1911: 331–32)

If we were to turn at once to some fragmented, multifaceted, Cubist picture, it might indeed seem that an effort had been made to reproduce Bergson’s description of ‘cinematographic perception’. But Gray’s argument is open to certain insuperable objections which have recently been raised by Linda Henderson in a remarkable work on the intellectual sources of modernism (1983). She points out, perfectly correctly, that there are no Bergsonian references in contemporary documentary sources on Cubist aesthetics. This is much less serious, however, than her further objection that the whole point of Bergson’s discussion of ‘cinematic perception’ is to criticise it and to expose its fallacious basis, not to promote it as a model which artists might want to imitate. If what Cubist paintings show us is the fragmentary, discontinuous, world of cinematographic perception, then far from representing the philosophy of continuity, as I am claiming, they are doing precisely the reverse.

And in fact, Cubist theoreticians emphatically rejected a cinematographic reading of their work, emphasising their goal as the unification and universalisation of space and form. But the fact remains that Cubism, as a style, both suggested a cinematographic reading, and signally failed to suggest spatial continuity, for the good reason that efforts to radicalise Cézanne’s rather sly use of multiple perspectives inevitably led to an appearance of fragmentation. Picasso, Braque and Gris simply accepted this state of affairs, and exploited its possibilities: Cubists of a purist stamp, such as Gliezes and Metzinger, tried to overcome it by retreating to a style closer to Cézanne’s.

Bergson’s problem, the problem of continuity, can therefore be justifiably considered to correspond, at a metaphysical level, to the Cubist’s problem of spatial-pictorial continuity. But Bergson could hardly have been a source of encouragement to the Cubists because he strenuously argued that perception, being cinematographic, gives us only discontinuous, partial, transient objects, rather than the plenitude of durée. And contemporary painters, even Cubist painters, were instinctively perceptual realists.

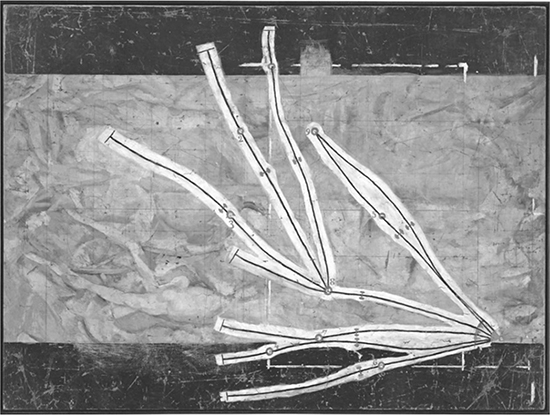

At this point I can introduce Duchamp himself into the discussion. Duchamp became a Cubist in 1911–12, having occupied himself for the previous few years painting a series of symbolist pictures whose predominantly initiatory themes would seem to have been drawn straight from the pages of Van Gennep (another of those cultural synchronicities it would be so interesting to explore). In 1912, Duchamp painted the notorious picture Nude Descending a Staircase (Figure 4.1) which resulted in him being officially expelled from the Cubist movement, whose adherents excluded him thereafter from their exhibitions. His crime? Cinematism. Nude Descending a Staircase affronted the ‘pure’ Cubists because it revealed frankly what official Cubism denied, viz. that the unification of space was accomplished in time, and that the representation of this unification was inevitably cinematographic in character while any pretence at perceptual realism was being maintained. Nude Descending a Staircase was an Awful Warning to the effect that Bergson’s strictures on the attempt to provide a spatial image of durée were inexorable.

Duchamp was excluded because he was a futurist deviationist, i.e. he appeared to be embracing the futurist view, promulgated by Boccioni, an open and explicit Bergsonian, that the ‘fourth dimension’ (the Cubists’ Holy Grail) was time. But Duchamp’s crime was probably not so much his futurist deviationism as his dangerous propensity for mockery and irony, which sorted ill with the ultra-serious Cubist collective image. Duchamp was the first artist to have attempted to paint humorous works in the Cubist style; the Nude Descending a Staircase is such a one; Dulcinea (1912), which brings us closer to the main theme of this paper, is another outstanding example.

4.1 Duchamp, Marcel (1887–1968). Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, oil on canvas, 1912. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA / The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950 / The Bridgeman Art Library. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2012.

We see a woman pursuing a rotary course through the picture space, becoming progressively divested of her clothes as she does so. To the element of cinematism is added an element of striptease, reminding us that the first sketches of Duchamp’s masterpiece The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors, Even, eventually completed in 1923, lie only a year or so away in the future. It is this element of playful sarcasm – the ‘stripping’ of ‘Dulcinea’ is simultaneously a ‘stripping’ of her inherently lustful attitude of the painter and spectator towards the female model – which should alert us to the possibility of taking a third view of the relations between Bergsonism and Cubism more nuanced than either the Gray view that Bergson ‘influenced’ Cubism, and the Henderson view that he did no such thing. Duchamp was likely to have been acquainted with Bergson’s ideas, since he was an up-to-date intellectual of the period. And it is surely plausible to suggest that Duchamp painted these pictures precisely to demonstrate the nullity of the Cubist search for the unifying ‘fourth dimension’ in the pictorial language that he was later to dismiss as belonging to ‘retinal’ art, and its inevitable degeneration into fragmentation and cinematism, despite earnest intentions to the contrary. These pictures are brilliant satires on the Cubist style he was to abandon immediately upon completing them.

But these mocking farewells to Cubism, delivered with such panache, did not mean that Duchamp could escape from the essential Bergsonian problem which the Cubists had so signally failed to resolve. Henderson shows how he continued to wrestle with the problem, transferring it to a level of symbolic evocation, rather than persisting in doomed efforts to represent the unrepresentable. The iconographic analysis of Duchamp’s output, from this point onwards, consists of tracing his unremitting pursuit of the Cheshire-cat-like ‘fourth dimension’, which comes to stand both for a kind of mythologised realm, an echo of the fourth-dimensional fantasies of Hinton, Ouspenski and Pawlovski, and at other times a mathematical theorem conjured from the rather obdurate pages of Poincaré and Jouffret.

The mockery at the Cubists’ expense which I have just identified in connection with the Nude Descending a Staircase and Dulcinea has a serious point to it; namely, that it implies a recognition of the intractability of the problem of continuity. We see (if we are so lucky, otherwise we imagine) nudes walking down staircases, a complete, continuous movement which unfolds in a vivid present and shades into a proximate past and future: but should we attempt to intellectually reconstruct that seeing, either in language or in visual representations, we are not able to greatly improve on the stilted and irredeemably immobile freeze-frame sequences of Marey or Muybridge. Bergson’s opinion was that only the articulation of cinematographic perception with our own interior durée, whose spontaneity mirrors the evolving and self-transforming durée of the cosmos, enables these frozen perceptions to come to life. But in proposing this solution, Bergson was voicing a trend in philosophical thought which had both more down-to-earth exponents, of whom the most important and engaging was William James, and also more subtle ones, notably Husserl, whose account of temporal continuity I will expand at a later stage. All three philosophers (James, Bergson and Husserl) approached the topic of time with the problem of continuity and discontinuity uppermost in their minds. In fact, continuity is an ancient problem in this branch of philosophy with a history which stretches back at least as far as the paradoxes of Zeno.

In the ninth chapter of Principles of Psychology, William James (1890) explores the basis of the continuity inherent in any sequence of mental experiences over time, a continuity which constantly seems to be denied in the language we are obliged to employ when we attempt to describe our mental life; language which divides up the continuous stream of consciousness into a discontinuous succession of separate ‘thoughts’, ‘impressions’, ‘sensations’, and so on. How is the instantaneousness of this present moment-in-being, and the fixity of this impression, image or sensation, to be reconciled with the fact that we retain a sense of continuity over time in the succession of our mental states, so that each one flows into the next without perceptible transitions?

In responding to this question as a strictly psychological problem, James introduces his notion of the ‘specious present’, an expanded present centred on the moment-in-being but surrounded with a ‘fringe’ of pastness and presentness. Successive mental states are compared to a series of overlapping waves, whose peaks correspond to particular impressions, and whose ascending and descending slopes correspond to the coming-into-awareness and dying-away of successive impressions. The declining slope of the preceding wave of consciousness in a series overlaps the ascending slope of the next succeeding wave, and so on for the next, and the next.

