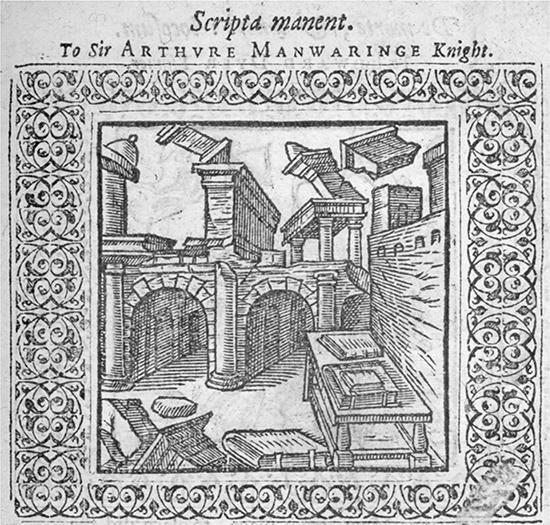

7.1 G. Whitney, A Choice of Emblemes (Leiden: C. Plantin, 1586), sig. R2r (‘Scripta manent’) © British Library Board (pressmark 89. e. 11).

Gell and the Magic of the Early Modern Book

Let me start with a confession. Before Liana Chua spoke on the first morning of the ‘Art and Agency: Ten Years On’ symposium, I did not know how to pronounce Alfred Gell’s surname.1 I had never talked in person to anyone who knew him or his work, either before or after his death, besides one or two friends to whom I had recommended the name. Yet I had had a relationship with him for about ten years. One day in 1998 I entered Heffers bookstore in Cambridge to scan, as usual, the various sections for interesting new publications. I pulled Art and Agency down from the shelf in ‘Anthropology’. I definitely wanted, I thought, more agency in my art. I remember being attracted both by the cover design and by the photo of the author on the back. I started listening to his voice as I read it off the page, talking back in my own voice in my head. The conversation has been incessant since. My point is that there could hardly be a better example of an index of a social relationship than a book, and no more enchanting technology than the technology of letters, handwriting and the codex. Letters are ripe for consideration as a technology that magically extends the operations of human faculties, books as residues of performance and agency in object form.

Yet neither Gell nor his followers have applied his ideas to the technology of letters and books. With few exceptions, his model of the ‘art nexus’ has been applied to visual art and material culture. This is hardly surprising. As an anthropologist, Gell dealt principally with non-literate societies (or societies that have only acquired literate skills in the context of recent contact with European explorers).2 In Art and Agency, he says unequivocally: ‘I do not wish to discuss literary theory, since I am only interested in visual art’ (1998: 34). At the end of his essay ‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’ he acknowledges that language ‘is the most fundamental of all technologies’ (1999: 183). He leaves the door open for Gellian studies of verbal, poetic art as a kind of musical or performance art. One or two such studies have duly followed (Weiner 2001). But in setting his whole stall out against the reading of visual art as encoded texts, Gell betrays little or no inclination to consider texts as indexes of art-like agency relations. Where he uses European art he sticks to concept art and Renaissance paintings and sculptures; otherwise it is a matter of objects such as carvings, nail fetishes and hunting nets, objects that – unlike books – do not have inscribed meanings. He does not mention that Michelangelo’s Moses is holding the tablets upon which God is to write his laws (1998: 59). He leaves ‘letters’ out of the picture.

The best example of a Gellian ‘index’ is a malanggan carving, a statuette that temporarily objectifies memories for particular recipients during a ceremony, and is disposable once those memories are internalized (Küchler 1987, 1988, 1992; Gell 1998: 223–28). Its purpose is the transmission of ancestral social efficacy or empowering knowledge (wune). When an inhabitant of northern New Ireland dies, indexes of their agency still abound everywhere (i.e. their gardens and plantations, wealth and houses, wives and husbands), but they are not concentrated anywhere in particular. So all the dispersed ‘social effectiveness’ of the deceased is collected into a single memorial carving of an ancestral figure accompanied by a variety of subsidiary motifs. A whole political economy works by means of these carvings. Gifts of money entitle the donors to ‘remember’ (in an active sense) the image on display, and it is this internalized memory, parcelled out to the contributors to the ceremony, which in turn entitles them to social privileges. Social relationships are then legitimized on the basis of previously purchased rights to remember the ancestral carvings and their motifs.

The anthropological premise here is that an image of something can be a distributed part of that thing, can share its actual efficacy as though it were a limb. The malanggan, moreover, is the entire distributed person. Each carving acts as a material index from which the deceased’s accumulated effectiveness is abducted by attendants at a ceremony, attendants who then redeploy that effectiveness (in the form, for example, of concrete social privileges) in their own social lives. The carving transmits – within a network of past and future relationships – the social agency (‘the entire agentive capacity’) of the deceased to privileged recipients for future redeployment. The malanggan ceremony is, as Gell puts it, ‘the supreme example of abduction of agency from the index, in that the other’s agency is not just suffered via the index; it is also thereby perpetuated and reproduced’ (Gell 1998: 227; italics in original).

This is just one, central example. Gell explores the multifarious ways in which artistic indexes extend their maker’s or user’s or prototype’s agency, and mediate relations between all these participants in an art nexus.3 They do this through technologies of enchantment (Gell 1999: 159–86), defined as processes that radically transform materials into works of art in ways that resist the attempts of recipients mentally to encompass them. The malanggan is charged with efficacy by a specialist technique of heating and burning, and its ornamental motifs brought out with paint. Ornament is ‘unfinished business’. The ornamental complexity of the art object exceeds the viewer’s ability to organize the visual field, entrapping him or her in a kind of cognitive limbo, in a never-ending exchange or ‘biographical relation’ with the index. Gell describes this capacity of visual patterns as ‘cognitive stickiness’ and argues that it has social functions (1998: 80–81, 86; Rampley 2005: 531–36).

