CHAPTER 8

ART, PERFORMANCE AND TIME’S PRESENCE

Reflections on Temporality in Art and Agency

Eric Hirsch

[M]uch art consists of virtuosic performance, and . . . although the performances involved in most visual art take place, so to speak, ‘off-stage’, none the less a painting by Rembrandt is a performance by Rembrandt, and is to be understood only as such, just as if it were a performance by one of today’s dancers or musicians, alive and on-stage.

Alfred Gell – Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory

Introduction

Comparisons between Aboriginal Australian societies and the societies of Melanesia are long standing in anthropology. An example is the volume on ‘emplaced myth’, comparing and analysing the mythic narratives and ritual forms of the contiguous regions of Australia and New Guinea (Rumsey and Weiner 2001; cf. Wagner 1972). The comparisons in this case suggest a considerable period of spatial connection between areas where myths or ritual forms in Australia, for example, are the transformation of myths and ritual forms in New Guinea. For three-quarters of their period of human habitation they were a single landmass: ‘even in the postglacial period when the land bridge across the Torres Strait became inundated, the two have never been separated by more than sixty miles of open sea, across which there has probably always been continuous traffic’ (Rumsey 2001: 6–7).

Comparisons involving such neighbouring regions and their cultural and social forms are legion in anthropology – Lévi-Strauss’s monumental analysis of myth being perhaps the best known and celebrated. Comparisons between non-adjacent regions are also undertaken where the focus is narrowed to limited categories such as the body or person (Lambek and A. Strathern 1998) or that of gender (Gregor and Tuzin 2001). Here the comparison is not based on the assumption of spatial connection between societies and the potential mutual transformation of socio-cultural forms, but of ascertaining whether models that have informed analysis of, say, the body in one region have analytical purchase in another region. This is especially the case with categories that have become prominent in anthropology more generally. Strathern and Lambek (1998: 5) describe ‘ “[b]ody” [as] an operator-word used to give a layered semblance of unity to our anthropological discourse because of its supposed (etic [i.e. ‘cultural neutrality’]) universality’. In order to undertake such comparisons, it is necessary to agree on an accepted designation of the entity or entities being compared. The category of art is one that has proved especially difficult for anthropologists to define and compare, as it covers a potentially vast range of entities from painting, poetry and sculpture to ritual performance. As Layton (1991: 4–6) notes: ‘Art is a difficult phenomenon to define . . . because there is an imprecise boundary between art and non-art whose location seems often to shift according to fashion and ideology.’

In order to obviate this problem, Gell proposed that art objects or artworks (I use them interchangeably below as does Gell) should be considered analogous to persons, that is, entities with agency-like properties and the power to influence. Accordingly, any entity (or ‘index’; see below) that exhibits agency-like properties – one that motivates abductive inferences, cognitive interpretations, and so on – is thus person-like and can be defined as art (see Gell 1998: 27). Such an entity is what Gell refers to as the ‘index’. The index exists at the intersection of the artist and her/his causal milieu, and the patient or recipient and her/his causal milieu; that is to say, the index exists ‘where the sphere of agency overlaps with the sphere of patiency’ (ibid.: 38). Gell suggests an anthropological theory of art ‘in which persons or “social agents” are, in certain contexts, substituted for by art objects (ibid.: 5, emphasis removed). The intention of Gell’s theory is to break down the boundary between so-called ‘primitive’ or traditional art and that of ‘modern’ art. He also seeks to avert the boundary between art objects broadly defined and that of persons. In his book, Gell compares and juxtaposes art forms from diverse cultural and social contexts in order to illustrate the facets of art as agency; art analogous to agents.

Time’s Flow and Time’s Presence in the Comparative Analysis of Artworks

In this chapter, I compare anthropological interpretations of Australian Aboriginal (Yolngu) and Melanesian (Fuyuge) artworks in the tradition of comparison mentioned above, and incorporate into these comparisons art historical interpretations of artworks from different periods in Western art history (Alpers [1983] 1989; Clark 1985; Damisch [1987] 1995; Fried 1980; Krauss 1985; Snyder 1985). The chapter is framed by the Australian and Melanesian ethnographic accounts of artworks. Between these I briefly consider three art historical interpretations of artworks: Alpers’s ([1983] 1989) analysis of seventeenth-century Dutch art; Clark’s (1985) study of the ‘painting of modernity’ in Paris of the 1860s; and Fried’s monograph on mid-eighteenth-century French painting. I have chosen these cases because they are generally recognized as landmark studies in the art history field and because they intersect conceptually in unique ways with Gell’s concerns in Art and Agency. Although Gell does not refer to any of these authors, both Alpers and Fried foreground the relations between artist and recipient – Alpers analysing more specifically the causal environments of this relation while Fried considers the artistic strategies adopted and the effects these had on recipients. Clark’s Marxist-informed account has similar objectives to Gell’s anthropological theory of art: ‘to account for the production and circulation of art objects as a function of [the social] relational context’ (Gell 1998: 11).

Alpers’s ([1983] 1989) study is in the line of art historical analysis developed by Baxandall (1972) with its attention to the ‘period eye’. Gell (1998: 2) addresses this art historical approach in the opening pages of his book where he is critical of a focus on aesthetic systems, whether of a ‘cultural system’ or ‘historical period’. Nonetheless, her study assists us in understanding why the Dutch at the time, as much as Gell (1998: 69, 72) himself for different reasons, were captivated by these images, such as those created by Vermeer.

In contrast to Alpers’s study, Clark’s analysis (1985) focuses on the inextricable connections between artworks and social practice. In a sense, Clark’s study dovetails with Gell’s anthropological emphasis on the social and social relationships in particular (Gell 1998: 3). For Clark, the emphasis is on class relations and specifically how the ‘painting of modernity’, as his book calls it, reveals why and how the artists of the time were closely related with the interests and economic conventions of the bourgeoisie, and how this took form in the artworks they created.

Fried’s study is aligned in different ways to both Alpers’s and Clark’s studies. Like Alpers, Fried examines the complex relations between artists, recipients and paintings. His interest in representational ‘absorption’ parallels Alpers’s concern with ‘anti-Albertian’ representation evident in seventeenth-century Dutch art. Where the Albertian definition of the picture exists as ‘a framed surface or pane situated at a certain distance from a viewer who looks through it at a second substitute world’, anti-Albertian representation lacks such framing devices, and it is as if the world depicted came first (Alpers [1983] 1989: xix).