James continues:

As we take, in fact, a general view of the wonderful stream of our consciousness, what strikes us first is this different pace of its parts. Like a bird’s life, it seems to be made of an alteration of flights and perchings . . . The resting places are usually occupied by sensorial imaginings of some sort, whose peculiarity is that they can be held before the mind for an indefinite time, and contemplated without changing; the places of flight are filled with thoughts of relations, static or dynamic, that for the most part obtain between the matters contemplated in the periods of comparative rest.

Let us call the resting places the ‘substantive parts’ and the places of flight the ‘transitive parts’ of thought. (James 1890: 158)

Now that rings a bell of some sort, does it not, fellow anthropologists? You are right; this is the Dakota wise man, cited by Durkheim and later by Lévi-Strauss, in his brilliant discussion of Bergson in the final chapter of Totemism (1962). Here are the two texts so startlingly brought together there by Lévi-Strauss:

Everything as it moves, here and there, makes stops. The bird as it flies stops in one place to make its nest, and in another to rest in its flight. A man when he goes forth stops when he wills. So the God has stopped. The sun, which is so bright and beautiful, is one place where he has stopped. The moon, the stars, the winds, he has been with. The trees, the animals, are all where he has stopped, and the Indian thinks of these places and sends his prayers there to reach the place where God has stopped and win help and a blessing. (Dorsey 1894, cited in Lévi-Strauss 1964: 98)

And Bergson:

A great current of creative energy gushes forth through matter, to obtain from it what it can. At most points it is stopped; these stops are transmuted, in our eyes, into the appearance of so many living species, that is, organisms in which our perception, being essentially analytic and synthetic, distinguishes a multitude of elements combining to fulfil a multitude of functions; but the process of organisation was only the stop itself, a simple act analogous to the impress of a foot which simultaneously causes thousands of grains of sand to contrive to form a pattern. (Bergson 1958: 221, cited in ibid.)

The common theme of these three texts is that they all express what one may call the philosophy of continuity, and deny that the discontinuities experienced as ‘stops’ or ‘perchings’ have ontological self-sufficiency. Now let us turn to a painting Duchamp produced in his post-Cubist phase, having, as we have seen, become disillusioned with the Cubists’ efforts to suggest the continuity of the fourth dimension by multiplying perspectives indefinitely.

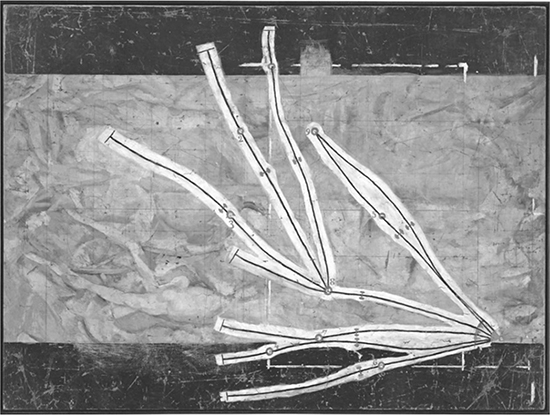

This painting, produced in 1914, is called Network of Stoppages (Figure 4.2) and is a preparatory study for The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors, Even (1923, hereafter referred to, more conveniently, as the Large Glass). In form, it resembles, and is I think supposed to resemble, a map, perhaps of a railway system (this is suggested by the symbols used to indicate the termini and stations). This ‘network’ viewed in perspective, becomes the network of capillary tubes which draw off the ‘illuminating’ gas from the bottle-like homunculi in the ‘cemetery of uniforms and liveries’ (1913) and transmit it to the sieves, where it will be frozen and turned into spangles, before continuing its onward progress towards the bridal domain, at the top of the picture. The ‘Standard Stoppages’ referred to in the title of the picture have a dual meaning. We can understand them to be the stops or stations on the railway-like network indicated by circles and numbers in Figure 4.2, but the reference is also to the three wooden templates which Duchamp created as a separate work (The Three Standard Stops of 1913–14), and which he used to draw the curves in the Network. These templates are called ‘standard stops’ for the following reason. Duchamp, like Bergson, was interested in the relationship between randomness, or chance, and order. He had the very Bergsonian idea that disorder, seen from another point of view, is order, and vice versa. Consequently he pioneered the introduction of aleatory techniques into painting – random elements which by their very disorder evoke the possibility of a higher order (in the fourth dimension, of course). The three standard stops were created by taking one-metre lengths of string and dropping them one metre onto canvas smeared with sticky paint. These ‘random’ curves were to become the standard straight lines and measures of spatial dimensions in the non-Euclidean geometry of the fourth dimension. Wooden templates were made to the pattern of the three curved lengths of string, and these Duchamp used to trace out the lines in the network. Hence not only the ‘stations’ on the network are stoppages, but the lines themselves, because they show where the string, randomly twisting in its fall, stopped, once it hit the canvas. They are, as Duchamp says, ‘canned,’ or ‘frozen’ chance. What is suggested here is both the non-Euclidean geometry of the fourth dimension, in which these ‘non-standard’ curves and lengths are as ‘standard’ as our straight lines and metre measures, and also the idea that any ‘stop’, any ‘freezing’ of the random pulsations which pervade the universe, is essentially arbitrary, as arbitrary as the curves traced by falling string. This is all exceedingly like Bergson, who emphasises again and again the arbitrariness of our prison of fixed concepts, in the face of the continuous creative evolution of the universe itself, the élan vital which flows through all forms, and which only seems to come to rest, but never does in reality.

4.2 Duchamp, Marcel (1887–1968). Network of Stoppages, 1914. New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Oil and pencil on canvas, 58 5/8’ × 65 5/8’ (148.9 × 197.7 cm). Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund and gift of Mrs William Sisler. 390.1970 © 2012. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence.

But interesting though all this is, we have not yet touched on the most significant aspect of the Network, the feature which most brings out the philosophical subtlety of which Duchamp is always capable, even in his most casual productions. There is something peculiar, you will notice, about the background on which the network is projected. This background consists, in fact, of two other paintings superimposed on one another, so that counting the network itself, on top, we have a total of three superimposed paintings. The base of the painting consists of a large version of Duchamp’s first major work, completed in 1911, Young Man and a Girl in Spring. This painting, using a quite different (post-impressionist) stylistic language, anticipates may of the themes found in the Large Glass. On top of this has been placed a transparent ground, and onto this has been transferred a squared-up sketch Duchamp made at the beginning of 1913 for the general layout of the Large Glass at a time when the precise arrangement of the Bachelor Domain had not yet been worked out. And on top of this Duchamp places the Network of Stoppages which will, in turn, become the network of capillary tubes leading from the ‘cemetery of uniforms and liveries’ to the ‘sieves’ in the completed Large Glass. So to the three superimposed paintings that we can actually see, we should add a fourth, the as-yet-unbegun painting on glass for which this is a preparatory study, and without which this painting cannot be understood.

If we pause at this point and recall the passages cited above, particularly James and Bergson, we can perhaps agree that this painting is ‘saying’ very much the same kind of thing, in a visual way. The superimposed paintings correspond to what James called, in the passage I have cited, the ‘substantive parts of thought’, while the conceptual spaces which separate the paintings, the dimension in which they are separated, corresponds to the ‘transitory parts of thought’ and may indeed be identified with the fourth dimension, both in its ordinary temporal sense and also in its occult one.

* * *

This is the third meaning which we can attach to the mysterious title, the Network of Stoppages. It implies that each painting, each phase in the construction, through many preliminary studies, of a major work such as the Large Glass – which itself can be seen as a ‘study’ for Duchamp’s final masterpiece Given the Waterfall and the Illuminating Gas (1948) – can be seen as a ‘stop’. In fact, Duchamp’s subtitle for The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors, Even is, appropriately enough, A Delay in Glass. It is as if the forms we see in this painting have been temporarily captured and stabilised in their glassy medium like very long-delayed insects trapped in amber, which might still resume their flight one day.

