18

Gynecologic Disorders

Jason Woo, MD, MPH, FACOG

Jill Long, MD, MPH, MHS, FACOG1

PREMENOPAUSAL ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Accurate diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) depends on appropriate categorization and diagnostic tests.

Accurate diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) depends on appropriate categorization and diagnostic tests.

Pregnancy should always be ruled out as a cause of AUB in reproductive age women.

Pregnancy should always be ruled out as a cause of AUB in reproductive age women.

The evaluation of AUB depends on the age and risk factors of the patient.

The evaluation of AUB depends on the age and risk factors of the patient.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Normal menstrual bleeding lasts an average of 5 days (range, 2–7 days), with a mean blood loss of 40 mL per cycle. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) refers to menstrual bleeding of abnormal quantity, duration, or schedule. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) introduced the current classification system for abnormal uterine bleeding in 2011, which was then endorsed by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. This classification system pairs AUB with descriptive terms denoting the bleeding pattern (ie, heavy, light and menstrual, intermenstrual) and etiology (the acronym PALM-COEIN standing for Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy and hyperplasia, Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, and Not yet classified). In adolescents, AUB often occurs as a result of persistent anovulation due to the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and represents normal physiology. Once regular menses has been established during adolescence, ovulatory dysfunction AUB (AUB-O) accounts for most cases. AUB in women aged 19–39 years is often a result of pregnancy, structural lesions, anovulatory cycles, use of hormonal contraception, or endometrial hyperplasia.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

The diagnosis depends on the following: (1) confirming uterine source of the bleeding; (2) excluding pregnancy and confirming patient is premenopausal; (3) ascertaining whether the bleeding pattern suggests regular ovulatory bleeding or anovulatory bleeding; (4) determining contribution of structural abnormalities (PALM), including risk for malignancy/hyperplasia; (5) identifying risk of medical conditions that may impact bleeding (eg, inherited bleeding disorders, endocrine disease, risk of infection); and (6) assessing contribution of current medications, including contraceptives or natural product supplements or combinations that may affect bleeding.

B. Laboratory Studies

A complete blood count, pregnancy test, and thyroid tests should be done. For adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding and adults with a positive screening history, coagulation studies should be considered, since up to 18% of women with severe menorrhagia have an underlying coagulopathy. Vaginal or urine samples should be obtained for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture to rule out infectious causes. If indicated, cervical cytology should also be obtained.

C. Imaging

Transvaginal ultrasound is useful to assess for presence of fibroids, suspicion of adenomyosis, and to evaluate endometrial thickness. Sonohysterography or hysteroscopy may be used to diagnose endometrial polyps or subserous myomas. MRI is not a primary imaging modality for AUB but can more definitively diagnose submucous myomas and adenomyosis.

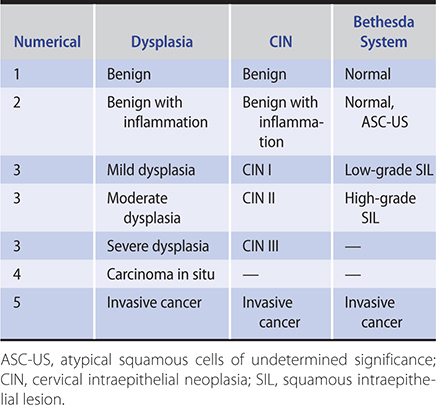

D. Cervical Biopsy and Endometrial Sampling

The purpose of endometrial sampling is to determine if hyperplasia or carcinoma is present. Sampling methods and other gynecologic diagnostic procedures are described in Table 18–1. Polyps, endometrial hyperplasia and, occasionally, submucous myomas are identified on endometrial biopsy. Endometrial sampling should be performed in patients with AUB who are 45 years and older, or in younger patients with a history of unopposed estrogen exposure or failed medical management and persistent AUB. If the Papanicolaou smear abnormality requires it or a gross cervical lesion is seen, colposcopic-directed biopsies and endocervical curettage are usually indicated.

Table 18–1. Common gynecologic diagnostic procedures.

Colposcopy

Visualization of cervical, vaginal, or vulvar epithelium under 5–50 × magnification with and without dilute acetic acid to identify abnormal areas requiring biopsy. An office procedure.

Dilation & curettage (D&C)

Dilation of the cervix and curettage of the entire endometrial cavity, using a metal curette or suction cannula and often using forceps for the removal of endometrial polyps. Can usually be done in the office under local anesthesia or in the operating room under sedation or general anesthesia. D&C is often combined with hysteroscopy for improved sensitivity.

Endometrial biopsy

Blind sampling of the endometrium by means of a curette or small aspiration device without cervical dilation. Diagnostic accuracy similar to D&C. An office procedure performed with or without local anesthesia.

Endocervical curettage

Removal of endocervical epithelium with a small curette for diagnosis of cervical dysplasia and cancer. An office procedure performed with or without local anesthesia.

Hysterosalpingography

Injection of radiopaque dye through the cervix to visualize the uterine cavity and oviducts. Mainly used in investigation of infertility, to identify a space-occupying lesion, or to confirm fallopian tube inserts (Essure®) sterilization.

Hysteroscopy

Visual examination of the uterine cavity with a small fiberoptic endoscope passed through the cervix. Curettage, endometrial ablation, biopsies of lesions, and excision of myomas or polyps can be performed concurrently. Can be done in the office under local anesthesia or in the operating room under sedation or general anesthesia. Greater sensitivity for diagnosis of uterine pathology than D&C.

Laparoscopy

Visualization of the abdominal and pelvic cavity through a small fiberoptic endoscope passed through a subumbilical incision. Permits diagnosis, tubal sterilization, and treatment of many conditions previously requiring laparotomy. General anesthesia is used.

Saline infusion sonohysterography

Introduction of saline solution into endometrial cavity with a catheter to visualize submucous myomas or endometrial polyps by transvaginal ultrasound. May be performed in the office with oral or local analgesia, or both.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment for premenopausal patients with AUB depends on the etiology of the bleeding, determined by history, physical examination, laboratory findings, imaging, and endometrial sampling. Patients with AUB due to submucosal myomas, infection, gestational trophoblastic conditions, thrombophilia, or pelvic neoplasms may require definitive therapy. A large proportion of premenopausal patients, however, have ovulatory dysfunction AUB (AUB-O).

Treatment for AUB-O should include consideration of potentially contributing medical conditions. Subsequently, AUB-O can be treated hormonally. For women amenable to using contraceptives, estrogen-progestin contraceptives or the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD) are both effective treatments. The choice between the two depends on whether any contraindications to these treatments exist as well as patient preference. High-dose oral or injectable progestin-only medications are also generally effective. For patients with irregular or light bleeding, medroxyprogesterone acetate, 10 mg/day orally, or norethindrone acetate, 5 mg/day orally, should be given for 10 days, following which withdrawal bleeding will occur. If successful, the treatment can be repeated for several cycles, starting medication on day 15 of subsequent cycles, or it can be reinstituted if amenorrhea or dysfunctional bleeding recurs. Nonhormonal options include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen or mefenamic acid, in the usual anti-inflammatory doses taken during menses, and tranexamic acid 1300 mg three times per day orally for up to 5 days. Both have been shown to decrease menstrual blood loss by about 40%, with tranexamic acid superior to NSAIDs in direct comparative studies.