Any attempt to apply this model to the study of literate culture is in danger of seeming perverse. Gell’s virtue was surely to have moved us ‘beyond text’ to performances, sounds, images, objects – a movement given further momentum in recent years by £5.5 million of the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s money. But I will argue that far from being perverse, it is salutary. By the late 1990s, when Gell’s last books came out, the field of literary-historical study was itself more than ready to move beyond text, beyond the routine analysis of texts-in-contexts, of the production – via textual and text-like ‘representations’ – of ‘meanings’ that symbolically ‘constructed’ cultural identities and systems.

In this field, at that moment, Gell’s theory of art and agency offered itself as a powerful tool of counter-enchantment to at least one researcher still in the debilitating grip of the ‘writing culture’ phenomenon that had gained ground since the early 1980s. Like so many scholars of Renaissance England, I had been captivated by Stephen Greenblatt’s new historicism, which combined anthropology, history and text studies in novel and exciting ways (Greenblatt 1980). Greenblatt caused scholars in art and literary history to renew their attention to art and literature as major means of social- and self-definition. But his choice of theoretical models (Clifford Geertz, Michel Foucault) tended to reify art and literature as ‘texts’, ‘representations’ and ‘discourses’ spun together in ‘webs of meaning’ that entangled the subject. There was a danger of being left only with the self-reproducing conditions of language, ideology, discourse (Drakakis 2001; Salkeld 2001; Brett 2002). How were we to get back to the notion of art as an intentional activity embedded in social process, while eschewing the increasingly sterile attempt to communicate with the early modern dead, to connect – as this usually meant in practice – with literary authors’ subjectivities, especially Shakespeare’s subjectivity?

When I stumbled across Art and Agency in the Cambridge Heffers in 1998, the concept of the art object as an ‘index’, as a ‘congealed residue of performance and agency in object-form, through which access to other persons can be attained, and via which agency can be communicated’ (Gell 1998: 68), seemed revelatory in this respect. It promised to displace the theories of semiotics that had dominated cultural studies for so long, theories which had been concerned overwhelmingly with mimetic modes of representation and with symbolic conventions.4 In the event, of course, it has not displaced them. It has – in the work of art historians such as Shirley Campbell (2001) and Jeremy Tanner (2007) – provided a strong shot in the arm for the existing study of the cultural and social contexts of art.

Gell’s attempt to put the study of art and agency at the centre of anthropological inquiry was compatible with a trend in historical inquiry that pre-dated the publication of his last works. A group of applied historicist approaches had developed alongside new historicism, especially in Britain and on the North American East Coast. The scholars involved were far from having a common programme. But they were all in the business of reintegrating the study of culture and society by inferring agency relations from artefacts resituated in their dynamic contexts of original use and transmission.5

Concepts and questions from social anthropology, archaeology and other applied social and linguistic sciences often feature in this broad strand of historical work.6 It analyses events from the point of view of historical actors, asking what they were doing, recovering ranges of possible choices and outcomes in different historical situations and controversies. It counters rigid, one-way or top-to-bottom models of cultural transmission by reconstructing circuits and networks of agents and patients. Above all, practitioners work at applied points of connection between art and society, both in the past and in the present. Artefacts are re-read as deposits of social relations and exchanges. The historical actors are as likely to be the recipients or transmitters of artefacts as they are to be their artistic or creative point of origin. The ‘background’ historical process of the transmission or transfer of culture is held to be a primary object of study, to deserve as much attention and contextualization as the canonical texts and events of history proper.7

Once placed in this broader intellectual context, and complemented by the historian’s concern with cultural conventions and social institutions, Gell’s model for the analysis of artworks has a claim to being the most important to emerge in any discipline in the last decade.8 Instead of trying directly to communicate with the dead and their inner ‘selves’, we can use it to try to hear and see them communicating with each other by means of specific techniques and artefacts. Historians of ideas can take more consistently into account the fact that their sources are not just ‘texts’ to be appreciated and interpreted but objects with functions and social lives.

But, you might immediately object, neither a literary ‘work’ nor a particular ‘text’ of that work is an artefact in the strict sense, and Gell’s theory is designed for artefact-oriented fields of study.9 In medieval and early modern literary studies, I reply, the departure point is not always the work or the text; it is often the recovery of a specific literary nexus as described by a historical agent or revealed by the particularities of a manuscript or printed book. An example follows in the second half of this chapter. If the study of early modern ‘visual culture’ and ‘material culture’ takes objects sorted into distinct categories by posterity and by museums, and regroups them as the material traces of social processes from domestic living to dying, the study of early modern literary culture now does something similar. Printed and manuscript objects are restored to the circuits of authors, editors, printers and reader-writers who produced and used them. In the process, literary documents become artefacts that witness to histories and agencies in ways that art historians and even archaeologists might recognize (Johns 1998; Frasca-Spada and Jardine 2000; Olson 2004).

Historians of the early printed book now insist not only that each edition of a book was a distinct event produced in particular cultural and political circumstances, but that each so-called ‘copy’ of a book was in fact unique, whether by virtue of the manual printing process itself, or by virtue of users’ interventions (McKitterick 2003: 123, 134, 139; Myers, Harris and Mandelbrote 2005; Pearson 2007). The arrival of the digital age and of virtual texts has combined with other factors to blunt what had become too sharp a distinction between a late medieval manuscript culture of unique artefacts and an early modern print culture of ‘mass’-produced copies (Crick and Walsham 2004). At the same time, the Internet has begun to turn images from particular editions and unique copies into objects of common reference.10 All editions, not just first editions, have become events in their own right. Copies of printed books in which readers inscribe their personal judgements, or which are in other ways the occasion for memorial writing, attract the kind of attention previously lavished only on medieval manuscripts.

More broadly, during the 1990s, historians and anthropologists shook off the Whiggish association of literacy with progress towards modern critical rationality (Halverson 1992). They now trace the history of literacy as a type of technology that extends the agencies of minds and voices in particular material forms, and the history of literary artefacts as objects whose making, keeping and use brings people and objects into distinctive types of social relations with one another (Clanchy 1993; Martin 1994; Chartier and Messerli 2000).11 They study the literate arts of memory, and the material forms and social networks by means of which transcribed knowledge was transacted and transferred. They recover the material specificities of the literary technologies – such as the commonplace book – whose use shaped the organization and retrieval of knowledge in the early modern period. Rather than viewing the book as a discrete entity that holds the key to its interpretation inside itself, these scholars approach the book as ‘the focal point of a wide network of social interactions, material objects, and intellectual techniques’ (Wolfe 2004: 145).

