34

Spirochetal Infections

Susan S. Philip, MD, MPH

SYPHILIS

NATURAL HISTORY & PRINCIPLES OF DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT

Syphilis is a complex infectious disease caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochete capable of infecting almost any organ or tissue in the body and causing protean clinical manifestations (Table 34–1). Transmission occurs most frequently during sexual contact (including oral sex) or via the placenta from mother to fetus (congenital syphilis). The risk of acquiring syphilis after unprotected sex with an individual with infectious syphilis is approximately 30–50%. Rarely, it can also be transmitted through nonsexual contact or blood transfusion.

Table 34–1. Stages of syphilis and common clinical manifestations.

Primary syphilis

Chancre: painless ulcer with clean base and firm indurated borders

Regional lymphadenopathy

Secondary syphilis

Skin and mucous membranes

Rash: diffuse (may include palms and soles), macular, papular, pustular, and combinations

Condylomata lata

Mucous patches: painless, silvery ulcerations of mucous membrane with surrounding erythema

Generalized lymphadenopathy

Constitutional symptoms

Fever, usually low-grade

Malaise, anorexia

Arthralgias and myalgias

Central nervous system

Asymptomatic

Symptomatic

Meningitis

Cranial neuropathies (II–VIII)

Other

Ocular: iritis, iridocyclitis

Renal: glomerulonephritis, nephrotic syndrome

Hepatitis

Musculoskeletal: arthritis, periostitis

Tertiary (late) syphilis

Late benign (gummatous): granulomatous lesion usually involving skin, mucous membranes, and bones but any organ can be involved

Cardiovascular

Aortic regurgitation

Coronary ostial stenosis

Aortic aneurysm

Neurosyphilis

Asymptomatic

Meningovascular

Tabes dorsalis

General paresis

Note: Central nervous system involvement may occur at any stage.

The natural history of acquired syphilis is generally divided into two major stages: early (infectious) syphilis and late syphilis. Infectious syphilis includes primary lesions (chancre and regional lymphadenopathy) appearing during primary syphilis, secondary lesions (commonly involving skin and mucous membranes, occasionally bone, central nervous system [CNS], or liver) appearing during secondary syphilis (when dissemination of T pallidum produces systemic signs), relapsing lesions during early latency, and congenital lesions. The hallmark of these lesions is an abundance of spirochetes; tissue reaction is usually minimal. Late (tertiary) syphilis consists of so-called benign (gummatous) lesions involving skin, bones, and viscera; cardiovascular disease (principally aortitis); and a variety of CNS and ocular syndromes. These forms of syphilis are not contagious. The lesions contain few demonstrable spirochetes, but tissue reactivity (vasculitis, necrosis) is severe and suggestive of hypersensitivity phenomena. Between these stages are symptom-free latent phases. In early latent syphilis, which is defined as the symptom-free interval lasting up to 1 year after initial infection, infectious lesions can recur.

Public health efforts to control syphilis focus on the diagnosis and treatment of early (infectious) cases and their partners.

Most cases of syphilis in the United States continue to occur in men who have sex with men (MSM). Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 5.6 million total incident syphilis infections occur annually, with a prevalence of 1% among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics. Preventing congenital syphilis is a major public health goal for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and WHO.

COURSE & PROGNOSIS

The lesions associated with primary and secondary syphilis are self-limiting, even without treatment, and resolve with few or no residua. Ocular and otologic syphilis have been associated with permanent vision and hearing loss. Tertiary and congenital syphilis may be highly destructive and permanently disabling and may lead to death. While infection is almost never completely eradicated in the absence of treatment, most infections likely remain latent without sequelae, and only a small number of latent infections progress to further disease.

CLINICAL STAGES OF SYPHILIS

1. Primary Syphilis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Painless ulcer on genitalia, perianal area, rectum, pharynx, tongue, lip, or elsewhere.

Painless ulcer on genitalia, perianal area, rectum, pharynx, tongue, lip, or elsewhere.

Fluid expressed from ulcer contains T pallidum by immunofluorescence or darkfield microscopy.

Fluid expressed from ulcer contains T pallidum by immunofluorescence or darkfield microscopy.

Nontender enlargement of regional lymph nodes.

Nontender enlargement of regional lymph nodes.

Serologic nontreponemal and treponemal tests may be positive.

Serologic nontreponemal and treponemal tests may be positive.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

The typical lesion is the chancre at the site or sites of inoculation, most frequently located on the penis (Figure 34–1), labia, cervix, or anorectal region. Anorectal lesions are especially common among MSM. Chancres also occur occasionally in the oropharynx (lip, tongue, or tonsil) and rarely on the breast or finger or elsewhere. An initial small erosion appears 10–90 days (average, 3–4 weeks) after inoculation then rapidly develops into a painless superficial ulcer with a clean base and firm, indurated margins. This is associated with enlargement of regional lymph nodes, which are rubbery, discrete, and nontender. Healing of the chancre occurs without treatment, but a scar may form, especially with secondary bacterial infection. Multiple chancres may be present, particularly in HIV-positive patients. Although the “classic” ulcer of syphilis has been described as nontender, nonpurulent, and indurated, only 31% of patients have this triad.

Figure 34–1. Primary syphilis with a large chancre on the glans of the penis. The multiple small surrounding ulcers are part of the syphilis and not a second disease. (Used, with permission, from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

B. Laboratory Findings

1. Microscopic examination—In early (infectious) syphilis, darkfield microscopic examination by a skilled observer of fresh exudate from moist lesions or material aspirated from regional lymph nodes is up to 90% sensitive for diagnosis but is usually only available in select clinics that specialize in sexually transmitted infections.

An immunofluorescent staining technique for demonstrating T pallidum in dried smears of fluid taken from early syphilitic lesions is also performed in only a few laboratories.

T pallidum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is available in select research, referral, and public health laboratories and has the highest yield in primary and secondary lesions. Organisms can also be detected in blood, especially in congenital and secondary syphilis cases.

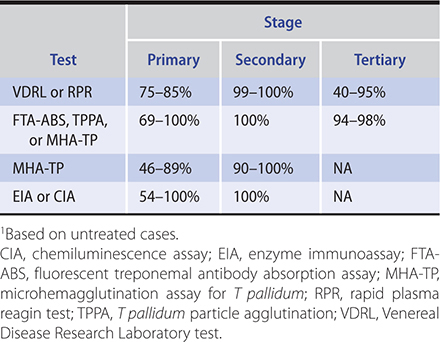

2. Serologic tests for syphilis—(Table 34–2.) Serologic tests (the mainstay of syphilis diagnosis) fall into two general categories: (1) Nontreponemal tests detect antibodies to lipoidal antigens present in the host after modification by T pallidum. (2) Treponemal tests use live or killed T pallidum as antigen to detect antibodies specific for pathogenic treponemes.

Table 34–2. Percentage of patients with positive serologic tests for syphilis.1

a. Nontreponemal antibody tests—The most commonly used nontreponemal antibody tests are the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests, which measure the ability of heated serum to flocculate a suspension of cardiolipin-cholesterol-lecithin. The flocculation tests are inexpensive, rapid, and easy to perform and have therefore been commonly used for initial screening. Quantitative expression of the reactivity of the serum, based on titration of dilutions of serum, is valuable in establishing the diagnosis and in evaluating the efficacy of treatment, since titers usually correlate with disease activity. A different, enzyme immunoassay (EIA)–based screening algorithm is discussed below.

Nontreponemal tests generally become positive 4–6 weeks after infection or 1–3 weeks after the appearance of a primary lesion; they are almost invariably positive in the secondary stage. These tests are nonspecific and may be positive in patients with non–sexually transmitted treponematoses. More important, false-positive serologic reactions are frequently encountered in a wide variety of conditions, including autoimmune diseases, infectious mononucleosis, malaria, febrile diseases, leprosy, injection drug use, infective endocarditis, advanced age, hepatitis C viral infection, and pregnancy. False-positive nontreponemal tests are usually of low titer and transient and may be distinguished from true positives by correlating with clinical findings and performing a treponemal specific-antibody test. False-negative results can be seen when very high antibody titers are present (the prozone phenomenon). If syphilis is strongly suspected and the nontreponemal test is negative, the laboratory should be instructed to dilute the specimen to detect a positive reaction.

