5

Palliative Care & Pain Management

Michael W. Rabow, MD

Steven Z. Pantilat, MD

Ann Cai Shah, MD

Lawrence Poree, MD, MPH, PhD

Scott Steiger, MD

PALLIATIVE CARE

DEFINITION & SCOPE

Palliative care is medical care focused on improving quality of life for people living with serious illness. Serious illness is defined as “a condition that carries a high risk of mortality, negatively impacts quality of life and daily function, and/or is burdensome in symptoms, treatments or caregiver stress.” Palliative care addresses and treats symptoms, supports patients’ families and loved ones, and through clear communication helps ensure that care aligns with patients’ preferences, values, and goals. Near the end of life, palliative care may become the sole focus of care, but palliative care alongside cure-focused treatment or disease management is beneficial throughout the course of a serious illness, regardless of its prognosis.

Palliative care includes management of physical symptoms, such as pain, dyspnea, nausea and vomiting, constipation, delirium, and agitation; emotional distress, such as depression, anxiety, and interpersonal strain; and existential distress, such as spiritual crisis. While palliative care is a medical subspecialty recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (“specialty palliative care”) and is typically provided by an interdisciplinary team of experts, all clinicians should have the skills to provide “primary palliative care” including managing pain; treating dyspnea; identifying mood disorders; communicating about prognosis and patient preferences for care; and helping address spiritual distress. The fourth edition of the National Consensus Project’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care emphasizes that palliative care is the responsibility of all clinicians and disciplines caring for people with serious illness, in all health care settings (including hospitals, primary care and specialty clinics, nursing homes, and the community).

The scope of “generalist” palliative care and the ideal timing to begin “specialized” palliative care for patients with different illnesses is an evolving area of practice.

During any stage of illness, patients should be screened routinely for symptoms. Any symptoms that cause significant suffering are a medical emergency that should be managed aggressively with frequent elicitation and reassessment as well as individualized treatment. While patients at the end of life may experience a host of distressing symptoms, pain, dyspnea, and delirium are among the most feared and burdensome. Management of these common symptoms is described later in this chapter. Randomized studies have shown that palliative care provided alongside disease-focused treatment can improve quality of life, promote symptom management, and even prolong life.

Gärtner J et al. Early palliative care: pro, but please be precise! Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(1–2):11–18. [PMID: 30685764]

Krikorian A et al. Patient’s perspectives on the notion of a good death: a systematic review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Jan;59(1):152–64. [PMID: 31404643]

Mechler K et al. Palliative care approach to chronic diseases: end stages of heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver failure, and renal failure. Prim Care. 2019 Sep;46(3):415–32. [PMID: 31375190]

Ruiz M et al. Role of early palliative care interventions in hematological malignancies and bone marrow transplant patients: barriers and potential solutions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018 Nov;35(11):1456–60. [PMID: 29699418]

Schuler US. Early integration of palliative and oncological care: con. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(1–2):19–24. [PMID: 30572330]

Zhou K et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Herz. 2019 Aug;44(5):440–4. [PMID: 29468259]

PALLIATION OF COMMON NONPAIN SYMPTOMS

DYSPNEA

Dyspnea is the subjective experience of difficulty breathing and may be characterized by patients as tightness in the chest, shortness of breath, breathlessness, or a feeling of suffocation. Up to half of people at the end of life may experience severe dyspnea.

Treatment of dyspnea is first directed at the cause (see Chapter 9) if a workup is consistent with the patient’s goals. At the end of life, dyspnea responds to opioids, which have been proven effective in multiple randomized trials. Starting doses are typically lower than would be necessary for the relief of moderate pain. Immediate-release morphine given orally (2–4 mg every 4 hours) or intravenously (1–2 mg every 4 hours) treats dyspnea effectively. Sustained-release morphine given orally at 10 mg daily is safe and effective for most patients with ongoing dyspnea. Supplemental oxygen may be useful for the dyspneic patient who is hypoxic. However, a nasal cannula and face mask are sometimes not well tolerated, and fresh air from a window or fan may provide relief for patients who are not hypoxic. Judicious use of noninvasive ventilation as well as nonpharmacologic relaxation techniques, such as meditation and guided imagery, may be beneficial for some patients. Benzodiazepines may be useful adjuncts for treatment of dyspnea-related anxiety.

NAUSEA & VOMITING

Nausea and vomiting are common and distressing symptoms. As with pain, the management of nausea may be optimized by regular dosing and often requires multiple medications targeting the four major inputs to the vomiting center (see Chapter 15).

Vomiting associated with opioids is discussed below. Nasogastric suction may provide rapid, short-term relief for vomiting associated with constipation (in addition to laxatives), gastroparesis, or gastric outlet or bowel obstruction. Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide (5–20 mg orally or intravenously four times a day), can be helpful in the setting of partial gastric outlet obstruction. Transdermal scopolamine (1.5-mg patch every 3 days) can reduce peristalsis and cramping pain, and H2-blocking medications can reduce gastric secretions. High-dose corticosteroids (eg, dexamethasone, 20 mg orally or intravenously daily in divided doses) can be used in refractory cases of nausea or vomiting or when it is due to bowel obstruction or increased intracranial pressure. Malignant bowel obstruction in people with advanced cancer is a poor prognostic sign and surgery is rarely helpful.

Vomiting due to disturbance of the vestibular apparatus may be treated with anticholinergic and antihistaminic agents (including diphenhydramine, 25 mg orally or intravenously every 8 hours, or scopolamine, 1.5-mg patch every 3 days).

Benzodiazepines (eg, lorazepam, 0.5–1.0 mg given orally every 6–8 hours) can be effective in preventing the anticipatory nausea and anxiety associated with chemotherapy. For emetogenic chemotherapy, therapy includes combinations of 5-HT3-antagonists (eg, ondansetron, granisetron, dolasetron, or palonosetron), neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists (eg, aprepitant, fosaprepitant, or rolapitant), the N-receptor antagonist netupitant combined with palonosetron (NEPA), olanzapine, dexamethasone, and prochlorperazine. In addition to its effect on mood, mirtazepine, 15–45 mg orally nightly, may help with nausea and improve appetite. Finally, dronabinol (2.5–20 mg orally every 4–6 hours) can be helpful in the management of nausea and vomiting. Patients report relief from medical cannabis, although the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD) strains that are most effective remain unclear.

CONSTIPATION

Given the frequent use of opioids, poor dietary intake, physical inactivity, and lack of privacy, constipation is a common problem in seriously ill and dying patients. Clinicians must inquire about any difficulty with hard or infrequent stools. Constipation is an easily preventable and treatable cause of discomfort, distress, and nausea and vomiting (see Chapter 15).

Constipation may be prevented or relieved if patients can increase their activity and their intake of fluids. Simple considerations, such as privacy, undisturbed toilet time, and a bedside commode rather than a bedpan may be important for some patients.

A prophylactic bowel regimen with a stimulant laxative (senna or bisacodyl) should be started when opioid treatment is begun. Table 15–4 lists other agents (including osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol and lactulose) that can be added as needed. Docusate, a stool softener, is not recommended because it does not add benefit beyond stimulant laxatives in well-hydrated patients. Peripherally acting mu-receptor antagonists (including the oral agents naloxegol and naldemedine, and the subcutaneous methylnaltrexone) are recommended to treat opioid-induced constipation in laxative-refractory opioid-induced constipation. Evidence is insufficient to recommend lubiprostone or prucalopride for opioid-induced constipation. Patients who report being constipated and then have diarrhea typically are passing liquid stool around impacted stool.

FATIGUE

Fatigue, a distressing symptom, is the most common complaint among people with cancer. Specific abnormalities that can contribute to fatigue, including anemia, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, cognitive and functional impairment, and malnutrition, should be corrected if possible (and desired by the patient). Because pain, depression, and fatigue often coexist, pain and depression should be managed appropriately in patients with fatigue. Fatigue from medication adverse effects and polypharmacy is common and should be addressed. For nonspecific fatigue, exercise and physical rehabilitation are safest and may be most effective. Although commonly used, strong evidence is lacking for psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate, 5–10 mg orally in the morning and afternoon, or modafinil, 200 mg orally in the morning, for cancer-related fatigue. American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) has been shown to be effective for cancer-related fatigue but may have an estrogenic effect. Corticosteroids may have a short-term benefit. Caffeinated beverages can help.

DELIRIUM & AGITATION

Many patients die in a state of delirium—a waxing and waning in level of consciousness and a change in cognition that develops over a short time and is manifested by misinterpretations, illusions, hallucinations, sleep-wake cycle disruptions, psychomotor disturbances (eg, lethargy, restlessness), and mood disturbances (eg, fear, anxiety). Delirium may be hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed. Agitated delirium at the end of life has been called terminal restlessness.