Gell’s work should be seen as timely, in other words, not just for art history but for all the fields in cultural and intellectual history that have been converging in the last twenty years on more applied approaches to the sources, to the surviving tools and objects from the medieval and early modern period. Although he is interested more in the temporality of relations between persons and things than in history in the round, Gell provides a set of questions that can restore artefacts in all media to the historical dynamics of relations between agents and patients (as described by participant-observers). What exactly is the index? Whose agency is being indexed? In relation to whom? In the performance of which mental operations and/or social actions? In whose description or representation is all this judged to be so, and for what ulterior reasons? Intellectual and cultural history is recast as the history of art nexuses, of shifting agency relations between artists, recipients and prototypes as mediated or indexed by specific technologies and artefacts.12

In literary-historical study, this kind of approach can help us to abandon all sorts of ingrained assumptions about the agency relations and actions normally indexed by literary artefacts, and to test grand theories about orality and literacy, manuscript ‘culture’ and print ‘culture’ against particular nexuses. So in different circumstances a literary index might point primarily to the agency – whether as a matter of authority or skill – of the person ‘behind’ it or represented in it, the artist who wrote it, the people or company who perform or speak it, the patron or privileged diffuser to whom it is addressed, the bookseller who distributed it, the readership who make it a commercial success and who then use it to index their own actions and relations.

Gell’s model specifically encourages us to ask what actions are carried through by means of art objects, and what kinds of relations are found in their vicinity. These questions can be applied to the products of literary technologies. What things can be done, what transactions carried out, what relations formed by means of the products of reading and writing in any given historical nexus? In the early modern period, historians now tell us, writing was primarily understood to be an instrument of social transactions, while reading was intended to give rise to something else (Jardine and Grafton 1990: 30; Richardson 1999: 102). The crafting and consuming of literary artefacts indexed other kinds of action and behaviour, from the conversational to the political. Specific shared conventions shaped this behaviour; specific critical or moral languages were deployed to derive such behaviour from literary artefacts.

The letter (in the sense of an epistolary communication), for example, was the staple tool for effecting transactions across space and time throughout the medieval and early modern periods. Indeed, the nexus of a medieval or early modern letter might situate it as: a beautiful artefact on display; a disposable medium for a pragmatic communication; a collectible trace of a public, ceremonial letter-exchange with written, visual and oral aspects; an invented model to teach practical letter-writing or communicate knowledge; a ‘memoir’ preserved in a register or collection for future reference. It could be written in holograph or dictated to a servant; it could be written by a servant on behalf of a master who just signed it. When received it could be read privately and silently by one individual, read aloud by one person to another person or persons in more or less public spaces, or copied in manuscript for private reading by others (Mullett 1990: 172–85; Garrison 1999). And if we want to identify a type of letter-nexus that more specifically indexes Gell’s ‘art-like’ relations, then we need look no further than the letter of friendship, which for early modern intellectuals like Erasmus makes an absent person present (Jardine 1993).

But there are, of course, problems. Gell’s four terms for entities which in passive or active modes can be in art-like relation (indexes, artists, recipients, prototypes) clearly emerge from the analysis of visual and material culture, and are not so readily applicable to the types of agents and patients bound in relations by literary artefacts. And the latter clearly do function in different ways to other artworks; they cannot be assimilated to ‘material culture’. They directly index discursive behaviour – speech and thought – in ways that paintings and statues generally do not. There are complex questions about the relationships between terms such as ‘text’, ‘edition’, ‘book’ and ‘work’ that do not arise in material culture studies and that would have to be addressed before Gell’s model could be considered fully applicable to the study of literature.

Furthermore, Gell has nothing to say about the formation, use and circulation of the discourses of judgement that provide him with his raw material – namely, the narratives and anecdotes of participant-observers in art nexuses.13 In other words, concepts from literary theory equivalent to ‘paratext’ and ‘critical discourse’ are missing from Gell’s anthropology of art. As he is focused on visual and material culture, and wants to keep problems of ‘discourse’ – for the most part – in a separate, unopened box, he considers neither the case of a work of art that carries with it discursive examples of the way it might be judged or discussed, nor the notion that discursive judgements of art objects are themselves artefacts shaped for particular purposes.

There is at least one important exception to this: his references to the ways in which sung poems not only index competitive social interaction or the operations of magic, but discursively situate other objects as indexes of agency. In a 1995 paper, Gell tells us that in Dinka society ‘[i]t is the song, or rather, the public nexus created by the song, between the owner and his animal, which creates the ox as artwork, just as it is the interpretation, poised between artwork and recipient, which brings into existence the artworks of the [W]estern art world’ (1999: 227).

This train of thought was not to be developed in Art and Agency, composed a year later. But it is important to the historian of early modern culture, for whom nexuses are largely created in writing, not song. Material objects carry inscriptions and generate paratexts with their own contexts and purposes in the documentary record. Literary artefacts include and infold paratext and commentary in highly sophisticated ways. To select and judge the manuscript and printed works they might collect and take extracts from, early modern reader-writers wanted to know, and producers were obliged to reveal (on title pages, in the case of printed books), a wider range of things than modern readers would typically consider: by whose command or permission the work had been circulated and upon what occasion, by which person of what religious character and moral and intellectual capacities it had been composed, to whom it had been given or dedicated and why, to which authorities and methods it was indebted, and where and by whom it was published, recommended and sold.14

Beyond the obligations and debts of this kind with which a work (especially a printed work) might visibly present itself, there were those it was rumoured to have but did not advertise in print or writing (especially in the case of a manuscript work), and those particular to individual copies as passed on between donors and recipients. Much of this information was transmitted orally, and survives in written form only in very rare cases. There was also the crucial matter of how the reading of particular books was being directed, and by which authorities, in the context of which contemporary intellectual topics and controversies. On all this depended the ‘credit’, the perceived credibility and value of the book in question. The transmission of such ‘supplementary’ knowledge was subject to deliberately manipulated publicity, even falsification.