In the Network of Stoppages, then, we are able to see Duchamp’s modus operandi as a painter laid bare in a particularly perspicuous fashion, and we can begin to grasp its philosophical meaning. This method is the serial concealment of images behind other images, concealment which, as in occult art generally, serves as a device for oblique revelation of the unrepresentable. Duchamp’s transparent paintings are descendents of the transparent clouds which Hermes, on the extreme left of Botticelli’s Primavera, is stirring with his wand; clouds which stand, according to Edgar Wind (1958), for the screen of imagery which has to be interposed between mortal vision and the ultimate revelation of the neoplatonic mysteries.

But here I will not concern myself particularly with the details of Duchamp’s occult system, not least because a copious body of exegetical commentary already exists in the writings of Schwarz, Lebel, Paz, Clair, Henderson etc. (If Duchamp is not the most widely known twentieth-century artist, he is certainly the most written-about.) The method of superimposition of images, of revelation-by-concealment, can be discussed in a more or less non-occult frame of reference as a device for representing the fourth dimension in its more mundane sense, i.e. Bergsonian durée, or continuity.

Let us begin by noting that the Network of Stoppages can be read as painterly autobiography. We are presented with a sequence of four images. The first, which is almost obliterated, is a ‘recollection’ of Duchamp’s phase as a latter-day symbolist, the phase in his career in which he produced a series of pictures showing scenes with vaguely ritual, initiatory connotations (The Bush, Baptism, Young Man and a Girl in Spring of 1909–10). Over this is placed a screen-like ground, on which is placed a preparatory sketch of the composition of The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors, Even – a composition which Duchamp finalised in advance of the idea, which came to the painter at about the time he was working on the Network of Stoppages, of executing the eventual painting on sheets of glass. (We may even hypothesize that the possibility of a glass painting was suggested to him in the course of completing this very picture, in which paintings are seen through other paintings.) Finally, over the compositional sketch, is placed the Network itself, which, as we have seen, is both a development of a previous work (the assemblage of templates known as the Three Standard Stoppages) and a stage in the design process for an element in the Bachelor Apparatus (the Network, viewed in perspective, becomes the Capillary Tubes in the final work).

It is perhaps misleading, though, to think of this as autobiography, since an autobiography is written as a narrative after the facts, representing the past as a whole made up of completed events; the temporal perspective in the Network runs equally, and perhaps predominantly, in the other direction, representing the future seen from its past as much as the past seen from its future. The past is progressively obliterated by successive layers, layers which, while effacing the past, adumbrate their own future. What we have, therefore, is not a narrative recreated post festum, but a glimpse of the temporal structure of Duchamp’s ‘specious present’ in which successive ‘stops’ (in a temporal series embracing past, present and future simultaneously) interact in a complex relational network. This relational texture is ‘the fourth dimension’.

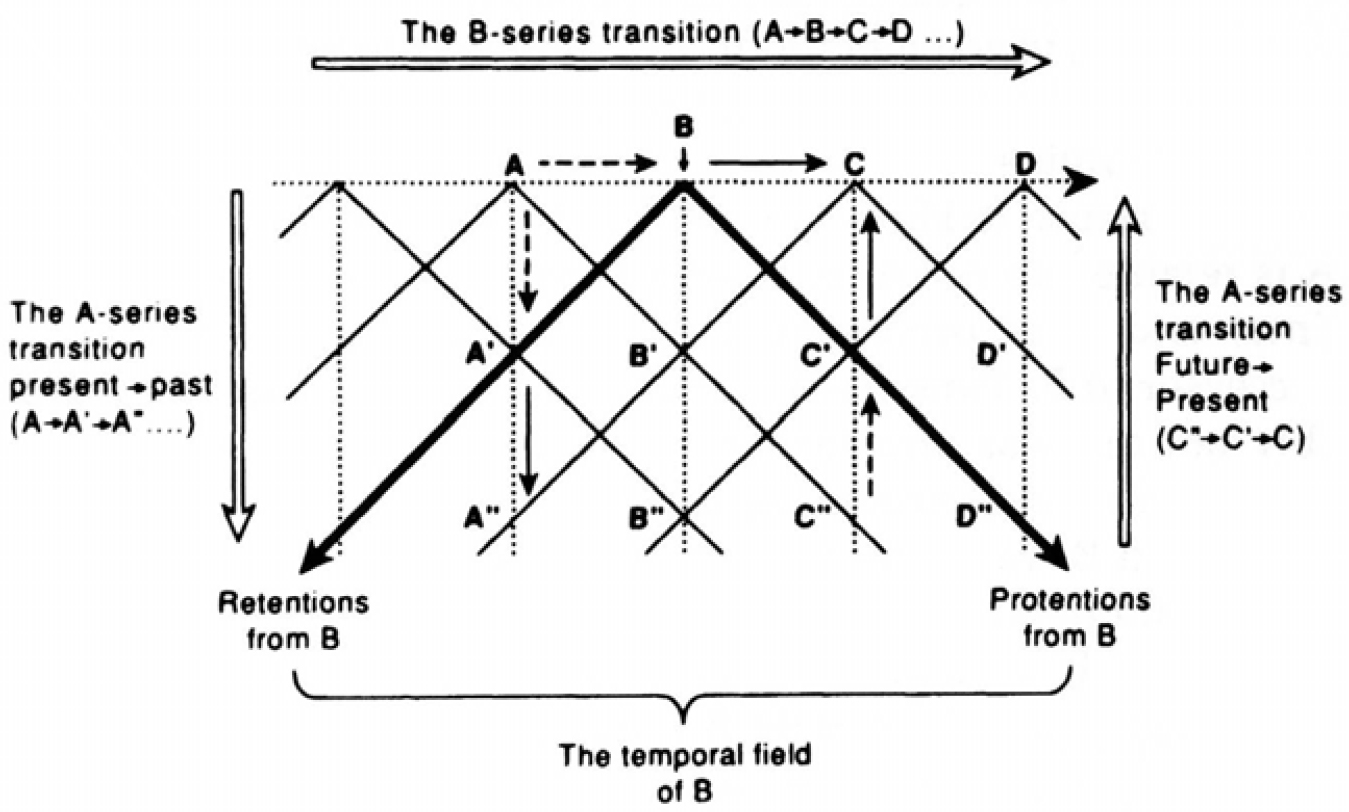

In order to clarify this notion, we need a formal model of the structure of such a temporal-relational network, of the kind hinted at in the painting under discussion. Here, as promised, I will introduce Husserl’s model of internal time-consciousness of 1901, itself a development of the earlier treatment of the subject by William James, and perhaps also influenced by Bergson.

Husserl’s problem, inherited from his teacher, the introspective psychologist and proto-phenomenologist, Franz Brentano, was the basic problem of continuity and discontinuity in subjective time- consciousness.

* * *

Brentano was interested in the problem of the continuity of the subjective/perceptual ‘present’ given the conventional idea that the present is a knife-edge between the future and the past. Brentano asked how we are able to hear a continuous tone, an A played on the oboe lasting five seconds, as a continuous duration. By the time we are into the fourth second’s-worth, the first second’s-worth is no longer present, and no longer audible, but perceptually speaking it is still a component of the tone we are hearing in the present. Brentano supposes that we hear only the now-present tone, but that we enrich this hearing with ‘associations’ derived from earlier hearing-experiences in the sequence. We make, he says, a ‘primordial association’ (Husserl 1964: 33) between the tone we are currently hearing and what we are able to reproduce in phantasy of what we have just heard. In other words Brentano has a model based on short-term memory: ‘hearing a continuous tone’ consists of forming associations between auditory input and inputs replayed from short-term memory. The recent past is ‘fed forward’ (to use the terminology of cybernetics) and matched against present input: if there is a match, then there is a perception of a temporally continuous ‘time-object’ (a tone which endures).