Women who are experiencing heavier bleeding can be given a taper of any of the combination oral contraceptives (with 30–35 mcg of estrogen estradiol) to control the bleeding. There are several commonly used contraceptive dosing regimens, including four times daily for 1 or 2 days followed by two pills daily through day 5 and then one pill daily through day 20; after withdrawal bleeding occurs, pills are taken in the usual dosage for three cycles. In cases of intractable heavy bleeding, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist such as depot leuprolide, 3.75 mg intramuscularly monthly, can be used for up to 6 months to create a temporary cessation of menstruation by ovarian suppression. These therapies require 2–4 weeks to down-regulate the pituitary and stop bleeding and will not stop bleeding acutely. In cases of heavy bleeding requiring hospitalization, intravenous conjugated estrogens, 25 mg every 4 hours for three or four doses, can be used, followed by oral conjugated estrogens, 2.5 mg daily, or ethinyl estradiol, 20 mcg orally daily, for 3 weeks, with the addition of medroxyprogesterone acetate, 10 mg orally daily for the last 10 days of treatment, or a combination oral contraceptive daily for 3 weeks. This will thicken the endometrium and control the bleeding.

For women with ineffective results from medical management or desiring definitive therapy, surgical options can be considered. Heavy menstrual bleeding due to structural lesions (eg, fibroids, adenomyosis) is the most common indication for surgery. Minimally invasive procedural options for fibroids include uterine artery embolization and focused ultrasound ablation. Surgical options include myomectomy or hysterectomy. For women without structural abnormalities, endometrial ablation has similar results compared to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD in reducing menstrual blood loss. Hysteroscopic surgical approaches include endometrial ablation with laser photocoagulation or electrocautery. Nonhysteroscopic techniques include balloon thermal ablation, cryoablation, free-fluid thermal ablation, impedance bipolar radiofrequency ablation, and microwave ablation. The latter methods are well-adapted to outpatient therapy under local anesthesia. While hysterectomy was used commonly in the past for bleeding unresponsive to medical therapy, the low risk of complications and the good short-term results of both endometrial ablation and levonorgestrel-releasing IUD make them attractive alternatives to hysterectomy.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• If bleeding is not controlled with first-line therapy.

• If expertise is needed for a surgical procedure.

When to Admit

When to Admit

If bleeding is uncontrollable with first-line therapy or the patient is not hemodynamically stable.

Bryant-Smith AC et al. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 15;4:CD000249. [PMID: 29656433]

Munro MG et al; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The Two FIGO Systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Dec;143(3):393–408. [PMID: 30198563]

Singh S et al. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline No. 292. Abnormal uterine bleeding in pre-menopausal women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 May;40(5):e391–415. [PMID: 29731212]

POSTMENOPAUSAL UTERINE BLEEDING

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Any uterine bleeding in a postmenopausal woman (12 months or more following cessation of menstrual cycles).

Any uterine bleeding in a postmenopausal woman (12 months or more following cessation of menstrual cycles).

Postmenopausal bleeding of any amount always should be evaluated.

Postmenopausal bleeding of any amount always should be evaluated.

Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of the endometrium is an important tool in evaluating the cause of postmenopausal bleeding.

Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of the endometrium is an important tool in evaluating the cause of postmenopausal bleeding.

General Considerations

General Considerations

The most common causes are endometrial atrophy, endometrial proliferation or hyperplasia, endometrial or cervical cancer, and administration of estrogens without or with added progestin. Other causes include atrophic vaginitis, trauma, endometrial polyps, abrasion of the cervix associated with prolapse of the uterus, and blood dyscrasias.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The vulva and vagina should be inspected for areas of bleeding, ulcers, or neoplasms. Cervical cytology should be obtained, if indicated. Transvaginal sonography should be used to measure endometrial thickness. An endometrial stripe measurement of 4 mm or less indicates a low likelihood of hyperplasia or endometrial cancer. If the endometrial thickness is greater than 4 mm or there is a heterogeneous appearance to the endometrium, endometrial sampling is indicated. Sonohysterography may be helpful in determining if the endometrial thickening is diffuse or focal. If the thickening is global, endometrial biopsy or D&C is appropriate. If focal, guided sampling with hysteroscopy should be done.

Treatment

Treatment

Management options for simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia include surveillance, oral contraceptives, or progestin therapy. Surveillance may be used if the risk of occult cancer or progression to cancer is low and the inciting factor (eg, anovulation) has been eliminated. Progestin therapy may include cyclic or continuous therapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate, 10 mg/day orally, or norethindrone acetate, 5 mg/day orally) for 21 or 30 days of each month for 3 months or the use of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Repeat sampling should be performed if symptoms recur. For complex hyperplasia without atypia, options include progestin therapy with scheduled repeat endometrial sampling or hysterectomy. Hysterectomy is indicated for endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (also called endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia) or carcinoma of the endometrium.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Expertise in performing ultrasonography is required.

• Endometrial hyperplasia with atypia is present.

• Hysteroscopy is indicated.

Bar-On S et al. Is outpatient hysteroscopy accurate for the diagnosis of endometrial pathology among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women? Menopause. 2018 Feb;25(2):160–4. [PMID: 28763396]

Schramm A et al. Value of endometrial thickness assessed by transvaginal ultrasound for the prediction of endometrial cancer in patients with postmenopausal bleeding. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Aug;296(2):319–26. [PMID: 28634754]

Turnbull HL et al. Investigating vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women found to have an endometrial thickness of equal to or greater than 10 mm on ultrasonography. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Feb;295(2):445–50. [PMID: 27909879]

LEIOMYOMA OF THE UTERUS (Fibroid Tumor)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Irregular enlargement of the uterus (may be asymptomatic).

Irregular enlargement of the uterus (may be asymptomatic).

Heavy or irregular vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea.

Heavy or irregular vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea.

Pelvic pain and pressure.

Pelvic pain and pressure.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Uterine leiomyomas are the most common benign neoplasm of the female genital tract. They are discrete, round, firm, often multiple, uterine tumors composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue. The most convenient classification is by anatomic location: (1) intramural, (2) submucous, (3) subserous, and (4) cervical. Submucous myomas may become pedunculated and descend through the cervix into the vagina.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

In nonpregnant women, myomas are frequently asymptomatic. The two most common symptoms of uterine leiomyomas for which women seek treatment are AUB and pelvic pain or pressure. Occasionally, degeneration occurs, causing intense pain. Myomas that significantly distort the uterine cavity may affect fertility by interfering with implantation, rapidly distending in early pregnancy, or impairing uterine contractility.

B. Laboratory Findings

Iron deficiency anemia may result from blood loss.

C. Imaging

Ultrasonography will confirm the presence of uterine myomas and can be used sequentially to monitor growth. When multiple subserous or pedunculated myomas are being followed, ultrasonography is important to exclude ovarian masses. MRI can delineate intramural and submucous myomas accurately and is typically used prior to uterine artery embolization to determine fibroid size and location in relation to uterine blood supply. Hysterography or hysteroscopy can also confirm cervical or submucous myomas.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Irregular myomatous enlargement of the uterus must be differentiated from the similar, but symmetric enlargement that may occur with pregnancy or adenomyosis. Subserous myomas must be distinguished from ovarian tumors. Leiomyosarcoma is an unusual tumor occurring in 0.5% of women operated on for symptomatic myomas. It is very rare under the age of 40 but increases in incidence thereafter.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Nonsurgical Measures

Women who have small asymptomatic myomas can be managed expectantly and evaluated annually. In patients wishing to defer surgical management, nonhormonal therapies (such as NSAIDs and tranexamic acid) have been shown to decrease menstrual blood loss. Women with heavy bleeding related to fibroids often respond to estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives or the levonorgestrel IUD, although an IUD cannot be used with a distorted cavity. Hormonal therapies, such as GnRH agonists and selective progesterone receptor modulators (eg, low-dose mifepristone and ulipristal acetate), have been shown to reduce myoma volume, uterine size, and menstrual blood loss. Selective progesterone receptor modulators are not approved for fibroid treatment in the United States, however. Surgical intervention is based on the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility. Uterine size alone is not an indication for surgery. Cervical myomas larger than 3–4 cm in diameter or pedunculated myomas that protrude through the cervix can cause bleeding, infection, degeneration, pain, or urinary retention and often require removal. Submucous myomas can be removed by hysteroscopic resection.