That is to say, competing moral and social stories about the making and transmission of any new or relatively unknown work – whose mind or agency was ultimately behind it and whether they were of good morals and doctrine, who actually invented or compiled the book, upon what occasion and in the context of which relations – were vital in shaping their credit and use in the conversational culture of the time, and were therefore liable to artful fashioning.

Let us, then, briefly consider an example of an early modern book and an artfully fashioned story about its making and transmission. The example is intended to resonate with the function of malanggan carvings, to help us to see the publication and circulation of a book in related, though not identical terms. For a book (to repeat the terms of Gell’s analysis of the malanggan statues) could also aim to transmit – within a network of past and future relationships – the social agency (‘the entire agentive capacity’) of a person to privileged recipients for future redeployment. In the sixteenth century, books and writings were, with portraits, one of the principal artificial means by which elite families archived and transmitted – for perpetuation – both their natural or racial ‘goods’, consisting on the one hand of physical traits and inherited morals, predispositions to virtue and knowledge, and their external or material goods, such as their wealth, honours, alliances and privileges. It is in this context – the public transmission of familial charisma or ethos – that we shall place the history of a book which describes itself as a self-portrait addressed from a father to a son.

It is an example which we can usefully attach to a philosophical statement by an important early modern thinker (Francis Bacon) about the nature of literary artefacts. In Bacon’s statement, litterae or ‘letters’ refer us not – as the term ‘literature’ now does – to the literary creations of authors, but to a technology that mediates human commerce in general (Fumaroli 2002: 25). ‘Letters’ act for people – especially great people – in networks of agency extended across time and space, in ways that could be construed as magical in the sixteenth century. Baudouin reported in 1561 that when the inhabitants of the West Indies heard that Christians ‘could converse with one another through letters, while at a distance . . . they worshipped the sealed letters, in which they said some sort of divine spirit (“divinum internuncium genium”) must be enclosed, that reported the message’ (Grafton 2007: 113). Furthermore, the durability and range of letters is greatly extended by the newly invented art of printing. More specifically, Bacon offers us an account of the ways in which literary technology was understood to extend the agency of the noble patron or scholar-gentleman in his absence (Wintroub 1997: 208).

This account elaborates upon a number of commonplaces: that words fly while ‘writings remain’ (scripta manent), that the images of men’s minds remain in books, that books carry commodities like ships, that letters indicate absent voices and bring things to mind through the windows of the mind, and that the Word is the resurrection of the Spirit. Here I shall emphasize two of these. The first is the classical notion of the library as a space where you meet imagines ingeniorum, images of the innate qualities or genius of great men. It was found in sources such as Pliny’s Natural History (35:3), and revived by Renaissance humanists. The images were to be met simultaneously in portraits and statues ornamenting the room, in the beginnings of the books (as preliminary figures), and in the texts themselves. The second is a still more widely diffused commonplace of medieval origin: verba volunt, scripta manent, ‘spoken words fly off, writings remain’. In Geoffrey Whitney’s emblem (Figure 7.1) on this theme (Whitney 1586: sig. R2r), scripta remain alive in posterity to discourse of great men’s acts when all other media, not just the spoken word, perish: ‘[i]t is through their living quality that books bear in them a particular – metaphysical – way of staying alive, which sets them apart essentially from the deadness of solid building materials such as stone, brass, or steel’ (van der Weel 2004: 325). Writings remain, that is, as animate persons in object form. They are Gellian indexes par excellence.

So how does Bacon develop these two themes? Bacon concludes his arguments for the dignity of knowledge and learning with their contribution to human nature’s highest aspiration. Fundamental human processes such as ‘generation [procreation], and raysing of houses and families . . . buildings, foundations, and monuments’ all tend towards ‘immortalitie or continuance’. But the monuments of wit and learning are more durable than artefacts made by power and the manual labourer. The verses of Homer have survived in a more perfectly preserved state than ancient buildings and temples. It is not possible, he continues,

to haue the true pictures or statuaes of Cyrus, Alexander, Cæsar, no nor of the Kings, or great personages of much later yeares; for the originals cannot last; and the copies cannot but leese [lose] of the life and truth. But the Images of mens wits and knowledges [Ingeniorum Imagines] remaine in Bookes . . . capable of perpetuall renouation: Neither are they fitly to be called Images, because they generate still, and cast their seedes in the mindes of others, provoking and causing infinit actions and opinions, in succeeding ages. So that if the inuention of the Shippe is thought so noble, which carryeth riches, and commodities from place to place, and consociateth the most remote regions in participation of their fruits: how much more are letters to be magnified, which as Shippes, passe through the vast Seas of time, and make ages so distant, to participate of the wisedome, illuminations and inuentions the one of the other? Nay further wee see, some of the Philosophers . . . came to this point, that whatsoeuer motions the spirite of man could act, and perfourme without the Organs of the bodie, they thought might remaine after death; . . . But we . . . know by diuine reuelation . . . not only the vnderstanding, but the affections purified, not onely the spirite, but the bodie changed shall be aduanced to immortalitie, doe disclaime in these rudiments of the sences. (Bacon 2000: 52–53)15

7.1 G. Whitney, A Choice of Emblemes (Leiden: C. Plantin, 1586), sig. R2r (‘Scripta manent’) © British Library Board (pressmark 89. e. 11).

Here is an early modern theory of writings as indexes of agency, as, indeed, the most potent indexes available to the artist, the prototype, and the recipient. It passes over the manifold problems involved in achieving correct copies of texts using the printing press in the early seventeenth century. As a conveyance of written letters, a copy of a text is declared to have an efficacy beyond that of copies of paintings and statues, which quickly lose the life and truth of the originals.16 Using metaphors from theology, natural philosophy and international commerce, Bacon describes the quasi-magical capacity of letters – especially in the form of the durable, reproducible, transportable products of the printing press – to carry human agency into effect at distant points in time and space, to facilitate transactions between agents in remote regions. The theory is informed by historically specific concepts of agency, and of the participants in an art nexus, but it is still, I would contend, compatible with Gell’s model.