Nontreponemal antibody titers are used to monitor the response to therapy and should decline over time. The rate of decline depends on various factors. In general, persons with repeat infections, higher initial titers, more advanced stages of disease, or those who are HIV-infected at the time of treatment have a slower seroconversion rate and are more likely to remain serofast (ie, titers decline but do not become nonreactive). The RPR and VDRL tests are equally reliable, but RPR titers tend to be higher than the VDRL. Thus, when these tests are used to follow disease activity, the same testing method should be used and preferably performed at the same laboratory.

b. Treponemal antibody tests—These tests measure antibodies capable of reacting with T pallidum antigens. Traditionally, they have been used to confirm a diagnosis following a positive nontreponemal test. The T pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) test has been one of the most commonly used treponemal tests, along with the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS). Newer treponemal tests used in reverse screening algorithms include the EIA and chemiluminescence assay (CIA).

In the traditional screening algorithm, the treponemal tests are used to confirm a positive nontreponemal test. Because of their sensitivity, particularly in the late stages of the disease, treponemal tests are also of value when there is clinical evidence of syphilis, but the nontreponemal serologic test for syphilis is negative. Treponemal tests are reactive in many patients with primary syphilis and in almost all patients with secondary syphilis (Table 34–2). Although a reactive treponemal-specific serologic test remains reactive throughout a patient’s life in most cases, it may (like nontreponemal antibody tests) revert to negative with adequate therapy. Final decisions about the significance of the results of serologic tests for syphilis must be based on a total clinical appraisal and may require expert consultation.

c. Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)- or chemiluminescence immunoassay (CIA)-based screening algorithms—Newer screening algorithms reverse the traditional test order and begin with an automated treponemal antibody test (eg, EIA or CIA) and then follow up with a nontreponemal test (RPR or VDRL) if the treponemal test is positive. This algorithm is faster and decreases labor costs to laboratories when compared with traditional screening.

The reverse algorithms can cause challenges in clinical management. A positive treponemal test with a negative RPR or VDRL may represent prior, treated syphilis; untreated latent syphilis; or a false-positive treponemal test. Such results should be evaluated with a second, different treponemal test as a “tie-breaker.” Reverse algorithms are recommended by several international organizations including the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections (IUSTI), but the CDC still recommends the traditional algorithm.

d. Rapid treponemal tests—A single rapid point of care treponemal test is approved for use in the United States, including in outreach and other nonlaboratory settings. Other tests are available internationally and are commonly used in limited-resource settings. Sensitivity ranges from 62% to 100% and specificity from 83% to 95%.

3. Polymerase chain reaction—In the United States, there are no FDA-approved T pallidum PCR test kits. However, kits are available as a laboratory-developed test in select research, referral, and public health laboratories and have the highest yield in primary and secondary lesions. There are no standards for these tests, but PCR has many advantages as a tool for direct detection, including high sensitivity and ability to use a wide range of clinical specimen types, including cerebrospinal fluid. PCR testing of blood has low sensitivity and is not recommended.

4. Cerebrospinal fluid examination (CSF)—See Neurosyphilis section.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The syphilitic chancre may be confused with genital herpes, chancroid (usually painful and uncommon in the United States), lymphogranuloma venereum, or neoplasm. Any genital ulcer should be considered a possible primary syphilitic lesion. Simultaneous evaluation for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 using PCR or culture should also be done in these cases.

Prevention & Screening

Prevention & Screening

Avoidance of sexual contact is the only completely reliable method of prevention but is an impractical public health measure. Latex or polyurethane condoms are effective but protect covered areas only. Men who have sex with men should be screened every 6–12 months, and as often as every 3 months in high-risk individuals (those who have multiple encounters with anonymous partners or who have sex in conjunction with the use of drugs). Every pregnant woman should be screened at the first prenatal visit and in some states with increasing congenital syphilis rates, again in the third trimester. A third screening at delivery is recommended if there are risk indicators, including poverty, sex work, illicit drug use, history of other sexually transmitted diseases, and residence in a community with high syphilis morbidity. Patients treated for other sexually transmitted diseases should also be tested for syphilis, and persons who have known or suspected sexual contact with patients who have syphilis should be evaluated and presumptively treated to abort development of infectious syphilis (see Treating Syphilis Contacts below).

Treatment

Treatment

A. Antibiotic Therapy

Penicillin remains the preferred treatment for syphilis, since there have been no documented cases of penicillin-resistant T pallidum (Table 34–3). In pregnant women, penicillin is the only option that reliably treats the fetus (see below).

Table 34–3. Recommended treatment for syphilis.1

There are some alternatives to penicillin for nonpregnant patients, including doxycycline. There are also limited data for ceftriaxone, although optimum dose and duration are not well defined. Azithromycin has been shown to be effective in some parts of the world but should be used with caution; it should not be used at all in MSM due to demonstrated resistance. All patients treated with a non-penicillin regimen must have particularly close clinical and serologic follow-up.

B. Managing Jarisch–Herxheimer Reaction

The Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction, manifested by fever and aggravation of the existing clinical picture in the hours following treatment, is a cytokine-mediated immunologic reaction to endotoxins released from the killed bacteria. It is most common in early syphilis, particularly secondary syphilis where it can occur in 66% of cases.

The reaction may be blunted by simultaneous administration of antipyretics, although no proven method of prevention exists. In cases with increased risk of morbidity due to the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction (including CNS or cardiac involvement and pregnancy), consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended. Patients should be reminded that the reaction does not signify an allergy to penicillin.

C. Local Measures (Mucocutaneous Lesions)

Local treatment is usually not necessary. No local antiseptics or topical antibiotics should be applied to a suspected syphilitic lesion until specimens for microscopy have been obtained.

D. Public Health Measures

Counsel patients with infectious syphilis to abstain from sexual activity for 7–10 days after treatment. All cases of syphilis must be reported to the appropriate local public health agency in order to identify and treat sexual contacts. In addition, all patients with syphilis who are not known to be HIV-infected should have an HIV test at the time of diagnosis. Those with a negative HIV test should be offered HIV preexposure prophylaxis (HIV PrEP) because syphilis is associated with an increased risk of future HIV acquisition.

E. Treating Syphilis Contacts

Patients who have been sexually exposed to infectious syphilis within the preceding 3 months may be infected but seronegative and thus should be treated as for early syphilis even if serologic tests are negative. Persons exposed more than 3 months previously should be treated based on serologic results; however, if the patient is unreliable for follow-up, empiric therapy is indicated. Contacts of the persons with syphilis should be evaluated for HIV PrEP.

Follow-Up Care

Follow-Up Care

Because treatment failures and reinfection may occur, patients treated for syphilis should be monitored clinically and serologically with nontreponemal titers every 3–6 months. In primary and secondary syphilis, titers had been expected to decrease fourfold by 12 months; however, up to 20% of patients may fail to decrease. Optimal management of these patients is unclear, but at a minimum, close clinical and serologic follow-up is indicated. In HIV-uninfected patients, an HIV test should be repeated; a thorough neurologic history and examination should be performed and lumbar puncture considered since unrecognized neurosyphilis can be a cause of treatment failure. If symptoms or signs persist or recur after initial therapy or there is a fourfold or greater increase in nontreponemal titers, the patient has been reinfected (more likely) or the therapy failed (if a non-penicillin regimen was used). In those individuals, an HIV test should be performed, a lumbar puncture done (unless reinfection is a certainty), and re-treatment given as indicated above.

2. Secondary Syphilis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Generalized maculopapular rash.

Generalized maculopapular rash.

Mucous membrane lesions.

Mucous membrane lesions.

Condylomata lata in moist skin areas.

Condylomata lata in moist skin areas.

Generalized nontender lymphadenopathy.

Generalized nontender lymphadenopathy.

Fever may be present.

Fever may be present.

Meningitis, hepatitis, osteitis, arthritis, iritis.

Meningitis, hepatitis, osteitis, arthritis, iritis.

Many treponemes in moist lesions by immunofluorescence or darkfield microscopy.

Many treponemes in moist lesions by immunofluorescence or darkfield microscopy.

Positive serologic tests for syphilis.