Because the risk of surgical complications increases with the increasing size of the myoma, preoperative reduction of myoma size is sometimes desirable prior to hysterectomy. GnRH analogs such as depot leuprolide, 3.75 mg intramuscularly monthly, can be used preoperatively for 3- to 4-month periods to induce reversible hypogonadism, to temporarily reduce the size of myomas, and to reduce surrounding vascularity.

B. Surgical Measures

A variety of surgical measures are available for the treatment of myomas: myomectomy (hysteroscopic, laparoscopic, or abdominal) and hysterectomy (vaginal, laparoscopy-assisted vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal, or robotic). Myomectomy is the treatment of choice for women who wish to preserve fertility. Uterine artery embolization is a minimally invasive treatment for uterine fibroids. In uterine artery embolization, the goal is to block the blood vessels supplying the fibroids, causing them to shrink. Magnetic resonance–guided high-intensity focused ultrasound, myolysis/radiofrequency ablation, and laparoscopic or vaginal occlusion of uterine vessels are newer interventions, with a smaller body of evidence.

Prognosis

Prognosis

In women desiring future fertility, myomectomy can be offered, but patients should be counseled that recurrence is common, postoperative pelvic adhesions may impact fertility, and cesarean delivery may be necessary secondary to interruption of the myometrium. Approximately 80% of women have long-term improvement in symptoms following uterine artery embolization. Definitive surgical therapy (ie, hysterectomy) is curative.

When to Refer

When to Refer

Refer to a gynecologist for treatment of symptomatic leiomyomata.

When to Admit

When to Admit

For acute abdomen associated with an infarcted leiomyoma or for hemorrhage not controlled by outpatient measures.

Chudnoff S et al. Ultrasound-guided transcervical ablation of uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol 2019 Jan;133(1):13–22. [PMID: 30531573]

Donnez J et al. The current place of medical therapy in uterine fibroid management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Jan;46:57–65. [PMID: 29169896]

Havryliuk Y et al. Symptomatic fibroid management: systematic review of the literature. JSLS. 2017 Jul–Sep;21(3). [PMID: 28951653]

Murji A et al. Selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 26;4:CD010770. [PMID: 28444736]

Osuga Y et al. Oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist relugolix compared with leuprorelin injections for uterine leiomyomas: a randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Mar;133(3):423–33. [PMID: 30741797]

CERVICAL POLYPS

Cervical polyps commonly occur during the reproductive years, particularly after age 40, and are occasionally noted in postmenopausal women. The cause is not known, but inflammation may play an etiologic role. The principal symptoms are discharge and abnormal vaginal bleeding. However, abnormal bleeding should not be ascribed to a cervical polyp without sampling the endocervix and endometrium. The polyps are visible in the cervical os on speculum examination.

Cervical polyps must be differentiated from polypoid neoplastic disease of the endometrium, small submucous pedunculated myomas, large nabothian cysts, and endometrial polyps. Cervical polyps rarely contain foci of dysplasia (0.5%) or of malignancy (0.5%). Asymptomatic polyps in women under age 45 may be left untreated.

Treatment

Treatment

Cervical polyps can generally be removed in the office by avulsion with uterine packing forceps or ring forceps.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Polyp with a wide base present.

• Inability to differentiate endocervical from endometrial polyp.

ENDOMETRIOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Dysmenorrhea or pelvic pain is most common presenting complaint.

Dysmenorrhea or pelvic pain is most common presenting complaint.

Dyspareunia.

Dyspareunia.

Increased frequency among infertile women.

Increased frequency among infertile women.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Endometriosis is an aberrant growth of endometrium outside of the uterus, particularly in the dependent parts of the pelvis and in the ovaries. Its principal manifestations are chronic pain and infertility. While retrograde menstruation is the most widely accepted cause, its pathogenesis and natural course are not fully understood. The overall prevalence in the United States is 6–10%.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The clinical manifestations of endometriosis are variable and unpredictable in both presentation and course. Dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, and dyspareunia, are among the well-recognized manifestations. A significant number of women with endometriosis, however, remain asymptomatic and most women with endometriosis have a normal pelvic examination. However, in some women, pelvic examination can disclose tender nodules in the cul-de-sac or rectovaginal septum, uterine retroversion with decreased uterine mobility, uterine tenderness, or adnexal mass or tenderness.

Endometriosis must be distinguished from pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ovarian neoplasms, and uterine myomas. Bowel invasion by endometrial tissue may produce blood in the stool that must be distinguished from bowel neoplasm.

Imaging is useful mainly in the presence of a pelvic or adnexal mass. Transvaginal ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice to detect the presence of deeply penetrating endometriosis of the rectum or rectovaginal septum; MRI should be reserved for equivocal cases of rectovaginal or bladder endometriosis. A definitive diagnosis of endometriosis is made only by histology of lesions removed at surgery.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Medical Treatment

Although there is no conclusive evidence that NSAIDs improve the pain associated with endometriosis, these agents are reasonable options in appropriately selected patients. Medical treatment, using a variety of hormonal therapies, is effective in the amelioration of pain associated with endometriosis. Most of these regimens are designed to inhibit ovulation over 4–9 months and to lower hormone levels, thus preventing cyclic stimulation of endometriotic implants and inducing atrophy. The optimum duration of hormonal therapy is not clear, and their relative merits in terms of side effects and long-term risks and benefits show insignificant differences when compared with one another and even, in mild cases, with placebo. Commonly used medical regimens include the following:

1. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives are first-line treatment and can be given cyclically or continuously; prolonged suppression of ovulation often inhibits further stimulation of residual endometriosis, especially if taken after one of the therapies mentioned here. Any of the combination oral contraceptives, the contraceptive patch, or the vaginal ring may be used continuously. Breakthrough bleeding can be treated with conjugated estrogens, 1.25 mg orally daily for 1 week, or estradiol, 2 mg daily orally for 1 week. Alternatively, a short hormone-free interval to allow a withdrawal bleed can be used whenever bothersome breakthrough bleeding occurs.

2. Progestins, specifically oral norethindrone acetate and subcutaneous depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) have been approved by the FDA for treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. The etonogestrel implant has also been shown to decrease endometriosis-related pain.

3. Intrauterine progestin, using the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, has been shown to be effective in reducing endometriosis-associated pelvic pain, and it is recommended before surgery.

4. GnRH agonists are highly effective in reducing the pain syndromes associated with endometriosis. However, they are not superior to other methods such as combined hormonal contraceptives as first-line therapy. The GnRH analog (long-acting injectable leuprolide acetate, 3.75 mg intramuscularly monthly, used for 6 months) suppresses ovulation. Side effects of vasomotor symptoms and bone demineralization may be relieved by “add-back” therapy, such as conjugated equine estrogen, 0.625 mg orally daily, or norethindrone, 5 mg orally daily.

5. Danazol is an androgenic medication that has been used for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. It may be used for 4–6 months in the lowest dose necessary to suppress menstruation, usually 200–400 mg orally twice daily. However, danazol has a high incidence of androgenic side effects that are more severe than other medications available, including decreased breast size, weight gain, acne, and hirsutism.

6. Aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole or letrozole) in combination with conventional therapy have been evaluated with positive results in premenopausal women with endometriosis-associated pain and pain recurrence.

7. GnRH antagonists suppress pituitary gonadotropin production and create a hypoestrogenic state, like GnRH agonists, but they are effective immediately rather than requiring 7–14 days for GnRH suppression. Injectable and oral forms (eg, cetrorelix and elagolix, respectively) are available.

B. Surgical Measures

Surgical treatment of endometriosis—particularly extensive disease—is effective both in reducing pain and in promoting fertility. Laparoscopic ablation of endometrial implants significantly reduces pain. Ablation of implants and, if necessary, removal of ovarian endometriomas enhance fertility, although subsequent pregnancy rates are inversely related to the severity of disease. Women with disabling pain for whom childbearing is not a consideration can be treated definitively with total abdominal hysterectomy plus bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. In premenopausal women, hormone replacement may then be used to relieve vasomotor symptoms.