As with Gell’s study, Fried is interested in the effect that artworks – paintings in this case – may have on the recipient/beholder (cf. Krauss 1985: 3–4). But as Fried explores, this effect is a means of both negating the presence of the beholder, while simultaneously and paradoxically drawing the beholder to the artwork because her/his presence has been denied (cf. Pinney 2001: 157–60). At the same time, the relation between artist and critic (e.g. Diderot – eighteenth-century philosopher, art critic and writer) that first emerges in Fried’s study of mid-eighteenth-century French painting is transformed in the market-orientated, restructured urban context of Paris in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, documented by Clark.

I compare these different interpretations of artworks, from different contexts and periods, in order to illustrate Gell’s approach in treating all ‘art objects’ as potentially comparable and subject to analysis within a single framework. At the same time, there are limitations in this approach. Gell does not explicitly acknowledge that his theory assumes all societies are equivalently productive of ‘art’, although the form of this art may differ between them. What he also does not explicitly acknowledge are the regional differences influencing the creation of social and cultural forms, such as ‘art’, and how art forms can be the diverse outgrowths of unique, regional and historical processes.

Gell also largely ignores institutional differences in the comparisons he develops, such as the analogies he describes between Duchamp’s oeuvre – created in a dealership market – and that of Maori meeting houses, which were created in a colonial context (Gell 1998: 242–58). These differences are important to consider when comparing, as I do below, examples of European art (as analysed by art historians and art critics) with Melanesian and Australian Aboriginal examples (as analysed by anthropologists). They are important because ‘the network of relationships surrounding particular artworks in specific interactive settings’ (ibid.: 8) will differ depending on distinctive institutional contexts (cf. Berger 1972; Bourdieu [1979] 1984). In addition, in the concluding chapter of Art and Agency (1998) Gell develops the analogy between art objects and persons with respect to time. He suggests that art objects produced by an artist and forming her/his oeuvre exhibit a comparable expression of temporality to that of the artist’s own time consciousness.

It is here, in particular, that I draw attention to a dimension of time that is central to both Gell’s theory of art and agency, as well as diverse art historical analyses, but which is not explicitly addressed in Gell’s theory or the art historical examples. This is the dimension of time’s presence.

In the case of Gell’s theory, Husserl’s model of individual time-consciousness is drawn upon to conceptualize the temporality of indexes. Husserl’s model argues that the individual consciousness of the present is

not a knife-edge ‘now’ but a temporally extended field within which trends emerge out of the patterns we discern in the successive updatings of perceptions relating to the proximate past, the next most proximate past, and the next, and so on. This trend is projected into the future in the form of protentions, that is, anticipations of the pattern of updating of current perceptions which will be necessitated in the proximate future, the next most proximate future, and the next, in a manner symmetric with the past, but in inverse temporal order . . . The effect of this argument is to abolish the hard-and-fast distinction between the dynamic present and the fixed and unchanging past. (Gell 1998: 239–40)

Gell develops from this model the terminology used to consider indexes in an analogous way. With respect to artworks or indexes, Gell speaks of ‘strong and weak protentions for “prospective” or future-orientated relations, and strong and weak retentions for “retrospective” or past-orientated relations’ (Gell 1998: 235). If we consider the work of an individual artist or the collective work of a culture, ‘the arrangement of individual works in an artist’s oeuvre, each of which is partly a recapitulation of previous works and partly an anticipation of works as yet uncommenced, seems to generate the same kind of relationship between indexes (which are objects in the external world) as exist between mental states in the cognitive process we recognize as consciousness’ (ibid.: 236; emphasis removed). Gell argues, then, that the ‘temporal structure of index-to-index relations’ (i.e. objects related to each other in the external world) in an artist’s work, for example, ‘externalizes or objectifies the same type of relations as exist between the artist’s internal states of mind as a being endowed with consciousness’ (ibid.). As he indicates with reference to his analysis of Duchamp’s oeuvre, ‘[e]ach Duchamp work, in other words, invites us to adopt a particular perspective on all Duchamp’s works, often by providing explicit quotations or references to past and future works, though also adumbrating retentions and protentions in a more elliptical fashion’ (ibid.: 250).

What the focus on temporal passage overlooks, I contend, is that of temporal presence, that is to say, time as ‘now’; the temporal presence that is manifest by artworks as much as the actions of persons (giving a sense of occupying a distinctive ‘time’). Artworks are able to create this illusion of stoppage because the artistic performances they display materially evoke the moment in which they were created. The artworks provide a sense of the context and time in which it was possible to create such forms. Thus, different forms and styles of art objects will be evocative of different presences of time. Art historians, as I will discuss below, illustrate their arguments about a period, style or artist with artworks that are supposed to capture the artistic moment or epoch they are analysing. The artworks art historians deploy for these purposes disclose the ‘now’ that the artist or artists and their publics were to have experienced. The artwork or artworks appear to occupy a unique time.

Think for a moment about the telling of a myth, the performance of a ritual, or a created painting; the performance of each can be understood to occupy its own time. The actual interval of time can be very different – several minutes in the case of a narrative, several months for a ritual, several hours, days or weeks (of largely unseen activity in the Western context) for a painting. This dimension of time is what Wagner (1986: 81–82) refers to as organic time, where past and future are both subsumed within the present. The events or moments occurring in organic time – as evoked in a myth, ritual or painting – ‘have a definitive and non-arbitrary – a constitutive – relationship to the sequence as a whole’ (ibid.: 81). In the case of Western painting, for example, the evocation of organic time is, in a sense, indirect, as the actual performance of creating artworks is conventionally concealed.1 The viewing, assessment and analysis of paintings by beholders of various kinds (lay publics, critics, and so on) are the contexts in which time’s presence captured by a painting may be grasped.

In this light, a comment by the art historian and art critic Michael Fried (1982) is pertinent. It arose in the context of a debate about modernism in art with fellow art historian T.J. Clark (1982). Of the present form of modernism, Clark (1982: 156) was critical: ‘an art whose object is nothing but itself, which never tires of discovering that that self is pure as only pure negativity can be, and which offers its audience that nothing, tirelessly and, I concede, adequately made over into form’.