Some delirious patients may appear “pleasantly confused,” although it is difficult to know what patients experience. In the absence of obvious distress in the patient, a decision by the patient’s family and the clinician not to treat delirium may be considered. More commonly, however, agitated delirium at the end of life is distressing to patients and family and requires treatment. Delirium may interfere with the family’s ability to interact with the patient and may prevent a patient from being able to recognize and report important symptoms. Common reversible causes of delirium include urinary retention, constipation, anticholinergic medications, and pain; these should be addressed whenever possible. There is no evidence that dehydration causes or that hydration relieves delirium. Careful attention to patient safety and nonpharmacologic strategies to help the patient remain oriented (clock, calendar, familiar environment, reassurance and redirection from caregivers) may be sufficient to prevent or manage mild delirium. A randomized trial of placebo compared to risperidone or haloperidol in delirious patients demonstrated increased mortality with neuroleptics. Thus, neuroleptic agents (eg, haloperidol, 1–10 mg orally, subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or intravenously twice or three times a day, or risperidone, 1–3 mg orally twice a day) generally should be avoided. When delirium is refractory to other treatments and remains intolerable, especially at the end of life, neuroleptic agents or frank sedation may be required to provide relief.

Adeboye OO et al. Nonpain symptom management. Prim Care. 2019 Sep;46(3):335–51. [PMID: 31375185]

Chen YJ et al. Exercise training for improving patient-reported outcomes in patients with advanced-stage cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Mar;59(3):734–49. [PMID: 31546002]

Kleckner AS et al. Opportunities for cannabis in supportive care in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019 Aug 1;11:1758835919866362. [PMID: 31413731]

Rao VL et al. Medical management of opioid-induced constipation. JAMA. 2019 Dec 10;322(10):2241–2. [PMID: 31682706]

Sorathia L. Palliative care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Clin North Am. 2019 May;103(3):517–26. [PMID: 30955518]

CARE OF PATIENTS AT THE END OF LIFE

In the United States, more than 2.8 million people die each year. Caring for patients at the end of life is an important responsibility and a rewarding opportunity for clinicians. From the medical perspective, the end of life may be defined as that time when death—whether due to terminal illness or acute or chronic illness—is expected within hours to months and can no longer be reasonably forestalled by medical intervention. Palliative care at the end of life focuses on relieving distressing symptoms and promoting quality of life (as in all other stages of illness). For patients at the end of life, palliative care may become the sole focus of care.

Emanuel EJ. The status of end-of-life care in the United States: the glass is half full. JAMA. 2018 Jul 17;320(3):239–41. [PMID: 30027232]

Prognosis at the End of Life

Prognosis at the End of Life

Clinicians must help patients understand when they are approaching the end of life. Most patients, and their family caregivers, want accurate prognostic information. This information influences patients’ treatment decisions, may change how they spend their remaining time, and does not negatively impact patient survival. One-half or more of cancer patients do not understand that many treatments they might be offered are palliative and not curative.

While certain diseases, such as cancer, are more amenable to prognostic estimates regarding the time course to death, the other common causes of mortality—including heart disease, stroke, chronic lung disease, and dementia—have more variable trajectories and difficult-to-predict prognoses. Even for patients with cancer, clinician estimates of prognosis are often inaccurate and generally overly optimistic. The advent of new anticancer treatments including immunotherapy and targeted therapies has made prognosis more challenging in some cancers. Nonetheless, clinical experience, epidemiologic data, guidelines from professional organizations, and computer modeling and prediction tools (eg, the Palliative Performance Scale or http://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/index.php) may be used to help offer patients more realistic estimates of prognosis. Clinicians can also ask themselves “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” to determine whether a discussion of prognosis would be appropriate. If the answer is “no,” then the clinician should initiate a discussion. Recognizing that patients may have different levels of comfort with prognostic information, clinicians can introduce the topic by simply saying, “I have information about the likely time course of your illness. Would you like to talk about it?”

Chu C et al. Prognostication in palliative care. Clin Med (Lond). 2019 Jul;19(4):306–10. [PMID: 31308109]

Hui D et al. Prognostication in advanced cancer: update and directions for future research. Support Care Cancer. 2019 Jun;27(6):1973–84. [PMID: 30863893]

Smith-Uffen MES et al. Estimating survival in advanced cancer: a comparison of estimates made by oncologists and patients. Support Care Cancer. 2019 Nov 28. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31781946]

Expectations About the End of Life

Expectations About the End of Life

Death is often regarded by clinicians, patients, and families as a failure of medical science. This attitude can create or heighten a sense of guilt about the failure to prevent dying. Both the general public and clinicians often view death as an enemy to be battled furiously in hospitals rather than as an inevitable outcome to be experienced as a part of life at home. As a result, most people in the United States die in hospitals or long-term care facilities even though they may have wished otherwise. There is a trend of fewer deaths in hospitals and more deaths at home or in other community settings.

Relieving suffering, providing support, and helping the patient make the most of their life should be foremost considerations, even when the clinician and patient continue to pursue cure of potentially reversible disease. Patients at the end of life and their families identify a number of elements as important to quality end-of-life care: managing pain and other symptoms adequately, avoiding inappropriate prolongation of dying, communicating clearly, preserving dignity, preparing for death, achieving a sense of control, relieving the burden on others, and strengthening relationships with loved ones.

Communication & Care of the Patient

Communication & Care of the Patient

Caring for patients at the end of life requires the same skills clinicians use in other tasks of medical care: diagnosing treatable conditions, providing patient education, facilitating decision making, and expressing understanding and caring. Communication skills are vitally important and can be improved through training. Higher-quality communication is associated with greater satisfaction and awareness of patient wishes. Clinicians must become proficient at delivering serious news and then dealing with its consequences (Table 5–1). Smartphone and Internet communication resources are available to support clinicians (www.vitaltalk.org), and evidence suggests that communication checklists and guides can be effective. When the clinician and patient do not share a common language, the use of a professional interpreter is needed to facilitate clear communication and help broker cultural issues.

Table 5–1. Suggestions for the delivery of serious news.

Prepare an appropriate place and time.

Address basic information needs.

Be brief and direct; avoid jargon and euphemisms.

Allow for silence and expression of emotions.

Assess and validate patient reactions.

Respond to immediate discomforts and risks.

Listen actively and express empathy.

Achieve a common perception of the problem.

Reassure that care will continue.

Ensure follow-up and make specific plans for the future.

Three further obligations are central to the clinician’s role at this time. First, he or she must work to identify, understand, and relieve physical, psychological, social, and spiritual distress or suffering. Second, clinicians can serve as facilitators or catalysts for hope. While hope for a particular outcome such as cure may fade, it can be refocused on what is still possible. Although a patient may hope for a “miracle,” other more likely hopes can be encouraged and supported, including hope for relief of pain, for reconciliation with loved ones, for discovery of meaning, and for spiritual growth. With such questions as “What is still possible now for you?” and “When you look to the future, what do you hope for?” clinicians can help patients uncover hope, explore meaningful and realistic goals, and develop strategies to achieve them.

Finally, dying patients’ feelings of isolation and fear demand that clinicians assert that they will care for the patient throughout the final stage of life. The promise of nonabandonment is the central principle of end-of-life care and is a clinician’s pledge to serve as a caring partner, a resource for creative problem solving and relief of suffering, a guide during uncertain times, and a witness to the patient’s experiences—no matter what happens. Clinicians can say to a patient, “I will care for you whatever happens.”

Hanning J et al. Goals-of-care discussions for adult patients nearing end of life in emergency departments: a systematic review. Emerg Med Australas. 2019 Aug;31(4):525–32. [PMID: 31044525]

Paladino J et al. Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: a cluster randomized clinical trial of the Serious Illness Care Program. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 1;5(6):801–9. [PMID: 30870556]

Caring for the Family

Caring for the Family

Clinicians must be attuned to the potential impact of illness on the patient’s family: greater physical caregiving responsibilities and financial burdens as well as higher rates of anxiety, depression, chronic illness, and even mortality. The threatened loss of a loved one may create or reveal dysfunctional or painful family dynamics. Family caregivers, typically women, commonly provide the bulk of care for patients at the end of life, yet their work is often not acknowledged, supported, or compensated. Clinicians should recognize that in many cases patients and their families are the unit of care. Simply acknowledging and praising the caregiver can provide much needed and appreciated support.

Clinicians can help families confront the imminent loss of a loved one and often must negotiate amid complex and changing family needs. Identifying a spokesperson for the family, conducting family meetings, allowing all to be heard, and providing time for consensus may help the clinician work effectively with the family. Providing good palliative care to the patient can reduce the risk of depression and complicated grief in loved ones after the patient’s death. Palliative care support directly for caregivers improves caregiver depression.

Durepos P et al. What does death preparedness mean for family caregivers of persons with dementia? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019 May;36(5):436–46. [PMID: 30518228]

Clinician Self-Care

Clinician Self-Care

Many clinicians find caring for patients at the end of life to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practice. However, working with the dying is also sad and can invoke feelings of grief and loss in clinicians. Clinicians must be able to tolerate its uncertainty, ambiguity, and existential challenges. Clinicians also need to recognize and respect their own limitations, attend to their own needs, and work in sustainable health care systems in order to avoid being overburdened, overly distressed, or emotionally depleted.