Prognosis

Prognosis

There is little systematic research regarding either the progression of the disease or the prediction of clinical outcomes. The prognosis for reproductive function in early or moderately advanced endometriosis appears to be good with conservative therapy. Hysterectomy, with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, often is regarded as definitive treatment of endometriosis associated with intractable pelvic pain, adnexal masses, or multiple previous ineffective conservative surgical procedures. However, symptoms may recur even after hysterectomy and oophorectomy.

When to Refer

When to Refer

Refer to a gynecologist for laparoscopic diagnosis or surgical treatment.

When to Admit

When to Admit

Rarely necessary except for acute abdomen associated with ruptured or bleeding endometrioma.

Brown J et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain in women with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 23;1:CD004753. [PMID: 28114727]

Fu J et al. Progesterone receptor modulators for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 25;7:CD009881. [PMID: 28742263]

Rafique S et al. Medical management of endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;60(3):485–96. [PMID: 28590310]

Singh SS et al. Surgical outcomes in patients with endometriosis: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019 Nov 9. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31718952]

Taylor HS et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377(1):28–40. [PMID: 28525302]

Vilasagar S et al. A practical guide to the clinical evaluation of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Feb;27(2):270–9. [PMID: 31669551]

PELVIC PAIN

1. Primary Dysmenorrhea

Primary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain associated with menstrual cycles in the absence of pathologic findings. Primary dysmenorrhea pain usually begins within 1–2 years after the menarche and may become progressively more severe. The frequency of cases increases up to age 20 and then decreases with both increasing age and parity. Fifty percent to 75% of women are affected by dysmenorrhea at some time and 5–6% have incapacitating pain.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Primary dysmenorrhea is low, midline, wave-like, cramping pelvic pain often radiating to the back or inner thighs. Cramps may last for 1 or more days and may be associated with nausea, diarrhea, headache, and flushing. The pain is produced by uterine vasoconstriction, anoxia, and sustained contractions mediated by prostaglandins. The pelvic examination is normal between menses; examination during menses may produce discomfort, but there are no pathologic findings.

Treatment

Treatment

NSAIDs (ibuprofen, ketoprofen, mefenamic acid, naproxen) and the cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor (celecoxib) are generally helpful. The medication should be started 1–2 days before expected menses. Symptoms can be suppressed with use of combined hormonal contraceptives, DMPA, etonogestrel subdermal implant (Nexplanon), or the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Continuous use of oral contraceptives can be used to suppress menstruation completely and prevent dysmenorrhea. For women who do not wish to use hormonal contraception, other therapies that have shown at least some benefit include local heat; thiamine, 100 mg/day orally; vitamin E, 200 units/day orally from 2 days prior to and for the first 3 days of menses; and high-frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

2. Other Categories of Pelvic Pain

Unlike primary dysmenorrhea, other causes of pelvic pain may or may not be associated with the menstrual cycle but are more likely to be associated with pelvic pathology. Conditions such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, fibroids, PID, or other anatomic abnormalities of the pelvic organs, including the bowel or bladder, may present with symptoms during the menstrual cycle.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The history and physical examination may suggest endometriosis, adenomyosis, or fibroids as causes of pelvic pain. Other causes include PID, tubo-ovarian abscess, submucous myoma(s), IUD use, cervical stenosis with obstruction, or blind uterine horn (rare). Careful review of bowel or bladder symptoms besides pain should be done to exclude another pelvic organ source.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Targeted physical examination may help identify the anatomic source of pelvic pain. PID should be considered in sexually active women with pelvic pain and examination findings of cervical motion tenderness, uterine, or adnexal tenderness without another explanation for the pain. Pelvic imaging is useful for diagnosing the presence of uterine fibroids or other anomalies. Adenomyosis (the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium) may be detected with ultrasound or MRI. Laparoscopy may help diagnose endometriosis or other pelvic abnormalities not visualized by imaging.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Specific Measures

Combined estrogen and progestin and progestin-only hormonal contraceptives are first-line therapies for alleviating the symptom of dysmenorrhea. Periodic use of analgesics, including the NSAIDs given for primary dysmenorrhea, may be beneficial, particularly in pelvic pain due to endometriosis. GnRH agonists are also an effective treatment of endometriosis, although their long-term use may be limited by cost or side effects. Adenomyosis may respond to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, uterine artery embolization, or hormonal approaches used to treat endometriosis, but hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment of choice for women for whom childbearing is not a consideration.

B. Surgical Measures

If disability is marked or prolonged, diagnostic laparoscopy is usually warranted. Definitive surgery depends on the degree of disability and the findings at operation. Uterine fibroids may be removed or treated by uterine artery embolization. Hysterectomy may be done if other treatments have not worked but is usually a last resort.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Standard therapy fails to relieve pain.

• Suspicion of pelvic pathology, such as endometriosis, leiomyomas, or adenomyosis.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Committee Opinion No. 770: Dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec;132(6):e249–258. [PMID: 30461694]

Bishop LA. Management of chronic pelvic pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;60(3):524–30. [PMID: 28742584]

Brown J et al. Oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 May 22;5:CD001019. [PMID: 29786828]

Carey ET et al. Updates in the approach to chronic pelvic pain: what the treating gynecologist should know. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec;62(4):666–76. [PMID: 31524660]

Ferrero S et al. Current and emerging treatment options for endometriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018 Jul;19(10):1109–25. [PMID: 29975553]

Matsushima T et al. Efficacy of hormonal therapies for decreasing uterine volume in patients with adenomyosis. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2018 Jul–Sep;7(3):119–23. [PMID: 30254953]

Oladosu FA et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: epidemiology, causes, and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Apr;218(4):390–400. [PMID: 28888592]

Smith SE et al. Interventional pain management and female pelvic pain: considerations for diagnosis and treatment. Semin Reprod Med. 2018 Mar;36(2):159–63. [PMID: 30566982]

PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

General Considerations

General Considerations

Pelvic organ prolapses, including cystocele, rectocele, and enterocele, are vaginal hernias commonly seen in multiparous women. Cystocele is a hernia of the bladder wall into the vagina, causing a soft anterior fullness. Cystocele may be accompanied by urethrocele, which is not a hernia but a sagging of the urethra following its detachment from the pubic symphysis during childbirth. Rectocele is a herniation of the terminal rectum into the posterior vagina, causing a collapsible pouch-like fullness. Enterocele is a vaginal vault hernia containing small intestine, usually in the posterior vagina and resulting from a deepening of the pouch of Douglas. Two or all three types of hernia may occur in combination. Risk factors may include vaginal birth, genetic predisposition, advancing age, prior pelvic surgery, connective tissue disorders, and increased intra-abdominal pressure associated with obesity or straining associated with chronic constipation or coughing.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse may include a sensation of a bulge or protrusion in the vagina, urinary or fecal incontinence, constipation, sense of incomplete bladder emptying, and dyspareunia. The cause of pelvic organ prolapse, including prolapse of the uterus, vaginal apex, and anterior or posterior vaginal walls, is likely multifactorial.

Treatment

Treatment

The type of therapy depends on the extent of prolapse and associated symptoms, impact on the patient’s quality of life, the patient’s age, and her desire for menstruation, pregnancy, and coitus.

A. General Measures

Supportive measures include a high-fiber diet and laxatives to improve constipation. Weight reduction in obese patients and limitation of straining and lifting are helpful. Pelvic muscle training (Kegel exercises) is a simple, noninvasive intervention that may improve pelvic function; it has demonstrated clear benefit for women with urinary or fecal symptoms, especially incontinence. Pessaries may reduce a cystocele, rectocele, or enterocele and are helpful in women who do not wish to undergo surgery or who are poor surgical candidates.