Fried responded with an assessment that is relevant, I think, to how the presence of time is potentially apprehended by painters and audience alike in relation to (modernist) Western painting:

[T]he modernist painter seeks to discover not the irreducible essence of all painting but rather those conventions which, at a particular moment in the history of the art, are capable of establishing his work’s nontrivial identity as painting leaves wide open (in principle though not in actuality) the question of what, should he prove successful, those conventions will turn out to be. (Fried 1982: 227, emphasis added)

Fried is suggesting that the modernist painter, through her/his artistic performance, seeks to discover and realize the conventions of painting that define the current moment or ‘now’ of artistic practice.

Gell’s model does not address the dimension of time concerned with its presence. By contrast, Gell’s (and Husserl’s) analysis of time consciousness and the recurrent transformations of temporal protentions and retentions provide a useful analogy when applied to ‘sets of related artworks’. It enables the mutual relations, influences and changes between sets of artworks to be discerned (see Gell 1998: 232–42). However, a focus on the temporal flow of artworks obscures what is the equally important aspect of organic time. Although both are concerned with temporality, there is a difference; and this difference is that a myth, ritual or painting makes something apparent or obvious. The significance made apparent by an art object is through the way it evokes a unique moment. Wagner (1986: 86) refers to this as ‘time that stands for itself’: it has the immediacy of perception, rather than the passage of time, that is perceived. Artworks can exhibit this quality because their realization potentially renders obvious a meaning or significance that appears to occupy its own time – its own ‘now’. We only need to think of iconic artworks, such as Picasso’s Guernica that conjure up the prelude to World War Two (as the Spanish Civil War) as much as an anti-war symbol about the tragedies of war more generally.

Although artworks have this potential quality, the quality is realized differently depending on context and audience. So, for example, in the Australian Aboriginal and Melanesian cases I consider, those who assess the artistic performances (body painting, ritual) are connected to the performers through relations of kinship and marriage. The concern of artistic performers as much as those assessing their performance is that the artistic creations conform to ancestral precedent. But how this ancestral precedent should appear at any given time is never certain and is subject to contest and debate among those creating or assessing the artwork. It is open to contest and debate because those involved can never be entirely certain of what the current moment is and how this ‘now’ is to be visibly manifest. Within particular ancestrally perceived constraints, creators of artworks attempt to appear effective in the way their creation is fabricated. In doing so they create a perception of ‘now’, of what is appropriate at the moment, which is taken as conventional or is contested.

By contrast, the post-Renaissance European art I consider is formed in very different sets of social relations. The connections between artists and beholders are not by and large informed by relations of kinship and marriage, and in most cases the beholders are unknown to the artist. The artists are increasingly less constrained by ancestral precedent and more constrained by changing conventions of artistic representation and changing relations between artist and audience of various kinds. But what are the appropriate artistic conventions at any given time and what should the relations be between artist and audience at any moment? Again, these can never be known for certain and are open to competing claims and contests. Artists, audiences and critics compete and debate to determine what artistic conventions should prevail ‘now’ and what artworks appear as evidence of this moment. The debate between Clark and Fried mentioned above was, among other matters, about this problem.

I take up these issues by first considering an Australian Aboriginal example of painting analysed by Morphy (1991, 2009). I draw on this case because Morphy also addresses various criticisms of Gell’s theory, and I consider these in relation to the ethnography Morphy presents. I then turn to the art historical examples and consider the ways in which art historians have analysed various styles and epochs of painting artworks. I highlight how they have either implicitly or explicitly used particular artworks to act as evidence of the temporal presence (e.g. nineteenth-century Parisian modernity) they are explicating. As with the Australian Aboriginal case interpreted by Morphy, the art historical examples illustrate how artworks distinctively render obvious time’s presence and how this is differently debated depending on the context and the artworks concerned. I then bring in my final comparison, an anthropological interpretation of an artwork from Melanesia – a ritual – where there is debate among the local denizens about how the ritual is to be manifest in the present. The ritual performance is an ‘index’ permitting the abduction of agency analogous to a painting where the ‘sphere of agency’ enacted by the ritual performers overlaps with the ‘sphere of patiency’ enacted by the audience of the ritual. As informs the opening Australian Aboriginal example, the debate here is framed in terms of ancestral concerns and not in terms of the category of ‘art’ or artistic progress, as in the art historical examples.

Meanings and Time of the Ancestral Past

As I have indicated, Gell’s theory of art ostensibly overlaps with the anthropological theory of the person (cf. M. Strathern 1988). In Art and Agency, he argues that persons or ‘social agents’ are in specific contexts substituted by ‘art objects’ (Gell 1998: 5). In formulating his theory, Gell takes issue with Morphy’s definition of art objects as ‘sign-vehicles, conveying “meaning” ’ (ibid.). In this view, Gell argues, art objects are analogous to a visual code for the communication of meaning, or made to elicit an ‘endorsed aesthetic response, or both of these simultaneously’ (ibid.). Instead of the emphasis on meaning advanced by Morphy, Gell ‘views art as a system of action intended to change the world rather than encode symbolic propositions’: the ‘ “action”-centred approach to art . . . is preoccupied with the practical mediatory role of art objects in the social process’ (ibid.: 6).

In a recent article, Morphy (2009) contests Gell’s assessment of the aesthetic and semantic dimensions of art objects. Morphy argues instead that it is precisely through the aesthetic and semantic aspects of objects ‘that artworks become indices of agency and indeed create the particular form of agency concerned’ (ibid.: 8). He develops this argument with respect to his ethnography of Yolngu initiation that I consider below. Morphy, however, agrees with Gell’s emphasis on art objects as mediating social agency: mediating domains of existence, mediating artists and audience, and ‘mediat[ing] between an object that they are an index of and the person interacting with that object’ (ibid.). In the example of eighteenth-century French painting that I draw on, art criticism at the time was concerned with the effect the painted representation had on the audience; the painting was meant to mediate explicitly the relationship between painter and beholder.

While Morphy agrees with Gell’s emphasis on art as a mode of action and less about ‘encoding symbolic propositions about the world’ (Morphy 2009: 14), he suggests ‘that in many cases the semantic component of art can be integral to its being a mode of acting in the world, which may be directed towards change or any other objective that motivates the person who uses it’ (ibid.). It is this issue in particular that he takes up in his ethnography.