Kamal AH et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019 Nov 25. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31778784]

Medisauskaite A et al. Reducing burnout and anxiety among doctors: randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Apr;274:383–90. [PMID: 30852432]

Zanatta F et al. Resilience in palliative healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2020 Mar;28(3):971–8. [PMID: 31811483]

Decision Making, Advance Care Planning, & Advance Directives

Decision Making, Advance Care Planning, & Advance Directives

The idea that patients must choose between quality and quantity of life is an outmoded concept that presents patients with a false choice. Clinicians should discuss with patients that an approach that provides concurrent palliative and disease-focused care is the one most likely to achieve improvements in both quality and quantity of life. Patients deserve to have their health care be consistent with their values, preferences, and goals of care. Unfortunately, some evidence suggests that end-of-life care for some patients is determined more by local availability of services and physician comfort than by patient wishes. Well-informed, competent adults have a right to refuse life-sustaining interventions even if this would result in death. In order to promote patient autonomy, clinicians are obligated to inform patients about the risks, benefits, alternatives, and expected outcomes of medical interventions, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, hospitalization and ICU care, and artificial nutrition and hydration. Advance directives are oral or written statements made by patients when they are competent that project their autonomy into the future and are intended to guide care should they lose the ability to make and communicate their own decisions. Advance directives are an important part of advance care planning—defined by an international Delphi panel as “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care. The goal of advance care planning is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences during serious and chronic illness.” Advance directives take effect when the patient can no longer communicate his or her preferences directly. While oral statements about these matters are ethically binding, they are not legally binding in all states. State-specific advance directive forms are available from a number of sources, including http://www.caringinfo.org.

Clinicians should facilitate the process for all patients—ideally, well before the end of life—to consider their preferences, to appoint a surrogate, to talk to that person about their preferences, and to complete a formal advance directive. There are numerous resources that can be helpful, such as https://prepareforyourcare.org. Most patients with a serious illness have already thought about end-of-life issues, want to discuss them with their clinician, want the clinician to bring up the subject, and feel better for having had the discussion. Patients who have such discussions with their clinicians are more satisfied with their clinician, perceived by their family as having a better quality of life at the end of life, less likely to die in the hospital, and more likely to utilize hospice care. The loved ones of patients who engage in advance care planning discussions are less likely to suffer from depression during bereavement. In the United States, Medicare provides payment to clinicians for having advance care planning discussions with patients.

One type of advance directive is the Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care (DPOA-HC) that allows the patient to designate a surrogate decision maker. The DPOA-HC is particularly useful because it is often difficult to anticipate what specific decisions will need to be made. The responsibility of the surrogate is to provide “substituted judgment”—to decide as the patient would, not as the surrogate wants. Clinicians should encourage patients to talk with their surrogates about their preferences generally and about scenarios that are likely to arise, such as the need for mechanical ventilation in a patient with end-stage emphysema. Clear clinician communication is important to correct misunderstandings and address biases. In the absence of a designated surrogate, clinicians usually turn to family members or next of kin. Regulations require health care institutions to inform patients of their rights to formulate an advance directive. Physician (or Medical) Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST or MOLST) or Physician (or Medical) Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST or MOST) forms are clinician orders that document patient preferences and accompany patients wherever they are cared for—home, hospital, or nursing home. They are available in most states and used to complement advance directives for patients approaching the end of life.

Cauley CE et al. DNR, DNI, and DNO? J Palliat Med. 2019 Nov 12. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31718398]

Kim JW et al. Completion rate of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer: a preliminary, cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019 Oct 22;18(1):84. [PMID: 31640677]

O’Halloran P et al. Advance care planning with patients who have end-stage kidney disease: a systematic realist review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 Nov;56(5):795–807. [PMID: 30025939]

Pearse W et al. Advance care planning in the context of clinical deterioration: a systematic review of the literature. Palliat Care. 2019 Jan 19;12:1178224218823509. [PMID: 30718959]

Do Not Attempt Resuscitation Orders

Do Not Attempt Resuscitation Orders

Because the “default” in US hospitals is that patients will undergo CPR in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest, as part of advance care planning, clinicians should elicit patient preferences about CPR. Most patients and many clinicians overestimate the chances of success of CPR. Only about 17% of all patients who undergo CPR in the hospital survive to hospital discharge and, among people with multisystem organ failure, metastatic cancer, and sepsis, the likelihood of survival to hospital discharge following CPR is virtually nil. Patients may ask their hospital clinician to write an order that CPR not be attempted on them. Although this order initially was referred to as a “DNR” (do not resuscitate) order, many clinicians prefer the term “DNAR” (do not attempt resuscitation) to emphasize the low likelihood of success. Some clinicians and institutions use an order to “Allow Natural Death” for situations in which death is imminent and the patient wishes to receive only those interventions that will promote comfort.

For most patients at the end of life, decisions about CPR may not be about whether they will live but about how they will die. Clinicians should correct the misconception that withholding CPR in appropriate circumstances is tantamount to “not doing everything” or “just letting someone die.” While respecting the patient’s right ultimately to make the decision—and keeping in mind their own biases and prejudices—clinicians should offer explicit recommendations about DNAR orders and protect dying patients and their families from feelings of guilt and from the sorrow associated with vain hopes. Clinicians should discuss what interventions will be continued and started to promote quality of life rather than focusing only on what is not to be done. For patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), clinicians must also address issues of turning off these devices, while leaving the pacemaker function on, as death approaches to prevent the uncommon but distressing situation of the ICD discharging during the dying process.

Hospice & Other Palliative Care Services

Hospice & Other Palliative Care Services

In the United States, hospice is a specific type of palliative care service that comprehensively addresses the needs of the dying, focusing on their comfort while not attempting to prolong their life or hasten their death. In the United States, 48.2% of people with Medicare who die use hospice, most at home or in a nursing home where they can be cared for by their family, other caregivers, and visiting hospice staff. Hospice care can also be provided in institutional residences and hospitals. As is true of all types of palliative care, hospice emphasizes individualized attention and human contact, and uses an interdisciplinary team approach. Hospice care can include arranging for respite for family caregivers and assisting with referrals for legal, financial, and other services. Patients in hospice require a physician, preferably their primary care clinician or specialist, to oversee their care.

Hospice care was used by 1.49 million Medicare beneficiaries in 2017 (the most recent year for which there are published data), about 30% of whom had cancer. Hospice is rated highly by families and has been shown to increase patient satisfaction and to decrease family caregiver mortality. In 2017, 48.2% of hospice patients died at home; 31.8% died in a skilled nursing facility. Despite evidence that suggests that hospice care does not shorten length of life, hospice care tends to be used very late, often near the very end of life. In 2017, the mean average length of stay in hospice care in the United States was 76.1 days, but the median length of stay was 24 days. More than half of patients died within 30 days of enrolling in a hospice, and 28% of patients died within 7 days of starting hospice.

In the United States, most hospice organizations require clinicians to estimate the patient’s prognosis to be less than 6 months, since this is a criterion for eligibility under the Medicare hospice benefit that is typically the same for other insurance coverage.

Cultural Issues

Cultural Issues

The individual patient’s experience of dying occurs in the context of a complex interaction of personal, philosophic, and cultural values. Various religious, ethnic, gender, class, and cultural traditions influence a patient’s style of communication, comfort in discussing particular topics, expectations about dying and medical interventions, and attitudes about the appropriate disposition of dead bodies. While there are differences in beliefs regarding advance directives, autopsy, organ donation, hospice care, and withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions among patients of different ethnic groups, clinicians should be careful not to make assumptions about individual patients. Clinicians must appreciate that palliative care is susceptible to the same explicit and implicit biases documented in other medical disciplines. Being sensitive to a person’s cultural beliefs and respecting traditions are important responsibilities of the clinician caring for a patient at the end of life. A clinician may ask a patient, “What do I need to know about you and your beliefs that will help me take care of you?” and “How do you deal with these issues in your family?”

Mathew-Geevarughese SE et al. Cultural, religious, and spiritual issues in palliative care. Prim Care. 2019 Sep;46(3):399–413. [PMID: 31375189]

Wang SY et al. Racial differences in health care transitions and hospice use at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2019 Jun;22(6):619–27. [PMID: 30615546]

Nutrition & Hydration

Nutrition & Hydration

People approaching the end of life often lose their appetite and most stop eating and drinking in their last days. Clinicians should explain to families that the dying patient is not suffering from hunger or thirst; rather, the discontinuation of eating and drinking is part of dying. The anorexia-cachexia syndrome frequently occurs in patients with advanced cancer, and cachexia is common and a poor prognostic sign in patients with heart failure. Seriously ill people often have no hunger despite not eating at all and the associated ketonemia can produce a sense of well-being, analgesia, and mild euphoria. Although it is unclear to what extent withholding hydration at the end of life creates an uncomfortable sensation of thirst, any such sensation is usually relieved by simply moistening the dry mouth. Ice chips, hard candy, swabs, popsicles, or minted mouthwash may be effective. Although this normal process of diminishing oral intake and accompanying weight loss is very common, it can be distressing to patients and families who may associate the offering of food with compassion and love and lack of eating with distressing images of starvation. In response, patients and families often ask about supplemental enteral or parenteral nutrition.