Bacon’s point in the second half of the passage is that letters do more than archive voices for future hearing or things for future seeing; they facilitate all kinds of physical and spiritual commerce between human beings. Erasmus had wondered in his Paraclesis (1516) whether the Christ portrayed in the living gospels did not live ‘more effectively’ than when he dwelt among men. Christ’s contemporaries saw and heard, Erasmus claimed, less than readers may see and hear in the text. The written gospels ‘bring you the living image of His holy mind and the speaking, healing, dying, rising Christ himself, and thus they render Him so fully present that you would see less if you gazed upon Him with your very eyes’ (O’Connell 2000: 36, 155). An Anglican preacher would write in the later seventeenth century that to read and digest the Bible is to have your conversation in heaven and to be ‘transformed into the image of it, be acted by the spirit which breaths in it’ (Rainbow 1677: 61–62). Bacon transfers the theological concept to humane letters and to secular conversation.

On the one hand, like a deceased human body at the resurrection, a literary artefact such as a manuscript letter or a printed book is capable of ‘renovation’; its spirit, its action and purpose can be fully renewed in the ‘afterlife’. Whatever ‘motions the spirite of man’ – not to mention the purified motions (in Christian theology) of his appetite and body – ‘[can] acte, and perfourme’ after death, can be acted and performed by means of the renovated letter. On the other hand, letter-images comprise seeds that take the form of a posterity of action and opinion when planted in the minds of others and regenerated by their agency. The notion of minds as gardens in which grew seeds of virtue and knowledge was also a commonplace one (Horowitz 1998). The seeds or semmae to which Bacon refers are themselves agents in the process of generation of bodies; in natural philosophy, they explain how divine ‘wit and knowledge’ generates living forms (Shackleford 1998).17

Either way, the sensible images carried in literary form by books are attributed with an essentially performative function: they carry the motions of the human body-and-spirit into effect; they are the means by which an intended action is carried through. In playing this role, they can be seen both as secondary agents and as patients; they are both extensions of the agency of their prototypes and makers, and vessels ‘capable’ of renovation in the hands of life-giving recipients. They have no afterlife unless the ‘motions’ they mediate are acted and performed. The fundamental principle is theological, even if the applications Bacon has in mind are secular: letters are the instruments by means of which the human body-and-spirit is resurrected to live and act again in the afterlife of posterity.

Posterity begins in the here and now. Bacon elsewhere gives us a practical example of a book which carries images of the wit and knowledge of a great and noble personage, which acts and performs the motions of his spirit, and – as we shall see – of his body, in ways that provoke and cause actions in others: the Basilikon Doron of King James VI of Scotland and I of England.18 For our purposes we can think of this as a literary portrait of a monarch talking to his son, giving him instructions on how to be king. Following Jeremy Tanner’s lead, we can try to push beyond conventional interpretations of the portrait as a ‘representation’ of royal ‘authority’ by considering it in a particular nexus. On one level the nexus is clearly that of a gift from father to son, and can be analysed in Maussian terms (Scott-Warren 2001). But we can also go on to ask, with Tanner, what specifically is the character of the prototype’s agency in this portrait-like situation? How exactly does the prototype causally determine the character of the index, and with what consequence for the portrait’s effect on the recipient/patient? What material technology is being used? To what extent is the recipient able to act as agent in relation to artist, index and prototype, and how is such agency realized (Tanner 2007: 71)?

James’s work started life in 1598 as a manuscript advice book addressed – it seemed – in a private family setting to his young son Henry. In 1599, an edition of seven copies was printed for a select court audience. Only in 1603 was the work published openly, in Edinburgh and London, in editions that coincided with the death of Elizabeth and James’s accession to the throne of England. Thereafter it enjoyed a very wide national and international circulation. Bacon’s two comments on the nexus of the 1603 edition (one in Advancement, one in a 1609 manuscript work) reveal what his anthropology of literarily mediated agency meant in practice. Bacon understood the 1603 London edition to be an artfully fashioned ‘live’ image of a private discursive performance: James giving wisdom to his young son. It was artfully fashioned in that it was rhetorically designed to have a specific effect upon ‘onlookers’ – the public who buy the book in anticipation of James’s physical arrival in his new kingdom of England in 1603. Bacon claims secondary agency as a privileged recipient or observer of both the book and the king. He does so in the context of a larger bid to promote – to have the new king promote – the standing of ‘letters’ and learning in England.

The ‘actions and opinions’ Bacon understood the book to be designed to cause were very precise. We might say that it possessed a historically specific form of ‘cognitive stickiness’. It was not just consumed as ‘advice’; it caused the audience to linger on the rhetorical pattern of its composition in ways that set up – in Gell’s terms – an enduring biographical relation between the book and its recipients, the king and his new subjects. The aesthetic properties of the work ‘are salient only to the extent that they mediate social agency back and forth within the social field’ (Gell 1998: 81).

So the audience in London in 1603 were able to form an opinion of the king’s whole ‘disposition’ and ‘conversation’ by making detailed inferences from the images the book offers of James’s ‘wit and knowledge’ in action. In general terms they were able to see a king conversant with all the arts and sciences across the whole sphere of ‘humane’ and divine learning. But they also abductively inferred the balance of James’s bodily humours, the motions of his spirit and of his internal faculties from the internal process revealed by the book. They could not have inferred these things – or so Bacon might have said – from a copy of a picture or a statue of the king.