Husserl’s views are cognate with those of his predecessor, but he introduces some additional distinctions, needed in order to overcome the difficulty posed by the fact that we can distinguish clearly between ‘remembering’ the experience of hearing an A played on the oboe, as a time-consuming event which took place in the past, and the kind of feed-forward from the recent past which is involved in generating the impression of continuity in the present. Brentano’s solution to the continuity problem will not work if the ‘primordial association’ between the first second’s-worth of the A-tone and the fourth requires us to relive the first second’s-worth as a phantasied ‘present moment’ concurrently with experiencing the fourth second’s-worth of the tone in the real present; because this means that there are a multiplicity of ‘now’ moments (associated with one another, but distinct) rather than just one ‘now’ which extends into the past and is open towards the future. The effect is a fragmentation of ‘nows’ like individual frames of a cine-film, with associative relationships between them. Husserl overcomes this problem by distinguishing between ‘retentions’ of experiences and ‘reproductions’ of experiences. ‘Retentions’ (contrasting with both perception and memories) are what we have of temporally removed parts of experiences from the standpoint of the ‘now’ moment; ‘reproductions’ are action-replays of past experiences of events carried out from the standpoint of a remembered or reconstructed ‘now’ in the past.

Husserl treats ‘retention’ and its future-oriented counterpart ‘protention’ not as phantasied memories or anticipations of other ‘nows’ associated with the present ‘now’ but as horizons of a temporally extended present. In other words, he abandons the idea of a knife-edge present, a limit – itself without duration – between past duration and future duration. The ‘limit’ remains as the ‘now’-moment, but the ‘now’ and the ‘present’ can be distinguished. The present has its own thickness and temporal spread. Listening to the final second’s-worth of the five-second A tone, I do not ‘remember’ (reproduce) the first second’s-worth; I am aware only of a single tone which prolongs itself within a single present moment which includes the whole of the tone, but within which this tone is subjected to a continuous series of ‘modifications’ brought about by a series of shifts of temporal perspective as the present unfolds and transforms itself.

Husserl’s distinction between retention and reproduction makes it possible to conceptualise the way in which temporal experience coheres from the standpoint of the present: ‘retentional awareness’ is the perspective view we have of past phases of an experience from the vantage-point of a ‘now’ moment which slips forwards, and in relation to which past phases of our experience of the present are shoved inexorably back. Reproduction of some recollected event, by contrast, involves the temporary abandonment of the current ‘now’ as the focal point around which retentional perspectives cohere, in favour of a phantasied ‘now’ in the past which we take up in order to replay events mentally.

Retentions, unlike reproductions, are all part of current consciousness of the present, but they are subject to distortion or diminution as they are shoved back towards the fringes of our current awareness of our surroundings. We also have ‘perspective’ views of future phases of current events as they emerge out of the proximate future, and Husserl likewise suggests that we should distinguish between those future events which are seen as continuations of the present, versus future events which we reproduce from a standpoint of a phantasied future present. The perspective views we have of the proximate future Husserl names ‘protentions’.

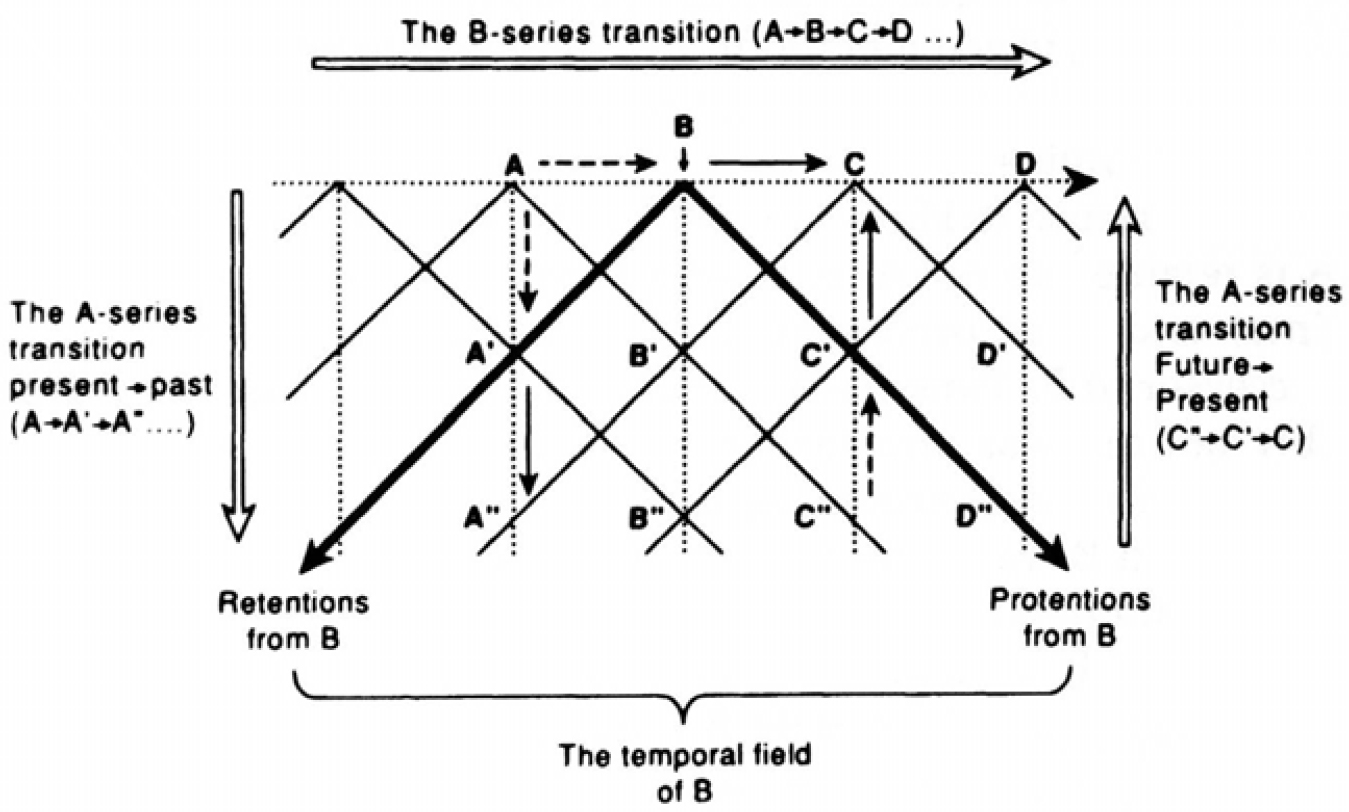

In order to expound his ideas, Husserl makes use of a diagram, of which Figure 4.3 is a version. The horizontal line A B

B C

C D corresponds to the succession of now-moments strung out between the past and the future. Suppose we are at B. The temporal landscape at B consists of the now-present perceptual experience of the state of affairs at B plus retentions of A, as A′, sinking down to the past. A′ is a ‘modification’ of the original A – it is what A looks like from B, i.e. attenuated or diminished, but still present. Perhaps one can think of the ‘modification’ of A as it sinks down into the past (A

D corresponds to the succession of now-moments strung out between the past and the future. Suppose we are at B. The temporal landscape at B consists of the now-present perceptual experience of the state of affairs at B plus retentions of A, as A′, sinking down to the past. A′ is a ‘modification’ of the original A – it is what A looks like from B, i.e. attenuated or diminished, but still present. Perhaps one can think of the ‘modification’ of A as it sinks down into the past (A A′

A′ A″) as a gradual loss of verisimilitude affecting the perceptual judgements entertained at B, C, D, etc. Our perceptual judgements at A do not become inapplicable immediately by virtue of the passage of time, but only gradually, because the world does not change all at once and in all respects. We can no longer, at B, say that the state of affairs at A is ‘now’ the case, because of the change of the temporal index; but many of the features of A have counterparts at B. The fading out of the background of the proximate past as successively weaker retentions (A′

A″) as a gradual loss of verisimilitude affecting the perceptual judgements entertained at B, C, D, etc. Our perceptual judgements at A do not become inapplicable immediately by virtue of the passage of time, but only gradually, because the world does not change all at once and in all respects. We can no longer, at B, say that the state of affairs at A is ‘now’ the case, because of the change of the temporal index; but many of the features of A have counterparts at B. The fading out of the background of the proximate past as successively weaker retentions (A′ A″

A″ A′″. . .) corresponds to the increasing divergence of perceptual judgements entertained at A and judgements entertainable at increasingly distant points in the succession of ‘now’ moments (A′/B, A″/C, A′″/D, etc.). But out-of-date perceptual judgements are still salient because it is only in the light of these divergences between out-of-date beliefs and current beliefs that we can grasp the direction which the events surrounding us are taking, thereby enabling us to form protentions towards the future phases of the current state of affairs.