Positive serologic tests for syphilis.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The secondary stage of syphilis usually appears a few weeks (or up to 6 months) after development of the chancre, when dissemination of T pallidum produces systemic signs (fever, lymphadenopathy) or infectious lesions at sites distant from the site of inoculation. The most common manifestations are skin and mucosal lesions. The skin lesions are nonpruritic, macular, papular, pustular, or follicular (or combinations of any of these types, but generally not vesicular) and generalized; involvement of the palms and soles (Figure 34–2) occurs in 80% of cases. Annular lesions simulating ringworm may be observed. Transillumination may help identify faint rashes, or rashes in persons with darker skin color. Mucous membrane lesions may include mucous patches (Figure 34–3), which can be found on the lips, mouth, throat, genitalia, and anus. Specific lesions—condylomata lata (Figure 34–4)—are fused, weeping papules on the moist areas of the skin and mucous membranes and are sometimes mistaken for genital warts. Unlike the dry skin rashes, the mucous membrane lesions are highly infectious.

Figure 34–2. Papular squamous eruption of the hands and feet of a woman with secondary syphilis. (Used, with permission, from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Figure 34–3. Secondary syphilis mucous patch of the tongue. (Used with permission from Kenneth Katz, MD, MSc, MSCE.)

Figure 34–4. Secondary syphilis perianal condylomata lata. (Used with permission from Joseph Engelman, MD; San Francisco City Clinic.)

Meningeal (aseptic meningitis or acute basilar meningitis), hepatic, renal, bone, and joint invasion may occur, with resulting cranial nerve palsies, jaundice, nephrotic syndrome, and periostitis. Alopecia (moth-eaten appearance) and uveitis may also occur.

The serologic tests for syphilis are positive in almost all cases (see Primary Syphilis and Table 34–2). The moist cutaneous and mucous membrane lesions often show T pallidum on darkfield microscopic examination. A transient CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis (usually less than 50–100 cells/mcL) is seen in 40% of patients with secondary syphilis. There may be evidence of hepatitis or nephritis (immune complex type) as circulating immune complexes are deposited in blood vessel walls.

Skin lesions may be confused with the infectious exanthems, pityriasis rosea, and drug eruptions. Visceral lesions may suggest nephritis or hepatitis due to other causes.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment is as for primary syphilis unless CNS or ocular disease or neurologic signs or symptoms are present, in which case a lumbar puncture should be performed. If examination of the fluid is positive (see Spinal fluid examination for Neurosyphilis, below), treatment for neurosyphilis given (Table 34–3). See Primary Syphilis for follow-up care and treatment of contacts.

3. Latent Syphilis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Early latent syphilis: infection less than 1 year.

Early latent syphilis: infection less than 1 year.

Late latent syphilis: infection more than 1 year.

Late latent syphilis: infection more than 1 year.

No physical signs.

No physical signs.

History of syphilis with inadequate treatment.

History of syphilis with inadequate treatment.

Positive serologic tests for syphilis.

Positive serologic tests for syphilis.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Latent syphilis is the clinically quiescent phase in the absence of primary or secondary lesions; the diagnosis is made by positive serologic tests. Early latent syphilis is defined as the first year after primary infection and may relapse to secondary syphilis if undiagnosed or inadequately treated. Relapse is almost always accompanied by a rising titer in quantitative serologic tests; indeed, a rising titer may be the first or only evidence of relapse. About 90% of relapses occur during the first year after infection.

Early latent infection can be diagnosed if there was documented seroconversion or a fourfold increase in nontreponemal titers in the past 12 months; the patient can recall symptoms of primary or secondary syphilis; or the patient had a sex partner with documented primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis.

After the first year of latent syphilis, the patient is said to be in the late latent stage and noninfectious to sex partners. Transplacental transmission to a fetus, however, is possible in any phase. A diagnosis of late latent syphilis is justified only when the history and physical examination show no evidence of tertiary disease or neurosyphilis. The latent stage may last from months to a lifetime.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment of early latent syphilis and follow-up are the same as for primary syphilis unless CNS disease is present (Table 34–3). Treatment of late latent syphilis is also shown in Table 34–3. The treatment of this stage of the disease is intended to prevent late sequelae. If there is evidence of CNS involvement, a lumbar puncture should be performed and, if positive, the patient should receive treatment for neurosyphilis (see Spinal fluid examination for Neurosyphilis, below). Titers may not decline as rapidly following treatment compared to early syphilis. Nontreponemal serologic tests should be repeated at 6, 12, and 24 months. If titers increase fourfold or if initially high titers (1:32 or higher) fail to decrease fourfold by 12–24 months or if symptoms or signs consistent with syphilis develop, an HIV test should be repeated in HIV-uninfected patients, lumbar puncture should be performed, and re-treatment given according to the stage of the disease.

4. Tertiary (Late) Syphilis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Infiltrative tumors of skin, bones, liver (gummas).

Infiltrative tumors of skin, bones, liver (gummas).

Aortitis, aneurysms, aortic regurgitation.

Aortitis, aneurysms, aortic regurgitation.

CNS disorders: meningovascular and degenerative changes, paresthesias, shooting pains, abnormal reflexes, dementia, or psychosis.

CNS disorders: meningovascular and degenerative changes, paresthesias, shooting pains, abnormal reflexes, dementia, or psychosis.

General Considerations

General Considerations

This stage may occur at any time after secondary syphilis, even after years of latency, and is rarely seen in developed countries in the modern antibiotic era. Late lesions are thought to represent a delayed hypersensitivity reaction of the tissue to the organism and are usually divided into two types: (1) a localized gummatous reaction with a relatively rapid onset and generally prompt response to therapy and (2) diffuse inflammation of a more insidious onset that characteristically involves the CNS and large arteries, may not improve despite treatment, and is often fatal if untreated. Gummas may involve any area or organ of the body but most often affect the skin or long bones. Cardiovascular disease is usually manifested by aortic aneurysm, aortic regurgitation, or aortitis. Various forms of diffuse or localized CNS involvement may occur.

Late syphilis must be differentiated from neoplasms of the skin, liver, lung, stomach, or brain; other forms of meningitis; and primary neurologic lesions.

Although almost any tissue and organ may be involved in late syphilis, the following are the most common types of involvement: skin, mucous membranes, skeletal system, eyes, respiratory system, gastrointestinal system, cardiovascular system, and nervous system.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

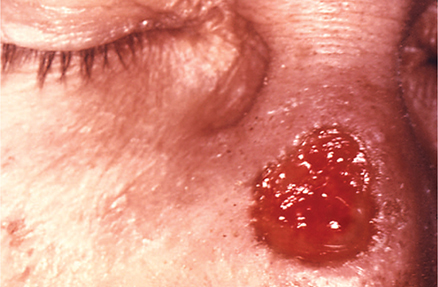

1. Skin—Cutaneous lesions of late syphilis are of two varieties: (1) multiple nodular lesions that eventually ulcerate (lues maligna) or resolve by forming atrophic, pigmented scars and (2) solitary gummas that start as painless subcutaneous nodules, then enlarge, attach to the overlying skin, and eventually ulcerate (Figure 34–5).

Figure 34–5. Gumma of the nose due to long-standing tertiary syphilis. (From J. Pledger, Public Health Image Library, CDC.)

2. Mucous membranes—Late lesions of the mucous membranes are nodular gummas or leukoplakia, highly destructive to the involved tissue.

3. Skeletal system—Bone lesions are destructive, causing periostitis, osteitis, and arthritis with little or no associated redness or swelling but often marked myalgia and myositis of the neighboring muscles.

4. Eyes—Late ocular lesions are gummatous iritis, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy, and cranial nerve palsies, in addition to the lesions of CNS syphilis.

5. Respiratory system—Respiratory involvement is caused by gummatous infiltrates into the larynx, trachea, and pulmonary parenchyma, producing discrete pulmonary densities. There may be hoarseness, respiratory distress, and wheezing secondary to the gummatous lesion itself or to subsequent stenosis occurring with healing.

6. Gastrointestinal system—Gummas involving the liver may be benign but can cause cirrhosis. Gastric involvement can consist of diffuse infiltration into the stomach wall or focal lesions that endoscopically and microscopically can be confused with lymphoma or carcinoma. Epigastric pain, early satiety, regurgitation, belching, and weight loss are common symptoms.