In the logic and psychology of the day, mental operation involved two principal moments: ‘inventing’ – collecting perceptions and experiences received through the senses (whether from books or from nature) and shaped for mental use by the imagination; then ‘judging’ – either assessing them and deciding to act upon them, or organizing them in order to present or sway opinions (Jardine 1974: 8, 31–32):

In myne opinion one of the moste sound & healthful writings that I haue read: not distempered in the heat of inuention nor in the Couldnes of negligence: not sick of Dusinesse as those are who leese themselues in their order; nor of Convulsions as those which Crampe in matters impertinent: not sauoring of perfumes & paintings as those doe who seek to please the Reader more than Nature beareth, and chiefelye wel disposed in the spirits thereof, beeing agreeable to truth, and apt for action . . . (Bacon 2000: 143)

The king’s writings show his temperament to be naturally disposed to decorous inventing, ordering, disposing and ornamenting of pertinent matters, and to be generally agreeable to truth and apt for action. It is not just, however, that the book offers the reader the kind of intimacy with the king’s physical presence afforded to his physician or confessor – close enough to observe every sign and symptom of his temperament and disposition, to smell his perfume and judge his cosmetics. The mention of the ‘perfumes’ which prepare us for the king’s bodily presence provides an important link with Bacon’s other, 1609 comment on the king’s book, in an incomplete ‘History of Great Britain’ that was only published much later.

In this 1609 comment, Bacon makes it clear that in 1603 the ‘book falling into every man’s hand’ filled the whole realm ‘as with a good perfume or incense before the King’s coming in’. It satisfied ‘better than particular reports touching the King’s disposition’ and ‘far exceeded any formal or curious edict or declaration’ that a prince might use at the beginning of their reign to ingratiate themselves in the eyes of the people (Bacon 2000: 332). Bacon’s point is that the Basilikon Doron as a whole could be seen as one highly efficacious, artificial index of the king’s physical action in entering his new realm in a way that would ingratiate himself to his people, show him as agreeable to truth and apt for action. It was more efficacious than other dispersed indexes such as particular reports of his disposition, and edicts or declarations seen and heard across the realm, because it took us artfully into his physical presence, and allowed us abductively to infer the qualities of his soul.

Does the technology of letters, handwriting and the book still have the same magical power in contemporary culture? Would a contemporary intellectual argue before a ruler that literary media are more efficacious than visual media? Politicians such as Barack Obama (Dreams from My Father, 1995) still use books to introduce themselves personally to electorates, but could their efficacy be compared with that of televisual and Internet media? And what does the prominence of ‘old’ types of writing and books in contemporary popular narratives tell us about the place of these technologies in broader culture?

When incarnate as a student named Tom Riddle at Hogwarts in the 1940s, Lord Voldemort created a Horcrux consisting of an apparently blank diary in which he hid a fragment of his soul. Fifty years later, Harry Potter finds the empty diary, dips his quill into a new bottle and begins to write. As he writes, Tom Riddle writes back, with the words dissolving quickly away each time. In one exchange, Potter writes that someone had tried to flush the diary down the toilet; ‘[l]ucky that I recorded my memories in some more lasting way than ink’ writes back Riddle. Before long, Harry sees that ‘the little square for June the thirteenth seemed to have turned into a miniscule television screen’; he tilts forward and his body is ‘pitched headfirst through the opening in the page, into a whirl of colour and shadow’. He is soon in the living presence of the author of the diary (Rowling 1999: 179–84).

Here, and in other popular novels and films such as The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008) and Inkheart (2008), is perhaps a pop-cultural residue of the medieval and early modern understanding of the magic of letters, handwriting and the manuscript or printed codex. Such narratives appear to show us once more the power of these linked technologies as they enable people to communicate with others in distant places and times. Readers in these stories are transported into the living presence of others, even after their deaths. But do such episodes celebrate the enduring power of ‘pen and ink’ and the physical book? Or do they represent nostalgia for a broken or lost communications magic? And, if so, what exactly is broken or lost? Is it perhaps the link between these technologies that is broken, rather than the magical hold upon us of the technology of letters, which, after all, is now carried abroad by the e-book reader, the mobile phone, the computer keyboard and the Internet? Is it perhaps the centuries-old, unchallenged dominance of the power to transmit and receive written wit and knowledge across space and time that is lost, rather than that power itself? Bacon believed a sovereign needed to harness this power above all others. But now we have learned to do what could not be done by copying pictures and statues in Bacon’s day: ‘to transmit the image in all its movement and sound [across space and time] in all its instantaneousness’ (Martin 1994: 511).

Rowling appears to acknowledge that the power of writing and the book – even in the case of her own series – is now more relative than it was; or, at least, that she is writing for a generation for whom internal ‘conversation’ with the printed and written word is no longer as powerful as digital communications (which still relies on the technology of letters) and the digitalized moving image. The existence of an online, interactive version of Tom Riddle’s diary points us to the ascendant communications technologies whose magical power to index agency displaces that of handwriting and the paper book – if not that of letters per se – both within Rowling’s novel (the ink dissolves and the page becomes a television screen, a whirl of colour and shadow), and in the translation from the written to the filmed sequence in which Harry chats with Tom Riddle and then immerses himself in a virtual world: instant messaging over the Internet, video games, digital film and television.19

1. My thanks to Simeran and Rohan Gell for their encouragement, to Susanne Küchler, to the organizers of the symposium, Liana Chua and Mark Elliott, and to Jason Scott-Warren, who brought my interest in Gell to Liana’s attention, and to whose brilliant work on the early modern book-gift I am responding throughout this chapter. See Scott-Warren (2001: 1–18).

2. Exceptions include Hindu India and ‘seminar culture’ at the LSE, which he wrote about in Gell 1999.

3. It is important to reserve the term ‘nexus’ for a particular instance in which an art object is judged to index art-like agency relations between specified participants. It is not to be confused with a ‘network’ of the kind studied by social and intellectual historians, which might be thought of as the generalized set of relationships that emerges from multiple related art nexuses.