A′″. . .) corresponds to the increasing divergence of perceptual judgements entertained at A and judgements entertainable at increasingly distant points in the succession of ‘now’ moments (A′/B, A″/C, A′″/D, etc.). But out-of-date perceptual judgements are still salient because it is only in the light of these divergences between out-of-date beliefs and current beliefs that we can grasp the direction which the events surrounding us are taking, thereby enabling us to form protentions towards the future phases of the current state of affairs.

4.3 Alfred Gell, model of Husserl’s internal time-consciousness. From Gell 1992: 225. © Alfred Gell, 1992, The Anthropology of Time and Berg Publishers, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc.

Retentions can thus be construed as the background of out-of-date perceptual judgements against which more up-to-date perceptual judgements are projected, and significant trends and changes are calibrated. As perceptual judgements become more seriously out of date they diminish in salience and are lost to view. We thus perceive the present not as a knife-edge ‘now’ but as a temporally extended field within which trends emerge out of the patterns we discern in the successive updatings of perceptual judgements relating to the proximate past, the next most proximate past, and the next, and so on. This trend is projected into the future in the form of protentions, i.e. anticipations of the pattern of updating of current perceptual beliefs which will be necessitated in the proximate future, the next most proximate future, and the next, in a manner symmetric with the past, but in inverse temporal order.

At B, A is retained as A′ (A′ is A seen through a certain thickness of time) and C is protended as C′, the favoured candidate as successor to B. Time passes, and C′ comes about as C (presumably not quite as anticipated, but approximately so). B is now retained in consciousness as B′, related to (current) C as A′ was to B when B was current. But how is A related to C? From the standpoint of C, A is no longer retained as A′, because this is to put A′ and B′ on a par with one another, and fails to reflect the fact that when B (currently B′) was current, A was even then only a retention (A′). Consequently, from the standpoint of C, A has to be retained as a retention of A′, which is itself a retention of A: i.e. as A’’. This can be expressed more clearly, perhaps, by using brackets instead of dashes. Thus: A (A)B

(A)B ((A)B)C

((A)B)C (((A)B)C)D

(((A)B)C)D etc. where brackets mean ‘retention’, double brackets ‘retention of a retention’, triple brackets ‘retention of a retention of a retention’ and so on.

etc. where brackets mean ‘retention’, double brackets ‘retention of a retention’, triple brackets ‘retention of a retention of a retention’ and so on.

Husserl says that as A sinks to A′ at B, A″ at C, A′″ at D and so on, A becomes a retention, then a retention of a retention, then a retention of a retention of a retention and so on, until reaching the stage of final attenuation and sinking beneath the temporal horizon. The effect of this argument is to abolish the hard-and-fast distinction, still apparent in Brentano’s argument, between the dynamic present and the fixed and unchanging past. Past, present and future are all of a piece, and all equally dynamic in the Husserl model, because any modification, anywhere in the system, sets up correlative modifications everywhere else in the system. Thus the modification in the present which converts C into C′ automatically entrains corresponding modifications everywhere (B′ B″, A″

B″, A″ A′″, D′

A′″, D′ D, etc.). ‘The whole past sinks in a mass, taking all its arranged contents with it’ (Findlay 1975: 11). But the past does not just sink as the present progresses; it changes its significance, is evaluated in different ways, and sets up different patterns of protentions, according to the way in which the present evolves.

D, etc.). ‘The whole past sinks in a mass, taking all its arranged contents with it’ (Findlay 1975: 11). But the past does not just sink as the present progresses; it changes its significance, is evaluated in different ways, and sets up different patterns of protentions, according to the way in which the present evolves.

This dynamic past, and the future which continually alters in its complexion, cannot be accommodated in strictly physical time, because from the point of view of physical time both the past and the future are unalterable. But in providing his model of retentions, protentions and modifications, Husserl is not describing an arcane physical process which occurs to events as they loom out of the future, actualise themselves in the preset, and sink into the past, but is describing the changing spectrum of intentionalities linking the experiencing subject and the present-focused world which he experiences. ‘Modification’ is not a change in A itself, but a change in our view of A as the result of subsequent accretions of experience. It is only in consciousness that the past is modifiable, not in reality and not according to the logic of ‘real’ time: but that this modification takes place is undeniable.

Husserl summarises his view of internal time consciousness in the following passage:

Each actual ‘now’ of consciousness is subject to the law of modification. It changes into the retention of a retention, and does so continuously. There accordingly arises a regular continuum of retentions such that every later point is the retention of every earlier one. Each retention is already a continuum. A tone begins and goes on steadily: its now-phase turns into a was-phase, and our impressional consciousness flows over into an ever new retentional consciousness. Going down the stream, we encounter a continuous series of retentions harking back to the starting point . . . to each of such retentions a continuum of retentional modifications is added, and this continuum is itself a point in the actuality which is being retentionally projected . . . each retention is intrinsically a continuous modification, which so to speak carries its heritage of its past within itself. It is not merely the case that, going downstream, each earlier retention is replace by a new one. Each later retention is not merely a continuous modification stemming from an original impression: it is also a continuous modification of all previous modifications of the same starting-point. (Husserl 1928: 390, cited in Findlay 1975: 10)

If I have understood Husserl correctly, I think that one can treat the horizontal axis of the diagram as representing the sequence of dated events or states-of-affairs in physical time (A B

B C

C D . . .) and the vertical axes as the ‘changes’ in events as they acquire and lose tense-characteristics of futurity/presentness/pastness in psychological time (A

D . . .) and the vertical axes as the ‘changes’ in events as they acquire and lose tense-characteristics of futurity/presentness/pastness in psychological time (A A′

A′ A″

A″ A′″ . . .). From the perspective of physical time, events do not change; they are changes: but from the perspective of psychological time events do undergo a kind of change, just as our view of a landscape changes as we move about in it, and observe it from different angles.

A′″ . . .). From the perspective of physical time, events do not change; they are changes: but from the perspective of psychological time events do undergo a kind of change, just as our view of a landscape changes as we move about in it, and observe it from different angles.

Future events, likewise, do not really change as a result of the fact that, from our point of view, they are becoming less indefinite, more imminent, and can be anticipated with increasing degrees of precision as they approach. But we have a strong compulsion to view them in such a light. Husserl’s model treats this via a continuum of continuums of protentional modifications. Protentions are continuations of the present in the light of the kind of temporal whole the present seems to belong to. ‘To be aware of a developing whole incompletely, and as it develops, is yet always to be aware of it as a whole: what is not yet written in, is written in as yet to be written in’ (Findlay 1975: 8). Protentions are not anticipations of other present moments-in-being, but projections of the subsequent evolution of this one. As such, protentions may be disappointed or decisively fulfilled as the present evolves. It makes a great difference to the evaluation of an event or state of affairs if it was protended in a way highly at variance or not at all at variance to the way in which it actually occurs. Thus if C′ (future) protended from B is very different from C as it actually occurs, that will make a difference to the way in which C′ (past) is retained subsequently at D. The way an event was anticipated as a future event (or not anticipated) makes a difference to the way in which that event is integrated into the past.

* * *

One feature of the Husserl protentional-retentional model deserves additional comment. Although it is put forward in relation to internal-time consciousness implicitly in relation to short durations and moment-to-moment psychological processes, there is no reason to think that the same model cannot serve as a representation of the subjective aspect of temporal processes of longer durations, up to the span of an entire lifetime, or longer if we include the vicarious past and future which historical consciousness provides us with. The Husserl model furnishes us with an instrument of great subtlety for handling the conceptual problems of continuity and change in relation to historical and sociological processes, as well as psychological ones; in this guise it reappears frequently in the writings of Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and Bourdieu, among others.

The painting the Network of Stoppages, which we have been examining, shows us a protentional-retentional field on a scale of a few years, between, say, 1910 and 1918, focused on the ‘now’ moment of the actual making of the image in 1914. We may confidently assume that it was created in entire ignorance of the actual written texts of Husserl, but at the same time the convergence between the structural features of Duchamp’s pictorial technique of superimposed images and Husserl’s model of a continuum of ‘superimposed’ continuums seems to testify to the operation of forces other than sheer contingency.