Supplemental artificial nutrition and hydration offer no benefit to those at the end of life and rarely achieve patient and family goals. The American Geriatrics Society recommends against liquid artificial nutrition (“tube feeding”) in people with advanced dementia because it does not provide any benefit. Furthermore, enteral feeding may cause nausea and vomiting in ill patients and can lead to diarrhea in the setting of malabsorption. Artificial nutrition and hydration may increase oral and airway secretions as well as increase the risk of choking, aspiration, and dyspnea; ascites, edema, and effusions may be worsened. In addition, liquid artificial nutrition by nasogastric and gastrostomy tubes and parenteral nutrition impose risks of infection, epistaxis, pneumothorax, electrolyte imbalance, and aspiration—as well as the need to physically restrain the delirious patient to prevent dislodgment of tubes and catheters. A randomized trial of intravenous fluids found no benefit.

Individuals at the end of life have a right to voluntarily refuse all nutrition and hydration. Because they may have deep social and cultural significance for patients, families, and clinicians themselves, decisions about artificial nutrition and hydration are not simply medical. Eliciting perceived goals of artificial nutrition and hydration and correcting misperceptions can help patients and families make clear decisions.

Hoffman MR. Tracheostomies and PEGs: when are they really indicated? Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Oct;99(5):955–65. [PMID: 31446920]

Mayers T et al. International review of national-level guidelines on end-of-life care with focus on the withholding and withdrawing of artificial nutrition and hydration. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019 Sep;19(9):847–53. [PMID: 31389113]

Withdrawal of Curative Efforts

Withdrawal of Curative Efforts

Requests from appropriately informed and competent patients or their surrogates for withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions must be respected. Limitation of life-sustaining interventions prior to death is common practice in ICUs in the United States. The withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions, such as mechanical ventilation, must be approached carefully to avoid patient suffering and distress for those in attendance. Clinicians should educate the patient and family about the expected course of events and the difficulty of determining the precise timing of death after withdrawal of interventions. Sedative and analgesic agents should be administered to ensure patient comfort even at the risk of respiratory depression or hypotension. While “death rattle,” the sound of air flowing over airway secretions, is common in actively dying patients and can be distressing to families, it is doubtful that it causes discomfort to the patient. Turning the patient can decrease the sound of death rattle. There is no evidence that any medications reduce death rattle, and suctioning should be avoided as it can cause patient discomfort.

McPherson K et al. Limitation of life-sustaining care in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med. 2019 May;14(5):303–10. [PMID: 30794145]

Reignier J et al. Withholding and withdrawing life-support in adults in emergency care: joint position paper from the French Intensive Care Society and French Society of Emergency Medicine. Ann Intensive Care. 2019 Sep 23;9(1):105. [PMID: 31549266]

Physician-Assisted Death

Physician-Assisted Death

Physician-assisted death is the legally sanctioned process by which patients who have a terminal illness may request and receive a prescription from a physician for a lethal dose of medication that they themselves would self-administer for the purpose of ending their own life. Terminology for this practice varies. “Physician-assisted death” is used here to clarify that a willing physician provides assistance in accordance with the law (by writing a prescription for a lethal medication) to a patient who makes a request for it and who meets specific criteria. Patients, family members, nonmedical and medical organizations, clinicians, lawmakers, and the public frequently use other terms, such as “physician or medical aid in dying,” “aid in dying,” “death with dignity,” or “physician-assisted suicide.” This latter term is not preferred because when this action is taken according to the law, it is not considered suicide and people who are actively suicidal are not eligible for this process.

Although public and state support for physician-assisted death has grown in the United States, physician-assisted death remains an area of active and intense debate. To date, no state court has recognized physician-assisted death as a fundamental “right.” As of 2019, physician-assisted death has been legalized with careful restriction and specific procedures for residents in nine US states (Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont, Colorado, Hawaii, and California) and in the District of Columbia, making it available to 22% of the US population. Physician-assisted death remains illegal in all other states. Internationally, physician-assisted death (and/or euthanasia, the administration a lethal dose of medication by a clinician) is legal in nine countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Colombia, Canada, Germany, Japan, and the Australian state of Victoria). There are no universal standards about whether patients who request lethal medication for self-administration require a particular prognosis or about what types and levels of suffering qualify them for it, although the current US state laws permitting it generally require physician certification of a terminal disease with a prognosis of 6 months or less. These laws generally also require the individual to be an adult resident of the state, to be physically capable of self-administering the medication, and to be mentally competent (eg, physician or mental health professional certification that they are capable of making and communicating their own healthcare decisions). Laws in the United States authorizing physician-assisted death distinguish it from euthanasia, which is illegal in the United States. Any clinician that participates in physician-assisted death should be familiar with the laws governing its use in their jurisdiction and seek recommendations and help with writing the appropriate prescription.

Most requests for physician-assisted death come from patients with cancer. In the United States, most patients requesting it are male, college-educated, and receiving hospice care. Requests for physician-assisted death are relatively rare. Internationally, less than 5% of deaths are due to either physician-assisted death or euthanasia in locales where one or both of these are legal. In Oregon, the first US state to legalize physician-assisted death, approximately 0.39% of deaths in 2015 resulted from this practice. In California in 2017, just 0.21% of people who died did so through physician-assisted death. Patient motivations for physician-assisted death generally revolve around preserving dignity, self-respect, and autonomy (control), and maintaining personal connections at the end of life rather than experiencing intolerable pain or suffering. Some patients who have requested medication to self-administer for a physician-assisted death later withdraw their request when provided palliative care interventions.

Each clinician must decide his or her personal approach in caring for patients who ask about physician-assisted death. Regardless of the clinician’s personal feelings about the process, the clinician can respond initially by exploring the patient’s reasons and concerns that prompted the request. During the dialog, the clinician should inform the patient about palliative options, including hospice care; access to expert symptom management; and psychological, social, and spiritual support, as needed, and provide reassurance and commitment to address future problems that may arise. For clinicians who object to physician-assisted death on moral or ethical grounds, referral to another clinician may be necessary and may help the patient avoid feeling abandoned. That clinician must be willing to provide the prescription for lethal medication, to care for the patient until death (though it is not necessary to be present at the death), to sign the death certificate listing the underlying terminal condition as the cause of death, and in some jurisdictions to complete a mandatory follow-up form.

Hedberg K et al. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act: 20 years of experience to inform the debate. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Oct 17;167(8):579–83. [PMID: 28975232]

Jansen LA et al. Drawing the line on physician-assisted death. J Med Ethics. 2019 Mar;45(3):190–7. [PMID: 30463933]

McClelland W et al. Withholding or withdrawing life support versus physician-assisted death: a distinction with a difference? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019 Apr;32(2):184–9. [PMID: 30817393]

Russell JA. Physician-hastened-death in patients with progressive neurodegenerative or neuromuscular disorders. Semin Neurol. 2018 Oct;38(5):522–32. [PMID: 30321890]

Ethical & Legal Issues

Ethical & Legal Issues

Clinicians’ care of patients at the end of life is guided by the same ethical and legal principles that inform other types of medical care. Foremost among these are (1) truth-telling, (2) nonmaleficence, (3) beneficence, (4) autonomy, (5) confidentiality, and (6) procedural and distributive justice. Important ethical principles may come into conflict when caring for patients. For example, many treatments that promote beneficence and autonomy, such as surgery or bone marrow transplant, may violate the clinician’s obligation for nonmaleficence; thus, balancing the benefits and risks of treatments is a fundamental ethical responsibility. Similarly, while a patient may express his or her autonomy as a desire for a particular medical intervention such as CPR in the setting of multisystem organ failure, the clinician may decline to provide the intervention because it is futile (ie, of no therapeutic benefit and thus violates both beneficence and nonmaleficence). However, clinicians must use caution in invoking futility, since strict futility is rare and what constitutes futility is often a matter of controversy and subject to bias. While in the vast majority of cases clinicians and patients and families will agree on the appropriateness of and decisions to withdraw life-sustaining interventions, in rare cases, such as CPR in multisystem organ failure, clinicians may determine unilaterally that a particular intervention is medically inappropriate. In such cases, the clinician’s intention to withhold CPR should be communicated to the patient and family and documented, and the clinician must consult with another clinician not involved in the care of the patient. If differences of opinion persist about the appropriateness of particular care decisions, the assistance of an institutional ethics committee should be sought. Because such unilateral actions violate the autonomy of the patient, clinicians should rarely resort to such unilateral actions. Studies confirm that most disagreements between patients and families and clinicians can be resolved with good communication. Although clinicians and family members often feel differently about withholding versus withdrawing life-sustaining interventions, there is consensus among ethicists, supported by legal precedent, of their ethical equivalence.

The ethical principle of “double effect” argues that the potential to hasten imminent death is acceptable if it comes as the known but unintended consequence of a primary intention to provide comfort and relieve suffering. For example, it is acceptable to provide high doses of opioids if needed to control pain even if there is the known and unintended potential effect of depressing respiration.