4. Gell draws selectively and creatively on C.S. Peirce’s threefold classification of the qualities of signs as iconic, symbolic, and indexical (by discarding the former two), and on his and other logicians’ classifications of an ‘abductive’ mode of inference. He does so in order to distinguish ‘art-like relations between persons and things from relations which are not art-like’ (1998: 13). See the critique of Gell’s treatment of semiotic and aesthetic approaches in Layton (2003). Some of Layton’s individual points are telling. But the change of emphasis heralded by Gell’s work was certainly needed in the late 1990s. It is not, pace Layton, that Gell sought to exclude the iconic and symbolic qualities of signs from consideration. Rather, he was saying that the indexical qualities of signs had been severely neglected due to the particular aesthetic preoccupations of modern users of art and literature, including anthropologists.

5. I am thinking of figures such as Michael Baxandall in art history, Natalie Zemon Davis in social history, Quentin Skinner in the history of political thought, Elizabeth Eisenstein and Adrian Johns in the history of the book, Mario Biagioli and Steven Shapin in the history of science, and Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine in Renaissance studies. On the legacy of Natalie Zemon Davis’s refusal to distinguish absolutely between ‘artefacts and ideas, society and culture’, see Diefendorf and Hesse (1993: 2–3).

6. On social archaeology and its developments since the 1970s, see Meskell and Preucel (2004). For an important development (the ‘relevance theory’ approach to cognitive pragmatics) in linguistics and psychology, see Sperber and Wilson (1995).

7. On this last point, see especially Grafton and Blair (1990). For some of the results of the University of Oslo’s project on ‘Dislocations: Practices of Cultural Transfer’ (2003–2009), see Cave (2008).

8. For an exemplary use of Gell’s model by a historian of art, see Tanner (2007: especially 90–91).

9. For a helpful distinction between ‘work’ and ‘text’, see Currie (2004: 25–26).

10. I am begging a lot of questions here about the relationship between digital facsimiles and physical copies. The important point is that digital technology has raised awareness of these copies, making them more visible to all students of literature.

11. For a still broader approach to the ways in which early modern Spanish artefacts index the will to memory and knowledge, see Bouza Alvarez (2004). There are various programmes that host this type of approach, including, for example, the ‘History of Text Technologies’ programme at Florida State University.

12. Gell has been criticized for not adequately or correctly distinguishing artistic indexes and their effects from non-artistic types (Layton 2003: 452, 459–61; Bowden 2004: 320–24). This is a problem in and for modern aesthetic theory. As early modern culture had not institutionalized ‘art’ as a separate domain of experience, I shall not address the problem here.

13. For early modern studies, the best example of a discourse of judgement in this sense is the language of ‘curiosity’ (Kenny 2004). Anthropological critics of Gell’s theory have pointed out that one needs to be able to reconstruct ‘indigenous, historically specific systems of value’ – or of attribution of value – in order to understand how agency is indexed in different ways in different cultures (Winter 2007).

14. For examples of this kind of information as registered in writing by a consumer of books, see the later journals of Pierre de L’Estoile (1948–60).

15. Bacon’s Latin translation of this passage contains no significant departures from the English original (1623: sigs. I3v-4r).

16. The comparison between the efficacy of the visual and literary arts had long been a commonplace; see Baxandall (1971: 88–92). It was, of course, possible to argue the opposite: that a book was but a copy of antiquity, whereas a material artefact like a medal was antiquity itself; see Wintroub (1997: 195, where the citation is from Henry Peacham).

17. In his own cosmology Bacon accepted the notion of seminal spirit-agents but did not give them the same scope of action they had in Paracelsus and Severinus (Shackleford 1998: 32 and notes 45, 46).

18. The following discussion of King James’s work (James VI and I 1603) draws upon and responds to Scott-Warren (2001: 4–11).

19. The online version of Tom Riddle’s diary can be found at http://pandorabots.com/pandora/talk?botid=c96f911b3e35f9e1, accessed 18 January 2010.

Bacon, F. (1605) 2000. The Advancement of Learning, ed. M. Kiernan. Oxford: Clarendon.

———. 1623. Opera Francisci Baronis de Verulamio . . . Tomus Primus: Qui Continet De Dignitate & Augmentis Scientiarum Libros IX. London: In Officina Ioannis Haviland.

Baxandall, M. 1971. Giotto and the Orators: Humanist Observers of Painting in Italy and the Discovery of Pictorial Composition, 1350–1450. Oxford: Clarendon.

Bouza Alvarez, F.J. 2004. Communication, Knowledge, and Memory in Early Modern Spain. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bowden, R. 2004. ‘A Critique of Alfred Gell on Art and Agency’, Oceania 74(4): 309–24.

Brett, A. 2002. ‘What is Intellectual History Now?’, in D. Cannadine (ed.), What is History Now? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 113–31.

Campbell, S. 2001. ‘The Captivating Agency of Art: Many Ways of Seeing’, in C. Pinney and N. Thomas (eds), Beyond Aesthetics: Art and the Technologies of Enchantment. Oxford: Berg, pp. 117–35.

Cave, T. (ed.). 2008. Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ in Early Modern Europe: Paratexts and Contexts. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Chartier, R. and A. Messerli (eds). 2000. Lesen und Schreiben in Europa 1500–1900: Vergleichende Perspektiven = Perspectives Comparées = Perspettive Comparate. Basel: Schwabe.

Clanchy, M.T. 1993. From Memory to Written Record, England 1066–1307. Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Crick, J.C. and A. Walsham (eds). 2004. The Uses of Script and Print, 1300–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Currie, G. 2004. Arts and Minds. Oxford: Clarendon.

Diefendorf, B.B. and C.A. Hesse (eds). 1993. Culture and Identity in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800): Essays in Honor of Natalie Zemon Davis. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Drakakis, J. 2001. ‘Cultural Materialism’, in C. Knellwolf, C. Norris and J. Osborn (eds), The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism Volume 9: Twentieth-Century Historical, Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–58.

Frasca-Spada, M. and N. Jardine (eds). 2000. Books and the Sciences in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fumaroli, M. 2002. L’Âge de l’Éloquence: Rhétorique et “Res Literaria” de la Renaissance au Seuil de L’époque Classique. Geneva: Droz.

Garrison, M. 1999. ‘ “Send More Socks”: On Mentality and the Preservation Context of Medieval Letters’, in M. Mostert (ed.), New Approaches to Medieval Communication. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 69–99.