B. Surgical Measures

The most common surgical procedure is vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy with additional attention to restoring apical support after the uterus is removed, by suspension either by vaginal uterosacral or sacrospinous fixation or by abdominal sacral colpopexy. Since stress incontinence is common after vault suspension procedures, an anti-incontinence procedure should be considered. Surgical mesh placed transvaginally for pelvic organ prolapse repair was introduced into clinical practice in 2002, but in 2011 the FDA issued warnings about concerns for serious complications associated with this practice (including mesh erosion and pain). Use of these methods subsequently declined significantly. In April 2019, the US FDA withdrew its previous (2016) class III (high risk) approval of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of anterior compartment prolapse. Patients planning to have surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse should discuss all treatment options, including the risks and benefits of using surgical mesh, with their clinician. If the patient desires pregnancy, the same procedures for vaginal suspension can be performed without hysterectomy, though limited data on pregnancy outcomes or prolapse outcomes are available. Generally, surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse is reserved until after completion of childbearing. For elderly women who do not desire coitus, colpocleisis, the partial obliteration of the vagina, is surgically simple and effective. Uterine suspension with sacrospinous cervicocolpopexy may be an effective approach in older women who wish to avoid hysterectomy but preserve coital function. Women who have received transvaginal mesh for the surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse but who are having no symptoms or complications related to it should continue with their annual check-ups and other routine follow-up care. They should let their clinician know that they have a surgical mesh implant, especially if they plan to have another pelvic surgery or related medical procedure. In addition, they should notify their clinician if they develop symptoms such as persistent vaginal bleeding or discharge, pelvic or groin pain, or dyspareunia.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Refer to urogynecologist or gynecologist for incontinence evaluation.

• Refer if nonsurgical therapy is ineffective.

• Refer for removal of mesh if symptoms develop.

Coolen AWM et al. Primary treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: pessary use versus prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018 Jan;29(1):99–107. [PMID: 28600758]

Meriwether KV et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systemic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;219(2):129–46. [PMID: 29353031]

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Urogynecologic surgical mesh implants, April 16 2019. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants

Winkelman WD et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration statements about transvaginal mesh and changes in apical prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Oct;134(4):745–52. [PMID: 31503162]

PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME

General Considerations

General Considerations

The premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a recurrent, variable cluster of troublesome physical and emotional symptoms that develop during the 5 days before the onset of menses and subside within 4 days after menstruation occurs. PMS intermittently affects about 40% of all premenopausal women, primarily those 25–40 years of age. In about 5–8% of affected women, the syndrome may be severe. Although not every woman experiences all the symptoms or signs at one time, many describe bloating, breast pain, headache, swelling, irritability, aggressiveness, depression, inability to concentrate, libido change, lethargy, and food cravings. When emotional or mood symptoms predominate, along with physical symptoms, and there is a clear functional impairment with work or personal relationships, the term “premenstrual dysphoric disorder” (PMDD) may be applied. The pathogenesis of PMS/PMDD is still uncertain, and current treatment methods are mainly empiric. The clinician should provide support for both the patient’s emotional and physical distress, including the following:

1. Careful evaluation of the patient, with understanding, explanation, and reassurance.

2. Advice to keep a daily diary of all symptoms for 2–3 months, such as the Daily Record of Severity of Problems, to evaluate the timing and characteristics of her symptoms. If her symptoms occur throughout the month rather than in the 2 weeks before menses, she may have depression or other mental health problems instead of or in addition to PMS.

Treatment

Treatment

For mild to moderate symptoms, a program of aerobic exercise; reduction of caffeine, salt, and alcohol intake; an increase in dietary calcium (to 1200 mg/day), vitamin D, or magnesium, and complex carbohydrates in the diet; and use of alternative therapies such as acupuncture and herbal treatments may be helpful, although these interventions remain unproven.

Medications that prevent ovulation, such as hormonal contraceptives, may lessen physical symptoms. These include continuous combined hormonal contraceptive methods (pill, patch, or vaginal ring); or GnRH agonist with “add-back” therapy (eg, conjugated equine estrogen, 0.625 mg orally daily with medroxyprogesterone acetate, 2.5–5 mg orally daily).

When mood disorders predominate, several serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to be effective in relieving tension, irritability, and dysphoria with few side effects. First-line medication therapy includes serotonergic antidepressants (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine) either daily or only on symptom days. There are few data to support the use of calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B6 supplementation. There is insufficient evidence to support cognitive behavioral therapy.

Naheed B et al. Non-contraceptive oestrogen-containing preparations for controlling symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar 3;3:CD010503. [PMID: 28257559]

Yonkers KA et al. Premenstrual disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218(1):68–74. [PMID: 28571724]

MENOPAUSAL SYNDROME

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Menopause is a retrospective diagnosis after 12 months of amenorrhea.

Menopause is a retrospective diagnosis after 12 months of amenorrhea.

Approximately 80% of women will experience hot flushes and night sweats.

Approximately 80% of women will experience hot flushes and night sweats.

Elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and low estradiol can help confirm the diagnosis.

Elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and low estradiol can help confirm the diagnosis.

General Considerations

General Considerations

The term “menopause” denotes the final cessation of menstruation, either as a normal part of aging or as the result of surgical removal of both ovaries. In a broader sense, as the term is commonly used, it denotes a 1- to 3-year period during which a woman adjusts to a diminishing, and then absent, menstrual flow and the physiologic changes that may be associated with lowered estrogen levels—hot flushes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness.

The average age at menopause in Western societies is 51 years. Premature menopause is defined as ovarian failure and menstrual cessation before age 40; this often has a genetic or autoimmune basis. Surgical menopause due to bilateral oophorectomy is common and can cause more severe symptoms owing to the sudden rapid drop in sex hormone levels.

There is no objective evidence that cessation of ovarian function is associated with severe emotional disturbance or personality changes. However, mood changes toward depression and anxiety can occur at this time. Disruption of sleep patterns associated with the menopause can affect mood and concentration and cause fatigue. Furthermore, the time of menopause often coincides with other major life changes, such as departure of children from the home, a midlife identity crisis, or divorce.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

1. Cessation of menstruation—Menstrual cycles generally become irregular as menopause approaches. Anovulatory cycles occur more often, with irregular cycle length and occasional menorrhagia. Menstrual flow usually diminishes in amount owing to decreased estrogen secretion, resulting in less abundant endometrial growth. Finally, cycles become longer, with missed periods or episodes of spotting only. When no bleeding has occurred for 1 year, the menopausal transition can be said to have occurred. Any bleeding after 6 months of the cessation of menses warrants investigation by endometrial curettage or aspiration to rule out endometrial cancer.

2. Hot flushes—Hot flushes (feelings of intense heat over the trunk and face, with flushing of the skin and sweating) occur in over 80% of women as a result of the decrease in ovarian hormones. Hot flushes can begin before the cessation of menses. Menopausal vasomotor symptoms last longer than previously thought, and there are ethnic differences in the duration of symptoms. Vasomotor symptoms last more than 7 years in more than 50% of the women. African-American women report the longest duration of vasomotor symptoms. The etiology of hot flushes is unknown. Occurring at night, they often cause sweating and insomnia and result in fatigue on the following day.

3. Vaginal atrophy—With decreased estrogen secretion, thinning of the vaginal mucosa and decreased vaginal lubrication occur and may lead to dyspareunia. The introitus decreases in diameter. Pelvic examination reveals pale, smooth vaginal mucosa and a small cervix and uterus. The ovaries are not normally palpable after the menopause.

4. Osteoporosis—Osteoporosis may occur as a late sequela of menopause. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for osteoporosis beginning at age 65. The most recent June 2018 USPSTF recommendation summary can be found at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/osteoporosis-screening1.