Chessa F et al. Ethical and legal considerations in end-of-life care. Prim Care. 2019 Sep;46(3):387–98. [PMID: 31375188]

Rodrigues P et al. Palliative sedation for existential suffering: a systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 Jun;55(6):1577–90. [PMID: 29382541]

Psychological, Social, & Spiritual Issues

Psychological, Social, & Spiritual Issues

Dying is not exclusively or even primarily a biomedical event. It is an intimate personal experience with profound psychological, interpersonal, and existential meanings. For many people at the end of life, the prospect of impending death stimulates a deep and urgent assessment of their identity, the quality of their relationships, the meaning and purpose of their life, and their legacy.

A. Psychological Challenges

In 1969, Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross identified five psychological reactions or patterns of emotions that patients at the end of life may experience: denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Most patients will experience these reactions throughout the course of illness and not in an orderly progression. In addition to these five reactions are the perpetual challenges of anxiety and fear of the unknown. Simple information, listening, assurance, and support may help patients with these psychological challenges. Patients and families rank emotional support as one of the most important aspects of good end-of-life care. Psychotherapy and group support may be beneficial as well.

Despite the significant emotional stress of facing death, clinical depression is not normal at the end of life and should be treated. Cognitive and affective signs of depression, such as feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, or helplessness, may help distinguish depression from the low energy and other vegetative signs common with advanced illness. Although traditional antidepressant treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective, more rapidly acting medications, such as dextroamphetamine (2.5–7.5 mg orally at 8 am and noon) or methylphenidate (2.5–10 mg orally at 8 am and noon), may be particularly useful when the end of life is near or while waiting for another antidepressant medication to take effect. Ketamine is now approved, with restrictions, as a treatment for depression and psychedelics are being explored as rapid-onset treatment for anxiety and depression at the end of life. Some research suggests a mortality benefit from treating depression in the setting of serious illness.

B. Social Challenges

At the end of life, patients should be encouraged to take care of personal, professional, and business obligations. These tasks include completing important work or personal projects, distributing possessions, writing a will, and making funeral and burial arrangements. The prospect of death often prompts patients to examine the quality of their interpersonal relationships and to begin the process of saying goodbye (Table 5–2). Concern about estranged relationships or “unfinished business” with significant others and interest in reconciliation may become paramount at this time.

Table 5–2. Five statements often necessary for the completion of important interpersonal relationships.

C. Spiritual Challenges

Spirituality includes the attempt to understand or accept the underlying meaning of life, one’s relationships to oneself and other people, one’s place in the universe, one’s legacy, and the possibility of a “higher power” in the universe. People may experience spirituality as part of or distinct from particular religious practices or beliefs.

Unlike physical ailments, such as infections and fractures, which usually require a clinician’s intervention to be treated, the patient’s spiritual concerns often require only a clinician’s attention, listening, and witness. Clinicians can inquire about the patient’s spiritual concerns and ask whether the patient wishes to discuss them. For example, asking, “How are you within yourself?” or “Are you at peace?” communicates that the clinician is interested in the patient’s whole experience and provides an opportunity for the patient to share perceptions about his or her inner life. Questions that might constitute an existential “review of systems” are presented in Table 5–3. Formal legacy work and dignity therapy have been shown to be effective in improving quality of life and spiritual well-being.

Table 5–3. An existential review of systems.

Intrapersonal

“What does your illness/dying mean to you?”

“What do you think caused your illness?”

“How have you been healed in the past?”

“What do you think is needed for you to be healed now?”

“What is right with you now?”

“What do you hope for?”

“Are you at peace?”

Interpersonal

“Who is important to you?”

“To whom does your illness/dying matter?”

“Do you have any unfinished business with significant others?”

Transpersonal

“What is your source of strength, help, or hope?”

“Do you have spiritual concerns or a spiritual practice?”

“If so, how does your spirituality relate to your illness/dying, and how can I help integrate your spirituality into your health care?”

“What do you think happens after we die?”

“What do you think is trying to happen here?”

Attending to the spiritual concerns of patients calls for listening to their stories. Storytelling gives patients the opportunity to verbalize what is meaningful to them and to leave something of themselves behind—a legacy, the promise of being remembered. Storytelling may be facilitated by suggesting that the patient share his or her life story with family members, make an audio or video recording, assemble a photo album, organize a scrapbook, or write or dictate an autobiography.

The end of life offers an opportunity for psychological, interpersonal, and spiritual development and to experience and achieve important goals. Individuals may grow—even experience a heightened sense of well-being or transcendence—in the process of dying. Through listening, support, and presence, clinicians may help foster this learning and be a catalyst for this transformation. Rather than thinking of dying simply as the termination of life, clinicians and patients may be guided by a developmental model of life that recognizes a series of lifelong developmental tasks and landmarks and allows for growth at the end of life.

Egan R et al. Spiritual beliefs, practices, and needs at the end of life: results from a New Zealand national hospice study. Palliat Support Care. 2017 Feb;31(2):140–6. [PMID: 27572901]

Gerson SM et al. Medical aid in dying, hastened death and suicide: a qualitative study of hospice professionals’ experiences from Washington State. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Mar;59(3):679–86. [PMID: 31678464]

Puchalski CM et al. Spiritual considerations. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;32(3):505–17. [PMID: 29729785]

Strada EA. Psychosocial issues and bereavement. Prim Care. 2019 Sep;46(3):373–86. [PMID: 31375187]

Wholihan D. Psychological issues of patient transition from intensive care to palliative care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;31(4):547–56. [PMID: 31685121]

TASKS AFTER DEATH

After the death of a patient, the clinician is called upon to perform a number of tasks, both required and recommended. The clinician must plainly and directly inform the family of the death, complete a death certificate, contact an organ procurement organization, and request an autopsy. Providing words of sympathy and reassurance, time for questions and initial grief and, for people who die in the hospital or other health care facility, a quiet private room for the family to grieve is appropriate and much appreciated.

The Pronouncement & Death Certificate

The Pronouncement & Death Certificate

In the United States, state policies direct clinicians to confirm the death of a patient in a formal process called “pronouncement.” The diagnosis of death is typically easy to make, and the clinician need only verify the absence of spontaneous respirations and cardiac activity by auscultating for each for 1 minute. A note describing these findings, the time of death, and that the family has been notified is entered in the patient’s medical record. In many states, when a patient whose death is expected dies outside of the hospital (at home or in prison, for example), nurses may be authorized to report the death over the telephone to a physician who assumes responsibility for signing the death certificate within 24 hours. For traumatic deaths, some states allow emergency medical technicians to pronounce a patient dead at the scene based on clearly defined criteria and with physician telephonic or radio supervision.

While the pronouncement may often seem like an awkward and unnecessary formality, clinicians may use this time to reassure the patient’s loved ones at the bedside that the patient died peacefully and that all appropriate care had been given. Both clinicians and families may use the ritual of the pronouncement as an opportunity to begin to process emotionally the death of the patient.

Physicians are legally required to report certain deaths to the coroner and to accurately report the underlying cause of death on the death certificate. This reporting is important both for patients’ families (for insurance purposes and the need for an accurate family medical history) and for the epidemiologic study of disease and public health. The physician should be specific about the major cause of death being the condition without which the patient would not have died (eg, “decompensated cirrhosis”) and its contributory cause (eg, “hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections, chronic alcoholic hepatitis, and alcoholism”) as well as any associated conditions (eg, “acute kidney injury”)—and not simply put down “cardiac arrest” as the cause of death. In relevant cases, it is prohibited (in some jurisdictions) to list either “physician-assisted death” (or any synonymous term) or the medication used to accomplish it (eg, secobarbital) on the death certificate; instead, the clinician prescribing the lethal dose of medication for this purpose and following the patient until death must (in most jurisdictions) complete and submit a follow-up form and list the cause of death as the underlying condition that led to death.

Hatano Y et al. Physician behavior toward death pronouncement in palliative care units. J Palliat Med. 2018 Mar;21(3):368–72. [PMID: 28945507]

Autopsy & Organ Donation

Autopsy & Organ Donation

Discussing the options and obtaining consent for autopsy and organ donation with patients prior to death is a good practice as it advances the principle of patient autonomy and lessens the responsibilities of distressed family members during the period immediately following the death. In the United States, federal regulations require that a designated representative of an organ procurement organization approach the family about organ donation if the organs are appropriate for transplantation because designated organ transplant personnel are more experienced and successful than treating clinicians at obtaining consent for organ donation from surviving family members. While most people in the United States support the donation of organs for transplants, organ transplantation is severely limited by the availability of donor organs. The families of donors experience a sense of reward in contributing, even through death, to the lives of others.

The results of an autopsy may help surviving family members and clinicians understand the exact cause of a patient’s death and foster a sense of closure. Despite the use of more sophisticated diagnostic tests, the rate of unexpected findings at autopsy has remained stable, and thus, an autopsy can provide important health information to families. Pathologists can perform autopsies without interfering with funeral plans or the appearance of the deceased. A clinician–family conference to review the results of the autopsy provides a good opportunity for clinicians to assess how well families are grieving and to answer questions.