7. Cardiovascular system—Cardiovascular lesions (10–15% of tertiary syphilitic lesions) are often progressive, disabling, and life-threatening. CNS lesions are often present concomitantly. Involvement usually starts as an arteritis in the supracardiac portion of the aorta and progresses to one or more of the following: (1) narrowing of the coronary ostia, with resulting decreased coronary circulation, angina, and acute myocardial infarction; (2) scarring of the aortic valves, producing aortic regurgitation, and eventually heart failure; and (3) weakness of the wall of the aorta, with saccular aneurysm formation (Figure 34–6) and associated pressure symptoms of dysphagia, hoarseness, brassy cough, back pain (vertebral erosion), and occasionally rupture of the aneurysm. Recurrent respiratory infections are common as a result of pressure on the trachea and bronchi.

Figure 34–6. Ascending saccular aneurysm of the thoracic aorta in tertiary syphilis. (Public Health Image Library, CDC.)

8. Nervous system (neurosyphilis)—See next section.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment of tertiary syphilis (excluding neurosyphilis) is the same as late latent syphilis (Table 34–3); symptoms may not resolve after treatment. Positive serologic tests do not usually become negative.

The pretreatment clinical and laboratory evaluation should include neurologic, ocular, cardiovascular, psychiatric, and CSF examinations. In the presence of definite CSF or neurologic abnormalities, one should treat for neurosyphilis.

5. Neurosyphilis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Can occur at any stage of disease.

Can occur at any stage of disease.

Consider both clinical presentation and laboratory data.

Consider both clinical presentation and laboratory data.

Perform neurologic examination in all patients; consider CSF evaluation for atypical symptoms or lack of decrease in nontreponemal serology titers.

Perform neurologic examination in all patients; consider CSF evaluation for atypical symptoms or lack of decrease in nontreponemal serology titers.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Neurosyphilis can occur at any stage of disease and can be a progressive, disabling, and life-threatening complication. Asymptomatic CSF abnormalities and meningovascular syphilis occur earlier (months to years after infection, sometimes coexisting with primary and secondary syphilis) than tabes dorsalis and general paresis (2–50 years after infection).

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Classification

1. Asymptomatic neuroinvasion—This form has been reported in up to 40% of patients with early syphilis and is characterized by spinal fluid abnormalities (positive spinal fluid serology, lymphocytic pleocytosis, occasionally increased protein) without symptoms or signs of neurologic involvement. There are no clear data to support that these asymptomatic CSF abnormalities have clinical significance; therefore, unless treatment failure is suspected, routine CSF evaluation of asymptomatic patients is not recommended.

2. Meningovascular syphilis—This form is characterized by meningeal involvement or changes in the vascular structures of the brain (or both), producing symptoms of acute or chronic meningitis (headache, irritability); cranial nerve palsies (basilar meningitis); unequal reflexes; irregular pupils with poor light and accommodation reflexes; and when large vessels are involved, cerebrovascular accidents. The CSF shows lymphocytic pleocytosis (100–1000/mcL) and elevated protein, and may have a positive serologic test (CSF VDRL) for syphilis. The symptoms of acute meningitis are rare in late syphilis.

3. Tabes dorsalis—This is a chronic progressive degeneration of the parenchyma of the posterior columns of the spinal cord and of the posterior sensory ganglia and nerve roots. The symptoms and signs are impairment of proprioception and vibration sense, Argyll Robertson pupils (which react poorly to light but accommodate for near focus), and muscular hypotonia and hyporeflexia. Impaired proprioception results in a wide-based gait and inability to walk in the dark. Paresthesias, analgesia, or sharp recurrent pains in the muscles of the leg (“shooting” or “lightning” pains) may occur. Joint damage may occur as a result of lack of sensory innervation (Charcot joint, Figure 34–7). The CSF may have a normal or increased lymphocytic cell count, elevated protein, and variable results of serologic tests.

Figure 34–7. Neuropathic arthropathy (Charcot joint) from tertiary syphilis. (From Susan Lindsley, Public Health Image Library, CDC.)

4. General paresis—This is generalized involvement of the cerebral cortex with insidious onset of symptoms. There is usually a decrease in concentrating power, memory loss, dysarthria, tremor of the fingers and lips, irritability, and mild headaches. Most striking is the change of personality; the patient may become slovenly, irresponsible, confused, and psychotic. The CSF findings resemble those of tabes dorsalis. Combinations of the various forms of neurosyphilis (especially tabes and paresis) are not uncommon.

B. Laboratory Findings

See Serologic Tests for Syphilis, above; these tests should also be performed in cases of suspected neurosyphilis.

1. Indications for a lumbar puncture—In early syphilis (primary and secondary syphilis and early latent syphilis of less than 1 year’s duration), invasion of the CNS by T pallidum with CSF abnormalities occurs commonly, but clinical neurosyphilis rarely develops in patients who have received standard therapy. Thus, unless clinical symptoms or signs of neurosyphilis or ocular involvement (uveitis, neuroretinitis, optic neuritis, iritis) are present, a lumbar puncture is not routinely recommended. CSF evaluation is recommended, however, if neurologic or ophthalmologic symptoms or signs are present, if there is evidence of treatment failure (see earlier discussion), or if there is evidence of active tertiary syphilis (eg, aortitis, iritis, optic atrophy, the presence of a gumma).

2. Spinal fluid examination—CSF findings in neurosyphilis are variable. In “classic” cases, there is an elevation of total protein above 46 mg/dL, lymphocytic pleocytosis of 5–100 cells/mcL, and a positive CSF nontreponemal test. VDRL is more sensitive and preferred over RPR. The serum nontreponemal titers will be reactive in most cases. Because the CSF VDRL may be negative in 30–70% of cases of neurosyphilis, a negative test does not exclude neurosyphilis, while a positive test confirms the diagnosis. The CSF FTA-ABS is sometimes used; it is a highly sensitive test but lacks specificity, and a high serum titer of FTA-ABS may result in a positive CSF titer in the absence of neurosyphilis.

Treatment

Treatment

Neurosyphilis is treated with high doses of aqueous penicillin to achieve better penetration and higher drug levels in the CSF than is possible with benzathine penicillin G (Table 34–3). There are limited data for using ceftriaxone to treat neurosyphilis as well, but because other regimens have not been adequately studied, patients with a history of an IgE-mediated reaction to penicillin may require skin testing for allergy to penicillin and, if positive, should be desensitized. Because the 10- to 14-day treatment course for neurosyphilis is less than the 21 days recommended for treatment of late syphilis, CDC guidelines state that clinicians may consider giving an additional 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G intramuscularly once weekly for 1–3 weeks at the conclusion of the intravenous treatment.

All patients treated for neurosyphilis should have nontreponemal serologic tests done every 3–6 months. CDC guidelines recommend spinal fluid examinations at 6-month intervals until the CSF cell count is normal; however, there are data to suggest that normalization of serum titers is an acceptable surrogate for CSF response. If the serum nontreponemal titers do not normalize, consider repeating the CSF analysis; expert consultation may be helpful in this scenario. A second course of penicillin therapy may be given if the CSF cell count has not decreased at 6 months or is not normal at 2 years.

6. Syphilis in HIV-Infected Patients

Syphilis is common among HIV-infected individuals. Some data suggest that syphilis coinfection is associated with an increase in HIV viral load and a decrease in CD4 count that normalizes with therapy; other studies have not found an association with HIV disease progression. Overall, for optimal patient care as well as prevention of transmission to partners, guidelines for the primary care of HIV-infected patients recommend at least annual syphilis screening.

Interpretation of serologic tests should be the same for HIV-positive and HIV-negative persons. If the diagnosis of syphilis is suggested on clinical grounds but nontreponemal tests are negative, consider the prozone effect caused by very high antibody titers (see nontreponemal tests, above), or try direct examination of primary or secondary lesions for spirochetes.

HIV-positive patients with primary and secondary syphilis should have careful clinical and serologic follow-up at 3-month intervals. The use of antiretroviral therapy has been associated with reduced serologic failure rates after syphilis treatment.

The diagnosis of neurosyphilis in HIV-infected patients is complicated by the fact that mild CSF abnormalities may be found in HIV infection alone. Evaluate patients for visual and hearing changes, since ocular and auditory syphilis may not result in CSF abnormalities. Like in HIV-uninfected patients, routine lumbar puncture is not recommended in asymptomatic patients; it should be reserved for cases in which neurologic symptoms or signs are present or there is concern for treatment failure. Following treatment, CSF white blood cell counts should normalize within 12 months regardless of HIV status, while the CSF VDRL may take longer. As discussed above, the same criteria for failure apply to HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, and re-treatment regimens are the same.