B. Laboratory Findings

Serum FSH, luteinizing hormone (LH), and estradiol levels are of little diagnostic value because of unpredictable variability during the menopausal transition but can provide confirmation if the FSH remains consistently elevated and the estradiol, low. Vaginal cytologic examination will show a low estrogen effect with predominantly parabasal cells, indicating lack of epithelial maturation due to hypoestrogenism.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Natural Menopause

Education and support from health providers, midlife discussion groups, and reading material will help most women having difficulty adjusting to the menopause. Physiologic symptoms can be treated with both hormonal or nonhormonal therapies. Hormonal replacement therapy has been shown to be effective in treating perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms but is not effective in prevention of chronic conditions such as coronary heart disease.

1. Vasomotor symptoms—For women with mild symptoms, lifestyle modification, such as increased hydration, decreased caffeine consumption, tobacco cessation, and dressing in layers are first-line therapies to be undertaken before consideration of other nonhormonal or hormonal medical treatments. For women with moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms, hormone replacement estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens are the most effective approach to symptom relief. Conjugated estrogens, 0.3 mg, 0.45 mg, or 0.625 mg; 17-beta-estradiol, 0.5 or 1 mg; or estrone sulfate, 0.625 mg can be given once daily orally; or estradiol can be given transdermally as skin patches that are changed once or twice weekly and secrete 0.05–0.1 mg of hormone daily. Unless the patient has undergone hysterectomy, a combination regimen of an estrogen with a progestin such as medroxyprogesterone, 1.5 or 2.5 mg, or norethindrone, 0.1, 0.25, or 0.5 mg, should be used to prevent endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. There is also a patch available containing estradiol and the progestin levonorgestrel. Oral hormones can be given in several different regimens. Give estrogen on days 1–25 of each calendar month, with 5–10 mg of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate added on days 14–25. Withhold hormones from day 26 until the end of the month, when the endometrium will be shed, producing a light, generally painless monthly period. Alternatively, give the estrogen along with a progestin daily, without stopping. This regimen causes some initial bleeding or spotting, but within a few months it produces an atrophic endometrium that will not bleed. If the patient has had a hysterectomy, a progestin need not be given with the estrogen.

Postmenopausal women generally should not use combination progestin-estrogen therapy for more than 3 or 4 years. Women who cannot find relief with alternative approaches may wish to consider continuing use of combination therapy after a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits. Alternatives to hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine, 12.5 mg or 25 mg/day orally, or venlafaxine, 75 mg/day orally. Gabapentin, an antiseizure medication, is also effective at 900 mg/day orally. Clonidine given orally or transdermally, 100–150 mcg daily, may also reduce the frequency of hot flushes, but its use is limited by side effects, including dry mouth, drowsiness, and hypotension. There is some evidence that soy isoflavones may be effective in treating menopausal symptoms.

2. Vaginal atrophy—A vaginal ring containing 2 mg of estradiol can be left in place for 3 months and is suitable for long-term use. Although serum estrogen level increases associated with vaginal rings are lower than other routes of administration, it is recommended that the ring be used with caution. ACOG suggests that vaginal estrogen is an option for urogenital symptoms even in breast cancer survivors. Short-term use of estrogen vaginal cream will relieve symptoms of atrophy, but because of variable absorption, therapy with either the vaginal ring or systemic hormone replacement is preferable. A low-dose estradiol tablet (10 mcg) is available and is inserted in the vagina daily for 2 weeks and then twice a week for long-term use. Testosterone propionate 1–2%, 0.5–1 g, in a vanishing cream base used in the same manner is also effective if estrogen is contraindicated. A bland lubricant such as unscented cold cream or water-soluble gel can be helpful at the time of coitus.

3. Osteoporosis—(See also discussion in Chapter 26.) Women should ingest at least 800 mg of calcium daily throughout life. Nonfat or low-fat milk products, calcium-fortified orange juice, green leafy vegetables, corn tortillas, and canned sardines or salmon consumed with the bones are good dietary sources. Vitamin D, at least 800 international units/day from food, sunlight, or supplements, is necessary to enhance calcium absorption and maintain bone mass. A daily program of energetic walking and exercise to strengthen the arms and upper body helps maintain bone mass. Screening bone densitometry is recommended for women beginning at age 65 (see Chapter 1). Women most at risk for osteoporotic fractures should consider bisphosphonates, raloxifene, or hormone replacement therapy. This includes white and Asian women, especially if they have a family history of osteoporosis, are thin, short, cigarette smokers, have a history of hyperthyroidism, use corticosteroid medications long term, or are physically inactive.

B. Risks of Hormone Therapy

Double-blind, randomized, controlled trials have shown no overall cardiovascular benefit with estrogen-progestin replacement therapy in a group of postmenopausal women, including women both with and without established coronary disease. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial and in the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS), the overall health risks (increased risk of coronary heart events; strokes; thromboembolic disease; gallstones; and breast cancer, including an increased risk of mortality from breast cancer) exceeded the benefits from the long-term use of combination estrogen and progesterone. Ancillary analysis of the WHI study showed that not only did estrogen-progestin hormone replacement therapy not benefit cognitive function, but there was a small unanticipated increased risk of cognitive decline in that group compared with women in the placebo group. The unopposed estrogen arm of the WHI trial demonstrated a decrease in the risk of hip fracture, a small but not significant decrease of breast cancer, but an increased risk of stroke and no evidence of protection from coronary heart disease. The study also showed a small increase in the combined risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia with estrogen use compared with placebo, similar to the estrogen-progestin arm. Women who have been receiving long-term estrogen-progestin hormone replacement therapy, even in the absence of complications, should be encouraged to stop, especially if they do not have menopausal symptoms. However, the risks appear to be lower in women starting therapy at the time of menopause and higher in previously untreated women starting therapy long after menopause. Therapy should be individualized as the risk-benefit profile varies with age and individual risk factors. (See also discussions of estrogen and progestin replacement therapy in Chapter 26.)

C. Surgical Menopause

The abrupt hormonal decrease resulting from oophorectomy generally results in severe vasomotor symptoms and rapid onset of dyspareunia and osteoporosis unless treated. If not contraindicated, estrogen replacement is generally started immediately after surgery. Conjugated estrogens 1.25 mg orally, estrone sulfate 1.25 mg orally, or estradiol 2 mg orally is given for 25 days of each month. After age 45–50 years, this dose can be tapered to 0.625 mg of conjugated estrogens or equivalent.

Del Carmen MG et al. Management of menopausal symptoms in women with gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Aug;146(2):427–35. [PMID: 28625396]

Gartlehner G et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2017 Dec 12;318(22):2234–49. [PMID: 29234813]

The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017 Jul;24(7):728–53. [PMID: 28650869]

POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Clinical or biochemical evidence of hyper-androgenism.

Clinical or biochemical evidence of hyper-androgenism.

Oligoovulation or anovulation.

Oligoovulation or anovulation.

Polycystic ovaries on ultrasonography.