Morphy’s focus on the semantic and aesthetic components of art as a mode of action is one I take up as well. He uses the ethnography of Yolngu body painting in initiation ceremonies to problematize the ‘isomorphy of structure’ suggested by Gell. By isomorphy of structure Gell refers to the similarity between ‘the cognitive processes we know (from inside) as “consciousness” and the spatio-temporal structures of distributed objects in the artefactual realm – such as the oeuvre of one particular artist (Duchamp . . .) or the historical corpus of types of artworks (e.g. Maori meeting houses)’ (Gell 1998: 222). Morphy argues instead that the focus needs to be on the creation of art in context, and the way supra-individual images are ‘produced by minds and imaginations of the interacting individuals’ (2009: 15). While I agree with Morphy’s emphasis on the context of the creation and use of art objects, what his analysis does not address is the component of time. Time is significant because ‘interacting individuals’ and the way art objects mediate their interactions happens, as I have indicated, in time. Interactions and mediations in time also potentially create a distinctive time – its presence and its meanings. This is evident in the ethnography that Morphy presents, to which I now turn.

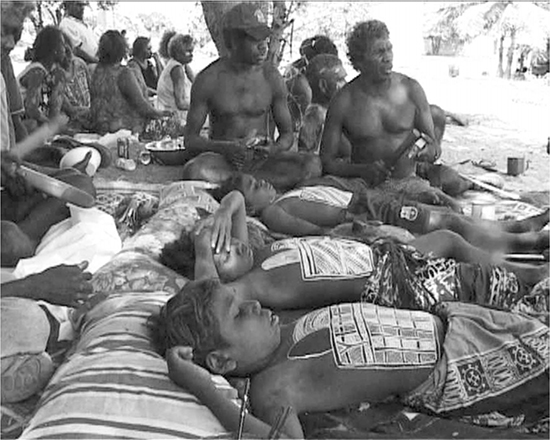

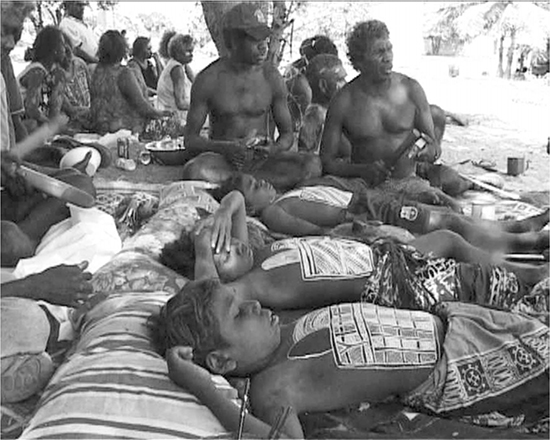

Morphy describes how the images painted on the Yolngu initiate’s chest are selected from images representing places associated with ancestral beings. These images are the important possessions of clans. The actual painting takes place on the day of the initiation circumcision. The painting process takes around four hours, and the initiate needs to remain motionless throughout. It must be completed by late afternoon, as the circumcision takes place just before sunset. ‘[T]he painting provides the focal point for the afternoon’s rituals, creating a set-aside space around which people sing and dance. The aesthetic effect of the painting is considerable and together with the feather armbands and dilly bags create the boys in the image of ancestral beings’ (Morphy 2009: 19). The artist and only a few other people may look directly at the painting before it is finished. After it is completed, the painting is exposed briefly to public inspection:

The painting exists as a much more widely connected and durable object than the instances of its production allow. Far from being disconnected from life it is linked everywhere to people and places. It exists in the mental archive that is Yolngu art and in the imaginations of the artists who can produce it on the occasions when it is required. The semantic dimension of the object is vital as far as Yolngu conceptions of the transmission of religious knowledge are concerned . . . The meanings encoded in the form of the paintings are referred to in many other contexts through the singing of clan songs and by observing features of the landscape, in the personal names that refer to the ancestral places that are represented in the paintings . . . (Morphy 2009: 16–17)

The performance, as Morphy describes it, occupies its own ‘time’. The ritual performers have a sense of what outcomes need to be achieved. What is rendered obvious is a meaning or significance, one that appears to occupy a distinctive time. The meaning is not necessarily spoken, but it is seen and recognized. As Morphy (2009: 15) indicates: ‘The main impact of the design may be through its aesthetic effect – the shimmering brilliance of the design which is relatively autonomous of its semantic meaning but which is interpreted as an index of ancestral power.’ The effect of the paintings and other ritual ornaments the boys wear ‘creates the boys in the image of ancestral beings’ (ibid.: 19).

More generally, ‘[p]aintings, dances, songs, and power names are collectively the mardayin, the sacred law through which knowledge of the ancestral past – the wangarr – is transmitted and reenacted’ (Morphy 1991: 292). In terms of Yolngu knowledge of sacred law and ancestral power, there are generally accepted sets of conventions for how the paintings should appear. Even where the designs and/or context alter, those producing the art objects ‘tend to deny that any innovations have occurred and to assert the continuity of an unchanging tradition’ (Morphy 2009: 20). It would seem from what Morphy indicates that the designs on petitions to Parliament, church panels and clan motor vehicles, among others, are all evidence of ‘time’s presence’, which in the Yolngu case is the time of ancestral power (ibid.). This is the case even where the designs have changed or the materials on which they are created are different from those used before colonial incursion. They are unique evocations of the ‘now’ of the ancestral past.

8.1 Body paintings on initiates at a Yolngu circumcision ceremony. The boys lie still for several hours while the designs are painted on their chests. They are surrounded by members of clans of their own moiety who sing songs that relate to the paintings that are being produced, referring to the journeys of the ancestral beings manifest in the images (see Morphy 2009: 16). Photograph: Howard Morphy.

Understanding the Current Moment Visually

In comparison to the Yolngu case I have just briefly considered, how is time’s presence evoked through artworks of the post-Renaissance European period, and how do art historians and others suggest this temporal existence through the artworks they deploy in their interpretations and arguments? This cannot be understood through the experience of artists and recipients in the present as anthropologists conventionally do, except possibly in those cases of fieldwork in contemporary art worlds (cf. Schneider and Wright 2010). Rather, art historians must draw on different sources, largely archival in nature. The frontpiece to The Order of Things (Foucault [1966] 1970) displays Velàzquez’s arresting image, Las Meninas. Foucault was not an art historian as such but he chose this artwork to introduce his study of the Western European ‘classical’ episteme. He analyses the image in detail, noting in particular, how the ‘entire picture is looking out at a scene for which it is itself a scene’ (ibid.: 14; Damisch [1987] 1994). Foucault chose this image, his analysis suggests, because it exemplifies in visual terms what he understood as the emergence of a new epoch or ‘now’ of ‘classical’ discourse and knowledge; a seventeenth-century emphasis on seeing and representation in contrast to the Renaissance stress on interpretation though resemblance: ‘Perhaps there exists, in this painting by Velàzquez, the representation as it were, of Classical representation, and the definition of the space it opens up to us’ (Foucault [1966] 1970: 16).