Buja LM et al. The importance of the autopsy in medicine: perspectives of pathology colleagues. Acad Pathol. 2019 Mar 10;6:2374289519834041. [PMID: 30886893]

Follow-Up & Grieving

Follow-Up & Grieving

Proper care of patients at the end of life includes following up with surviving family members after the patient has died. Contacting loved ones by telephone enables the clinician to assuage any guilt about decisions the family may have made, assess how families are grieving, reassure them about the nature of normal grieving, and identify complicated grief or depression. Clinicians can recommend support groups and counseling as needed. A card or telephone call from the clinician to the family days to weeks after the patient’s death (and perhaps on the anniversary of the death) allows the clinician to express concern for the family and the deceased.

After a patient dies, clinicians also grieve. Although clinicians may be relatively unaffected by the deaths of some patients, other deaths may cause feelings of sadness, loss, and guilt. These emotions should be recognized as the first step toward processing and healing them. Each clinician may find personal or communal resources that help with the process of grieving. Shedding tears, sharing with colleagues, taking time for reflection, and engaging in traditional or personal mourning rituals all may be effective. Attending the funeral of a patient who has died can be a satisfying personal experience that is almost universally appreciated by families and that may be the final element in caring well for people at the end of life.

Johannsen M et al. Psychological interventions for grief in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 15;253:69–86. [PMID: 31029856]

Strada EA. Psychosocial issues and bereavement. Prim Care. 2019 Sep;46(3):373–86. [PMID: 31375187]

PAIN MANAGEMENT

TAXONOMY OF PAIN

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. Acute pain resolves within the expected period of healing and is self-limited. Chronic pain persists beyond the expected period of healing and is itself a disease state. In general, chronic pain is defined as extending beyond 3–6 months, although definitions vary in terms of the time period from initial onset of nociception. Cancer pain is in its own special category because of the unique ways neoplasia and its therapies (such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy) can lead to burdensome pain. Finally, related to cancer pain, there is pain at the end of life, for which measures to alleviate suffering may take priority over promoting restoration of function.

Pain is a worldwide burden; across the globe; one in five adults suffers from pain. In 2010, members from 130 countries signed the Declaration of Montreal stating that access to pain management is a fundamental human right. The first CDC guidelines on opioid prescribing for chronic pain, including chronic noncancer pain, cancer pain, and pain at the end of life, were published in March of 2016, and continue to be updated.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. 2019 Aug 28. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

Dowell D et al. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2285–7. [PMID: 31018066]

ACUTE PAIN

Acute pain resolves within the expected period of healing and is self-limited. Common examples include pain from dental caries, kidney stones, surgery, or trauma. Management of acute pain depends on comprehending the type of pain (somatic, visceral, or neuropathic) and on understanding the risks and benefits of potential therapies. At times, treating the underlying cause of the pain (eg, dental caries) may be all that is needed, and pharmacologic therapies may not be required for additional analgesia. On the other hand, not relieving acute pain can have consequences beyond the immediate suffering. Inadequately treated acute pain can develop into chronic pain in some patients. This transition from acute to chronic pain (so-called “chronification” of pain) depends on the pain’s cause, type, and severity and on the patient’s age, psychological status, and genetics, among other factors. This transition is an area of increasing study because chronic pain leads to significant societal costs beyond the individual’s experiences of suffering, helplessness, and depression. Emerging studies have shown that increased intensity and duration of acute pain may be correlated with a higher incidence of chronic pain, and regional anesthesia, ketamine, gabapentinoids, and cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors may be helpful for prevention of chronic postsurgical pain. These approaches are particularly important given concerns that exposure to opioids in the perioperative period can lead to chronic opioid dependence beyond the immediate postoperative period.

The Oxford League Table of Analgesics is a useful guide; for example, it lists the number-needed-to-treat for specific doses of various medications to relieve acute pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or COX inhibitors are at the top of the list, with the lowest number-needed-to-treat. These medications can be delivered via oral, intramuscular, intravenous, intranasal, rectal, and other routes of administration. They generally work by inhibiting COX-1 and -2 and therefore reduce the levels of prostaglandins involved in inflammatory nociception (eg, PGI2 and PGE2). These oxygenase enzymes also determine levels of other breakdown products such as other prostaglandins, thromboxane, and prostacyclins that play a role in renal, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular homeostasis. For this reason, the primary limitation of the COX inhibitors is their side effect profile of gastritis, kidney dysfunction, bleeding, hypertension, and cardiovascular adverse events such as myocardial infarction or stroke. Ketorolac is primarily a COX-1 inhibitor that has an analgesic effect as potent as morphine at the appropriate dosage. Like most pharmacologic therapies, the limitation of COX inhibitors is that they have a “ceiling” effect, meaning that beyond a certain dose, there is no additional benefit.

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is effective as a sole agent, or in combination with a COX inhibitor or an opioid in acute pain. Its mechanism of action remains undetermined but is thought to act centrally through mechanisms such as the prostaglandin, serotonergic, and opioid pathways. It is one of the most widely used and best tolerated analgesics; its primary limitation is hepatoxicity when given in high doses or to patients with underlying impaired liver function.

Postoperatively, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with intravenous morphine, hydromorphone, or another opioid can achieve analgesia faster and with less daily medication requirement than with standard “as needed” or even scheduled intermittent dosing. PCA has been adapted for use with oral analgesic opioid medications and for neuraxial delivery of both opioids and local anesthetics in the epidural and intrathecal spaces. The goal of PCA is to maintain a patient’s plasma concentration of opioid in the “therapeutic window,” between the minimum effective analgesic concentration and a toxic dose.

In order to prevent opioid use disorder and prolonged inappropriate opioid use, multimodal analgesia (including regional anesthesia) has been employed to decrease the need for postoperative opioids. Patients may undergo either neuraxial anesthesia with an epidural catheter, for example, or undergo regional anesthesia with a nerve block with or without a catheter. These techniques are effective for both intraoperative pain and postoperative pain management and can diminish the need for both intraoperative and postoperative opioids.

Helander EM et al. Multimodal analgesia, current concepts, and acute pain considerations. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017 Jan;21(1):3. [PMID: 28132136]

Polomano RC et al. Multimodal analgesia for acute postoperative and trauma-related pain. Am J Nurs. 2017 Mar;117(3 Suppl 1):S12–26. [PMID: 28212146]

Small C et al. Acute postoperative pain management. Br J Surg. 2020 Jan;107(2):e70–80. [PMID: 31903595]

CHRONIC NONCANCER PAIN

Chronic noncancer pain may begin as acute pain that then fails to resolve and extends beyond the expected period of healing or it may be a primary disease state, rather than the symptom residual from another condition. Common examples of chronic noncancer pain include chronic low-back pain and arthralgias (often somatic in origin), chronic abdominal pain and pelvic pain (often visceral in origin), and chronic headaches, peripheral neuropathy, and postherpetic neuralgia (neuropathic origin) as well as other less common but debilitating syndromes such as chronic trigeminal neuralgia (neuropathic origin) and complex regional pain syndrome (mixed origin). Chronic noncancer pain is common, with the World Health Organization estimating a worldwide prevalence of 20%. In the United States, 11% of adults suffer from chronic noncancer pain, and the Institute of Medicine estimates that it costs $635 billion annually in treatment and lost productivity costs.

Chronic noncancer pain requires interdisciplinary management. Generally, no one therapy by itself is sufficient to manage such chronic pain. Physical or functional therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have been shown to be the most effective for treating chronic noncancer pain, but other modalities including pharmacologic therapy, interventional modalities, and complementary/integrative approaches are useful in caring for affected patients.

Chronic low-back pain is one example of a common chronic noncancer pain. It causes more disability globally than any other condition. Chronic low-back pain includes spondylosis, spondylolisthesis, and spinal canal stenosis (Chapter 24), and the “failed back surgery syndrome,” a term used to refer to patients in whom chronic pain develops, persists after lumbar spine surgery, or both. Also referred to as the post-laminectomy pain syndrome, it can affect 10–40% of patients after lumbar spine surgery.

The importance of clinicians knowing the many causes of chronic low-back pain and, in particular, understanding how anatomic structures relate to one another and how they can cause the different types of low-back pain, has been highlighted by the epidemic of opioid abuse in the United States since the year 2000. In fact, evidence-based practice does not support the use of prolonged opioid therapy for chronic low-back pain.

Manchikanti L et al. Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2017 Feb;20(2S):S3–92. [PMID: 28226332]

Qaseem A et al. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Apr 4;166(7):514–30. [PMID: 28192789]

CANCER PAIN

Cancer pain deserves its own category because it is unique in cause and in therapies. Cancer pain consists of both acute pain and chronic pain from the neoplasm itself and from the therapies associated with it, such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy. In addition, patients with cancer pain may also have acute or chronic non–cancer-related pain, and this possibility should not be overlooked when taking care of cancer patients.