Gell, A. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon.

———. 1999. The Art of Anthropology: Essay and Diagrams, ed. E. Hirsch. New Brunswick, NJ: Athlone Press.

Grafton, A. 2007. What Was History?: The Art of History in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Grafton, A. and A. Blair (eds). 1990. The Transmission of Culture in Early Modern Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Greenblatt, S. 1980. Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Halverson, J. 1992. ‘Goody and the Implosion of the Literacy Thesis’, Man 27(2): 301–17.

Horowitz, M.C. 1998. Seeds of Virtue and Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

James VI and I, King. 1603.  . Or His Maiesties Instructions to His Dearest Sonne, Henry the Prince. London: John Norton.

. Or His Maiesties Instructions to His Dearest Sonne, Henry the Prince. London: John Norton.

Jardine, L. 1974. Francis Bacon, Discovery and the Art of Discourse. London and New York: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1993. Erasmus, Man of Letters: The Construction of Charisma in Print. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jardine, L. and A. Grafton. 1990. ‘ “Studied for Action”: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy’, Past and Present 129: 30–78.

Johns, A. 1998. The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kenny, N. 2004. The Uses of Curiosity in Early Modern France and Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Küchler, S. 1987. ‘Malangan: Art and Memory in a Melanesian Society’, Man 22(2): 238–55.

———. 1988. ‘Malangan: Objects, Sacrifice and the Production of Memory’, American Ethnologist 15(4): 625–37.

———. 1992. ‘Making Skins: Malangan and the Idiom of Kinship in Northern New Ireland’, in J. Coote and A. Shelton (eds), Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 94–112.

L’Estoile, Pierre de. 1948–60. Journal Pour le Règne de Henri IV. 3 vols. Paris: Gallimard.

Layton, R. 2003. ‘Art and Agency: A Reassessment’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute Incorporating Man 9(3): 447–64.

McKitterick, D. 2003. Print, Manuscript, and the Search for Order, 1450–1830. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, H-J. 1994. The History and Power of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meskell, L. and R.W. Preucel. 2004. A Companion to Social Archaeology. Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell.

Mullett, M. 1990. ‘Writing in Early Mediaeval Byzantium’, in R. McKitterick (ed.), The Uses of Literacy in Early Mediaeval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 156–85.

Myers, R., M. Harris and G. Mandelbrote (eds). 2005. Owners, Annotators and the Signs of Reading. New Castle, DE and London: Oak Knoll Press and The British Library.

O’Connell, M. 2000. The Idolatrous Eye: Iconoclasm and Theater in Early-Modern England. New York: Oxford University Press.

Olson, D.R. 2004. ‘Knowledge and its Artifacts’, in K. Chemla (ed.), History of Science, History of Text. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic, pp. 231–45.

Pearson, D. 2007. ‘What Can We Learn by Tracking Multiple Copies of Books?’, in R. Myers, M. Harris and G. Mandelbrote (eds), Books on the Move: Tracking Copies through Collections and the Book Trade. New Castle, DE and London: Oak Knoll Press and The British Library, pp. 17–37.

Rainbow, E. 1677. A Sermon [on Prov. xiv. 1] Preached at the Funeral of . . . Anne Countess of Pembroke . . . With Some Remarks on the Life of that Lady. London: F. Royston and H. Broom.

Rampley, M. 2005. ‘Art History and Cultural Difference: Alfred Gell’s Anthropology of Art’, Art History 28(4): 524–51.

Richardson, B. 1999. Printing, Writers, and Readers in Renaissance Italy. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rowling, J.K. (1998) 1999. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. New York: Arthur A. Levine.

Salkeld, D. 2001. ‘New Historicism’, in C. Knellwolf, C. Norris and J. Osborn (eds), The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism Volume 9: Twentieth-Century Historical, Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 59–70.

Scott-Warren, J. 2001. Sir John Harington and the Book As Gift. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shackleford, J. 1998. ‘Seeds with a Mechanical Purpose’, in A.G. Debus and M.T. Walton (eds), Reading the Book of Nature: The Other Side of the Scientific Revolution. Kirksville, MO: Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers, pp. 16–44.

Sperber, D. and D. Wilson. 1995. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Tanner, J. 2007. ‘Portraits and Agency: A Comparative View’, in R. Osborne and J. Tanner (eds), Art’s Agency and Art History. Malden, MA: Blackwell, pp. 70–94.

Weel, A. van der. 2004. ‘Scripta Manent: The Anxiety of Immortality’, in J.F. v. Dijkhuizen (ed.), Living in Posterity: Essays in Honour of Bart Westerweel. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, pp. 321–32.

Weiner, J.F. 2001. ‘Romanticism, from Foi Site Poetry to Schubert’s Winterreise’, in C. Pinney and N. Thomas (eds), Beyond Aesthetics: Art and the Technologies of Enchantment. Oxford: Berg, pp. 13–30.

Whitney, Geffrey. 1586. A choice of emblemes, and other deuises, for the moste parte gathered out of sundrie writers, Englished and moralized. And diuers newly deuised, by Geffrey Whitney. A worke adorned with varietie of matter, both pleasant and profitable: wherein those that please, maye finde to fit their fancies: bicause herein, by the office of the eie, and the eare, the minde maye reape dooble delighte throughe holsome preceptes, shadowed with pleasant deuises: both fit for the vertuous, to their incoraging: and for the wicked, for their admonishing and amendment. Leiden: C. Plantin.

Winter, I.J. 2007. ‘Agency Marked, Agency Ascribed: The Affective Object in Ancient Mesopotamia’, in R. Osborne and J. Tanner (eds), Art’s Agency and Art History. Malden, MA: Blackwell, pp. 42–69.

Wintroub, M. 1997. ‘The Looking Glass of Facts: Collecting, Rhetoric and Citing the Self in the Experimental Natural Philosophy of Robert Boyle’, History of Science 35(108): 189–217.

Wolfe, J. 2004. Humanism, Machinery, and Renaissance Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.