8.2 The Family of Felipe IV, or Las Meninas, by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1656). © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Whether Foucault’s analysis of the artwork is justified in the terms he suggests, what is of interest is the way he used the image to convey a new presence of time, evident in new forms of knowledge and representation. Foucault ([1966] 1970: 8) argues that the mirror in the painting ‘provides a metathesis of visibility that affects both the space represented in the picture and its nature as representation; it allows us to see, in the centre of the canvas, what in the painting is of necessity doubly invisible’. Others within and outside the art historical field have contested Foucault’s interpretation (cf. Searle 1980). Snyder (1985), an art historian, contests this understanding and suggests that the artwork may appear to be about the structure of appearance in painting. However, it uses this sort of engagement fostered by the painting to engender and endorse an ‘intimation of ideality’ (Snyder 1985: 564). He suggests that the artwork addresses the Infanta (at the centre, foreground of the painting) and the circumstances of her education: ‘[i]n a sense, Las Meninas is the painted equivalent of a manual for the education of the princess – a mirror of the princess [with the king and queen in the mirror at the centre, background, ruling over her]. In Snyder’s (ibid.: 559) analysis the mirror at the centre of the artwork is the ‘mirror of majesty’. According to Snyder (ibid.: 561) the image is not that of a new episteme (and the presence of time this evokes), but a representation of the time of the ‘perfect prince’ (ibid.: 561).

The debate here is, among other matters, about what constitutes a ‘visual culture’ (see Alpers [1983] 1989: xxv; Baxandall 1972) in any particular place and time, such as among the Yolngu above, and how this can be delineated and understood. Alpers ([1983] 1989: xxv) suggests that ‘[m]ost artistic traditions mark what persists and is sustaining, not what is changing, in culture’. The traditions exist and persist over periods of time (an epoch) and art historians (and anthropologists) use particular artworks to provide evidence and insights into the actual presence of this time.

In particular, Alpers accounts for the distinctive nature of Dutch visual culture in the seventeenth century. She highlights the intrinsic relations between interests in optical mechanisms and instruments, a privileging of vision, an impulse for maps and mapping, and the distinctiveness of the artworks created (e.g. Vermeer), as all elements of a more general value given to descriptive presence. She contrasts this northern tradition or aesthetic (an art of describing) with one of southern, Italian (Albertian) origins, where the emphasis is on narrative art; artworks associated with a textual source (Alpers [1983] 1989: xix).2 In the seventeenth-century Dutch context it is the relations between the diverse elements Alpers examines – artworks and other material entities – that were all being ‘simultaneously’ performed. Their meaning and aesthetic value derived from the sense of ‘now’ that these performances evoked.

Alpers’s ([1983] 1989: 8) analysis draws on Geertz’s (1976) understanding of art as a ‘cultural system’, where the cultural system – say in an area of Aboriginal Australia, Holland in the seventeenth century, or highland Papua, is locally specific. The influence of Geertz’s anthropological perspective – drawing on Baxandall’s (1972) influential account of the Italian fifteenth-century ‘period eye’ – emphasizes that beholders ‘both bring something to the interpretation of an art form, and expect something additional from it’ (O’Hanlon 1989: 138, emphasis removed). Here, artist and audience are in a kind of implicit dialogue about how the moment they currently occupy should be seen and understood.

Turning Points

But art can also be seen as a ‘turning point of culture’, evidence of a new temporal presence. This is the argument made by Clark (1985) in his study of painting in nineteenth-century Paris. He considers a different set of relations between artworks (indexes) and other entities and representations (such as class relations, spectacle and urban transformations) in Paris of the time, in order to disclose the sense of contemporaneousness evoked by Manet and his followers. Clark (ibid.: 32–33) argues that the actual, formal modernization of Paris accomplished by Haussmann in the 1860s and thereafter was foreseen thirty years earlier by the subtle changes occurring in buildings and residential shifts recorded by Victor Hugo and others. The plan and attempted realization of Paris’s modernization was thus anticipated like the completion of a myth; past and future subsumed within the present, which was the restructuring of the vast urban environment. Clark’s study examines the contested rhetoric that surrounded the new kind of painting at the time of urban modernization in conjunction with the finer details of the ‘Haussmannization’ of Paris. Haussmann attempted to provide an ideological or mythic unity to the city through his programme of radically transforming Parisian inhabitants, streets, housing, lighting, parks, and so on – rendering it into a ‘spectacle’ (ibid.: 63).3

The 1860s were an epoch of transition in the way the categories of social life (e.g. class, city, neighbourhood, sex, occupation) were understood and represented. It is the emergence of this new time and its vicarious visible presence that modernist artists sought to represent through their paintings and that Clark seeks to explicate through his detailed analysis of the artworks and their relationships to the urban setting of their creation. The focus of Clark’s analysis is the inextricable connection between social processes and social transformations – such as class and ideological struggle – and representations of various forms in the Paris of the 1860s, 1870s and thereafter (see Clark 1985: 261–66; in particular, his examination of Seurat’s Un Dimanche après-midi à lîle de La Grande Jatte in the concluding chapter). His study implicitly renders time’s presence apparent in this context by revealing these inseparable connections and their contradictions. The explicit focus of Clark’s study is the social and artistic struggles to represent this new urban context with its transformed class configuration, but in revealing this he simultaneously reveals the moment or ‘now’ through the range of artworks created to represent this moment.

Temporal Worlds of Representation

The period covered by the argument in The Painting of Modern Life saw the rise of the ‘dealer-critic system’ (Clark 1985: 260). Painters increasingly depended for their living on the movements of the world art market, and successful ones played one part of the market off another, changing their artistic practice to suit the needs of new contractual arrangements.

In contrast to the artistic situation documented by Clark, the relations between artist and audience were of a different nature prior to the collapse of the Ancien Regime in the late eighteenth century. In mid-eighteenth-century France there was a reaction against late Baroque or Rococo – a style of artistic representation that emphasized intimacy, sensuousness, and decoration, which was a revision of classical styles – and it is this movement that is the focus of Michael Fried’s study Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (1980). Fried’s study has a different theoretical orientation to that of Clark. As with Alpers’s ([1983] 1989) enquiry discussed above, he is interested in the specific relation between artist and beholder, and the anti-Albertian (i.e. absorptive) tendencies in post-Renaissance art. Like Alpers, he does not consider the artworks in the context of social processes and conflicts, but as indications of a distinctive visual culture.