For all stages and sites of syphilitic infection, treatment does not differ by HIV infection status. Most clinical experience in treating HIV-infected patients with syphilis is based on penicillin regimens; fewer data exist for treating the penicillin-allergic patient. Doxycycline or tetracycline regimens can be used for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis as well as for late latent syphilis and latent syphilis of unknown duration though with caution and close follow-up (Table 34–3). For neurosyphilis, limited efficacy data exist for ceftriaxone; close clinical and serologic follow-up after treatment is essential.

7. Syphilis in Pregnancy

All pregnant women should have a nontreponemal serologic test for syphilis at the time of the first prenatal visit (see Chapter 19). In women who may be at increased risk for syphilis or for populations in which there is a high prevalence of syphilis, additional nontreponemal tests should be performed during the third trimester at 28 weeks and again at delivery. The serologic status of all women who have delivered should be known before discharge from the hospital. Seropositive women should be considered infected and should be treated unless prior treatment with fall in antibody titer is medically documented.

The only recommended treatment for syphilis in pregnancy is penicillin in dosage schedules appropriate for the stage of disease (Table 34–3). Penicillin prevents congenital syphilis in 90% of cases, even when treatment is given late in pregnancy. Women with a history of penicillin allergy should be skin tested and desensitized if necessary. Tetracycline and doxycycline are contraindicated in pregnancy.

The infant should be evaluated immediately at birth, and, depending on the likelihood of infection, monitored for clinical and serologic manifestations in the first year of life.

Prevention of Syphilis

Prevention of Syphilis

A randomized controlled trial of doxycycline post exposure prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infection prevention among men who have sex with men enrolled in a larger HIV PrEP study in France resulted in a 73% reduction in syphilis and 70% in chlamydia. Further trials are underway to confirm these findings.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Consultation with the local public health department may help obtain all prior positive syphilis serologic results and may be helpful in complicated or atypical cases.

• Early (infectious) syphilis cases may be contacted for partner notification and treatment by local public health authorities.

When to Admit

When to Admit

• Pregnant women with syphilis and true penicillin allergy should be admitted for desensitization and treatment.

• Women in late pregnancy treated for early syphilis should have close outpatient monitoring or be admitted because the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction can induce premature labor.

• Patients with neurosyphilis usually require admission for treatment with aqueous penicillin.

Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet. 2017 Apr 15;389(10078):1550–7. [PMID: 27993382]

Ropper AH. Neurosyphilis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 3;381(14):1358–63. [PMID: 31577877]

Workowski KA et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Jun 5;64(RR-03):1–137. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Aug 28;64(33):924. [PMID: 26042815]

NON–SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED TREPONEMATOSES

A variety of treponemal diseases other than syphilis occur endemically in many tropical areas of the world. They are distinguished from disease caused by T pallidum by their nonsexual transmission via direct skin contact, their relatively high incidence in certain geographic areas and among children, and their tendency to produce less severe visceral manifestations. As in syphilis, skin, soft tissue, and bone lesions may develop, organisms can be demonstrated in infectious lesions with darkfield microscopy or immunofluorescence, but cannot be cultured in artificial media; the serologic tests for syphilis are positive; molecular methods such as PCR and genome sequencing are available, but not widely used in endemic areas; the diseases have primary, secondary, and sometimes tertiary stages. Treatment with 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G intramuscularly is generally curative in any stage of the non–sexually transmitted treponematoses. In cases of penicillin hypersensitivity, tetracycline, 500 mg orally four times a day for 10–14 days, is usually the recommended alternative. In randomized controlled trials, oral azithromycin (30 mg/kg once) was noninferior to benzathine penicillin G for the treatment of yaws in children.

YAWS

Yaws, the most prevalent of the endemic treponematoses, is largely limited to tropical regions and is caused by T pallidum subspecies pertenue. It is characterized by granulomatous lesions of the skin, mucous membranes, and bone. Yaws is rarely fatal, though if untreated it may lead to chronic disability and disfigurement. Yaws is acquired by direct nonsexual contact, usually in childhood, although it may occur at any age. The “mother yaw,” a painless papule that later ulcerates, appears 3–4 weeks after exposure. There is usually associated regional lymphadenopathy. Six to 12 weeks later, secondary lesions occur, which are raised papillomas and papules that weep highly infectious material appear and last for several months or years. Painful ulcerated lesions on the soles are called “crab yaws” because of the resulting gait. Late gummatous lesions may occur, with associated tissue destruction involving large areas of skin and subcutaneous tissues. The late effects of yaws, with bone change, shortening of digits, and contractions, may be confused with similar changes occurring in leprosy. CNS, cardiac, or other visceral involvement is rare. See above for therapy. The World Health Organization has set a goal of eliminating yaws using mass treatment with azithromycin; however, emergence of macrolide resistance has complicated this approach.

PINTA

Pinta is caused by T pallidum subspecies carateum. It occurs endemically in rural areas of Latin America, especially in Mexico, Colombia, and Cuba, and in some areas of the Pacific. A nonulcerative, erythematous primary papule spreads slowly into a papulosquamous plaque showing a variety of color changes (slate, lilac, black). Secondary lesions resemble the primary one and appear within a year after it. These appear successively, new lesions together with older ones; are most common on the extremities; and later show atrophy and depigmentation. Some cases show pigmentary changes and atrophic patches on the soles and palms, with or without hyperkeratosis, that are indistinguishable from “crab yaws.” See above for therapy.

ENDEMIC SYPHILIS (Bejel)

Endemic syphilis is an acute or chronic infection caused by T pallidum subspecies endemicum. It has been reported in a number of countries, particularly in the eastern Mediterranean area and in Southeast Asia. Moist ulcerated lesions of the skin or oral or nasopharyngeal mucosa are the most common manifestations. Generalized lymphadenopathy and secondary and tertiary bone and skin lesions are also common. Deep leg pain points to periostitis or osteomyelitis. In the late stages of disease, destructive gummatous lesions similar to those seen in yaws can develop, resulting in loss of cartilage and saber shin deformity. Cardiovascular and CNS involvement are rare. See above for therapy.

Marks M. Advances in the treatment of yaws. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018 Aug 29;3(3):E92. [PMID: 30274488]

Mitjà O. Re-emergence of yaws after single mass azithromycin treatment followed by targeted treatment: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2018 Apr 21;391(10130):1599–607. [PMID: 29428183]

SELECTED SPIROCHETAL DISEASES

RELAPSING FEVER

The infectious organisms in relapsing fever are spirochetes of the genus Borrelia. The infection has two forms: tick-borne and louse-borne. The main reservoir for tick-borne relapsing fever is rodents, which serve as the source of infection for ticks. Tick-borne relapsing fever may be transmitted transovarially from one generation of ticks to the next. Humans can be infected by tick bites or by rubbing crushed tick tissues or feces into the bite wound. Tick-borne relapsing fever is endemic, but is not transmitted from person to person. In the United States, infected ticks are found throughout the western states, but clinical cases are uncommon in humans.

The louse-borne form is primarily seen in the developing world, and humans are the only reservoir. Large epidemics may occur in louse-infested populations, and transmission is favored by crowding, malnutrition, and cold climate.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

There is an abrupt onset of fever, chills, tachycardia, nausea and vomiting, arthralgia, and severe headache. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly may develop, as well as various types of rashes (macular, papular, petechial) that usually occur at the end of a febrile episode. Delirium occurs with high fever, and there may be various neurologic and psychological abnormalities. The attack terminates, usually abruptly, after 3–10 days. After an interval of 1–2 weeks, relapse occurs, but often it is somewhat milder. Three to ten relapses may occur before recovery in tick-borne disease, whereas louse-borne disease is associated with only one or two relapses.

B. Laboratory Findings

During episodes of fever, large spirochetes are seen in thick and thin blood smears stained with Wright or Giemsa stain. The organisms can be cultured in special media but rapidly lose pathogenicity. The spirochetes can multiply in injected rats or mice and can be seen in their blood.