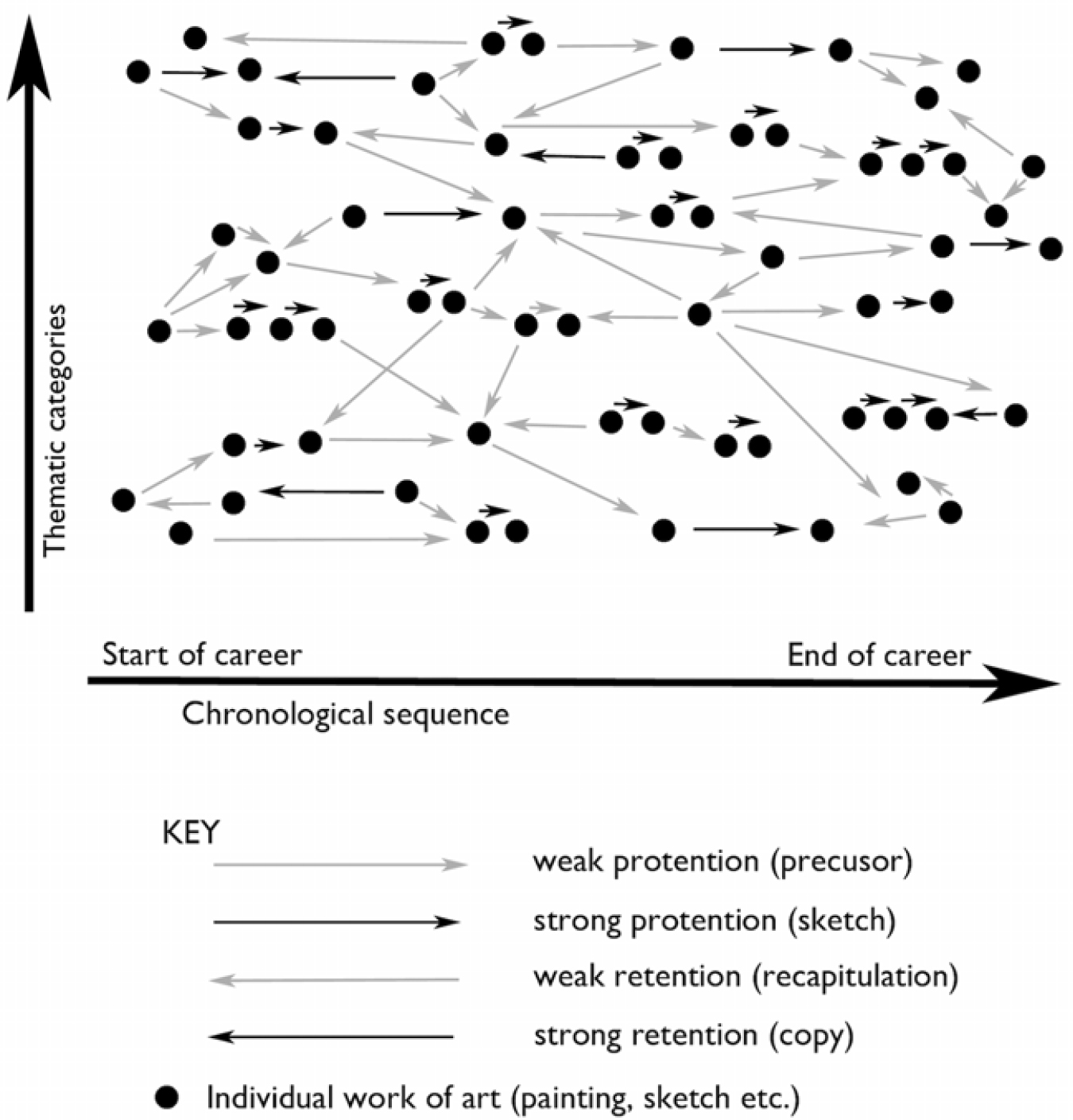

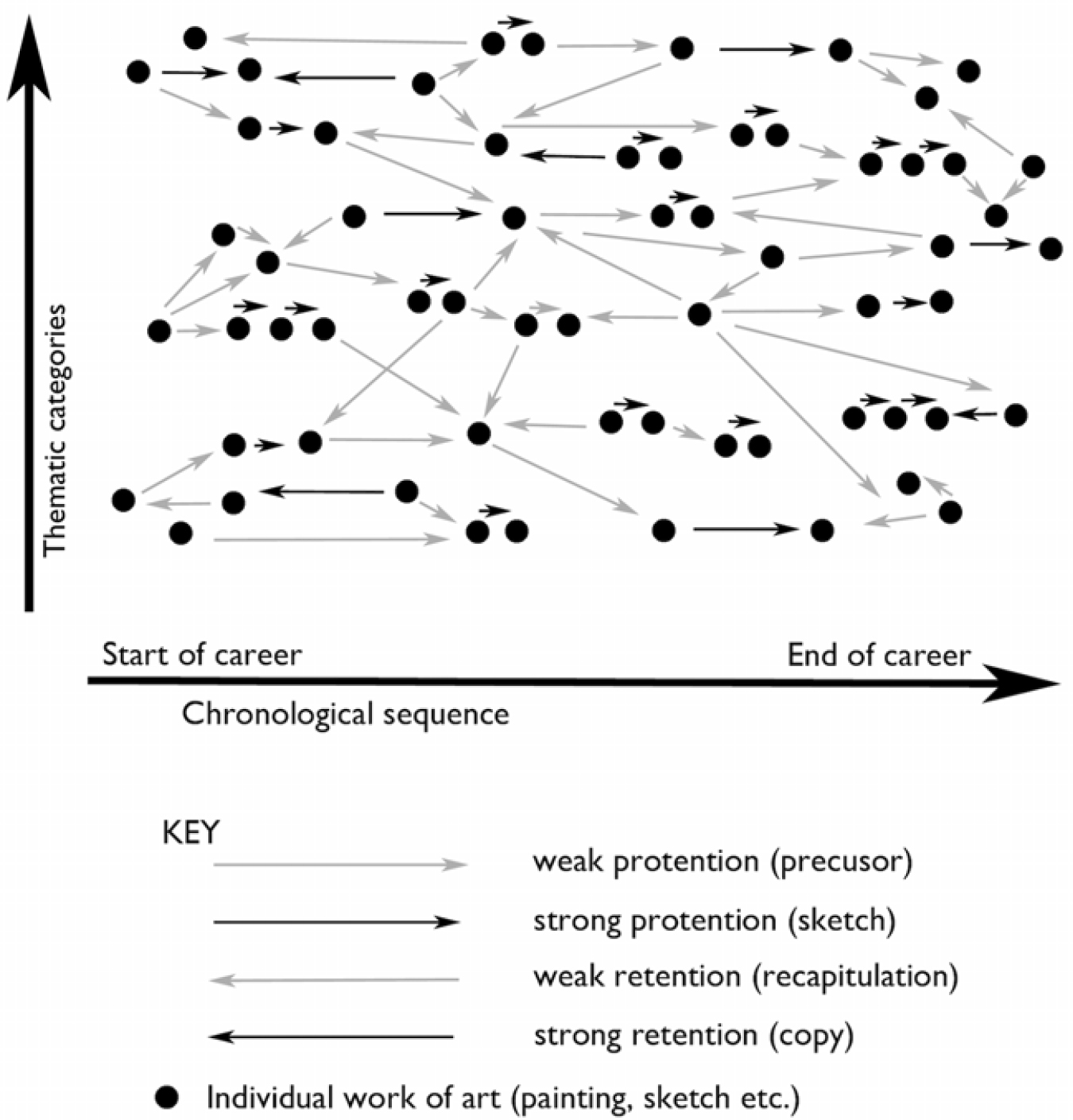

What I want to do now is to establish that the method of superimposition, clearly indicated in this painting of Duchamp’s, is in fact the method which is characteristic of his artistic production as a whole. To this end I have constructed a model of the total output of Duchamp throughout his career, based on the illustrated Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp published by Arturo Schwarz (1969), with the active collaboration of the artist himself (see Figure 4.4).1 It is not necessary for the argument that this figure be examined in much detail, since the general gestalt properties of the figure are what is important, but I should explain at least the basis on which it is constructed. Along the bottom margin are numbers 1 to 416 which correspond to opus numbers in the chronologically arranged Schwarz catalogue, from the earliest sketches of Duchamp’s family members of 1904 (Schwarz 1–20) to the last work Anaglyphic Chimneys (Schwarz 416) of 1966, the year of the artist’s death. Down the left-hand margin, I have listed twenty-five categories corresponding to major thematic ideas which occur repetitively, in various guises, in different works created at different periods in Duchamp’s productive career. A solid dot placed at coordinates which are the product of a vertical axis (opus number = chronological position in the total series) plus a horizontal axis (thematic category) corresponds to each work in the catalogue. However, there are certain works which combine complete representations drawn from more than one thematic category; such works are indicated on the diagram by two or more dots, vertically positioned, with a double-headed solid arrow linking them. Two outstanding examples of such portmanteau works can be pointed out immediately; they are Schwarz 276 (the Large Glass itself, finally completed in 1923) and Schwarz 392 Given the Waterfall and the Illuminating Gas (completed in 1966).