A long-standing emphasis on absorption, of characters and/or action figuratively depicted being seemingly wholly absorbed in what is represented, was largely eclipsed during the period of Rococo. Critics and audience alike responded to a change in figuration that captured a new perceptual present, a ‘moment’ of visual culture distinct from the Rococo. There was debate at the time as to how absorption should be represented in paintings (see below) (Fried 1980: 108).

The reaction against Rococo is exemplified by the sensation caused when Greuze (1725–1805) exhibited his painting Père de Famille (1755). Several critics discussed the painting at length (Fried 1980: 8–10). The narratives reveal a specific concern with being ‘absorbed’ that the painting conveys through its representation of activity.4 A similar assessment by a contemporary critic reproduced by Fried is made for Chardin’s (1699–1779) earlier painting Un Philosophe Occupé de sa Lecture (1753).5

If we were to focus on Greuze (or, for example, Seurat in the previous section) and follow Gell’s (1998: 221–58) model of ‘distributed objects’ (i.e. the ‘objects’ of an artist or ‘culture’ distributed in space and time), we might consider Greuze’s oeuvre as a whole, and trace the ‘protentional’ and ‘retentional’ relationships between his works, seeing these as analogous to a form of individual time consciousness or durée exhibited by the artist (Gell 1998: 236). However, it is clear from the context in which Greuze produced his art (again, as with Manet, Monet, Seurat and others) that he was engaged in painting ‘in relation’ to other painters of the time such as Van Loo (1705–1765), Vien (1716–1809) and especially Chardin, as well as other audiences and under particular social conditions, as stressed by Clark.

The paintings occupy their own ‘absorptive time’, recognizable for their performance of this painterly convention. However, as Fried argues, a divergence emerged in the way absorption came to be represented and came to manifest the presence of this ‘absorptive time’. That is, between absorption as the hallmark of the everyday (Chardin) and absorption as ‘secondary’ to more theatrical (southern or Albertian, after Alpers) concerns (Greuze) (Fried 1980: 61; cf. Baxandall 1985: 74–104). This divergence supports Fried’s (ibid.: 61) claim that Chardin and Greuze ‘represent different worlds’. In other words, different expectations between artist and audience about what each came to expect from the other at this moment. The loss of the everyday in pictorial representation was a significant turning point – a shift in time’s presence manifest in painting in this period.6

In What Time Are We Now?

I now turn to my final example. It is from the Fuyuge people of Papua New Guinea with whom I have conducted fieldwork, and is different from the previous examples in that it deals not with painting – whether on-stage or off-stage – but with another kind of artwork and performance, that of ritual. It is appropriate to compare this artwork with the others considered as the creators/performers of the ritual understand it as having agency and the capacity to affect the audience, as much as themselves, in powerful ways. In this sense, it is an ‘index’ – following Gell’s terminology – that permits the ‘abduction of agency’. As with the Australian Aboriginal example, the ritual performances of the Fuyuge are meant to evoke an ancestral presence. And as with the Australian Aboriginal example, how this is meant to appear at any given performance is open to contest and debate. In that sense, my final example can also somewhat obliquely be compared to the mid-eighteenth-century French painting as the Fuyuge contest I describe implies the existence of ‘different worlds’, and how artworks (ritual performances) are meant to appear at a given moment. The ‘worlds’ in the Fuyuge case are not those of ‘absorption’ and ‘theatricality’ (or a northern and southern European artistic traditions) but those of imagined black people (Papua New Guineans) and imagined white people. Both peoples, it is understood from the Fuyuge perspective, derive ultimately from a single Fuyuge ancestral source (tidibe), although they currently exist as separate.

Fuyuge social life is focused on the performance of a ritual they call gab that consists of life-cycle rites, ceremonial exchanges, dances and pig killings. The ritual consists of a sequence of performances; each ritual unfolds in a specially built village and plaza, also known as gab. Dances are performed by one or more neighbouring collectives that are challenged to display their capacities in the ritual plaza. The dances are performed before the life-cycle rites, and the performance of those rites are then followed by different sets of pig killings; a great pig-killing performance caps the ritual as a whole.

It has been a long-standing convention among the Fuyuge that when two collectives of dancers perform, each can use different instruments, such as hand-held drums or large bamboo poles that are pounded on the ground. However, in the late 1990s, dancers in gab began to perform as ‘disco’.7 ‘Disco’ in this case refers to string-band music accompanied by a ‘stereotypical Polynesian dance, with swaying hips and undulating hand movements’ (Niles 1998: 78). This dance is performed centrally by young women, while small groups of young men parade about them, some playing guitars with amplifiers. They all perform songs that have string-band melodies with Fuyuge lyrics. Youth groups had performed this form of dance in the mid-1980s, but never in the context of a gab performance. The performance of disco in gab in 1999 was an innovatory act, as Gell (1998: 256) describes, but such acts are only innovatory from an anterior perspective, and this accounts for the importance of anticipation in gab. It was a political act meant to have the anticipated outcome of triumph over the other performers. But every gab is innovatory in this way, analogous to the creation of the Maori meeting houses that Gell (ibid.: 251–58) analyses.

8.3 Esa u kum women dancing disco kere at Hausline village. Photograph: Eric Hirsch.

8.4 Migu performing kere in conventional manner at Hausline village. Photograph: Eric Hirsch.

The particular gab I am concerned with is one that I observed and recorded during fieldwork in 1999. At this gab, one collectivity known as Esa u kum or EK (as shortened locally), performed as disco. The second collectivity challenged to perform, known as Migu, performed with drums. The ensuing evaluations and debates about their performances revealed, among other significant matters, important differences in Fuyuge ideas about the presence of time.