Cancer pain includes somatic pain (eg, neoplastic invasion of tissue such as painful fungating chest wall masses in breast cancer), visceral pain (eg, painful hepatomegaly from liver metastases, stretching the liver capsule), neuropathic pain (eg, neoplastic invasion of sacral nerve roots), or pain from a paraneoplastic syndrome (eg, peripheral neuropathy related to anti-Hu antibody production). Chemotherapy can cause peripheral neuropathies, radiation can cause neuritis or skin allodynia, and surgery can cause persistent postsurgical pain syndromes such as post-mastectomy or post-thoracotomy pain syndromes.

Generally, patients with cancer pain do not exhibit a single type of pain—they may have multiple reasons for pain and thus benefit from a comprehensive and multimodal strategy. The WHO Analgesic Ladder, first published in 1986, suggests starting medication treatment with nonopioid analgesics, then weak opioid agonists, followed by strong opioid agonists. While opioid therapy can be helpful for a majority of patients living with cancer pain, therapy must be individualized depending on the individual patient, their family, and the clinician. For example, if one of the goals of care is to have a lucid and coherent patient, opioids may not be the optimal choice; interventional therapies such as implantable devices may be an option, weighing their risks and costs against their potential benefits. Alternatively, in dying patients, provided there is careful documentation of continued, renewed, or accelerating pain, use of opioid doses exceeding those recommended as standard for acute (postoperative) pain is acceptable.

One of the unique challenges in treating cancer pain is that it is often a “moving target,” with disease progression and improvements in disease progression or worsening pain directly stemming from chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy. Therefore, frequent adjustments may be required to any pharmacologic regimen. Interventional approaches such as celiac plexus neurolysis and intrathecal therapy are well-studied and may be appropriate both for analgesia as well as reduction of side effects from systemic medications. Radiation therapy (including single-fraction external beam treatments) or radionuclide therapy (eg, strontium-89), which aims to decrease the size of both primary and metastatic disease, is one of the unique options for patients with pain from cancer.

Careskey H et al. Interventional anesthetic methods for pain in hematology/oncology patients. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;32(3):433–45. [PMID: 29729779]

Lau J et al. Interventional anesthesia and palliative care collaboration to manage cancer pain: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. 2020 Feb;67(2):235–46. [PMID: 31571119]

Neufeld NJ et al. Cancer pain: a review of epidemiology, clinical quality and value impact. Future Oncol. 2017 Apr;13(9):833–41. [PMID: 27875910]

Paice JA. Under pressure: the tension between access and abuse of opioids in cancer pain management. J Oncol Pract. 2017 Sep;13(9):595–6. [PMID: 28813190]

PAIN AT THE END OF LIFE

Pain is what many people say they fear most about dying, and pain at the end of life is consistently undertreated. Up to 75% of patients dying of cancer, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AIDS, or other diseases experience pain. In the United States, the Joint Commission includes pain management standards in its reviews of health care organizations and, in 2018, it began mandating that each hospital have a designated leader in pain management.

The ratio of risk versus benefit changes in end-of-life pain management. Harms from the use of opioid analgesics, including death, eg, from respiratory depression (rare), are perhaps less of a concern in patients approaching the end of life. In all cases, clinicians must be prepared to use appropriate doses of opioids in order to relieve this distressing symptom for these patients. Typically, for ongoing cancer pain, a long-acting opioid analgesic can be given around the clock with a short-acting opioid medication as needed for “breakthrough” pain.