4.4 Alfred Gell, The artist’s oeuvre as a temporal-relational diagram. After Gell 1998: 235.

Between the dots corresponding to specific works or parts of works, I have indicated, by means of single-headed arrows, four kinds of longitudinal relations between works. A solid, backward-pointing arrow (A B) indicates that B is a copy of A, i.e. B is a later work which substantially reproduces the actual visual appearance of A, when there is no reason to think that A was produced in order to serve as a ‘project’ (a preliminary sketch) for B.

B) indicates that B is a copy of A, i.e. B is a later work which substantially reproduces the actual visual appearance of A, when there is no reason to think that A was produced in order to serve as a ‘project’ (a preliminary sketch) for B.

We indicate the latter type of relation, where A (the ‘project’) is produced in order that it should be reproduced at B (perhaps as part of a larger work) by a solid forward-pointing arrow (A B). The solid arrows, therefore, indicate relations which can be called, following Husserl’s terminology, ‘reproductions’ – i.e. they are recapitulations of images, as completed wholes, at different time-coordinates. Copies are like ‘memories’ in the sense of inward action-replays of past experiences; ‘projects’ are, likewise, ‘replays’ of images which are still to be achieved in their final form at some future date, conducted in the present. They are, to use the terms adopted by Alfred Schutz (1967) in his discussion of ‘the time structure of the project’, images conducted in the ‘Future Perfect’ tense (modo futuri exacti).

B). The solid arrows, therefore, indicate relations which can be called, following Husserl’s terminology, ‘reproductions’ – i.e. they are recapitulations of images, as completed wholes, at different time-coordinates. Copies are like ‘memories’ in the sense of inward action-replays of past experiences; ‘projects’ are, likewise, ‘replays’ of images which are still to be achieved in their final form at some future date, conducted in the present. They are, to use the terms adopted by Alfred Schutz (1967) in his discussion of ‘the time structure of the project’, images conducted in the ‘Future Perfect’ tense (modo futuri exacti).

But there is a second kind of relationship which is equally important in the construction of a temporal model of the oeuvre of Marcel Duchamp. We can call these, following Husserl, ‘retentions’ – i.e. elements which are temporally removed in the series but which are continuous with the present by virtue of their modification over time. The most important of these are indicated by backward-pointing dashed arrows (A B). A is a ‘retention’ of B when A reappears at B in modified, transformed guise. We also have a small number of image-to-image relationships which we can indicate by means of forward-pointing dashed arrows (A

B). A is a ‘retention’ of B when A reappears at B in modified, transformed guise. We also have a small number of image-to-image relationships which we can indicate by means of forward-pointing dashed arrows (A B). These are what we can call ‘open’ or ‘weak’ projects, protentions towards future images which delimit them only as a field of open possibilities rather than as a specific plan posited modo futuri exacti. The relationship between the earliest sketch-plan for the Large Glass and the final work is such an ‘empty project’, since it only provides a general framework and does not indicate the actual content of the completed image. But on the whole I have found few examples of such relationships in Duchamp’s works. Perhaps the ‘open’ project is more important in Life than it is in Art, where, in the nature of things, it is much more possible to entertain, and fulfil, positive expectations as to the evolution of future events than it is in practical affairs.

B). These are what we can call ‘open’ or ‘weak’ projects, protentions towards future images which delimit them only as a field of open possibilities rather than as a specific plan posited modo futuri exacti. The relationship between the earliest sketch-plan for the Large Glass and the final work is such an ‘empty project’, since it only provides a general framework and does not indicate the actual content of the completed image. But on the whole I have found few examples of such relationships in Duchamp’s works. Perhaps the ‘open’ project is more important in Life than it is in Art, where, in the nature of things, it is much more possible to entertain, and fulfil, positive expectations as to the evolution of future events than it is in practical affairs.

Let me briefly give an example of a chain of ‘retentional’ transformations in Duchamp’s work. There is wide agreement, among interested scholars, that the Coffee Mill Duchamp painted on a piece of cardboard to decorate his brother’s flat in 1911 contains the germ of many of his subsequent ideas. Not only is the Coffee Mill ancestral to the much better known Chocolate Grinder subsequently incorporated into the Large Glass, but we can see in the passage-rite which the coffee beans undergo as they pass through the mill an anticipation of the initiatory scenario of the Large Glass itself, and the travails of the amorous essence drawn off from the bachelors in their cemetery as it passes upwards towards the Bridal Domain.

The coffee-mill is itself a retention of a sketch of a knife-grinder dating from 1904. But more illuminating, for our purposes, is the relation which exists between the Coffee Mill with its spindly wheel mounted on a triangular base, and an epoch-making but at first sight unrelated work, the Bicycle Wheel of 1913, the first of Duchamp’s ‘readymades’. This work, at first acquaintance, strikes us mainly on account of its extreme arbitrariness, and that indeed is part of the shock-value Duchamp presumably intended it should have; but seen as a ‘retention’ it is of course not arbitrary at all, but a ‘perspectival’ modification of its predecessor, the coffee-mill, and it is itself retained as the Water Mill and Chocolate Grinder in the Large Glass. Later still, we find it retained, relatively explicitly, in the Precision Optics of 1920 (Schwarz 268) and, more extensively modified, the Rotoreliefs and Fluttering Hearts of 1935–36 (Schwarz 294, 298).

How should we consider the series, Knife Grinder  Coffee Mill

Coffee Mill  Chocolate Grinder

Chocolate Grinder  Bicycle Wheel

Bicycle Wheel  Precision Optics

Precision Optics  Rotoreliefs, as a series of retentions, retentions of retentions, etc.? Normally we speak of such sequences of related works in an artist’s oeuvre as ‘developments’ of an original idea. But this is inaccurate in so far as it suggests that the later ‘development’ is nascently present in the original exemplar, as the adult form is present in the infantile stages of a growing organism. But it cannot be said that the Bicycle Wheel is gestating in the Coffee Mill. The Coffee Mill is in no sense a sketch, or preparatory study, for the Bicycle Wheel. It is rather the case that, ‘given’ (as Duchamp is so fond of saying) the Coffee Mill, the Bicycle Wheel becomes possible as a future work of art which Duchamp, in this instance, ‘finds’ in the form of ready-made compartments – a kitchen stool and parts of a bicycle. The Bicycle Wheel is a prolongation of the Coffee Mill – the Coffee Mill ‘in the fourth dimension’. It is like the A tone on the oboe, a temporal object which endures by undergoing a continuous series of modifications; but, just as we cannot say that the latter two seconds’-worth of a four-second-long A tone are ‘present’ in the first two seconds’-worth, we cannot ‘have’ the last two seconds’-worth, as prolongations of an indivisible temporal object, without ‘having’ the first two seconds’-worth in ‘modified’ form.