Shortly after the performance of EK, talk began to focus on the lower-body decorations of the dancers and their inferior appearance, particularly when compared to the powerful appearance created by Migu. The skin of the EK dancers did not look appropriately prepared; many were wearing shorts instead of loincloths. People said that from the shoulders up they were fine, but below that they looked as though they had rushed their preparations. This sentiment was reinforced by the reception that Migu received when they performed. It has long been customary for older and more highly regarded men to speak words of praise when they are impressed with the dancers, but there was silence during Migu’s performance. This is because everyone knew Migu was superior and they did not want to shame EK explicitly. However, these were not the only opinions I heard about Migu’s performance. Different views were subtly expressed later when the pigs for the life-cycle rites were killed and then distributed. There were also formal speeches in which attempts were made to capture the moment and the way in which the dancers had been perceived.

For example, one of the hosts who had invited EK to perform made a speech that attempted to ‘mask’ EK’s poor performance. The speaker stood on several dead pigs that were lined up, holding a head-dress decorated with feathers in one hand and a ten kina8 note in the other:

This is my power [showing the head-dress]; this is the white man’s power [showing the K10 note]. Mine is gone. I am not going to bring it back: Papua New Guinea and Australia, our power [money]. This is your flower. Get this thing and when anybody wants to cook his pumpkin [i.e. make a gab] and invites you, you get this and go. And if he asks you to go and play guitar you get this and lead your people and go. This one is at the back of me now [i.e. head-dress].

The speaker is saying that money and disco, associated as they are with white people, are the power of the future. A head-dress made on its own is not enough, is inadequate, and behind us now. He was claiming that the performance of EK, contrary to appearances, was powerful and one to be followed. By contrast, the performance of Migu, although seen as superior, was in fact not the power it appeared to be.

But his attempt to capture the moment did not go unchallenged. Shortly afterwards, another of the hosts held up a similar head-dress and money and began his speech:

This is white’s thing, this is our, black’s thing. I am not going to throw one and hold onto the other. The two will go up together [his two index fingers pointing together]. Sometime in the future the white man will tell me, show me your traditional ways dancing. If I leave custom and the white man asks me to show him in the future, what will I show him? [He says]: ‘You dance your “custom” ’, and what will I do? I might look for ways. ‘Law’ [money] and custom must go together.

The speaker is saying that both things, white and black, must proceed together. He is stating that one cannot have money without custom.

This debate about how the dancers did and should appear is simultaneously a debate about the presence of time. The debate was asking: in what time are we (Fuyuge) now, that of disco/money or that of custom? The performers and audience of gab all have a sense of the way in which the sequence of performances constituting gab is meant to become visible. The performances exhibit an ‘organic time’ as there is a definitive and non-arbitrary relationship between each sequence and the sequence as a whole. This is what the debate above is about: how the respective dancers should become visible and whether they appropriately fit into the performed whole as imagined.

In this sense, gab makes evident both the passage of time – the movement from one sequence of gab to the next – and the presence of time, the perception of ‘now’ created by the non-arbitrary relations of the entire sequence. Temporal passage and temporal presence are complementary and contiguous. Both passage and presence are visibly manifest in gab and in the Yolngu initiation ceremonies. It will be recalled that the painting on the Yolngu boys’ bodies prior to the circumcision requires that they remain motionless, and that the painting is the focal point of the ritual sequence. However, few people actually look at the paintings themselves until they are briefly, publicly displayed when completed. The temporal passage of the ritual coexists with the perception that the ritual as a whole creates or should create the young boys into the image of ancestral beings.

Conclusion

It will be recalled that the intention of Art and Agency is not only to remove the boundary between ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ art, but also to erase the boundary between artworks, broadly defined, and that of persons. Gell compares and juxtaposes artworks from diverse contexts to elucidate his art as agency model. I have followed Gell’s comparative example through examining interpretations of artworks by anthropologists and art historians, with specific reference to issues of temporality addressed in Art and Agency. Thus, in contrast to the Fuyuge and Yolngu examples that have framed my account, the European artworks analysed by art historians do not disclose the temporal passage that resulted in their creation. The ‘ritual’ of their creation is, as Gell (1998: 95) suggests ‘off-stage’ and is potentially implied or implicitly evoked by the completed image itself.

The European cases highlight the importance of the named, individual agency of the artist as potentially bound up with the perceived power and value of the painting. There is a contrast between these examples and that of the Yolngu and Fuyuge cases where the ‘artists’ are seen as vehicles for the creation of images that evoke ancestral power. The capacity of performers to create the intended effect on the audience is bound up with the (innovatory) reproduction of an ancestral pattern and not with individually recognized forms of representation. In the Yolngu and Fuyuge cases, the name and agency of the artists are not crucial – only that they can appropriately create the imagery of ancestral power.

Fuyuge gab and Yolngu initiation each generates its own (contested) aesthetic; and in each, meaning is created by the distinctive, ancestral time rendered apparent by the performances. The European cases are a painterly one like the Yolngu example, and the final French case is also a contest about the different worlds of painterly performance – a contest about artistic representation and the distinctive time and meaning manifest by absorption or theatricality. The Fuyuge example highlights a contest about the different imagined worlds (black and white) informing aspects of gab performance and time’s presence that each potentially manifests.

Where Gell considers the temporality of art objects, he has focused on them as specifically analogous to time consciousness, as durée, the passage of time. I have stressed a complementary and distinctive perspective, that of time’s presence. The importance of aesthetics and meaning are evident when this distinctive time perspective is considered, as we have seen above. Just as art objects, as broadly defined by Gell, are both conventional and innovatory (but not in any absolute sense), so art and persons render apparent time’s presence. Art and persons disclose the meanings and aesthetics that we attribute to lives lived in diverse forms of (temporal) performance.

Acknowledgements

I thank the editors of this volume, Liana Chua and Mark Elliot, for their invitation to the inspiring symposium where Gell’s Art and Agency was assessed ten years after its publication, and for their extremely helpful comments on various drafts of this chapter. I also thank the publisher’s two anonymous readers for their incisive comments. An early version of this chapter was presented to the Melanesian Research Seminar at the British Museum where I received some very insightful questions and suggestions for its improvement. Nick Stanley in particular directed my attention to Velàzquez’s Las Meninas and to some of the critical commentary that has emerged around understanding this artwork. Karen Richards gave a later draft of the chapter the benefit of her critical eye that greatly improved it. I only have myself to thank for any errors in fact or form that remain.

Notes

1. However, the prolific eighteenth-century artist Canaletto (1697–1768) had to revert to public performances of his painting when his later works were accused of being created by an impostor. Canaletto had to demonstrate that the temporal passage of his painting ‘ritual’, as conventionally performed ‘off-stage’, could result in his unique and distinctive representations. His images represent a topography (Venice, London) that simultaneously captures the perception of this topography at a unique moment, the perception of an eminently recognizable presence of time.