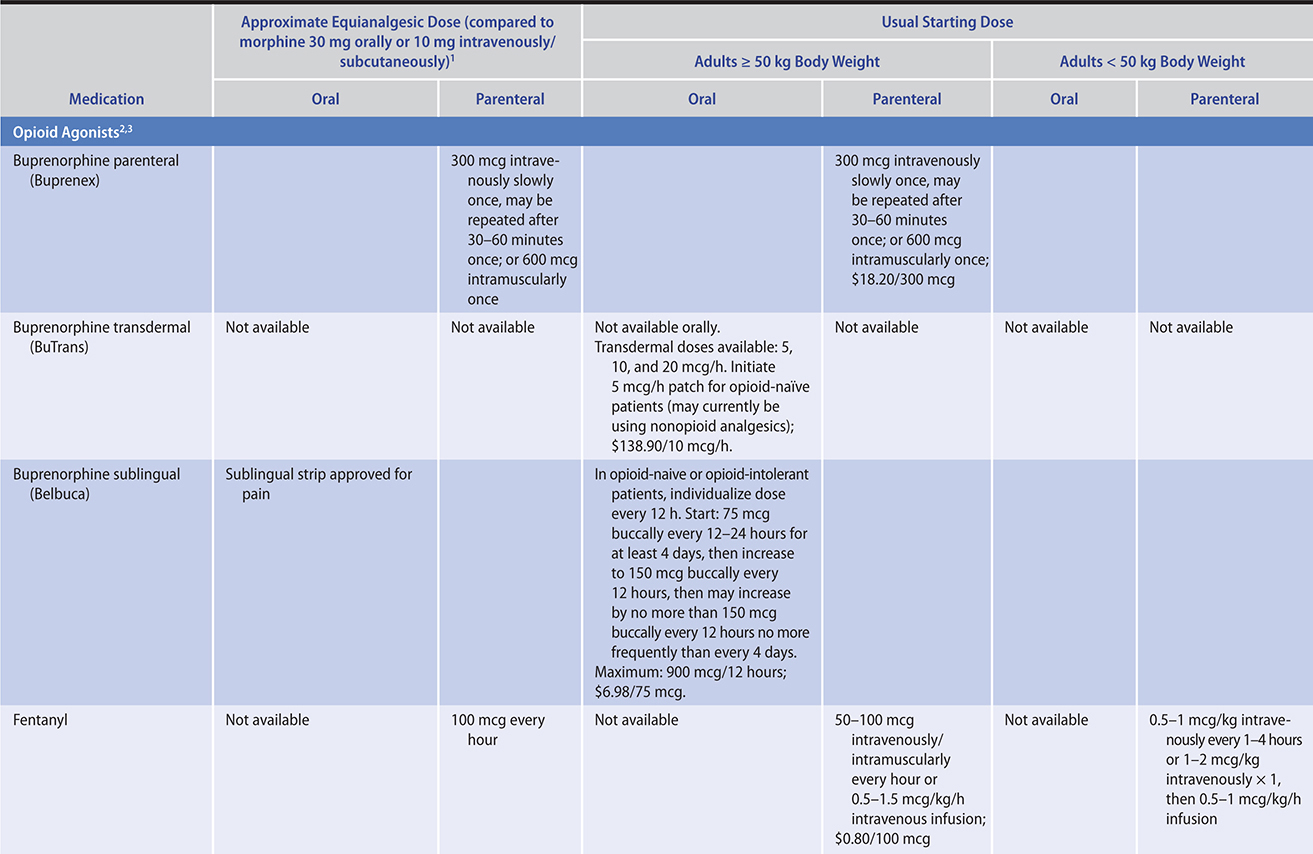

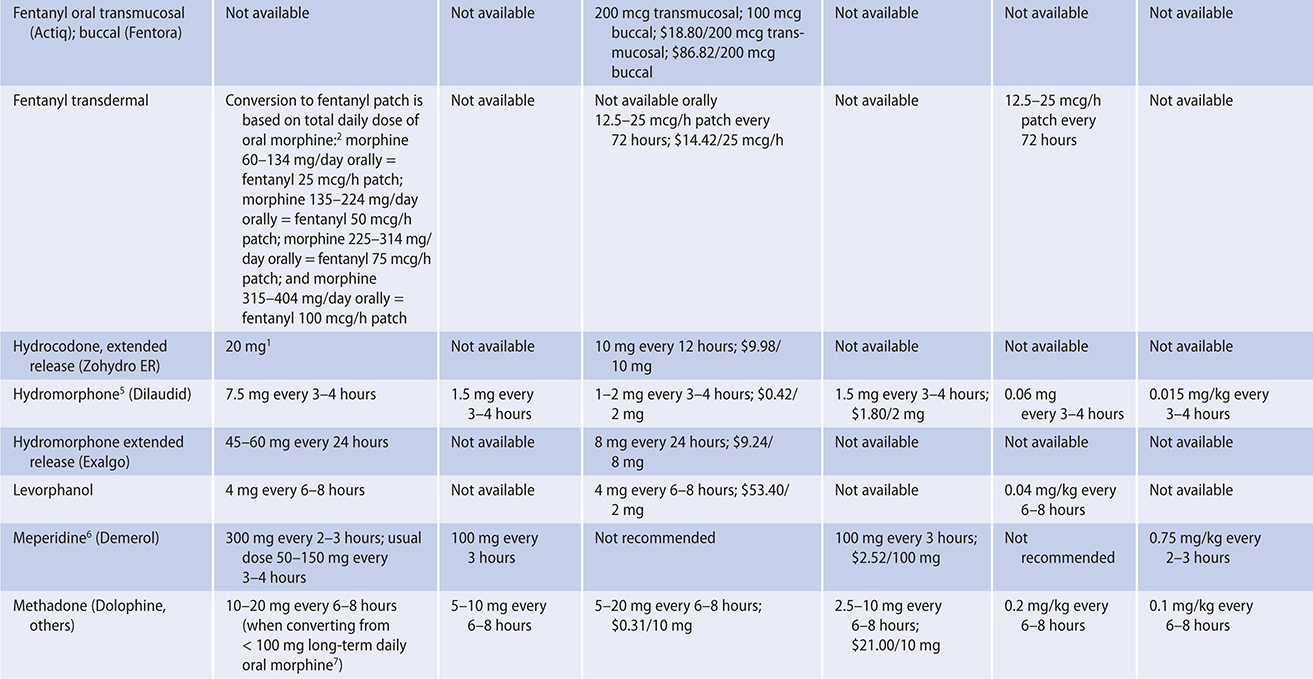

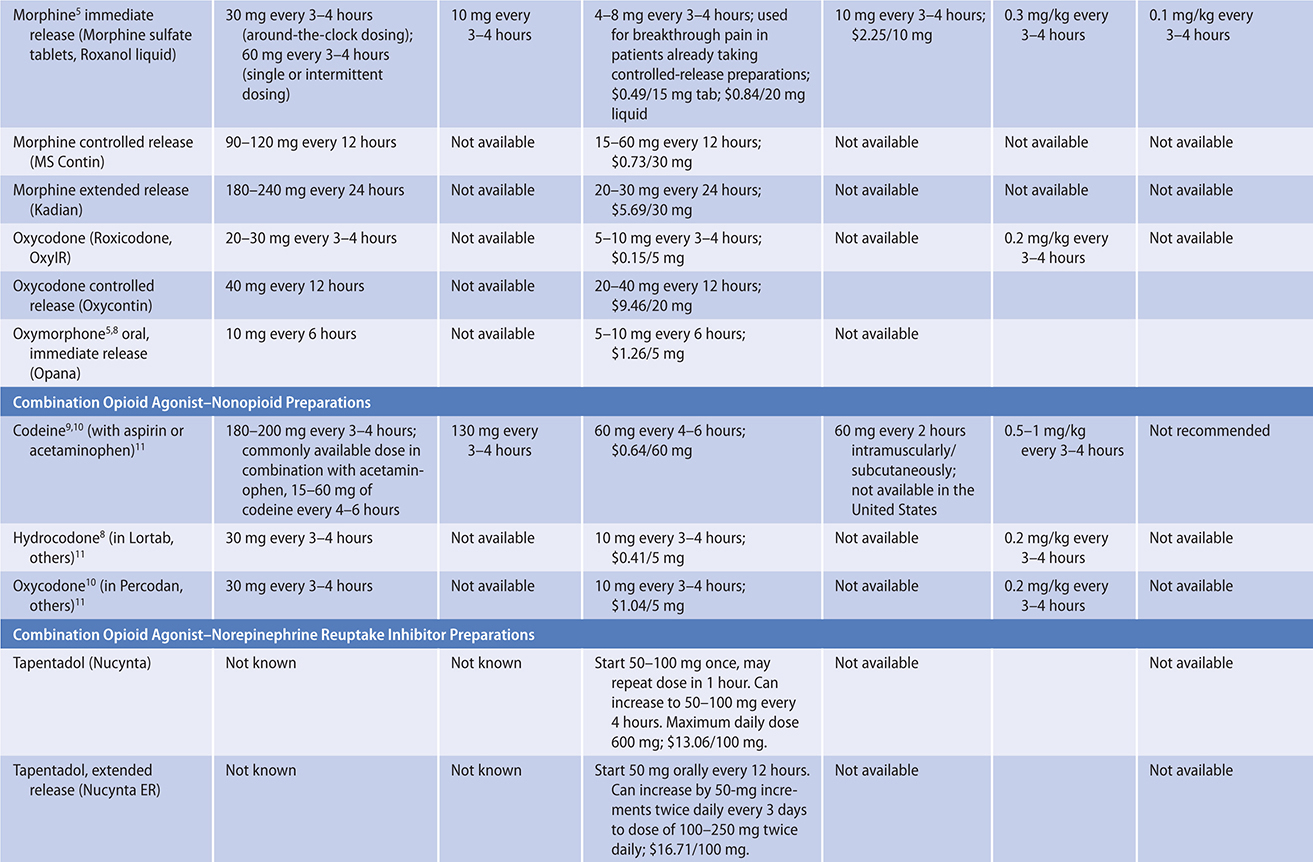

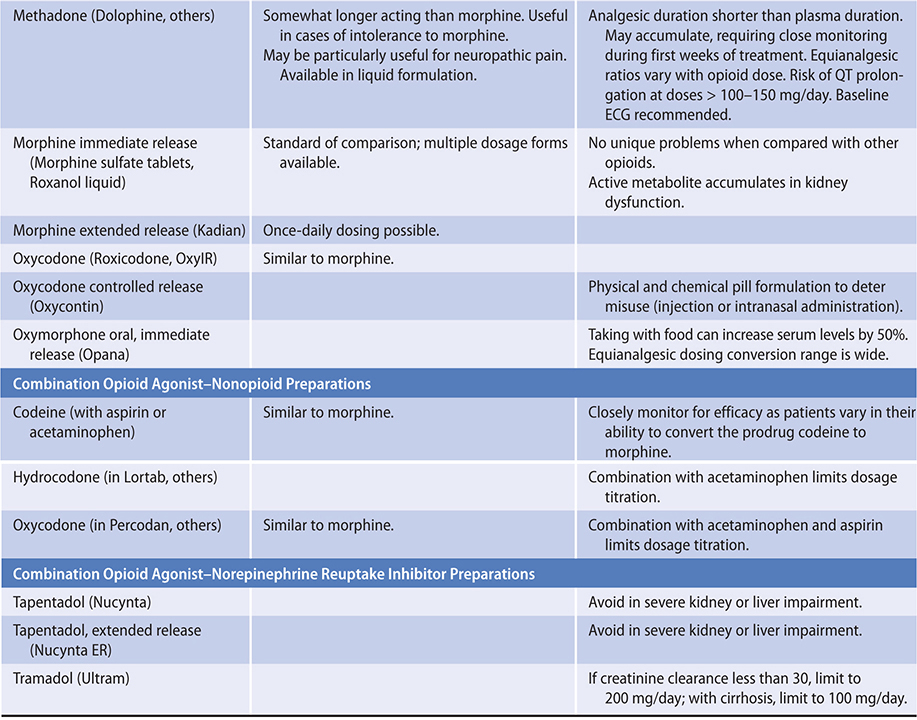

PRINCIPLES OF PAIN MANAGEMENT

The experience of pain is unique to each person and influenced by many factors, including the patient’s prior experiences with pain, meaning given to the pain, emotional stresses, and family and cultural influences. Pain is a subjective and multi-faceted phenomenon, and clinicians cannot reliably detect its existence or quantify its severity without asking the patient directly. A brief means of assessing pain and evaluating the effectiveness of analgesia is to ask the patient to rate the degree of pain along a numeric or visual pain scale (Table 5–4), assessing trends over time. Clinicians should ask about the nature, severity, timing, location, quality, and aggravating and relieving factors of the pain.

Table 5–4. Pain assessment scales.

General guidelines for diagnosis and management of pain are recommended for the treatment of all patients with pain but clinicians must comprehend that such guidelines may not be suited for every individual. Because of pain’s complexity, it is important to understand benefits and risks of treatment with growing evidence for each patient. Distinguishing between nociceptive (somatic or visceral) and neuropathic pain is essential to proper management.

In addition, while clinicians should seek to diagnose the underlying cause of pain and then treat it, they must balance the burden of diagnostic tests or therapeutic interventions with the patient’s suffering. For example, single-fraction radiation therapy for painful bone metastases or nerve blocks for neuropathic pain may obviate the need for ongoing treatment with analgesics and their side effects. Regardless of decisions about seeking and treating the underlying cause of pain, every patient should be offered prompt pain relief.

The aim of effective pain management is to meet specific goals, such as preservation or restoration of function or quality of life, and this aim must be discussed between provider and patient, as well as their family. For example, some patients may wish to be completely free of pain even at the cost of significant sedation, while others will wish to control pain to a level that still allows maximal cognitive functioning.

Whenever possible, the oral route of analgesic administration is preferred because it is easier to manage at home, is not itself painful, and imposes no risk from needle exposure. In unique situations, or near the end of life, transdermal, subcutaneous, rectal, and intravenous routes of administration are used; intrathecal administration is used when necessary.

Finally, pain management should not automatically indicate opioid therapy. While many individuals fare better with opioid therapy in specific situations, this does not mean that opioids are the answer for every patient. There are situations where opioids actually make the quality of life worse for individuals, due to a lack of adequate analgesic effect or due to their side effects.

Barriers to Good Care

Barriers to Good Care

One barrier to good pain control is that many clinicians have limited training and clinical experience with pain management and thus are reluctant to attempt to manage severe pain. Lack of knowledge about the proper selection and dosing of analgesic medications carries with it attendant and typically exaggerated fears about the side effects of pain medications. Consultation with a palliative care or a pain management specialist may provide additional expertise.