Rotoreliefs, as a series of retentions, retentions of retentions, etc.? Normally we speak of such sequences of related works in an artist’s oeuvre as ‘developments’ of an original idea. But this is inaccurate in so far as it suggests that the later ‘development’ is nascently present in the original exemplar, as the adult form is present in the infantile stages of a growing organism. But it cannot be said that the Bicycle Wheel is gestating in the Coffee Mill. The Coffee Mill is in no sense a sketch, or preparatory study, for the Bicycle Wheel. It is rather the case that, ‘given’ (as Duchamp is so fond of saying) the Coffee Mill, the Bicycle Wheel becomes possible as a future work of art which Duchamp, in this instance, ‘finds’ in the form of ready-made compartments – a kitchen stool and parts of a bicycle. The Bicycle Wheel is a prolongation of the Coffee Mill – the Coffee Mill ‘in the fourth dimension’. It is like the A tone on the oboe, a temporal object which endures by undergoing a continuous series of modifications; but, just as we cannot say that the latter two seconds’-worth of a four-second-long A tone are ‘present’ in the first two seconds’-worth, we cannot ‘have’ the last two seconds’-worth, as prolongations of an indivisible temporal object, without ‘having’ the first two seconds’-worth in ‘modified’ form.

The most important relationships indicated in our synoptic figure (Figure 4.4) are, therefore, ‘retentions’ of the past, through a distorting thickness of time which modifies its contents, and ‘strong’ protentions towards the future, in the form of projects conducted modo futuri exacti. If we now take a look at this diagram as a whole, we can see that it takes the form of a dense mesh of protentions and retentions. If we take any particular work as our point of departure, it becomes equivalent to a ‘present moment’ which is a retention, in a modified form, of a fan of ‘pasts’, and which may also embody a projected ‘future’, but all these ‘pasts’ and ‘futures’ may themselves be taken up and considered as ‘relative presents’, and in each case all their (relative) ‘pasts’ and ‘futures’ take on a different shading. Thus, the Bicycle Wheel as the relative present from which the Coffee Mill is retained, is different from the Bicycle Wheel which is retained in the relative present of the Precision Optics, while at the Precision Optics, the Coffee Mill is a retention of a retention, i.e. a modified retention of the modified form in which the Coffee Mill is retained at the Bicycle Wheel – and so on. In other words, Duchamp’s entire oeuvre is a ‘network of stops’, structurally identical though on a much grander scale, to the superimposed images revealed in the Network of Stoppages with which we began this discussion.

Studying Duchamp’s total output in this way, we are amazed by the extraordinary degree of inventiveness combined with internal symbolic coherence that it displays. Duchamp played a leading role in the invention of Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, Mobile Sculpture, Minimal Art, Op-art, Pop-art, Conceptual Art and Hyper-realism, i.e. almost all the major art styles which have been introduced since the First World War, excluding Expressionism and Abstract Expressionism. Notwithstanding this diversity of forms, the extent to which the exercise of mapping Duchamp’s output as a network of protentions and retentions produces a graph which shows a high degree of connectivity throughout is extremely striking. Duchamp’s insistent search for symbolic coherence, his rigorous refusal to produce works which were not in some way elaborations of previous works and/or steps towards the evolution of further, symbolically related works, reveal the presence of a consistent artistic method, which he acquired early and never abandoned. In terms of Isaiah Berlin’s dichotomy, Duchamp was the ultimate hedgehog, who brilliantly masqueraded as a fox.

I hesitate to bring all this to a conclusion, in that doing so I am tempted to state, in still more abstract terms, the gist of what I have already said in terms already probably too abstract by half. But I can attempt to summarise my main point as follows: it seems to me that many authors who write about Duchamp, and most of whom are in agreement that Duchamp’s work throughout is to be understood as a quest for the ‘fourth dimension’, have concentrated excessively on the analysis of the occult significance of individual works, the Large Glass in particular, and have failed to reflect sufficiently on the fact that it is only in conjunction with other works produced earlier, simultaneously, or later, that this or any other work in the Duchampian oeuvre reveals its meaning. In the final analysis, the significance of any Duchamp work is never anything but relative, because it is never in the individual works, the ‘stops’, that meaning resides, but only in the gaps which lie between them. And it is by means of this thorough-going relativisation of the individual work of art, and its subjection to the field properties of the oeuvre as a whole, that Duchamp, either intentionally or somnambulistically, finally accomplished the transition to the fourth dimension, and produced his definitive answer to the Bergsonian problem.

Husserl’s model of protentions and retentions provides us with a basis for constructing a more formal model of such a relational field, but precisely because of its abstraction, its appeal as it stands is too easily confined to the minority for whom formalisation itself exerts an overriding attraction. But if we place Husserl and Duchamp in conjunction with one another, there might be enough there to suggest, even to an audience of sceptical anthropologists, something of the enticing possibilities of structural models of the temporal domain. Duchamp has provided us with an art of the fourth dimension: careful study of Duchamp might in time lead us towards an anthropology of the fourth dimension as well.

Note

1. The diagram to which Gell refers has not been discovered, and may be no longer extant. The piece reproduced here, from Art and Agency (Gell 1998: 235), does not include the dates or numbered thematic categories that Gell described. However, it seems in most other respects to be a version of the Duchamp diagram. The editors hope that it allows the reader to appreciate the ‘general gestalt properties of the figure’ constructed from Schwarz.

References

Bergson, H. 1911. Creative Evolution, trans. A. Mitchell. New York: H. Holt and Company.

———. 1958. Les Deux Sources de la Morale et de la Religion, 88e édition. Paris: PUF.

Dorsey, J.O. 1894. ‘A Study of Siouan Cults’, 11th Annual Report (1889–1890), Bureau of Ethnology. Washington, pp. 361–544.

Findlay, J. 1975. ‘Husserl’s Analysis of the Inner Time-Consciousness’, Monist 59(1): 3–20.

Gell, A. 1992. The Anthropology of Time: Cultural Constructions of Temporal Maps and Images. Oxford: Berg.

———. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon.

Gray, C. 1953. Cubist Aesthetic Theories. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press.

Henderson, L. 1983 The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Husserl, E. (1928) 1964. The Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness, ed. M. Heidegger, trans. J.S. Churchill. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

James, W. 1890. Principles of Psychology. London: Macmillan.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962) 1964. Totemism, trans. R. Needham. London: Merlin Press.

Schutz, A. 1967. The Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Schwarz, A. (ed.). 1969. The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. New York: H.N. Abrams.

Wind, E. 1958. Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance. London: Faber and Faber.

B

B

B) indicates that B is a copy of A, i.e. B is a later work which substantially reproduces the actual visual appearance of A, when there is no reason to think that A was produced in order to serve as a ‘project’ (a preliminary sketch) for B.

B) indicates that B is a copy of A, i.e. B is a later work which substantially reproduces the actual visual appearance of A, when there is no reason to think that A was produced in order to serve as a ‘project’ (a preliminary sketch) for B. B). A is a ‘retention’ of B when A reappears at B in modified, transformed guise. We also have a small number of image-to-image relationships which we can indicate by means of forward-pointing dashed arrows (A

B). A is a ‘retention’ of B when A reappears at B in modified, transformed guise. We also have a small number of image-to-image relationships which we can indicate by means of forward-pointing dashed arrows (A B). These are what we can call ‘open’ or ‘weak’ projects, protentions towards future images which delimit them only as a field of open possibilities rather than as a specific plan posited modo futuri exacti. The relationship between the earliest sketch-plan for the Large Glass and the final work is such an ‘empty project’, since it only provides a general framework and does not indicate the actual content of the completed image. But on the whole I have found few examples of such relationships in Duchamp’s works. Perhaps the ‘open’ project is more important in Life than it is in Art, where, in the nature of things, it is much more possible to entertain, and fulfil, positive expectations as to the evolution of future events than it is in practical affairs.

B). These are what we can call ‘open’ or ‘weak’ projects, protentions towards future images which delimit them only as a field of open possibilities rather than as a specific plan posited modo futuri exacti. The relationship between the earliest sketch-plan for the Large Glass and the final work is such an ‘empty project’, since it only provides a general framework and does not indicate the actual content of the completed image. But on the whole I have found few examples of such relationships in Duchamp’s works. Perhaps the ‘open’ project is more important in Life than it is in Art, where, in the nature of things, it is much more possible to entertain, and fulfil, positive expectations as to the evolution of future events than it is in practical affairs.