Polycystic ovaries on ultrasonography.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder of unknown etiology affecting 5–10% of reproductive age women. PCOS is characterized by chronic anovulation, polycystic ovaries, and hyperandrogenism. It is associated with hirsutism and obesity as well as an increased risk of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome. Unrecognized or untreated PCOS is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The Rotterdam Criteria identify androgen production, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovaries as the key diagnostic features of the disorder in adult women; the emerging consensus is that at least two of these features must be present for diagnosis. The classification system has been endorsed by the National Institutes of Health.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

PCOS often presents as a menstrual disorder (ranging from amenorrhea to menorrhagia) and infertility. Skin disorders due to peripheral androgen excess, including hirsutism and acne, are common. Patients may also show signs of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, and these women are at increased risk for early-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome. Patients who do become pregnant are at increased risk for perinatal complications, such as gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. In addition, they have an increased long-term risk of endometrial cancer secondary to unopposed estrogen secretion.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Anovulation in the reproductive years may also be due to (1) premature ovarian failure (high FSH and LH levels); (2) functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, often associated with rapid weight loss or extreme physical exertion (low to normal FSH and LH levels for age); (3) discontinuation of hormonal contraceptives (return to ovulation typically occurs within 90 days); (4) pituitary adenoma with elevated prolactin (galactorrhea may or may not be present); and (5) hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. To rule out other etiologies in women with suspected PCOS, serum FSH, LH, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone should be checked. Because of the high risk of insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, all women with suspected PCOS should have a hemoglobin A1C and fasting glucose along with a lipid profile. Women with clinical evidence of androgen excess should have total testosterone, free (bioavailable) testosterone, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone measured. Women with stigmata of Cushing syndrome should have a 24-hour urinary free cortisol or a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia and androgen-secreting adrenal tumors also tend to have high circulating androgen levels and anovulation with polycystic ovaries; these disorders must also be ruled out in women with presumed PCOS and high serum androgens.

Treatment

Treatment

In obese patients with PCOS, weight reduction and exercise are often effective in reversing the metabolic effects and in inducing ovulation. For those women who do not respond to weight loss and exercise, metformin therapy may be helpful. Metformin is beneficial for metabolic or glucose abnormalities, and it can improve menstrual function. Metformin has little or no benefit in the treatment of hirsutism, acne, or infertility. Contraceptive counseling should be offered to prevent unplanned pregnancy in case of a return of ovulatory cycles. For women who are seeking pregnancy and remain anovulatory, clomiphene or other medications can be used for ovarian stimulation (see section on Infertility below). Clomiphene is the first-line therapy for infertility. If induction of ovulation fails, treatment with gonadotropins, but at low dose to lower the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, may be successful. Second-line therapies such as use of aromatase inhibitors or laparoscopic “ovarian drilling” are of unproved benefit. Women with PCOS are at greater risk than normal women for twin gestation with ovarian stimulation.

If the patient does not desire pregnancy and does not want or is not a candidate for contraception, then medroxyprogesterone acetate, 10 mg/day orally for the first 10 days of every 1–3 months, should be given to ensure regular shedding of the endometrium and thus avoid endometrial hyperplasia. If contraception is desired, combination hormonal contraceptives (pill, ring, or patch) can be used; this is also useful in controlling hirsutism, for which treatment must be continued for 6–12 months before results are seen. The levonorgestrel-releasing IUD is another option to minimize uterine bleeding and protect against endometrial hyperplasia, but unlike the combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, the IUD does not help control hirsutism.

Spironolactone is useful for hirsutism in doses of 25 mg three or four times daily. Flutamide, 125–250 mg orally daily, and finasteride, 5 mg orally daily, are also effective for treating hirsutism. Because these three agents are potentially teratogenic, they should be used only in conjunction with secure contraception. Topical eflornithine cream applied to affected facial areas twice daily for 6 months may be helpful in most women. Hirsutism may also be managed with depilatory creams, electrolysis, and laser therapy. The combination of laser therapy and topical eflornithine may be particularly effective.

Weight loss, exercise, and treatment of unresolved metabolic derangements are important in preventing cardiovascular disease. Women with PCOS should be managed aggressively and should have regular monitoring of lipid profiles and glucose. In adolescent patients with PCOS, hormonal contraceptives and metformin are treatment options.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• If expertise in diagnosis is needed.

• If patient is infertile.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 194: Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;131(6):e157–71. [PMID: 29794677]

Bednarska S et al. The pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: what’s new? Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017 Mar–Apr;26(2):359–67. [PMID: 28791858]

Gadalla MA et al. Medical and surgical treatment of reproductive outcomes in polycystic ovary syndrome: an overview of systematic reviews. Int J Fertil Steril. 2020 Jan;13(4):257–70. [PMID: 31710185]

INFERTILITY

A couple is said to be infertile if pregnancy does not result after 1 year of normal sexual activity without contraception. About 20% of couples experience infertility at some point in their reproductive lives; the incidence of infertility increases with age, with a decline in fertility beginning in the early 30s and accelerating in the late 30s. The male partner contributes to about 40% of cases of infertility, and a combination of factors is common. The most recent data from the CDC National Survey of Family Growth noted that 12% of women in the United States aged 15–44 have impaired fecundity.

A. Initial Testing

During the initial interview, the clinician can present an overview of infertility and discuss an evaluation and management plan. Private consultations with each partner separately are then conducted, allowing appraisal of psychosexual adjustment without embarrassment or criticism. Pertinent details (eg, sexually transmitted infection history or prior pregnancies) must be obtained. The ill effects of cigarettes, alcohol, and other recreational drugs on male fertility should be discussed. Prescription medications that impair male potency and factors that may lead to scrotal hyperthermia, such as tight underwear or frequent use of saunas or hot tubs, should be discussed. The gynecologic history should include the menstrual pattern, the use and types of contraceptives, frequency and success of coitus, and correlation of intercourse with time of ovulation. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine provides patient information on the infertility evaluation and treatment (https://www.reproductivefacts.org/topics/topics-index/infertility/).

General physical and genital examinations are performed on the female partner. Basic laboratory studies include assessment of ovarian reserve (eg, antimüllerian hormone, and day 3 FSH and estradiol) and thyroid function tests. If the woman has regular menses with minimal symptoms, the likelihood of ovulatory cycles is very high. A luteal phase serum progesterone above 3 ng/mL establishes ovulation. Couples should be advised that coitus resulting in conception occurs during the 6-day window around the day of ovulation. Ovulation predictor kits have largely replaced basal body temperatures for predicting ovulation, but temperature charting is a natural and inexpensive way to identify most fertile days. Basal body temperature charts cannot predict ovulation; they can only retrospectively confirm that ovulation occurred.

A semen analysis should be completed to rule out a male factor for infertility (see Chapter 29).

B. Further Testing

1. Gross deficiencies of sperm (number, motility, or appearance) require a repeat confirmatory analysis. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection is the treatment option available for sperm deficiencies except for azoospermia (absence of sperm). Intracytoplasmic sperm injection requires the female partner to undergo in vitro fertilization (IVF).

2. A screening pelvic ultrasound and hysterosalpingography to identify uterine cavity or tubal anomalies should be performed. Hysterosalpingography using an oil dye is performed within 3 days following the menstrual period if structural abnormalities are suspected. This radiographic study will demonstrate uterine abnormalities (septa, polyps, submucous myomas) and tubal obstruction. Oil-based (versus water-soluble) contrast media may improve pregnancy rates but reports of complications using oil-based media have resulted in a decrease in its usage. Women who have had prior pelvic inflammation should receive doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily, beginning immediately before and for 7 days after the radiographic study. IVF is recommended as the primary treatment option for tubal factor infertility. Surgery can be considered in women with mild tubal disease, but no rigorous research has evaluated surgical outcomes compared to IVF or expectant management.

3. Absent or infrequent ovulation requires additional laboratory evaluation. Elevated FSH and LH levels and low estradiol levels indicate ovarian insufficiency. Elevated LH levels in the presence of normal FSH levels may indicate the presence of polycystic ovaries. Elevation of blood prolactin levels suggests a pituitary adenoma. Women over age 35 may require further assessment of ovarian reserve. A markedly elevated FSH (greater than 15–20 international units/L) on day 3 of the menstrual cycle suggests inadequate ovarian reserve. Although less widely used clinically, a clomiphene citrate challenge test, with measurement of FSH on day 10 after administration of clomiphene from days 5–9, can help confirm a diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve. The number of antral follicles during the early follicular phase of the cycle can provide useful information about ovarian reserve and can confirm serum testing. An antimüllerian hormone level can be measured at any time during the menstrual cycle and is less likely to be affected by hormones.