A variety of anti-Borrelia antibodies develop during the illness; sometimes the Weil–Felix test for rickettsioses and nontreponemal serologic tests for syphilis may also be falsely positive. Infection can cause false-positive indirect fluorescent antibody and Western blot tests for Borrelia burgdorferi, causing some cases to be misdiagnosed as Lyme disease. PCR assays can be performed on blood, CSF, and tissue but are not always available in endemic regions. CSF abnormalities occur in patients with meningeal involvement. Mild anemia and thrombocytopenia are common, but the white blood cell count tends to be normal.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The manifestations of relapsing fever may be confused with malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, yellow fever, typhus, or rat-bite fever.

Prevention

Prevention

Prevention of tick bites (as described for rickettsial diseases) and delousing procedures applicable to large groups can prevent illness. There are no vaccines for relapsing fever.

Postexposure prophylaxis with doxycycline 200 mg orally on day 1 and 100 mg daily for 4 days has been shown to prevent relapsing fever following tick bites in highly endemic areas.

Treatment

Treatment

A single dose of tetracycline or erythromycin, 0.5 g orally, or a single dose of procaine penicillin G, 600,000–800,000 units intramuscularly (adults), probably constitutes adequate treatment for louse-borne relapsing fevers; however, some experts advocate for longer courses of treatment to prevent persistent infection. In tick-borne disease, treatment begins with penicillin G, 3 million units intravenously every 4 hours, or ceftriaxone, 1 g intravenously daily; with clinical improvement, a 10-day course can be completed with 0.5 g of tetracycline or erythromycin given orally four times daily. If CNS invasion is suspected, intravenous penicillin G or ceftriaxone should be continued for 10–14 days. Jarisch–Herxheimer reactions occur commonly following treatment and may be life-threatening, so patients should be closely monitored (see Syphilis, above). All pregnant women with tick-borne disease should be treated for 14 days, ideally with intravenous penicillin or ceftriaxone.

Prognosis

Prognosis

The overall mortality rate is usually about 5%. Fatalities are most common in older, debilitated, or very young patients. With treatment, the initial attack is shortened and relapses are largely prevented.

Talagrand-Reboul E. Relapsing fevers: neglected tick-borne diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018 Apr 4;8:98. [PMID: 29670860]

RAT-BITE FEVER

Rat-bite fever is an uncommon acute infectious disease caused by the treponeme Spirillum minus (Asia) or the bacteria Streptobacillus moniliformis (North America). It is transmitted to humans by the bite of a rat. Inhabitants of rat-infested dwellings, owners of pet rats, and laboratory workers are at greatest risk.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

In Spirillum infections, the original rat bite, unless secondarily infected, heals promptly, but 1 to several weeks later the site becomes swollen, indurated, and painful. It assumes a dusky purplish hue and may ulcerate. Regional lymphangitis and lymphadenitis, fever, chills, malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, and headache are present. Splenomegaly may occur. A sparse, dusky-red maculopapular rash appears on the trunk and extremities in many cases, and there may be frank arthritis.

After a few days, both the local and systemic symptoms subside, only to reappear several days later. This relapsing pattern of fever for 3–4 days alternating with afebrile periods lasting 3–9 days may persist for weeks. The other features, however, usually recur only during the first few relapses. Endocarditis is a rare complication of infection.

B. Laboratory Findings

Leukocytosis is often present, and the nontreponemal test for syphilis is often falsely positive. The organism may be identified in darkfield examination of the ulcer exudate or aspirated lymph node material; more commonly, it is observed after inoculation of a laboratory animal with the patient’s exudate or blood. It has not been cultured in artificial media.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Rat-bite fever must be distinguished from the rat-bite–induced lymphadenitis and rash of streptobacillary fever. Clinically, the severe arthritis and myalgias seen in streptobacillary disease are rarely seen in disease caused by S minus. Reliable differentiation requires an increasing titer of agglutinins against S moniliformis or isolation of the causative organism. Other diseases in the differential include tularemia, rickettsial disease, Pasteurella multocida infections, and relapsing fever.

Treatment

Treatment

In acute illness, intravenous penicillin, 1–2 million units every 4–6 hours, is given initially; ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously daily is another option. Once improvement has occurred, therapy may be switched to oral penicillin V 500 mg four times daily, or amoxicillin 500 mg three times daily, to complete 10–14 days of therapy. For the penicillin-allergic patient, tetracycline 500 mg orally four times daily or doxycycline 100 mg twice a day can be used.

Prognosis

Prognosis

The reported mortality rate of about 10% should be markedly reduced by prompt diagnosis and antimicrobial treatment.

Walker JW et al. Rat bite fever: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Feb;35(2):e28–9. [PMID: 28002119]

LEPTOSPIROSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Clinical illness can vary from asymptomatic to fatal liver and kidney failure.

Clinical illness can vary from asymptomatic to fatal liver and kidney failure.

Anicteric leptospirosis: more common and milder form of the disease.

Anicteric leptospirosis: more common and milder form of the disease.

Icteric leptospirosis (Weil syndrome): impaired kidney and liver function, abnormal mental status, and hemorrhagic pneumonia; 5–40% mortality rate.

Icteric leptospirosis (Weil syndrome): impaired kidney and liver function, abnormal mental status, and hemorrhagic pneumonia; 5–40% mortality rate.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Leptospirosis is an acute and sometimes severe treponemal infection that is caused by 21 species within the genus Leptospira. The disease is distributed worldwide, and it is among the most common zoonotic infections. The leptospires enter through minor skin lesions and probably via the conjunctiva. Cases have occurred in international travelers after swimming or rafting in contaminated water, and occupational cases occur among sewer workers, rice planters, abattoir workers, and farmers. Sporadic urban cases have been seen in homeless persons exposed to rat urine.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Anicteric leptospirosis, the more common and milder form of the disease, is often biphasic. After an incubation period of 2–20 days, the initial or “septicemic” phase begins with abrupt fever to 39–40°C, chills, abdominal pain, severe headache, and myalgias, especially of the calf muscles. There may be marked conjunctival suffusion. Leptospires can be isolated from blood, CSF, and tissues. Following a 1- to 3-day period of improvement in symptoms and absence of fever, the second or “immune” phase begins; however, in severe disease the phases may appear indistinct. Leptospires are absent from blood and CSF but are still present in the kidney, and specific antibodies appear. A recurrence of symptoms is seen as in the first phase of disease with the onset of meningitis. Uveitis rash, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and adenopathy may occur. A rare but severe manifestation is hemorrhagic pneumonia. The illness is usually self-limited, lasting 4–30 days, and complete recovery is the rule.

Icteric leptospirosis (Weil syndrome) is the more severe form of the disease, characterized by impaired kidney and liver function, abnormal mental status, hemorrhagic pneumonia, hypotension, and a 5–40% mortality rate. Symptoms and signs often are continuous and not biphasic.

Leptospirosis with jaundice must be distinguished from hepatitis, yellow fever, rickettsial disease, and relapsing fever.

B. Laboratory Findings

The leukocyte count may be normal or as high as 50,000/mcL (0.05/L), with neutrophils predominating. The urine may contain bile, protein, casts, and red cells. Oliguria is common, and in severe cases uremia may occur. Elevated bilirubin and aminotransferases are seen in 75%, and elevated creatinine (greater than 1.5 mg/dL) (132.6 mcmol/L) is seen in 50% of cases. Serum creatine kinase is usually elevated in persons with leptospirosis and normal in persons with hepatitis. In cases with meningeal involvement, organisms may be found in the CSF during the first 10 days of illness. Early in the disease, the organism may be identified by darkfield examination of the patient’s blood (a test requiring expertise since false-positives are frequent in inexperienced hands) or by culture. Cultures take 1–6 weeks to become positive but may remain negative if antibiotics were started before culture was obtained. The organism may also be grown from the urine from the tenth day to the sixth week. Diagnosis is usually made by means of serologic tests, including the microscopic agglutination test (considered the gold standard but not widely available), and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). PCR molecular diagnostics are not widely available but appear to be sensitive, specific, positive early in disease, and able to detect leptospiral DNA in blood, urine, CSF, and aqueous humor.

Complications

Complications

Myocarditis, aseptic meningitis, acute kidney injury, and pulmonary infiltrates with hemorrhage are not common but are the usual causes of death. Iridocyclitis may occur.

Prevention

Prevention

The mainstay of prevention is avoidance of potentially contaminated food and water.