2. In the course of her analysis Alpers briefly discusses Velàzquez’s Las Meninas and underscores how it exemplifies both the southern and northern traditions of artistic representation. Unlike Foucault’s analysis that considers representation as a singular phenomenon, Alpers ([1983] 1989: 70) emphasizes two modes and indicates how Las Meninas ‘confounds a single reading because it depends on and holds in suspension two contradictory (but to Velàzquez’s sense of things, inseparable) ways of understanding the relationship of a picture, and of the viewer, to the world’. The ambiguity for beholders the picture generates is linked to the way the artwork registers a temporal presence in two different traditions of artistic representation.

3. The artists of this period, in particular Manet, can be understood to both represent this conquest of spectacle and modernity in some artworks (L’Exposition Universelle de 1867), while in others to show the resilience of older social conventions in the transformed urban context (La Musique aux Tuileries) – see Clark 1985: 64–66.

4. Fried reproduces the texts of critics from the time of the exhibition at the Salons. The following is a text of one of these critics:

A father is reading the Bible to his children. Moved by what he has just read, he is himself imbued with the moral he is imparting to them; his eyes are almost moist with tears. His wife, a rather beautiful woman whose beauty is not ideal but of a kind that can be encountered in people of her condition, is listening to him with that air of tranquillity enjoyed by an honest woman surrounded by a large family that constitutes her sole occupation, her pleasures, and her glory. Next to her, her daughter is astounded and grieved by what she hears. The older brother’s facial expression is as singular as it is true. The little boy, who is making an effort to grab things that he cannot understand, is perfectly true to life. Do you not see how he does not distract anyone, everyone being too seriously occupied? What nobility and what feeling in this grandmother who, without turning her attention from what she hears, mechanically restrains the little rogue who is making the dog growl! Can you not hear how he is teasing it by making horns at it? What a painter! What a composer! (Fried 1980: 9–10)

5. ‘This character is rendered with much truth. A man wearing a robe and fur-lined cap is seen leaning on a table and reading very attentively a large volume bound in parchment. The painter has given him an air of intelligence, reverie, and obliviousness that is infinitely pleasing. This is a truly philosophical reader who is not content merely to read, but who mediates and ponders, and who appears so deeply absorbed in his mediation that it seems one would have a hard time distracting him’ (Fried 1980: 10).

6. The shift away from the everyday also foreshadowed the re-emergence of absorption several decades later in the paintings of Courbet (1819–1877), who is associated with the advent of ‘realism’ in painting, and in what is now called ‘modern’ art. This shift in painterly representation saw Courbet attempt to ‘ “transport” himself bodily into his paintings, and thus in imagination to obliterate the painter-spectator who stands separate from the canvas as notional viewer of the scene it represents’ (Harrison 1994: 226). Again, it is recognizable because of how this renders apparent a new representational and temporal performance (cf. Nochlin [1971] 1990: 31).

7. The material that follows reworks and elaborates upon Hirsch 2001.

8. The kina is the national currency of Papua New Guinea. As of October 2010, 1 kina = £0.24

References

Alpers, S. (1983) 1989. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century.

London: Penguin.

Baxandall, M. 1972. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 1985. Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Berger, J. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin.

Bourdieu, P. (1979) 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. R. Nice. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Clark, T. 1982. ‘Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art’, Critical Inquiry 9: 139–56.

———. 1985. The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers. London: Thames and Hudson.

Damisch, H. (1987) 1995. The Origin of Perspective, trans. J. Goodman. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Foucault, M. (1966) 1970. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Tavistock/Routledge.

Fried, M. 1980. Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1982. ‘How Modernism Works: A Response to T.J.Clark’, Critical Inquiry 9: 217–34.

Geertz, C. 1976. ‘Art as a Cultural System’, Modern Language Notes 91: 1473–99.

Gell, A. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gregor, T. and D. Tuzin (eds). 2001. Gender in Amazonia and Melanesia: An Exploration of the Comparative Method. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Harrison, C. 1994. ‘The Effects of Landscape’, in W. Mitchell (ed.), Landscape and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 203–39.

Hirsch, E. 2001. ‘New Boundaries of Influence in Highland Papua: “Culture”, Mining and Ritual Conversions’, Oceania 71: 298–312.

Krauss, R. 1985, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lambek, M. and A. Strathern (eds). 1998. Bodies and Persons: Comparative Perspectives from Africa and Melanesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Layton, R. (1981) 1991. The Anthropology of Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morphy, H. 1991. Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 2009. ‘Art as a Mode of Action: Some Problems with Gell’s Art and Agency’, Journal of Material Culture 14: 5–27.

Niles, D. 1998. ‘Papua New Guinea: An Overview’, in S. Cohen (ed.), International Encyclopaedia of Dance. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 76–78.

Nochlin, L. (1971) 1990. Realism. London: Penguin Books.

O’Hanlon, M. 1989. Reading the Skin: Adornment, Display and Society among the Wahgi. London: British Museum.

Pinney, C. 2001. ‘Piercing the Skin of the Idol’, in C. Pinney and N. Thomas (eds), Beyond Aesthetics: Art and the Technologies of Enchantment. Oxford: Berg, pp. 157–79.

Rumsey, A. 2001. ‘Introduction’, in A. Rumsey and J. Weiner (eds), Emplaced Myth: Space, Narrative, and Knowledge in Aboriginal Australia and Papua New Guinea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 1–18.

——— and J. Weiner (eds). 2001. Emplaced Myth: Space, Narrative, and Knowledge in Aboriginal Australia and Papua New Guinea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Schneider, A. and C. Wright (eds). 2010. Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice. Oxford: Berg.

Searle, J. 1980. ‘Las Meninas and the Paradoxes of Pictorial Representation’, Critical Inquiry 6: 477–88.

Snyder, J. 1985. ‘Las Meninas and the Mirror of the Prince’, Critical Inquiry 11: 539–72.

Strathern, A. and M. Lambek. 1998. ‘Introduction – Embodying Sociality: Africanist-Melanesianist Comparisons’, in M. Lambek and A. Strathern (eds), Bodies and Persons: Comparative Perspectives from Africa and Melanesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–25.

Strathern, M. 1988. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wagner, R. 1972. Habu: The Innovation of Meaning in Daribi Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1986. Symbols that Stand for Themselves. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.