4. If all of the above testing is normal, unexplained infertility is diagnosed. In approximately 25% of women whose basic evaluation is normal, the first-line therapy is usually controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (usually with clomiphene citrate) and intrauterine insemination. IVF may be recommended as second-line therapy.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Medical Measures

Fertility may be restored by treatment of endocrine abnormalities, particularly hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Women who are anovulatory as a result of low body weight or exercise may become ovulatory when they gain weight or decrease their exercise levels; conversely, obese women who are anovulatory may become ovulatory with loss of even 5–10% of body weight.

B. Surgical Measures

Excision of ovarian tumors or ovarian foci of endometriosis can improve fertility. Microsurgical relief of tubal obstruction due to salpingitis or tubal ligation will reestablish fertility in a significant number of cases, although with severe disease or proximal obstruction, IVF is preferable. Peritubal adhesions or endometriotic implants often can be treated via laparoscopy.

In a male with a varicocele, sperm characteristics may be improved following surgical treatment. For men who have sperm production but obstructive azoospermia, trans-epidermal sperm aspiration or microsurgical epidermal sperm aspiration has been successful.

C. Induction of Ovulation

1. Clomiphene citrate—Clomiphene citrate stimulates gonadotropin release, especially FSH. It acts as a selective estrogen receptor modulator, similar to tamoxifen and raloxifene, and binds to the estrogen receptor. The body perceives a low level of estrogen, decreasing the negative feedback on the hypothalamus, and there is an increased release of FSH and LH. When FSH and LH are present in the appropriate amounts and timing, ovulation occurs.

After a normal menstrual period or induction of withdrawal bleeding with progestin, clomiphene 50 mg orally should be given daily for 5 days, typically on days 3–7 of the cycle. If ovulation does not occur, the clomiphene dosage is increased to 100 mg orally daily for 5 days. If ovulation still does not occur, the course is repeated with 150 mg orally daily for 5 days and then 200 mg orally daily for 5 days. The maximum dosage is 200 mg orally daily. Ovulation and appropriate timing of intercourse can be facilitated with the addition of chorionic gonadotropin, 10,000 units intramuscularly. Monitoring of the follicles by transvaginal ultrasound is usually necessary to time the hCG injection appropriately. The rate of ovulation following this treatment is 90% in the absence of other infertility factors. The pregnancy rate is high. Twinning occurs in 5% of these pregnancies, but three or more fetuses are rare (less than 0.5% of cases). Pregnancy is most likely to occur within the first three ovulatory cycles, and unlikely to occur after cycle six. In addition, several studies have suggested a twofold to threefold increased risk of ovarian cancer with the use of clomiphene for more than 1 year, so treatment with clomiphene is usually limited to a maximum of six cycles.

2. Letrozole—The aromatase inhibitor letrozole appears to be at least as effective as clomiphene for induction of ovulation in women with PCOS. There is a reduced risk of multiple pregnancy, a lack of antiestrogenic effects, and a reduced need for ultrasound monitoring. The dose of letrozole is 5–7.5 mg daily, starting on day 3 of the menstrual cycle. In women who have a history of estrogen dependent tumors, such as breast cancer, letrozole is preferred over other agents because the estrogen levels with this medication are much lower.

3. Cabergoline or bromocriptine—If prolactin levels are elevated, an evaluation for a pituitary mass should be conducted. In the absence of a pituitary mass, cabergoline or bromocriptine may be used if prolactin levels are elevated and there is no withdrawal bleeding following progesterone administration (otherwise, clomiphene is used). The initial cabergoline dosage is 2.5 mg orally once daily, increased to 2.5 mg two or three times daily by 1.25 mg increments of cabergoline. The medication is discontinued once pregnancy occurs. Cabergoline causes fewer adverse effects than bromocriptine. However, it is much more expensive. Cabergoline is often used in patients who cannot tolerate the adverse effects of bromocriptine or who do not respond to bromocriptine.

4. Human menopausal gonadotropins (hMG) or recombinant FSH—hMG or recombinant FSH is indicated in cases of hypogonadotropism and most other types of anovulation resistant to clomiphene treatment. Because of the complexities, laboratory tests, and expense associated with this treatment, these patients should be referred to an infertility specialist.

D. Treatment of Endometriosis

See above.

E. Artificial Insemination in Azoospermia

If azoospermia is present, artificial insemination by a donor usually results in pregnancy, assuming female function is normal. The use of frozen sperm provides the opportunity for screening for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV infection.

F. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART)

Couples who have not responded to traditional infertility treatments, including those with tubal disease, severe endometriosis, oligospermia, and immunologic or unexplained infertility, may benefit from ART. Gamete intrafallopian transfer and zygote intrafallopian transfer are rarely performed, although they may be an option in a few selected patients. These techniques are complex and require a highly organized team of specialists. All ART procedures involve ovarian stimulation to produce multiple oocytes, oocyte retrieval by transvaginal sonography–guided needle aspiration, and handling of the oocytes outside the body. With IVF, the eggs are fertilized in vitro and the embryos transferred to the uterus. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection allows fertilization with a single sperm. While originally intended for couples with male factor infertility, it is now used in two-thirds of all IVF procedures in the United States.

The chance of a multiple gestation pregnancy (ie, twins, triplets) is increased in all assisted reproductive procedures, increasing the risk of preterm delivery and other pregnancy complications. To minimize this risk, most infertility specialists recommend transferring only one embryo in appropriately selected patients with a favorable prognosis. In women with prior failed IVF cycles who are over the age of 40 who have poor embryo quality, up to four embryos may be transferred. In the event of a multiple gestation pregnancy, a couple may consider selective reduction to avoid the medical issues generally related to multiple births. This issue should be discussed with the couple before embryo transfer.

Prognosis

Prognosis

The prognosis for conception and normal pregnancy is good if minor (even multiple) disorders can be identified and treated; it is poor if the causes of infertility are severe, untreatable, or of prolonged duration (over 3 years).

It is important to remember that in the absence of identifiable causes of infertility, 60% of couples will achieve a spontaneous pregnancy within 3 years. Couples in which the woman is younger than 35 years who do not achieve pregnancy within 1 year of trying may be candidates for infertility treatment, and within 6 months for women age 35 years and older. Also, offering appropriately timed information about adoption is considered part of a complete infertility regimen.

When to Refer

When to Refer

Refer to reproductive endocrinologist if ART is indicated, or surgery is required.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 781: Infertility workup for the women’s health specialist. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jun;133(6):e377–84. [PMID: 31135764]

Chua SJ et al. Surgery for tubal infertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 23;1:CD006415. [PMID: 28112384]

Hanson B et al. Female infertility, infertility-associated diagnoses, and comorbidities: a review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017 Feb;34(2):167–77. [PMID: 27817040]

Jeelani R et al. Imaging and the infertility evaluation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;60(1):93–107. [PMID: 28106643]

CONTRACEPTION

Unintended pregnancies are a worldwide problem but disproportionately impact developing countries. Studies estimate that 40% of the 213 million pregnancies that occurred in 2012 were unintended. Globally, 50% ended in abortion, 13% ended in miscarriage, and 38% resulted in an unplanned birth. It is important for primary care providers to educate their patients about the benefits of contraception and to provide options that are appropriate and desirable for the patient.

1. Oral Contraceptives

A. Combined Oral Contraceptives

1. Efficacy and methods of use—Combined oral contraceptives have a perfect use failure rate of 0.3% and a typical use failure rate of 8%. Their primary mode of action is suppression of ovulation. The pills can be initially started on the first day of the menstrual cycle, the first Sunday after the onset of the cycle, or on any day of the cycle. If started more than 5 days after the first day of the cycle, a backup method should be used for the first 7 days. If an active pill is missed at any time, and no intercourse occurred in the past 5 days, two pills should be taken immediately and a backup method should be used for 7 days. If intercourse occurred in the previous 5 days, emergency contraception should be offered, and the pills restarted the following day. A backup method should be used for 5 days.