Prophylaxis with doxycycline (200 mg orally once a week) has been effective in trials and may be useful if a person is at high risk due to being in an area or season (eg, monsoon flooding) when exposure would be more likely. Human vaccine is used in some limited settings but is not widely available.

Treatment

Treatment

Many cases are self-limited without specific treatment. Various antimicrobial medications, including penicillin, ceftriaxone, and tetracyclines, show antileptospiral activity; however, meta-analysis has not demonstrated a clear survival benefit for any antibiotic. Doxycycline (100 mg every 12 hours orally or intravenously), penicillin (eg, 1.5 million units every 6 hours intravenously), and ceftriaxone (1 g daily intravenously) are used in severe leptospirosis. Jarisch–Herxheimer reactions may occur (see Syphilis, above). Although therapy for mild disease is controversial, most clinicians treat with doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily, for 7 days, or amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg, divided into three doses daily. Azithromycin is also active, but clinical experience is limited.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Without jaundice, the disease is almost never fatal. With jaundice, the mortality rate is 5% for those under age 30 years and 40% for those over age 60 years.

When to Admit

When to Admit

Patients with jaundice or other evidence of severe disease should be admitted for close monitoring and may require admission to an intensive care unit.

Bourque DL et al. Illnesses associated with freshwater recreation during international travel. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018 May 22;20(7):19. [PMID: 29789961]

Grennan D. JAMA patient page. Leptospirosis. JAMA. 2019 Feb 26;321(8):812. [PMID: 30806697]

Jiménez JIS et al. Leptospirosis: report from the task force on tropical diseases by the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. J Crit Care. 2018 Feb;43:361–5. [PMID: 29129539]

LYME DISEASE (Lyme Borreliosis)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Erythema migrans: a flat or slightly raised red lesion that expands with central clearing.

Erythema migrans: a flat or slightly raised red lesion that expands with central clearing.

Headache or stiff neck.

Headache or stiff neck.

Arthralgias, arthritis, and myalgias; arthritis is often chronic and recurrent.

Arthralgias, arthritis, and myalgias; arthritis is often chronic and recurrent.

General Considerations

General Considerations

This illness, named after the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, is the most common tick-borne disease in the United States and Europe and is caused by genospecies of the spirochete B burgdorferi. Most US cases are reported from the mid-Atlantic, northeastern, and north central regions of the country. The true incidence of Lyme disease is not known for a number of reasons: (1) serologic tests are not standardized (see below); (2) clinical manifestations are nonspecific; and (3) even with reliable testing, serology is insensitive in early disease.

The tick vector of Lyme disease varies geographically and is Ixodes scapularis in the northeastern, north central, and mid-Atlantic regions of the United States; Ixodes pacificus on the West Coast; Ixodes ricinus in Europe; and Ixodes persulcatus in Asia. The disease also occurs in Australia. Mice and deer make up the major animal reservoir of B burgdorferi, but other rodents and birds may also be infected. Domestic animals such as dogs, cattle, and horses can also develop clinical illness, usually manifested as arthritis.

Under experimental conditions, ticks must feed for 24–36 hours or longer to transmit infections. Most cases are reported in the spring and summer months. In addition, the percentage of ticks infected varies on a regional basis. In the northeastern and midwestern United States, 15–65% of I scapularis ticks are infected with the spirochete; in the west, less than 5% of I pacificus are infected. These are important epidemiologic features in assessing the likelihood that tick exposure will result in disease. Eliciting a history of brushing a tick off the skin (ie, the tick was not feeding) or removing a tick on the same day as exposure (ie, the tick did not feed long enough) decreases the likelihood that infection will develop.

Because the Ixodes tick is so small, the bite is usually painless and goes unnoticed. After feeding, the tick drops off in 2–4 days. If a tick is found, it should be removed immediately. The best way to accomplish this is to use fine-tipped tweezers to pull firmly and repeatedly on the tick’s mouth part—not the tick’s body—until the tick releases its hold. Saving the tick in a bottle of alcohol for future identification may be useful, especially if symptoms develop.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The three stages of Lyme disease are classified based on early or late manifestations of the disease and whether it is localized or disseminated.

A. Symptoms and Signs

1. Stage 1, early localized infection—Stage 1 infection is characterized by erythema migrans (Figure 6–26). About 1 week after the tick bite (range, 3–30 days; median 7–10 days), a flat or slightly raised red lesion appears at the site, which is commonly seen in areas of tight clothing such as the groin, thigh, or axilla. This lesion expands over several days. Although originally described as a lesion that progresses with central clearing (“bulls-eye” lesion), often there is a more homogeneous appearance or even central intensification. About 10–20% of patients either do not have typical skin lesions or the lesions go unnoticed. Most patients with erythema migrans will have a concomitant viral-like illness (the “summer flu”) characterized by myalgias, arthralgias, headache, and fatigue. Fever may or may not be present. Even without treatment, the symptoms and signs of erythema migrans resolve in 3–4 weeks. Although the classic lesion of erythema migrans is not difficult to recognize, atypical forms can occur that may lead to misdiagnosis. Southern tick–associated rash illness (STARI) has a similar appearance, but it occurs in geographically distinct areas of the United States.

Completely asymptomatic disease, without erythema migrans or flu-like symptoms, can occur but is very uncommon in the United States.

2. Stage 2, early disseminated infection—Up to 50–60% of patients with erythema migrans are bacteremic and within days to weeks of the original infection, secondary skin lesions develop in about 50% of patients. These lesions are similar in appearance to the primary lesion but are usually smaller. Malaise, fatigue, fever, headache (sometimes severe), neck pain, and generalized achiness are common with the skin lesions. Most symptoms are transient. After hematogenous spread, some patients experience cardiac (4–10% of patients) or neurologic (10–15% of patients) manifestations, including myopericarditis, with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and heart block. Neurologic manifestations include both the central and peripheral nervous systems. The most common CNS manifestation is aseptic meningitis with mild headache and neck stiffness. The most common peripheral manifestation is a cranial nerve VII neuropathy, ie, facial palsy (usually unilateral but can be bilateral, see Figure 24–1). A sensory or motor radiculopathy and mononeuritis multiplex occur less frequently. Conjunctivitis, keratitis, and, rarely, panophthalmitis can also occur. Rarely, skin involvement can be manifested as a cutaneous hypopigmented lesion called a borrelial lymphocytoma.

3. Stage 3, late persistent infection—Stage 3 infection occurs months to years after the initial infection and again primarily manifests itself as musculoskeletal, neurologic, and skin disease. In early reports, musculoskeletal complaints developed in up to 60% of patients, but with early recognition and treatment of disease, this has decreased to less than 10%. The classic manifestation of late disease is a monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritis most commonly affecting the knee or other large weight bearing joints. While these joints may be quite swollen, these patients generally report less pain compared to patients with bacterial septic arthritis. Even if untreated, the arthritis is self-limited, resolving in a few weeks to months. Multiple recurrences are common but are usually less severe than the original disease. Joint fluid reflects an inflammatory arthritis with a mean white blood cell count of 25,000/mcL (0.025/L) with a predominance of neutrophils. Chronic arthritis develops in about 10% of patients. The pathogenesis of chronic Lyme arthritis may be an immunologic phenomenon rather than persistence of infection.

Rarely, the nervous system (both central and peripheral) can be involved in late Lyme disease. In the United States, a subacute encephalopathy, characterized by memory loss, mood changes, and sleep disturbance, is seen. In Europe, a more severe encephalomyelitis caused by B garinii is seen and presents with cognitive dysfunction, spastic paraparesis, ataxia, and bladder dysfunction. Peripheral nervous system involvement includes intermittent paresthesias, often in a stocking glove distribution, or radicular pain.

The cutaneous manifestation of late infection, which can occur up to 10 years after infection, is acrodermatitis chronicum atrophicans. It has been described mainly in Europe after infection with B afzelii. There is usually bluish-red discoloration of a distal extremity with associated swelling. These lesions become atrophic and sclerotic with time and eventually resemble localized scleroderma. Cases of diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia, an entity that resembles scleroderma, have been rarely associated with infection with B burgdorferi.

B. Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is based on both clinical manifestations and laboratory findings. The US Surveillance Case Definition specifies a person with exposure to a potential tick habitat (within the 30 days just prior to developing erythema migrans) with (1) erythema migrans diagnosed by a clinician or (2) at least one late manifestation of the disease and (3) laboratory confirmation as fulfilling the criteria for Lyme disease.

Nonspecific laboratory abnormalities can be seen, particularly in early disease. The most common are an elevated sedimentation rate of more than 20 mm/h seen in 50% of cases, and mildly abnormal liver biochemical tests are present in 30%. The abnormal liver biochemical tests are transient and return to normal within a few weeks of treatment. A mild anemia, leukocytosis (11,000–18,000/mcL) (0.011–0.018/L), and microscopic hematuria have been reported in 10% or less of patients.

Laboratory confirmation requires serologic tests to detect specific antibodies to B burgdorferi in serum, preferably by ELISA and not by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), which is less sensitive and specific and can cause misdiagnosis. A two-test approach is recommended for the diagnosis of active Lyme disease, with all specimens positive or equivocal by ELISA then confirmed with a Western immunoblot assay that can detect both IgM and IgG antibodies. A positive immunoblot requires that antibodies are detected against two (for IgM) or five (for IgG) specific protein antigens from B burgdorferi.

If a patient with suspected early Lyme disease has negative serologic studies, acute and convalescent titers should be obtained since up to 50% of patients with early disease can be antibody negative in the first several weeks of illness. A fourfold rise in antibody titer would be diagnostic of recent infection. In patients with later stages of disease, almost all are antibody positive. False-positive reactions in the ELISA and IFA have been reported in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, infectious mononucleosis, subacute infective endocarditis, syphilis, relapsing fever, leptospirosis, enteroviral and other viral illnesses, and patients with gingival disease. False-negative serologic reactions occur early in illness, and antibiotic therapy early in disease can abort subsequent seroconversion.

The diagnosis of late nervous system Lyme disease is often difficult since clinical manifestations, such as subtle memory impairment, may be difficult to document. Most patients have a history of previous erythema migrans or monoarticular or polyarticular arthritis, and the vast majority have antibody present in serum. Patients with late disease and peripheral neuropathy almost always have positive serum antibody tests, usually have abnormal electrophysiology tests, and may have abnormal nerve biopsies showing perivascular collections of lymphocytes; however, the CSF is usually normal and does not demonstrate local antibody production.

Caution should be exercised in interpreting serologic tests because they are not subject to national standards, and inter-laboratory variation is a major problem. In addition, some laboratories perform tests that are entirely unreliable and should never be used to support the diagnosis of Lyme disease (eg, the Lyme urinary antigen test, immunofluorescent staining for cell wall–deficient forms of B burgdorferi, lymphocyte transformation tests, using PCR on inappropriate specimens such as blood or urine). Finally, testing is often done in patients with nonspecific symptoms such as headache, arthralgia, myalgia, fatigue, and palpitations. Even in endemic areas, the pretest probability of having Lyme disease is low in these patients, and the probability of a false-positive test result is greater than that of a true-positive result. For these reasons, the CDC has established guidelines for laboratory evaluation of patients with suspected Lyme disease:

1. The diagnosis of early Lyme disease is clinical (ie, exposure in an endemic area, with clinician-documented erythema migrans), and does not require laboratory confirmation. (Tests are often negative at this stage.)

2. Late disease requires objective evidence of clinical manifestations (recurrent brief attacks of monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritis of the large joints; lymphocytic meningitis, cranial neuritis [facial palsy], peripheral neuropathy or, rarely, encephalomyelitis—but not headache, fatigue, paresthesias, or stiff neck alone; atrioventricular conduction defects with or without myocarditis) and laboratory evidence of disease (two-stage testing with ELISA or IFA followed by Western blot, as described above).

3. Patients with nonspecific symptoms without objective signs of Lyme disease should not have serologic testing done. It is in this setting that false-positive tests occur more commonly than true-positive tests.

4. The role of serologic testing in nervous system Lyme disease is unclear, as sensitivity and specificity of CSF serologic tests have not been determined. However, it is rare for a patient to have positive serologic tests on CSF without positive tests on serum (see below).

5. Other tests such as the T cell proliferative assay and urinary antigen detection have not yet been studied well enough to be routinely used.

Cultures for B burgdorferi can be performed but are not routine and are usually reserved for clinical studies.

PCR is very specific for detecting the presence of Borrelia DNA, but sensitivity is variable and depends on which body fluid is tested, the stage of the disease, and collection and testing technique. In general, PCR is more sensitive than culture, especially in chronic disease but is not available in many clinical laboratories. Testing should not be done on blood or urine but has been successfully performed on synovial fluid and CSF. A negative PCR result does not rule out disease.

Complications

Complications

Based on several observational studies, B burgdorferi infection in pregnant women has not been associated with congenital syndromes, unlike other spirochetal illnesses such as syphilis.

Some patients and advocacy groups have claimed either a post–Lyme syndrome (in the presence of positive laboratory tests and after appropriate treatment) or “chronic Lyme disease” in which tests may all be negative. Both entities include nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, myalgias, and cognitive difficulties (see Prognosis below). Expert groups are in agreement that there are no data to support that ongoing infection is the cause of either syndrome.

Prevention

Prevention

There is no human vaccine currently available. Simple preventive measures such as avoiding tick-infested areas, covering exposed skin with long-sleeved shirts and wearing long trousers tucked into socks, wearing light-colored clothing, using repellents, and inspecting for ticks after exposure will greatly reduce the number of tick bites. Environmental controls directed at limiting ticks on residential property would be helpful, but trying to limit the deer, tick, or white-footed mouse populations over large areas is not feasible.

Prophylactic antibiotics following tick bites is recommended in certain high-risk situations if all of the following criteria are met: (1) a tick identified as an adult or nymphal I scapularis has been attached for at least 36 hours; (2) prophylaxis can be started within 72 hours of the time the tick was removed; (3) more than 20% of ticks in the area are known to be infected with B burgdorferi; and (4) there is no contraindication to the use of doxycycline (not pregnant, age greater than 8 years, not allergic). The medication of choice for prophylaxis is a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline. If doxycycline is contraindicated, no prophylaxis should be given and the patient should be closely monitored for early disease, since short course prophylactic therapy with other agents has not been studied, and if early disease does develop, appropriate therapy is very effective in preventing long-term sequelae. Individuals who have removed ticks (including those who have had prophylaxis) should be monitored carefully for 30 days for possible coinfections.

Coinfections

Coinfections

Lyme disease, babesiosis (see Chapter 35), and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (formerly human granulocytic ehrlichiosis) (see Chapter 32) are endemic in similar areas of the country and are transmitted by the same tick, I scapularis. Coinfection with two or even all three of these organisms can occur, causing a clinical picture that is not “classic” for any of these diseases. The presence of erythema migrans is highly suggestive of Lyme disease, whereas flu-like symptoms without rash are more suggestive of babesiosis or anaplasmosis. Coinfection should be considered and excluded in patients who have persistent high fevers 48 hours after starting appropriate therapy for Lyme disease; in patients with persistent symptoms despite resolution of rash; and in those with anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.

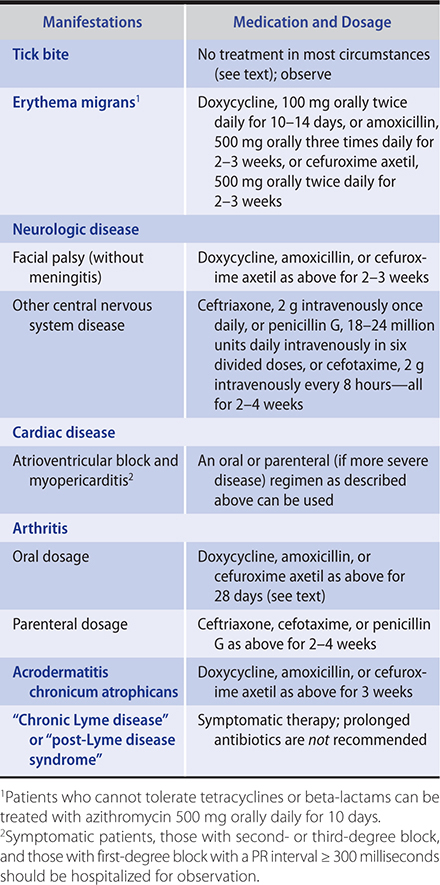

Treatment

Treatment